Acts, Book of

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (47 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | {{epname}} | + | {{epname|Acts, Book of}} |

| + | |||

{{Books of the New Testament}} | {{Books of the New Testament}} | ||

| − | |||

| − | Acts | + | The '''Acts of the Apostles''' is a book of the [[New Testament]]. It is commonly referred to as the '''Book of Acts''' or simply '''Acts'''. The title "Acts of the Apostles" (Greek ''Praxeis Apostolon'') was first used as its title by [[Irenaeus]] of Lyon in the late second century. |

| − | + | Acts tells the story of the [[Early Christian]] church, with particular emphasis on the ministry of the apostles [[Saint Peter|Peter]] and [[Paul of Tarsus]], who are the central figures of the middle and later chapters of the book. The early chapters, set in [[Jerusalem]], discuss Jesus' [[Resurrection of Jesus|Resurrection]], his [[Ascension]], the [[Pentecost|Day of Pentecost]], and the start of the apostles' ministry. The later chapters discuss Paul's conversion, his ministry, and finally his arrest, imprisonment, and trip to [[Rome]]. A major theme of the book is the expansion of the [[Holy Spirit]]'s work from the Jews, centering in [[Jerusalem]], to the [[Gentile]]s throughout the [[Roman Empire]]. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | {{ | + | It is almost universally agreed that the author of Acts also wrote the [[Gospel of Luke]]. The traditional view is that both Luke and Acts were written in the early 60s C.E. by a companion of Paul named [[Luke the Evangelist|Luke]], but many modern scholars believe these books to have been the work of an unknown author at a later date, sometime between 80 and 100 C.E. Although the objectivity of the Book of Acts has been seriously challenged, it remains, together with the letters of Paul, one of the most extensive sources on the history of the early Christian church. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Summary== | ==Summary== | ||

| − | The author begins with a prologue addressed to a person named [[Theophilus (Biblical)|Theophilius]] and references "my earlier book"—almost certainly the [[Gospel of Luke]]. This is immediately followed by a narrative in which | + | ===Prologue=== |

| + | The author begins with a prologue addressed to a person named [[Theophilus (Biblical)|Theophilius]] and references "my earlier book"—almost certainly the [[Gospel of Luke]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | This is immediately followed by a narrative in which the resurrected [[Jesus]] instructs the disciples to remain in [[Jerusalem]] to await the gift of the [[Holy Spirit]]. They ask him if he intends now to "restore the kingdom to Israel," a reference to his mission as the Jewish [[Messiah]], but Jesus replies that the timing of such things is not for them to know (1:6-7). After this, Jesus ascends into a cloud and disappears, a scene known to Christians as the [[Ascension]]. Two "men" appear and ask why they look to the sky, since Jesus will return in the same way he went.<ref>Some believe this refers to his second coming on the clouds, while others hold that, since the disciples are told not to look to the sky for his return, the second coming will not occur on the clouds.</ref> | ||

| + | |||

| + | From this point on, Jesus ceases to be a central figure in the drama of Acts, while the Holy Spirit becomes the prime actor, performing great miracles through the disciples and bringing the Gospel to all people. | ||

===The Jerusalem church=== | ===The Jerusalem church=== | ||

| − | [[ | + | The apostles, along with [[Mother Mary|Jesus' mother]], his brothers,<ref>Catholic tradition, which affirms Mary's perpetual [[virgin]]ity, denies that these "brothers" are Mary's sons, interpreting them to be either cousins or Joseph's sons by a previous marriage.</ref> and other followers, meet and elect [[Matthias]] to replace [[Judas Iscariot]] as a member of [[The Twelve]]. On [[Pentecost]], the [[Holy Spirit]] descends on them. The [[apostle]]s hear a great wind and witness "tongues of flames" descending on them. Thereafter, the apostles have the miraculous power to "[[glossolalia|speak in tongues]]" and when they address a crowd, each member of the crowd hears their speech in his own native language. Three thousand people reportedly become believers and are baptized as a result of this miracle (2:1-40). |

| − | + | [[Peter]], along with John, preaches to many in [[Jerusalem]], and performs miracles such as healings, the [[Exorcism|casting out of evil spirits]], and the raising of the dead (ch. 3). A controversy arises due to Peter and John preaching that Jesus had been resurrected. [[Sadducee]]an priests—who, unlike the [[Pharisee]]s, denied the doctrine of the [[resurrection]]—have the two apostles arrested. The High Priest, together with other Sadduceean leaders, question the two but fear punishing them on account of the recent miracle at the [[Temple of Jerusalem|Temple]] precincts. Having earlier condemned Jesus to the Romans, the priests command the apostles not to speak in Jesus' name, but the apostles make it clear they do not intend to comply (4:1-21). | |

| − | [[ | + | The growing community of [[Jewish Christians]] practices a form of communism: "selling their possessions and goods, they gave to anyone as he had need." (1:45) The policy is strictly enforced, and when one member, [[Ananias]], withholds for himself part of the proceeds of a house he has sold, he and his wife are both slain by the [[Holy Spirit]] after attempting to hide their sin from Peter (5:1-20). |

| − | + | As their numbers increase, the believers are increasingly persecuted. Once again the Sadducees move against them. Some of the apostles are arrested again. The leader of the [[Pharisee]]s, [[Gamaliel]], however, defends them, warning his fellow members of the [[Sanhedrin]] to "Leave these men alone! Let them go! For if their purpose or activity is of human origin, it will fail. But if it is from God, you will not be able to stop these men; you will only find yourselves fighting against God." (5:38-39) Although they are flogged for disobeying the High Priest's earlier order, the disciples are freed and continue to preach openly in the Temple courtyards. | |

| − | + | An internal controversy arises within the Jerusalem church between the Judean and Hellenistic Jews,<ref>Hellenistic Jews, here, were apparently those whose origins were in the [[diaspora]] and were less connected to the [[Jerusalem]] tradition of the early believers in Jesus</ref> the latter alleging that their widows were being neglected. [[The Twelve]], not wishing to oversee the distributions themselves, appointed [[Saint Stephen|Stephen]] and six other non-Judean Jews for this purpose so that the apostles themselves can concentrate on preaching (6:1-7. Many in Jerusalem soon join the faith, including "a large number of priests." | |

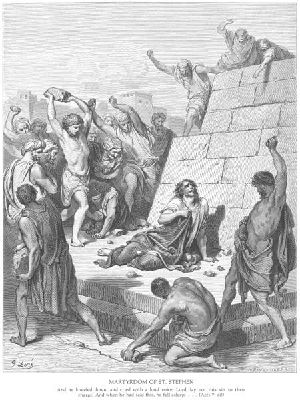

| − | + | [[Image:Stephen-martyred.jpg|thumb|The martyrdom of Saint Stephen]] | |

| − | + | Although the apostles themselves thus manage to stay out of trouble and gain [[religious conversion|converts]] among the Jewish religious establishment, Stephen soon finds himself embroiled in a major controversy with other Hellenistic Jews, who accuse him of [[blasphemy]]. At his trial, Stephen gives a long, eloquent summary of providential history, but concludes by accusing those present of resisting the [[Holy Spirit]], killing the [[prophet]]s, and murdering the [[Messiah]]. This time, no one steps forward to defend the accused, and Stephen is immediately stoned to death, becoming the first Christian [[martyr]] (ch. 6-7). One of those present and approving of his death is a Pharisee named Saul of Taursus, the future [[Saint Paul]]. | |

| − | + | As a result of Stephen's confrontation with the Temple authorities, a widespread [[persecution]] breaks out against those Jews who affirm Jesus as the [[Messiah]]. Many believers flee Jerusalem to the outlying areas of [[Judea]] and [[Samaria]], although the apostles remain in Jerusalem. Saul is authorized by the High Priest to arrest believers and put them in prison. | |

| − | |||

| − | As a result of Stephen's confrontation with the Temple authorities, a widespread persecution breaks out against those Jews who affirm Jesus as Messiah. Many believers flee Jerusalem to the outlying areas of Judea and Samaria, although the apostles remain in Jerusalem. Saul is authorized by the High Priest to arrest believers and put them in prison. | ||

