Jerusalem

| Jerusalem ◊ô÷į◊®◊ē÷ľ◊©÷ł◊Ā◊ú÷∑◊ô÷ī◊Ě (Yerushalayim) ōßŔĄŔāŔŹōĮō≥ (al-Quds) |

|||

| ‚ÄĒ¬†¬†City¬†¬†‚ÄĒ | |||

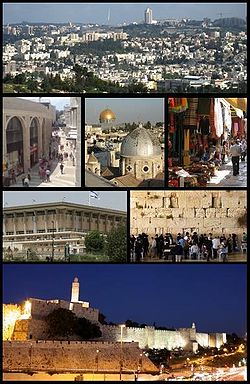

| From upper left: Jerusalem skyline viewed from Givat ha'Arba, Mamilla, the Old City and the Dome of the Rock, a souq in the Old City, the Knesset, the Western Wall, the Tower of David and the Old City walls | |||

|

|||

| Nickname: Ir ha-Kodesh (Holy City), Bayt al-Maqdis (House of the Holiness) | |||

| Coordinates: 31¬į47‚Ä≤N 35¬į13‚Ä≤E | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| District | Jerusalem | ||

| Government | |||

|  - Mayor | Nir Barkat | ||

| Area | |||

|  - City | 125 km² (48.3 sq mi) | ||

|  - Metro | 652 km² (251.7 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 754 m (2,474 ft) | ||

| Population (2017) | |||

|  - City | 901,302 | ||

|  - Density | 7,200/km² (18,647.9/sq mi) | ||

|  - Metro | 12,539,000 | ||

| Area code(s) | overseas dialing +972-2; local dialing 02 | ||

| Website: jerusalem.muni.il | |||

Jerusalem (Hebrew: ◊ô÷į◊®◊ē÷ľ◊©◊Ā÷ł◊ú÷∑◊ô÷ī◊Ě Yerushalayim; Arabic: ōßŔĄŔāōĮō≥ al-Quds) is an ancient Middle Eastern city of key importance to the religions of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Perhaps no city on earth binds the hearts of believers in so complete a way. Today Jerusalem is the capital of Israel and the home of its legislature, the Knesset, although that designation is disputed in international circles. Jerusalem is a city of diverse neighborhoods, from the ancient walled Old City to the modern districts of West Jerusalem, and from the Arab sections of East Jerusalem to the Orthodox Jewish neighborhoods of Mea She'arim. It is also a stunningly beautiful city, where by law all buildings are faced with white limestone that sets off the golden Dome of the Rock that is thought to stand on the site of the ancient Jerusalem Temple.

From 1948 until the Six-Day War of 1967, Jerusalem was a divided city, with Jordan controlling East Jerusalem and the Old City while Israel governed West Jerusalem. Skirmishes were frequent across the Green Line, and Jews were not permitted access to the Western Wall, their most important holy site. The Six-Day War resulted in a unified city under Israeli rule. The Jerusalem city government has tried to balance the needs of these various constituencies in the unified city, and also maintain each community's security and access to their respective holy places. Today the future of a unified Jerusalem faces challenges‚ÄĒtensions arising from the wall of separation that now severs some Palestinian neighborhoods from the city, and from the construction of substantial Jewish suburbs such as the Israeli settlement of Ma'ale Adumim within the disputed West Bank.

Nevertheless, in the hearts of believers all over the world, Jerusalem remains the city of peace. They regard its holy places as the center of the most far-reaching participation of the divine in human affairs. Poetry abounds for the city, as though for a lover, one poet writes in voice of God:

Only be it known it's you I have married

Come back to Me, come back to Me

My Bride ‚Äď Jerusalem!

The history of the city, and the on-going passion of believers, continues to make the city central in human affairs today.

Name

The origin of the city name is uncertain. It is possible to understand the name (Hebrew Yerushalayim) as either "Heritage of Salem" or "Heritage of Peace"‚ÄĒa contraction of "heritage" (yerusha) and Salem (Shalem literally "whole" or "complete") or "peace" (shalom). (See the biblical commentator the Ramban for explanation.) "Salem" is the original name used in Genesis 14:18 for the city.

Geography

Jerusalem is situated at 31¬į 46‚Ä≤ 45‚Ä≥ N 35¬į 13‚Ä≤ 25‚Ä≥ on the southern spur of a plateau, the eastern side of which slopes from 2,460 feet above sea-level north of the Temple area to 2,130 feet at its southeastern-most point. The western hill is about 2,500 feet high and slopes southeast from the Judean plateau.

