Difference between revisions of "Russian Federation" - New World Encyclopedia

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) |

Mike Butler (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 127: | Line 127: | ||

By the end of the tenth century, the [[Old Norse language|Norse]] minority had merged with the Slavic population, particularly among the aristocracy, which also absorbed [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] [[Christianity|Christian]] influences in the course of the multiple campaigns to loot [[Tsargrad]], or [[Constantinople]]. One such campaign claimed the life of the foremost Slavic [[druzhina]] leader, [[Svyatoslav I]], who was renowned for having crushed the power of the Khazars on the Volga. While the fortunes of the [[Byzantine Empire]] had been ebbing, its culture was a continuous influence on the development of Russia in its formative centuries. | By the end of the tenth century, the [[Old Norse language|Norse]] minority had merged with the Slavic population, particularly among the aristocracy, which also absorbed [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] [[Christianity|Christian]] influences in the course of the multiple campaigns to loot [[Tsargrad]], or [[Constantinople]]. One such campaign claimed the life of the foremost Slavic [[druzhina]] leader, [[Svyatoslav I]], who was renowned for having crushed the power of the Khazars on the Volga. While the fortunes of the [[Byzantine Empire]] had been ebbing, its culture was a continuous influence on the development of Russia in its formative centuries. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:sophia iznutri.jpg|thumb|left|300px|The Byzantine influence on Russian architecture is evident in [[Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kiev|Hagia Sophia in Kiev]], originally built in the 11th century by [[Yaroslav the Wise]].]] | |

Kievan Rus' is important for its introduction of a Slavic variant of the [[Eastern Orthodoxy|Eastern Orthodox]] religion, dramatically deepening a synthesis of Byzantine and Slavic cultures that defined Russian culture for the next thousand years. The region adopted [[Christianity]] in 988 by the official act of public [[Baptism of Kievan Rus'|baptism]] of Kiev inhabitants by [[Vladimir I of Kiev|Prince Vladimir I]]. Some years later the first code of laws, [[Russkaya Pravda]], was introduced. From the onset the Kievan princes followed the Byzantine example and kept the Church dependent on them, even for its revenues, so that the Russian Church and state were always closely linked. | Kievan Rus' is important for its introduction of a Slavic variant of the [[Eastern Orthodoxy|Eastern Orthodox]] religion, dramatically deepening a synthesis of Byzantine and Slavic cultures that defined Russian culture for the next thousand years. The region adopted [[Christianity]] in 988 by the official act of public [[Baptism of Kievan Rus'|baptism]] of Kiev inhabitants by [[Vladimir I of Kiev|Prince Vladimir I]]. Some years later the first code of laws, [[Russkaya Pravda]], was introduced. From the onset the Kievan princes followed the Byzantine example and kept the Church dependent on them, even for its revenues, so that the Russian Church and state were always closely linked. | ||

| − | |||

By the eleventh century, particularly during the reign of [[Yaroslav the Wise]], Kievan Rus' could boast an economy and achievements in architecture and literature superior to those that then existed in the western part of the continent. Compared with the languages of European Christendom, the [[Russian language]] was little influenced by the [[Greek language|Greek]] and [[Latin]] of early Christian writings. This was due to the fact that [[Church Slavonic]] was used directly in [[liturgy]] instead. | By the eleventh century, particularly during the reign of [[Yaroslav the Wise]], Kievan Rus' could boast an economy and achievements in architecture and literature superior to those that then existed in the western part of the continent. Compared with the languages of European Christendom, the [[Russian language]] was little influenced by the [[Greek language|Greek]] and [[Latin]] of early Christian writings. This was due to the fact that [[Church Slavonic]] was used directly in [[liturgy]] instead. | ||

| Line 144: | Line 143: | ||

===Russo-Tatar relations=== | ===Russo-Tatar relations=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Batukhan.jpg|thumb|left|300px| | + | [[Image:Batukhan.jpg|thumb|left|300px|[[Alexander Nevsky]] in the [[Golden Horde|Horde]].]] |

| − | + | [[Image:Semiradsky Aleksandr Nevsky v Orde.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Prince Michael of Chernigov was ordered to worship fire at the camp of Batu Khan. Mongols stabbed him to death for his refusal to renounce [[Christianity]] and take part in the pagan ritual.]] | |

| − | |||

After the fall of the [[Khazars]] in the tenth century, the middle Volga came to be dominated by the mercantile state of [[Volga Bulgaria]], the last vestige of [[Great Bulgaria|Greater Bulgaria]] centered at [[Phanagoria]]. In the tenth century, the Turkic population of Volga Bulgaria converted to [[Islam]], which facilitated its trade with the Middle East and Central Asia. In the wake of the [[Mongol invasion of Volga Bulgaria|Mongol invasions]] of the 1230s, Volga Bulgaria was absorbed by the [[Golden Horde]] and its population evolved into the modern [[Chuvash]]es and [[Tatars|Kazan Tatar]]s. | After the fall of the [[Khazars]] in the tenth century, the middle Volga came to be dominated by the mercantile state of [[Volga Bulgaria]], the last vestige of [[Great Bulgaria|Greater Bulgaria]] centered at [[Phanagoria]]. In the tenth century, the Turkic population of Volga Bulgaria converted to [[Islam]], which facilitated its trade with the Middle East and Central Asia. In the wake of the [[Mongol invasion of Volga Bulgaria|Mongol invasions]] of the 1230s, Volga Bulgaria was absorbed by the [[Golden Horde]] and its population evolved into the modern [[Chuvash]]es and [[Tatars|Kazan Tatar]]s. | ||

| Line 162: | Line 160: | ||

===Ivan III, the Great=== | ===Ivan III, the Great=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Kivshenko Ivan III tears off the khans missive letter.jpg|thumb|right| | + | [[Image:Kivshenko Ivan III tears off the khans missive letter.jpg|thumb|right|350px|Ivan III tears off the Khan's missive letter demanding the tribute in from of Khan's mission]] |

In the fifteenth century, the grand princes of Moscow went on gathering Russian lands to increase the population and wealth under their rule. The most successful practitioner of this process was [[Ivan III of Russia|Ivan III]], the Great (1462–1505), who laid the foundations for a Russian national state. Ivan competed with his powerful northwestern rival, the [[Grand Duchy of Lithuania]], for control over some of the semi-independent [[Upper Principalities]] in the upper Dnieper and [[Oka River]] basins. | In the fifteenth century, the grand princes of Moscow went on gathering Russian lands to increase the population and wealth under their rule. The most successful practitioner of this process was [[Ivan III of Russia|Ivan III]], the Great (1462–1505), who laid the foundations for a Russian national state. Ivan competed with his powerful northwestern rival, the [[Grand Duchy of Lithuania]], for control over some of the semi-independent [[Upper Principalities]] in the upper Dnieper and [[Oka River]] basins. | ||

Through the defections of some princes, border skirmishes, and a long war with the Novgorod Republic, Ivan III was able to annex Novgorod and Tver. As a result, the [[Grand Duchy of Moscow]] tripled in size under his rule. During his conflict with Pskov, a monk named [[Filofei]] (Philotheus of Pskov) composed a letter to Ivan III, with the prophecy that the latter's kingdom will be the [[Third Rome]]. The [[Fall of Constantinople]] and the death of the last Greek Orthodox Christian emperor contributed to this new idea of Moscow as 'New Rome' and the seat of Orthodox Christianity. | Through the defections of some princes, border skirmishes, and a long war with the Novgorod Republic, Ivan III was able to annex Novgorod and Tver. As a result, the [[Grand Duchy of Moscow]] tripled in size under his rule. During his conflict with Pskov, a monk named [[Filofei]] (Philotheus of Pskov) composed a letter to Ivan III, with the prophecy that the latter's kingdom will be the [[Third Rome]]. The [[Fall of Constantinople]] and the death of the last Greek Orthodox Christian emperor contributed to this new idea of Moscow as 'New Rome' and the seat of Orthodox Christianity. | ||

| − | [[Image:LebedevK UnichNovgrodVecha.jpg|thumb|left| | + | [[Image:LebedevK UnichNovgrodVecha.jpg|thumb|left|350px|Fall of [[Novgorod Republic]] in 1478. On the right stands the last leader of the Republic, [[Marfa Boretskaya]] ]] |