===The faith spreads=== | ===The faith spreads=== | ||

| − | In [[Samaria]], a | + | In [[Samaria]], a [[disciple]] named Philip<ref>This is not the apostle, since they have stayed in Jerusalem. Later he is identified as one of the "seven," a [[deacon]], like Stephen.</ref> performs [[miracle]]s and influences many to believe. One of the new believers is [[Simon Magus]], himself a miracle worker with a great reputation among the [[Samaritans]]. [[Saint Peter|Peter]] and [[John the Beloved|John]] soon arrive in order to impart the gift of the [[Holy Spirit]]—something Philip is apparently unable to do—to the newly baptized. [[Simon Magus]] is amazed at this gift and offers the apostles money that he too may learn to perform this miracle. Peter takes offense at this offer, declaring, "may your money perish with you." (8:20) Simon immediately repents and asks Peter to pray to God on his behalf. The apostles continue their journey among the Samaritans, and many believe.<ref>In later tradition, Simon is thought to be the first of the [[Gnosticism|Gnostic heretics]]. The term "[[simony]]"—the buying of ecclesiastical office—is derived from his name.</ref> |

| − | Philip converts an | + | Philip also converts an Ethiopian eunuch, the first [[Gentile]] official reported to join the new faith (8:26-40). |

| − | ===Paul's | + | ===Paul's conversion=== |

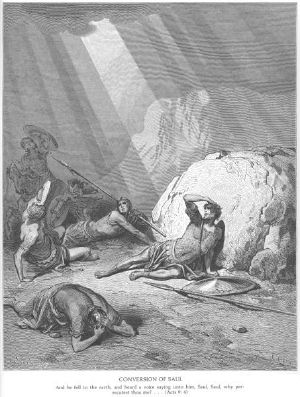

| − | Paul of Tarsus, also known as Saul, is the main character of the second half of Acts, which deals with the work of the Holy Spirit as it moves beyond Judea and begins to bring large numbers of Gentiles into faith in the [[Gospel]]. In one of the [[New Testament]]'s most dramatic episodes, Paul travels on the road to Damascus, where he intends to arrest Jews who profess faith in Jesus. | + | [[Image:Paul's-conversion.jpg|thumb|The conversion of Saul]] |

| + | [[Paul of Tarsus]], also known as Saul, is the main character of the second half of Acts, which deals with the work of the Holy Spirit as it moves beyond Judea and begins to bring large numbers of Gentiles into faith in the [[Gospel]]. In one of the [[New Testament]]'s most dramatic episodes, Paul travels on the road to [[Damascus]], where he intends to arrest Jews who profess faith in [[Jesus]]. "Suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground" (9:3-4) and Paul becomes blind for three days (9:9). In a later account Paul hears a voice saying: "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me? … I am Jesus" (26:14-15). In Damascus, Paul is cured from his blindness and becomes as ardent believer. The [[Jerusalem]] community is suspicious and fearful of him at first, but he wins the [[apostle]]s' trust and faces danger from the Hellenistic Jews whom he debates. After this, the church in [[Judea]], [[Galilee]], and [[Samaria]] enjoys a period of growth and relative peace. (9:31) | ||

| − | Peter, meanwhile, conducts several miraculous healings, including the raising of the female disciple | + | ===Gentile converts=== |

| + | Peter, meanwhile, conducts several miraculous healings, including the raising of the female disciple Tabitha from the dead (9:40). During Peter's travels, a Roman [[centurion]] named [[Cornelius]] receives a revelation from an [[angel]] that he must meet Peter.<ref>Although he is a [[Gentile]], Cornelius is already a believer in the God of the Jews. These "[[God-fearer]]s" would become a primary audience of Christian preaching, which promised them salvation without having to be circumcised or following all of the Mosaic laws.</ref> Cornelius sends an invite Peter to dine with him. Peter himself, meanwhile, has a dream in which God commands him to eat non-[[kosher]] food, which Peter has never done previously (ch. ten). The next day, Peter eats at Cornelius' home and preaches there. Several Gentiles are converted, and Peter baptizes them.<ref>The fact that these men are baptized into the faith without first being circumcised is significant in showing that not only Paul, but Peter, too, practiced this tradition.</ref> Back in [[Jerusalem]], Peter is criticized by the "circumcised believers" for entering a Gentile home and eating with non-Jews. His critics are silenced, however, when Peter relates the above events.<ref>Many scholars believe these chapters are related to the incident in Galatians 3, in which Paul criticizes Peter for refusing to eat with Gentiles. Some hold that the incidents of chapter ten are misplaced in the narrative, while others believe them to be fictional.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Soon a sizable group of Gentile believers has joined the faith in Syrian [[Antioch]], the [[Roman Empire]]'s third largest city. The [[Jerusalem church]] sends [[Barnabas]], a [[Levite]], to minister to them.<ref>As a Levite, Barnabas would be particularly knowledgeable about Jewish tradition. He is thus an interesting choice as Jerusalem's representative to the first Christian community composed largely of Gentiles.</ref>Barnabas finds Paul in Tarsus and brings him to Antioch to assist in the mission. It is here that the followers of Jesus are first called Christians. Christian prophets, one of whom is named [[Agabus]], come to Antioch from [[Jerusalem]] and predict to the Anitochans that a famine will soon spread across the Roman world. A collection is taken up to send aid to the Judean church. | |

| − | + | Peter, meanwhile, is imprisoned by King [[Herod Agrippa]],<ref>"Kings" such as Agrippa ruled by the consent of [[Rome]] and were often perceived as Roman agents by local populations such as the Jews.</ref> but miraculously escapes. Agrippa himself is soon slain by an angel after allowing himself to be honored instead of God (ch. 12). | |

| − | + | Probably several years later, [[Barnabas]] and Paul set out on a mission to further spread the faith (13-14). They travel first to [[Selucia]] and [[Cyprus]], and then to [[Asia Minor]], preaching in synagogues and visiting existing Christian congregations throughout the region. They have many adventures, often running afoul of Jewish leaders.<ref>One reason for this persecution is that Paul often addresses the "Gentiles who worship God" in the synagogues, offering them complete membership in the new faith without circumcision or having to adhere to the entire Mosaic Law. In the synagogues, such "God-fearers" (and their financial support) were welcome, but they could not attain full membership without circumcision.</ref>In [[Lystra]], after a miracle of healing, the local [[Gentile]] community hails [[Barnabas]] as [[Zeus]] and Paul as [[Hermes]], titles they, of course, reject. They establish local churches and appoint leaders to guide them, finally returning to Antioch for a long stay. | |

| − | + | ===The council of Jerusalem=== | |

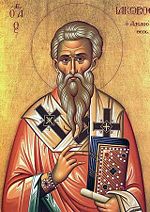

| + | [[Image:Saint James the Just.jpg|thumb|150px|James "the Just," leader of the Jerusalem church]] | ||

| + | At Antioch, a controversy arises when members from [[Jerusalem]] arrive and insist that Gentile believers must be circumcised (15:1). Paul and Barnabas then travel to Jerusalem and consult with the apostles—a meeting known as the [[Council of Jerusalem]] (15). Paul's own record of the meeting is apparently recorded in [[Galatians]] 2.<ref>However, the account differs significantly from Acts, and some argue Gal. 2 is a different meeting.</ref> Some members of the Jerusalem church are strict [[Pharisee]]s and hold that [[circumcision]] is required for [[Gentile]]s who join the faith. Paul and his associates strongly disagree. | ||

| − | + | After much debate, [[James]], the brother of [[Jesus]] and leader of the Jerusalem church, decrees that Gentile members need not follow all of the [[Mosaic Law]], and in particular, they do not need to be circumcised. Paul's party, however, is required to accept that Gentiles must obey the commandments against eating food sacrificed to idols, meat that is not fully cooked, and meat of strangled animals, as well as from sexual immorality.<ref>Paul's own letters call into question whether he would have agreed with these stipulations, for he often argues that obedience to [[dietary laws]] is not necessary at all for Gentiles. He also says in 1 Corinthians 8 that [[idol]]s are not really gods, so only those with weak consciences are harmed by this action; but it is still good practice to refrain from eating such meat publicly, because those who think idols are indeed gods should not be led to think that Christians are honoring this false gods. This policy leaves the true believer free to eat such meats in private, and since much meat was ritually slaughtered by [[pagan]] butchers, this would likely be a frequent practice.</ref> (15:29) | |

