Difference between revisions of "Ethylene" - New World Encyclopedia

(→External links: Checked links and added Retrieved dates.) |

|||

| Line 109: | Line 109: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

| − | '''Ethylene''' (or [[IUPAC]] name '''ethene''') is | + | |

| + | '''Ethylene''' (or [[IUPAC]] name '''ethene''') is a [[chemical compound]] with the formula C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>4</sub>. Each molecule contains a double bond between the two carbon atoms, and for this reason it is classified as an '''[[alkene]]''', '''olefin''', or '''unsaturated hydrocarbon'''. At ordinary temperatures and pressures, it is a [[gas]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In biological systems, ethylene acts as a [[hormone]].<ref name=Wang_2002>Wang K., H. Li, J. Ecker. Ethylene biosynthesis and signaling networks. ''Plant Cell''. 14 Suppl:S131-51.</ref> It is also extremely important in industry and is the most produced [[organic compound]] in the world. Global production of ethylene exceeded 75 million metric tons per year in 2005.<ref>2006. Production: Growth is the Norm. ''Chemical and Engineering News''. p. 59.</ref> | ||

== History== | == History== | ||

| Line 115: | Line 118: | ||

From 1795 on, ethylene was referred to as the ''olefiant gas'' (oil-making gas), because it combined with [[chlorine]] to produce the "oil of the Dutch chemists" ([[1,2-Dichloroethane|1,2-dichloroethane]]), first synthesized in 1795 by a collaboration of four [[Netherlands|Dutch]] chemists. | From 1795 on, ethylene was referred to as the ''olefiant gas'' (oil-making gas), because it combined with [[chlorine]] to produce the "oil of the Dutch chemists" ([[1,2-Dichloroethane|1,2-dichloroethane]]), first synthesized in 1795 by a collaboration of four [[Netherlands|Dutch]] chemists. | ||

| − | In the mid-nineteenth century, the suffix ''-ene'' (an Ancient Greek root added to the end of female names meaning "daughter of") was widely used to refer to a molecule or part thereof that contained one fewer hydrogen atoms than the molecule being modified. | + | In the mid-nineteenth century, the suffix ''-ene'' (an Ancient Greek root added to the end of female names meaning "daughter of") was widely used to refer to a molecule or part thereof that contained one fewer hydrogen atoms than the molecule (or molecular component) being modified. Thus, ''ethylene'' (C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>4</sub>) was thought of as the "daughter of [[ethyl]]" (C<sub>2</sub>H<sub>5</sub>). The name ethylene was used in this sense as early as 1852. |

| − | In 1866, the [[Germany|German]] chemist [[August Wilhelm von Hofmann]] proposed a system of hydrocarbon nomenclature in which the suffixes -ane, -ene, -ine, -one, and -une were used to denote | + | In 1866, the [[Germany|German]] chemist [[August Wilhelm von Hofmann]] proposed a system of hydrocarbon nomenclature in which the suffixes -ane, -ene, -ine, -one, and -une were used to denote hydrocarbons with 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 fewer hydrogen atoms (per molecule) than their parent [[alkane]].<ref>Hofmann, A.W. 1866. [http://www.chem.yale.edu/~chem125/125/history99/5Valence/Nomenclature/Hofmannaeiou.html Hofmann's Proposal for Systematic Nomenclature of the Hydrocarbons : "On the Action of Trichloride of Phosphorus on the Salts of the Aromatic Monamines"]. Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> In this system, ethylene became ''ethene''. Hofmann's system eventually became the basis for the Geneva nomenclature approved by the International Congress of Chemists in 1892, which remains at the core of the [[IUPAC]] nomenclature. By then, however, the name ethylene was deeply entrenched, and it remains in wide use today, especially in the chemical industry. |

| − | The 1979 IUPAC nomenclature rules | + | The 1979 IUPAC nomenclature rules made an exception for retaining the non-systematic name ethylene,<ref>[http://www.acdlabs.com/iupac/nomenclature/79/r79_53.htm#a_3__1 IUPAC nomenclature rule A-3.1 (1979)]. Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> but this decision was reversed in the 1993 rules.<ref>[http://www.acdlabs.com/iupac/nomenclature/93/r93_684.htm Footnote to IUPAC nomenclature rule R-9.1, table 19(b)]. Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> |

