Sarah

Sarah (Hebrew שָׂרָה ; Arabic سارة, Saara ; "a woman of high rank") was a great woman of faith and the fore-mother of the Israelites as described the Hebrew Bible. Sarah's story is told in the Book of Genesis. She was the wife of Abraham, mother of Isaac, and grandmother of Jacob. She traveled with Abraham from Haran to Canaan and later spent time in the harems of two kings in order to protect her husband. Like several other important biblical women, Sarah had been barren, prompting her to offer her slave Hagar to her husband to bear him a child. Later, at the age of 90, a miracle allowed her to conceive and give birth to her own providential son: Isaac. She is also known for her rejection of Hagar and her son, Ishmael. Sarah reportedly lived to be 127 and is traditionally believed to be buried with her husband and descendants in the Cave of the Patriarchs at Hebron.

Hebrew Bible

Journeys

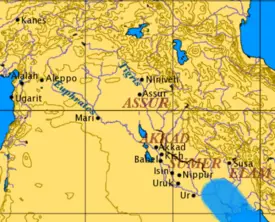

Sarah was originally called Sarai. She was born in the major Mesopotamian city of Ur and moved with her clan to Haran, where she lived with her husband, then called Abram. Like several other great biblical women, Sarai could not have children. However, God promised Abram that he would become a father of multitudes, instructing him to leave Haran and journey to an unknown land (later identified as Canaan). Sarai accompanied him on this journey, along with their nephew Lot and a number of slaves. In Canaan, they stayed long enough to establish two altars at sites which later became Israelite religious centers, one at Shechem, the other at Bethel. However, a famine threatened, and Abram decided that the clan should take refuge in Egypt.

Arriving in Egypt, Abram feared that Sarai's beauty would put his life in danger if their true relationship became known. He proposed that she pass as his sister. "I will be treated well for your sake, and my life will be spared because of you," he told her. Risking her own life as well as her chastity, Sarai agreed to this plan and was taken into Pharaoh's harem. The king rewarded Abram richly on her account. However, God struck Pharaoh and his household with severe diseases, after which the king suspected the truth. He censured Abram and ordered him to take his wife and depart. Sarai, Abram, and Lot took with them the considerable wealth that the king had presented them in livestock, slaves, and other possessions. According to a later rabbinical tradition, Pharaoh also sent his own daughter, Hagar, to be Sarai's slave.

Settling in Canaan

The couple, now very wealthy, journeyed back to Bethel. There, Abram ordered Lot—who also possessed a great many flocks—to separate from the rest of the clan due to quarrels between their herdsmen. Lot fatefully chose to take his herds toward the well-watered plain of the Jordan and from there south to Sodom, while Sarai and Abram remained in the hill country of Canaan. Abram led his flocks to the area of Mamre, near Hebron, where he established yet another altar to his God.

Meanwhile, although God again promised Abram that he would yet be a father of nations, Sarai remained childless after ten more years in Canaan. To help her husband fulfill his destiny, she offered her Egyptian slave, Hagar, to him for sexual intercourse, saying "perhaps I can build a family through her" (Gen. 16:2). Hagar quickly became pregnant and began to despise and taunt her mistress. Sarai bitterly complained to her husband, but Abram responded that she should do with her slave as she deemed best. Sarai's harsh treatment of Hagar forced the handmaid to flee to the desert. There, the angel of God met her and commanded her to return to Sarah and submit to her. The angel also announced that although Hagar's son would be "a wild donkey of a man," her descendants would be "too numerous to count." (Gen. 15:10) After Hagar returned, she bore a son whom Abram named Ishmael.

When God then established the covenant of circumcision with Abram's family, he changed the couple's names to Abraham and Sarah. Soon, three mysterious men visited the couple at Mamre. Sarah baked bread for the strangers, while Abraham brought both meat and milk dishes. The strangers, referred to by the narrator as "the Lord" (Yahweh), told Abraham that Sarah, despite being 90, would soon bear a son. Overhearing the prophecy, Sarah laughed at the idea, thinking, "After I am worn out and my master is old, will I now have this pleasure?" (Gen. 18:11).

