Talmud

The Talmud (Hebrew: ◊™◊ú◊ě◊ē◊ď) is a record of rabbinical discussions pertaining to Jewish law, biblical interpretation, ethics, customs, and history. It is the basis for all codes of rabbinical law and is much quoted in other Jewish literature.

The Talmud has two basic components: the Mishnah (c. 200 C.E.), the first written compendium of Judaism's Oral Law; and the Gemara (c. 500 C.E.), a rabbinical discussion of the Mishnah and related writings that often ventures into other subjects and expounds broadly on the Hebrew Bible. Printed editions of the Talmud also contain later commentaries from rabbinical authorities through the Middle Ages. The terms Talmud and Gemara are often used interchangeably.

There are two versions of the Talmud‚ÄĒthe Babylonian Talmud and the Jerusalem Talmud‚ÄĒeach containing basically the same Mishnah but a different Gemara. Of these, the Babylonian Talmud is larger, better edited, and more influential. Other commentaries were also added to later editions of the Talmud.

In European history, the Talmud was sometimes suppressed by the Catholic Church, and it became a source of anti-semitic literature in modern times, when excerpts from it were quoted to "prove" ideas of Jewish arrogance and hatred toward Gentiles. In fact, the Talmud contains the opinions of hundreds of rabbis, often including strong disagreements on many subjects. Like the Bible itself, it can be used to support varying positions on many subjects.

History

Oral Law

Rabbinical tradition holds that the Talmud expresses a sacred Oral Torah, equally authoritative to the Written Law given to Moses at Sinai. Originally, Jewish legal and biblical scholarship was also oral. This situation changed drastically, however, mainly as the result of the defeat of the Jewish Revolt against Rome in the year 70 C.E. and the consequent upheaval of Jewish social and legal norms. As the rabbis were required to face a new reality‚ÄĒespecially the fact of Judaism without a Temple‚ÄĒthere was a flurry of legal discourse and the tradition of oral scholarship was committed to writing.

The earliest recorded Oral Law may have been of the midrashic form, in which Jewish legal discussion was structured as exegetical commentary on the Pentateuch. An alternative form, organized by subject matter instead of by biblical verse, became dominant about the year 200 C.E., when Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi redacted the Mishnah.

Mishnah

The Mishnah forms the core of the Talmud. It is a compilation of legal opinions and debates of leading rabbis of the second century. The rabbis of the Mishnah are known as tannaim, meaning roughly "sages." Since it sequences its laws by subject matter instead of by biblical context, the Mishnah discusses individual subjects more thoroughly than the Midrash, and it includes a much broader selection of halakhic (legal) subjects than the Midrash. The Mishnah's topical organization thus became the framework of the Talmud as a whole.

In addition to the Mishnah, other rabbinical works were recorded at about the same time or shortly thereafter. The Talmud frequently refers to these tannaic statements in order to compare them to those contained in the Mishnah and to support or refute the propositions of various rabbinical authorities. All such non-Mishnaic sources of the tannaim are termed baraitot (lit. outside material, "Works external to the Mishnah"; sing. baraita ◊Ď◊®◊ô◊ô◊™◊ź).

Gemara

In the three centuries following the redaction of the Mishnah, rabbis throughout Palestine and Babylonia analyzed, debated and discussed that work. These discussions form the Gemara (◊í◊ě◊®◊ź). The rabbis of the Gemara are known as amoraim (sing. amora ◊ź◊ě◊ē◊®◊ź). Gemara means ‚Äúcompletion,‚ÄĚ from gamar ◊í◊ě◊®¬†: Hebrew to complete; Aramaic to study.

Much of the Gemara consists of legal analysis. The starting point for the analysis is usually a legal statement found in a Mishnah. The statement is then analyzed and compared with other statements in a dialectical exchange between two (frequently anonymous and sometimes metaphorical) disputants, termed the makshan (questioner) and tartzan (answerer).

