Orthodox Judaism

| Category |

| Jews · Judaism · Denominations |

|---|

| Orthodox · Conservative · Reform |

| Haredi · Hasidic · Modern Orthodox |

| Reconstructionist · Renewal · Rabbinic · Karaite |

| Jewish philosophy |

| Principles of faith · Minyan · Kabbalah |

| Noahide laws · God · Eschatology · Messiah |

| Chosenness · Holocaust · Halakha · Kashrut |

| Modesty · Tzedakah · Ethics · Mussar |

| Religious texts |

| Torah · Tanakh · Talmud · Midrash · Tosefta |

| Rabbinic works · Kuzari · Mishneh Torah |

| Tur · Shulchan Aruch · Mishnah Berurah |

| Šł§umash ¬∑ Siddur ¬∑ Piyutim ¬∑ Zohar ¬∑ Tanya |

| Holy cities |

| Jerusalem · Safed · Hebron · Tiberias |

| Important figures |

| Abraham · Isaac · Jacob/Israel |

| Sarah · Rebecca · Rachel · Leah |

| Moses · Deborah · Ruth · David · Solomon |

| Elijah · Hillel · Shammai · Judah the Prince |

| Saadia Gaon · Rashi · Rif · Ibn Ezra · Tosafists |

| Rambam · Ramban · Gersonides |

| Yosef Albo · Yosef Karo · Rabbeinu Asher |

| Baal Shem Tov · Alter Rebbe · Vilna Gaon |

| Ovadia Yosef · Moshe Feinstein · Elazar Shach |

| Lubavitcher Rebbe |

| Jewish life cycle |

| Brit · B'nai mitzvah · Shidduch · Marriage |

| Niddah · Naming · Pidyon HaBen · Bereavement |

| Religious roles |

| Rabbi · Rebbe · Hazzan |

| Kohen/Priest · Mashgiach · Gabbai · Maggid |

| Mohel · Beth din · Rosh yeshiva |

| Religious buildings |

| Synagogue · Mikvah · Holy Temple / Tabernacle |

| Religious articles |

| Tallit · Tefillin · Kipa · Sefer Torah |

| Tzitzit · Mezuzah · Menorah · Shofar |

| 4 Species · Kittel · Gartel · Yad |

| Jewish prayers |

| Jewish services · Shema · Amidah · Aleinu |

| Kol Nidre · Kaddish · Hallel · Ma Tovu · Havdalah |

| Judaism & other religions |

| Christianity · Islam · Catholicism · Christian-Jewish reconciliation |

| Abrahamic religions · Judeo-Paganism · Pluralism |

| Mormonism · "Judeo-Christian" · Alternative Judaism |

| Related topics |

| Criticism of Judaism · Anti-Judaism |

| Antisemitism · Philo-Semitism · Yeshiva |

Orthodox Judaism is the Jewish tradition that adheres to a relatively strict interpretation and application of the laws and ethics promulgated in the Talmud and later rabbinical tradition. It is distinguished from other contemporary types of Judaism, such as Reform, Conservative, and secular Judaism, in its insistence that traditional Jewish law remains binding on all modern Jews. Orthodox Judaism strictly practices such Jewish traditions as the kosher dietary laws, daily prayers and ablutions, laws regarding sexual purity, intensive Torah study, and gender segregation in the synagogue.

Subgroups within Orthodox Judaism include Modern Orthodoxy and Haredi Judaism, which includes Hasidism. The Modern and Haredi variants differ in their attitudes toward secular study, dress, and interaction with the wider Gentile world. The Hasidic movement, which is a subset of Haredi Judaism, is less focused on the strict study of the Talmud and is more open to mystical kabbalistic ideas.

Orthodox Judaism has grown rapidly in recent decades as many Jews have rejected secularism and sought to return to their religious roots.

The name "Orthodox"

The word "orthodox" itself is derived from the Greek orthos meaning "straight/correct" and doxa meaning "opinion." While many Orthodox Jews accept the term, others reject it as a modern innovation derived from Christian categories. Many Orthodox Jews prefer to call their faith Torah Judaism.

