Chechnya

| Chechen Republic (English) –ß–Ķ—á–Ķ–Ĺ—Ā–ļ–į—Ź –†–Ķ—Ā–Ņ—É–Ī–Ľ–ł–ļ–į (Russian) –Ě–ĺ—Ö—á–ł–Ļ–Ĺ –†–Ķ—Ā–Ņ—É–Ī–Ľ–ł–ļ–į¬†(Chechen) | |

|---|---|

Location of the Chechen Republic in Russia | |

| Coat of Arms | Flag |

Coat of arms of Chechnya |

Flag of Chechnya |

| Anthem: Shtalak's Song (–®–į—ā–Ľ–į–ļ—Ö–į–Ĺ –ė–Ľ–Ľ–ł) | |

| Capital | Grozny |

| Established | January 10, 1993 |

| Political status Federal district Economic region |

Republic Southern North Caucasus |

| Code | 20 |

| Area | |

| Area - Rank |

17,300 km² 76th |

| Population (as of the 2021 Census) | |

| Population - Rank - Density - Urban - Rural |

1,510,824 inhabitants 31st 87.3 inhab. / km² 38.2% 61.8% |

| Official languages | Russian, Chechen |

| Government | |

| Head | Ramzan Kadyrov |

| Legislative body | Parliament |

| Constitution | Constitution of the Chechen Republic |

The Chechen Republic or, informally, Chechnya, (sometimes referred to as Ichkeria, Chechnia, Chechenia or Noxçiyn), is a republic of Russia. It is located in the Northern Caucasus mountains, in the Southern Federal District. It is bordered by Russia on the north, Ingushetia on the west, Republic of Georgia on the southwest and Dagestan to the east and southeast.

In November 1991, following the collapse of the Soviet Union, Chechnya's independence was declared from the Russian Federation. The following year, Checheno-Ingushetia was split into two separate republics; the Republic of Ingushetia which wanted to remain part of Russia and the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria (present day Chechnya) which sought independence.

Since 1994, two wars, terrorist campaigns that have included apartment bombings, suicide attacks, and large-scale hostage crises have occurred. Russian federal control has been re-established. Since then, systematic reconstruction has taken place, though unrest remains an issue.

Geography

Chechens refer to themselves as Noxçi. Theories concerning the name's origin, include: deriving from the village of Nakhsh, the remains of which are high in the mountains, from nexça, or sheep cheese, or nox, a plow. Some say it refers to the Biblical Noah named Nox in Chechen.

The Russian term for the nation - "Chechen" - is also of debated origins, but the prevalent theory is that the ethnonym Chechen derives from the name of the ancient village of Chechana, which in Russian is written as Chechen-aul, situated on the bank of the Argun River, near Grozny.

Situated in the eastern part of the North Caucasus, Chechnya is surrounded by Russian federal territory. It borders North Ossetia and Ingushetia in the west, Stavropol Krai in the north, Dagestan in the east, and Georgia to the south.

The land area of the Chechen republic totals 7452 square miles (19,300km²), which is by comparison between the sizes of Connecticut and New Jersey in the United States.

Chechnya has three regions. In the south is the Greater Caucasus, the peaks of which forms the republic's southern boundary. The highest peak is Mount Tebulosmta (14,741 feet [4493 meters]). The second region consists of the broad valleys of the Terek and Sunzha rivers. The third region, in the north, comprises the level, rolling plains of the Nogay Steppe.

The climate varies according to terrain and proximity to the Caspian Sea, but is generally continental. Average temperatures in January (winter) range from 27¬įF to 23¬įF (-3¬įC to -5¬įC), and in July (summer) from 73¬įF to 77¬įF (23¬įC to 25¬įC). Rainfall averages 12 inches to 16 inches (300mm to 400mm) in the Terek-Kuma lowlands, and 24 inches to 40 inches (600mm to 1000mm) in the south.

The southern area's chief river is the Argun, a tributary of the Sunzha. The Terek and Sunzha rivers cross the republic from the west to the east, where they unite.

Forests of beech, hornbeam, and oak densely cover mountain slopes up to 6500 feet (2000 meters), above which are coniferous forests, then alpine meadows, and finally bare rock, snow, and ice. The Nogay Steppe has sagebrush vegetation and wide areas of sand dunes. Feather-grass steppe occupies the south and southwest, near the Terek River.

Natural hazards include flooding.

Chechnya is criss-crossed by gas and oil pipelines that locals cut into and build small refineries. About 15,000 mini-refineries are believed to be operating there, refining oil into gasoline and furnace fuel. The quality of the refined product is inferior, and the technology used is primitive, and use the lighter part of the oil. The heavier oil is poured down the slope to collect in the rivers Argun, Sundzha, and Terek.

The capital city Grozny, which in Russian means "fearsome" or "terrible," lies on the Sunzha River.

History

A lack of archaeological data makes it difficult to be specific about the early history of the ethnic groups that occupy Chechnya. Caucasian speakers have inhabited the northeastern Caucasus since about 6000 B.C.E., according to both archaeological and linguistic evidence. The Nakh clans, the ancestors of the Chechens and Ingush, lived in the mountains of the region until the sixteenth century, when they began settling in the lowlands. Isolation did not protect the region from invaders. Chechen-Ingush territory coincides with the route along which steppe people entered the mountains and from which mountain people spread to the steppe.

Civilizations in and around the Caucasus

The Caucasian region has often functioned as a buffer zone between rival empires‚ÄĒRoman and Parthian, Byzantine and Arab or Ottoman, Persian, and Russian. Various societies located in and around the territory include:

- The Scythians, a nation of horse-riding nomadic pastoralists who spoke an Iranian languages dominated the Pontic steppe, a vast area stretching from north of the Black Sea as far as the east of the Caspian Sea, from around 770 B.C.E. to 660 C.E.

- Parthia, an Iranian civilization situated in the northeast of modern Iran, existed from between 247 B.C.E. until 220 C.E., and was the arch-enemy of the Roman Empire.

- In classical times, the northern slopes of the Caucasus mountains were inhabited by the Circassians on the west, and the Avars on the east. In between them, the Zygians occupied Zyx, approximately the area covered by north Ossetia, the Balkar, the Ingush and the Chechen republics today. The Zygians were partly nomad shepherds, partly brigands and pirates, for which they had ships specially adapted.

- The Sarmatians, a people originally of Iranian stock, existed in four stages from 700 B.C.E. to 400 C.E. and ranged over territory from the Black Sea to beyond the Volga. They had a nomadic steppe culture which left elaborate burial kurgans.

- The kingdom of Caucasian Albania (Aghbania, Aghvania) was founded in the late fourth century B.C.E. and lasted until 252-253 C.E., when, along with Iberia and Armenia, it was conquered by the Sassanid Empire. Caucasian Albanians were the ancient and indigenous population of modern southern Dagestan and Azerbaijan. Its capital was at Derbent, a city situated on a thin strip of land (three kilometers) between the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus mountains.

- The region that became Chechnya was on the fringe of the Sassanid empire, when, in 252-253 C.E., Caucasian Albania along with Iberia and Armenia, was conquered by the Persian Sassanid Empire (226-651).

- The Khazars were a semi-nomadic Turkic people from Central Asia, many of whom converted to Judaism. In the seventh century C.E., they founded an independent Khaganate in the Northern Caucasus along the Caspian Sea, where over time Judaism became the state religion. At their height, they and their tributaries controlled much of what is today southern Russia, western Kazakhstan, eastern Ukraine, Azerbaijan, large portions of the Caucasus (including Dagestan, Georgia), and the Crimea.

- Sarir, a Avar-dominated medieval Christian state, lasted from the fifth century C.E. to the twelfth century in the mountainous Central Dagestan highlands.

- The Shaddadids were a Kurdish dynasty, who ruled in various parts of Armenia and Arran from 951-1199 C.E. They became vassals to the Seljuqs. From 1047 to 1057, the Shaddadids were engaged in several wars against the Byzantine army.

- The Avar Khanate was a Muslim state which controlled Central Dagestan from the early thirteenth century to the nineteenth century.

Arab conquest

In the middle of the seventh century C.E., Arabs overran Caucasian Albania and incorporated it into the Caliphate. The Caucasian Albanian king Javanshir fought against the Arab invasion of caliph Uthman on the side of the Sassanid Persia. Facing the threat of the Arab invasion on the south and the Khazar offensive on the north, Javanshir had to recognize the Caliph’s suzerainty. The Arabs reunited the territory with Armenia under one governor.

Mongol invasions

Military tensions escalated in 1222, when the region was invaded by Mongols under Subutai, the primary strategist and general of Genghis Khan. Although the Avars pledged their support to Muhammad II of Khwarezm in his struggle against the Mongols, there is no documentation for the Mongol invasion of the Avar lands. The Khanate of Avaristan survived Timur's raid in 1389. As the Mongol authority gradually eroded, new centers of power emerged in Kaitagi and Tarki.

Russian influence begins

Russian influence started as early as the sixteenth century when Ivan the Terrible founded Tarki, situated approximately six kilometers from the Dagestan's capital, Makhachkala in 1559. The Russian Terek Cossack Host was established in lowland Chechnya in 1577 by free Cossacks resettled from Volga River Valley to the Terek River Valley. In the eighteenth century, the steady weakening of Tarki fostered the ambitions of the Avar khans, whose greatest coup was the defeat of the 100,000-strong army of Nadir Shah of Persia in September 1741. Avar sovereigns managed to expand their territory at the expense of free communities in Dagestan and Chechnya. The reign of Umma-Khan (1774-1801) marked the zenith of the Avar ascendancy in the Caucasus.

Caucasian wars

The Caucasian Wars of 1718‚Äď1864, were a series of military actions waged by the Russian Empire against Chechnya, Dagestan, and the Adyghe (Circassians) as Russia sought to expand southward. In 1783, Russia and the eastern Georgian kingdom of Kartl-Kakheti (which had been devastated by Turkish and Persian invasions) signed the Treaty of Georgievsk, according to which Kartli-Kakheti was to receive Russian protection.

In 1785, Chechen leader Sheikh Al Mansur started waging a holy war against the Russians. Mansur hoped to establish a Transcaucasus Islamic state under shari'a law, but was ultimately unable to do so because of both Russian resistance and opposition from many Chechens (many of whom had not been converted to Islam at the time). Sheikh Mansur was captured in 1791 and died a few years later. He remains a legendary national hero of the Chechen people.

Russia absorbs Dagestan, Chechnya

In 1810, Ingushetia voluntarily joined Imperial Russia, and from 1803-1813, Dagestan was incorporated into the empire. Imperial Russian forces under Aleksey Yermolov began moving into highland Chechnya in 1830 to secure Russia's borders with the Ottoman Empire. In the course of prolonged war, the Chechens, along with many peoples of the Eastern Caucasus, united into the Caucasian Imamate and resisted fiercely, led by the Dagestani heroes Ghazi Mohammed, and Gamzat-bek.

Imam Shamil (1797-1871), an Avar political and religious leader of anti-Russian resistance in the Caucasian War, was the third Imam of Dagestan and Chechnya (1834-1859). He led the resistance from 1834, and in 1845, Shamil's forces achieved their most dramatic success when they withstood a major Russian offensive. Shamil remained successful while the Russians were occupied with the Crimean War (1854-1856). But the Russians used larger forces in their later campaigns, Shamil was captured in 1859, and Chechnya was absorbed into the Russian Empire.

Russian occupation caused a prolonged wave of emigration until the end of the nineteenth century. Many of Shamil's followers migrated to Armenia. Thousands of highlanders moved to Turkey and other countries of the Middle East, while Cossacks and Armenians settled in Chechnya. During the Russo-Turkish War, 1877-1878 the highlanders rose against Russia again, but were defeated.

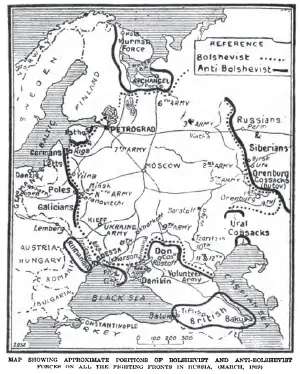

Chechen rebellion would characteristically flame up whenever the Russian state faced a period of internal uncertainty. Rebellions occurred during the Russo-Turkish War, the Russian Revolution of 1905, the Russian Revolution of 1917, Russian Civil War, and Collectivization.

Mountainous republic formed

On January 20, 1921, Chechnya and Ingushetia joined the Republic of the Mountaineers of the North Caucasus (1917‚Äď1920), a shortlived state later forming the republics of Chechnya, Ingushetia, North Ossetia-Alania, and Dagestan. With a population of about one million, its capital was initially at Vladikavkaz, then Nazran, and finally Buynaksk.

During the Russian Civil War, the Mountaineers were engaged in fierce clashes against the invasive White Movement troops of General Anton Denikin's Volunteer Army. The fighting ended in January 1920, when Denikin's army was defeated by the XI Red Army. The advancing Red Army was at first greeted by red flags in the villages of the Northern Caucasus but the promises of autonomous rule made by the Bolsheviks went unrealized.

Soviet republic

In June 1920, the Red Army of Bolshevik Russia occupied the mountainous republic, and the legal government was forced out. In January 1921, the Soviet Mountain Republic of the Russian SFSR was established. On November 30, 1922, the Chechen Autonomous Oblast of RSFSR was separated, and on July 7, 1924, the Ingush Autonomous Oblast of RSFSR was separated. Chechnya was combined with Ingushetia to form the autonomous republic of Chechen-Ingushetia on December 5, 1936. The republic included not only the ethnically Chechen mountains but also large stretches of steppe inhabited by the Terek Cossacks.

World War II insurgency

The Chechens again rose up against Soviet rule in 1940, led by guerrilla fighter, journalist, and poet Hasan Israilov (1910-44). A descendant of the legendary rebel leader Imam Shamil, Israilov had been jailed for writing an editorial accusing communist party officials of looting and corruption. In 1940, after hearing of Finland's resistance against Soviet aggression, Israilov led an armed insurrection, and established a rebel government in Galanchozh. The rebels declared war on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, relying on the support of the German Wehrmacht. In some areas up to 80 percent of men were involved in the insurrection. It is known that the Soviet Union diverted bombers from use at the siege of Stalingrad for use against the rebels, causing losses primarily to the civilian population.

On September 25, 1943, German paratroopers took the Grozny petroleum refinery, to prevent its destruction by the Red Army, and united with the rebels, in a bid to hold the refinery until the German 1st Tank Army arrived. However, from September 25-27 the German tank army was defeated and the paratroopers retreated. The insurrection caused many of the 40,000 Chechen and Ingush soldiers fighting in the Red Army to desert.

The Chechens and Ingush were found collectively guilty of collaborating with the German invaders. On orders from Russian president Joseph Stalin, the entire population of the republic was exiled to Kazakhstan. Over a quarter died. The Checheno-Ingush ASSR was transformed into Grozny oblast, and parts were given to North Ossetia, Georgian SSR and Dagestan ASSR.

The Chechens were allowed to return in 1957, four years after Stalin's death in 1953. Territories that had been transferred to Ossetia and Dagestan were not returned to restored Checheno-Ingushetia. On the other hand Naursky district (then populated mainly by Russians) that wasn't part of the pre-1944 republic remained a part of the republic. Russification policies towards Chechens continued after 1956, with Russian language proficiency required in many aspects of life and for advancement in the Soviet system.

Collapse of the Soviet Union

In November 1990, the Chechen republic issued the declaration of its sovereignty, and in May 1991 an independent Chechen-Ingush Republic was pronounced. Boris Yeltsin's Russian Federation opposed independence of the region, arguing, first, that Chechnya had not been an independent entity within the Soviet Union‚ÄĒas the Baltic, Central Asian, and other Caucasian States had‚ÄĒand did not have a right under the Soviet constitution to secede; second, that other republics of Russia, such as Tatarstan, would join the Chechens and secede from the Russian Federation if they were granted that right; and third, that Chechnya was a major oil center and hence would hurt the country's economy and control of oil resources.

In August 1991, former Soviet air force general Dzhokhar Dudayev, a Chechen politician, stormed a session of the Chechen-Ingush ASSR Supreme Soviet and took control of government. Dudayev was elected Chechen president in October, and in November he declared Chechnya independent from the Russian Federation. In 1992 Checheno-Ingushetia divided into two separate republics: Chechnya and Ingushetia. Dudayev pursued nationalistic, anti-Russian policies.

From 1991 to 1994, tens of thousands of people of non-Chechen ethnicity, mostly Russians, left the republic amid reports of violence against the non-Chechen population. Chechen industry began to fail as a result of many Russian engineers and workers leaving or being expelled. During the undeclared Chechen civil war, factions both sympathetic and opposed to Dudayev fought for power, sometimes in pitched battles with the use of heavy weapons.

In March 1992, the opposition attempted a coup d'état, but their attempt was crushed. A month later, Dzhokhar Dudayev introduced direct presidential rule, and in June 1993, dissolved the parliament to avoid a referendum on a vote of non-confidence. Federal forces dispatched to the Ossetian-Ingush conflict were ordered to move to the Chechen border in late October 1992, and Dudayev declared a state of emergency and threatened general mobilization if the Russian troops did not withdraw from the Chechen border. After staging another coup attempt in December 1993, the opposition organized a provisional council as a potential alternative government for Chechnya, calling on Moscow for help.

First Chechen War

The First Chechen War occurred when Russian forces attempted to stop Chechnya from seceding in a two-year period lasting from 1994 to 1996, and resulted in Chechnya's de facto independence from Russia. After the initial campaign of 1994‚Äď1995, culminating in the devastating Battle of Grozny from December 1994 to January 1995, Russian federal forces attempted to control the mountainous area of Chechnya but were set back by Chechen guerrilla warfare and raids on the flatlands (including mass hostage takings beyond Chechnya) in spite of Russia's overwhelming manpower, weaponry, and air support.

Chief Mufti Akhmad Kadyrov's declaration that Chechnya was waging a Jihad (Muslim holy war) against Russia raised the specter that Jihadis from other regions and even outside Russia would enter the war. By one estimate, in all up to 5000 non-Chechens served as foreign volunteers; they were mostly Caucasian and included possibly 1500 Dagestanis, 1000 Georgians and Abkhazians, 500 Ingushes and 200 Azeris, as well as 300 Turks, 400 Slavs from Baltic states and Ukraine, and more than 100 Arabs and Iranians. Many of them were motivated by the anti-Russian Nationalism, rather than Islamism.

A turning point in the war came with the Budyonnovsk hospital hostage crisis, that took place from June 14-19, 1995, when a group of 80 to 150 Chechen separatist fighters led by Shamil Basayev (1965-2006), a militant Islamist, a leader of a Chechen separatist movement, and a self-proclaimed terrorist, attacked the southern Russian city of Budyonnovsk (pop. 100,000), some 70 miles north of the border with the Russian republic of Chechnya. In the city and the hospital they took between 1500 and 1800 hostages, mainly civilians and including about 150 children and a number of women with newborn infants, and demanded then end of the First Chechen War and beginning of direct negotiations with Chechen separatist leadership.