A contemporary of the [[Tudor dynasty|Tudor]]s and other "new monarchs" in Western Europe, Ivan proclaimed his absolute sovereignty over all Russian princes and nobles. Refusing further tribute to the Tatars, Ivan initiated a series of attacks that opened the way for the complete defeat of the declining Golden Horde, now divided into several khanates and hordes. Ivan and his successors sought to protect the southern boundaries of their domain against attacks of the [[Khanate of Crimea|Crimean Tatars]] and other hordes. To achieve this aim, they sponsored the construction of the [[Great Abatis Belt]] and granted manors to nobles, who were obliged to serve in the military. The manor system provided a basis for an emerging horse army. | A contemporary of the [[Tudor dynasty|Tudor]]s and other "new monarchs" in Western Europe, Ivan proclaimed his absolute sovereignty over all Russian princes and nobles. Refusing further tribute to the Tatars, Ivan initiated a series of attacks that opened the way for the complete defeat of the declining Golden Horde, now divided into several khanates and hordes. Ivan and his successors sought to protect the southern boundaries of their domain against attacks of the [[Khanate of Crimea|Crimean Tatars]] and other hordes. To achieve this aim, they sponsored the construction of the [[Great Abatis Belt]] and granted manors to nobles, who were obliged to serve in the military. The manor system provided a basis for an emerging horse army. | ||

| Line 173: | Line 171: | ||

===Ivan IV, the Terrible=== | ===Ivan IV, the Terrible=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Kremlinpic4.jpg|thumb|right| | + | [[Image:Kremlinpic4.jpg|thumb|right|200px|Ivan IV, the Terrible.]] |

The development of the Tsar's autocratic powers reached a peak during the reign (1547–1584) of [[Ivan IV of Russia|Ivan IV]] ("Ivan the Terrible"). He strengthened the position of the monarch to an unprecedented degree, as he ruthlessly subordinated the nobles to his will, exiling or executing many on the slightest provocation. Nevertheless, Ivan is often seen a farsighted statesman who reformed Russia as he promulgated a new code of laws ([[Sudebnik of 1550]]), established the first Russian feudal representative body ([[Zemsky Sobor]]), curbed the influence of clergy, and introduced the local self-management in rural regions. | The development of the Tsar's autocratic powers reached a peak during the reign (1547–1584) of [[Ivan IV of Russia|Ivan IV]] ("Ivan the Terrible"). He strengthened the position of the monarch to an unprecedented degree, as he ruthlessly subordinated the nobles to his will, exiling or executing many on the slightest provocation. Nevertheless, Ivan is often seen a farsighted statesman who reformed Russia as he promulgated a new code of laws ([[Sudebnik of 1550]]), established the first Russian feudal representative body ([[Zemsky Sobor]]), curbed the influence of clergy, and introduced the local self-management in rural regions. | ||

| Line 184: | Line 182: | ||

===Time of Troubles=== | ===Time of Troubles=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Makovsky 1896.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Makovsky 1896.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Kuzma Minin appeals to the people of [[Nizhny Novgorod]] to raise a volunteer army against the Poles.]] |

The death of Ivan's childless son [[Feodor I of Russia|Feodor]] was followed by a period of civil wars and foreign intervention known as the "[[Time of Troubles]]" (1606–13). Extremely cold summer (1601-1603) wrecked crops, that led to the famine and increased the social disorganization. [[Boris Godunov]]'s reign ended in chaos, civil war combined with foreign intrusion, devastation of many cities and depopulation of the rural regions. The country rocked by internal chaos also attracted several waves of interventions by [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]]. The invaders reached Moscow and installed, first, the impostor [[False Dmitriy I]] and, later, a Polish prince [[Władysław IV Vasa]] on the Russian throne. Moscow population revolted but the riots were brutally suppressed and the city was set on fire. | The death of Ivan's childless son [[Feodor I of Russia|Feodor]] was followed by a period of civil wars and foreign intervention known as the "[[Time of Troubles]]" (1606–13). Extremely cold summer (1601-1603) wrecked crops, that led to the famine and increased the social disorganization. [[Boris Godunov]]'s reign ended in chaos, civil war combined with foreign intrusion, devastation of many cities and depopulation of the rural regions. The country rocked by internal chaos also attracted several waves of interventions by [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]]. The invaders reached Moscow and installed, first, the impostor [[False Dmitriy I]] and, later, a Polish prince [[Władysław IV Vasa]] on the Russian throne. Moscow population revolted but the riots were brutally suppressed and the city was set on fire. | ||

| Line 192: | Line 190: | ||

===Early Romanovs=== | ===Early Romanovs=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Kivchenko Election of Mikhail Romanov.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Kivchenko Election of Mikhail Romanov.jpg|thumb|300px|left|Election of 16-year-old Mikhail Romanov, the first Tsar of the Romanov dynasty.]] |

In February, 1613, with the chaos ended and the Poles expelled from Moscow, a [[Zemsky Sobor|national assembly]], composed of representatives from 50 cities and even some peasants, elected [[Michael I of Russia|Michael Romanov]], the young son of [[Patriarch Filaret]], to the throne. The [[Romanov]] dynasty ruled Russia until 1917. | In February, 1613, with the chaos ended and the Poles expelled from Moscow, a [[Zemsky Sobor|national assembly]], composed of representatives from 50 cities and even some peasants, elected [[Michael I of Russia|Michael Romanov]], the young son of [[Patriarch Filaret]], to the throne. The [[Romanov]] dynasty ruled Russia until 1917. | ||

The immediate task of the new dynasty was to restore peace. Fortunately for Moscow, its major enemies, the [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]] and [[Sweden]], were engaged in a bitter conflict with each other, which provided Russia the opportunity to make peace with Sweden in 1617 and to sign a truce with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1619. Recovery of lost territories started in the mid-seventeenth century, when the [[Chmielnicki Uprising|Khmelnitsky Uprising]] in Ukraine against the | The immediate task of the new dynasty was to restore peace. Fortunately for Moscow, its major enemies, the [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]] and [[Sweden]], were engaged in a bitter conflict with each other, which provided Russia the opportunity to make peace with Sweden in 1617 and to sign a truce with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1619. Recovery of lost territories started in the mid-seventeenth century, when the [[Chmielnicki Uprising|Khmelnitsky Uprising]] in Ukraine against the | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Image:surikov1906.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Stenka Razin Sailing in the Caspian]] | [[Image:surikov1906.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Stenka Razin Sailing in the Caspian]] | ||

| − | [[Image:Nikita Pustosviat. Dispute on the Confession of Faith.jpg|thumb|right| 300px| | + | [[Image:Nikita Pustosviat. Dispute on the Confession of Faith.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Patriarch Nikon's reform of the church service caused schism in the Russian Orthodox Church and appearance of Old Believers.]] |

Polish rule brought about the [[Treaty of Pereyaslav]] concluded between Russia and the [[Ukrainian Cossacks]]. According to the treaty, Russia granted protection to the [[Cossack Hetmanate|Cossacks state]] in the [[Left-bank Ukraine]], formerly under the Polish control. This triggered a prolonged [[Russo-Polish War (1654-1667)|Russo-Polish War]] which ended with the [[Treaty of Andrusovo]] (1667) were Poland accepted the loss of Left-bank Ukraine, [[Kiev]] and [[Smolensk]]. | Polish rule brought about the [[Treaty of Pereyaslav]] concluded between Russia and the [[Ukrainian Cossacks]]. According to the treaty, Russia granted protection to the [[Cossack Hetmanate|Cossacks state]] in the [[Left-bank Ukraine]], formerly under the Polish control. This triggered a prolonged [[Russo-Polish War (1654-1667)|Russo-Polish War]] which ended with the [[Treaty of Andrusovo]] (1667) were Poland accepted the loss of Left-bank Ukraine, [[Kiev]] and [[Smolensk]]. | ||

Rather than risk their estates in more civil war, the great nobles or ''[[boyar]]s'' cooperated with the first Romanovs, enabling them to finish the work of bureaucratic centralization. Thus, the state required service from both the old and the new nobility, primarily in the military. In return the tsars allowed the ''boyars'' to complete the process of enserfing the peasants. | Rather than risk their estates in more civil war, the great nobles or ''[[boyar]]s'' cooperated with the first Romanovs, enabling them to finish the work of bureaucratic centralization. Thus, the state required service from both the old and the new nobility, primarily in the military. In return the tsars allowed the ''boyars'' to complete the process of enserfing the peasants. | ||

| + | |||

===Peasants rebel=== | ===Peasants rebel=== | ||

In the preceding century, the state had gradually curtailed peasants' rights to move from one landlord to another. With the state now fully sanctioning [[Russian serfdom|serfdom]], runaway peasants became state fugitives, and the power of the landlords over the peasants "attached" to their land have become almost complete. Together the state and the nobles placed the overwhelming burden of taxation on the peasants, whose rate was 100 times greater in the mid-seventeenth century than it had been a century earlier. In addition, middle-class urban tradesmen and craftsmen were assessed taxes, and, like the serfs, they were forbidden to change residence. All segments of the population were subject to military levy and to special taxes. | In the preceding century, the state had gradually curtailed peasants' rights to move from one landlord to another. With the state now fully sanctioning [[Russian serfdom|serfdom]], runaway peasants became state fugitives, and the power of the landlords over the peasants "attached" to their land have become almost complete. Together the state and the nobles placed the overwhelming burden of taxation on the peasants, whose rate was 100 times greater in the mid-seventeenth century than it had been a century earlier. In addition, middle-class urban tradesmen and craftsmen were assessed taxes, and, like the serfs, they were forbidden to change residence. All segments of the population were subject to military levy and to special taxes. | ||

| Line 209: | Line 206: | ||

===Peter the Great=== | ===Peter the Great=== | ||

| − | [[Image:Surikov streltsi.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Peter I disbanded the old | + | [[Image:Surikov streltsi.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Peter I disbanded the old ''streltzi'' army. Thousands of streltzi were executed after their mutiny.]] |