Use of the Orthodox label began toward the beginning of the nineteenth century. Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch wrote, in 1854, that "it was not 'Orthodox' Jews who introduced the word 'orthodox' into Jewish discussion. It was the modern 'progressive' Jews who first applied the name to 'old,' 'backward' Jews as a derogatory term. This name was… resented by 'old' Jews. And rightfully so."

Others, however, say that the American Rabbi Isaac Leeser was the first to use the term, in his journal The Occident. This usage was clearly not derogatory, as Leeser was an observant Jew himself, and his journal's target audience was the more traditional, or "Orthodox" Jew.

Basic doctines

Some of the basic beliefs and attitudes of Orthodox Judaism include:

- Belief that the Torah (that is, the Pentateuch) and its laws were transmitted by God to Moses, are eternal, and are unalterable

- Belief that there is also an Oral Law, the authoritative interpretation of the written Torah, which was also transmitted by God to Moses and is now embodied in the Talmud, Midrash, and related texts

- Belief that God has made an exclusive, unbreakable covenant with the Children of Israel to be governed by the Torah, which is binding on all Jews

- Belief in a Jewish eschatology, including a Messiah, a rebuilt Temple in Jerusalem, and a resurrection of the dead

- Adherence to Halakha, or the tradition of Jewish law, usually as codified in the sixteenth century Shulkhan Arukh

- Acceptance of traditional halakhic codes as authoritative and that new halakhic rulings must not contradict accepted precedent

- Belief in the 13 Jewish principles of faith as stated by the rabbinical sage Maimonides

- Acceptance of Orthodox rabbis as authoritative interpreters and judges of Jewish law.

Diversity within Orthodox Judaism

While Orthodox Jews are united in believing that both the Written Law and the Oral Torah must not be rejected or modified, there is no one unifying Orthodox body, and, thus, there is no one official statement of Orthodox principles of faith. Moreover, the Talmud itself provides for divergent traditions on many issues.

Given this relative philosophic flexibility, variant attitudes are possible, particularly in areas not explicitly demarcated by the Halakha. These areas are referred to as devarim she'ein lahem shiur ("things with no set measure"). The result is a relatively broad range of worldviews within the Orthodox tradition.

Subgroups

The above differences are realized in the various subgroups of Orthodoxy, which maintain significant social differences, and differences in understanding Halakha. These groups, broadly, comprise Modern Orthodox Judaism and Haredi Judaism, the latter including both Hasidic and non-Hasidic sects.

- Modern Orthodoxy advocates increased integration with non-Jewish society, regards secular knowledge as inherently valuable, and is somewhat more willing revisit questions of Jewish law in Halakhic context

- Haredi Judaism advocates a greater degree of segregation from non-Jewish culture. It is also characterized by its focus on community-wide Torah study. Academic interest is normally directed toward the religious studies found in the yeshiva, rather than secular academic pursuits

- Hasidic Judaism likewise generally prefers separation from non-Jewish society, but places greater emphasis than most other Orthodox groups on the Jewish mystical tradition known as Kabbalah

- A fourth movement within Orthodoxy, Religious Zionism, is characterized by belief in the importance of the modern state of Israel to Judaism, and often intersects with Modern Orthodoxy.

More specifically, the greatest differences among these groups deal with such issues as:

- The degree to which an Orthodox Jew should integrate and/or disengage from secular society

- The extent of acceptance of traditional authorities as non secular, scientific, and political matters, vis-a-vis accepting secular and scientific views on some matters

- The weight assigned to Torah study versus secular studies or other pursuits

- The centrality of yeshivas as the place for personal Torah study

- The importance of a central spiritual guide in areas outside of Halakhic decision

- the importance of maintaining non-Halakhic Jewish customs in such areas as dress, language, and music

- The relationship of the modern state of Israel to Judaism

- The role of women in (religious) society

- The nature of the relationship of Jews to non-Jews

- The importance or legitimacy of the Kabbalah (Jewish mystical tradition) as opposed to traditional Talmudic study

For guidance in practical application of Jewish law (Halakha) the majority of Orthodox Jews ultimately appeal to the Shulchan Aruch, the Halakic code composed in the sixteenth century by Rabbi Joseph Caro together with its associated commentaries. Thus, at a general level, there is a large degree of conformity among Orthodox Jews.