| − | == | + | ===Paul and Barnabas part ways=== |

| + | Paul and Barnabas now plan a second missionary journey. However, they have a falling out over whether [[John Mark]] should accompany them, Paul objecting on the grounds that he had deserted them during their first journey and returned to Jerusalem.<ref>Some believe that the true nature of Paul's split with Barnabas was over the question of table fellowship with Gentiles, mentioned in Galatians 3. Others add that Paul may have believed Mark to be a spy whose loyalties were with the conservative elements of the Jerusalem church.</ref> Paul continues on without Barnabas or Mark, who are not heard from again. Paul takes [[Silas]] with him and goes to [[Derbe]] and then [[Lystra]], where they are joined by [[Timothy]], the son of a Jewish woman and a Greek man. According to Acts 16:3, Paul circumcises Timothy before continuing his journey, in order to satisfy the objections of conservative Jews.<ref>Considering Paul's views on circumcision in his letter to the [[Galatians]], such an act constitutes a major concession by Paul. Some scholars consider the episode a fiction.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Paul spends the next several years traveling through western [[Asia Minor]] and founds the first Christian church in [[Philippi]]. He then travels to [[Thessalonica]], where he stays for some time before departing for [[Greece]]. In [[Athens]], he visits an altar with an inscription dedicated to the [[Unknown God]], and when he gives his speech on the [[Areios Pagos|Areopagos]], he declares that he worships that same Unknown God, which he identifies as the Christian God. In Corinth, he settles for more than a year but faces charges that he was "persuading the people to worship God in ways contrary to the law." (18:12–17) Typically, Paul begins his stay in each city by preaching in the [[synagogue]]s, where he finds some sympathetic hearers but also provokes stiff opposition. At [[Ephesus]], he gains popularity among the Gentiles, and a riot breaks out as idol-makers fear that Paul's preaching will harm their business, associated with the [[Temple of Artemis]], one of the [[Seven Wonders of the World]] (ch. 19). | |

| − | |||

| − | ; | + | During these travels, Paul not only founds and strengthens several churches; he also collects funds for a major donation he intends to bring to [[Jerusalem]].<ref>The theme of Paul's uneasy relations with Jerusalem runs just beneath the surface of Acts, leading many to believe his donation is, in effect, an attempt to show both his good will and his value, despite his controversial teachings.</ref> His return is delayed by shipwrecks and close calls with the authorities, but finally he lands in [[Tyre]], where he is warned by the Holy Spirit not to continue on to Jerusalem. Likewise in [[Caesarea]], Paul is warned by the prophet Agabus that he will be arrested if he goes to the Holy City. Paul stubbornly refuses to be dissuaded, however. |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Paul trials and final journey=== | |

| − | + | Upon Paul's arrival in Jerusalem, he is met by James, who confronts him with the rumor that he is teaching against the [[Law of Moses]]: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>"You see, brother, how many thousands of Jews have believed, and all of them are zealous for the law. They have been informed that you teach all the Jews who live among the Gentiles to turn away from Moses, telling them not to circumcise their children or live according to our customs. What shall we do?" (21:20-22)</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | To prove that he himself is "living in obedience to the law," Paul accompanies some fellow [[Jewish Christians]] who are completing a [[Nazirite|vow]] at the [[Temple of Jerusalem|Temple]] (21:26) and pays the necessary fees for them. Paul is recognized, however, and he is nearly beaten to death by a mob, accused of the sin of bringing Gentiles into the Temple confines (21:28). Paul is rescued from being flogged when he informs a Roman commander that he is a citizen of Rome. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Paul is then brought before the [[Sanhedrin]]. He runs afoul of the [[Sadducee]]an High Priest, but cleverly plays to his fellow [[Pharisee]]s on the council by claiming that the real issue at stake is the doctrine of the [[resurrection]] of the dead (23:6). Paul wins a temporary reprieve but is imprisoned in [[Caesarea]] after a plot against his life is uncovered. There, before the Roman governor [[Felix]], Paul is confronted again by the High Priest, and once again Paul insists that, although he is indeed following of "[[The Way]]," the real reason he is being accused by the Sadducees is that he believes in the doctrine of the resurrection, as do most Pharisees. Paul remains imprisoned in Caesaria for two years. He later preaches before [[Agrippa II]] and is finally sent by sea to Rome, where he spends another two years under house arrest (28:30-31). From there he writes some of his most important letters. | |

| − | + | The Book of Acts does not record the outcome of Paul's legal troubles. It concludes: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>For two whole years Paul stayed there in his own rented house and welcomed all who came to see him. Boldly and without hindrance he preached the kingdom of God and taught about the Lord Jesus Christ.</blockquote> | |

| − | + | ==Themes and style== | |

| − | + | ===Salvation to the Gentiles=== | |

| + | One of the central themes of Acts is the idea that Jesus' teachings were for all humanity—[[Jews]] and [[Gentiles]] alike. Christianity is presented as a religion in its own right, rather than a sect of [[Judaism]]. Whereas the [[Jewish Christians]] were circumcised and adhered to the [[kosher]] dietary laws, the [[Pauline Christianity]] featured in Acts did not require Gentiles to be circumcised; and its list of Mosaic commandments required for Gentiles was limited to a small number. Acts presents the movement of the Holy Spirit first among the Jews of Jerusalem in the opening chapters, then to the Gentiles and Jews alike in the middle chapters, and finally to the Gentiles primarily in the end. Indeed, the final statement of Paul in Acts can be seen as the basic message of the Book of Acts itself: "I want you to know that God's salvation has been sent to the Gentiles, and they will listen!" (28:28) | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===The Holy Spirit=== | ||

| + | As in the [[Gospel of Luke]], there are numerous references to the [[Holy Spirit]] throughout Acts. The book uniquely features the "baptism in the Holy Spirit" on Pentecost and the subsequent spirit-inspired speaking in tongues (1:5, 8; 2:1-4; 11:15-16). The Holy Spirit is shown guiding the decisions and actions of Christian leaders (15:28; 16:6-7; 19:21; 20:22-23) and the Holy Spirit is said to "fill" the apostles, especially when they preach (1:8; 2:4; 4:8, 31; 11:24; 13:9, 52). | ||

| − | === | + | ===Concern for the oppressed=== |

| + | The [[Gospel of Luke]] and Acts both devote a great deal of attention to the oppressed and downtrodden. In Luke's Gospel, the impoverished are generally praised (Luke 4:18; 6:20–21) while the wealthy are criticized. Luke alone tells the parable of the [[Good Samaritan]], while in Acts a large number of [[Samaritans]] join the church (Acts 8:4-25) after the Jerusalem authorities launch a campaign to persecute those who believe in [[Jesus]]. In Acts, attention is given to the suffering of the early Christians, as in the case of Stephen's martyrdom, Peter's imprisonments, and Paul's many sufferings for his preaching of Christianity. | ||

| − | + | ===Prayer and speeches=== | |

| + | Prayer, too, is a major motif in both the Gospel of Luke and Acts. Both books have a more prominent attention to [[prayer]] than is found in the other gospels. | ||

| − | + | Acts is also noted for a number of extended speeches and sermons from Peter, Paul, and others. There are at least 24 such speeches in Acts, comprising about 30 percent of the total verses.<ref> [http://www.geocities.com/paulntobin/lukespeech.html Fictitious Speeches in Acts]. ''www.geocities.com''. Retrieved August 6, 2007.</ref> | |

| − | + | ===The "Acts" genre=== | |

| + | The word "Acts" (Greek ''praxeis'') denotes a recognized [[genre]] in the [[ancient world]], "characterizing books that described great deeds of people or of cities."<ref>D. A. Carson, Douglas J. Moo, and Leon Morris. ''An Introduction to the New Testament.'' (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005), 181.</ref> Many ancient works also tell marvelous tales of travels to foreign places, and Acts fits with this type as well, complete with stories of shipwrecks, escapes from prison, miraculous healings and slayings, interventions by angelic beings, descriptions of famous foreign buildings, and dramatic close encounters with both mobs and legal authorities. | ||

| − | + | There are several such books in the [[New Testament apocrypha]], including the [[Acts of Thomas]], the [[Acts of Paul]] (and [[Thecla]]), the [[Acts of Andrew]], and the [[Acts of John]]. | |

| − | === | + | ==Authorship== |

| − | + | While the precise identity of the author is debated, the consensus of scholarship holds that the author was an educated Greek [[Gentile]] man writing for an audience of Gentile Christians. There is also substantial evidence to indicate that the author of the Book of Acts also wrote the [[Gospel of Luke]]. The most direct evidence comes from the prefaces of each book, both of which are addressed to [[Theophilus (Biblical)|Theophilus]], probably the author's patron. Furthermore, the preface of Acts explicitly references "my former book" about the life of Jesus--almost certainly the work we know as the Gospel of Luke. | |

| − | + | There are also clear linguistic and theological similarities between the Luke and Acts. Because of their common authorship, the Gospel of Luke and Acts of the Apostles are often jointly referred to as ''Luke-Acts.'' | |

| − | + | ===Luke the physician=== | |

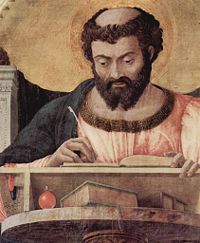

| − | + | [[Image:Andrea Mantegna 017.jpg|thumb|200px|Portrait of Luke, as conceived by Andrea Mantegna, c. 1453-1454]] | |

| + | The traditional view is that the Book of Acts was written by the physician [[Luke the Evangelist|Luke]], a companion of Paul. This Luke is mentioned in Paul's [[Epistle to Philemon]] (v.24), and in two other epistles which are traditionally ascribed to Paul ([[Colossians]] 4:14 and [[2 Timothy]] 4:11). | ||