==Structure== | ==Structure== | ||

| − | + | As mentioned above, each molecule of ethylene contains a pair of [[carbon]] atoms that are connected to each other by a [[double bond]]. In addition, two [[hydrogen]] [[atom]]s are bound to each carbon atom. All six atoms in an ethylene molecule are [[coplanar]]. The H-C-H [[angle]] is 117°, close to the 120° for ideal sp<sup>2</sup> [[hybridization (chemistry)|hybridized]] carbon. The molecule is also relatively rigid: rotation about the C-C bond is a high energy process that requires breaking the π-bond, while retaining the σ-bond between the carbon atoms. | |

The double bond is a region of high [[electron density]], and most reactions occur at this double bond position. | The double bond is a region of high [[electron density]], and most reactions occur at this double bond position. | ||

| − | == | + | === Interpretation of its spectrum === |

| − | + | Although ethylene is a relatively simple molecule, its [[Spectroscopy|spectrum]]<ref name=NIST_Webbook>[http://webbook.nist.gov/cgi/cbook.cgi?ID=C74851&Units=SI&Mask=400#UV-Vis-Spec Ethylene:UV/Visible Spectrum]. NIST Webbook. Retrieved September 12, 2007.</ref> is considered one of the most difficult to explain adequately from both a theoretical and practical perspective. For this reason, it is often used as a test case in [[computational chemistry]]. Of particular note is the difficulty in characterizing the ultraviolet absorption of the molecule. Interest in the subtleties and details of the ethylene spectrum can be dated back to at least the 1950s. | |

| − | + | == Production == | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In the [[petrochemical]] industry, ethylene is produced by a process known as ''[[steam cracking]]''. In this process, gaseous or light liquid hydrocarbons are briefly heated to 750–950 °C, inducing numerous [[free radical]] [[chemical reaction|reactions]]. This process converts large hydrocarbons into smaller ones and introduces unsaturation. Ethylene is separated from the resulting complex mixture by repeated [[Physical compression|compression]] and [[distillation]]. In a related process used in oil refineries, high molecular weight hydrocarbons are cracked over [[Zeolite]] catalysts. | |

| − | + | Heavier feedstocks, such as naphtha and gas oils, require at least two "quench towers" downstream of the cracking furnaces to recirculate pyrolysis-derived gasoline and process water. When cracking a mixture of ethane and propane, only one water quench tower is required.<ref name=Keystone>Kniel, Ludwig. 1980. ''Ethylene Keystone to the Petrochemical Industry''. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-6914-7</ref> | |

| − | + | Given that the production of ethylene is energy intensive, much effort has been dedicated to recover heat from the gas leaving the furnaces. Most of the energy recovered from the cracked gas is used to make high pressure (1200 psig) steam. This steam is in turn used to drive the turbines for compressing cracked gas, the propylene refrigeration compressor, and the ethylene refrigeration compressor. An ethylene plant, once running, does not need to import any steam to drive its steam turbines. A typical world scale ethylene plant (about 1.5 billion pounds of ethylene per year) uses a 45,000 horsepower cracked gas compressor, a 30,000 horsepower propylene compressor, and a 15,000 horsepower ethylene compressor. | |

| − | |||

==Chemical reactions== | ==Chemical reactions== | ||

| − | Ethylene is an extremely important building block in the petrochemical industry. It can undergo many types of reactions | + | Ethylene is an extremely important building block in the petrochemical industry. It can undergo many types of reactions that generate a plethora of chemical products. Some of its major reactions includes: 1) [[Polymerization]], 2) [[Oxidation]], 3) [[Halogenation]] and [[Hydrohalogenation]], 4) [[Alkylation]], 5) [[Hydration]], 6) [[Oligomerization]], 7) [[Hydroformylation|Oxo-reaction]], and 8) a ripening agent for fruits and vegetables (see [[#Physiological responses of plants|Physiological responses of plants]]).<ref name=Keystone/> |