Besides the broadly defined subgroups mentioned above, other differences result from the historic dispersal of the Jews and the consequent regional differences in practice.

- Ashkenazic Orthodox Jews have traditionally base most of their practices on the Rema, the gloss on the Shulchan Aruch by Rabbi Moses Isserles, reflecting differences between Ashkenazi and Sephardi custom. More recently the Mishnah Berurah has become authoritative, and Ashkenazi Jews often choose to follow the opinion of the Mishna Brurah instead of a particular detail of Jewish law as presented in the Shulchan Aruch.

- Mizrahi and Sephardic Orthodox Jews generally base their practice on the Shulchan Aruch. However, two recent works of Halakha, Kaf HaChaim and Ben Ish Chai, have become authoritative in Sephardic communities.

- Traditional Yemenite Jews base most of their practices on the Mishneh Torah, Maimonides' earlier compendium of Halakha, written several centuries before the Shulchan Aruch. The sect known as the Talmidei haRambam also keep Jewish law as codified in the Mishneh Torah.

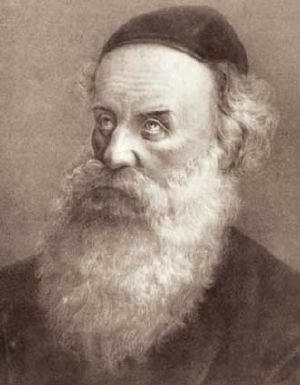

- Chabad Lubavitch Hasidim generally follow the rulings of Shneur Zalman of Liadi, the founder the Chabad branch of Hasidic Judaism, in his Halakhic work known as the Shulchan Aruch HaRav.

- A small number‚ÄĒsuch as the Romaniote Jews‚ÄĒtraditionally follow the Jerusalem Talmud over the Babylonian Talmud

It should be noted that on an individual level there is a considerable range in the level of observance among Orthodox Jews. Thus, there are those who would consider themselves "Orthodox" and yet may not be observant of, for example, the laws of family purity.

Theology

Orthodoxy collectively considers itself the only true heir to the Jewish tradition. Non-Orthodox Jewish movements are, thus, generally considered to be unacceptable deviations from authentic Judaism.

Like all forms of religious Judaism, Orthodox Judaism begins with an affirmation of monotheism‚ÄĒthe belief in one God. Among the in-depth explanations of that belief are Maimonidean rationalism, Kabbalistic mysticism, and even Hasidic pantheism.

Orthodox Judaism maintains the historical understanding of Jewish identity. A Jew is someone who was born to a Jewish mother, or who converts to Judaism in accordance with Jewish law and tradition. Orthodoxy thus rejects patrilineal descent as a means of establishing Jewish national identity. Similarly, Orthodoxy strongly condemns intermarriage unless the non-Jew has converted. Intermarriage is seen as a deliberate rejection of Judaism, and an intermarried person is effectively cut off from most of the Orthodox community. However, some Chabad Lubavitch and Modern Orthodox Jews do reach out to intermarried Jews. Orthodox Judaism naturally rejects such innovations as homosexual marriage and the ordination of female rabbis.

Orthodox Judaism holds to traditions such as the Jewish dietary laws, sexual purity laws, daily prayers and hand-washing, and other rituals rejected by Reform Jews as outmoded and no longer binding. Because it hopes for the restoration of the Temple of Jerusalem, it also generally foresees the restoration of the Jewish priesthood and ceremonial offerings.

Given Orthodoxy's view of Jewish law's divine origin, no underlying principle may be compromised in accounting for changing political, social, or economic conditions. Jewish law today is based on the commandments in the Torah, as viewed through the discussions and debates contained in classical rabbinic literature, especially the Mishnah and the Talmud. Orthodox Judaism thus holds that the Halakha represents the will of God, either directly, or as closely to directly as possible. In this view, the great rabbis of the past are closer to the divine revelation than modern ones. By corollary, one must be extremely conservative in changing or adapting Jewish law. The study of the Talmud is considered to be the greatest mitzvah of all.