Jerusalem is surrounded upon all sides by valleys, of which those on the north are least pronounced. The two principal valleys start northwest of the present city. The first runs eastward with a slight southerly bend (the present Wadi al-Joz), then, turns directly south (formerly known as "Kidron Valley," the modern Wadi Sitti Maryam), dividing the Mount of Olives from the city. The second runs directly south on the western side of the city. It then turns eastward at its southeastern extremity, to run due east eventually joining the first valley near Bir Ayyub ("Job's Well"). In early times it was called the "Valley of Hinnom," and in modern times is the Wadi al-Rababi (not to be confused with the first-mentioned valley).

A third valley starts in the northwest where the Damascus Gate is now located, and runs south-southeast to the Pool of Siloam. It divides at the lower part into two hills, the lower and the upper cities of Josephus. A fourth valley proceeds from the western hill (near the present Jaffa Gate) toward the Temple area, existing in modern Jerusalem as David Street. A fifth valley cuts the eastern hill into the northern and southern parts of the city. Later, Jerusalem came to be built on these four spurs. Today, neighboring towns are Bethlehem and Beit Jala at the southern city border, and Abu Dis to the east.

History

Antiquity

Since Jerusalem is hotly contested at present, historical inquiry into the city's origins has become politicized.

According to Jewish tradition Jerusalem was founded by Abraham's forefathers Shem and Eber. Genesis reports that the city was ruled by Melchizedek, regarded in Jewish tradition as being a priest of God and identical to Shem. Later it was conquered by the Jebusites before returning to Jewish control. The Bible records that King David defeated the Jebusites in war and captured the city without destroying it. David then expanded the city to the south, and declared it the capital city of the united Kingdom of Israel.

Later, according to the Bible, the First Jewish Temple was built in Jerusalem by King Solomon. The Temple became a major cultural center in the region, eventually overcoming other ritual centers such as Shiloh and Bethel. By the end of the "First Temple Period," Jerusalem was the sole-acting religious shrine in the kingdom and a center of regular pilgrimage. It was at this time that historical records begin to corroborate biblical history. The kings of Judah are historically identifiable.

Near the end of King Solomon's reign, the northern ten tribes separated, and formed the Kingdom of Israel with its capital at Samaria. Jerusalem remained as the capital of the southern Kingdom of Judah.

Jerusalem continued as the capital of the Kingdom of Judah for some 400 years. It had survived (or, as some historians claim, averted) an Assyrian siege in 701 B.C.E., unlike the northern capital, Samaria, which had fallen some twenty years prior.

In 586 B.C.E., however, the city was overcome by the Babylonians who took the king Jehoiachin and most of the aristocracy into Babylonian captivity. Nebuchadrezzar II captured and destroyed the city, burnt the temple, ruined the city walls, and left the city unprotected.

After several decades, Persians conquered Babylon and allowed the Jews to return to Judah where they rebuilt the city walls and restored the Temple. It continued as the capital of Judah, a province under the Persians, Greeks, and Romans, enjoying only a short period of independence. The Temple (known as the Second Temple) was rebuilt, and the Temple complex was upgraded under Herod the Great.

First millennium

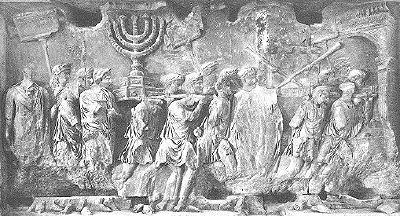

Internal strife and an uprising against Rome, resulted in the sack and ruin of Jerusalem at the hands of Roman leader Titus Flavius in 70 C.E.

Jerusalem was destroyed and the Second Temple burnt. All that remained was a portion of an external (retaining) wall, which became known as the Western Wall.

Sixty years later, after crushing the Bar Kokhba's revolt, the Roman emperor Hadrian resettled the city as a pagan polis under the name Aelia Capitolina. Jews were forbidden to enter the city, but for a single day of the year, Tisha B'Av, (the Ninth of Av), when they could weep for the destruction of their city at the Temple's only remaining wall.

Under the Byzantines, who cherished the city for its Christian history, in accordance with traditions of religious tolerance often found in the ancient East, Jews could return to the city in the fifth century.

Although the Qur'an does not mention the name "Jerusalem," the hadiths hold that it was from Jerusalem that the Prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven in the Night Journey, or Isra and Miraj.

In 638 C.E., Jerusalem was one of the Arab Caliphate's first conquests. According to Arab historians of the time, the Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab personally went to the city to receive its submission, praying at the Temple Mount in the process. Some Muslim and non-Muslim sources add that he built a mosque there. Sixty years later, the Dome of the Rock was built, a structure in which lies the stone on which Muhammad is said to have tethered his mount Buraq during the Isra. This is also reputed to be the place where Abraham went to sacrifice his son (Isaac in the Jewish tradition, Ishmael in the Muslim one). Note that the octagonal and gold-sheeted Dome is not the same as the Al-Aqsa Mosque beside it, which was built more than three centuries later.

