Mass spectrometry

Mass spectrometry is an analytical technique that identifies the chemical composition of a compound or sample based on the mass-to-charge ratio of charged particles.[1] A sample undergoes chemical fragmentation forming charged particles (ions). The ratio of charge to mass of the particles is calculated by passing them through electric and magnetic fields in an instrument called a mass spectrometer.

The design of a mass spectrometer has three essential modules: an ion source, which transforms the molecules in a sample into ionized fragments; a mass analyzer, which sorts the ions by their masses by applying electric and magnetic fields; and a detector, which measures the value of some indicator quantity and thus provides data for calculating the abundances of each ion fragment present. The technique has both qualitative and quantitative uses, such as identifying unknown compounds, determining the isotopic composition of elements in a compound, determining the structure of a compound by observing its fragmentation, quantifying the amount of a compound in a sample, studying the fundamentals of gas phase ion chemistry (the chemistry of ions and neutrals in a vacuum), and determining other physical, chemical, or biological properties of compounds.

Etymology

The word spectrograph has been used since 1884 as an "International Scientific Vocabulary".[2] The linguistic roots, a combination and removal of bound morphemes and free morphemes, are closely related to the terms spectr-um and phot-ograph-ic plate.[3] In fact, early spectrometry devices that measured the mass-to-charge ratio of ions were called mass spectrographs because they were instruments that recorded a spectrum of mass values on a photographic plate.[4][5] A mass spectroscope is similar to a mass spectrograph except that the beam of ions is directed onto a phosphor screen.[6] A mass spectroscope configuration was used in early instruments when it was desired that the effects of adjustments be quickly observed. Once the instrument was properly adjusted, a photographic plate was inserted and exposed. The term mass spectroscope continued to be used even though the direct illumination of a phosphor screen was replaced by indirect measurements with an oscilloscope.[7] The use of the term mass spectroscopy is now discouraged due to the possibility of confusion with light spectroscopy.[1][8][1] Mass spectrometry is often abbreviated as mass-spec or simply as MS.[1] Thomson has also noted that a mass spectroscope is similar to a mass spectrograph except that the beam of ions is directed onto a phosphor screen.[6] The suffix -scope here denotes the direct viewing of the spectra (range) of masses.

History

In 1886, Eugen Goldstein observed rays in gas discharges under low pressure that travelled through the channels in a perforated cathode toward the anode, in the opposite direction to the negatively charged cathode rays. Goldstein called these positively charged anode rays "Kanalstrahlen"; the standard translation of this term into English is "canal rays." Wilhelm Wien found that strong electric or magnetic fields deflected the canal rays and, in 1899, constructed a device with parallel electric and magnetic fields that separated the positive rays according to their charge-to-mass ratio (Q/m). Wien found that the charge-to-mass ratio depended on the nature of the gas in the discharge tube. English scientist J.J. Thomson later improved on the work of Wien by reducing the pressure to create a mass spectrograph.

Some of the modern techniques of mass spectrometry were devised by Arthur Jeffrey Dempster and F.W. Aston in 1918 and 1919 respectively. In 1989, half of the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Hans Dehmelt and Wolfgang Paul for the development of the ion trap technique in the 1950s and 1960s. In 2002, the Nobel Prize in Chemistry was awarded to John Bennett Fenn for the development of electrospray ionization (ESI) and Koichi Tanaka for the development of soft laser desorption (SLD) in 1987. However earlier, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI), was developed by Franz Hillenkamp and Michael Karas; this technique has been widely used for protein analysis.[9]

Simplified example

The following example describes the operation of a spectrometer mass analyzer, which is of the sector type. (Other analyzer types are treated below.) Consider a sample of sodium chloride (table salt). In the ion source, the sample is vaporized (turned into gas) and ionized (transformed into electrically charged particles) into sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-) ions. Sodium atoms and ions are monoisotopic, with a mass of about 23 amu. Chloride atoms and ions come in two isotopes with masses of approximately 35 amu (at a natural abundance of about 75 percent) and approximately 37 amu (at a natural abundance of about 25 percent). The analyzer part of the spectrometer contains electric and magnetic fields, which exert forces on ions traveling through these fields. The speed of a charged particle may be increased or decreased while passing through the electric field, and its direction may be altered by the magnetic field. The magnitude of the deflection of the moving ion's trajectory depends on its mass-to-charge ratio. By Newton's second law of motion, lighter ions get deflected by the magnetic force more than heavier ions. The streams of sorted ions pass from the analyzer to the detector, which records the relative abundance of each ion type. This information is used to determine the chemical element composition of the original sample (i.e. that both sodium and chlorine are present in the sample) and the isotopic composition of its constituents (the ratio of 35Cl to 37Cl).