===Additions to double bond=== | ===Additions to double bond=== | ||

Revision as of 18:49, 21 September 2007

| Ethylene | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Systematic name | Ethene |

| Molecular formula | C2H4 |

| SMILES | C=C |

| Molar mass | 28.05 g/mol |

| Appearance | colourless gas |

| CAS number | [74-85-1] |

| Properties | |

| Density and phase | 1.178 g/l at 15 °C, gas |

| Solubility of gas in water | 25 mL/100 mL (0 °C) 12 mL/100 mL (25 °C)[1] |

| Melting point | −169.1 °C |

| Boiling point | −103.7 °C |

| Structure | |

| Molecular shape | planar |

| Dipole moment | zero |

| Symmetry group | D2h |

| Thermodynamic data | |

| Std enthalpy of formation ΔfH°gas |

+52.47 kJ/mol |

| Standard molar entropy S°gas |

219.32 J·K−1·mol−1 |

| Hazards | |

| MSDS | External MSDS |

| EU classification | Extremely flammable (F+) |

| NFPA 704 | |

| R-phrases | R12, R67 |

| S-phrases | S2, S9, S16, S33, S46 |

| Flash point | Flammable gas |

| Explosive limits | 2.7–36.0% |

| Autoignition temperature | 490 °C |

| Supplementary data page | |

| Structure and properties |

n, εr, etc. |

| Thermodynamic data |

Phase behaviour Solid, liquid, gas |

| Spectral data | UV, IR, NMR, MS |

| Related compounds | |

| Other alkenes | Propene Butene |

| Related compounds | Ethane Acetylene |

| Except where noted otherwise, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C, 100 kPa) Infobox disclaimer and references | |

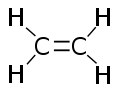

Ethylene (or IUPAC name ethene) is a chemical compound with the formula C2H4. Each molecule contains a double bond between the two carbon atoms, and for this reason it is classified as an alkene, olefin, or unsaturated hydrocarbon. At ordinary temperatures and pressures, it is a gas.

In biological systems, ethylene acts as a hormone.[2] It is also extremely important in industry and is the most produced organic compound in the world. Global production of ethylene exceeded 75 million metric tons per year in 2005.[3]

History

From 1795 on, ethylene was referred to as the olefiant gas (oil-making gas), because it combined with chlorine to produce the "oil of the Dutch chemists" (1,2-dichloroethane), first synthesized in 1795 by a collaboration of four Dutch chemists.

In the mid-nineteenth century, the suffix -ene (an Ancient Greek root added to the end of female names meaning "daughter of") was widely used to refer to a molecule or part thereof that contained one fewer hydrogen atoms than the molecule (or molecular component) being modified. Thus, ethylene (C2H4) was thought of as the "daughter of ethyl" (C2H5). The name ethylene was used in this sense as early as 1852.

In 1866, the German chemist August Wilhelm von Hofmann proposed a system of hydrocarbon nomenclature in which the suffixes -ane, -ene, -ine, -one, and -une were used to denote hydrocarbons with 0, 2, 4, 6, and 8 fewer hydrogen atoms (per molecule) than their parent alkane.[4] In this system, ethylene became ethene. Hofmann's system eventually became the basis for the Geneva nomenclature approved by the International Congress of Chemists in 1892, which remains at the core of the IUPAC nomenclature. By then, however, the name ethylene was deeply entrenched, and it remains in wide use today, especially in the chemical industry.

The 1979 IUPAC nomenclature rules made an exception for retaining the non-systematic name ethylene,[5] but this decision was reversed in the 1993 rules.[6]

Structure

As mentioned above, each molecule of ethylene contains a pair of carbon atoms that are connected to each other by a double bond. In addition, two hydrogen atoms are bound to each carbon atom. All six atoms in an ethylene molecule are coplanar. The H-C-H angle is 117°, close to the 120° for ideal sp2 hybridized carbon. The molecule is also relatively rigid: rotation about the C-C bond is a high energy process that requires breaking the π-bond, while retaining the σ-bond between the carbon atoms.

The double bond is a region of high electron density, and most reactions occur at this double bond position.

Interpretation of its spectrum

Although ethylene is a relatively simple molecule, its spectrum[7] is considered one of the most difficult to explain adequately from both a theoretical and practical perspective. For this reason, it is often used as a test case in computational chemistry. Of particular note is the difficulty in characterizing the ultraviolet absorption of the molecule. Interest in the subtleties and details of the ethylene spectrum can be dated back to at least the 1950s.

Production

In the petrochemical industry, ethylene is produced by a process known as steam cracking. In this process, gaseous or light liquid hydrocarbons are briefly heated to 750–950 °C, inducing numerous free radical reactions. This process converts large hydrocarbons into smaller ones and introduces unsaturation. Ethylene is separated from the resulting complex mixture by repeated compression and distillation. In a related process used in oil refineries, high molecular weight hydrocarbons are cracked over Zeolite catalysts.