Under the early centuries of Muslim rule, the city prospered; the geographers Ibn Hawqal and al-Istakhri (tenth century) describe it as "the most fertile province of Palestine," while its native son the geographer al-Muqaddasi (born 946) devoted many pages to its praises in his most famous work, The Best Divisions in the Knowledge of the Climes.

Second millennium

The early Arab period was one of religious tolerance, but in the eleventh century, the Egyptian Fatimid Caliph Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah ordered the destruction of all churches and synagogues in Jerusalem. This policy was reversed by his successors, but reports of this edict were a major cause for the First Crusade. Europeans captured Jerusalem after a difficult one month siege, on July 15, 1099. The siege and its aftermath are known to be extreme in the loss of life both during and after the siege.

From this point, Jerusalem became the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, a feudal state, headed by the King of Jerusalem. Neither Jews nor Muslims were allowed into the city during that time. This kingdom lasted until 1291, though Jerusalem itself was recaptured by Saladin in 1187. Under Saladin, all worshipers were once again welcomed to the city.

In 1219 the walls of the city were taken down by order of the Sultan of Damascus; in 1229, by treaty with Egypt, Jerusalem came into the hands of Frederick II of Germany. In 1239, he began to rebuild the walls; but they were again demolished by Da'ud, the emir of Kerak.

In 1243, Jerusalem again came under Christian rule, and the walls were repaired. The Kharezmian Tatars took the city in 1244; they, in turn, were driven out by the Egyptians in 1247. In 1260, the Tatars under Hulaku Khan overran the whole land, and the Jews that were in Jerusalem had to flee to the neighboring villages.

In 1244, Sultan Malik al-Muattam razed the city walls, rendering it again defenseless and dealing a heavy blow to the city's status. In the middle of the thirteenth century, Jerusalem was captured by the Egyptian Mamluks.

In 1517, it was taken over by the Ottoman Empire and enjoyed a period of renewal and peace under Suleiman the Magnificent. The walls of what is now known as the Old City were built at this time. The rule of Suleiman and the following Ottoman Sultans are described by some as an age of "religious peace"; Jews, Christians, and Muslims enjoyed the form of religious freedom interpreted in Muslim law. At this time, it was possible to find synagogue, church, and mosque on the same street. The city remained open to all religions according to Muslim law. Economic stagnation, however, characterized the region after the rule of Suleiman.

Nineteenth and early twentieth century

The modern history of Jerusalem is said to begin in the mid-nineteenth century, with the decline of the Ottoman Empire. At that time, the city was small and by some measures insignificant, with a population that did not exceed 8,000.

It was still a very heterogeneous city because of its significance to Jews, Christians, and Muslims.

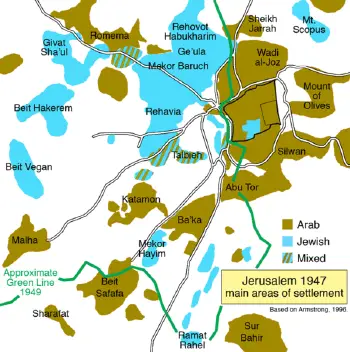

Inhabitants were divided into four major communities; Jewish, Christian, Muslim, and Armenian. The first three were further divided into numerous subgroups based on more precise subdivisions of their religious affiliation or country of origin.

This division into these communities is clearly seen in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, which was partitioned meticulously among the Greek Orthodox, Catholic, Armenian, Coptic, and Ethiopian churches. Each group was given a different, little section of the sanctuary, and tensions between the groups ran so deep that the keys to the shrine were kept with a ‚Äúneutral‚ÄĚ Muslim family for safekeeping.

Each community was located around its respective shrine. The Muslim community, then the largest, surrounded the Haram ash-Sharif or Temple Mount (northeast), the Christians lived mainly in the vicinity of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre (northwest), the Jews lived mostly on the slope above the Western Wall (southeast), and the Armenians lived near the Zion Gate (southwest). These weren't total and exclusive. Nevertheless, these came to form the basis of the four quarters established during the British Mandate period (1917‚Äď1948).

Several changes occurred in the mid-nineteenth century, which had long-lasting effects on the city. The implications of these changes can be felt today and many lie at the root of the present and ongoing Palestinian-Israel conflict over Jerusalem.

The first of these was a trickle of Jewish immigrants, from the Middle East and eastern Europe, which shifted the balance of population. The first such immigrants were Orthodox Jews: some were elderly individuals, who came to die in Jerusalem and be buried on the Mount of Olives; others were students, who came with their families to await the coming of the Messiah. At the same time, European colonial powers also began seeking toeholds in the city, hoping to expand their influence pending the imminent collapse of the Ottoman Empire. This was also an age of Christian religious revival, and many churches sent missionaries to proselytize among the Muslim, and especially, the Jewish populations, believing that this would speed the Second Coming of Christ. Finally, the combination of European colonialism and religious zeal was expressed in a new scientific interest in the biblical lands in general and Jerusalem in particular. Archeological and other expeditions made some spectacular finds, which increased interest in Jerusalem even more.