Instrumentation

Ion source technologies

The ion source is the part of the mass spectrometer that ionizes the material under analysis (the analyte). The ions are then transported by magnetic or electric fields to the mass analyzer.

Techniques for ionization have been key to determining what types of samples can be analyzed by mass spectrometry. Electron ionization and chemical ionization are used for gases and vapors. In chemical ionization sources, the analyte is ionized by chemical ion-molecule reactions during collisions in the source. Two techniques often used with liquid and solid biological samples include electrospray ionization (invented by John Fenn) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI, developed by K. Tanaka and separately by M. Karas and F. Hillenkamp). Inductively coupled plasma sources are used primarily for metal analysis on a wide array of sample types. Others include glow discharge, field desorption (FD), fast atom bombardment (FAB), thermospray, desorption/ionization on silicon (DIOS), Direct Analysis in Real Time (DART), atmospheric pressure chemical ionization (APCI), secondary ion mass spectrometry (SIMS), spark ionization and thermal ionization.[10] Ion Attachment Ionization is a newer soft ionization technique that allows for fragmentation free analysis.

Mass analyzer technologies

Mass analyzers separate the ions according to their mass-to-charge ratio. The following two laws govern the dynamics of charged particles in electric and magnetic fields in vacuum:

- (Lorentz force law)

- (Newton's second law of motion)

where F is the force applied to the ion, m is the mass of the ion, a is the acceleration, Q is the ion charge, E is the electric field, and v x B is the vector cross product of the ion velocity and the magnetic field

Equating the above expressions for the force applied to the ion yields:

This differential equation is the classic equation of motion for charged particles. Together with the particle's initial conditions, it completely determines the particle's motion in space and time in terms of m/Q. Thus mass spectrometers could be thought of as "mass-to-charge spectrometers." When presenting data, it is common to use the (officially) dimensionless m/z, where z is the number of elementary charges (e) on the ion (z=Q/e). This quantity, although it is informally called the mass-to-charge ratio, more accurately speaking represents the ratio of the mass number and the charge number, z.

There are many types of mass analyzers, using either static or dynamic fields, and magnetic or electric fields, but all operate according to the above differential equation. Each analyzer type has its strengths and weaknesses. Many mass spectrometers use two or more mass analyzers for tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS). In addition to the more common mass analyzers listed below, there are others designed for special situations.

Sector

A sector field mass analyzer uses an electric and/or magnetic field to affect the path and/or velocity of the charged particles in some way. As shown above, sector instruments bend the trajectories of the ions as they pass through the mass analyzer, according to their mass-to-charge ratios, deflecting the more charged and faster-moving, lighter ions more. The analyzer can be used to select a narrow range of m/z or to scan through a range of m/z to catalog the ions present.[11]

Time-of-flight

The time-of-flight (TOF) analyzer uses an electric field to accelerate the ions through the same potential, and then measures the time they take to reach the detector. If the particles all have the same charge, the kinetic energies will be identical, and their velocities will depend only on their masses. Lighter ions will reach the detector first.[12]

Quadrupole

Quadrupole mass analyzers use oscillating electrical fields to selectively stabilize or destabilize ions passing through a radio frequency (RF) quadrupole field. A quadrupole mass analyzer acts as a mass selective filter and is closely related to the Quadrupole ion trap, particularly the linear quadrupole ion trap except that it operates without trapping the ions and is for that reason referred to as a transmission quadrupole. A common variation of the quadrupole is the triple quadrupole.

Quadrupole ion trap

The quadrupole ion trap works on the same physical principles as the quadrupole mass analyzer, but the ions are trapped and sequentially ejected. Ions are created and trapped in a mainly quadrupole RF potential and separated by m/Q, non-destructively or destructively.