Abraham then moved his people and flocks to Gerar, a Philistine city. Sarah, once more posing as Abraham's sister, was again taken into the king's household—this time, the king being Abimelech. Warned by God in a dream not to touch Sarah, Abimelech returned Sarah to Abram with rich gifts. Here we learn that the tale of her being Abraham's sister is not entirely false, for Sarah was in fact her husband's half-sister (Gen. 20:1-12).

The Birth of Isaac

Having reunited with Abraham after her time in Abimelech's house, Sarah soon became pregnant. Probably in Beersheba, she gave birth to a healthy son named Isaac, meaning "he laughed," declaring: "God has brought me laughter, and everyone who hears about this will laugh with me." (Gen. 21:7)

Sarah nursed the child, and he grew into a healthy toddler. When it came time to wean him, Abraham gave a feast to celebrate the event. However, Sarah noticed Ishmael playing with the lad in a way that disturbed her. She immediately went to Abraham and demanded: "Get rid of that slave woman and her son, for that slave woman's son will never share in the inheritance with my son Isaac." Abraham balked at this idea, but the biblical narrative tells us that God sided with Sarah in the matter, saying:

“Do not be so distressed about the boy and your maidservant. Listen to whatever Sarah tells you, because it is through Isaac that your offspring will be reckoned. I will make the son of the maidservant into a nation also, because he is your offspring." (Gen. 21:12-13)

While artists traditionally portray Isaac and Ishmael as playmates of nearly the same age, rabbinical tradition sees Ishmael as already an adolescent by this time. Thus Sarah is seen as having legitimate fears for Isaac's physical and spiritual safety (see below).

After the near-sacrifice of Isaac by Abraham, Sarah died in Hebron, at the age of 127 years. Her death prompted Abraham to purchase a family burial plot, and he approached Ephron the Hittite to sell him the Cave of Machpelah (now called the Cave of the Patriarchs). Ephron demanded a huge price of four hundred pieces of silver, which Abraham paid in full. The Cave of Machpelah would eventually be the burial site for all three Jewish patriarchs and three of the four matriarchs: Abraham and Sarah, Isaac and Rebekah, and Jacob and Leah.

No further reference to Sarah is found in the Hebrew canon, except in Isaiah 51:2, where the prophet appeals to his hearers to "look unto Abraham your father, and unto Sarah that bare you." It is no exaggeration to say that in the biblical tradition, Sarah was—both physically and spiritually—the grandmother of the Israelites.

Sarah in Rabbinic Literature

The rabbis make much of Sarah's beauty. She was so beautiful that all other people seemed like apes in comparison (Talmud, Bava Batra 58a). According to another tradition, she had prophetic vision (Meg. 50c). Indeed, she was superior to Abraham in the gift of prophecy. She was the "crown" of her husband; he obeyed her words because he recognized her superiority (Gen. Rabbah 47:1). She was the only woman whom God deemed worthy to be addressed by Him directly, all the other prophetesses receiving their revelations through angels (ibid. 45:14). On their journeys Abraham converted the men, and Sarah the women (ibid. 39:21).

On meeting the pharaoh, it was Sarah, not Abraham, who said that Abraham was her brother (Sefer ha-Yashar 40c). The king deeded his entire estate to her and gave her the land of Goshen as her hereditary possession. This was the reason the Israelites subsequently lived in that land (Pirke R. El. 36). The slave girl Hagar was in reality the king's own daughter (ibid.) Sarah prayed to God to deliver her from the king, and God responded by smiting Pharaoh whenever he attempted to touch her.