By the 1860s, the city, with an area of only 1 square kilometer, was already overcrowded, leading to the construction of the New City, the part of Jerusalem outside of the city walls. Seeking new areas to stake their claims, the Russian Orthodox Church began constructing a complex, now known as the Russian Compound, a few hundred meters from Jaffa Gate. The first attempt at residential settlement outside the walls of Jerusalem was begun by Jews, who built a small complex on the hill overlooking Zion Gate, across the Valley of Hinnom. This settlement, known as Mishkenot Shaananim, eventually flourished and set the precedent for other new communities to spring up to the west and north of the Old City. In time, as the communities grew and connected geographically, this became known as the New City.

British conquest

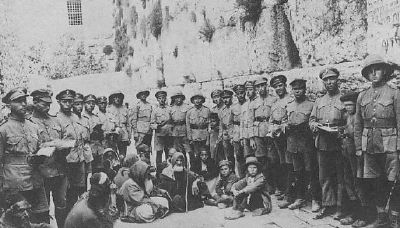

Eventually, the British conquered the Turks in the Middle East and Palestine. On December 11, 1917, General Sir Edmund Allenby, commander-in-chief of the Egyptian Expeditionary Force, entered Jerusalem on foot out of respect for the Holy City.

By the time General Allenby took Jerusalem from the Ottomans in 1917, the new city was a patchwork of neighborhoods and communities, each with a distinct ethnic character.

This circumstance continued under British rule. The neighborhoods tended to flourish, leaving the Old City of Jerusalem to slide into little more than an impoverished older neighborhood. One of the British bequests to the city was a town planning order requiring new buildings in the city to be faced with sandstone and thus preserving some of the overall look of the city.

The Status Quo

From the seventeenth to the nineteenth century, various Catholic European nations petitioned the Ottoman Empire for Catholic control of the ‚Äúholy places.‚ÄĚ The Franciscans traditionally were the Catholic custodians of the holy sites. Control of these sites changed back and forth between the Western and Eastern churches throughout this period. Sultan Abd-ul-Mejid I (1839‚Äď1861), perhaps out of frustration, published a firman that laid out in detail the exact rights and responsibility of each community at the Holy Sepulchre. This document became known as the Status Quo, and is still the basis for the complex protocol of the shrine. The Status Quo was upheld by the British Mandate and Jordan. After the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, and the passing of the Old City into Israeli hands, the Knesset passed a law protecting the holy places. Five Christian communities currently have rights in the Holy Sepulchre: the Greek Patriarchate, Latins (Western Rite Roman Catholics), Armenians, Copts, and Syriac Orthodox.

Six-Day War aftermath

East Jerusalem was captured by the Israel Defense Force following the Six-Day War in 1967. Most Jews celebrated the event as a liberation of the city; a new Israeli holiday was created, Jerusalem Day (Yom Yerushalayim), and the most popular secular Hebrew song, "Jerusalem of Gold" (Yerushalayim shel zahav), was written in celebration. Following this, the medieval Magharba Quarter was demolished, and a huge public plaza was built in its place behind the Western Wall.

Current status

Presently, the status of the city is disputed.

Israeli law designates Jerusalem as the capital of Israel; only a few countries recognize this designation.

Additionally, Israeli Jerusalem Law regards Jerusalem as the capital of the State of Israel, and as the center of Jerusalem District; it serves as the country's seat of government and otherwise functions as capital. Countries that do not recognize Israeli sovereignty over some or all of the city maintain their embassies in Tel Aviv or in the suburbs.

The 1947 UN Partition Plan states that Jerusalem is supposed to be an international city, not a part of either the proposed Jewish or Arab state. Following the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, West Jerusalem was controlled by Israel, while East Jerusalem (including the Old City), and the West Bank were controlled by Jordan. Jordan's authority over the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) was not recognized internationally, except by the United Kingdom and Pakistan.

Following the 1967 Six-Day War, Israel gained control also of East Jerusalem, and began taking steps to unify the city under Israeli control.

In 1988, Jordan withdrew all its claims to the West Bank (including Jerusalem), yielding them to the Palestine Liberation Organization.

The status of Palestinians in East Jerusalem is also controversial. The Palestinian residents of East Jerusalem have a ‚Äúpermanent resident‚ÄĚ status, which allows them to move within Israel proper. However should they move out of Israel proper (for example, into the Palestinian territories), this status will be revoked and they will not be able to return. Since many have extended families in the West Bank, only miles away, this often implies great difficulty. The matter of Israeli citizenship and related laws is a complex matter for the Palestinians.

Family members not residing in East Jerusalem prior to the point of Israeli control must apply for entry into East Jerusalem for family reunification with the Ministry of the Interior. Palestinians complain that such applications have been arbitrarily denied for purposes of limiting the Palestinian population in East Jerusalem, while Israeli authorities claim they treat Palestinians fairly. These and other aspects have been a source of criticism from Palestinians and Israeli human rights organizations, such as B'Tselem.

Status as Israel's capital

In 1980 the Israeli Knesset passed the Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel confirming Jerusalem's status as the nation's "eternal and indivisible capital."

Costa Rica and El Salvador have their embassies in Jerusalem (since 1984), but the Consulate General of Greece as well as that of the United Kingdom and the United States are based there. Additionally, Bolivia and Paraguay have their embassies in Mevasseret Zion, a suburb of Jerusalem.

All the branches of Israeli government (presidential, legislative, judicial, and administrative) are seated in Jerusalem. The Knesset building is well known in Jerusalem, but still very few countries maintain their embassies in Jerusalem.

Palestinian groups claim either all of Jerusalem (Al-Quds) or East Jerusalem as the capital of a future Palestinian state.

United Nations position

The United Nations’ position on the question of Jerusalem is contained in General Assembly resolution 181(11) and subsequent resolutions of the General Assembly and the Security Council.

The UN Security Council, in UN Resolution 478, declared that the 1980 Jerusalem Law declaring Jerusalem as Israel's "eternal and indivisible" capital was "null and void and must be rescinded forthwith" (14-0-1, with the United States abstaining). The resolution instructed member states to withdraw their diplomatic representation from the city.

Before this resolution, 13 countries maintained embassies in Jerusalem. Following the UN resolution, all 13 moved their embassies to Tel Aviv. Two moved theirs back to Jerusalem in 1984.

United States position

The United States Jerusalem Embassy Act, passed by Congress in 1995, states that "Jerusalem should be recognized as the capital of the State of Israel; and the United States Embassy in Israel should be established in Jerusalem no later than May 31, 1999." As a result of the Embassy Act, official U.S. documents and websites refer to Jerusalem as the capital of Israel.

However, for years the relocation of the embassy from Tel Aviv was suspended semi-annually by the United States president, stating each time that "[the] Administration remains committed to beginning the process of moving our embassy to Jerusalem.‚ÄĚ

On December 6, 2017 U.S. President Donald Trump officially recognized Jerusalem as Israel's capital and announced his intention to move the American embassy to Jerusalem. On May 14, 2018, the United States officially moved the location of its embassy to Jerusalem, transforming its Tel Aviv location into a consulate.

Jerusalem and Judaism

Jerusalem has long been embedded into the religious consciousness of the Jewish people. Jews have always identified with the struggle of King David to capture Jerusalem and his desire to build the Jewish temple there as described in the Book of Samuel.

Jerusalem and prayer

The daily prayers recited by religious Jews three times a day over the last two thousand years mention Jerusalem and its functions multiple times. Some examples from the siddur (prayer book) and the amidah are:

(Addressing God): "And to Jerusalem, your city, may you return in compassion, and may you rest within it, as you have spoke. May you rebuild it soon in our days as an eternal structure, and may you speedily establish the throne of (King) David within it. Blessed are you God, the builder of Jerusalem...May our eyes behold Your return to Zion in compassion. Blessed are you God, who restores his presence to Zion."

Additionally when partaking of a daily meal with bread, the following is part of the "Grace after Meals" which must be recited:

Have mercy, Lord our God, on Israel your people, on Jerusalem your city, on Zion, the resting place of your glory, on the monarchy of (King David) your anointed, and on the great and holy (Temple) house upon which your name is called…. Rebuild Jerusalem, the holy city, soon in our days. Blessed are you God who rebuilds Jerusalem in his mercy. Amen.

When partaking of a light meal, the thanksgiving blessing states:

Have mercy, Lord, our God, on Israel, your people; on Jerusalem, your city; and on Zion, the resting place of your glory; upon your altar, and upon your temple. Rebuild Jerusalem, the city of holiness, speedily in our days. Bring us up into it and gladden us in its rebuilding and let us eat from its fruit and be satisfied with its goodness and bless you upon it in holiness and purity. For you, God, are good and do good to all and we thank you for the land and for the nourishment…

When the Jews were exiled, first by the Babylonian Empire about 2,500 years ago and then by the Roman Empire 2,000 years ago, the great rabbis and scholars of the mishnah and Talmud instituted the policy that each synagogue should replicate the original Jewish temple and that it be constructed in such a way that all prayers in the siddur be recited while facing Jerusalem, as that is where the ancient temple stood and it was the only permissible place of the sacrificial offerings.

Thus, synagogues in Europe face south; synagogues in North America face east, synagogues in countries to the south of Israel, such as Yemen and South Africa, face north; and synagogues in those countries to the east of Israel, face west. Even when in private prayer and not in a synagogue, a Jew faces Jerusalem, as mandated by Jewish law compiled by the rabbis in the Shulkhan Arukh.

Western Wall in Jerusalem

The Western Wall, in the heart of the Old City of Jerusalem, is generally considered to be the only remains of the Second Temple from the era of the Roman conquests. There are said to be esoteric texts in Midrash that mention God's promise to keep this one remnant of the outer temple wall standing as a memorial and reminder of the past, hence, the significance of the "Western Wall" (kotel hama'aravi).

Jerusalem and the Jewish religious calendar

The yearning of Jews for Jerusalem can be seen in the words by which two major Jewish festivals conclude, namely the phrase "Next Year in Jerusalem" (l'shanah haba'ah birushalayim).

- At the end of the Passover Seder prayers about the miracles surrounding the Exodus from ancient Egypt conclude with the loud repetitious singing of "Next Year in Jerusalem."

- The holiest day on the Jewish calendar, Yom Kippur, also concludes with the singing and exclamation of "Next Year in Jerusalem."

Each of these days has a sacred test associated with it, the Hagada for Pesach (Passover) and the Machzor for Yom Kippur (Day of Atonement), which stresses the longing to return to Jerusalem.

The saddest day of fasting on the Jewish religious calendar is the Ninth of Av, when Jews traditionally spend the day crying for having lost two of their most holy temples and for the destruction of Jerusalem. This major 24-hour fast is preceded on the calendar by two minor dawn to dusk fasts. These are the Tenth of Tevet, mourning the time Babylonia laid siege to the First Temple, and the Seventeenth of Tammuz, that mourns the time Rome broke through the outer walls of the Second Temple.

Many large state gatherings of the State of Israel take place at the old site of the Second Temple, including the official swearing-in of different Israel army officers units, national ceremonies such as memorial services for fallen Israeli soldiers on Yom Hazikaron, huge celebrations on Israel Independence Day (Yom Ha'atzmaut), huge gatherings of tens of thousands on Jewish religious holidays, and on-going daily prayers by regular attendees.

Jerusalem in Christianity

For Christians, Jerusalem gains its importance from its place in the life of Jesus, in addition to its place in the Old Testament, the Hebrew Bible, which is part of Christian sacred scripture.

Jerusalem is the place where Jesus was brought as a child to be ‚Äúpresented‚ÄĚ at the Temple (Luke 2:22) and to attend festivals (Luke 2:41). According to the Gospels, Jesus preached and healed in Jerusalem, especially in the Temple courts. There is also an account of Jesus chasing traders from the sacred precincts (Mark 11:15). At the end of each of the Gospels, there are accounts of Jesus' Last Supper in an ‚Äúupper room‚ÄĚ in Jerusalem, his arrest in Gethsemane, his trial, his crucifixion at Golgotha, his burial nearby, and his resurrection and ascension.

The place of Jesus' anguished prayer and betrayal, Gethsemane, is probably somewhere near the Mount of Olives. Jesus' trial before Pontius Pilate may have taken place at the Antonia fortress, to the north of the Temple area. Popularly, the exterior pavement where the trial was conducted is beneath the Convent of the Sisters of Zion. Other Christians believe that Pilate tried Jesus at Herod's Palace on Mount Zion.

The Via Dolorosa, or way of suffering, is regarded by many as the traditional route to Golgotha, the place of crucifixion, and now functions as an important pilgrimage destination. The route ends at the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. The Holy Sepulchre is traditionally believed to be the location of Golgotha and Jesus' nearby tomb. The original church was built there in 336 by Constantine I. The Garden Tomb is a popular pilgrimage site near the Damascus Gate.

Tradition holds that the place of the Last Supper is the Cenacle, a site the history of which is debated by Jews, Christians, and Muslims, who all make historical claims of ownership.

Jerusalem in Islam

Muslims traditionally regard Jerusalem as having a special religious status. This reflects the fact that David, Solomon, and Jesus are considered by Muslims as Prophets of Islam. Furthermore, the first qibla (direction of prayer) in Islam, even before the kabah in Mecca is Jerusalem. The "farthest Mosque" (al-masjid al-Aqsa) in verse 17:1of the Qur'an is traditionally interpreted by Muslims as referring to the Temple Mount in Jerusalem.

For Muslims, Muhammad is believed to have been taken by the flying steed Buraq in a single night to visit Jerusalem on the night of the Isra and Mi'raj (Rajab 27).