There are many mass/charge separation and isolation methods but most commonly used is the mass instability mode in which the RF potential is ramped so that the orbit of ions with a mass are stable while ions with mass become unstable and are ejected on the z-axis onto a detector.

Ions may also be ejected by the resonance excitation method, whereby a supplemental oscillatory excitation voltage is applied to the endcap electrodes, and the trapping voltage amplitude and/or excitation voltage frequency is varied to bring ions into a resonance condition in order of their mass/charge ratio.[13][14]

The cylindrical ion trap mass spectrometer is a derivative of the quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer.

Linear quadrupole ion trap

A linear quadrupole ion trap is similar to a quadrupole ion trap, but it traps ions in a two dimensional quadrupole field, instead of a three dimensional quadrupole field as in a quadrupole ion trap. Thermo Fisher's LTQ ("linear trap quadrupole") is an example of the linear ion trap.[15]

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance

Fourier transform mass spectrometry, or more precisely Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance MS, measures mass by detecting the image current produced by ions cyclotroning in the presence of a magnetic field. Instead of measuring the deflection of ions with a detector such as an electron multiplier, the ions are injected into a Penning trap (a static electric/magnetic ion trap) where they effectively form part of a circuit. Detectors at fixed positions in space measure the electrical signal of ions which pass near them over time, producing a periodic signal. Since the frequency of an ion's cycling is determined by its mass to charge ratio, this can be deconvoluted by performing a Fourier transform on the signal. FTMS has the advantage of high sensitivity (since each ion is "counted" more than once) and much higher resolution and thus precision.[16][17]

Ion cyclotron resonance (ICR) is an older mass analysis technique similar to FTMS except that ions are detected with a traditional detector. Ions trapped in a Penning trap are excited by an RF electric field until they impact the wall of the trap, where the detector is located. Ions of different mass are resolved according to impact time.

Very similar nonmagnetic FTMS has been performed, where ions are electrostatically trapped in an orbit around a central, spindle shaped electrode. The electrode confines the ions so that they both orbit around the central electrode and oscillate back and forth along the central electrode's long axis. This oscillation generates an image current in the detector plates which is recorded by the instrument. The frequencies of these image currents depend on the mass to charge ratios of the ions. Mass spectra are obtained by Fourier transformation of the recorded image currents.

Similar to Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometers, Orbitraps have a high mass accuracy, high sensitivity and a good dynamic range.[18]

Detector

The final element of the mass spectrometer is the detector. The detector records either the charge induced or the current produced when an ion passes by or hits a surface. In a scanning instrument, the signal produced in the detector during the course of the scan versus where the instrument is in the scan (at what m/Q) will produce a mass spectrum, a record of ions as a function of m/Q.

Typically, some type of electron multiplier is used, though other detectors including Faraday cups and ion-to-photon detectors are also used. Because the number of ions leaving the mass analyzer at a particular instant is typically quite small, considerable amplification is often necessary to get a signal. Microchannel Plate Detectors are commonly used in modern commercial instruments.[19] In FTMS and Orbitraps, the detector consists of a pair of metal surfaces within the mass analyzer/ion trap region which the ions only pass near as they oscillate. No DC current is produced, only a weak AC image current is produced in a circuit between the electrodes. Other inductive detectors have also been used.[20]

Tandem mass spectrometry

A tandem mass spectrometer is one capable of multiple rounds of mass spectrometry, usually separated by some form of molecule fragmentation. For example, one mass analyzer can isolate one peptide from many entering a mass spectrometer. A second mass analyzer then stabilizes the peptide ions while they collide with a gas, causing them to fragment by collision-induced dissociation (CID). A third mass analyzer then sorts the fragments produced from the peptides. Tandem MS can also be done in a single mass analyzer over time, as in a quadrupole ion trap. There are various methods for fragmenting molecules for tandem MS, including collision-induced dissociation (CID), electron capture dissociation (ECD), electron transfer dissociation (ETD), infrared multiphoton dissociation (IRMPD) and blackbody infrared radiative dissociation (BIRD). An important application using tandem mass spectrometry is in protein identification.[21]

Tandem mass spectrometry enables a variety of experimental sequences. Many commercial mass spectrometers are designed to expedite the execution of such routine sequences as single reaction monitoring (SRM), multiple reaction monitoring (MRM), and precursor ion scan. In SRM, the first analyzer allows only a single mass through and the second analyzer monitors for a single user defined fragment ion. MRM allows for multiple user defined fragment ions. SRM and MRM are most often used with scanning instruments where the second mass analysis event is duty cycle limited. These experiments are used to increase specificity of detection of known molecules, notably in pharmacokinetic studies. Precursor ion scan refers to monitoring for a specific loss from the precursor ion. The first and second mass analyzers scan across the spectrum as partitioned by a user defined m/z value. This experiment is used to detect specific motifs within unknown molecules.