Heavier feedstocks, such as naphtha and gas oils, require at least two "quench towers" downstream of the cracking furnaces to recirculate pyrolysis-derived gasoline and process water. When cracking a mixture of ethane and propane, only one water quench tower is required.[8]

Given that the production of ethylene is energy intensive, much effort has been dedicated to recover heat from the gas leaving the furnaces. Most of the energy recovered from the cracked gas is used to make high pressure (1200 psig) steam. This steam is in turn used to drive the turbines for compressing cracked gas, the propylene refrigeration compressor, and the ethylene refrigeration compressor. An ethylene plant, once running, does not need to import any steam to drive its steam turbines. A typical world scale ethylene plant (about 1.5 billion pounds of ethylene per year) uses a 45,000 horsepower cracked gas compressor, a 30,000 horsepower propylene compressor, and a 15,000 horsepower ethylene compressor.

Chemical reactions

Ethylene is an extremely important building block in the petrochemical industry. It can undergo many types of reactions that generate a plethora of chemical products. Some of its major reactions includes: 1) Polymerization, 2) Oxidation, 3) Halogenation and Hydrohalogenation, 4) Alkylation, 5) Hydration, 6) Oligomerization, 7) Oxo-reaction, and 8) a ripening agent for fruits and vegetables (see Physiological responses of plants).[8]

Additions to double bond

Like most alkenes, ethylene reacts with halogens to produce halogenated hydrocarbons1,2-C2H4X2. It can also react with water to produce ethanol, but the rate at which this happens is very slow unless a suitable catalyst, such as phosphoric or sulfuric acid, is used. Under high pressure, and, in the presence of a catalytic metal (platinum, rhodium, nickel), hydrogen will react with ethylene to form ethane.

Ethylene is used primarily as an intermediate in the manufacture of other chemicals in the synthesis of monomers. Ethylene can be chlorinated to produce 1,2-dichloroethane (ethylene dichloride). This can be converted to vinyl chloride, the monomer precursor to plastic polyvinyl chloride, or combined with benzene to produce ethylbenzene, which is used in the manufacture of polystyrene, another important plastic.

Ethylene is more reactive than alkanes for two reasons:

1. It has a double bond, one called the π-bond(pi) and one called the σ-bond (sigma). Where π-bond is weak and σ-bond is strong. The presence of the π-bond makes it a high energy molecule. Thus bromine water decolorises readily when it is added to ethylene.

2. High electron density at the double bond makes it react readily. It is broken in an addition reaction to produce many useful products.

Polymerization

Ethylene polymerizes to produce polyethylene, also called polyethene or polythene, the world's most widely-used plastic.

Major polyethylene product groups are low density polyethylene, high density polyethylene, polyethylene copolymers, as well as ethylene-propylene co- & terpolymers.[8]

Oxidation

Ethylene is oxidized to produce ethylene oxide, which is hydrolysed to ethylene glycol. It is also a precursor to vinyl acetate.

Ethylene undergoes oxidation by palladium to give acetaldehyde. This conversion was at one time a major industrial process.[9] The process proceeds via the initial complexation of ethylene to a Pd(II) center.

Major intermediates of the oxidation of Ethylene are ethylene oxide, acetaldehyde, vinyl acetate and ethylene glycol. The list of products made from these intermediates is long. Some of them are: polyesters, polyurethane, morpholine, ethanolamines, aspirin and glycol ethers.[8]

Halogenation and Hydrohalogenation

Major intermediates from the halogenation and hydrohalogenation of ethylene include: ethylene dichloride, ethyl chloride and ethylene dibromide. Some products in this group are: polyvinyl chloride, trichloroethylene, perchloroethylene, methyl chloroform, polyvinylidiene chloride and copolymers, and ethyl bromide.[8]

Alkylation

Major chemical intermediates from the alkylation of ethylene include: ethylbenzene, ethyl toluene, ethyl anilines, 1,4-hexadiene and aluminum alkyls. Products of these intermediates include polystyrene, unsaturated polyesters and ethylene-propylene terpolymers.[8]

Hydration

Ethanol is the primary intermediate of the hydration of ethylene. Important products from ethanol are: ethylamines, yeast, acetaldehyde, and ethyl acetate.[8]

Oligomerization

The primary products of the Oligomerization of ethylene are alpha-olefins and linear primary alcohols. These are used as plasticizers and surfactants.[8]

Oxo-reaction

The Oxo-reaction of ethylene results in propionaldehyde with its' primary products of propionic acid and n-propyl alcohol.[8]

In the synthesis of fine chemicals

Ethylene is useful in organic synthesis.[10] Representative reactions include Diels-Alder additions, ene reaction, and arene alkylation.