Several hadiths refer to Jerusalem (Bayt al-Maqdis) as the place where all mankind will be gathered on the Day of Judgment.

The earliest dated stone inscriptions containing verses from the Qur'an appear to be Abd al-Malik's* in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, from 693 C.E.

After the conquest of Jerusalem by the armies of the second Caliph, Umar ibn al-Khattab, parts of the city soon took on a Muslim character. According to Muslim historians, the city insisted on surrendering to the Caliph directly rather than to any general, and he signed a pact with its Christian inhabitants, the Covenant of Umar. He was horrified to find the Temple Mount (Haram al Sharif) being used as a rubbish dump, and ordered that it be cleaned up and prayed there. However, when the bishop invited him to pray in the Church of the Holy Sepulchre, he refused, lest he create a precedent for its use as a mosque. According to some Muslim historians, he also built a crude mosque on the Temple Mount, which would be replaced by Abd al-Malik. The Byzantine chronicler Theophanes Confessor (751‚Äď818) gives a slightly different picture of this event, claiming that Umar "began to restore the Temple at Jerusalem" with encouragement from local Jews.

In 688, the Caliph Abd al-Malik built the Dome of the Rock on the Temple Mount, also known as Noble Sanctuary; in 728, the cupola over the Al-Aqsa Mosque was erected, the same being restored in 758‚Äď775 by Al-Mahdi. In 831, Al-Ma'mun restored the Dome of the Rock and built the octagonal wall. In 1016, the Dome was partly destroyed by earthquakes, but it was repaired in 1022.

Arguments for and against internationalization

The proposal that Jerusalem should be a city under international administration is still considered the best possible solution by many with an interest in a future of peace and prosperity for the region.

Other negotiations regarding the future status of Jerusalem are based on the concept of partition. One scheme, for example, would give Israel the Jewish quarter and the Western Wall, but the rest of the Old City and the Temple Mount would be transferred to a new Palestinian state. Many Israelis however, are opposed to any division of Jerusalem. This is based on cultural, historic, and religious grounds. Since so many parts of the Old City are sacred to Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, many argue that the city should be under international or multilateral control.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abdul Hadi, Mahdi. 1995/96. "The Future of Jerusalem-A Palestinian Perspective." Shu'un Tanmawiyyeh 5, nos. 2 -3: 11-16.

- Abdul Hadi, Mahdi. 1996. "The Ownership of Jerusalem: A Palestinian View." In Jerusalem Today: What future for the Peace Process? Reading: Garnet Publishing.

- Abdul Hadi, Mahdi Meron Benvenisti, Naomi Chazan, and Ibrahim Dakkak, 1995. "In Search of Solutions: A Roundtable Discussion." Palestine-Israel Journal 2, no. 2: 87-96.

- Abu Odeh, Adnan. 1992. "Two Capitals in an Undivided Jerusalem." Foreign Affairs 70: 183-88.

- Abu Arafah, Adel Rahman. 1995/96. "Projection of the Future Status of Jerusalem." Shu'un Tanmawiyyeh 5, nos. 2-3: 2-10.

- Albin, Cecilia, Moshe Amirav, and Hanna Siniora. 1991/92. Jerusalem: An Undivided City as Dual Capital. Israeli-Palestinian Peace Research Project, Working Paper Series No. 16.

- Amirav, Moshe. "Blueprint for Jerusalem." The Jerusalem Report, 12 March 1992, p. 41.

- Baskin, Gershon. 1994. Jerusalem of Peace. Jerusalem: Israel/Palestine Center for Research and Information.

- Baskin, Gershon and Robin Twite, eds. 1993. The Future of Jerusalem. Proceedings of the First Israeli-Palestinian International Academic Seminar on the Future of Jerusalem, Jerusalem, March 1993. Jerusalem: Israel/Palestine Center for Research and Information.

- Baskin, Gershon, ed. June 1994. "New Thinking on the Future of Jerusalem. A Model for the Future of Jerusalem: Scattered Sovereignty. The IPCRI Plan." Israel/Palestine Issues in Conflict, Issues for Cooperation 3, no. 2.

- Beckerman, Chaia, ed. 1996. Negotiating the Future: Vision and Realpolitik in the Quest for a Jerusalem of Peace. Jerusalem: Israel/Palestine Center for Research and Information.

- Beilin, Yossi. 1999. Touching Peace: From the Oslo Accord to a Final Agreement. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0297643169

- Benvenisti, Meron. 1996. "Unraveling the Enigma." Chapter 7 of City of Stone: The Hidden History of Jerusalem. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 0520205219

- Bring, Ove. 1996. "The Condominium Solution as a Gradual Process: Thoughts of an International Lawyer After the Conference." Afterword to Negotiating the Future: Vision and Realpolitik in the Quest for a Jerusalem of Peace. Ed. Chaia Beckerman. Jerusalem: Israel/Palestine Center for Research and Information.

- Bundy, Rodman. 1997. "Jerusalem in International Law." In Ghada Karmi (ed.) Jerusalem Today: What future for the Peace Process? Ithaca Press. ISBN 0863722261

- Chazan, Naomi. 1991. "Negotiating the Non-Negotiable: Jerusalem in the Framework of an Israeli-Palestinian Settlement." Occasional Paper, no. 7. Cambridge, MA: American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

- Cheshin, Amir S., Bill Hutman and Avi Melamed. 1999. "A Path to Peace Not Taken." Chapter 12 of Separate and Unequal: The Inside Story of Israeli Rule in East Jerusalem. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674801369

- Emmett, Chad F. 1997. "The Status Quo Solution For Jerusalem." Journal of Palestine Studies 26, no. 2: 16-28.

- Friedland, Roger, and Richard Hecht. 1996. "Heart of Stone." Chapter 18 of To Rule Jerusalem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521440467

- Gold, Dore. 1995. "Jerusalem: Final Status Issues." Israel-Palestinian Study No. 7. Tel Aviv: Jaffee Centre.

- Heller, Mark A. and Sari Nusseibeh. 1991. No Trumpets, No Drums: A Two-State Settlement of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict. New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN 0809073935

- Hirsch, Moshe, Deborah Housen-Couriel, and Ruth Lapidoth. 1995. Whither Jerusalem? Proposals and Positions Concerning the Future of Jerusalem. Springer. ISBN 9041100776

- Klein, Menachem. 1999. "Doves in the Skies of Jerusalem". Jerusalem: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies. [Hebrew]

- Kollek, Teddy. 1977. "Jerusalem." Foreign Affairs 55, no. 4: 701-16.

- Kollek, Teddy. 1998/89. "Sharing United Jerusalem." Foreign Affairs (Winter): 156-68.

- Kollek, Teddy. 1990. "Whose Jerusalem?" New Outlook (Jan./Feb): 18 and 20.

- Latendresse, Anne. 1995-96. "Between Myth and Reality: Israeli Perspectives on Jerusalem." Shu'un Tanmawiyyeh 5, nos. 2-3: 2-10.

- Lustick, Ian S. 1993/94. "Reinventing Jerusalem." Foreign Policy 93: 41-59.

- Mansour, Camille. 1977. "Jerusalem: International Law and Proposed Solutions." Jerusalem: What makes for Peace! A Palestinian Christian Contribution to Peacemaking. Ed. Naim Ateek, Dedar Duaybis, and Marla Schrader. Jerusalem: Sabeel Liberation Theology Center.

- Nusseibeh, Sari, Ruth Lapidoth, Albert Aghazarian, Moshe Amirav and Hanna Seniora. 1993. "Sovereignty; City Government: Creative Solutions." Section 3 of Jerusalem: Visions of Reconciliation. An Israeli-Palestinian Dialogue. Proceedings of the United Nations Department of Public Information's Encounter for Greek Journalists on the Question of Palestine, 27-28 April 1993, Athens, Greece.

- Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs (PASSIA). 1996. Documents on Jerusalem. Jerusalem: PASSIA.

- Quigley, John. 1996. "Jerusalem in International Law." In Jerusalem Today: What future for the Peace Process? Reading: Garnet Publishing.

- Segal, Jerome M. 1997. "Is Jerusalem Negotiable?" Israel/Palestine Center for Research and Information, Final Status Publications Series Number 1, July 1997. Jerusalem: IPCRI.

- Shtayyeh, Mohammad, ed. 1998. "Scenarios on the Future of Jerusalem." Jerusalem: Palestinian Center for Regional Studies.

- Shuqair, Riziq. 1996. "Jerusalem: Its Legal Status and the Possibility of a Durable Settlement. Ramallah": Al-Haq.

- Tufakji, Khalil. 1995. "Proposal for Jerusalem." Palestine Report, 20 October, pp. 8-9.

- Whitbeck, John V. 1998. "The Jerusalem Question: Condominium as Compromise." The Jerusalem Times, 24 July, p. 5.

- Whitbeck, John V. 1998. "The Road to Peace Starts in Jerusalem: The Condominium Solution." Middle East Policy 3, no. 3 (1994). Reprinted in Mohammad Shtayyeh, ed. Scenarios on the Future of Jerusalem (Jerusalem: Palestinian Center for Regional Studies), pp. 169-184. (Page references are to reprint edition).

External links

All links retrieved December 23, 2024.

- What makes Jerusalem so holy? BBC

- The Knesset

- The Jerusalem Post

- Jerusalem Tourist Israel

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.