[[Peter I of Russia|Peter I]], the Great (1672–1725), consolidated autocracy in Russia and played a major role in bringing his country into the European state system. From its modest beginnings in the fourteenth century principality of Moscow, Russia had become the largest state in the world by Peter's time. Three times the size of continental Europe, it spanned the Eurasian landmass from the [[Baltic Sea]] to the Pacific Ocean. Much of its expansion had taken place in the seventeenth century, culminating in the first Russian settlement of the Pacific in the mid-seventeenth century, the reconquest of Kiev, and the pacification of the Siberian tribes. However, this vast land had a population of only 14 million. Grain yields trailed behind those of agriculture in the West (that can be partly explained by the heavier climatic conditions, in particular long cold winters and short vegetative period compelling almost the entire population to farm. Only a small fraction of the population lived in the towns. Russia remained isolated from the sea trade, its internal trade communications and many manufactures were dependent on the seasonal changes. | [[Peter I of Russia|Peter I]], the Great (1672–1725), consolidated autocracy in Russia and played a major role in bringing his country into the European state system. From its modest beginnings in the fourteenth century principality of Moscow, Russia had become the largest state in the world by Peter's time. Three times the size of continental Europe, it spanned the Eurasian landmass from the [[Baltic Sea]] to the Pacific Ocean. Much of its expansion had taken place in the seventeenth century, culminating in the first Russian settlement of the Pacific in the mid-seventeenth century, the reconquest of Kiev, and the pacification of the Siberian tribes. However, this vast land had a population of only 14 million. Grain yields trailed behind those of agriculture in the West (that can be partly explained by the heavier climatic conditions, in particular long cold winters and short vegetative period compelling almost the entire population to farm. Only a small fraction of the population lived in the towns. Russia remained isolated from the sea trade, its internal trade communications and many manufactures were dependent on the seasonal changes. | ||

| Line 221: | Line 218: | ||

=== Catherine the Great=== | === Catherine the Great=== | ||

| − | [[Image:SPB Monument of Catherine II 1890-1900.jpg|thumb|left| | + | [[Image:SPB Monument of Catherine II 1890-1900.jpg|thumb|left|250px|The monument to [[Catherine II]] in [[Saint Petersberg]]]] |

Nearly forty years were to pass before a comparably ambitious and ruthless ruler appeared on the Russian throne. [[Catherine II of Russia|Catherine II]], the Great, was a German princess who married the German heir to the Russian crown. Finding him incompetent, Catherine tacitly consented to his murder. It was announced that he had died of "[[apoplexy]]", and in 1762 she became ruler. | Nearly forty years were to pass before a comparably ambitious and ruthless ruler appeared on the Russian throne. [[Catherine II of Russia|Catherine II]], the Great, was a German princess who married the German heir to the Russian crown. Finding him incompetent, Catherine tacitly consented to his murder. It was announced that he had died of "[[apoplexy]]", and in 1762 she became ruler. | ||

| Line 228: | Line 225: | ||

Catherine the Great extended Russian political control over the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth with actions including the support of the [[Targowica Confederation]], although the cost of her campaigns, on top of the oppressive social system that required lords' serfs to spend almost all of their time laboring on the lords' land, provoked a major peasant uprising in 1773, after Catherine legalized the selling of serfs separate from land. Inspired by another Cossack named [[Yemelyan Pugachev|Pugachev]], with the emphatic cry of "Hang all the landlords!" the rebels threatened to take Moscow before they were ruthlessly suppressed. Catherine had Pugachev drawn and quartered in [[Red Square]], but the specter of revolution continued to haunt her and her successors. | Catherine the Great extended Russian political control over the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth with actions including the support of the [[Targowica Confederation]], although the cost of her campaigns, on top of the oppressive social system that required lords' serfs to spend almost all of their time laboring on the lords' land, provoked a major peasant uprising in 1773, after Catherine legalized the selling of serfs separate from land. Inspired by another Cossack named [[Yemelyan Pugachev|Pugachev]], with the emphatic cry of "Hang all the landlords!" the rebels threatened to take Moscow before they were ruthlessly suppressed. Catherine had Pugachev drawn and quartered in [[Red Square]], but the specter of revolution continued to haunt her and her successors. | ||

| − | |||

[[Image:Napoleons retreat from moscow.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Napoleon's retreat from Moscow]] | [[Image:Napoleons retreat from moscow.jpg|thumb|right|300px|Napoleon's retreat from Moscow]] | ||

Catherine successfully waged war against the decaying Ottoman Empire and advanced Russia's southern boundary to the Black Sea. Then, by allying with the rulers of [[Austrian Empire|Austria]] and [[Prussia]], she incorporated the territories of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where after a century of Russian rule non-Catholic mainly Orthodox population prevailed during the [[Partitions of Poland]], pushing the Russian frontier westward into Central Europe. By the time of her death in 1796, Catherine's expansionist policy had made Russia into a major European power. This continued with [[Alexander I of Russia|Alexander I's]] wresting of [[Finland]] from the weakened kingdom of [[Sweden]] in 1809 and of [[Bessarabia]] from the Ottomans in 1812. | Catherine successfully waged war against the decaying Ottoman Empire and advanced Russia's southern boundary to the Black Sea. Then, by allying with the rulers of [[Austrian Empire|Austria]] and [[Prussia]], she incorporated the territories of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where after a century of Russian rule non-Catholic mainly Orthodox population prevailed during the [[Partitions of Poland]], pushing the Russian frontier westward into Central Europe. By the time of her death in 1796, Catherine's expansionist policy had made Russia into a major European power. This continued with [[Alexander I of Russia|Alexander I's]] wresting of [[Finland]] from the weakened kingdom of [[Sweden]] in 1809 and of [[Bessarabia]] from the Ottomans in 1812. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:suvorov crossing the alps.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Russian troops under [[Generalissimo]] Suvorov crossing the [[Alps]] in [[1799]]]] | |

[[Napoléon I of France|Napoleon]] made a major misstep when he declared war on Russia after a dispute with Tsar Alexander I and launched an [[Napoleon's invasion of Russia|invasion of Russia]] in 1812. The campaign was a catastrophe. In the bitterly cold Russian weather, thousands of French troops were ambushed and killed by peasant guerrilla fighters. As Napoleon's forces retreated, the Russian troops pursued them into Central and Western Europe and to the gates of Paris. After Russia and its allies defeated Napoleon, Alexander became known as the 'savior of Europe,' and he presided over the redrawing of the map of Europe at the [[Congress of Vienna]] (1815), which made Alexander the monarch of [[Congress Poland]]. | [[Napoléon I of France|Napoleon]] made a major misstep when he declared war on Russia after a dispute with Tsar Alexander I and launched an [[Napoleon's invasion of Russia|invasion of Russia]] in 1812. The campaign was a catastrophe. In the bitterly cold Russian weather, thousands of French troops were ambushed and killed by peasant guerrilla fighters. As Napoleon's forces retreated, the Russian troops pursued them into Central and Western Europe and to the gates of Paris. After Russia and its allies defeated Napoleon, Alexander became known as the 'savior of Europe,' and he presided over the redrawing of the map of Europe at the [[Congress of Vienna]] (1815), which made Alexander the monarch of [[Congress Poland]]. | ||

Revision as of 22:29, 21 August 2007

| Российская Федерация Rossiyskaya Federatsiya Russian Federation |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: none | ||||||

| Anthem: Hymn of the Russian Federation |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Moscow 55°45′N 37°37′E | |||||

| Official languages | Russian | |||||

| Government | Semi-presidential Federal republic | |||||

| - | President of Russia | Vladimir Putin | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Mikhail Fradkov | ||||

| Independence | from the Soviet Union | |||||

| - | Declared | June 12 1991 | ||||

| - | Finalized | December 25 1991 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 17,075,400 km² (1st) 6,592,800 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 13 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | 2006 estimate | 142,400,000 (7th) | ||||

| - | 2002 census | 145,164,000 | ||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2005 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $1.576 trillion (10th1) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $11,041 (62nd) | ||||

| Currency | Ruble (RUB) |

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC+2 to +12) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | (UTC+3 to +13) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .ru (.su reserved) | |||||

| Calling code | +7 | |||||

| 1 Rank based on April 2006 IMF data. | ||||||

Russia (Rossiya), also the Russian Federation (Росси́йская Федера́ция, Rossiyskaya Federatsiya), is a transcontinental country extending over much of northern Eurasia (Asia and Europe).

The largest country in the world by land area, Russia has the world's ninth-largest population.

Formerly the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR), a republic of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), Russia became the Russian Federation following the dissolution of the Soviet Union in December 1991.

After the Soviet era, the area, population, and industrial production of the Soviet Union (then one of the world's two Cold War superpowers, the other superpower being the United States) that were located in Russia passed on to the Russian Federation.

After the breakup of the Soviet Union, the newly-independent Russian Federation emerged as a great power and is also considered to be an energy superpower. Russia is considered the Soviet Union's successor state in diplomatic matters and is a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council.

It is also one of the five recognised nuclear weapons states and possesses the world's largest stockpile of weapons of mass destruction.

Geography

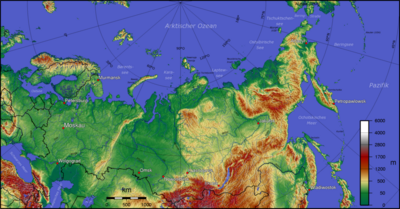

The Russian Federation stretches across much of the north of the supercontinent of Eurasia. Because of its size Russia displays both monotony and diversity. As with its topography, its climates, vegetation, and soils span vast distances.

Russia shares land borders with the following countries (counter-clockwise from northwest to southeast): Norway, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, China, Mongolia, and North Korea. It is also close to the United States (the state of Alaska), Sweden, and Japan across relatively small stretches of water (the Bering Strait, the Baltic Sea, and La Pérouse Strait, respectively).

Russia has an extensive coastline of over 37,000 kilometres (23,000 mi) along the Arctic and Pacific Oceans, as well as the Baltic, Black and Caspian seas. Some smaller bodies of water are part of the open oceans; the Barents Sea, White Sea, Kara Sea, Laptev Sea and East Siberian Sea are part of the Arctic, whereas the Bering Sea, Sea of Okhotsk and the Sea of Japan belong to the Pacific Ocean. Major islands and archipelagos include Novaya Zemlya, the Franz Josef Land, the New Siberian Islands, Wrangel Island, the Kuril Islands and Sakhalin. (See List of islands of Russia). The Diomede Islands (one controlled by Russia, the other by the United States) are just three kilometers (1.9 mi) apart, and Kunashir Island (controlled by Russia but claimed by Japan) is about twenty kilometres (12 mi) from Hokkaidō. With access to three of the world's oceans—the Atlantic, Arctic, and Pacific—Russian fishing fleets are a major contributor to the economy.

With an area of 6,592,800 square miles (17,075,400 square kilometers), Russia is by far the largest country in the world, covering almost twice the total area of the next-largest country, Canada, and has significant mineral and energy resources.

Most of the land consists broad plain with low hills west of Urals, and vast plains in Siberia. These plains are predominantly steppe to the south and heavily forested to the north, with tundra along the northern coast.

Mountain ranges are found along the southern borders, such as the Caucasus (containing Mount Elbrus, Russia's and Europe's highest point at 18,511feet (5642 meters), and the Altai, and in the eastern parts, such as the Verkhoyansk Range or the volcanoes on Kamchatka. The more central Ural Mountains, a north-south range that form the primary divide between Europe and Asia, are also notable.

The lowest point is the Caspian Sea, at 28 meters below sea level.

Russia has a largely continental climate because of its sheer size and compact configuration. Most of its land is more than 400 kilometers from the sea, and the center is 3,840 kilometers from the sea. In addition, Russia's mountain ranges, predominantly to the south and the east, block moderating temperatures from the Indian and Pacific Oceans, but European Russia and northern Siberia lack such topographic protection from the Arctic and North Atlantic Oceans. In much of the territory there are only two distinct seasons - winter and summer — spring and autumn are usually brief periods of change between extremely low and extremely high temperatures. The climates of both European and Asian Russia are continental except for the tundra and the extreme southeast. Winters vary from cool along Black Sea coast to frigid in Siberia, while summers vary from warm in the steppes to cool along Arctic coast. A small part of Black Sea coast around Sochi is considered in Russia to have subtropical climate.

Russia is a water-rich country. Russia has thousands of rivers and inland bodies of water, providing it with one of the world's largest surface-water resources. The most prominent of Russia's bodies of fresh water is Lake Baikal, the world's deepest and most capacious freshwater lake. Lake Baikal alone contains over one fifth of the world's liquid fresh surface water. Truly unique on Earth, Baikal is home to more than 1700 species of plants and animals, two thirds of which can be found nowhere else in the world.

Many rivers flow across Russia; see Rivers of Russia. Of its 100,000 rivers, Russia contains some of the world's longest. The Volga is the most famous — not only because it is the longest river in Europe but also because of its major role in Russian history. Major lakes include Lake Baikal, Lake Ladoga and Lake Onega.

Russia has a wide natural resource base including major deposits of petroleum, natural gas, coal, timber and many strategic minerals. Russia has the world's largest forest reserves, which supply lumber, pulp and paper, and raw material for woodworking industries. Formidable obstacles of climate, terrain, and distance hinder exploitation of natural resources.

Permafrost over much of Siberia is a major impediment to development. There is volcanic activity in the Kuril Islands, volcanoes and earthquakes on the Kamchatka Peninsula, and spring floods and summer/autumn forest fires throughout Siberia and parts of European Russia.

From north to south the East European Plain is clad sequentially in tundra, coniferous forest (taiga), mixed forest, broadleaf forest, grassland (steppe), and semidesert (fringing the Caspian Sea) as the changes in vegetation reflect the changes in climate. Siberia supports a similar sequence but lacks the mixed forest. Most of Siberia is taiga. (vast coniferous forest and tundra in Siberia)

air pollution from heavy industry, emissions of coal-fired electric plants, and transportation in major cities; industrial, municipal, and agricultural pollution of inland waterways and seacoasts; deforestation; soil erosion; soil contamination from improper application of agricultural chemicals; scattered areas of sometimes intense radioactive contamination; groundwater contamination from toxic waste; urban solid waste management; abandoned stocks of obsolete pesticides

According to the data of 2002 Russian Census, there are 1108 cities and towns in Russia. Moscow is the capital of Russia and the country's economic, financial, educational, and transportation centre. Located on the Moskva River in the Central Federal District, in the European part of Russia, Moscow's population constitutes about 7 percent of the total Russian population. The first Russian reference to Moscow dates from 1147. Moscow is home to many scientific and educational institutions, as well as numerous sport facilities. It possesses a complex transport system that includes the world's busiest metro system, which is famous for its architecture. Moscow also hosted the 1980 Summer Olympics.

Saint Petersburg, Russia's second major city, is located in the Northwestern Federal District of Russia on the Neva River at the east end of the Gulf of Finland on the Baltic Sea. St. Petersburg's informal name, Piter (Питер), is based on how Peter the Great was called by foreigners. The city's other names were Petrograd and Leningrad. Founded by Tsar Peter the Great in 1703 as a "window to Europe" it was capital of the Russian Empire for more than two hundred years (1712-1728, 1732-1918). St. Petersburg ceased being the capital in 1918 after the Russian Revolution of 1917.

History

Pre-Slavic inhabitants

The vast steppes of Southern Russia were home to disunited tribes, such as Proto-Indo-Europeans and Scythians. Astonishing remnants of these long-gone steppe civilizations were discovered in the course of the twentieth century in such places as Ipatovo, and Pazyryk. In the latter part of the eighth century B.C.E., Greek merchants brought classical civilization to the trade emporiums in Tanais and Phanagoria.

Between the third and sixth centuries C.E., the Bosporan Kingdom, a Hellenistic polity which succeeded the Greek colonies, was overwhelmed by successive waves of nomadic invasions, led by warlike tribes which would often move on to Europe, as was the case with Huns and Turkish Avars. A Turkic people, the Khazars, reigned the lower Volga basin steppes between the Caspian and Black Seas through the eighth century. Noted for their laws, tolerance, and cosmopolitanism, the Khazars were the main commercial link between the Baltic and the Muslim Abbasid empire centered in Baghdad. They were important allies of the Byzantine Empire, and waged a series of successful wars against the Arab Caliphates. In the 8th century, the Khazars embraced Judaism.[1]

Early East Slavs

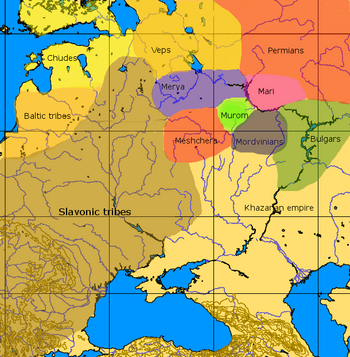

The ancestors of the Russians were the Slavic tribes, whose original home is thought by some scholars to have been the wooded areas of the Pripet Marshes. Moving into the lands vacated by the migrating Germanic tribes, the Early East Slavs gradually settled Western Russia in two waves: one moving from Kiev toward present-day Suzdal and Murom and another from Polotsk toward Novgorod and Rostov. From the seventh century onwards, the East Slavs constituted the bulk of the population in Western Russia and slowly but peacefully assimilated the native Finno-Ugric tribes, such as the Merya, the Muromians, and the Meshchera.

Kievan Rus'

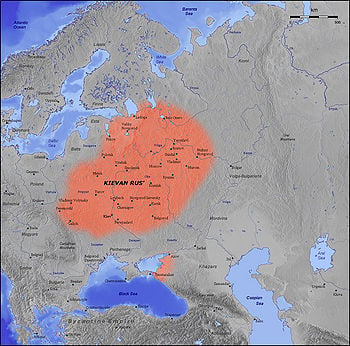

Scandinavian Norsemen, called "Vikings" in Western Europe and "Varangians" in the East, combined piracy and trade in their roamings over much of Northern Europe. In the mid-ninth century, they began to venture along the waterways from the eastern Baltic to the Black and Caspian Seas. According to the earliest chronicle of Kievan Rus', a Varangian named Rurik was elected ruler (konung or knyaz) of Novgorod in about 860, before his successors moved south and extended their authority to Kiev, which had been previously dominated by the Khazars.

Thus, the first East Slavic state, Kievan Rus', emerged in the ninth century along the Dnieper River valley. A coordinated group of princely states with a common interest in maintaining trade along the river routes, Kievan Rus' controlled the trade route for furs, wax, and slaves between Scandinavia and the Byzantine Empire along the Volkhov and Dnieper Rivers.

The name "Russia," together with the Finnish Ruotsi and Estonian Rootsi, are found by some scholars to be related to Roslagen. The etymology of Rus and its derivatives are debated, and other schools of thought connect the name with Slavic or Iranic roots.

By the end of the tenth century, the Norse minority had merged with the Slavic population, particularly among the aristocracy, which also absorbed Greek Christian influences in the course of the multiple campaigns to loot Tsargrad, or Constantinople. One such campaign claimed the life of the foremost Slavic druzhina leader, Svyatoslav I, who was renowned for having crushed the power of the Khazars on the Volga. While the fortunes of the Byzantine Empire had been ebbing, its culture was a continuous influence on the development of Russia in its formative centuries.

Kievan Rus' is important for its introduction of a Slavic variant of the Eastern Orthodox religion, dramatically deepening a synthesis of Byzantine and Slavic cultures that defined Russian culture for the next thousand years. The region adopted Christianity in 988 by the official act of public baptism of Kiev inhabitants by Prince Vladimir I. Some years later the first code of laws, Russkaya Pravda, was introduced. From the onset the Kievan princes followed the Byzantine example and kept the Church dependent on them, even for its revenues, so that the Russian Church and state were always closely linked.

By the eleventh century, particularly during the reign of Yaroslav the Wise, Kievan Rus' could boast an economy and achievements in architecture and literature superior to those that then existed in the western part of the continent. Compared with the languages of European Christendom, the Russian language was little influenced by the Greek and Latin of early Christian writings. This was due to the fact that Church Slavonic was used directly in liturgy instead.

Nomadic Turkic people Kipchaks replaced the earlier Pechenegs as a dominant force in the south steppe regions neighboring to Rus' at the end of eleventh century and founded a nomadic state in the steppes along the Black Sea (Desht-e-Kipchak). Repelling their regular attacks, especially on Kiev, which was just one day riding away from the steppe, was a heavy burden for the southern areas of Rus'. The nomadic incursions caused a massive influx of Slavic population to the safer, heavily forested regions of the North, particularly to the area known as Zalesye.

Kievan Rus' ultimately disintegrated as a state because of the armed struggles among members of the princely family that collectively possessed it. Kiev's dominance waned, to the benefit of Vladimir-Suzdal in the north-east, Novgorod in the north, and Halych-Volhynia in the south-west. Conquest by the Mongol Golden Horde in the thirteenth century was the final blow. Kiev was destroyed. Halych-Volhynia would eventually be absorbed into the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, while the Mongol-dominated Vladimir-Suzdal and independent Novgorod Republic, two regions on the periphery of Kiev, would establish the basis for the modern Russian nation.

Mongol invasion

The invading Mongols accelerated the fragmentation of the Ancient Rus'. In 1223, the disunited southern princes faced a Mongol raiding party at the Kalka River and were soundly defeated. In 1237-1238 the Mongols burnt down the city of Vladimir(February 4, 1238) and other major cities of northeast Russia, routed the Russians at the Sit' River, and then moved west into Poland and Hungary. By then they had conquered most of the Russian principalities. Only the Novgorod Republic escaped occupation and continued to flourish in the orbit of the Hanseatic League.

The impact of the Mongol invasion on the territories of Kievan Rus' was uneven. The advanced city culture was almost completely destroyed. As older centers such as Kiev and Vladimir never recovered from the devastation of the initial attack,[2] the new cities of Moscow, began to compete for hegemony in the Mongol-dominated Russia. Although a Russian army defeated the Golden Horde at Kulikovo in 1380, Tatar domination of the Russian-inhabited territories, along with demands of tribute from Russian princes, continued until about 1480.

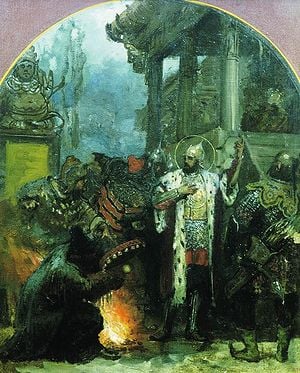

Russo-Tatar relations

After the fall of the Khazars in the tenth century, the middle Volga came to be dominated by the mercantile state of Volga Bulgaria, the last vestige of Greater Bulgaria centered at Phanagoria. In the tenth century, the Turkic population of Volga Bulgaria converted to Islam, which facilitated its trade with the Middle East and Central Asia. In the wake of the Mongol invasions of the 1230s, Volga Bulgaria was absorbed by the Golden Horde and its population evolved into the modern Chuvashes and Kazan Tatars.

The Mongols held Russia and Volga Bulgaria in sway from their western capital at Sarai, one of the largest cities of the medieval world. The princes of southern and eastern Russia had to pay tribute to the Mongols of the Golden Horde, commonly called Tatars; but in return they received charters authorizing them to act as deputies to the khans. In general, the princes were allowed considerable freedom to rule as they wished, while the Russian Orthodox Church even experienced a spiritual revival under the guidance of Metropolitan Alexis and Sergius of Radonezh.

To the Orthodox Church and most princes, the fanatical Northern Crusaders seemed a greater threat to the Russian way of life than the Mongols. In the mid-thirteenth century, Alexander Nevsky, elected prince of Novgorod, acquired heroic status as the result of major victories over the Teutonic Knights and the Swedes. Alexander obtained Mongol protection and assistance in fighting invaders from the west who, hoping to profit from the Russian collapse since the Mongol invasions, tried to grab territory and convert the Russians into Roman Catholicism.

The Mongols left their impact on the Russians in such areas as military tactics and transportation. Under Mongol occupation, Russia also developed its postal road network, census, fiscal system, and military organization. Eastern influence remained strong well until the seventeenth century, when Russian rulers made a conscious effort to Westernize their country.

The rise of Moscow

Daniil Aleksandrovich, the youngest son of Alexander Nevsky, founded the principality of Moscow (known in the western tradition as Muscovy), which eventually expelled the Tatars from Russia. Well-situated in the central river system of Russia and surrounded by protective forests and marshes, Moscow was at first only a vassal of Vladimir, but soon it absorbed its parent state. A major factor in the ascendancy of Moscow was the cooperation of its rulers with the Mongol overlords, who granted them the title of Grand Prince of Moscow and made them agents for collecting the Tatar tribute from the Russian principalities. The principality's prestige was further enhanced when it became the center of the Russian Orthodox Church. Its head, the metropolitan, fled from Kiev to Vladimir in 1299 and a few years later established the permanent headquarters of the Church in Moscow.

By the middle of the fourteenth century, the power of the Mongols was declining, and the Grand Princes felt able to openly oppose the Mongol yoke. In 1380, at Kulikovo on the Don River, the Mongols were defeated, and although this hard-fought victory did not end Tatar rule of Russia, it did bring great fame to the Grand Prince. Moscow's leadership in Russia was now firmly based and by the middle of the fourteenth century its territory had greatly expanded through purchase, war, and marriage.

Ivan III, the Great

In the fifteenth century, the grand princes of Moscow went on gathering Russian lands to increase the population and wealth under their rule. The most successful practitioner of this process was Ivan III, the Great (1462–1505), who laid the foundations for a Russian national state. Ivan competed with his powerful northwestern rival, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, for control over some of the semi-independent Upper Principalities in the upper Dnieper and Oka River basins.

Through the defections of some princes, border skirmishes, and a long war with the Novgorod Republic, Ivan III was able to annex Novgorod and Tver. As a result, the Grand Duchy of Moscow tripled in size under his rule. During his conflict with Pskov, a monk named Filofei (Philotheus of Pskov) composed a letter to Ivan III, with the prophecy that the latter's kingdom will be the Third Rome. The Fall of Constantinople and the death of the last Greek Orthodox Christian emperor contributed to this new idea of Moscow as 'New Rome' and the seat of Orthodox Christianity.

A contemporary of the Tudors and other "new monarchs" in Western Europe, Ivan proclaimed his absolute sovereignty over all Russian princes and nobles. Refusing further tribute to the Tatars, Ivan initiated a series of attacks that opened the way for the complete defeat of the declining Golden Horde, now divided into several khanates and hordes. Ivan and his successors sought to protect the southern boundaries of their domain against attacks of the Crimean Tatars and other hordes. To achieve this aim, they sponsored the construction of the Great Abatis Belt and granted manors to nobles, who were obliged to serve in the military. The manor system provided a basis for an emerging horse army.

In this way, internal consolidation accompanied outward expansion of the state. By the sixteenth century, the rulers of Moscow considered the entire Russian territory their collective property. Various semi-independent princes still claimed specific territories, but Ivan III forced the lesser princes to acknowledge the grand prince of Moscow and his descendants as unquestioned rulers with control over military, judicial, and foreign affairs. Gradually, the Russian ruler emerged as a powerful, autocratic ruler, a tsar. The first Russian ruler to officially crown himself "Tsar" was Ivan IV.

Ivan IV, the Terrible

The development of the Tsar's autocratic powers reached a peak during the reign (1547–1584) of Ivan IV ("Ivan the Terrible"). He strengthened the position of the monarch to an unprecedented degree, as he ruthlessly subordinated the nobles to his will, exiling or executing many on the slightest provocation. Nevertheless, Ivan is often seen a farsighted statesman who reformed Russia as he promulgated a new code of laws (Sudebnik of 1550), established the first Russian feudal representative body (Zemsky Sobor), curbed the influence of clergy, and introduced the local self-management in rural regions.

Although his long Livonian War for the control of the Baltic coast and the access to sea trade ultimately proved a costly failure, Ivan managed to annex the Khanates of Kazan, Astrakhan, and Siberia. These conquests complicated the migration of the aggressive nomadic hordes from Asia to Europe through Volga and Ural. Through these conquests, Russia acquired a significant Muslim Tatar population and emerged as a multiethnic and multiconfessional state. Also around this period, the mercantile Stroganov family established a firm foothold at the Urals and recruited Russian Cossacks to colonize Siberia.

In the later part of his reign, Ivan divided his realm in two. In the zone known as the oprichnina, Ivan's followers carried out a series of bloody purges of the feudal aristocracy (which he suspected of treachery after the betrayal of prince Kurbsky), culminating in the Massacre of Novgorod (1570). This combined with the military losses, epidemics, poor harvests so weakened Muscovy that the Crimean Tatars were able to sack central Russian regions and burn down Moscow (1571).

At the end of Ivan IV's reign the Polish-Lithuanian and Swedish armies carried out the powerful intervention into Russia, devastated its northern and northwest regions.

Time of Troubles

The death of Ivan's childless son Feodor was followed by a period of civil wars and foreign intervention known as the "Time of Troubles" (1606–13). Extremely cold summer (1601-1603) wrecked crops, that led to the famine and increased the social disorganization. Boris Godunov's reign ended in chaos, civil war combined with foreign intrusion, devastation of many cities and depopulation of the rural regions. The country rocked by internal chaos also attracted several waves of interventions by Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The invaders reached Moscow and installed, first, the impostor False Dmitriy I and, later, a Polish prince Władysław IV Vasa on the Russian throne. Moscow population revolted but the riots were brutally suppressed and the city was set on fire.

The crisis provoked the patriotic national uprising against the invasion and in the Autumn, 1612 the volunteer army led my the merchant Kuzma Minin and prince Dmitry Pozharsky, expelled the foreign forces from the capital.

The Russian statehood survived the "Time of Troubles" and the rule of weak or corrupt Tsars because of the strength of the government's central bureaucracy. Government functionaries continued to serve, regardless of the ruler's legitimacy or the faction controlling the throne.

Early Romanovs

In February, 1613, with the chaos ended and the Poles expelled from Moscow, a national assembly, composed of representatives from 50 cities and even some peasants, elected Michael Romanov, the young son of Patriarch Filaret, to the throne. The Romanov dynasty ruled Russia until 1917.

The immediate task of the new dynasty was to restore peace. Fortunately for Moscow, its major enemies, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Sweden, were engaged in a bitter conflict with each other, which provided Russia the opportunity to make peace with Sweden in 1617 and to sign a truce with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in 1619. Recovery of lost territories started in the mid-seventeenth century, when the Khmelnitsky Uprising in Ukraine against the

Polish rule brought about the Treaty of Pereyaslav concluded between Russia and the Ukrainian Cossacks. According to the treaty, Russia granted protection to the Cossacks state in the Left-bank Ukraine, formerly under the Polish control. This triggered a prolonged Russo-Polish War which ended with the Treaty of Andrusovo (1667) were Poland accepted the loss of Left-bank Ukraine, Kiev and Smolensk.

Rather than risk their estates in more civil war, the great nobles or boyars cooperated with the first Romanovs, enabling them to finish the work of bureaucratic centralization. Thus, the state required service from both the old and the new nobility, primarily in the military. In return the tsars allowed the boyars to complete the process of enserfing the peasants.

Peasants rebel

In the preceding century, the state had gradually curtailed peasants' rights to move from one landlord to another. With the state now fully sanctioning serfdom, runaway peasants became state fugitives, and the power of the landlords over the peasants "attached" to their land have become almost complete. Together the state and the nobles placed the overwhelming burden of taxation on the peasants, whose rate was 100 times greater in the mid-seventeenth century than it had been a century earlier. In addition, middle-class urban tradesmen and craftsmen were assessed taxes, and, like the serfs, they were forbidden to change residence. All segments of the population were subject to military levy and to special taxes.

Under such circumstances, peasant disorders were endemic; even the citizens of Moscow revolted against the Romanovs during the Salt Riot (1648), Copper Riot (1662), and the Moscow Uprising (1682). By far the greatest peasant uprising in seventeenth century Europe erupted in 1667. As the free settlers of South Russia, the Cossacks, reacted against the growing centralization of the state, serfs escaped from their landlords and joined the rebels. The Cossack leader Stenka Razin led his followers up the Volga River, inciting peasant uprisings and replacing local governments with Cossack rule. The tsar's army finally crushed his forces in 1670; a year later Stenka was captured and beheaded. Yet, less than half a century later, the strains of military expeditions produced another revolt in Astrakhan, ultimately subdued.

Peter the Great

Peter I, the Great (1672–1725), consolidated autocracy in Russia and played a major role in bringing his country into the European state system. From its modest beginnings in the fourteenth century principality of Moscow, Russia had become the largest state in the world by Peter's time. Three times the size of continental Europe, it spanned the Eurasian landmass from the Baltic Sea to the Pacific Ocean. Much of its expansion had taken place in the seventeenth century, culminating in the first Russian settlement of the Pacific in the mid-seventeenth century, the reconquest of Kiev, and the pacification of the Siberian tribes. However, this vast land had a population of only 14 million. Grain yields trailed behind those of agriculture in the West (that can be partly explained by the heavier climatic conditions, in particular long cold winters and short vegetative period compelling almost the entire population to farm. Only a small fraction of the population lived in the towns. Russia remained isolated from the sea trade, its internal trade communications and many manufactures were dependent on the seasonal changes.

Peter's first military efforts were directed against the Ottoman Turks.His aim was to establish a Russian foothold on the Black Sea by taking the town of Azov. His attention then turned to the north. Peter still lacked a secure northern seaport except at Archangel on the White Sea, whose harbor was frozen nine months a year. Access to the Baltic was blocked by Sweden, whose territory enclosed it on three sides. Peter's ambitions for a "window to the sea" led him in 1699 to make a secret alliance with the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Denmark against Sweden resulting in the Great Northern War. The war ended in 1721 when an exhausted Sweden sued for peace with Russia. Peter acquired four provinces situated south and east of the Gulf of Finland, thus securing his coveted access to the sea. There, in 1703, he had already founded the city that was to become Russia's new capital, St. Petersburg, as a "window opened upon Europe" to replace Moscow, long Russia's cultural center. Russian intervention in the Commonwealth marked, with the Silent Sejm, beginning of 200-year domination of that region by the Russian Empire. In celebration of his conquests, Peter assumed the title of emperor as well as tsar, and Muscovite Russia officially became the Russian Empire in 1721.

Peter reorganized his government on the latest Western models, molding Russia into an absolutist state. He replaced the old boyar Duma (council of nobles) with a nine-member senate, in effect a supreme council of state. The countryside was also divided into new provinces and districts. Peter told the senate that its mission was to collect tax revenues. In turn tax revenues tripled over the course of his reign. As part of the government reform, the Orthodox Church was partially incorporated into the country's administrative structure, in effect making it a tool of the state. Peter abolished the patriarchate and replaced it with a collective body, the Holy Synod, led by a lay government official. Meanwhile, all vestiges of local self-government were removed, and Peter continued and intensified his predecessors' requirement of state service for all nobles.

Peter died in 1725, leaving an unsettled succession and an exhausted realm. His reign raised questions about Russia's backwardness, its relationship to the West, the appropriateness of reform from above, and other fundamental problems that have confronted many of Russia's subsequent rulers. Nevertheless, he had laid the foundations of a modern state in Russia.

Catherine the Great

Nearly forty years were to pass before a comparably ambitious and ruthless ruler appeared on the Russian throne. Catherine II, the Great, was a German princess who married the German heir to the Russian crown. Finding him incompetent, Catherine tacitly consented to his murder. It was announced that he had died of "apoplexy", and in 1762 she became ruler.

Catherine contributed to the resurgence of the Russian nobility that began after the death of Peter the Great. Mandatory state service had been abolished, and Catherine delighted the nobles further by turning over most government functions in the provinces to them.

Catherine the Great extended Russian political control over the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth with actions including the support of the Targowica Confederation, although the cost of her campaigns, on top of the oppressive social system that required lords' serfs to spend almost all of their time laboring on the lords' land, provoked a major peasant uprising in 1773, after Catherine legalized the selling of serfs separate from land. Inspired by another Cossack named Pugachev, with the emphatic cry of "Hang all the landlords!" the rebels threatened to take Moscow before they were ruthlessly suppressed. Catherine had Pugachev drawn and quartered in Red Square, but the specter of revolution continued to haunt her and her successors.

Catherine successfully waged war against the decaying Ottoman Empire and advanced Russia's southern boundary to the Black Sea. Then, by allying with the rulers of Austria and Prussia, she incorporated the territories of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where after a century of Russian rule non-Catholic mainly Orthodox population prevailed during the Partitions of Poland, pushing the Russian frontier westward into Central Europe. By the time of her death in 1796, Catherine's expansionist policy had made Russia into a major European power. This continued with Alexander I's wresting of Finland from the weakened kingdom of Sweden in 1809 and of Bessarabia from the Ottomans in 1812.

Napoleon made a major misstep when he declared war on Russia after a dispute with Tsar Alexander I and launched an invasion of Russia in 1812. The campaign was a catastrophe. In the bitterly cold Russian weather, thousands of French troops were ambushed and killed by peasant guerrilla fighters. As Napoleon's forces retreated, the Russian troops pursued them into Central and Western Europe and to the gates of Paris. After Russia and its allies defeated Napoleon, Alexander became known as the 'savior of Europe,' and he presided over the redrawing of the map of Europe at the Congress of Vienna (1815), which made Alexander the monarch of Congress Poland.

Although the Russian Empire would play a leading political role in the next century, secured by its defeat of Napoleonic France, its retention of serfdom precluded economic progress of any significant degree. As West European economic growth accelerated during the Industrial Revolution, sea trade and exploitation of colonies which had begun in the second half of the eighteenth century, Russia began to lag ever farther behind, creating new problems for the empire as a great power.

xxxx The perseverance of Russian serfdom and the conservative policies of Nicholas I of Russia impeded the development of Imperial Russia in the mid-nineteenth century. As a result, the country was defeated in the Crimean War, 1853–1856, by an alliance of major European powers, including Britain, France, Ottoman Empire, and Piedmont-Sardinia. Nicholas's successor Alexander II (1855–1881) was forced to undertake a series of comprehensive reforms and issued a decree abolishing serfdom in 1861. The Great Reforms of Alexander's reign spurred increasingly rapid capitalist development and Sergei Witte's attempts at industrialisation. The Slavophile mood was on the rise, spearheaded by Russia's victory in the Russo-Turkish War, which forced the Ottoman Empire to recognise the independence of Romania, Serbia and Montenegro and autonomy of Bulgaria.

The failure of agrarian reforms and suppression of the growing liberal intelligentsia were continuing problems however, and on the eve of World War I, the position of Tsar Nicholas II and his dynasty appeared precarious. The Russian government did not want war in 1914 but felt that the only alternative was acceptance of German domination of Europe.[3] Upper- and middle-class Russians rallied around the regime’s war effort.[3] Peasants and workers were much less enthusiastic.[3] Germany was Europe’s leading military and industrial power, and Austria and the Ottoman Empire were its allies in the war.[3] Consequently, Russia was forced to fight on three fronts and was isolated from its French and British war partners.[3] Under these circumstances the Russian war effort was impressive.[3] Having won a number of major battles in 1916, the army was far from defeated when the Russian Revolution of 1917 broke out in February.[3] The home front collapsed under the strains of war, partly for economic reasons but primarily because the already existing public distrust of the regime was deepened by tales of inefficiency, corruption, and even treason in high places.[3] Many of these tales were nonsense or grossly exaggerated, such as the belief that a semiliterate mystic, Grigory Rasputin, had great political influence within the government.[3] What mattered, however, was that the rumors were believed.[3] At the close of the Russian Revolution of 1917, a Marxist political faction called the Bolsheviks seized power in Petrograd and Moscow under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin. The Bolsheviks changed their name to the Communist Party. A bloody civil war ensued, pitting the Bolsheviks' Red Army against a loose confederation of anti-socialist monarchist and bourgeois forces known as the White Army. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, a peace treaty signed by the Central Powers with Soviet Russia, concluded hostilities between those countries in World War I. Russia lost the Ukraine, its Polish and Baltic territories, and Finland by signing the treaty, which was later annulled by the Armistice. Following the defeat of the Central Powers and the Armistice treaty, these states became independent, but were later incorporated into the Soviet Union, which effectively covered the same territory that Russia did before the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. The Red Army triumphed in the Civil War, and the Soviet Union was formed in 1922.

Soviet Russia

After a failed Bolshevik rising in July 1917, Lenin fled to Finland for safety. Here he wrote "State and Revolution",[4] which called for a new form of government based on workers' councils, or soviets elected and revocable at all moments by the workers. He returned to Petrograd in October, inspiring the October Revolution with the slogan "All Power to the Soviets!". Lenin directed the overthrow of the Provisional Government from the Smolny Institute from the 6th to the 8th of November 1917. The storming and capitulation of the Winter Palace on the night of the 7th to 8th of November marked the beginning of Soviet rule. On November 8, 1917, Lenin was elected as the Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars by the Russian Congress of Soviets. Lenin emphasised the importance of bringing electricity to all corners of Russia and modernising industry and agriculture. He was very concerned about creating a free universal health care system for all, the rights of women, and teaching all Russian people to read and write.[5] On December 301922, the Russian SFSR together with three other Soviet republics formed the Soviet Union.[6]

The Soviet Union was meant to be a trans-national worker's state free from nationalism.[citation needed] The concept of Russia as a separate national entity was therefore not emphasised in the early Soviet Union.[citation needed] However, people and leaders around the world often referred to the Soviet Union as "Russia" and its people as "Russians". The Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic dominated the Soviet Union for its entire 74-year history.[7] The Russian Federation was by far the largest of the republics; Moscow, its capital, was also the capital of the Soviet Union.[7] Although Russian institutions and cities certainly remained dominant, non-Russians participated in the new government at all levels. After Lenin's death in 1924, a brief power struggle ensued, during which a top communist official, a Georgian named Joseph Stalin, gradually eroded the various checks and balances which had been designed into the Soviet political system and assumed dictatorial power by the end of the decade.[6]

1927-1953

Stalin forced rapid industrialisation of the largely rural country and collectivisation of its agriculture. In 1928, Stalin introduced his First Five Year Plan for modernising the Soviet economy.[8] Most economic output was immediately diverted to establishing heavy industry. Civilian industry was modernised and many heavy weapon factories were established. The plan worked, in some sense, as the Soviet Union successfully transformed from an agrarian economy to a major industrial powerhouse in an unbelievably short span of time, but widespread misery and famine ensued for many millions of people as a result of the severe economic upheaval.