Sarah treated Hagar kindly for ten years. But when Hagar became pregnant by Abraham, Hagar provoked her. Sarah imposed heavy work upon Hagar, and did indeed strike her (Pirke R. El. 45:9). After Sarah gave birth to Isaac, people doubted this miracle and suspected that the old couple had merely adopted a foundling. This prompted Abraham to hold a large feast in Isaac's honor, at which Sarah proved her motherhood by nursing all the children present. Sarah's rejection of Ishmael is justified by the rabbis not primarily on the grounds of his arrogance toward Isaac during the feast, but because he threatened the boy's life. Moreover, she personally saw him commit the three greatest sins: idolatry, unchastity, and murder (Gen. R. 53:15).

In one rabbinical legend, Sarah actually died of grief, believing that Abraham had carried out the sacrifice of Isaac while the two of them were gone from her (Pirke R. El. 32). In another, she responded to the news of the sacrifice (delivered by Satan) in faith, believing it to be the will of God. She then went in search of Abraham and died at Hebron in a joyful state (Gen. R. 50:15).[1]

Critical View

Like Abraham, Sarah is viewed by bible critics as being at least as much a legendary figure as an historical person. Even the location of Ur "of the Chaldeans" is disputed, with an alternative location suggested in present-day Turkey rather than southern Iraq.

Also, the biblical text presents several inconsistencies, leaps, and repetitions. The incident with Pharaoh (Gen. 12) is so similar to the story of Sarah and Abimelech (Gen. 20) as to suggest that the two tales represent two versions of the same story. According to the documentary hypothesis, the first is thought to be from the "J" source, which calls God Yahweh/Jehovah; the second from the "E" source in which God is called Elohim (in English, these two names are normally translated "The Lord" and "God," respectively). Similarly, the story in Genesis 18 of Sarah laughing at the idea of conceiving a son (from the "J" source) is mirrored by that of Abraham doing the same a few verses earlier (in a story from the "E" source). Likewise, the "J" story of Hagar's escape to the desert in Genesis 16 can be seen as a variant of the "E" story of Hagar's expulsion into the desert in Genesis 21. Some view the name "Sarai" as the "E" variant of the name that "J" uses—"Sarah" (the latter containing a "Yah" sound at its end). The story of God's renaming the couple in this theory was the creation of a later teller of the couple's tale. According to Exodus 6:3 the couple worships El Shaddai and does not yet even know that name of Yahweh, while in the "J" source, they "call upon the name of the Lord." The text also contains several other anachronisms, from the title "pharaoh" for the king of Egypt (a title was not yet used in Sarah's time) to the presence of a Philistine king (Abimelech) in Gerar at a time when archaeologists believe these Sea People had not yet arrived in the area.

Scholars are anything but unanimous regarding the historical value of the saga of Sarah and Abraham. For example some point to the fact that marriages between half-siblings were common among noble families during the period, seeing this as evidence for an historical basis of the story, especially given the fact that such marriages are expressly forbidden in the Mosaic Law. So too, the tradition of an infertile wife giving a slave to her husband is consistent with ancient Mesopotamian practice.

Counter-veiling theories point out that the patriarchal stories represent older Canaanite, pre-Israelite material, adopted and adapted later by Israelite tradition. Sarah herself is sometimes seen as a type of Ishtar figure rewritten into Israelite monotheistic culture. Finally, genealogies such as those in the patriarchal story are seen not relating to historical individuals so much as to clans. Accordingly, Sarah, as well as many of the other patriarchal and matriarchal figures, is considered to be representatives of a proto-Israelite clan that eventually federated into the nation of Israel.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bloom, Harold. The Book of J. Grove Press, 2005. ISBN 0802141919

- Fischbein, Jessie. Infertility in the Bible: How The Matriarchs Changed Their Fate; How You Can Too. Devora Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-1932687347

- Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. Reading the Women of the Bible: A New Interpretation of Their Stories. Schocken, 2002. ISBN 978-0805241211

- Halter, Marek. Sarah: A Novel (Canaan Trilogy). Crown, 2004. ISBN 978-1400052721

- Kirsch, Jonathan. The Harlot by the Side of the Road. Ballantine Books, 1998. ISBN 0345418824

- Midrash Rabbah and other ancient rabbinical commentaries from Sacred-Texts.com.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.