| − | + | The view that Luke-Acts was written by the physician Luke was nearly unanimous among the early [[Church Fathers]] who commented on these works. The text of Luke-Acts provides important hints that its author was either himself a companion of Paul, or that he used sources from one of Paul's companions. The so-called "'we passages" are often cited as evidence of this. Although the bulk of Acts is written in the [[Grammatical person|third person]], several brief sections are written from a first-person plural perspective.<ref>Acts 16:10–17, 20:5–15, 21:1–18, and 27:1–28:16</ref> For example: "After Paul had seen the vision, we got ready at once to leave for Macedonia… we put out to sea and sailed straight for Samothrace." (16:10-11) It has also been argued that the level of detail used in the narrative describing Paul's travels suggests an eyewitness source. Some claim that the vocabulary used in Luke-Acts suggests its author may have had medical training. | |

| − | + | Others believe that Acts was written by an anonymous Christian author who may not have been an eyewitness to any of the events recorded within the text. In the preface to Luke, the author refers to having eyewitness testimony "handed down to us" and to having undertaken a "careful investigation," but the author does not claim to be an eyewitness to any of the events. Except for the "we" passages in Acts, the narrative of Luke-Acts is written in the third person, and the author never refers to himself as "I" or "me." The "we passages" are thus regarded as fragments of a source document which was later incorporated into Acts by the author. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Scholars also point to a number of apparent theological and factual discrepancies between Luke-Acts and [[Pauline Epistles|Paul's letters]]. For example, Acts and the Pauline letters appear to disagree about the number and timings of Paul's visits to [[Jerusalem,]] and Paul's own account of his conversion is different from the account given in Acts. Similarly, some believe the theology of Luke-Acts is also different from the theology espoused by Paul in his letters. Acts moderates Paul's opposition to circumcision and the kosher dietary laws, and it downplays bitter disagreements between Paul and Peter, and Paul and Barnabas. To some, this suggests that the author of Luke-Acts did not have significant contact with Paul, but instead relied on other sources for his portrayal of Paul. | |

| − | ==Sources== | + | ===Sources=== |

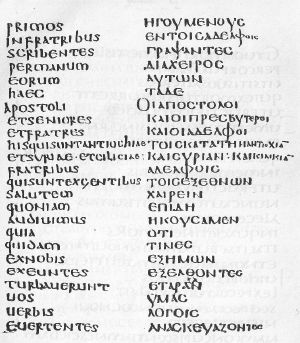

[[Image:Codex laudianus.jpg|thumb|right|Acts 15:22–24 from the seventh-century ''Codex laudianus'' in the [[Bodleian Library]], written in parallel columns of [[Latin]] and [[Greek language|Greek]].]] | [[Image:Codex laudianus.jpg|thumb|right|Acts 15:22–24 from the seventh-century ''Codex laudianus'' in the [[Bodleian Library]], written in parallel columns of [[Latin]] and [[Greek language|Greek]].]] | ||

| − | The author of Acts likely relied upon | + | The author of Acts likely relied upon written sources, as well as oral tradition, in constructing his account of the early church and Paul's ministry. Evidence of this is found in the prologue to the Gospel of Luke, where the author alluded to his sources by writing, "Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word." |

| − | It is generally believed that the author of Acts did not have access to a collection of [[Pauline epistles|Paul's letters]]. One piece of evidence suggesting this is that although half of Acts centers on Paul, Acts never directly quotes from the epistles nor does it even mention Paul writing letters. Additionally, the epistles and Acts disagree about the | + | It is generally believed that the author of Acts did not have access to a collection of [[Pauline epistles|Paul's letters]]. One piece of evidence suggesting this is, that although half of Acts centers on Paul, Acts never directly quotes from the epistles nor does it even mention Paul writing letters. Additionally, the epistles and Acts disagree about the chronology of Paul's career. |

| − | + | ===Date=== | |

| + | [[conservative Christianity|Conservative Christian]] scholars often date the Book of Acts quite early. For example, [[Norman Geisler]] believes it was written between 60-62 C.E..<ref> [http://www.bethinking.org/resource.php?ID=233 Dating of the New Testament, Dr. Norman Geisler] ''www.bethinking.org''. Retrieved August 6, 2007.</ref> Others have suggested that Acts was written as a defense of Paul for his upcoming trial in Rome.<ref>John L. Mauch. ''Paul On Trial: The Book Of Acts As A Defense Of Christianity.'' (Thomas Nelson, 2001)</ref>. Arguing for an early date is the fact that Paul has not yet died when the book ends, nor is there any reference to Jewish rebellion against Rome and the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, which took place in 70 C.E. | ||

| − | + | However, Acts 20:25 suggests that the author knows of Paul's death: "I know that none of you.. will ever see me again." Moreover many scholars believe that Luke did have knowledge of the Temple's destruction (Luke 19:44; 21:20), and that his Gospel was written during the reign of Emperor Domitian (81-96). One of Luke's purposes in writing to Theophilus, possibly a Roman official whom he addresses as "excellency," may have been to demonstrate that the Christians were loyal to Rome, unlike many Jews. The fact that Acts shows no awareness of Paul's letters means that Luke probably wrote before Paul's epistles were collected and distributed. Thus, liberal scholarship tends to put the date of Acts at somewhere between 85 and 100 C.E..<ref> See for example William Baird, "Acts of the Apostles," in the ''Interpreters Bible,'' 1971.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The place of composition is still an open question. For some time Rome and Antioch have been in favor, but some believe internal evidence points to the Roman province of [[Asia Province|Asia]], particularly the neighborhood of [[Ephesus]]. | |

| − | + | ==Historicity== | |

| + | The question of authorship of Acts is largely bound up with that of the historicity of its contents. Conservative scholars view the book as being basically accurate while skeptics view it as historically unreliable, its purpose being basically propagandistic and faith-driven. | ||

| − | + | Beyond these basic differences in attitude, faithful Christians as well as secular scholars have devoted much effort to discussing the accuracy of Acts. It is one of the few Christian documents that can be checked in many details against other known contemporary sources, namely the letters of Paul, one of Acts' own main characters. | |

| − | + | ===Acts. vs. Paul's epistles=== | |

| + | Attention has been drawn particularly to the account given by Paul of his visits to Jerusalem in Galatians as compared with Acts, to the account of Paul's conversion, his attitude toward the [[Torah|Jewish Law]], and to the character and mission of the apostle Paul, as they appear in his letters and in Acts. | ||

| − | + | Some of the differences as to Paul's visits to Jerusalem have been explained in terms of the two authors varying interests and emphasis. The apparent discrepancy between Galatians 1-2 and Acts 15, however, is particularly problematic and is much debated. | |

| − | As for Paul as depicted in Acts, Paul claims that he was appointed the apostle to the Gentiles, as Peter was to the | + | As for Paul, character and attitude toward the Jewish Law as depicted in Acts, Paul claims in his letters that he was appointed the apostle to the Gentiles, as Peter was to "the [[circumcision]]." He also contends that circumcision and the observance of the [[Mosaic Law]] are of no importance to salvation. His words on these points in his letters are strong and decided. But in Acts, it is Peter who first opens up the way for the Gentiles. It is also Peter who uses the strongest language in regard to the intolerable burden of the Law as a means of salvation (15:10f.; cf. 1). Not a word is said of any difference of opinion between Peter and Paul at Antioch (Gal 2:11ff.). In Acts, Paul never stands forth as the unbending champion of the Gentiles. Instead, he seems continually anxious to reconcile the [[Jewish Christians]] to himself by personally observing the law of Moses. He personally circumcises [[Timothy]], whose mother is Jewish; and he willingly participates in a public vow at the [[Temple of Jerusalem|the Temple]]. He is particularly careful in his speeches to show how deep is his respect for the law of Moses. In all this, the letters of Paul are very different from Acts. |

| − | of the Law as a means of salvation (15:10f.; cf. 1) | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Speeches=== | ===Speeches=== | ||

| − | The speeches in Acts deserve special notice, because they constitute | + | The speeches in Acts deserve special notice, because they constitute a large portion of the book. Given the nature of the times, lack of recording devices, and space limitations, many ancient historians did not reproduce verbatim reports of speeches. Condensing and using one's own style was often unavoidable. There is little doubt that the speeches of Acts are summaries or condensations largely in the style and vocabulary of its author. |

| − | + | However, there are indications that the author of Acts relied on source material for his speeches, and did not always treat them as mere vehicles for expressing his own theology. The author's apparent use of speech material in the Gospel of Luke, itself obtained either from the [[Gospel of Mark]] and the hypothetical [[Q document]] or the [[Gospel of Matthew]], suggests that he relied on other sources for his narrative and was relatively faithful in using them. Additionally, many scholars have viewed Acts' presentation of Stephen's speech, Peter's speeches in Jerusalem and, most obviously, Paul's speech in [[Miletus]] as relying on source material or of expressing views not typical of the Acts' author. | |