Haredi Judaism views higher criticism of the Talmud, let alone the Bible itself, as inappropriate, or even heretical. Many within Modern Orthodox Judaism, however, do not have a problem with historical scholarship in this area. Modern Orthodoxy is also somewhat more willing to consider revisiting questions of Jewish law through Talmudic arguments. Notable examples include acceptance of rules permitting farming during the Shmita year‚ÄĒthe seventh year of the seven-year agricultural cycle mandated by the Torah for the Land of Israel‚ÄĒand permitting the advanced religious education of women.

The development of today's Orthodoxy

Orthodox Jews maintain that contemporary Orthodox Judaism holds the same basic philosophy and legal framework that existed throughout Jewish history‚ÄĒwhereas the other denominations depart from it. Orthodox Judaism, as it exists today, sees itself as the direct outgrowth of the revelation at Mount Sinai, that stretches, through the oral law, from the time of Moses to the time of the Mishnah and Talmud, ongoing until the present time. However, understood as a major denomination within modern religion of Judaism generally, Orthodox Judaism evolved in reaction to certain modernizing tendencies within the general Jewish population, especially in Europe and the United States.

In the early 1800s, elements within German Jewry sought to reform Jewish belief and practice in response to The Age of Enlightenment and the Jewish Emancipation. In light of modern scholarship, they denied divine authorship of the Torah, declared only the moral aspects of biblical laws to be binding, and stated that the rest of Halakha need no longer be viewed as normative (see Reform Judaism).

At the same time, many German Jews strictly maintained their adherence to Jewish law while simultaneously engaging with a post-Enlightenment society. This camp was best represented by the work and thought of Rabbi Samson Raphael Hirsch. Hirsch held that Judaism demands an application of Torah thought to the entire realm of human experience‚ÄĒincluding the secular disciplines. While insisting on strict adherence to Jewish beliefs and practices, he held that Jews should attempt to engage and influence the modern world and encouraged those secular studies compatible with Torah thought. His approach became known as Neo-Orthodoxy, and later as Modern Orthodoxy. Other, more traditional, forms of Orthodox Judaism developed in eastern Europe and the Middle East with relatively little influence from secularizing influences.

In 1915, Yeshiva College (later Yeshiva University) and its Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary were established in New York City for rabbinical training in a Modern Orthodox milieu. Eventually a school branch was established in Los Angeles, California. A number of other smaller but influential Orthodox seminaries, mostly Haredi, were also established throughout the country, most notably in New York City, Baltimore, and Chicago. The Haredi yeshiva in Lakewood, New Jersey is the largest institution of its kind. It is estimated that presently there are more Jews studying in yeshivot (Talmud schools) and kollelim (post-graduate Talmudical colleges for married students) than at any other time in history.

In the United States, there are several Orthodox denominations, such as, Agudath Israel (Haredi), the Orthodox Union (Modern), and the National Council of Young Israel (Modern), none of which represents a majority of U.S. Orthodox congregations.

While Modern Orthodoxy is considered traditional by most Jews today, some within the Orthodox community question its validity due to its relatively liberal attitude on Halakhic issues such as interaction with Gentiles, modern dress, secular study, and critical study of the Hebrew Bible and Talmud. In the late twentieth century, a growing segment of the Orthodox population has taken the stricter approach.

The Chief Rabbinate of Israel was founded with the intention of representing all of Judaism within the State of Israel, and has two chief rabbis: one Ashkenazic and one Sephardic. The rabbinate, however, is not accepted by most Israeli Haredi groups.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Danzger, Murray Herbert. Returning to Tradition: The Contemporary Revival of Orthodox Judaism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1989. ISBN 9780300039474.

- Davidman, Lynn. Tradition in a Rootless World: Women Turn to Orthodox Judaism. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991. ISBN 9780520075450.

- Freundel, Barry. Contemporary Orthodox Judaism's Response to Modernity. Jersey City, N.J.: KTAV Pub. House, 2004. ISBN 9780881257786.

- Hirsch, Ammiel, and Yaakov Yosef Reinman. One People, Two Worlds: An Orthodox Rabbi and a Reform Rabbi Explore the Issues That Divide Them. New York: Schocken Books, 2002. ISBN 9780805211405.

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.