Common mass spectrometer configurations and techniques

When a specific configuration of source, analyzer, and detector becomes conventional in practice, often a compound acronym arises to designate it, and the compound acronym may be more well known among nonspectrometrists than the component acronyms. The epitome of this is MALDI-TOF, which simply refers to combining a Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization source with a Time-of-flight mass analyzer. The MALDI-TOF moniker is more widely recognized by the non-mass spectrometrist scientist than MALDI or TOF individually. Other examples include inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (ICP-MS), accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS), Thermal ionization-mass spectrometry (TIMS) and spark source mass spectrometry (SSMS). Sometimes the use of the generic "MS" actually connotes a very specific mass analyzer and detection system, as is the case with AMS, which is always sector based.

Certain applications of mass spectrometry have developed monikers that although strictly speaking they would seem to refer to a broad application, in practice have come instead to connote a specific or a limited number of instrument configurations. An example of this is isotope ratio mass spectrometry (IRMS), which refers in practice to the use of a limited number of sector based mass analyzers; this name is used to refer to both the application and the instrument used for the application.

Chromatographic techniques combined with mass spectrometry

An important enhancement to the mass resolving and mass determining capabilities of mass spectrometry is using it in tandem with chromatographic separation techniques.

Gas chromatography

A common combination is gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS or GC-MS). In this technique, a gas chromatograph is used to separate different compounds. This stream of separated compounds is fed online into the ion source, a metallic filament to which voltage is applied. This filament emits electrons which ionize the compounds. The ions can then further fragment, yielding predictable patterns. Intact ions and fragments pass into the mass spectrometer's analyzer and are eventually detected.[22]

Liquid chromatography

Similar to gas chromatography MS (GC/MS), liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (LC/MS or LC-MS) separates compounds chromatographically before they are introduced to the ion source and mass spectrometer. It differs from GC/MS in that the mobile phase is liquid, usually a mixture of water and organic solvents, instead of gas. Most commonly, an electrospray ionization source is used in LC/MS. There are also some newly developed ionization techniques like laser spray.

Ion mobility

Ion mobility spectrometry/mass spectrometry (IMS/MS or IMMS) is a technique where ions are first separated by drift time through some neutral gas under an applied electrical potential gradient before being introduced into a mass spectrometer.[23] Drift time is a measure of the radius relative to the charge of the ion. The duty cycle of IMS (the time over which the experiment takes place) is longer than most mass spectrometric techniques, such that the mass spectrometer can sample along the course of the IMS separation. This produces data about the IMS separation and the mass-to-charge ratio of the ions in a manner similar to LC/MS.[24]

The duty cycle of IMS is short relative to liquid chromatography or gas chromatography separations and can thus be coupled to such techniques, producing triple modalities such as LC/IMS/MS.[25]

Data and analysis

Data representations

Mass spectrometry produces various types of data. The most common data representation is the mass spectrum.

Certain types of mass spectrometry data are best represented as a mass chromatogram. Types of chromatograms include selected ion monitoring (SIM), total ion current (TIC), and selected reaction monitoring chromatogram (SRM), among many others.

Other types of mass spectrometry data are well represented as a three dimensional contour map. In this form, the mass-to-charge, m/z is on the x-axis, intensity the y-axis, and an additional experimental parameter, such as time, is recorded on the z-axis.

Data analysis

Basics

Mass spectrometry data analysis is a complicated subject matter that is very specific to the type of experiment producing the data. There are general subdivisions of data that are fundamental to understand any data.

Many mass spectrometers work in either negative ion mode or positive ion mode. It is very important to know whether the observed ions are negatively or positively charged. This is often important in determining the neutral mass but it also indicates something about the nature of the molecules.