| − | + | ==Outline== | |

| + | {{col-begin|width=95%}} | ||

| + | {{Col-break}} | ||

| + | *Dedication to [[Theophilus (Biblical)|Theophilus]] (1:1-2) | ||

| + | *[[Resurrection appearances of Jesus|Resurrection appearances]] (1:3) | ||

| + | *[[Great Commission]] (1:4-8) | ||

| + | *[[Ascension]] (1:9) | ||

| + | *[[Second Coming|Second Coming Prophecy]] (1:10-11) | ||

| + | *[[Saint Matthias|Matthias]] replaces [[Judas Iscariot|Judas]] (1:12-26) | ||

| + | *[[Holy Spirit]] at [[Pentecost]] (2) | ||

| + | *[[St. Peter|Peter]] heals a crippled beggar (3) | ||

| + | *Peter and [[John the Apostle|John]] before the [[Sanhedrin]] (4:1-22) | ||

| + | *[[Discourse on ostentation#Materialism|Everything is shared]] (4:32-37) | ||

| + | *[[Ananias and Sapphira]] (5:1-11) | ||

| + | *Signs and Wonders (5:12-16) | ||

| + | *[[Apostles]] before the Sanhedrin (5:17-42) | ||

| + | *Seven Greek Jews appointed as [[deacon]]s (6:1-7) | ||

| + | *[[Saint Stephen]] before the Sanhedrin (6:8-7:60) | ||

| + | *[[Paul of Tarsus|Saul]] persecutes the church (8:1-3) | ||

| + | {{Col-break}} | ||

| + | *[[Philip the Evangelist]] and [[Simon Magus]] (8:9-24) | ||

| + | *[[Road to Damascus|Conversion of Saul]] (9:1-31, 22:1-22, 26:9-24) | ||

| + | *Peter raises Tabitha from the dead (9:32-43) | ||

| + | *Conversion of [[Cornelius]] (10:1-8, 24-48) | ||

| + | *Peter's vision (10:9-23, 11:1-18) | ||

| + | *Church of [[Antioch]] founded (11:19-30) | ||

| + | *Peter and Herod [[Agrippa I]] (12:3-25) | ||

| + | *[[Paul_of_Tarsus#First_missionary_journey|Mission of Barnabas and Saul]] (13-14) | ||

| + | *[[Council of Jerusalem]] (15:1-35) | ||

| + | *Paul separates from Barnabas (15:36-41) | ||

| + | *[[Paul_of_Tarsus#Second_missionary_journey|2nd]] and [[Paul_of_Tarsus#Third_missionary_journey|3rd]] missions (16-20) | ||

| + | *[[Paul_of_Tarsus#Arrest_and_death|Paul in Jerusalem]] (21) | ||

| + | *Paul before the Sanhedrin (22-23) | ||

| + | *Paul in Caesaria (24-26) | ||

| + | *Trip to Rome an conclusion (27-28) | ||

| − | + | {{Col-end}} | |

| − | === | + | == Notes == |

| − | + | {{reflist}} | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==References== | |

| + | * Borgman, Paul Carlton. ''The Way According to Luke: Hearing the Whole Story of Luke-Acts.'' Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006. ISBN 978-0802829368 | ||

| + | * Carson, D. A., Moo, Douglas J. and Morris, Leon. ''An Introduction to the New Testament.'' Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005. ISBN 978-0310238591 | ||

| + | * Gallagher, Robert L., ed. ''Mission in Acts: Ancient Narratives in Contemporary Context.'' Orbis Books, 2004. ISBN 978-1570754937 | ||

| + | * Laymon, Charles M. ''The Interpreter’s One-Volume Commentary on the Bible.'' Abingdon Press, 1971. ISBN 0687192994 | ||

| + | * Mauch, John L. ''Paul On Trial: The Book Of Acts As A Defense Of Christianity.'' Thomas Nelson, 2001. ISBN 978-0785245988 | ||

| + | * Porter, Stanley E. ''Paul in Acts.'' Hendrickson Publishers, 2001. ISBN 978-1565636132 | ||

| + | * Spell, David. ''Peter and Paul in Acts.'' Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-1597527842 | ||

| + | * Wagner, Peter. ''Acts of the Holy Spirit.'' Gospel Light Publications, 2000. ISBN 978-0830720415 | ||

| − | + | ==External links== | |

| − | + | All links retrieved November 17, 2023. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * [http://bible.oremus.org/?ql=46287411 ''Acts (NRSV)'' at Oremus Bible Browser]. ''bible.oremus.org''. | |

| − | + | * [http://www.gospelhall.org/bible/bible.php?passage=acts+1 ''Online Bible'' at gospelhall.org]. ''www.gospelhall.org''. | |

| − | + | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01117a.htm Catholic Encyclopedia: Acts of the Apostles]. ''www.newadvent.org''. | |

| − | + | *[http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=245&letter=N#714 Jewish Encyclopedia: New Testament - The Acts of the Apostles]. ''jewishencyclopedia.com''. | |

| − | + | *[http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/acts_long_01_intro.htm Tertullian.org: The Western Text of the Acts of the Apostles (1923) J. M. WILSON, D.D.]. ''www.tertullian.org''. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [http://bible.oremus.org/?ql=46287411 ''Acts (NRSV)'' at Oremus Bible Browser] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [http://www.gospelhall.org/bible/bible.php?passage=acts+1 ''Online Bible'' at gospelhall.org] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/01117a.htm Catholic Encyclopedia: Acts of the Apostles] | ||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=245&letter=N#714 Jewish Encyclopedia: New Testament - The Acts of the Apostles] | ||

| − | *[http://www.tertullian.org/fathers/acts_long_01_intro.htm Tertullian.org: The Western Text of the Acts of the Apostles (1923) J. M. WILSON, D.D.] | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Books of the Bible}} |

| − | + | [[Category:Bible]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] | ||

{{Credit|133760306}} | {{Credit|133760306}} | ||

Latest revision as of 07:25, 17 November 2023

| New Testament |

|---|

The Acts of the Apostles is a book of the New Testament. It is commonly referred to as the Book of Acts or simply Acts. The title "Acts of the Apostles" (Greek Praxeis Apostolon) was first used as its title by Irenaeus of Lyon in the late second century.

Acts tells the story of the Early Christian church, with particular emphasis on the ministry of the apostles Peter and Paul of Tarsus, who are the central figures of the middle and later chapters of the book. The early chapters, set in Jerusalem, discuss Jesus' Resurrection, his Ascension, the Day of Pentecost, and the start of the apostles' ministry. The later chapters discuss Paul's conversion, his ministry, and finally his arrest, imprisonment, and trip to Rome. A major theme of the book is the expansion of the Holy Spirit's work from the Jews, centering in Jerusalem, to the Gentiles throughout the Roman Empire.

It is almost universally agreed that the author of Acts also wrote the Gospel of Luke. The traditional view is that both Luke and Acts were written in the early 60s C.E. by a companion of Paul named Luke, but many modern scholars believe these books to have been the work of an unknown author at a later date, sometime between 80 and 100 C.E. Although the objectivity of the Book of Acts has been seriously challenged, it remains, together with the letters of Paul, one of the most extensive sources on the history of the early Christian church.

Summary

Prologue

The author begins with a prologue addressed to a person named Theophilius and references "my earlier book"—almost certainly the Gospel of Luke.

This is immediately followed by a narrative in which the resurrected Jesus instructs the disciples to remain in Jerusalem to await the gift of the Holy Spirit. They ask him if he intends now to "restore the kingdom to Israel," a reference to his mission as the Jewish Messiah, but Jesus replies that the timing of such things is not for them to know (1:6-7). After this, Jesus ascends into a cloud and disappears, a scene known to Christians as the Ascension. Two "men" appear and ask why they look to the sky, since Jesus will return in the same way he went.[1]

From this point on, Jesus ceases to be a central figure in the drama of Acts, while the Holy Spirit becomes the prime actor, performing great miracles through the disciples and bringing the Gospel to all people.

The Jerusalem church

The apostles, along with Jesus' mother, his brothers,[2] and other followers, meet and elect Matthias to replace Judas Iscariot as a member of The Twelve. On Pentecost, the Holy Spirit descends on them. The apostles hear a great wind and witness "tongues of flames" descending on them. Thereafter, the apostles have the miraculous power to "speak in tongues" and when they address a crowd, each member of the crowd hears their speech in his own native language. Three thousand people reportedly become believers and are baptized as a result of this miracle (2:1-40).

