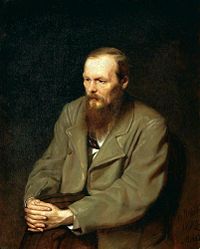

Fyodor Dostoevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (Фёдор Миха́йлович Достое́вский, sometimes transliterated Dostoyevsky (November 11, 1821, – February 9, 1881) was a nineteenth century Russian novelist considered by many critics to be among the greatest writers of his or any age. His works had a profound and lasting impact on twentieth-century thought and fiction. Often featuring characters with disparate and extreme states of the mind, his works exhibit both an uncanny grasp of human psychology as well as penetrating analyses of the political, social, and spiritual state of Russia during his time. Many of his best-known works are prophetic as precursors of modern-day thought and preoccupations.

He is sometimes said to be a founder of existentialism, most notably in Notes from Underground, which has been described by critic Walter Kaufmann as "the best overture for existentialism ever written." Ironically, it was not a worldview which Dostoevsky personally endorsed.

After his arrest and exile to Siberia, his work took a dramatic shift. His greatest concern appears to have been the loss of spiritual values, especially by the rationalists of his day. Progressives of all stripes, taking their cue from Jean Jacques Rousseau, held that human beings were basically good, but that society was corrupt; therefore by changing the social conditions, people's natural goodness would shine through. Dostoevsky's response, as in his Notes from Underground, was simply to portray human irrationality. Rather than argue with socialist ideology, Dostoevsky was satisfied to simply describe human irrationality, which could not be redeemed by merely changing the social order. His novel, Besy, (literally, “Demons”) translated as either The Devils or The Possessed, is often credited with foreseeing the coming of communism to Russia. He feared that rationalism would lead to disastrous consequences in Russia because, as he famously put it, “Without God, everything is permitted.”

Biography

Dostoevsky was the second of six children born to Mikhail and Maria Dostoevsky[4]. Dostoevsky's father Mikhail was a retired military surgeon and a violent alcoholic, who had practiced at the Mariinsky Hospital for the Poor in Moscow. The hospital was located in one of the city's worst areas; local landmarks included a cemetery for criminals, a lunatic asylum, and an orphanage for abandoned infants. This urban landscape made a lasting impression on the young Dostoevsky, whose interest in and compassion for the poor, oppressed and tormented was apparent. Though his parents forbade it, Dostoevsky liked to wander out to the hospital garden, where the suffering patients sat to catch a glimpse of sun. The young Dostoevsky loved to spend time with these patients and hear their stories.

There are many stories of Dostoevsky's father's despotic treatment of his children although letters and personal accounts demonstrate that they had a fairly loving relationship.

Shortly after his mother died of tuberculosis in 1837, Dostoevsky and his brother were sent to the Military Engineering Academy at Saint Petersburg. Fyodor's father died in 1839. Though it has never been proven, it is believed by some that he was murdered by his own serfs. According to a popular account, they became enraged during one of his drunken fits of violence, restrained him, and poured vodka into his mouth until he drowned. Most critics reject this version of events. Its acceptance appears to be based on a similar account that appears in "Notes From the Underground." Most now believe that Mikhail died of natural causes, and a neighboring landowner invented the story of his murder so that he might buy the estate inexpensively.

Epilepsy

Dostoevsky had epilepsy and his first seizure occurred when he was nine years old.[5] Epileptic seizures recurred sporadically throughout his life, and Dostoyevsky's experiences are thought to have formed the basis for his description of Prince Myshkin's epilepsy in his novel The Idiot and that of Smerdyakov in The Brothers Karamazov, among others.

At the Saint Petersburg Academy of Military Engineering, Dostoevsky was taught mathematics, a subject he despised. However, he also studied literature by Shakespeare, Pascal, Victor Hugo and E.T.A. Hoffmann. Though he focused on areas different from mathematics, he did well on the exams and received a commission in 1841. That year, he is known to have written two romantic plays, influenced by the German Romantic poet/playwright Friedrich Schiller: Mary Stuart and Boris Godunov. The plays have not been preserved. Dostoevsky described himself as a "dreamer" when he was a young man, and at that time revered Schiller. However, in the years during which he yielded his great masterpieces, his opinions changed and he sometimes poked fun at Schiller.

Beginnings of a literary career

Dostoevsky was made a lieutenant in 1842, and left the Engineering Academy the following year. He completed a translation into Russian of Balzac's novel Eugénie Grandet in 1843, but it brought him little or no attention. Dostoevsky started to write his own fiction in late 1844 after leaving the army. In 1845, his first work, the epistolary short novel, Poor Folk, published in the periodical The Contemporary (Sovremennik), was met with great acclaim. As legend has it, the editor of the magazine, poet Nikolai Nekrasov, walked into the office of liberal critic Vissarion Belinsky and announced, "a new Gogol has arisen!" Belinsky, the most famous critic of his day, had championed the career of Gogol and the early Dostoevsky as voices of protest against the Tsarist regime. After the novel was fully published in book form at the beginning of the next year, Dostoevsky became a literary celebrity at the age of 24.

In 1846, Belinsky and many others reacted negatively to his novella, The Double, a psychological study of a bureaucrat whose alter ego overtakes his life. Belinsky reacted negatively to this move away from the sympathetic portrayal of the lower classes, and Dostoyevsky's fame began to cool.

Exile in Siberia

Dostoevsky was arrested and imprisoned on April 23, 1849 for being a part of the liberal intellectual group, the Petrashevsky Circle. Tsar Nicholas I responded to the Revolutions of 1848 in Europe by cracking down on internal dissent. On November 16 that year Dostoevsky, along with the other members of the Petrashevsky Circle, was sentenced to death. After a mock execution, in which he and other members of the group stood outside in freezing weather waiting to be shot by a firing squad, Dostoyevsky's sentence was commuted to four years of exile with hard labor at a katorga prison camp in Omsk, Siberia. Dostoevsky described later to his brother the sufferings he went through as the years in which he was "shut up in a coffin." Describing the dilapidated barracks which, as he put in his own words, "should have been torn down years ago," he wrote:

In summer, intolerable closeness; in winter, unendurable cold. All the floors were rotten. Filth on the floors an inch thick; one could slip and fall...We were packed like herrings in a barrel...There was no room to turn around. From dusk to dawn it was impossible not to behave like pigs...Fleas, lice, and black beetles by the bushel...[6]

He was released from prison in 1854, and required to serve in the Siberian Regiment. Dostoevsky spent the following five years as a private (and later lieutenant) in the Regiment's Seventh Line Battalion, stationed at the fortress of Semipalatinsk, now in Kazakhstan. While there, he began a relationship with Maria Dmitrievna Isayeva, the wife of an acquaintance in Siberia. They married in February 1857, after her husband's death.

Return to St. Petersburg

In 1860, he returned to St. Petersburg, where he began a successful literary journal, Time, with his older brother, Mikhail. After it was shut down by the government for publishing an unfortunate article by their friend, Nikolai Strakhov, they began another unsuccessful journal, Epoch. Dostoevsky was devastated by his wife's death in 1864, followed shortly thereafter by his brother's death. Financially crippled by business debts and the need to provide for his brother's widow and children, Dostoevsky sank into a deep depression, frequenting gambling parlors and accumulating massive losses at the tables.

Dostoevsky suffered from an acute gambling compulsion and its consequences. By one account Crime and Punishment, possibly his best-known novel, was completed in a mad hurry because Dostoevsky was in urgent need of an advance from his publisher. He had been left practically penniless after a gambling spree. Dostoevsky wrote The Gambler in similar fashion in order to satisfy an agreement with his publisher Stellovsky. The agreement stipulated that if Stellovsky did not receive a new work, he would claim the copyrights to all of Dostoyevsky's writing.

Dostoevsky traveled to Western Europe, motivated by the dual wish to escape his creditors at home and to visit the casinos abroad. There, he attempted to rekindle a love affair with Apollinaria (Polina) Suslova, a young university student with whom he had had an affair several years prior, but she refused his marriage proposal. Dostoevsky was heartbroken, but soon met Anna Snitkina, a 20-year-old stenographer whom he married in 1867. With her help Dostoevsky wrote some of the greatest novels ever written, including Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov. From 1873 to 1881 he vindicated his earlier journalistic failures by publishing a monthly journal full of short stories, sketches, and articles on current events, titled the Writer's Diary. The journal was an enormous success.

In 1877, Dostoevsky gave a controversial keynote eulogy at the funeral of his friend, the poet Nekrasov. In 1880, shortly before he died, he gave his famous Pushkin speech at the unveiling of the Pushkin Monument in Moscow.

In his later years, Fyodor Dostoevsky lived at the resort of Staraya Russa, which was closer to St. Petersburg and less expensive than German resorts. He died on February 9, 1881, and was interred in Tikhvin Cemetery at the Alexander Nevsky Monastery, St. Petersburg, Russia.

Major Works

From the time of his return to St. Petersburg, until the end of his life, Dostoevsky wrote some of the most important novels in history. Notes from Underground, published in 1864, became the founding document of twentieth-century existentialism, although Dostoevsky himself had no sympathy for the "underground man's" philosophy, using him instead for ironic purposes to poke fun at his positivist philosophy. Written in part as a response to N. G. Chernyshevsky's socialist utopian What Is to Be Done?, it undermines the notion that human beings act based on their own rational best interest, which Chernyshevsky and other disciples of Ludvig Feuerbach, including Karl Marx, had touted as the anthropological principle that would lead humankind into progress and freedom. "Part One" of the novel consists of the ravings of a lunatic, a 40 year old Petersburg intellectual who expounds on his "philosophy" in a rambling, disjointed diatribe. What becomes clear is that this underground man is the dark side of human nature: a neurotic, self-conscious, misanthropic hypochondriac. By simply placing on display this aspect of human nature, Dostoevsky undermines the pretensions in socialist utopianism.

Crime and Punishment is one of the most beloved novels ever written. Like all great novels, it operates on many different levels at once. It is a first-rate crime story, although unlike the conventional "who dunnit," the murder of the old pawnbroker and her sister is presented early in the narrative, and the rest of the novel represents both an attempt to unravel its motive, but also the resolution of the evil deed and the redemption of its anti-hero, Rodion Raskolnikov. In addition to a crime thriller and spiritual allegory, the novel is also the tale of a dysfunctional family. Raskolnikov's "superman theory," which predated and clearly influenced that of German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, was merely a thought experiment until he learns through a letter from home that his sister, Dunya, is throwing her life away to marry a scoundrel in order to "save him" from a life of poverty and secure his future. Further, he learns that his mother is coming to Petersburg, where Raskolnikov is supposed to be attending school, from the provinces, where she lives, apparently in order to better organize and run his life. The "cat and mouse" game that Raskolnikov and the police detective plays together with Raskolnikov's interactions with the prostitute, Sonya, as he seeks forgiveness, form the two poles between which the narrative oscillates. The brilliance of the story lies in Dostoevsky's ability to weave all these narrative threads together.

The Possessed is widely seen as a revolutionary allegory that foreshadows events a generation later. The title literally means "demons," and the collection of characters, from the Luciferian Stavrogin, to the revolutionary organizer Verkhovensky, to the madman Kirilov, is a veritable demonology. Kirilov is a nihilist who sets out to kill himself to prove God's nonexistence, but eventually kills himself in despair. When it was published, the censors refused the chapter entitled, "Stavrogin's Confession," which contained his confession to the rape of a young girl. This led to many unsubstantiated rumors that the chapter was autobiographical.

The Brothers Karamazov was Dostoevsky's last and perhaps greatest novel. Like Crime and Punishment, it is a religious and moral allegory rooted in the struggles of one family, Fyodor Karamazov and his three sons, Dmitri, Ivan, and Alyosha. It is widely understood that each of the sons represents a different human faculty or quality. Dmitri is the sensualist, Ivan the intellectual, and Alyosha the spiritual element. Like Crime and Punishment, the action of the novel centers around a murder mystery, as Fyodor is killed and Dmitri is convicted of the murder. While Dmitri is actually innocent of this deed, the novel raises larger questions of innocence and guilt, and ultimately all the brothers are implicated on some level in the murder. Dmitri and his father are rivals for Grushenka, which forms the basis of his conviction. Ivan provides the rational for the deed that was committed by Smerdyakov, Fyodor's valet and reputed to be his bastard son. Only the saintly Alyosha played no part in the actual murder, but he nonetheless feels guilty for his inability to prevent the murder.

The most famous passage of The Brothers Karamazov is the section on "The Grand Inquisitor." A story told by Ivan to Alyosha, the section is an intellectual's argument with God about the suffering of innocent children. In the story, Christ returns only to find that the church is run by men who, knowing that there is no God, have created a false faith to comfort the masses. Reminiscent of the philosophy of the Devil during Christ's temptation in the wilderness, this new church must exclude Christ because his teachings would cause trouble for their earthly paradise. Ivan eventually has a nervous breakdown, unable to face up to the consequences of such a world. This parable represents the last in a line of Dostoevsky's indictments of the attempt to create a secular paradise without God. Dostoevsky's works presaged many of the struggles of the twentieth century, especially within Russia itself.

Criticism and Influence

Dostoevsky wrote during the era of Realism but he considered his work to be "realism in a higher sense." His novels are compressed in time (many cover only a few days) and this enables the author to get rid of one of the dominant traits of realist prose, the corrosion of human life in the process of the time flux–his characters primarily embody spiritual values, and these are, by definition, timeless. Other obsessive themes include suicide, wounded pride, collapsed family values, spiritual regeneration through suffering (the most important motif), rejection of the West and affirmation of Russian Orthodoxy and Tsarism.

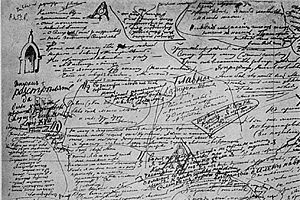

In his day, he was popular, but not considered a great artist. His style was considered "messy," especially in comparison to a technician like Tolstoy, whose language is clean and neat and whose plots are almost mathematical in their precision. Dostoevsky's texts often contain feverishly dramatized scandal scenes. For this reason, he became known as a writer who depicted extreme psychological states. He created situations that permit disparate characters to come into contact with one another, and allowed the conflicts between them to play out.

It was not until the work of literary scholar Mikhail Bakhtin became widely available that the vocabulary to describe Dostoevsky's work developed. In his Problems of Dostoevsky's Poetics, Bakhtin characterized his work as "polyphonic": unlike other novelists, Dostoevsky does not appear to aim for a "single vision," but allowed each of his characters to express their own idea and to interact in dialogic fashion with all the other characters in the novel. Beyond simply describing situations from various angles, Dostoevsky engendered fully dramatic novels of ideas where conflicting views and characters are left to develop unevenly into unbearable crescendo.

This interplay gives his novels a fully dramatic quality. They are more like plays than typical novels. The goal of Dostoevsky’s art is to allow full expression and interaction between these ideas. This creates a "messy" structure, but it is not due to a lack of artistry, but characteristic of Dostoevsky's unique artistic vision.

Anti-Semitism

Dostoevsky has also been noted as having expressed anti-Semitic sentiments. In the recent biography by Joseph Frank, The Mantle of the Prophet, Frank spent much time on A Writer's Diary—a regular column which Dostoevsky wrote in the periodical The Citizen from 1873 to the year before his death in 1881. Frank notes that the Diary is "filled with politics, literary criticism, and pan-Slav diatribes about the virtues of the Russian Empire, [and] represents a major challenge to the Dostoevsky fan, not least on account of its frequent expressions of antisemitism."[7] Frank, in his foreword that he wrote for the book Dostoevsky and the Jews, attempts to place Dostoevsky as a product of his time. Frank notes that Dostoevsky did make antisemitic remarks, but that Dostoyevsky's writing and stance by and large was one where Dostoevsky held a great deal of guilt for his comments and positions that were antisemitic.[8] Steven Cassedy, for example, alleges in his book, Dostoevsky's Religion, that much of the points made that depict Dostoyevsky’s views as an anti-Semite, do so by denying that Dostoevsky expressed support for the equal rights of and for the Russian Jewish population, a position that was not widely supported in Russia at the time.[9] Cassedy also notes that this criticism of Dostoevsky also appears to deny his sincerity in the statements that Dostoevsky made, that he was for equal rights for the Russian Jewish populace, and the Serfs of his own country (since neither group at that point in history had equal rights).[9] Cassedy further notes that the criticism maintains that Dostoevsky was insincere when he stated that he did not hate Jewish people and was not an Anti-Semite.[9] According to Cassedy, this position was maintained without taking into consideration Dostoyevsky's expressed desire to peacefully reconcile Jews and Christians into a single universal brotherhood of all mankind.[9]

Legacy

Dostoevsky's influence has been acclaimed by a wide variety of writers.

American novelist Ernest Hemingway cited Dostoevsky as a major influence on his work in his autobiographical novella A Moveable Feast.

In a book of interviews with Arthur Power (Conversations with James Joyce), James Joyce praised Dostoevsky's influence:

...he is the man more than any other who has created modern prose, and intensified it to its present-day pitch. It was his explosive power which shattered the Victorian novel with its simpering maidens and ordered commonplaces; books which were without imagination or violence.

In her essay The Russian Point of View, Virginia Woolf stated that,

The novels of Dostoevsky are seething whirlpools, gyrating sandstorms, waterspouts which hiss and boil and suck us in. They are composed purely and wholly of the stuff of the soul. Against our wills we are drawn in, whirled round, blinded, suffocated, and at the same time filled with a giddy rapture. Out of Shakespeare there is no more exciting reading.

List of works

Novels

- (1846) Bednye lyudi (Бедные люди); English translation: Poor Folk

- (1849) Netochka Nezvanova (Неточка Незванова); English translation: Netochka Nezvanova

- (1861) Unizhennye i oskorblennye (Униженные и оскорбленные); English translation: The Insulted and Humiliated

- (1862) Zapiski iz mertvogo doma (Записки из мертвого дома); English translation: The House of the Dead

- (1864) Zapiski iz podpolya (Записки из подполья); English translation: Notes from Underground

- (1866) Prestuplenie i nakazanie (Преступление и наказание); English translation: Crime and Punishment

- (1867) Igrok (Игрок); English translation: The Gambler

- (1869) Idiot (Идиот); English translation: The Idiot

- (1872) Besy (Бесы); English translation: The Possessed

- (1875) Podrostok (Подросток); English translation: The Raw Youth

- (1881) Brat'ya Karamazovy (Братья Карамазовы); English translation: The Brothers Karamazov

Novellas and short stories

- (1846) Dvojnik (Двойник. Петербургская поэма); English translation: The Double: A Petersburg Poem

- (1847) Roman v devyati pis'mah (Роман в девяти письмах); English translation: Novel in Nine Letters

- (1847) "Gospodin Prokharchin" (Господин Прохарчин); English translation: "Mr. Prokharchin"

- (1847) "Hozyajka" (Хозяйка); English translation: "The Landlady"

- (1848) "Polzunkov" (Ползунков); English translation: "Polzunkov"

- (1848) "Slaboe serdze" (Слабое сердце); English translation: "A Weak Heart"

- (1848) "Chuzhaya zhena i muzh pod krovat'yu" (Чужая жена и муж под кроватью); English translation: "The Jealous Husband"

- (1848) "Chestnyj vor" (Честный вор); English translation:) "An Honest Thief"

- (1848) "Elka i svad'ba" (Елка и свадьба); English translation: "A Christmas Tree and a Wedding"

- (1848) Belye nochi (Белые ночи); English translation: White Nights

- (1857) "Malen'kij geroj" (Маленький герой); English translation: "The Little Hero"

- (1859) "Dyadyushkin son" (Дядюшкин сон); English translation: "The Uncle's Dream"

- (1859) Selo Stepanchikovo i ego obitateli (Село Степанчиково и его обитатели); English translation: The Village of Stepanchikovo (also published as The Friend of the Family)

- (1862) "Skvernyj anekdot" (Скверный анекдот); English translation: "A Nasty Story"

- (1865) "Krokodil" (Крокодил); English translation: "The Crocodile"

- (1870) "Vechnyj muzh" (Вечный муж); English translation: "The Eternal Husband"

- (1873) "Bobok" (Бобок); English translation: "Bobok"

- (1876) "Krotkaja" (Кроткая); English translation: "A Gentle Creature"

- (1876) "Muzhik Marej" (Мужик Марей); English translation: "The Peasant Marey"

- (1876) "Mal'chik u Hrista na elke" (Мальчик у Христа на елке); English translation: "The Heavenly Christmas Tree"

- (1877) "Son smeshnogo cheloveka" (Сон смешного человека); English translation: "The Dream of a Ridiculous Man"

Non-fiction

- Winter Notes on Summer Impressions (1863)

- A Writer's Diary (Дневник писателя) (1873–1881)

Notes

- ↑ Dostoevsky's other Quixote.(influence of Miguel de Cervantes' Don Quixote on Fyodor Dostoevsky's The Idiot) Fambrough, Preston. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- ↑ Pamuk, Orhan (2006). Istanbul: Memories of a City. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-1400033881.

- ↑ Pamuk, Orhan (2008). Other Colors: Essays and a Story. Vintage Books. ISBN 978-0307386236.

- ↑ The Best Short Stories of Dostoevsky: Translated with an Introduction by David Magarshack. New York: The Modern Library, Random House; 1971.

- ↑ epilepsy.com Classical Writers with Epilepsy Retrieved July 4, 2009. Famous authors with epilepsy.

- ↑ Frank 76. Quoted from Pisma, I: 135-137.

- ↑ Dostoevsky's leap of faith This volume concludes a magnificent biography which is also a cultural history. Orlando Figes. Sunday Telegraph (London). Pg. 13. September 29, 2002.

- ↑ Dostoevsky and the Jews (University of Texas Press Slavic series) (Hardcover) 2 Joseph Frank, "Foreword" pg. xiv. by David I. Goldstein ISBN 0292715285

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Cassedy, Steven (2005). Dostoevsky's Religion. Stanford University Press, 67–80. ISBN 0804751374.

- ↑ The Russian Point of View Virginia Woolf. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cassedy, Steven. Dostoevsky's Religion. Stanford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0804751374

- Goldstein, David. Dostoyevsky and the Jews. University of Texas Press Slavic series, 1981. ISBN 0292715285

- Pamuk, Orhan. Istanbul: Memories of a City. Vintage Books, 2006. ISBN 978-1400033881

- Pamuk, Orhan. Other Colors: Essays and a Story. Vintage Books, 2008. ISBN 978-0307386236

External Links

All links retrieved April 15, 2024.

- FyodorDostoevsky.com—The Definitive Dostoevsky fan site

- Fyodor Dostoevsky's brief biography and works

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.