Miscellaneous

Ethylene was once used as a general anesthetic applicable via inhalation, but it has long since been replaced (see Effects Upon Humans, below).

It has also been hypothesized that ethylene was the catalyst for utterances of the oracle at Delphi in ancient Greece.[11]

It is also found in many lip gloss products.

Production of Ethylene in mineral oil filled transformers is a key indicator of severe localized overheating (>750 degrees C.)[12]

Ethylene as a plant hormone

Template:Cleanup-section Ethylene acts physiologically as a hormone in plants.[13][14] It exists as a gas and acts at trace levels throughout the life of the plant by stimulating or regulating the ripening of fruit, the opening of flowers, and the abscission (or shedding) of leaves. Its biosynthesis starts from methionine with 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) as a key intermediate.

It has been shown that ethylene is produced from essentially all parts of higher plants, including leaves, stems, roots, flowers, fruits, tubers, and seedlings. The ethylene produced by the fruit is especially harmful to plants to other fruits and vegetables. The fruit that is the main producer of ethylene gas is apples and the most sensitive flowers of ethylene gas are carnations. Never place a bowl of fruit next to a vase of flowers. Always separate your vegetables from your fruits. It is commercially used in the horticulture industry to hasten the ripening of bananas, or inducing flowering of bromeliads. However, in some cases it may be detrimental by reducing the shelf life of some products such as flowers, pot plants, or kiwi fruit.

"Ethylene has been used in practice since the ancient Egyptians, who would gas figs in order to stimulate ripening. The ancient Chinese would burn incense in closed rooms to enhance the ripening of pears. In 1864, it was discovered that gas leaks from street lights led to stunting of growth, twisting of plants, and abnormal thickening of stems (the triple response)[see plant senescence](Arteca, 1996; Salisbury and Ross, 1992). In 1901, a Russian scientist named Dimitry Neljubow showed that the active component was ethylene (Neljubow, 1901). Doubt discovered that ethylene stimulated abscission in 1917 (Doubt, 1917). It wasn't until 1934 that Gane reported that plants synthesize ethylene (Gane, 1934). In 1935, Crocker proposed that ethylene was the plant hormone responsible for fruit ripening as well as inhibition of vegetative tissues (Crocker, 1935).

Because Nicotiana benthamiana leaves are susceptible to injuries, they are used in plant physiology practicals to study ethylene secretion.

Ethylene biosynthesis in plants

All plant tissues are able to produce ethylene, although the production rate is normally low.

"Ethylene production is regulated by a variety of developmental and environmental factors. During the life of the plant, ethylene production is induced during certain stages of growth such as germination, ripening of fruits, abscission of leaves, and senescence of flowers. Ethylene production can also be induced by a variety of external aspects such as mechanical wounding, environmental stresses, and certain chemicals including auxin and other regulators"[15]

The biosynsthesis of the hormone starts with conversion of the aminoacid methionine to S-adenosyl-L- methionine (SAM, also called Adomet) by the enzyme Met Adenosyltransferase. SAM is then converted to 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic-acid (ACC) by the enzyme ACC synthase (ACS); the activity of ACS is the rate-limiting step in ethylene production, therefore regulation of this enzyme is key for the ethylene biosynthesis. The final step requires oxygen and involves the action of the enzyme ACC-oxidase (ACO), formerly known as the Ethylene Forming Enzyme (EFE).

The pathway can be represented as follows:

Methionine —> SAM —> ACC —> Ethylene

Ethylene biosynthesis can be induced by endogenous or exogenous ethylene. ACC synthesis increases with high levels of auxins, specially Indol Acetic Acid (IAA), and cytokinins. ACC synthase is inhibited by abscisic acid.

Environmental and biological triggers of ethylene

Environmental cues can induce the biosynthesis of the plant hormone. Flooding, drought, chilling, wounding, and pathogen attack can induce the ethylene formation in the plant.