Peter, along with John, preaches to many in Jerusalem, and performs miracles such as healings, the casting out of evil spirits, and the raising of the dead (ch. 3). A controversy arises due to Peter and John preaching that Jesus had been resurrected. Sadduceean priests—who, unlike the Pharisees, denied the doctrine of the resurrection—have the two apostles arrested. The High Priest, together with other Sadduceean leaders, question the two but fear punishing them on account of the recent miracle at the Temple precincts. Having earlier condemned Jesus to the Romans, the priests command the apostles not to speak in Jesus' name, but the apostles make it clear they do not intend to comply (4:1-21).

The growing community of Jewish Christians practices a form of communism: "selling their possessions and goods, they gave to anyone as he had need." (1:45) The policy is strictly enforced, and when one member, Ananias, withholds for himself part of the proceeds of a house he has sold, he and his wife are both slain by the Holy Spirit after attempting to hide their sin from Peter (5:1-20).

As their numbers increase, the believers are increasingly persecuted. Once again the Sadducees move against them. Some of the apostles are arrested again. The leader of the Pharisees, Gamaliel, however, defends them, warning his fellow members of the Sanhedrin to "Leave these men alone! Let them go! For if their purpose or activity is of human origin, it will fail. But if it is from God, you will not be able to stop these men; you will only find yourselves fighting against God." (5:38-39) Although they are flogged for disobeying the High Priest's earlier order, the disciples are freed and continue to preach openly in the Temple courtyards.

An internal controversy arises within the Jerusalem church between the Judean and Hellenistic Jews,[3] the latter alleging that their widows were being neglected. The Twelve, not wishing to oversee the distributions themselves, appointed Stephen and six other non-Judean Jews for this purpose so that the apostles themselves can concentrate on preaching (6:1-7. Many in Jerusalem soon join the faith, including "a large number of priests."

Although the apostles themselves thus manage to stay out of trouble and gain converts among the Jewish religious establishment, Stephen soon finds himself embroiled in a major controversy with other Hellenistic Jews, who accuse him of blasphemy. At his trial, Stephen gives a long, eloquent summary of providential history, but concludes by accusing those present of resisting the Holy Spirit, killing the prophets, and murdering the Messiah. This time, no one steps forward to defend the accused, and Stephen is immediately stoned to death, becoming the first Christian martyr (ch. 6-7). One of those present and approving of his death is a Pharisee named Saul of Taursus, the future Saint Paul.

As a result of Stephen's confrontation with the Temple authorities, a widespread persecution breaks out against those Jews who affirm Jesus as the Messiah. Many believers flee Jerusalem to the outlying areas of Judea and Samaria, although the apostles remain in Jerusalem. Saul is authorized by the High Priest to arrest believers and put them in prison.

The faith spreads

In Samaria, a disciple named Philip[4] performs miracles and influences many to believe. One of the new believers is Simon Magus, himself a miracle worker with a great reputation among the Samaritans. Peter and John soon arrive in order to impart the gift of the Holy Spirit—something Philip is apparently unable to do—to the newly baptized. Simon Magus is amazed at this gift and offers the apostles money that he too may learn to perform this miracle. Peter takes offense at this offer, declaring, "may your money perish with you." (8:20) Simon immediately repents and asks Peter to pray to God on his behalf. The apostles continue their journey among the Samaritans, and many believe.[5]

Philip also converts an Ethiopian eunuch, the first Gentile official reported to join the new faith (8:26-40).

Paul's conversion

Paul of Tarsus, also known as Saul, is the main character of the second half of Acts, which deals with the work of the Holy Spirit as it moves beyond Judea and begins to bring large numbers of Gentiles into faith in the Gospel. In one of the New Testament's most dramatic episodes, Paul travels on the road to Damascus, where he intends to arrest Jews who profess faith in Jesus. "Suddenly a light from heaven flashed around him. He fell to the ground" (9:3-4) and Paul becomes blind for three days (9:9). In a later account Paul hears a voice saying: "Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me? … I am Jesus" (26:14-15). In Damascus, Paul is cured from his blindness and becomes as ardent believer. The Jerusalem community is suspicious and fearful of him at first, but he wins the apostles' trust and faces danger from the Hellenistic Jews whom he debates. After this, the church in Judea, Galilee, and Samaria enjoys a period of growth and relative peace. (9:31)

Gentile converts

Peter, meanwhile, conducts several miraculous healings, including the raising of the female disciple Tabitha from the dead (9:40). During Peter's travels, a Roman centurion named Cornelius receives a revelation from an angel that he must meet Peter.[6] Cornelius sends an invite Peter to dine with him. Peter himself, meanwhile, has a dream in which God commands him to eat non-kosher food, which Peter has never done previously (ch. ten). The next day, Peter eats at Cornelius' home and preaches there. Several Gentiles are converted, and Peter baptizes them.[7] Back in Jerusalem, Peter is criticized by the "circumcised believers" for entering a Gentile home and eating with non-Jews. His critics are silenced, however, when Peter relates the above events.[8]

Soon a sizable group of Gentile believers has joined the faith in Syrian Antioch, the Roman Empire's third largest city. The Jerusalem church sends Barnabas, a Levite, to minister to them.[9]Barnabas finds Paul in Tarsus and brings him to Antioch to assist in the mission. It is here that the followers of Jesus are first called Christians. Christian prophets, one of whom is named Agabus, come to Antioch from Jerusalem and predict to the Anitochans that a famine will soon spread across the Roman world. A collection is taken up to send aid to the Judean church.

Peter, meanwhile, is imprisoned by King Herod Agrippa,[10] but miraculously escapes. Agrippa himself is soon slain by an angel after allowing himself to be honored instead of God (ch. 12).

Probably several years later, Barnabas and Paul set out on a mission to further spread the faith (13-14). They travel first to Selucia and Cyprus, and then to Asia Minor, preaching in synagogues and visiting existing Christian congregations throughout the region. They have many adventures, often running afoul of Jewish leaders.[11]In Lystra, after a miracle of healing, the local Gentile community hails Barnabas as Zeus and Paul as Hermes, titles they, of course, reject. They establish local churches and appoint leaders to guide them, finally returning to Antioch for a long stay.

The council of Jerusalem

At Antioch, a controversy arises when members from Jerusalem arrive and insist that Gentile believers must be circumcised (15:1). Paul and Barnabas then travel to Jerusalem and consult with the apostles—a meeting known as the Council of Jerusalem (15). Paul's own record of the meeting is apparently recorded in Galatians 2.[12] Some members of the Jerusalem church are strict Pharisees and hold that circumcision is required for Gentiles who join the faith. Paul and his associates strongly disagree.

After much debate, James, the brother of Jesus and leader of the Jerusalem church, decrees that Gentile members need not follow all of the Mosaic Law, and in particular, they do not need to be circumcised. Paul's party, however, is required to accept that Gentiles must obey the commandments against eating food sacrificed to idols, meat that is not fully cooked, and meat of strangled animals, as well as from sexual immorality.[13] (15:29)

Paul and Barnabas part ways

Paul and Barnabas now plan a second missionary journey. However, they have a falling out over whether John Mark should accompany them, Paul objecting on the grounds that he had deserted them during their first journey and returned to Jerusalem.[14] Paul continues on without Barnabas or Mark, who are not heard from again. Paul takes Silas with him and goes to Derbe and then Lystra, where they are joined by Timothy, the son of a Jewish woman and a Greek man. According to Acts 16:3, Paul circumcises Timothy before continuing his journey, in order to satisfy the objections of conservative Jews.[15]

Paul spends the next several years traveling through western Asia Minor and founds the first Christian church in Philippi. He then travels to Thessalonica, where he stays for some time before departing for Greece. In Athens, he visits an altar with an inscription dedicated to the Unknown God, and when he gives his speech on the Areopagos, he declares that he worships that same Unknown God, which he identifies as the Christian God. In Corinth, he settles for more than a year but faces charges that he was "persuading the people to worship God in ways contrary to the law." (18:12–17) Typically, Paul begins his stay in each city by preaching in the synagogues, where he finds some sympathetic hearers but also provokes stiff opposition. At Ephesus, he gains popularity among the Gentiles, and a riot breaks out as idol-makers fear that Paul's preaching will harm their business, associated with the Temple of Artemis, one of the Seven Wonders of the World (ch. 19).

During these travels, Paul not only founds and strengthens several churches; he also collects funds for a major donation he intends to bring to Jerusalem.[16] His return is delayed by shipwrecks and close calls with the authorities, but finally he lands in Tyre, where he is warned by the Holy Spirit not to continue on to Jerusalem. Likewise in Caesarea, Paul is warned by the prophet Agabus that he will be arrested if he goes to the Holy City. Paul stubbornly refuses to be dissuaded, however.