Russian MVD and FSB OSNAZ special forces tried to storm the hospital compound at dawn on the fourth day, meeting fierce resistance. On June 18, negotiations between Russian Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin and Shamil Basayev led to a compromise which became a turning point for the First Chechen War. In exchange for the hostages, and faced with widespread demoralization of the Russian forces, Russian President Boris Yeltsin declared a ceasefire in 1996 and signed a peace treaty a year later.

The war was disastrous for both sides. Conservative casualty estimates give figures of 7500 Russian military dead, 4000 Chechen combatants dead, and no fewer than 35,000 civilian deaths‚ÄĒa minimum total of 46,500 dead. Others have cited figures in the range 80,000 to 100,000.

Second Chechen War

The Second Chechen War was a military campaign conducted by Russia starting August 26, 1999, in which Russian forces largely recaptured the separatist region of Chechnya. In August 1999, Shamil Basayev began an unsuccessful incursion into the neighboring Russian republic of Dagestan. In September the following year, a series of apartment bombings took place in several Russian cities, including Moscow. In response, after a prolonged air campaign of retaliatory strikes against the Ichkerian regime (which was officially seen as the culprit of both the bombings and the incursion) a ground offensive began in October 1999.

Better-organized and planned than the first Chechen War, the Russian Federal forces were able to quickly re-establish control over most regions and after the re-capture of Grozny in February 2000, the Ichkerian regime fell apart, although guerrilla activity continues in the southern mountainous regions. Nonetheless Russia was successful in installing a pro-Moscow Chechen regime, and eliminating the most prominent separatist leaders including former President Aslan Maskhadov and Basayev.

The war bolstered the domestic popularity of Vladimir Putin as the campaign was started one month after he had become Russian prime minister. Putin established direct rule of Chechnya in May 2000. The following month, Putin appointed Akhmad Kadyrov interim head of the government. This development met with early approval in the rest of Russia, but the continued deaths of Russian troops dampened public enthusiasm. In 2003, Chechen voters approved a new constitution that devolved greater powers to the Chechen government but kept the republic in the federation. The Russian-backed Chechen president was killed, on May 9, 2004, in a bomb blast during the parade in Grozny, allegedly carried out by Chechen guerrillas

Between June 2000 and September 2004, Chechen insurgents added suicide attacks to their tactics. During this period there were 23 Chechen related suicide attacks in and outside Chechnya. The profiles of the Chechen suicide bombers have varied just as much as the circumstances surrounding the bombings, most of which targeted military or government-related targets.

On October 23, 2002, about 40 armed Chechen Islamic militants who claimed allegiance to the separatist movement in Chechnya, seized a crowded Moscow theater, took 850 hostages, and demanded the withdrawal of Russian forces from Chechnya and an end to the Second Chechen War. After a two-and-a-half day siege, Russian OSNAZ forces pumped an unidentified gas into the building's ventilation system and raided it. Officially, 39 of the terrorists were killed by Russian forces, along with at least 129 of the hostages.

Both sides of the war carried out multiple assassinations. The most prominent of these included the February 13, 2004, killing of exiled former separatist Chechen President Zelimkhan Yandarbiyev in Qatar.

On September 1, 2004, Secondary School Number One in Beslan, a town located in North Ossetia-Alania, was seized by a group of at least 32 Chechen Islamist terrorists, and more than 1200 schoolchildren and adults were taken hostage. The siege ended on September 3 with a chaotic shootout between the terrorists and Russian security forces. According to official data, 344 civilians were killed, 186 of them children, and hundreds more wounded.

The exact death toll from the Second Chechen War is unknown, yet estimates range from tens of thousands to hundreds of thousands dead or missing, mostly civilians in Chechnya. No clear figures for Russian losses have been released, but military deaths in two wars are thought to at least equal the losses suffered during the Soviet war in Afghanistan of 15,000.

On October 7, 2006, Russian journalist and human rights activist Anna Politkovskaya, who was well known for her opposition to the Chechen conflict and Russian President Putin, was found shot dead in the elevator of her apartment building. Previously, she had been arrested and subjected to mock execution by Russian military forces in Chechnya, and she was poisoned on the way to Beslan, but survived and continued her reporting. Putin was publicly accused by Alexander Litvinenko of ordering her murder. Litvinenko subsequently died from poisoning by radioactive polonium.

In April 2009, Russia ended its counter-terrorism operation and pulled out the bulk of its army. Three months later, the leader of the separatist government, Akhmed Zakayev, called for a halt to armed resistance against the Chechen police force starting on August 1, 2009. However, insurgency in the North Caucasus continued even after this date.

Government and politics

Government system

On March 23, 2003, a new Chechen constitution, that was passed in a referendum, granted the Chechen Republic a significant degree of autonomy, but still tied it firmly to the Russian Federation and Moscow's rule as a secular, autonomous republic. According to that constitution, the president, who heads executive power, is elected by direct vote to a term of four years and can serve two terms in succession. The bicameral legislature comprises the Council of the Republic, consisting of 21 deputies elected directly in single-mandate election districts by secret ballot, which reviews laws passed by the People's Assembly, consisting of 40 deputies elected directly. The judiciary comprises a constitutional court, courts of justice, federal courts, the high court of the Chechen Republic, the Court of arbitrage of the Chechen Republic, as well as district and specialized courts.

Chechnya has 15 districts, five cities and towns, three urban settlements, 213 selsoviets (administrative unit), 324 rural localities, and 27 uninhabited rural localities.

Former separatist elected president

The former separatist religious leader (mufti) Akhmad Kadyrov was elected president with 83 percent of the vote in an unmonitored election on October 5, 2003. Incidents of ballot stuffing and voter intimidation by Russian soldiers and the exclusion of separatist parties from the polls were subsequently reported by the OSCE monitors.

After Kadyrov's assassination in 2004, Sergey Abramov was appointed to the position of acting prime minister. However, since 2005 Ramzan Kadyrov (son of Akhmad Kadyrov) was caretaker prime minister, and in 2007 he was appointed Head of the Chechen Republic. He has a large private militia referred to as the Kadyrovtsy. The militia ‚Äď which began as his father's security force ‚Äď has been accused of killings and kidnappings by human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch.

Separatist government

There is a separatist Ichkeria government recognized only by Georgia, and the Taliban government of Afghanistan. The president was Aslan Maskhadov, the Foreign Minister was Ilyas Akhmadov, who was the spokesman for Maskhadov. Aslan Maskhadov had been elected in an internationally monitored election in 1997 for four years, prolonged one additional year in 2001. Maskhadov was unable to participate in the 2003 presidential election, since separatist parties were banned, and he faced accusations of terrorist offenses in Russia. Maskhadov moved to the separatist-controlled areas of the south at the onset of the Second Chechen War.

Russian forces killed Maskhadov on March 8, 2005, an event widely criticized since it left no legitimate Chechen separatist leader to conduct peace talks with. Akhmed Zakayev, Deputy Prime Minister and a Foreign Minister under Maskhadov, was appointed shortly after the 1997 election and was living under asylum in England in 2006. Abdul Khalim Saidullayev, a relatively unknown Islamic judge, was chosen to replace Maskhadov, but he too was killed by Russian special forces. The successor of Saidullayev became Doku Umarov.

Human rights

Human Rights Watch reports that pro-Moscow Chechen forces under the effective command of President Ramzan Kadyrov, as well as federal police personnel, used torture to get information about separatist forces. Human rights groups criticized the conduct of the 2005 parliamentary elections as unfairly influenced by the central Russian government and military.

The Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre reports that after hundreds of thousands of people fled their homes after inter-ethnic and separatist conflicts in Chechnya in 1994 and 1999, more than 150,000 people still remain displaced in Russia more than a decade after the beginning of armed conflict.

Economy

Traditionally, Chechens were sheep farmers, with men living a seminomadic life accompanying the herds through mountain pastures. Grain agriculture was the mainstay in the lowlands. High mountain villages traded livestock and eggs for grain in lowland bazaars. Theft of horses and other robbery provided extra cash. Maize has been the staple grain since the seventeenth century, and there was no traditional production of manufactured items for trade. Nearby oil fields made Grozny a center of industry and urban employment.

During the wars, the Chechen economy collapsed. Gross domestic product, if reliably calculable, would be only a fraction of the prewar level. Problems with the Chechen economy had an effect on the federal Russian economy - a number of financial crimes during the 1990s were committed using Chechen financial organizations. Chechnya has the highest ratio within Russian Federation of financial operations made in US Dollars to operations in Russian Roubles. There are many counterfeit US Dollars printed there.

As an effect of the war, approximately 80 percent of the economic potential of Chechnya was destroyed, and the petroleum industry was the first sector to be rebuilt.

Despite economic improvements, smuggling and bartering continue to comprise a significant part of Chechnya's economy.

The railway communication was restored in 2005, and Grozny's Severny airport was reopened in 2007 with three weekly flights to Moscow. Most of the city's infrastructure was destroyed and many continued to live in ruined buildings without heating and running water, even as electricity was mostly restored since 2006, as the city has undergone substantial reconstruction.

Demographics

Ethnicity

There are nearly 60 distinct ethnic groups living in the Caucasus region, and 50 languages. Chechens make up the great majority of the republic's population. Other groups include Russians, Kumyks, Ingush, and a host of smaller groups, each accounting for less than 0.5 percent of the total population. At the end of the Soviet era, ethnic Russians (including Cossacks) comprised about 23 percent of the population, but they now number much less and emigration is still happening.

There are also significant Chechen populations residing in other Russian regions (especially in Dagestan and Moscow city). Outside Russia, countries with significant Chechen populations are Georgia, Turkey, Jordan and Syria. These are mainly descendants of people who had to leave Chechnya during the Caucasian Wars around 1850.

Religion

Before the adoption of Islam, Chechens partook in numerous rituals, many of them pertaining to farming. These included rain rites, a celebration that occurred on the first day of plowing, as well as the Day of the Thunderer Sela, and the Day of the Goddess Tusholi.

The country converted to the Sunni Muslim religion between the sixteenth and the nineteenth centuries under the Ottoman Empire. Each clan is led by a spiritual mystic. Some adhere to a Sufi mystic branch of Sunni Islam called Muridism. About half of Chechens belong to Sufi brotherhoods, or tariqa. The two Sufi tariqas that spread in the North Caucasus were the Naqshbandiya, which is particularly strong in Dagestan and eastern Chechnya, and the Qadiriya, which has most of its adherents in the rest of Chechnya and Ingushetia.

Salafism, often used interchangeably with Wahhabism, which seeks to revive a practice of Islam that more closely resembles the religion during the time of the Prophet Mohammad, was introduced to the population in the 1950s. Some of the rebels involved in the Chechen war‚ÄĒparticularly those who followed Shamil Basayev‚ÄĒare Salafists, but the majority are not.

The once strong Russian minority in Chechnya, mostly Terek Cossacks, are predominately Russian Orthodox, although presently only one church exists in Grozny.

Marriage and the family

Couples traditionally marry out of the clan but within the tribe. Dating has not been part of traditional Chechen social life. Usually marriages are arranged, but elopement also common. Elopement appeared like bride kidnap but was usually arranged in advance with the knowledge of the girl's mother. In arranged marriages, the consent of the bride was not required, and there was a bride-price, traditionally payable in livestock, but now is usually a negotiated gift, paid by the groom's family to the couple. Marriage by kidnapping was to avoid a high bride-price, although it could spark a feud. A nuclear family makes up the usual household when space and resources permit.

A man avoids contact with his wife's parents and defers to her brothers and sisters. A woman avoids her husband's parents, but by the time the first child is born she can converse with them. Orphaned children were raised by a father's brother or by the nearest relative, and a childless family might raise a son of the husband's brother as their own.

Divorce has become common, especially in cities. The bride-price can be returned to the husband's family if the wife is at fault, or it may be retained by the wife if the husband was at fault. A divorced or widowed woman with children can hope to remarry only if she leaves the children with the husband's family.

Polygyny, the practice of a man having multiple wives, was traditionally practiced, but was outlawed during the Soviet regime. However, with the rise in Islamic tradition, polygyny has revived but is not widely practiced.

Clan culture

Chechen society is structured around 130 Teip, or clans. The teips are based more on land than on blood and have an uneasy relationship in peacetime, but are bonded together during war. Teips are further subdivided into gars (branches), and those into nekye (patronymic families). The Chechen social code is called ''Nokhchallah'' where Nokhcho (Noxçuo) stands for "Chechen" and may be loosely translated as "Chechen character," or "Chechenness." The Chechen code of honor implies moral and ethical behavior, generosity and the will to safeguard the honor of women. Many Chechens consider themselves loyal to their teip, and for this reason it has been difficult to forge a united political front against Russia.

Language

Chechen and Russian are the languages used in the Republic. Chechen belongs to the Vaynakh or North-central Caucasian linguistic family, which also includes Ingush and Batsb. Some scholars place it in a wider Iberian-Caucasian super-family. Other dialects include Ingush, which has speakers in Ingushetia, and Batsi, which is the spoken language of the cattle-farmers in part of Georgia, which had never been written. After 1991, Chechen nationalism and rising anti-Russian sentiment resulted in a drive to remove Russian words from the Chechen language. A new school curriculum to increase the teaching of the Chechen language was developed, and Chechen publications and media broadcasting increased.

Education

Children begin school at the age of seven, and continue to attend school until tenth grade. Universities and trade institutes offer further career training to high school graduates. Girls sometimes do not seek higher education, choosing instead to marry and raise a family. People in rural areas often remain at home and work in the family farming business.

Class

Traditional Chechen-Ingush society is highly egalitarian. The only hierarchical relationships are those of age, kinship, and earned social honor. Under Russia, a new aristocracy emerged based on service, and after the 1917 Revolution society was divided into workers, peasants, and intellectuals. Traditional class divisions persisted into the Soviet period, when communist elites had special access to goods, services, and housing.

Culture

A Chechen village

Single-storey houses with a flat roof, constructed with rock, wood, clay, and straw, are the most common type of buildings in mountainous Chechnya. Several buildings - the living quarters, a tower, and the outhouses - made up a family holding. Villages were well protected, close to pastures, water, and arable land. They look like haphazard agglomerations of buildings, lacking straight streets, and were built without plans, on the bank of a river or along a road. A mountain village had 20 to 25 family units, whereas a flatland village had over 400. Scarce land was divided between kins‚ÄĒthe more kinsmen, the bigger the land entitlement. Every village had a main square for public gatherings dominated by a mosque.

Each house was divided into two fully detached rooms, with two entrances. The master of the house lived and received guests in one room, while the other room belonged to the woman and the children. The Chechen house has no windows ‚Äď a square floor-to-ceiling opening was closed for the night with a shutter. A fire constantly burning in an earthen fireplace, provided for cooking and heating. A cooking pot hooks to a chain that hangs from the ceiling. A clay-covered wicker smoke stack extends from one meter above the fire through the roof. Furniture includes an armchair for the master of the house, a low table, and a few low benches. People sleep on the floor. Mattresses, lengths of felt, rugs, carpets and blankets were kept, together with tableware, on wide shelves that lined the inside walls of both rooms. Wooden chests line the wall.

Music

The pondur is the oldest Chechen musical instrument, comprising of three strings and a wooden casing. Being similar to the Russian balalaika, the difference lies in the casing: the pondur is rather long, is made of one solid block of wood and has a soft, rustling voice. The reed-pipe is played on a summer solstice marking the day of Pkh'armat, a legendary figure who brought fire to the Chechens via burning embers on a reed stalk, which was said to have burnt small holes in the reed, thus forming the reed-pipe. The chiondarg which resembles a fiddle, was played in the fields and was believed to make grain grow faster and yield better crops.

The first recordings of Chechen music were made by an exiled member of the Decembrist society in the middle of the nineteenth century. Composer A.A.Davidenko visited villages of Chechnya in the 1920s and made recordings of a number of historical, ritual, love and dance tunes. Thirty arrangements of Chechen folk tunes were published, in one volume, in Moscow, in 1926.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Avtorkhanov, Abdurakhman, and Marie Broxup. The North Caucasus Barrier: The Russian Advance towards the Muslim World. New York, NY: St. Martin's Press, 1992. ISBN 9780312075750

- Baiev, Khassan, Ruth Daniloff, and Nicholas Daniloff. The Oath: A Surgeon under Fire. New York, NY: Walker & Co., 2003. ISBN 9780802714046

- Bird, Chris. To Catch a Tartar: Notes from the Caucasus. London: John Murray, 2003. ISBN 9780719565069

- Bornstein, Yvonne. Eleven Days of Hell: My True Story of Kidnapping, Terror, Torture and Historic FBI & KGB Rescue. Bloomington, IN: Author House, 2004. ISBN 1418494070

- Brown, Archie, Michael Charles Kaser, and Gerald Stanton Smith. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Russia and the Former Soviet Union. Cambridge [Cambridgeshire]: Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 9780521355933

- Dunlop, John B. Russia Confronts Chechnya: Roots of a Separatist Conflict. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 9780521636193

- Evangelista, Matthew. The Chechen Wars: Will Russia go the way of the Soviet Union? Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0815724988

- Gall, Carlotta, and Thomas De Waal. Chechnya: Calamity in the Caucasus. New York, NY: New York University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0814731321

- Lieven, Anatol. Chechnya: Tombstone of Russian Power. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1998. ISBN 9780300073980

- Murphy, Paul. The Wolves of Islam: Russia and the Faces of Chechen Terror. Dulles, VA: Brassey's, 2004. ISBN 9781574888300

- PolitkovskaiÔł†aÔł°, Anna. A Small Corner of Hell: Dispatches from Chechnya. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press,2007. ISBN 978-0226674339

- Wixman, Ronald. Language Aspects of Ethnic Patterns and Processes in the North Caucasus. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago, Dept. of Geography, 1980. ISBN 9780890650981

External links

All links retrieved December 4, 2023.

- Chechen-Ingush Countries and Their Cultures

- Chechens Countries and Their Cultures

- Regions and territories: Chechnya BBC News

- Chechnya Human Rights Watch

- Chechnya profile BBC News

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Chechnya  history

- Chechen_people  history

- Grozny  history

- History_of_Chechnya  history

- Shaddadid  history

- Mountainous_Republic_of_the_Northern_Caucasus  history

- First_Chechen_War  history

- Budyonnovsk_hospital_hostage_crisis  history

- Second_Chechen_War  history

- Moscow_theater_hostage_crisis  history

- Beslan_school_hostage_crisis  history

- Shamil_Basayev  history

- Aslan_Maskhadov  history

- Anna_Politkovskaya  history

- Government_of_Chechnya  history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.