In flooding, root suffers from anoxia, leading to the synthesis of the 1-Aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC). As it lacks of oxygen, ACC is transported upwards in the plant and then oxidized in leaves. The product, the ethylene causes the epinasty of the leaves.

One speculation recently put forth for epinasty[16] is the downward pointing leaves may act as pump handles in the wind. The ethylene may or may not additionally induce the growth of a valve in the xylem, but the idea is that the plant would harness the power of the wind to pump out more water from the roots of the plants than would normally happen with transpiration.

Physiological responses of plants

Like the other plant hormones, ethylene is considered to have pleiotropic effects. This essentially means that it is thought that at least some of the effects of the hormone are unrelated. What is actually caused by the gas may depend on the tissue affected as well as environmental conditions. In the evolution of plants, ethylene would simply be a message that was coopted for unrelated uses by plants during different periods of the evolutionary development.

Some Plant Ethylene Characteristics

- Rapidly diffuses because it is a gas

- Synthesized in nodes of stems

- Synthesized during germination

- Synthesis is stimulated by auxin and maybe cytokinin as well

- Ethylene levels are decreased by light

- The flooding of roots stimulates the production of ACC which travels through the xylem to the stem and leaves where it is converted to the gas

- In pollination, when the pollen reaches the stigma, the precursor of the ethylene, ACC, is secreted to the petal, the ACC releases ethylene with ACC oxidase.

List of Plant Responses to Ethylene

- Stimulates leaf and flower senescence

- Stimulates senescence of mature xylem cells in preparation for plant use

- Inhibits shoot growth except in some habitually flooded plants like rice

- Induces leaf abscission

- Induces seed germination

- Induces root hair growth – increasing the efficiency of water and mineral absorption

- Induces the growth of adventitious roots during flooding

- Stimulates epinasty – leaf petiole grows out, leaf hangs down and curls into itself

- Stimulates fruit ripening

- Induces a climacteric rise in respiration in some fruit which causes a release of additional ethylene. This can be the one bad apple in a barrel spoiling the rest phenomenon.

- Affects neighboring individuals

- Disease/wounding resistance

- Triple response when applied to seedlings – stem elongation slows, the stem thickens, and curvature causes the stem to start growing horizontally. This strategy is thought to allow a seedling grow around an obstacle

- Inhibits stem growth outside of seedling stage

- Stimulates stem and cell broadening and lateral branch growth also outside of seedling stage

- Interference with auxin transport (with high auxin concentrations)

- Inhibits stomatal closing except in some water plants or habitually flooded ones such as some rice varieties, where the opposite occurs (conserving CO2 and O2)

- Where ethylene induces stomatal closing, it also induces stem elongation

- Induces flowering in pineapples

Effects on humans

Ethylene is colorless, has a pleasant sweet faint odor, and has a slightly sweet taste, and as it enhances fruit ripening, assists in the development of odour-active aroma volatiles (especially esters), which are responsible for the specific smell of each kind of flower or fruit. In high concentrations it can cause nausea. Its use in the food industry to induce ripening of fruit and vegetables, can lead to accumulation in refrigerator crispers, accelerating spoilage of these foods when compared with naturally ripened products.

Ethylene has long been in use as an inhalatory anaesthetic. It shows little or no carcinogenic or mutagenic properties, and although there may be moderate hyperglycemia, post operative nausea, whilst higher than nitrous oxide is less than in the use of cyclopropane. During the induction and early phases, blood pressure may rise a little, but this effect may be due to patient anxiety, as blood pressure quickly returns to normal. Cardiac arrythmias are infrequent and cardio-vascular effects are benign. Exposure at 37.5% for 15 minutes may result in marked memory disturbances. Humans exposed to as much as 50% ethylene in air, whereby the oxygen availability is decreased to 10%, experience a complete loss of consciousness and may subsequently die. Effects of exposure seem related to the issue of oxygen deprivation.

In mild doses, ethylene produces states of euphoria, associated with stimulus to the pleasure centres of the human brain. It has been hypothesised that human liking for the odours of flowers is due in part to a mild action of ethylene associated with the plant. Many geologists and scholars believe that the famous Greek Oracle at Delphi (the Pythia) went into her trance-like state as an affect of ethylene rising from ground faults.[11]

In air, ethylene acts primarily as an asphyxiant. Concentrations of ethylene required to produce any marked physiological effect will reduce the oxygen content to such a low level that life cannot be supported. For example, air containing 50% of ethylene will contain only about 10% oxygen.