Paul trials and final journey

Upon Paul's arrival in Jerusalem, he is met by James, who confronts him with the rumor that he is teaching against the Law of Moses:

"You see, brother, how many thousands of Jews have believed, and all of them are zealous for the law. They have been informed that you teach all the Jews who live among the Gentiles to turn away from Moses, telling them not to circumcise their children or live according to our customs. What shall we do?" (21:20-22)

To prove that he himself is "living in obedience to the law," Paul accompanies some fellow Jewish Christians who are completing a vow at the Temple (21:26) and pays the necessary fees for them. Paul is recognized, however, and he is nearly beaten to death by a mob, accused of the sin of bringing Gentiles into the Temple confines (21:28). Paul is rescued from being flogged when he informs a Roman commander that he is a citizen of Rome.

Paul is then brought before the Sanhedrin. He runs afoul of the Sadduceean High Priest, but cleverly plays to his fellow Pharisees on the council by claiming that the real issue at stake is the doctrine of the resurrection of the dead (23:6). Paul wins a temporary reprieve but is imprisoned in Caesarea after a plot against his life is uncovered. There, before the Roman governor Felix, Paul is confronted again by the High Priest, and once again Paul insists that, although he is indeed following of "The Way," the real reason he is being accused by the Sadducees is that he believes in the doctrine of the resurrection, as do most Pharisees. Paul remains imprisoned in Caesaria for two years. He later preaches before Agrippa II and is finally sent by sea to Rome, where he spends another two years under house arrest (28:30-31). From there he writes some of his most important letters.

The Book of Acts does not record the outcome of Paul's legal troubles. It concludes:

For two whole years Paul stayed there in his own rented house and welcomed all who came to see him. Boldly and without hindrance he preached the kingdom of God and taught about the Lord Jesus Christ.

Themes and style

Salvation to the Gentiles

One of the central themes of Acts is the idea that Jesus' teachings were for all humanity—Jews and Gentiles alike. Christianity is presented as a religion in its own right, rather than a sect of Judaism. Whereas the Jewish Christians were circumcised and adhered to the kosher dietary laws, the Pauline Christianity featured in Acts did not require Gentiles to be circumcised; and its list of Mosaic commandments required for Gentiles was limited to a small number. Acts presents the movement of the Holy Spirit first among the Jews of Jerusalem in the opening chapters, then to the Gentiles and Jews alike in the middle chapters, and finally to the Gentiles primarily in the end. Indeed, the final statement of Paul in Acts can be seen as the basic message of the Book of Acts itself: "I want you to know that God's salvation has been sent to the Gentiles, and they will listen!" (28:28)

The Holy Spirit

As in the Gospel of Luke, there are numerous references to the Holy Spirit throughout Acts. The book uniquely features the "baptism in the Holy Spirit" on Pentecost and the subsequent spirit-inspired speaking in tongues (1:5, 8; 2:1-4; 11:15-16). The Holy Spirit is shown guiding the decisions and actions of Christian leaders (15:28; 16:6-7; 19:21; 20:22-23) and the Holy Spirit is said to "fill" the apostles, especially when they preach (1:8; 2:4; 4:8, 31; 11:24; 13:9, 52).

Concern for the oppressed

The Gospel of Luke and Acts both devote a great deal of attention to the oppressed and downtrodden. In Luke's Gospel, the impoverished are generally praised (Luke 4:18; 6:20–21) while the wealthy are criticized. Luke alone tells the parable of the Good Samaritan, while in Acts a large number of Samaritans join the church (Acts 8:4-25) after the Jerusalem authorities launch a campaign to persecute those who believe in Jesus. In Acts, attention is given to the suffering of the early Christians, as in the case of Stephen's martyrdom, Peter's imprisonments, and Paul's many sufferings for his preaching of Christianity.

Prayer and speeches

Prayer, too, is a major motif in both the Gospel of Luke and Acts. Both books have a more prominent attention to prayer than is found in the other gospels.

Acts is also noted for a number of extended speeches and sermons from Peter, Paul, and others. There are at least 24 such speeches in Acts, comprising about 30 percent of the total verses.[17]

The "Acts" genre

The word "Acts" (Greek praxeis) denotes a recognized genre in the ancient world, "characterizing books that described great deeds of people or of cities."[18] Many ancient works also tell marvelous tales of travels to foreign places, and Acts fits with this type as well, complete with stories of shipwrecks, escapes from prison, miraculous healings and slayings, interventions by angelic beings, descriptions of famous foreign buildings, and dramatic close encounters with both mobs and legal authorities.

There are several such books in the New Testament apocrypha, including the Acts of Thomas, the Acts of Paul (and Thecla), the Acts of Andrew, and the Acts of John.

Authorship

While the precise identity of the author is debated, the consensus of scholarship holds that the author was an educated Greek Gentile man writing for an audience of Gentile Christians. There is also substantial evidence to indicate that the author of the Book of Acts also wrote the Gospel of Luke. The most direct evidence comes from the prefaces of each book, both of which are addressed to Theophilus, probably the author's patron. Furthermore, the preface of Acts explicitly references "my former book" about the life of Jesus—almost certainly the work we know as the Gospel of Luke.

There are also clear linguistic and theological similarities between the Luke and Acts. Because of their common authorship, the Gospel of Luke and Acts of the Apostles are often jointly referred to as Luke-Acts.

Luke the physician

The traditional view is that the Book of Acts was written by the physician Luke, a companion of Paul. This Luke is mentioned in Paul's Epistle to Philemon (v.24), and in two other epistles which are traditionally ascribed to Paul (Colossians 4:14 and 2 Timothy 4:11).

The view that Luke-Acts was written by the physician Luke was nearly unanimous among the early Church Fathers who commented on these works. The text of Luke-Acts provides important hints that its author was either himself a companion of Paul, or that he used sources from one of Paul's companions. The so-called "'we passages" are often cited as evidence of this. Although the bulk of Acts is written in the third person, several brief sections are written from a first-person plural perspective.[19] For example: "After Paul had seen the vision, we got ready at once to leave for Macedonia… we put out to sea and sailed straight for Samothrace." (16:10-11) It has also been argued that the level of detail used in the narrative describing Paul's travels suggests an eyewitness source. Some claim that the vocabulary used in Luke-Acts suggests its author may have had medical training.

Others believe that Acts was written by an anonymous Christian author who may not have been an eyewitness to any of the events recorded within the text. In the preface to Luke, the author refers to having eyewitness testimony "handed down to us" and to having undertaken a "careful investigation," but the author does not claim to be an eyewitness to any of the events. Except for the "we" passages in Acts, the narrative of Luke-Acts is written in the third person, and the author never refers to himself as "I" or "me." The "we passages" are thus regarded as fragments of a source document which was later incorporated into Acts by the author.

Scholars also point to a number of apparent theological and factual discrepancies between Luke-Acts and Paul's letters. For example, Acts and the Pauline letters appear to disagree about the number and timings of Paul's visits to Jerusalem, and Paul's own account of his conversion is different from the account given in Acts. Similarly, some believe the theology of Luke-Acts is also different from the theology espoused by Paul in his letters. Acts moderates Paul's opposition to circumcision and the kosher dietary laws, and it downplays bitter disagreements between Paul and Peter, and Paul and Barnabas. To some, this suggests that the author of Luke-Acts did not have significant contact with Paul, but instead relied on other sources for his portrayal of Paul.

Sources

The author of Acts likely relied upon written sources, as well as oral tradition, in constructing his account of the early church and Paul's ministry. Evidence of this is found in the prologue to the Gospel of Luke, where the author alluded to his sources by writing, "Many have undertaken to draw up an account of the things that have been fulfilled among us, just as they were handed down to us by those who from the first were eyewitnesses and servants of the word."

It is generally believed that the author of Acts did not have access to a collection of Paul's letters. One piece of evidence suggesting this is, that although half of Acts centers on Paul, Acts never directly quotes from the epistles nor does it even mention Paul writing letters. Additionally, the epistles and Acts disagree about the chronology of Paul's career.

Date

Conservative Christian scholars often date the Book of Acts quite early. For example, Norman Geisler believes it was written between 60-62 C.E.[20] Others have suggested that Acts was written as a defense of Paul for his upcoming trial in Rome.[21]. Arguing for an early date is the fact that Paul has not yet died when the book ends, nor is there any reference to Jewish rebellion against Rome and the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, which took place in 70 C.E.