Different types of ion source result in different arrays of fragments produced from the original molecules. An electron ionization source produces many fragments and mostly odd electron species with one charge, whereas an electrospray source usually produces quasimolecular even electron species that may be multiply charged. Tandem mass spectrometry purposely produces fragment ions post-source and can drastically change the sort of data achieved by an experiment.

By understanding the origin of a sample, certain expectations can be assumed as to the component molecules of the sample and their fragmentations. A sample from a synthesis/manufacturing process will likely contain impurities chemically related to the target component. A relatively crudely prepared biological sample will likely contain a certain amount of salt, which may form adducts with the analyte molecules in certain analyses.

Results can also depend heavily on how the sample was prepared and how it was run/introduced. An important example is the issue of which matrix is used for MALDI spotting, since much of the energetics of the desorption/ionization event is controlled by the matrix rather than the laser power. Sometimes samples are spiked with sodium or another ion-carrying species to produce adducts rather than a protonated species.

The greatest source of trouble when non-mass spectrometrists try to conduct mass spectrometry on their own or collaborate with a mass spectrometrist is inadequate definition of the research goal of the experiment. Adequate definition of the experimental goal is a prerequisite for collecting the proper data and successfully interpreting it. Among the determinations that can be achieved with mass spectrometry are molecular mass, molecular structure, and sample purity. Each of these questions requires a different experimental procedure. Simply asking for a "mass spec" will most likely not answer the real question at hand.

Interpretation of mass spectra

Since the precise structure or peptide sequence of a molecule is deciphered through the set of fragment masses, the interpretation of mass spectra requires combined use of various techniques. Usually the first strategy for identifying an unknown compound is to compare its experimental mass spectrum against a library of mass spectra. If the search comes up empty, then manual interpretation[26] or software assisted interpretation of mass spectra are performed. Computer simulation of ionization and fragmentation processes occurring in mass spectrometer is the primary tool for assigning structure or peptide sequence to a molecule. An a priori structural information is fragmented in silico and the resulting pattern is compared with observed spectrum. Such simulation is often supported by a fragmentation library[27] that contains published patterns of known decomposition reactions. Software taking advantage of this idea has been developed for both small molecules and proteins.

Another way of interpreting mass spectra involves spectra with accurate mass. A mass-to-charge ratio value (m/z) with only integer precision can represent an immense number of theoretically possible ion structures. More "accurate" (actually, "precise") mass figures significantly reduce the number of candidate molecular formulas, albeit each can still represent large number of structurally diverse compounds. A computer algorithm called formula generator calculates all molecular formulas that theoretically fit a given mass with specified tolerance.

A recent technique for structure elucidation in mass spectrometry, called precursor ion fingerprinting identifies individual pieces of structural information by conducting a search of the tandem spectra of the molecule under investigation against a library of the product-ion spectra of structurally characterized precursor ions.

Applications

Isotope ratio MS: isotope dating and tracking

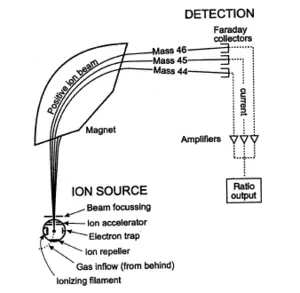

Mass spectrometry is also used to determine the isotopic composition of elements within a sample. Differences in mass among isotopes of an element are very small, and the less abundant isotopes of an element are typically very rare, so a very sensitive instrument is required. These instruments, sometimes referred to as isotope ratio mass spectrometers (IR-MS), usually use a single magnet to bend a beam of ionized particles towards a series of Faraday cups which convert particle impacts to electric current. A fast on-line analysis of deuterium content of water can be done using Flowing afterglow mass spectrometry, FA-MS. Probably the most sensitive and accurate mass spectrometer for this purpose is the accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS). Isotope ratios are important markers of a variety of processes. Some isotope ratios are used to determine the age of materials for example as in carbon dating. Labeling with stable isotopes is also used for protein quantification. (see Protein quantitation below)

Trace gas analysis

Several techniques use ions created in a dedicated ion source injected into a flow tube or a drift tube: selected ion flow tube (SIFT-MS), and proton transfer reaction (PTR-MS), are variants of chemical ionization dedicated for trace gas analysis of air, breath or liquid headspace using well defined reaction time allowing calculations of analyte concentrations from the known reaction kinetics without the need for internal standard or calibration.

Atom probe

An atom probe is an instrument that combines time-of-flight mass spectrometry and field ion microscopy (FIM) to map the location of individual atoms.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetics is often studied using mass spectrometry because of the complex nature of the matrix (often blood or urine) and the need for high sensitivity to observe low dose and long time point data. The most common instrumentation used in this application is LC-MS with a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer. Tandem mass spectrometry is usually employed for added specificity. Standard curves and internal standards are used for quantitation of usually a single pharmaceutical in the samples. The samples represent different time points as a pharmaceutical is administered and then metabolized or cleared from the body. Blank or t=0 samples taken before administration are important in determining background and insuring data integrity with such complex sample matrices. Much attention is paid to the linearity of the standard curve; however it is not uncommon to use curve fitting with more complex functions such as quadratics since the response of most mass spectrometers is less than linear across large concentration ranges.[28][29][30]

There is currently considerable interest in the use of very high sensitivity mass spectrometry for microdosing studies, which are seen as a promising alternative to animal experimentation.

Protein characterization

Mass spectrometry is an important emerging method for the characterization of proteins. The two primary methods for ionization of whole proteins are electrospray ionization (ESI) and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI). In keeping with the performance and mass range of available mass spectrometers, two approaches are used for characterizing proteins. In the first, intact proteins are ionized by either of the two techniques described above, and then introduced to a mass analyzer. This approach is referred to as "top-down" strategy of protein analysis. In the second, proteins are enzymatically digested into smaller peptides using proteases such as trypsin or pepsin, either in solution or in gel after electrophoretic separation. Other proteolytic agents are also used. The collection of peptide products are then introduced to the mass analyzer. When the characteristic pattern of peptides is used for the identification of the protein the method is called peptide mass fingerprinting (PMF), if the identification is performed using the sequence data determined in tandem MS analysis it is called de novo sequencing. These procedures of protein analysis are also referred to as the "bottom-up" approach.

Space exploration

As a standard method for analysis, mass spectrometers have reached other planets and moons. Two were taken to Mars by the Viking program. In early 2005 the Cassini-Huygens mission delivered a specialized GC-MS instrument aboard the Huygens probe through the atmosphere of Titan, the largest moon of the planet Saturn. This instrument analyzed atmospheric samples along its descent trajectory and was able to vaporize and analyze samples of Titan's frozen, hydrocarbon covered surface once the probe had landed. These measurements compare the abundance of isotope(s) of each particle comparatively to earth's natural abundance.[31]

Mass spectrometers are also widely used in space missions to measure the composition of plasmas. For example, the Cassini spacecraft carries the Cassini Plasma Spectrometer (CAPS),[32] which measures the mass of ions in Saturn's magnetosphere.

Respired gas monitor

Mass spectrometers were used in hospitals for respiratory gas analysis beginning around 1975 through the end of the century. Some are likely still in use but none are currently being manufactured.[33]

Found mostly in the operating room, they were a part of a complex system in which respired gas samples from patients undergoing anesthesia were drawn into the instrument through a valve mechanism designed to sequentially connect up to 32 rooms to the mass spectrometer. A computer directed all operations of the system. The data collected from the mass spectrometer was delivered to the individual rooms for the anesthesiologist to use.

This magnetic sector mass spectrometer's uniqueness may have been the fact that a plane of detectors, each purposely positioned to collect all of the ion species expected to be in the samples, allowed the instrument to simultaneously report all of the patient respired gases. Although the mass range was limited to slightly over 120 u, fragmentation of some of the heavier molecules negated the need for a higher detection limit.[34]

See also

- Atom

- Atomic mass

- Mass spectrometer

- Molecular mass

- Molecule

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 O. David. Sparkman, 2000. Mass spectrometry desk reference. (Pittsburgh, PA: Global View Pub. ISBN 0966081323).

- ‚ÜĎ Definition of spectrograph. Merriam Webster. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Douglas Harper, 2001. Spectrum. Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved October 17, 2008. Note: This part of the article only makes descriptive claims about the information found in the primary source, the accuracy and applicability of which is easily verifiable by any reasonable, educated person without specialist knowledge.

- ‚ÜĎ Gordon Squires, 1998. Francis Aston and the mass spectrograph. Dalton Transactions 3893‚Äď3900. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ K.M. Downard, 2007. Francis William Aston - the man behind the mass spectrograph. European Journal of Mass Spectrometry 13(3):177‚Äď190.

- ‚ÜĎ 6.0 6.1 J.J. Thomson, 1913. Rays Of Positive Electricity and Their Application to Chemical Analysis. (London, UK: Longman's Green and Company.) Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ William Siri, 1947. Mass spectroscope for analysis in the low-mass range. Review of Scientific Instruments 18(8):540‚Äď545. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Phil Price, 1991. Standard definitions of terms relating to mass spectrometry. A report from the Committee on Measurements and Standards of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry. 2(4):336‚Äď348.

- ‚ÜĎ Michael G. Grayson, 2002. Measuring Mass: From Positive Rays to Proteins. (Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Press. ISBN 0941901319.)

- ‚ÜĎ A.P. Bruins, 1991. Mass spectrometry with ion sources operating at atmospheric pressure. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 10(1):53‚Äď77.

- ‚ÜĎ John S. Cottrell and Roger J Greathead. 1986. Extending the mass range of a sector mass spectrometer. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 5:215-247.

- ‚ÜĎ H. Wollnik, 1993. Time-of-flight mass analyzers. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 12:89-114.

- ‚ÜĎ W. Paul & H. Steinwedel 1953. Ein neues Massenspektrometer ohne Magnetfeld. RZeitschrift f√ľr Naturforschung A. 8(7):448-450.

- ‚ÜĎ R.E. March, 2000. Quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometry: a view at the turn of the century. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry 200(1-3):285‚Äď312.

- ‚ÜĎ Jae C. Schwartz, Michael W. Senko, and John E. P. Syka. 2002. A two-dimensional quadrupole ion trap mass spectrometer. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 13(6):659‚Äď669.

- ‚ÜĎ M.B. Comisarow and A.G. Marshall. 1974. Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance spectroscopy. Chemical Physics Letters 25(2):282‚Äď283.

- ‚ÜĎ A.G. Marshall, C.L. Hendrickson, and G.S. Jackson. 1998. Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometry: a primer. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 17(1):1‚Äď34.

- ‚ÜĎ Q. Hu, R.J. Noll, H. Li, A. Makarov, M. Hardman, and R. G. Cooks. 2005. The Orbitrap: a new mass spectrometer. Journal of Mass Spectrometry 40(4):430‚Äď443.

- ‚ÜĎ F. Dubois, R. Knochenmuss, R. Zenobi, A. Brunelle, C. Deprun, and Y. L. Beyec. 1999. A comparison between ion-to-photon and microchannel plate detectors. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 13(9):786‚Äď791.

- ‚ÜĎ M.A. Park, J.H. Callahan and A. Vertes. 1994. An inductive detector for time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 8(4):317‚Äď322.

- ‚ÜĎ Robert K. Boyd, 1994. Linked-scan techniques for MS/MS using tandem-in-space instruments. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 13(5-6):359‚Äď410.

- ‚ÜĎ G.A. Eiceman, 2000. "Gas Chromatography" in R.A. Meyers, (ed.) 2000. Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry: Applications, Theory, and Instrumentation. (Chichester, UK: Wiley. ISBN 0471976709), 10627.

- ‚ÜĎ G.F. Verbeck, B.T. Ruotolo, H.A. Sawyer, K.J. Gillig, and D.H. Russell. 2002. A fundamental introduction to ion mobility mass spectrometry applied to the analysis of biomolecules. J Biomol Tech. 13(2):56-61.

- ‚ÜĎ L.M. Matz, G.R. Asbury and H.H. Hill. 2002. Two-dimensional separations with electrospray ionization ambient pressure high-resolution ion mobility spectrometry/quadrupole mass spectrometry. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry 16(7):670‚Äď675.

- ‚ÜĎ Rena A. Sowell, Stormy L. Koeniger, Stephen J. Valentine, Myeong Hee Moon, and David E. Clemmer. 2004. Nanoflow LC/IMS-MS and LC/IMS-CID/MS of Protein Mixtures. Journal of the American Society for Mass Spectrometry 15(9):1341‚Äď1353.

- ‚ÜĎ FrantiŇ°ek Tureńćek, and Fred W. McLafferty. 1993. Interpretation of mass spectra. (Mill Valley, CA: University Science Books. ISBN 0935702253).

- ‚ÜĎ R. Mistrik, 2004. A New Concept for the Interpretation of Mass Spectra Based on a Combination of a Fragmentation Mechanism Database and a Computer Expert System. in A.E. Ashcroft, G. Brenton, and J.J. Monaghan, (eds.) 2004. Advances in Mass Spectrometry, vol 16. (Oxford, UK: Elsevier. ISBN 9780444515285), 821. Retrieved October 18, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Y. Hsieh, and W.A. Korfmacher. 2006. Increasing Speed and Throughput When Using HPLC-MS/MS Systems for Drug Metabolism and Pharmacokinetic Screening, Current Drug Metabolism 7(5):479-489.

- ‚ÜĎ T.R. Covey, E.D. Lee, and J.D. Henion. 1986. High-speed liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry for the determination of drugs in biological samples. Anal Chem. 58:2453-2460.

- ‚ÜĎ T.R. Covey, et al. 1985. Thermospray liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry determination of drugs and their metabolites in biological fluids. Anal Chem. 57(2):474-481.

- ‚ÜĎ S. Petrie, and D.K. Bohme. 2007. Ions in space. Mass Spectrometry Reviews 26(2):258‚Äď280.

- ‚ÜĎ Cassini Plasma Spectrometer. Southwest Research Institute. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ J.B. Riker & B. Haberman. 1976. Expired gas monitoring by mass spectrometry in a respiratory intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 4(5):223-229. Retrieved October 17, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ J.W.W. Gothard, C.M. Busst, M.A. Branthwaite, N.J.H. Davies, and D.M. Denison. 1980. Applications of respiratory mass spectrometry to intensive care. Anaesthesia 35(9):890‚Äď895.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ashcroft, A.E., G. Brenton, and J.J. Monaghan eds. 2004. Advances in Mass Spectrometry, vol 16. Oxford, UK: Elsevier. ISBN 9780444515285.

- Dass, Chhabil. 2001. Principles and practice of biological mass spectrometry. New York, NY: John Wiley. ISBN 0471330531.

- de Hoffman, Edmond and Vincent Stroobant. 2001. Mass Spectrometry: Principles and Applications, 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 0471485667.

- Downard, Kevin. 2004. Mass Spectrometry - A Foundation Course. Cambridge UK: Royal Society of Chemistry. ISBN 0854046096.

- Eiceman, G.A. 2000. "Gas Chromatography" in R.A. Meyers, (ed.) 2000. Encyclopedia of Analytical Chemistry: Applications, Theory, and Instrumentation. Chichester, UK: Wiley. ISBN 0471976709.

- Grayson, Michael G. 2002. Measuring Mass: From Positive Rays to Proteins. Philadelphia, PA: Chemical Heritage Press. ISBN 0941901319.

- Gross, J√ľrgen H. 2004. Mass Spectrometry: A Textbook. Berlin, DE: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 3540407391.

- Muzikar, P. et al. 2003. Accelerator Mass Spectrometry in Geologic Research. Geological Society of America Bulletin 115:643-654.

- Siuzdak, Gary. 1996. Mass spectrometry for biotechnology. Boston, MA: Academic Press. ISBN 0126474710.

- Sparkman, David O. 2006. Mass Spectrometry Desk Reference. Pittsburgh, PA: Global View Pub. ISBN 0966081390.

- Tuniz, C. 1998. Accelerator mass spectrometry: ultrasensitive analysis for global science. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press. ISBN 0849345383.

- Tureńćek, FrantiŇ°ek, and Fred W. McLafferty. 1993. Interpretation of mass spectra. Sausalito, CA: University Science Books. ISBN 0935702253.

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2025.

- Mass spectrometer simulation An interactive application simulating the console of a mass spectrometer.

- American Society for Mass Spectrometry.

- International Mass Spectrometry Foundation.

| |||||

| |||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.