These exchanges form the "building-blocks" of the Gemara; the name for a passage of Gemara is a sugya (◊°◊ē◊í◊ô◊ź; plural sugyot). A Sugya will typically be comprised of a detailed proof-based elaboration of a mishnaic statement.

In a given sugya, scriptural, tannaic and amoraic statements are brought to support the various opinions. In so doing, the Gemara will often include disagreements between tannaim and amoraim, and compare the mishnaic views with passages from the Beraita. Rarely are debates formally closed; in many instances, the final word determines the practical law, although there are many exceptions to this principle.

Halakha and Aggadah

The Talmud contains a vast amount of material and touches on a great many subjects. Traditionally talmudic statements can be classified into two broad categories: halakhic and agaddic. Halakhic statements are those which directly relate to questions of Jewish law and practice (Halakha). Aggadic statements are those which are not legally related, but rather are exegetical, homiletical, ethical, or historical in nature (Aggadah).

Babylon and Jerusalem

The process of Gemara proceeded in the two major centers of Jewish scholarship, Palestine and Babylonia. Correspondingly, two bodies of analysis developed, and two works of the Talmud were created. The older compilation is called the Jerusalem Talmud or the Talmud Yerushalmi. It was compiled sometime during the fourth century in Palestine. The Babylonian Talmud was compiled about the year 500 C.E., although it continued to be edited later. The word "Talmud," when used without qualification, usually refers to the Babylonian Talmud, which is the better known of the two editions.

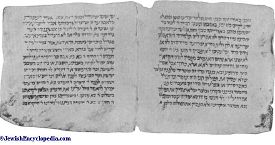

The Jerusalem Talmud

The Jerusalem Talmud originated in Tiberias in the School of Johanan ben Nappaha. It is a compilation of teachings of the rabbinical schools of Tiberias, Sepphoris and Caesarea. It is written in both Hebrew and a western Aramaic dialect that differs from its Babylonian counterpart.

Its final redaction probably belongs to the end of the fourth century, but the individual scholars who brought it to its present form cannot be fixed with assurance. By this time Christianity had become the state religion of the Roman Empire and Jerusalem, the holy city of Christendom. The text is evidently incomplete and is not easy to follow. Any further work on the Jerusalem Talmud probably came to an abrupt end in 425 C.E., when Theodosius II suppressed the Jewish Patriarchate and put an end to the practice of formal scholarly ordination in the Jewish community.

Despite this, the Jerusalem Talmud remains an indispensable source of knowledge regarding the development of the Jewish Law in the Holy Land. Opinions based on the Jerusalem Talmud ultimately found their way into both the Tosafot and the Mishneh Torah of Maimonides.

The Babylonian Talmud

Since the Babylonian Exile of 586 B.C.E., Jews had been living in settlements outside of Judea, and most of the captives did not return home to Jerusalem when this was finally allowed. After the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 C.E. and the later failure of the Bar Kochba revolt, many more Jews moved east. The most important of the Jewish centers were Nehardea, Nisibis, Mahoza, Pumbeditha and Sura.

Talmud Bavli (the "Babylonian Talmud") includes the Mishnah and the Babylonian Gemara. This Gemara is a synopsis of more than 300 years of analysis of the Mishnah in the Babylonian academies.

The man who laid the foundations for the Babylonian Talmud was known simply as Rab, a disciple of Rabbi Judah ha-Nasi, the compiler of the Mishnah. Rabbi Ashi was president of the Sura academy from 375 to 427 C.E. The work begun by Ashi was completed by Rabina. According to ancient tradition, Rabina was the final amoraic expounder. His death in 499 C.E. marked the completion of the redaction of the Talmud.

The question as to when the Gemara was finally put into its present form is not settled among modern scholars. Some of the text did not reach its final form until around 700 C.E.

Comparing the two Talmuds

There are significant differences between the two Talmud compilations. The language of the Jerusalem Talmud is primarily a western Aramaic dialect which differs from that of the Babylonian. The Talmud Yerushalmi is also often fragmentary and difficult to read, even for experienced Talmudists. The redaction of the Talmud Bavli, on the other hand, is more careful and precise.