However, Acts 20:25 suggests that the author knows of Paul's death: "I know that none of you.. will ever see me again." Moreover many scholars believe that Luke did have knowledge of the Temple's destruction (Luke 19:44; 21:20), and that his Gospel was written during the reign of Emperor Domitian (81-96). One of Luke's purposes in writing to Theophilus, possibly a Roman official whom he addresses as "excellency," may have been to demonstrate that the Christians were loyal to Rome, unlike many Jews. The fact that Acts shows no awareness of Paul's letters means that Luke probably wrote before Paul's epistles were collected and distributed. Thus, liberal scholarship tends to put the date of Acts at somewhere between 85 and 100 C.E.[22]

The place of composition is still an open question. For some time Rome and Antioch have been in favor, but some believe internal evidence points to the Roman province of Asia, particularly the neighborhood of Ephesus.

Historicity

The question of authorship of Acts is largely bound up with that of the historicity of its contents. Conservative scholars view the book as being basically accurate while skeptics view it as historically unreliable, its purpose being basically propagandistic and faith-driven.

Beyond these basic differences in attitude, faithful Christians as well as secular scholars have devoted much effort to discussing the accuracy of Acts. It is one of the few Christian documents that can be checked in many details against other known contemporary sources, namely the letters of Paul, one of Acts' own main characters.

Acts. vs. Paul's epistles

Attention has been drawn particularly to the account given by Paul of his visits to Jerusalem in Galatians as compared with Acts, to the account of Paul's conversion, his attitude toward the Jewish Law, and to the character and mission of the apostle Paul, as they appear in his letters and in Acts.

Some of the differences as to Paul's visits to Jerusalem have been explained in terms of the two authors varying interests and emphasis. The apparent discrepancy between Galatians 1-2 and Acts 15, however, is particularly problematic and is much debated.

As for Paul, character and attitude toward the Jewish Law as depicted in Acts, Paul claims in his letters that he was appointed the apostle to the Gentiles, as Peter was to "the circumcision." He also contends that circumcision and the observance of the Mosaic Law are of no importance to salvation. His words on these points in his letters are strong and decided. But in Acts, it is Peter who first opens up the way for the Gentiles. It is also Peter who uses the strongest language in regard to the intolerable burden of the Law as a means of salvation (15:10f.; cf. 1). Not a word is said of any difference of opinion between Peter and Paul at Antioch (Gal 2:11ff.). In Acts, Paul never stands forth as the unbending champion of the Gentiles. Instead, he seems continually anxious to reconcile the Jewish Christians to himself by personally observing the law of Moses. He personally circumcises Timothy, whose mother is Jewish; and he willingly participates in a public vow at the the Temple. He is particularly careful in his speeches to show how deep is his respect for the law of Moses. In all this, the letters of Paul are very different from Acts.

Speeches

The speeches in Acts deserve special notice, because they constitute a large portion of the book. Given the nature of the times, lack of recording devices, and space limitations, many ancient historians did not reproduce verbatim reports of speeches. Condensing and using one's own style was often unavoidable. There is little doubt that the speeches of Acts are summaries or condensations largely in the style and vocabulary of its author.

However, there are indications that the author of Acts relied on source material for his speeches, and did not always treat them as mere vehicles for expressing his own theology. The author's apparent use of speech material in the Gospel of Luke, itself obtained either from the Gospel of Mark and the hypothetical Q document or the Gospel of Matthew, suggests that he relied on other sources for his narrative and was relatively faithful in using them. Additionally, many scholars have viewed Acts' presentation of Stephen's speech, Peter's speeches in Jerusalem and, most obviously, Paul's speech in Miletus as relying on source material or of expressing views not typical of the Acts' author.

Outline

|

|

Notes

- ↑ Some believe this refers to his second coming on the clouds, while others hold that, since the disciples are told not to look to the sky for his return, the second coming will not occur on the clouds.

- ↑ Catholic tradition, which affirms Mary's perpetual virginity, denies that these "brothers" are Mary's sons, interpreting them to be either cousins or Joseph's sons by a previous marriage.

- ↑ Hellenistic Jews, here, were apparently those whose origins were in the diaspora and were less connected to the Jerusalem tradition of the early believers in Jesus

- ↑ This is not the apostle, since they have stayed in Jerusalem. Later he is identified as one of the "seven," a deacon, like Stephen.

- ↑ In later tradition, Simon is thought to be the first of the Gnostic heretics. The term "simony"—the buying of ecclesiastical office—is derived from his name.

- ↑ Although he is a Gentile, Cornelius is already a believer in the God of the Jews. These "God-fearers" would become a primary audience of Christian preaching, which promised them salvation without having to be circumcised or following all of the Mosaic laws.

- ↑ The fact that these men are baptized into the faith without first being circumcised is significant in showing that not only Paul, but Peter, too, practiced this tradition.

- ↑ Many scholars believe these chapters are related to the incident in Galatians 3, in which Paul criticizes Peter for refusing to eat with Gentiles. Some hold that the incidents of chapter ten are misplaced in the narrative, while others believe them to be fictional.

- ↑ As a Levite, Barnabas would be particularly knowledgeable about Jewish tradition. He is thus an interesting choice as Jerusalem's representative to the first Christian community composed largely of Gentiles.

- ↑ "Kings" such as Agrippa ruled by the consent of Rome and were often perceived as Roman agents by local populations such as the Jews.

- ↑ One reason for this persecution is that Paul often addresses the "Gentiles who worship God" in the synagogues, offering them complete membership in the new faith without circumcision or having to adhere to the entire Mosaic Law. In the synagogues, such "God-fearers" (and their financial support) were welcome, but they could not attain full membership without circumcision.

- ↑ However, the account differs significantly from Acts, and some argue Gal. 2 is a different meeting.

- ↑ Paul's own letters call into question whether he would have agreed with these stipulations, for he often argues that obedience to dietary laws is not necessary at all for Gentiles. He also says in 1 Corinthians 8 that idols are not really gods, so only those with weak consciences are harmed by this action; but it is still good practice to refrain from eating such meat publicly, because those who think idols are indeed gods should not be led to think that Christians are honoring this false gods. This policy leaves the true believer free to eat such meats in private, and since much meat was ritually slaughtered by pagan butchers, this would likely be a frequent practice.

- ↑ Some believe that the true nature of Paul's split with Barnabas was over the question of table fellowship with Gentiles, mentioned in Galatians 3. Others add that Paul may have believed Mark to be a spy whose loyalties were with the conservative elements of the Jerusalem church.

- ↑ Considering Paul's views on circumcision in his letter to the Galatians, such an act constitutes a major concession by Paul. Some scholars consider the episode a fiction.

- ↑ The theme of Paul's uneasy relations with Jerusalem runs just beneath the surface of Acts, leading many to believe his donation is, in effect, an attempt to show both his good will and his value, despite his controversial teachings.

- ↑ Fictitious Speeches in Acts. www.geocities.com. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ↑ D. A. Carson, Douglas J. Moo, and Leon Morris. An Introduction to the New Testament. (Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005), 181.

- ↑ Acts 16:10–17, 20:5–15, 21:1–18, and 27:1–28:16

- ↑ Dating of the New Testament, Dr. Norman Geisler www.bethinking.org. Retrieved August 6, 2007.

- ↑ John L. Mauch. Paul On Trial: The Book Of Acts As A Defense Of Christianity. (Thomas Nelson, 2001)

- ↑ See for example William Baird, "Acts of the Apostles," in the Interpreters Bible, 1971.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Borgman, Paul Carlton. The Way According to Luke: Hearing the Whole Story of Luke-Acts. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2006. ISBN 978-0802829368

- Carson, D. A., Moo, Douglas J. and Morris, Leon. An Introduction to the New Testament. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, 2005. ISBN 978-0310238591

- Gallagher, Robert L., ed. Mission in Acts: Ancient Narratives in Contemporary Context. Orbis Books, 2004. ISBN 978-1570754937

- Laymon, Charles M. The Interpreter’s One-Volume Commentary on the Bible. Abingdon Press, 1971. ISBN 0687192994

- Mauch, John L. Paul On Trial: The Book Of Acts As A Defense Of Christianity. Thomas Nelson, 2001. ISBN 978-0785245988

- Porter, Stanley E. Paul in Acts. Hendrickson Publishers, 2001. ISBN 978-1565636132

- Spell, David. Peter and Paul in Acts. Wipf & Stock Publishers, 2006. ISBN 978-1597527842

- Wagner, Peter. Acts of the Holy Spirit. Gospel Light Publications, 2000. ISBN 978-0830720415

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2023.

- Acts (NRSV) at Oremus Bible Browser. bible.oremus.org.

- Online Bible at gospelhall.org. www.gospelhall.org.

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Acts of the Apostles. www.newadvent.org.

- Jewish Encyclopedia: New Testament - The Acts of the Apostles. jewishencyclopedia.com.

- Tertullian.org: The Western Text of the Acts of the Apostles (1923) J. M. WILSON, D.D.. www.tertullian.org.

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here: