Montenegro

| –¶—Ä–Ĺ–į –ď–ĺ—Ä–į Crna Gora Montenegro |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem:¬†Oj, svijetla majska zoro Montenegrin: Oj, svijetla majska zoro (Montenegrin Cyrillic: –ě—ė, —Ā–≤–ł—ė–Ķ—ā–Ľ–į –ľ–į—ė—Ā–ļ–į –∑–ĺ—Ä–ĺ) "Oh, Bright Dawn of May" |

||||||

| |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | 42¬į47‚Ä≤N 19¬į28‚Ä≤E | |||||

| Official languages | Montenegrin | |||||

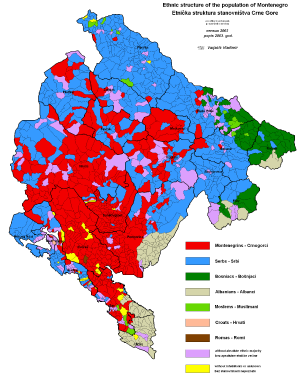

| Ethnic groups (2011) | 44.98% Montenegrins, 28.73% Serbs, 8.65% Bosniaks, 4.91% Albanians, 3.31% Muslims, 0.97% Croats, 8.45% others and unspecified[1] |

|||||

| Demonym | Montenegrin | |||||

| Government | Parliamentary republic | |||||

| ¬†-¬† | President | Jakov Milatovińá | ||||

| ¬†-¬† | Prime Minister | Milojko Spajińá | ||||

| ¬†-¬† | Speaker | Andrija Mandińá | ||||

| Legislature | Parliament | |||||

| Establishment | ||||||

|  -  | Independence of Duklja from Byzantine Empire | 1042  | ||||

|  -  | Independence of Zeta from Serbian Empire | 1360 (de jure) 1356 (de facto)  |

||||

|  -  | Independence from Serbia and Montenegro | 2006  | ||||

| Area | ||||||

|  -  | Total | 13,812 km² (161st) 5,019 sq mi  |

||||

|  -  | Water (%) | 1.5 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

|  -  | 2023 census | |||||

|  -  | Density | 43.6/km² (133rd) 124/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate | |||||

|  -  | Total | |||||

|  -  | Per capita | |||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate | |||||

|  -  | Total | |||||

|  -  | Per capita | |||||

| Gini (2018) | 36.8[3]  | |||||

| Currency | Euro (‚ā¨)2 (EUR) |

|||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

|  -  | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Internet TLD | .me | |||||

| Calling code | [[+382]] | |||||

| 1 The traditional old capital of Montenegro is Cetinje. 2 Adopted unilaterally; Montenegro is not a formal member of the Eurozone. |

||||||

Montenegro, meaning "black mountain" is a small, mountainous state in south-west Balkans, bordering Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, Albania and the Adriatic Sea.

Periodically independent since the late Middle Ages, and an internationally recognized country from 1878 until 1918, Montenegro was later a part of various incarnations of Yugoslavia and the state union of Serbia and Montenegro.

Based on the results of a referendum, Montenegro declared independence on June 3, 2006, and on June 28, 2006, it became the 192nd member state of the United Nations.

Montenegro avoided the ethnic strife that tore other areas of the Balkans apart in the 1990s, arguably because of greater ethnic, religious, and linguistic homogeneity, and because Montenegro remained united with Serbia during the 1990s wars. Serbs regard Montenegrins as ‚ÄúMountain Serbs,‚ÄĚ while Montenegrins see themselves as Serb in origin. Both are Orthodox Christians.

Geography

With a land area 5019 square miles (13,812 square kilometers), Montenegro is slightly smaller than the U.S. state of Connecticut. Montenegro ranges from high peaks along its borders with Serbia and Albania, a segment of the Karst of the western Balkan Peninsula, to a narrow coastal plain that is one to four miles wide. The plain stops abruptly in the north, where Mount Lovńáen and Mount Orjen plunge abruptly into the inlet of the Bay of Kotor.

Montenegro's large Karst region lies at elevations of 3281 feet (1000 meters) above sea level. Some parts rise to 6560 feet (2000 meters), such as Mount Orjen at 6214 feet (1894 meters), the highest massif among the coastal limestone ranges. The Zeta River valley, at an elevation of 1640 feet (500 meters), is the lowest segment.

The mountains of Montenegro include some of the most rugged terrain in Europe. They average more than 6560 feet (2000 meters) in elevation. One of the country's notable peaks is Bobotov Kuk in the Durmitor mountains, which reaches a height of 8274 feet (2522 meters). The Montenegrin mountain ranges were among the most ice-eroded parts of the Balkan Peninsula during the last glacial period. Natural resources include bauxite and hydroelectricity.

Lower areas have a Mediterranean climate, with dry summers and mild, rainy winters. Temperature varies with elevation. Podgorica, near sea level, has the warmest July (summer) temperatures, averaging 81¬įF (27¬įC). Cetinje, in the Karst region at 2200 feet (670m), has an average temperature that is 10¬įF (5¬įC) lower. Average January (winter) temperatures at Bar on the southern coast are 46¬įF (8¬įC). Annual precipitation at Crkvice, in the Karst, is nearly 200 inches (5100mm), during the cold part of the year. Snow cover is rare along the Montenegrin coast, increasing to 120 days in the higher mountains.

Run-off in the north enters the Lim and Tara rivers, which flow into the Drina River, which forms the border between Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia. In the south, streams flow toward the Adriatic Sea. Drainage of the karst region travels in underground channels. Lake Scutari (Skadarsko Jezero), at 25 miles (40km) long and 10 miles (16km) wide, is the country's largest lake and extends into northern Albania. The mountains are noted for numerous smaller lakes.

One-third of Montenegro, mainly the high mountains, remains covered with broad-leaved forest. The southern Karst zone, lacking soils, remained forested through classical times, with oaks and cypresses predominating. Removal of forests for domestic fuel and construction led to soil erosion and ultimately, to regeneration in Mediterranean scrub known as maquis.

Sparsely populated Montenegro has numerous mammals, including bears, deer, martens, and wild pigs, as well as predatory wild animals, including wolves, foxes, and wildcats, along with a rich variety of birds, reptiles, and fish.

Destructive earthquakes are the main natural hazard. Environmental issues relate to the pollution of coastal waters from sewage outlets, especially in tourist-related areas such as Kotor.

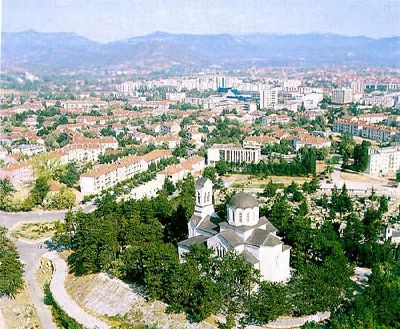

Its capital and largest city is Podgorica. The location at the confluence of the Ribnica and Morańća rivers, on the meeting point of fertile Zeta plain and Bjelopavlińái Valley, has made the city an attractive location for settlement. The city is situated close to winter ski centers in the north and seaside resorts on Adriatic Sea. Besides being an administrative center, Podgorica is its economic, cultural and educational focal point.

Cetinje is designated as Prijestonica. the old royal capital or seat of the throne. Other cities and towns include NikŇ°ińá, Pljevlja, Bijelo Polje, Herceg Novi, including Igalo), and Berane.

History

The lands that later became Montenegro were inhabited in the Paleolithic Age (Stone Age) by cave dwellers over 100,000 years ago. The population increased in the Neolithic age (c. 8000 B.C.E.), marked by the rise of farming. People began to abandon caverns and settle in open areas. The remains of a number of such settlements have been discovered in Montenegro. Stockbreeding people, who came from the east around the mid-3000s B.C.E. to the early 2000s B.C.E., mixed with the indigenous peoples and thus created the Indo-European peoples of the Balkans, believed to be the ancient Pelasgians mentioned frequently by ancient writers Homer, Herodotus, and Thucydides.

Illyria

The Illyrians were Indo-European tribesmen who appeared in the western portion of the Balkan Peninsula about 1000 B.C.E., a period coinciding with the beginning of the Iron Age. The Illyrians occupied lands extending from the Danube, Sava, and Morava rivers to the Adriatic Sea and the Sar Mountains.

Corinthian Greek settlers from Corfu established ports on the coast. The Illyrians resisted Greek settlement, attacked coastal cities, and threatened Greek trading ships in the Adriatic Sea. The Illyrian king, Bardyllis turned Illyria into a formidable local power in the fourth century B.C.E., with its capital at Skadar (Albania).

In 358 B.C.E., Macedonia's Philip II, the father of Alexander the Great, defeated the Illyrians and assumed control of their territory as far as Lake Ohrid. Alexander himself routed the forces of the Illyrian chieftain Cleitus in 335 B.C.E., and Illyrian tribal leaders and soldiers accompanied Alexander on his conquest of Persia.

Roman rule

Between 229 and 219 B.C.E., Rome overran the Illyrian settlements in the Neretva river valley and suppressed the piracy that had made the Adriatic unsafe. The Romans defeated the last Illyrian king Gentius at Scodra in 168 B.C.E., captured him, and brought him to Rome in 165 B.C.E. Rome finally subjugated recalcitrant Illyrian tribes in the western Balkans during the reign of Emperor Tiberius in 9 C.E., and annexing them to the Roman province of Illyricum.

Parts of present-day Montenegro, Serbia, and Albania were known as the ancient Roman province of Praevalitana. It was formed during the reign of emperor Diocletian (284-305) from southeastern corner of the province of Dalmatia. "Doclea," the name of the region during the early period of the Roman Empire, was named after an early Illyrian tribe - the Docleatae. The city of Doclea (or Dioclea) was located at present-day Podgorica (and was throughout the Middle Ages known as Ribnica).

For about four centuries, Roman rule ended fighting among local tribes, established numerous military camps and colonies, latinized the coastal cities, and oversaw the construction of aqueducts and roads, including the extension of the Via Egnatia, an old Illyrian road and later a famous military highway and trade route that led from Durr√ęs through the Shkumbin River valley to Macedonia and Byzantium.

The division of the Roman Empire between Roman and Byzantine rule ‚Äď and subsequently between the Latin and Greek churches ‚Äď was marked by a line that ran northward from Skadar through modern Montenegro, making this region a perpetual marginal zone between the economic, cultural, and political worlds of the Mediterranean peoples and the Slavs.

As Roman power declined in the fifth century, this part of the Adriatic coast suffered from intermittent ravages by various semi-nomadic invaders, especially the Goths in the late fifth century, and the Avars during the sixth century.

Slavic invasion

Byzantine Emperor Heraclius (575‚Äď641) commissioned Slavic tribal groups to drive Avars and Bulgars toward the east. Slavs settled the Balkans, and tribes known as the Serbs settled inland of the Dalmatian coast in an area extending from eastern Herzegovina, across northern Montenegro, and into southeastern Serbia. A chieftain named Vlastimir, founder of the House of Vlastimirovińá, created the Serb state around 850, centered on an area in southern Serbia known as RaŇ°ka. That kingdom accepted the supremacy of Constantinople, the start of an on-going link between the Serbian people and Orthodox Christianity. Byzantine emperor Michael III (840-867) sent brothers Cyril and Methodius to evangelize the Slavs. Slavic people were organized along tribal lines, each headed by a zupan (chieftain). From the time of the arrival of the Slavs to the tenth century, the zupans entered into unstable alliances with larger states, notably Bulgaria, Venice, and Byzantium.

Duklja

In the first half of the seventh century, Slavs formed the Principality of Doclea. The population was a mixture of Slavic pagans and Latinized Romans along the Byzantine enclaves of the coastline, with some Illyrian descendants. Around 753, the population was described as Red Croats. Although independent, they attracted Serbian attention in the ninth century. The tribes organized themselves into a semi-independent dukedom of Duklja(Doclea) by the tenth century.

Prince ńĆaslav Klominirovińá of the Serbian House of Vlastimirovińá dynasty extended his influence over Duklja in the tenth century. After the fall of the Serbian Realm in 960, the people of Duklja faced a renewed Byzantine occupation through to the eleventh century. The local ruler, Jovan Vladimir, whose cult remains in the Orthodox Christian tradition in Montenegro, struggled to retain independence while he ruled Duklja from 990 to 1016, when he was assassinated. His cousin, Stefan Vojislav, who ruled Duklja from 1034 to 1050, started an uprising against the Byzantine domination and gained a victory against Byzantine forces in Tudjemili (Bar) in 1042, which ended Byzantine influence over Duklja.

In the 1054 Great Schism, the people of Duklja sided with the Catholic Church. The city of Bar became a Bishopric in 1067. In 1077, Pope Gregory VII recognized Duklja as an independent state, acknowledging its King Mihailo (Michael, of the Vojisavljevińá dynasty) as King of Duklja. Later on Mihailo sent his troops, led by his son Bodin, in 1072 to assist the uprising of Slavs in Macedonia.

Duklja devastated

When Stefan Nemanja (1109-99) assumed the throne of RaŇ°ka in 1168, he launched an offensive against Duklja. He devastated coastal towns which subsequently never recovered, burned churches and manuscripts, persecuted the heretical Bogomils, expelled the Greeks from the area, and forced the population to convert to Orthodox Christianity. Duklja fell to the Serbs in 1189.

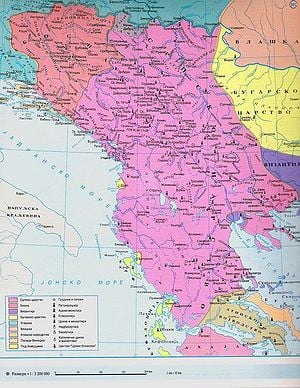

In 1196, Nemanja abdicated, handing the crown to his son Stefan, who in 1217 was named by Pope Honorius III the ‚ÄúKing of Serbia, Dalmatia, and Bosnia.‚ÄĚ The Nemanjic dynasty ruled for 200 years, helped by the collapse of the Byzantine Empire under the impact of the Fourth Crusade (1204). During the reign of Emperor Dusan (1331-1355), the state incorporated Thessaly, Epirus, Macedonia, all of modern Albania and Montenegro, a substantial part of eastern Bosnia, and modern Serbia as far north as the Danube. On the death of Stefan DuŇ°an in 1355, the Nemanjic empire was divided among Prince Lazar Hrebeljanovic (1329-1389) of Serbia, the short-lived Bosnian state of Tvrtko I (reigned 1353‚Äď1391), and a semi-independent chiefdom of Zeta under the house of BalŇ°a, with its capital at Skadar (Albania).

Ottoman invasion

In 1389, the forces of Ottoman Sultan Murad I defeated Prince Lazar Hrebeljanovic's Serbs at the Battle of Kosovo. The northern Serbian territories were conquered in 1459 following the siege of the "temporary" capital Smederevo. Bosnia fell a few years after Smederevo, and Herzegovina in 1482. Most of Serbia was under Ottoman occupation between 1459 and 1804, despite three Austrian invasions and numerous rebellions (such as the Banat Uprising). The Ottoman period was a defining one in the history of the country‚ÄĒSlavic, Byzantine, Arabic and Turkish cultures combined.

The principality of Zeta

Zeta, named after the Zeta River, was first noted as a vassalaged part of Rascia, ruled by heirs to the Serbian throne from the Nemanjińá dynasty. Zeta gained independence from Rascia in 1356, under the leadership of BalŇ°a I, and the House of BalŇ°ińá ruled from the 1360s to 1421. Serb resistance moved to Zabljak (south of Podgorica), where a chieftain named Stefan Crnojevic (1426-1465) set up his capital.

His successor Ivan I Crnojevic, (who ruled from 1465-1490), sought to maintain good relations with the Venetians and Turks. That way, he found favor with those two powerful countries for his successor. Ivan's son Djuradj, who ruled the Principality of Zeta between 1490 and 1496, built a monastery at Cetinje, founding there a bishopric, and imported from Venice a printing press that produced after 1493 some of the earliest books in the Cyrillic script. He was well known for his great education, and his knowledge of astronomy, geometry, and other sciences. During the reign of Djuradj, Zeta became better known as Montenegro, which means Black Mountain in Italian. It was succeeded by theocratic Montenegro and Ottoman-ruled Montenegro.

Venetians control coast

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire (476), the romanized Illyrians of the southern coast of Dalmatia survived the barbarian invasions of the Avars and were only nominally under the influence of the Slavs. These Romanized Illyrians started to develop their own neo-Latin language, called Dalmatian language, around their small coastal villages that were growing with maritime commerce.

The Republic of Venice dominated the coasts of today's Montenegro from 1420 to 1797. In those four centuries the area around the Cattaro (Kotor) became part of the Venetian albania-montenegro, called in those centuries Albania veneta. When the Turks started to conquer the Balkans in the fifteenth century, many Christian Slavs and Albanians took refuge inside the Venetian Dalmatia. Bar and Ulcinj were conquered by the Ottomans in the 1570s. The Venetian language was the lingua franca of the Adriatic coast of Montenegro during those centuries. In the area of Bay of Kotor there were Venetian speaking populations until the first half of the twentieth century.

Theocratic Montenegro

In 1516, the secular prince ńźurańĎ V Crnojevińá abdicated in favor of the Archbishop Vavil, who then formed Montenegro into a theocratic state under the rule of the prince-bishop (vladika) of Cetinje. The position of the vladika brought stability to Montenegro's leadership, since the link between church and state elevated it in the eyes of the peasantry, it institutionalized a form of succession, and avoided compromising alliances with the Ottomans. At that time, Montenegro was at war with the Ottoman Empire. Cetinje was captured in 1623, in 1687, and in 1712.

Ottoman province of Montenegro

The Ottoman Province of Montenegro was created in 1514 from the remains of the Principality of Zeta that belonged to the Province of Scutari. The first known governor of the province was Skenderbeg Crnojevińá, son of Ivan Crnojevińá, who governed from 1514-1528. Although the Ottoman Empire controlled the lands to the south and east from the fifteenth century, they were unable to subdue Montenegro completely because of stubborn resistance by the population, the inhospitable terrain, and use of diplomatic ties with Venice. The province disappeared when the Montenegrins expelled the Ottomans in the Great Turkish War of 1683-1699 (also known as War of the Holy League).

Principality to kingdom

The position of vladika was transmitted from 1697 by the Petrovińá-NjegoŇ° family of the RińĎani (Serb) clan, from uncle to nephew as the bishops were not allowed to marry. Peter II became vladika in 1830. A brief civil war was suppressed in 1847, a senate replaced the position of ‚Äúcivil governor,‚ÄĚ and progress was made suppressing blood feuding.

In 1851, Danilo II Petrovińá NjegoŇ° became vladika, but in 1852 he married, left the priesthood, assumed the title of knjaz (Prince), and transformed his land into a secular principality. Danilo introduced a modernized legal code, and the first Montenegrin newspaper appeared in 1871. After the assassination of Knjaz Danilo by Todor Kadic, on August 13, 1860, Knjaz Nikola, the nephew of Knjaz Danilo, became the next ruler of Montenegro, which officially confirmed its independence in 1878.

From 1861 to 1862, Nicholas engaged in an unsuccessful war against Turkey, with Montenegro barely holding on to its independence. He was more successful in 1875. Following the Herzegovinian Uprising, partly initiated by his clandestine activities, he again declared war on Turkey. Serbia joined Montenegro, but both were defeated by Turkish forces in 1876, only to try again the following year after Russia decisively routed the Turks. Montenegro was victorious. The results were decisive; 1900 square miles were added to Montenegro's territory by the Treaty of Berlin, the port of Bar and all the waters of Montenegro were closed to all warships, and coastal policing was placed in the hands of Austria. On August 28, 1910, Montenegro was proclaimed a kingdom by Knjaz Nikola, who then became king.

Balkan Wars

The background to the two Balkan Wars in 1912‚Äď1913 lies in the incomplete emergence of nation-states on the fringes of the Ottoman Empire during the nineteenth century. In October 1912, King Nicholas declared war on the Ottoman Empire. The Montenegrin army attacked the Ottoman fortress city of Shkod√ęr, and forced the empire to gather a large army in neighboring Macedonia. The Ottoman army faced a pre-arranged attack by the forces of Greece, Serbia, and Bulgaria. The Treaty of London in 1913 redefined borders in the Balkans. Montenegro doubled in size, receiving half of the former Ottoman territory known as SandŇĺak, but without the city of Shkod√ęr, Montenegro's major goal in the war, which went to the independent country of Albania.

World War I

During World War I, although the Montenegrin army numbered only about 50,000 men, it repulsed the first Austrian attack, resisted the second Austrians invasion of Serbia, and almost succeeded in reaching Sarajevo in Bosnia. However, the Montenegrin army had to retreat before greatly superior numbers of the third Austrian invasion. Austro-Hungarian and German armies overran Serbia and invaded Montenegro in January 1916, and for the remainder of the war remained in the possession of the Central Powers.

King Nicholas fled to Italy and then to France, and the government transferred to Bordeaux. Eventually, Serbian forces liberated Montenegro from the Austrians. A newly-convened National Assembly of Podgorica (Podgorińćka skupŇ°tina), supervised by Serbian forces, accused the king of seeking a separate peace with the enemy and deposed him, and banned his return. Montenegro joined the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes on December 1, 1918, thus becoming the only Allied nation to lose its independence after the war. Pro-independence Montenegrins revolted on the Orthodox Christmas Day, January 7, 1919, against Serbia. The revolt was suppressed in 1924, although guerrilla resistance remained in the Highlands for years after.

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

In the period between the two World Wars, King Alexander (1888-1934) dominated the government, and the period was marked with internal strife, ethnic violence, and rebellions. Although a grandson of Montenegro's king Nicholas, King Alexander worked against the ideas of Montenegro as an independent state and of Montenegrins outside a wider Serb whole.

On January 6, 1929, in response to a political crisis triggered by the murder of Croatian nationalist political leader Stjepan Radińá, King Alexander abolished the constitution Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, prorogued the parliament, and introduced a personal dictatorship. He changed the name of the kingdom to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and changed the internal divisions from the 33 oblasts to nine new banovinas. Montenegro became the Zeta Banovina, and stayed as such until 1941. Untouched by investment or reform, by most economic indicators the region was the most backward in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The Communist Party of Yugoslavia thrived in the region. Alexander was assassinated on Tuesday October 9, 1934, in Marseille.

World War II

During World War II, Italy occupied Montenegro in 1941 and annexed the area of Kotor, where there was a small Roman population, to the Kingdom of Italy. An Independent State of Montenegro was created under fascist control. Within a few months, communists and their sympathizers and non-communist advocates of union with Serbia (bjelaŇ°i), began armed resistance. Meanwhile, Montenegrin nationalists (zelenaŇ°i), supported the Italian administration. Conflict in Montenegro merged with the wider Yugoslav struggle. The strength of the communist party plus the area's remoteness and difficult terrain made it a refuge for Josip Broz Tito's communist Partisan forces.

Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia

Josip Broz Tito became the president of the new Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Creating one of the most dogmatic of the eastern European communist regimes, Tito and his lieutenants abolished organized opposition, nationalized the means of production, distribution, and exchange, and set up a central planning apparatus. Socialist Yugoslavia was established as a federal state comprising six republics: Serbia, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Macedonia and Montenegro, and two autonomous regions within Serbia‚ÄĒVojvodina and Kosovo and Metohija. The Serbs were both the most numerous and the most widely distributed of the Yugoslav peoples.

The federal structure of communist Yugoslavia elevated Montenegro to the status of a republic, thus securing Montenegrin loyalty. Montenegro received large quantities of federal aid, which enabled it to embark for the first time on a process of industrialization. Montenegro became economically stronger than ever. However, economic progress was hampered by difficult communication with the federation. It was during this time that the present capital Podgorica was renamed Titograd, after Tito.

A large number of Montenegrins sided with Soviet leader Josef Stalin in a dispute between the Communist Information Bureau and the Yugoslav leadership in June 1948, when Yugoslavia was expelled from the Cominform and boycotted by socialist countries. Those people paid for their loyalty in subsequent purges.

Break-up of Yugoslavia

In 1980, after Tito's death, the presidency of the subsequent communist regime rotated between representatives of each of the six republics and two provinces. This system contributed to growing political instability, and the rapid decline of the Yugoslav economy, which in turn added to widespread public dissatisfaction with the political system. A crisis in Kosovo, the emergence of Serb nationalist Slobodan MiloŇ°evińá (1941-2006) in Serbia in 1986, and the manipulation of nationalist feelings by politicians, further destabilized Yugoslav politics. Independent political parties appeared in 1988. In 1989, Milosevic, with his vision of a "Greater Serbia" free of all other ethnicities, won the presidency in Serbia. In 1990, multiparty elections were held in Slovenia, Croatia, and in Bosnia-Herzegovina.

Croatia and Slovenia's declarations of independence and the warfare that ensued left Montenegro in a precarious position. The first multiparty elections in 1990 returned the reformed League of Communists to power, confirming Montenegrin support for the disintegrating federation. The republic therefore joined Serbia in fighting the secession of Slovenia and Croatia, and in 1992 it acceded to the ‚Äúthird Yugoslavia,‚ÄĚ a federal republic comprising only it and Serbia.

In 1989, the remains of King Nicholas and other members of the former royal family were returned to Montenegro to be reinterred with great ceremony in Cetinje. This sign of a sense of distinctive Montenegrin identity was matched by lively criticism of the conduct of the war in Bosnia and Herzegovina. In addition, United Nations sanctions against Yugoslavia seriously harmed Montenegro, especially by undermining its lucrative tourist trade. Their impact, however, was somewhat softened by the opportunities created for smuggling.

Union with Serbia

In 1992, after the dissolution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, 95-96 percent of votes cast, in a Montenegro referendum, were for remaining in a federation with Serbia. The turnout was at 66 percent because of a boycott by the Muslim, Albanian, and Catholic minorities as well as of pro-independence Montenegrins. The 1992 referendum was carried out during war time, when propaganda from the state-controlled media favored federation, and was not monitored.

During the Bosnian War and Croatian War (1991-1995), Montenegro participated with its police and paramilitary forces in the attacks on Dubrovnik and Bosnian towns along with Serbian troops. It conducted persecution against Bosniak refugees who were arrested by Montenegrin police and transported to Serb camps in Fońća, where they were executed.

Relations between Montenegro and Serbia began to unravel at the end of 1992, in a disagreement over a dispute over Montenegro's frontier with Croatia, frustration with Serbia's unequal use of power, impatience with Serbia's failure to address economic reform, and disagreements over the conduct of the war in Bosnia and Croatia. In October 1997, the Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro, the ruling party, split into factions that either supported or opposed Serbian President Slobodan MiloŇ°evic. Milorad Djukanovic defeated MiloŇ°evic's prot√©g√© and close ally Momir Bulatovic in the republic's presidential elections.

Just turned 29 years of age, ńźukanovińá was prime minister (1991-1998 and 2003-2006), the youngest prime minister in Europe, and president (1998-2002) of the Republic of Montenegro. A Montenegro-wide roundup of Muslim refugees from Bosnia and their subsequent handover to forces of Bosnian Serbs happened while ńźukanovińá was Prime Minister. In 2003, the prosecutor's office in Naples named ńźukanovińá as a linchpin in the illicit trade which used Montenegro as a transit point for smuggling millions of cigarettes across the Adriatic sea into Italy and into the hands of the Italian mafia for distribution across the EU.

Under ńźukanovińá, Montenegro formed its own economic policy and adopted the Deutsche Mark as its currency. It has since adopted the euro, though it is not formally part of the Eurozone. Subsequent governments of Montenegro carried out pro-independence policies, originally restored by the Liberal Alliance of Montenegro, and political tensions with Serbia simmered despite the political changes in Belgrade. Despite its pro-independence leanings, as the port of Bar, communication facilities, and military targets were bombed by NATO forces during Operation Allied Force in 1999.

Independence

In 2002, Serbia and Montenegro came to a new agreement regarding continued cooperation. In 2003, the Yugoslav federation was replaced in favor of a looser state union named Serbia and Montenegro. A referendum on Montenegrin independence was held on May 21, 2006. A total of 419,240 votes were cast, representing 86.5 percent of the total electorate. Of those, 230,661 votes or 55.5 percent were for independence and 185,002 votes or 44.5 percent were against. The 45,659 difference narrowly surpassed the 55 percent threshold needed under the rules set by the European Union. According to the electoral commission, the 55 percent threshold was passed by only 2300 votes. Serbia, the member-states of the European Union, and the permanent members of the United Nations Security Council have all recognized Montenegro's independence; by doing so they removed all remaining obstacles from Montenegro's path towards becoming the world's newest sovereign state. The 2006 referendum was monitored by five international observer missions, headed by an OSCE/ODIHR monitoring team, and around 3000 observers in total.

On June 3, 2006, the Parliament of Montenegro declared the independence of Montenegro. Serbia did not obstruct the ruling, confirming its own independence and declaring the Union of Serbia and Montenegro ended shortly thereafter. The first state to recognize Montenegro was Iceland, followed by Switzerland. The United Nations, in a vote of the Security Council, extended full membership in the organization to Montenegro on June 22, 2006. Montenegro was confirmed as a member on June 28. In January 2007, Montenegro received full membership in the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank Group. It was admitted to the Council of Europe on May 11 the same year.

Montenegro was a member of NATO's Partnership for Peace program and then became an official candidate for full membership in the alliance. Montenegro applied for a Membership Action Plan on November 5, 2008, which was granted in December 2009. Montenegro was invited to join NATO on December 2, 2015 and on May 19, 2016, NATO and Montenegro conducted a signing ceremony at NATO headquarters in Brussels for Montenegro's membership invitation. Montenegro became NATO's 29th member on June 5, 2017, despite Russia's objections.

Government and politics

Montenegro is a parliamentary representative democratic republic governed by independent executive, legislative, and judicial branches. The president is the head of state, elected directly for a period of five years, and is eligible for a second term. The unicameral national assembly has 81 members elected by direct vote for four-year terms, and is led by a prime minister, who is proposed by president and accepted by the assembly. Ministries act as cabinet.

Suffrage is universal to those aged 18 years of age and over.

Montenegro's judicial branch includes a constitutional court composed of five judges with nine-year terms and a supreme court with justices that have life terms.

Montenegro is divided into 21 municipalities (opŇ°tina), and two urban municipalities, subdivisions of Podgorica municipality: Andrijevica, Bar, Berane, Bijelo Polje, Budva, Cetinje, Danilovgrad, Herceg Novi, KolaŇ°in, Kotor, Mojkovac, NikŇ°ińá, Plav, PluŇĺine, Pljevlja, Podgorica, Golubovci, Tuzi, RoŇĺaje, ҆avnik, Ulcinj, and ŇĹabljak.

Montenegro inherited a 6500-strong military force from the previous combined armed forces of Serbia and Montenegro. It announced plans to reduce the number of active personnel. The force consists entirely of volunteers; conscription was abolished in August 2006. Since Montenegro contained the entire coastline of the former union, it retained practically the entire naval force.

Economy

Industrialization occurred late in Montenegro‚ÄĒthe first factories were built there in the first decade of the twentieth century, followed by wood mills, an oil refinery, a brewery, and electric power plants.

During the era of communism Montenegro experienced a rapid period of urbanization and industrialization. An industrial sector based on electricity generation, steel, aluminum, coal mining, forestry and wood processing, textiles and tobacco manufacture was built up, with trade, overseas shipping, and particularly tourism, increasingly important by the late 1980s.

The loss of previously guaranteed markets and suppliers after the break-up of Yugoslavia left the Montenegrin industrial sector reeling as production was suspended and the privatization program, begun in 1989, was interrupted. The disintegration of the Yugoslav market, and the imposition of the UN sanctions in May 1992 caused the greatest economic and financial crisis since World War II. During 1993, two thirds of the Montenegrin population lived below the poverty line, while frequent interruptions in relief supplies caused the health and environmental protection to drop below the minimum of international standards.

The financial losses under the adverse effects of the UN sanctions were estimated to be approximately $6.39-billion. This period also experienced the second highest hyperinflation in history (three million percent in January 1994) (The highest hyperinflation happened in Hungary after the end of World War II, when inflation there hit 4.19 x 1016 percent).

When in 1997 Milo ńźukanovińá took control, he blamed the policies of Slobodan MiloŇ°evińá for the overall decline of the Montenegrin economy, as well as MiloŇ°evińá's systematic persecution of non-Serbs. Montenegro introduced the German mark as response to again-growing inflation, and insisted on taking more control over its economic fate. This eventually resulted in creation of Serbia and Montenegro, a loose union in which Montenegro mostly took responsibility for its economic policies. This was followed by implementation of faster and more efficient privatization, passing of reform laws, introduction of VAT and usage of euro as Montenegro's legal tender.

Agricultural produce includes (organic) foods, particularly meat (poultry, lamb, goat, veal/beef); milk and dairy produce; honey; fish; vegetables (tomato, pepper, cucumber, and other); fruits (plum, apple, grapes, citrus fruits, olive); high quality wines (Vranac, Krstac, and others); as well as naturally pure potable water.

Montenegro privatized its large aluminum complex - the dominant industry - as well as most of its financial sector, and has begun to attract foreign direct investment in the tourism sector.

Demographics

Population and ethnicity

Differences between Montenegrins and Serbs continue to be controversial. Although existing separately for centuries during the Ottoman period, both groups retained the Orthodox religion and other cultural attributes, including the Cyrillic alphabet. Serbs regard Montenegrins as ‚ÄúMountain Serbs,‚ÄĚ while Montenegrins see themselves as Serb in origin.

Montenegrins are the largest group, although not the majority, with Serbs also a large proportion of the population. There are other smaller numbers of Bosniaks, Albanians, Croats, Roma, Yugoslavs, Macedonians, Slovenes, Hungarians, Russians, Egyptians, Italians, Germans, and others.

Religion

Montenegro is a multireligious country. Although Orthodox Christianity is the dominant religion, there are also numerous adherents of Islam and Catholic Christianity. The dominant Church is the Serbian Orthodox Church - although traces of a forming Montenegrin Orthodox Church are present.The majority of the population are Orthodox Christians, with smaller numbers of Sunni Muslims and Roman Catholics.

Adherents of Orthodox Christianity in Montenegro are predominantly Montenegrins and Serbs. While the Serbs are adherents of the Serbian Orthodox Church and its diocese in Montenegro, the Metropolitanate of Montenegro and the Littoral, Montenegrins are divided between the Serbian Orthodox Church and the Montenegrin Orthodox Church (which is non-canonical and unrecognized).

Islam is the majority religion in Plav, RoŇĺaje, and Ulcinj, and is the dominant religion among Albanians, Bosniaks and Muslims by nationality. Catholic Christianity is mostly present in the region of Boka Kotorska, where there is a significant presence of ethnic Croats. Also, a number of ethnic Albanians are adherents of Catholic Christianity.

Language

The Republic of Montenegro has one official language, the Ijekavian dialect of Serbian, which is spoken by a majority of the population. This replaced Serbo-Croat as Montenegro's official language in the constitution of 1992. This official language is being called, by political organizations in the last years, the Montenegrin language.

Other non-official languages spoken in Montenegro include Albanian, Bosnian, and Croatian. However, Albanian is an official language of the municipality of Ulcinj. Additionally, there are nearly 500 Italians in Montenegro today, concentrated in the Bay of Kotor (the venetian Cattaro) and the coast: they are the descendants of the Venetian speaking population of the areas around Cattaro that belonged for many centuries to the Republic of Venice.

The Montenegrin language is written in Latin and Cyrillic alphabets, but there it is a growing political movement toward calling Montenegrin language the official language of the country and toward using the Latin alphabet.

Men and women

In Montenegro's patriarchal system, women are expected to be subservient to men. Tito's communist regime gave women complete civil and political rights, increasing educational and lifestyle opportunities. However, women are responsible for cooking, cleaning, and child rearing, and those who work outside the home have lower-paying and lower-status jobs than men. Since the civil war, men are more likely to work the few jobs available, and more women have returned to being housewives and mothers.

Marriage and the family

Marriages are generally not arranged. Wedding celebrations can last for days. Before a couple enters their new house, the bride stands in the doorway and lifts a baby boy three times in the belief that will ensure fertility. Divorce became more common during and since the communist era. Several generations tend to live together under the same roof. The first-born son inherits the family's property.

Rural Montenegrins traditionally lived in Slavic zadruga, which were agricultural communities that ranged from a few to 100 related nuclear families, organized patriarchally with a male gospodar as the head. While zadruga no longer exist, the extended family is still important, especially in rural areas, where blood feuding between clans could go on for generations. In the 1970s, traditional patriarchal systems evolved into cooperatives, although they also declined as the population became more urban.

Education

Education in Montenegro is free and compulsory for all children between the age of six and 15. The school curriculum includes the history and culture of all ethnic groups. The language of instruction is Serbian, (Montenegrin, Bosniak, Croatian), and Albanian, depending on the ethnicity of pupils.

Secondary schools are divided in three types: Gymnasium schools (Gimnazija) are the most prestigious, offer four years of broad education and are considered a preparatory school for college. Professional schools (Struńćna Ň°kola) offer three or four years of specialist and broad education. Vocational schools (Zanatska Ň°kola) offer three years of vocational education.

Tertiary education includes higher education (ViŇ°e obrazovanje) and high education (Visoko obrazovanje) level faculties. Colleges (Fakultet) and art academies (akademija umjetnosti) last between four and six years (one year is two semesters long) and award diplomas equivalent to a Bachelor of Arts or a Bachelor of Science degree. Higher schools (ViŇ°a Ň°kola) lasts between two and four years.

Post-graduate education is offered after tertiary level and offers Masters' degrees, Ph.D. and specialization education.

Class

Before World War II, society consisted of a large class of peasants, a small upper class of government workers, professionals, merchants, and artisans, and an even smaller middle class. Communism brought education, rapid industrialization, and a comfortable lifestyle for most. The civil war created extreme differences between the rich and the poor, and left most of the population destitute.

Culture

The culture of Montenegro has been shaped by the Orthodox South Slavic, Central European, and seafaring Adriatic cultures (notably parts of Italy, like the Republic of Venice). Important is the ethical ideal of ńĆojstvo i JunaŇ°tvo, roughly translated as "humanity and bravery." This unwritten code of chivalry, in the old days of battle, resulted in Montenegrins fighting to the death since being captured was considered the greatest shame.

Architecture

Montenegro has a number of significant cultural and historical sites, including heritage sites from the pre-Romanesque, Gothic and Baroque periods. The Montenegrin coastal region is especially well known for its religious monuments, including the Roman Catholic Cathedral of Saint Tryphon in Kotor, which was consecrated in 1166, the basilica of Saint Luke, Our Lady of the Rock (҆krpjela), the Serb Orthodox Savina Monastery, near the city Herceg Novi, and others. Montenegro's medieval monasteries contain thousands of square meters of frescos on their walls. The Byzantine influence in architecture and in religious artwork is especially apparent in the country's interior. The ancient city of Kotor is listed on the UNESCO World Heritage list.

Although Podgorica has become an industrial city, much of the architecture of the older part of the city reflects the Turkish influence of the Ottoman Empire. During World War II, Podgorica was extensively damaged, being bombed over 70 times. After the liberation, mass residential blocks were erected, with basic design typical for countries of the Eastern bloc. Urban dwellers mostly live in apartment buildings. In the country, most houses are modest buildings of wood, brick, or stone.

Cuisine

The traditional dishes of Montenegro's heartland and its Adriatic coast have a distinctively Italian flavor which shows in the bread-making style, the way meat is cured and dried, cheesemaking, wine and spirits, the soup and stew making style, polenta, stuffed capsicum peppers, meatballs, priganice, and RaŇ°tan.

The second influence came from the Levant and Turkey, largely via Serbia: sarma, musaka, pilav, japraci, pita, the popular fast food burek, ńÜevapi, kebab, Turkish sweets like baklava and tulumba, etc.

Hungarian dishes goulash, satarash, djuvech are common. continental Europe added desserts‚ÄĒcr√™pes, doughnuts, jams, and numerous biscuits and cakes. Vienna-style bread is the most prevalent type of bread in the shops.

Breakfast can consist of eggs, meat, and bread, with a dairy spread called kajmak. Lunch is the main meal of the day and usually is eaten at about three in the afternoon. A light supper is eaten at about eight in the evening.

Most common non-alcoholic drink is Pomegranate syrup, while Turkish coffee is almost unavoidable. Mineral water Rada is produced in Bijelo Polje, in the north-eastern highland district of the country. Brandy made with plums, apples or grapes is common. Vranac wine comes from southern Montenegro. NikŇ°ińáko beer is brewed in a range of styles.

Folk dances

Montenegrin folk dances include the Oro and the ҆ota. In the Oro, young men and women form a circle (kolo), then sing, daring somebody to enter the circle to dance. A more daring young man would enter the circle and start to dance imitating an eagle, to impress. Soon, a girl would join, and would also imitate an eagle, but more elegantly. When the couple gets tired, they kiss each other on the cheek and another couple enters the circle to keep the dance going. Usually the men finish Oro by forming a circle, standing on one other's shoulders. Musical instruments are never part of the true Oro.

The ҆ota, which is danced at weddings and gatherings, consists of intricate fast-moving steps, the man and woman moving closer and farther away from each other in time with a fast-paced rhythm. It is common for the woman to shake her handkerchief up in the air while performing the steps. While this dance is performed it is usual for drums to play and other instruments while the audience clap rhythmically to the beat. This dance is done mostly in the Sandzak region of Montenegro.

Epic songs

Traditionally, oral epic poems are delivered accompanied by the gusle, a one-string instrument played by the (guslar), who sings or recites the stories of heroes and battles in decasyllabic verse. These songs have had an immense motivational power, and the guslars commanded almost as much respect as the best warriors.

The epics have been composed and passed on by unknown guslars since the eleventh century. D different versions resulted as other guslars adopted the songs and amended them. Quality control came from listeners, who loudly objected during the performance if the story was inaccurate. Most of the songs were collected, assessed and recorded on paper by Vuk KaradŇĺińá in the nineteenth century.

The most famous recorded guslar-interpreter was Petar Perunovińá - Perun, from the PjeŇ°ivci tribe. He reached his peak during the first few decades of the twentieth century when he made numerous recordings and tours in America and Europe.

The most popular Montenegrin epic song heroes are Bajo Pivljanin, Nikac od Rovina and pop Milo Jovovińá. Contemporary alternative rock author Rambo Amadeus proved with his Smrt Popa Mila Jovovica (The Death of Priest Milo Jovovic) that these songs can be very successfully adapted to the modern art format without losing any of its original appeal.

Music

In the tenth and eleventh centuries, a composer of religious chants (Jovan of Duklja) was the oldest composer known from the Adriatic coast. A twelfth century Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja described the secular use of musical instruments.

Seven liturgies from the fifteenth century, written by a Venetian publisher L.A. Giunta, have been saved in Saint Clara monastery in Kotor. Religious music developed when a Catholic singing academy named "Jedinstvo" (Unity) was formed in Kotor in 1839. Until the musical renaissance of the twentieth century, Montenegrin music was based on the simple traditional instrument, the ''gusle''.

In 1870 in Cetinje, the first Montenegrin Army Music started being formed‚ÄĒalthough not many people applied for the orchestra, because being a soldier was much more valued in Montenegrin society than being a musician. The first music school in Montenegro was founded in 1934 in Cetinje. In the twentieth century, Borislav Taminjzińá, Senad Gadevińá and ŇĹarko Mirkovińá helped bring attention to Montenegrin music.

The first notable Montenegrin classical music composer was Jovan IvaniŇ°evińá (1860-1889), who composed piano miniatures, orchestra, solo and chorus songs. Other nineteenth century composers included Aleksa Ivanovińá and Dragan MiloŇ°evińá, who graduated from Prague music schools. In the first half of the twentieth century, two musical schools developed‚ÄĒone based in Cetinje, and the other one in Podgorica‚ÄĒproducing a number of notable classical music composers.

Literature

The first literary works written in the region are ten centuries old, and the first Montenegrin book was printed 500 years ago. The first state-owned printing press (Printing House of Crnojevińái) was located in Cetinje in 1494, where the first South Slavic book was printed the same year (Oktoih). A number of medieval manuscripts, dating from the thirteenth century, are kept in the Montenegrin monasteries.

On the substratum of traditional oral folk epic poetry, authors like Petar II Petrovińá NjegoŇ° have created their own expression. His epic Gorski Vijenac (The Mountain Wreath), written in the Montenegrin vernacular, presents the central point of the Montenegrin culture, for many surpassing in importance even the Bible.

Although there are works written at least 800 years ago (like the Chronicle of the Priest of Duklja), the most important representatives are writers who lived in nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Sports

The sport of Montenegro revolves mostly around team sports: football, basketball, water polo, volleyball and handball. Also involved are boxing, judo, karate, athletics, table tennis, and chess. Serbia and Montenegro were represented by a single football team in the 2006 FIFA World Cup tournament, despite having formally split just weeks prior to its start. Following this event, this team has been inherited by Serbia, while a new one was organized to represent Montenegro in international competitions. On their 119th session in Guatemala City in July 2007, the International Olympic Committee granted recognition and membership to the newly formed Montenegrin National Olympic Committee. Montenegro was to debut at the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing.

Symbols

A new official flag of Montenegro, adopted in 2004, is based on the royal standard of King Nikola I. This flag was all red with a gold border, a gold coat of arms, and the initials –Ě–Ü in Cyrillic script (corresponding to NI in Latin script) representing King Nikola I. These initials are omitted from the modern flag and replaced wih a golden lion. The Independent State of Montenegro that had existed between 1941 and 1943 used a flag almost identical, according to the Encyclopaedia Britannica. The only difference is that the double-headed eagle was silver in color and not golden.

The national day of July 13 marks the date in 1878 when the Congress of Berlin recognized Montenegro as the 27th independent state in the world and the start of one of the first popular uprisings in Europe against the Axis Powers on July 13, 1941, in Montenegro.

In 2004, the Montenegrin legislature selected a popular Montenegrin traditional song, Oh, the Bright Dawn of May, as the national anthem. Montenegro's official anthem during the reign of King Nikola was Ubavoj nam Crnoj Gori (To our beautiful Montenegro). The music was composed by the King's son Knjaz Mirko. The Montenegrin popular anthem has unofficially been Onamo, 'namo! since King Nikola I wrote it in the 1860s.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ 1.0 1.1 Preliminary results of the 2023 Census of Population, Households, and Dwellings Statistical Office of Montenegro. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Montenegro) International Monetary Fund. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Gini index - Montenegro The World Bank. Retrieved March 14, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boehm, Christopher. Blood revenge: the anthropology of feuding in Montenegro and other tribal societies. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1984. ISBN 9780700602469

- Fleming, Thomas. Montenegro: the divided land. Rockford, IL: Chronicles Press, 2002. ISBN 9780961936495

- King, David C. Serbia and Montenegro. Cultures of the world. New York: Benchmark Books/Marshall Cavendish, 2005. ISBN 9780761418559

- Roberts, Elizabeth. Realm of the Black Mountain: a history of Montenegro. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007. ISBN 9780801446016

- Watkins, Amadeo. New Montenegro and Regional Stability (Balkans). Conflict Studies Research Centre, 2006. ISBN 9781905058716

External links

All links retrieved June 1, 2025.

- Montenegro World Fact Book

- Serbia and Montenegro Countries and Their Cultures

- Montenegro Country Profile BBC

- Montenegro U.S. Department of State

- About Montenegro Montenet

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Montenegro  history

- Geography_of_Montenegro  history

- Podgorica  history

- History_of_Montenegro  history

- Duklja  history

- Principality_of_Zeta  history

- Ivan_I_Crnojevi  history

- 0ura_IV_Crnojevi  history

- Montenegro_Province_Ottoman_Empire  history

- Principality_of_Montenegro  history

- Balkan_Wars  history

- Politics_of_Montenegro  history

- Economy_of_Montenegro  history

- Religion_in_Montenegro  history

- Languages_of_Montenegro  history

- Education_in_Montenegro  history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.