In the Bavli, however, Gemara exists only for 37 out of the 63 tractates of the Mishnah. Many agricultural ritual purity laws having to do with the Temple had little practical relevance in Babylonia and were therefore not included. The Yerushalmi, though, covers a number of these chapters.

The influence of the Babylonian Talmud has been far greater than that of the Yerushalmi. This is mainly because the influence and prestige of the Jewish community of Palestine steadily declined in contrast with the Babylonian community in the years after the redaction of the Talmud, as Jews in the Islamic lands received much better treatment than they did in the later Christian Empire.

Commentary and study

From the time of its completion, the Talmud became integral to Jewish scholarship. The earliest post-Gemara Talmud commentaries were written by the Gaonim‚ÄĒthe presidents of the rabbinical academies‚ÄĒ(approximately 800-1000 C.E.) in Babylonia.

Early commentators such as Rabbi Isaac Alfasi (North Africa, 1013-1103) attempted to extract and determine the binding legal opinions from the vast corpus of the Talmud. Alfasi's work was highly influential and later served as a basis for the creation of halakhic codes. Another influential medieval halakhic commentary was that of Rabbi Asher ben Yechiel (d. 1327). A fifteenth-century Spanish rabbi, Jacob ibn Habib (d. 1516), composed the En Yaaqob. En Yaaqob (or Ein Yaaqov) extracts nearly all the aggadic material from the Talmud. It was intended to familiarize the public with the ethical parts of the Talmud and to dispute many of the accusations surrounding its contents.

Besides halakhic studies, another major area of talmudic scholarship developed in order to explain these passages and words. Some early commentators such as Rabbenu Gershom of Mainz (tenth century) and Rabbenu Hananel (early eleventh century) produced running commentaries to various tractates. These commentaries could be read with the text of the Talmud and would help explain the meaning of the text. Another important work is the Sefer ha-Mafteach (Book of the Key) by Nissim Gaon, which contains a preface explaining the different forms of talmudic argumentation and then explains abbreviated passages in the Talmud by referring to parallel passages where the same thought is expressed in full. Using a different style, Rabbi Nathan b. Jechiel created a lexicon called the Arukh in the eleventh century in order to translate difficult words.

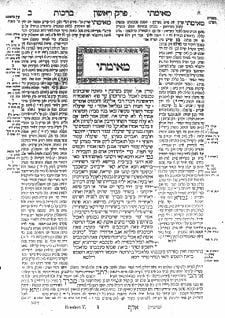

By far the most well known commentary on the Babylonian Talmud is that of Rashi (Rabbi Solomon ben Isaac, 1040-1105). Rashi's commentary is comprehensive, covering almost the entire Talmud. It is considered indispensable to students of the Talmud and is included as a running commentary in modern editions. Maimonides' commentary on the Mishnah, though limited in scope compared to Rahsi's, exerted a similarly great influence.

Medieval Ashkenazic Jewry produced another major commentary known as Tosafot ("additions" or "supplements"). The Tosafot are collected commentaries by various medieval Ashkenazic rabbis on the Talmud. One of the main goals of the Tosafot is to explain and interpret contradictory statements in the Talmud. Unlike Rashi, the Tosafot is not a running commentary, but rather comments on selected matters. Often the explanations of Tosafot differ from those of Rashi.

Over time, the approach of the tosafists spread to other Jewish communities, particularly that of the Sephardic communities in Spain. This led to the composition of many other commentaries in similar styles. Among these are the commentaries of Ramban, Rashba, Ritva, Ran, Yad Ramah, and Meiri.

In later centuries, focus partially shifted from direct talmudic interpretation to the analysis of previously written talmudic commentaries. These later commentaries include "Maharshal" (Solomon Luria), "Maharam" (Meir Lublin) and "Maharsha" (Samuel Edels).

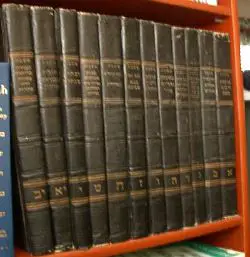

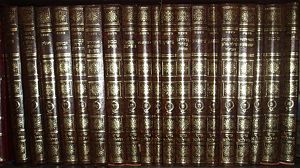

Printing

The first complete edition of the Babylonian Talmud was printed in Italy by Daniel Bomberg during the sixteenth century. In addition to the Mishnah and Gemara, Bomberg's edition contained the Tosafot, the commentaries of Rashi. Almost all printings since Bomberg have followed the same pagination. In 1835, a new edition of the Talmud was printed by Menachem Romm of Vilna (Vilnius, Lithuania). Known as the Vilna Shas, this edition (and later ones printed by his widow and sons) have become an unofficial standard for Talmud editions. In the Vilna edition of the Talmud there are 5,894 folio pages.

Pilpul

During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, a new intensive form of Talmud study arose. Complicated logical arguments were used to explain minor points of contradiction within the Talmud. The term pilpul, which means "pepper" in Hebrew and was applied to this type of study, which hearkens back to the Talmudic era and refers to the intellectual sharpness this method demanded. Pilpul practitioners posited that the Talmud could contain no redundancy or contradiction whatsoever. New categories and distinctions were therefore created, resolving seeming contradictions within the Talmud by novel logical means.

Pilpul study reached its height in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries when expertise in pilpulistic analysis was considered an art form and became a goal in and of itself within the yeshivot (schools) of Poland and Lithuania. However, many sixteenth- and seventeenth-century rabbis were also critical of pilpul. Among them may be noted Judah Loew b. Bezalel (the Maharal), Isaiah Horowitz, and Jair Hayyim Bacharach.

By the eighteenth century, pilpul study waned. Instead, other styles of learning such as that of the school of Elijah b. Solomon, the Vilna Gaon, became popular.

Brisker method

In the late nineteenth century another trend in Talmud study arose. Rabbi Hayyim Soloveitchik (1853-1918) of Brisk (Brest-Litovsk) developed and refined this style of study. The Brisker method involves the analysis of rabbinic arguments within the Talmud, explaining the differing opinions by placing them within a categorical structure. The Brisker method is highly analytical and is often criticized as being a modern-day version of the Pilpul. Nevertheless, the influence of the Brisker method is great. Most modern day yeshivot (Hebrew schools) study the Talmud using the Brisker method in some form. And it is through this method that Maimonides' famous Mishneh Torah began to be read not only as a halakhic work but also as a work of general talmudic interpretation.

Critical method

The text of the Talmud has been subject to some level of critical scrutiny throughout its history.[1] In general, however, traditional commentaries shied away from textual criticism of talmudic passages. In the late eighteenth century, liberalization of social restrictions against Jews resulted in Judaism undergoing enormous upheaval and transformation. Such movements as Reform Judaism and other secularizing and assimilating trends emerged. During this time, modern methods of textual and historical analysis were applied to the Talmud.

Leaders of the Reform movement, such as Abraham Geiger and Samuel Holdheim, subjected the Talmud to severe scrutiny as part of an effort to break with traditional rabbinic Judaism. In reaction, Orthodox leaders such as Moses Sofer and Samson Raphael Hirsch rejected modern critical methods of Talmud study. The methods and manner of Talmud study were thus caught in the debate between the Reformers and Orthodoxy. A middle ground was developed by scholars who believed that, while tampering with Jewish law should be avoided, traditional Jewish sources such as the Talmud should be subject to academic inquiry and critical analysis. Exponents of this view were Zecharias Frankel, Leopold Zunz and Solomon Judah Leib Rappaport.

Because the modern method of historical study had its origins in the era of religious reform, the method was immediately controversial within the Orthodox world. Still, many of the nineteenth century's strongest critics of Reform, including strictly Orthodox rabbis, utilized this new scientific method. Notable among them were Nachman Krochmal and Zvi Hirsch Chajes.

External attacks

Suppression

The history of the Talmud reflects in part the history of Judaism persisting in a world of hostility and persecution. The charge against the Talmud brought by the convert Nicholas Donin in 1244 led to the first burning of copies of the Talmud in Paris. The Talmud was likewise the subject of a disputation at Barcelona in 1263 between Nahmanides (Rabbi Moses ben Nahman) and the convert Pablo Christiani. Criticizing the Talmud's Oral Law tradition as a heresy against the Bible, Christiani's attacks also resulted in a papal bull against the Talmud and in the Dominican censorship commission, which ordered the cancellation of passages reprehensible from a Christian perspective (1264).

At the disputation of Tortosa in 1413, Geronimo de Santa Fé brought forward a number of accusations, including the fateful assertion that the condemnations of pagans and apostates found in the Talmud referred in reality to Christians. Two years later, Pope Martin V, who had convened this disputation, issued a bull forbidding the Jews to read the Talmud, and ordering the destruction of all copies of it. Thankfully, this order was not implemented. Far more important were the charges made in the early part of the sixteenth century by the convert Johannes Pfefferkorn, the agent of the Dominicans whose efforts succeeded in forcing the Jews in several areas to surrender the talmudic books in their possession.

The affair resulted in an investigation which proved some of Pfefferkorn's allegations to be irresponsible. Under the protection of a papal privilege, the complete printed edition of the Babylonian Talmud was issued in 1520 by Daniel Bomberg in Venice. Three years later, in 1523, Bomberg published the first edition of the Jerusalem Talmud. Yet, 30 years after the Vatican permitted the Talmud to appear in print, it undertook a campaign of destruction against it. On September 9, 1553, copies of the Talmud which had been confiscated in compliance with a decree of the Inquisition were burned in Rome; and similar burnings took place in other Italian cities, as at Cremona in 1559. Censorship of the Talmud and other Hebrew works was introduced by a papal bull issued in 1554; five years later the Talmud was included in the first Index Expurgatorius‚ÄĒthe Vatican's list of forbidden books. Pope Pius IV commanded in 1565 that the Talmud be deprived of its very name.

The first edition of the expurgated Talmud, on which most subsequent editions were based, appeared at Basel (1578-1581) with the omission of passages considered inimical to Christianity, together with modifications of certain phrases. A fresh attack on the Talmud was decreed by Pope Gregory XIII (1575-85), and in 1593 Clement VIII renewed the old interdiction against reading or owning it. However, the increasing study of the Talmud in Poland led to the issue of a complete edition (Kraków, 1602-5), with a restoration of the original text. In 1707, copies of the Talmud were confiscated in the province of Brandenburg, but were restored to their owners by command of Frederick, the first king of Prussia. The last attack on the Talmud took place in Poland in 1757, when Bishop Dembowski convened a public disputation at Kamenetz-Podolsk, and ordered all copies of the work found in his bishopric to be confiscated and burned by the hangman.

Anti-Jewish criticism

The external history of attacks against the Talmud also includes the literary attacks made upon it by Christian theologians after the Reformation. Martin Luther and other Reformation theologians harshly criticized Jews and Judaism, and many of these attacks were based on the Talmud.

Later, in 1830, during a debate in the French Chamber of Peers regarding state recognition of the Jewish faith, Admiral Verhuell declared himself unable to forgive the Jews whom he had met during his travels either for their refusal to recognize Jesus as the Messiah or for their possession of the Talmud. In the same year the Abb√© Luigi Chiarini published in Paris a voluminous work entitled Th√©orie du Juda√Įsme, advocating for the first time that the Talmud should be generally accessible, not to serve the Jewish community, but to serve for attacks on Judaism. In a like spirit, modern anti-Semitic agitators have urged that a translation be made. The Talmud and the "Talmud Jew" thus became objects of anti-Semitic attacks, although, on the other hand, they were defended by many Christian students of the Talmud.

In fact, the Talmud makes little mention of Jesus directly or the early Christians. There are a number of derogatory quotes about individuals named Yeshu that once existed in editions of the Talmud; these quotes were long ago removed from the main text due to accusations that they referred to Jesus, and are no longer used in Talmud study. However, these removed quotes were preserved through rare printings of lists of errata, known as Hashmatot Hashass ("Omissions of the Talmud"). Some modern editions of the Talmud contain some or all of this material, either at the back of the book, in the margin, or in alternate print.

Role of the Talmud in Judaism

The Talmud is the written record of an oral tradition. It became the basis for many rabbinic legal codes and customs. Not all Jews, in the past and present, have accepted the Talmud as having religious authority. This section briefly outlines such movements.

Sadducees

The Sadducees were a Jewish sect which flourished during the second temple period. One of their main arguments with the Pharisees (the precursors of Rabbinic Judaism) was over their rejection of an Oral Law. The Sadducees rejected the idea of the Oral Torah and insisted that only the five Books of Moses were authoritative. They also were less likely to accept the authority of some of the prophets and other biblical writings, especially those dealing with such topics as the resurrection of the dead. Because they were largely associated with the Temple priesthood, the Sadducees influence rapidly diminished after the destruction of the Temple in 70 C.E.

Karaism

Another movement which rejected the Oral Law was Karaism. It arose within two centuries of the completion of the Talmud. Karaism developed as a reaction against the Talmudic Judaism of Babylonia. The central concept of Karaism is the rejection of the Oral Torah‚ÄĒand therefore of rabbinical authority‚ÄĒas embodied in the Talmud, in favor of a strict adherence to the Written Law only. Karaism was once a major movement, but has diminished in recent centuries, declining from a high of nearly 10 percent of the Jewish population to a current estimated .002 percent.

Reform Judaism

With the rise of Reform Judaism, during the nineteenth century, the authority of the Talmud was again questioned. The Talmud was seen (together with the Written Law as well) as being a product of antiquity and of having limited relevance to modern Jews. Reform Judaism does not emphasize the study of Talmud to nearly the same degree in their Hebrew schools as do other forms of contemporary Judaism, but the Talmud is indeed studied in Reform rabbinical seminaries.

Orthodox Judaism

Orthodox Judaism continues to stress the importance of Talmud study and it is a central component of Yeshiva curriculum. The regular study of the Talmud among laymen has been popularized by the Daf Yomi, a daily course of Talmud study initiated by Rabbi Meir Shapiro in 1923. Traditional rabbinic education continues to lay heavy emphasis on the knowledge of Talmud.

Conservative Judaism

Conservative Judaism similarly emphasizes the study of Talmud within its religious and rabbinic education. Generally, however, the Talmud is studied as a historical source-text for Halakha. The Conservative approach to legal decision-making emphasizes placing classic texts and prior decisions in historical and cultural context, and examining the historical development of Halakha. This approach has resulted in greater practical flexibility than that of the Orthodox.

Secular Judaism

Many Jews today define themselves as Jews only in an ethnic or cultural sense. These Jews reject the tenets of Jewish religion outright, defining themselves either as agnostics or atheists. Included in the latter category are Jewish Marxists and Marxist-Leninists, who take a militantly atheistic stance, believing that religion itself is primarily a tool of economic oppression.

Translations

Talmud Bavli

There are five contemporary translations of the Talmud into English:

- Tractate Beitzah: The Schottenstein Edition of the Talmud. In this translation, each English page faces the Aramaic/Hebrew page. The English pages are elucidated and heavily annotated; each Aramaic/Hebrew page of Talmud typically requires three English pages of translation.[2]

- The Soncino Talmud, Isidore Epstein. Notes on each page provide additional background material. This translation is published both on its own and in a parallel text edition, in which each English page faces the Aramaic/Hebrew page. It also exists on CD-ROM.[3]

- The Talmud of Babylonia. An American Translation, Jacob Neusner, Tzvee Zahavy, others. Scholars Press, 1984. ISBN 9780891307396

- The Talmud: The Steinsaltz Edition, Adin Steinsaltz. This work is in fact a translation of Rabbi Steinsaltz' Hebrew language translation of and commentary on the entire Talmud.[4]

- The Babylonian Talmud, translated by Michael L. Rodkinson, Randon House (incomplete). This ten volume translation (1918) is also available on the internet.[5] A more current version also available.[6]

Talmud Yerushalmi

- The Yerushalmi‚ÄĒThe Talmud of the Land of Israel: A Preliminary Translation and Explanation, Jacob Neusner.[7]

- Schottenstein Edition of the Yerushalmi Talmud Mesorah/Artscroll. This translation is the counterpart to Mesorah/Artscroll's Schottenstein Edition of the Babylonian Talmud). [8]

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ One of Rashi's major accomplishments was textual correction. Some tosafists, too, amended the talmudic text (for example, Baba Kamma 83b s.v. af haka'ah ha'amurah or Gittin 32a s.v. mevutelet) as did many other medieval commentators (for example, R. Shlomo ben Adrat, Hidushei ha-Rashb"a al ha-Sha"s to Baba Kamma 83b, or Rabbenu Nissim's commentary to Alfasi on Gittin 32a).

- ‚ÜĎ Ysiroel Reisman, Tractate Beitzah: The Schottenstein Edition (Mesorah Publications, 1992, ISBN 9780899067308).

- ‚ÜĎ Isidore Epstein (ed.), Soncino Hebrew/English Babylonian Talmud (Bnpublishing.com; CD-ROM edition, 2005, ISBN 9568351140).

- ‚ÜĎ Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz, The Talmud, The Steinsaltz Edition (Random House, 1999, ISBN 9780375503504).

- ‚ÜĎ Michael L. Rodkinson (trans.), The Babylonian Talmud [1918]. Internet Sacred Text Archive. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- ‚ÜĎ Michael L. Rodkinson, The Babylonian Talmud: Tract Sanhedrin (Kessinger Publishing, 2004, ISBN 1419153420).

- ‚ÜĎ Jacob Neusner, The Yerushalmi‚ÄĒThe Talmud of the Land of Israel: An Introduction (Jason Aronson Press, 1994, ISBN 9780876688120).

- ‚ÜĎ Rabbi Nosson Scherman and Rabbi Meir Zlotowitz (eds.), Schottenstein Edition Talmud Yerushalmi: Tractate Berachos (Mesorah Publications, 2005, ISBN 9781422602348).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carmell, Aryeh. Aiding Talmud Study. Feldheim, 5th ed., 1986. ISBN 978-0873064286

- Herford, R. Travers. Christianity in Talmud and Midrash. Ktav Pub. Inc., 1975. ISBN 0870684833

- Lampel, Zvi. Maimonides' Introduction to the Commentary on the Mishnah. Judaica Press, 1998. ISBN 1880582287

- Landesman, D. A Practical Guide to Torah Learning. Jason Aronson, 1995. ISBN 1568213204

- Neusner, Jacob. Sources and Traditions: Types of Compositions in the Talmud of Babylonia. University of South Florida, 1992. ISBN 1555406750

- Parry, Aaron. The Complete Idiot's Guide to The Talmud. Alpha Books, 2004. ISBN 1592572022

- Steinsaltz, Adin. The Talmud, The Steinsaltz Edition: A Reference Guide. Random House, 1996. ISBN 0679773673

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- Talmud Jewish Encyclopedia

- Talmud Commentaries Jewish Encyclopedia

- Judaism History: Talmud

- Judaism: The Oral Law -Talmud & Mishna Jewish Virtual Library

- A Page from the Babylonian Talmud

- Falsifiers of the Talmud

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.