Loss of consciousness results when the air contains about 11% of oxygen. Death occurs quickly when the oxygen content falls to 8% or less. There is no evidence to indicate that prolonged exposure to low concentrations of ethylene can result in chronic effects. Prolonged exposure to high concentrations may cause permanent effects because of oxygen deprivation.

Ethylene has a very low order of systemic toxicity. When used as a surgical anesthetic, it is always administered with oxygen with an increased risk of fire. In such cases, however, it acts as a simple, rapid anesthetic having a quick recovery. Prolonged inhalation of about 85% in oxygen is slightly toxic, resulting in a slow fall in the blood pressure; at about 94% in oxygen, ethylene is acutely fatal.

See also

| Alkenes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ethylene |

| |

Propylene |

| |

Butylene |

| |

Pentylene |

| |

Hexylene |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Functional groups |

|---|

| Chemical class: Alcohol • Aldehyde • Alkane • Alkene • Alkyne • Amide • Amine • Azo compound • Benzene derivative • Carboxylic acid • Cyanate • Ester • Ether • Haloalkane • Imine • Isocyanide • Isocyanate • Ketone • Nitrile • Nitro compound • Nitroso compound • Peroxide • Phosphoric acid • Pyridine derivative • Sulfone • Sulfonic acid • Sulfoxide • Thioether • Thiol • Toluene derivative |

| ||||||||

| Plant hormones | edit |

|

Abscisic acid - Auxins - Cytokinins - Ethylene (Ethene) - Gibberellins Brassinosteroids - Jasmonates - Salicylic acid |

Notes

- ↑ Merck. 2001. The Merck Index. 13th Edition. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co. ISBN 0-911910-13-1

- ↑ Wang K., H. Li, J. Ecker. Ethylene biosynthesis and signaling networks. Plant Cell. 14 Suppl:S131-51.

- ↑ 2006. Production: Growth is the Norm. Chemical and Engineering News. p. 59.

- ↑ Hofmann, A.W. 1866. Hofmann's Proposal for Systematic Nomenclature of the Hydrocarbons : "On the Action of Trichloride of Phosphorus on the Salts of the Aromatic Monamines". Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ IUPAC nomenclature rule A-3.1 (1979). Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ Footnote to IUPAC nomenclature rule R-9.1, table 19(b). Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ Ethylene:UV/Visible Spectrum. NIST Webbook. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 Kniel, Ludwig. 1980. Ethylene Keystone to the Petrochemical Industry. New York, NY: Marcel Dekker. ISBN 0-8247-6914-7

- ↑ Elschenbroich, C.; A. Salzer. 2006. Organometallics : A Concise Introduction (2nd Ed). Weinheim, Germany: Wiley-VCH. ISBN 3-527-28165-7.

- ↑ Crimmins, M.T.; A.S. Kim-Meade. 2004. "Ethylene" in Encyclopedia of Reagents for Organic Synthesis (Ed: L. Paquette). New York, NY: J. Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Roach, John. 2001. Delphic Oracle's Lips May Have Been Loosened by Gas Vapors. National Geographic. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ Transformerworld Tutorial No. 3. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- ↑ Chow B., P. McCourt. 2006. Plant hormone receptors: perception is everything. Genes Dev. 20:15:1998-2008.

- ↑ De Paepe A. , D. Van der Straeten. 2005. Ethylene biosynthesis and signaling: an overview. Vitam Horm. 72:399-430.

- ↑ Yang, S.F., and N.E. Hoffman P. 1984. Ethylene biosynthesis and its regulation in higher plants. Ann. Rev. Plant Physiol. 35:155-89.

- ↑ Epinasty. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- McMurry, John. 2004. Organic Chemistry. 6th ed. Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0534420052.

- Morrison, Robert T., and Robert N. Boyd. 1992. Organic Chemistry. 6th ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-643669-2.

- Solomons, T.W. Graham, and Fryhle, Craig B. 2004. Organic Chemistry. 8th ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. ISBN 0471417998.

External links

- International Chemical Safety Card 0475. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- European Chemicals Bureau. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

- Speculations Towards a General Plant Hormone Theory. Retrieved September 12, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.