Almost all Old Bolsheviks from the time of the Revolution, including Leon Trotsky, were killed or exiled. At the end of 1930s, Stalin launched the Great Purges, a massive series of political repressions. Millions of people whom Stalin and local authorities suspected of being a threat to their power were executed or exiled to Gulag labor camps in remote areas of Siberia or Central Asia. A number of ethnic groups in Russia and other republics were also forcibly resettled during Stalin's rule.

The defensive war of the Soviet Union against Nazi Germany, part of the World War II known in the Soviet Union and Russia as the Great Patriotic War, started with the German invasion of the Soviet Union on June 221941. It was the largest theatre of war in history and was notorious for its unprecedented ferocity, destruction, and immense loss of life. The fighting involved millions of German and Soviet troops along a broad front. It was by far the deadliest single theatre of war in World War II, with over 5.5 million deaths on the Axis Forces; Soviet military deaths were about 8.6 million (out of which 2.8 - 3.3 million Soviet prisoners of war (of 5.5 million) died in German captivity),[9][10][11] and civilian deaths were about 14 to 18 million. The Eastern Front contained more combat than all the other European fronts combined; the German army suffered 80% to 93% of all casualties there.[12][13] The fate of the Third Reich was decided at Stalingrad and sealed at Kursk. The German army had considerable success in the early stages of the campaign, but they suffered defeat when they reached the outskirts of Moscow. The Red Army then stopped the Nazi offensive at the Battle of Stalingrad in the winter of 1942-43, which became the decisive turning point for Germany's fortunes in the war. The Soviets drove through Eastern Europe and captured Berlin before Germany surrendered in 1945. During the war, the Soviet Union lost around 27 million citizens [14][15] (including up to 18 million civilians), about half of all World War II casualties.

Although ravaged by the war, the Soviet Union emerged from the conflict as an acknowledged superpower. The Red Army occupied Eastern Europe after the war, including the eastern half of Germany. Stalin installed loyal communist governments in these satellite states. During the immediate postwar period, the Soviet Union first rebuilt and then expanded its economy, with control always exerted exclusively from Moscow. The Soviets extracted heavy war reparations from the areas of Germany under their control, mostly in the form of machinery and industrial equipment. The Soviet Union consolidated its hold on Eastern Europe (see Eastern bloc) and entered a long struggle with the United States and Western Europe on economic, political, and ideological dominance over the Third World. The ensuing struggle became known as the Cold War, which turned the Soviet Union's wartime allies, Britain and the United States, into its foes.

1953-1985

Under Khrushchev, the Soviet Union launched the world's first artificial satellite, Sputnik 1, and the Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin became the first human to orbit the Earth aboard the first manned spacecraft, Vostok 1. The space race produced rapid advances in rocketry, material science, computers, and many other areas. Khrushchev's reforms in agriculture and administration, however, were generally unproductive. Foreign policy toward China and the United States suffered reverses, notably the Cuban Missile Crisis, when Khrushchev began installing nuclear missiles in Cuba (after the United States installed Jupiter missiles in Turkey, which nearly provoked a war with the Soviet Union). Following the ousting of Khrushchev, another period of rule by collective leadership ensued until Leonid Brezhnev established himself in the early 1970s as the pre-eminent figure in Soviet politics. Brezhnev is frequently derided by historians for stagnating the development of the Soviet Union (see "Brezhnev stagnation"). Others have acknowledged that despite its inertia and repression (though very mild relative to the Stalin years), the Brezhnev era did offer a relative prosperity to a populace and leadership battered by decades of war, famine, collectivisation and crash industrialisation, deadly political crises, arbitrary mass murder and arrest, and the volatility of the Khrushchev years. In 1979 the troubled nine-year Soviet war in Afghanistan began.

1985-1991

Following the short rules of Yury Andropov and Konstantin Chernenko, in 1985, the reform-minded[16] Mikhail Gorbachev came to power. He introduced the landmark policies of glasnost (openness) and perestroika (restructuring), in an attempt to modernise Soviet communism. Glasnost meant that the harsh restrictions on free speech that had characterised most of the Soviet Union's existence were alleviated, and open political discourse and criticism of the government became possible again. Perestroika meant sweeping economic reforms designed to decentralise the planning of the Soviet economy. However, the Stalinist system was probably beyond repair, and the Gorbachev reforms started in motion forces of change that demonstrated that meaningful reform would eventually threaten Communist Party hegemony. His initiatives also provoked strong resentment amongst conservative elements of the government, and in August of 1991 an unsuccessful military coup that attempted to remove Gorbachev from power instead led to the collapse of the Soviet Union. Boris Yeltsin came to power and declared the end of exclusive Communist rule. The USSR splintered into fifteen independent republics, and was officially dissolved in December of 1991. Prior to the dissolution of the Soviet Union, Boris Yeltsin had been elected President of Russia in June 1991 in the first direct presidential election in Russian history. In October 1991, as Russia was on the verge of independence, Yeltsin announced that Russia would proceed with radical market-oriented reform along the lines of "shock therapy".[17]

Post-Soviet Russia

After the disintegration of the USSR, the Russian economy went through a crisis.[18] Russia took up the responsibility for settling the USSR's external debts, even though its population made up just half of the population of the USSR at the time of its dissolution.[19] The largest state enterprises (petroleum, metallurgy, and the like) were controversially privatised by President Boris Yeltsin to insiders[20] (who became billionaires virtually overnight) for far less than they were worth, while the majority of the population plunged into poverty.[17] Corruption has run rampant,[21] and the Yeltsin government has been accused of conspiring with insiders to loot countless billions in cash and assets from the State[22] (for example, Yeltsin's son-in-law became the CEO of Aeroflot, Russia's largest airline).

The 1990s were plagued by armed ethnic conflicts in the North Caucasus.[17] Such conflicts took a form of separatist Islamist insurrections against federal power (most notably in Chechnya), or of ethnic/clan conflicts between local groups (e.g., in North Ossetia-Alania between Ossetians and Ingushs, or between different clans in Chechnya).[17] Since the Chechen separatists declared independence in the early 1990s, an intermittent guerrilla war (First Chechen War, Second Chechen War) has been fought between disparate Chechen groups and the Russian military.[17] Russia has severely disabled the Chechen rebel movement, although sporadic violence still occurs throughout the North Caucasus.[24]

After Yeltsin's presidency in the 1990s, the recently appointed Prime Minister (who was also head of the FSB from July 1998 through August 1999) Vladimir Putin was elected in 2000. High oil prices and growing internal demand boosted Russian economic growth, stimulating significant economic expansion abroad and helping to finance increased military spending.[17] Putin's presidency has shown improvements in the Russian standard of living, as opposed to the 1990s.[17][25] Under Putin, the economy developed significantly and currently Russia enjoys a state of rapid economical growth, averaging 6.7% annual GDP growth for the past 8 straight years.[24]

Government and politics

The politics of the Russian Federation take place in a framework of a federal presidential republic.According to the Constitution of Russia, the president is head of state, and of a pluriform multi-party system with executive power exercised by the government, headed by the prime minister, who is appointed by the president by the parliament's approbation. Legislative power is vested in the two chambers of the federal assembly, while the president and the government issue numerous legally binding by-laws. Although Russia has traditionally been ruled by absolute monarchs and dictators, in 2007 it had a democratic system of government.

Structure

For the executive, the president is elected by popular vote for a four-year term and is eligible for a second term. An election was last held in March 2004. Vladimir Putin has been acting president since December 1999, and president since May 2000. The president appoints a cabinet comprising the premier and his deputies, ministers, and selected other individuals.