Saladin

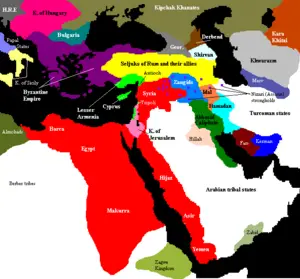

Saladin, Salah ad-Din, or Salahuddin al Ayyubi (so-lah-hood-din al-aye-yu-be) (c. 1138 ‚Äď March 4, 1193), was a twelfth century Kurdish Muslim general and warrior from Tikrit, in present-day, northern Iraq. He founded the Ayyubid dynasty of Egypt, Syria, Yemen (except for the Northern Mountains), Iraq, Mecca Hejaz, and Diyar Bakr. Saladin is renowned in both the Muslim and Christian worlds for leadership and military prowess, tempered by his chivalry and merciful nature during his war against the Crusaders. In relation to his Christian contemporaries, his character was exemplary, to an extent that propagated stories of his exploits back to the West, incorporating both myth and facts.

Salah ad-Din is an honorific title which translates to "The Righteousness of the Faith" from Arabic. Saladin is also regarded as a Waliullah, which means the friend of God to the Sunni Muslims.

Summary

Known as the great opponent of the Crusaders, Saladin was a Muslim warrior and Ayyubid sultan of Egypt. Of Kurdish ancestry from Mesopotamia, Saladin lived for ten years in Damascus in the court of Nur ad-Din, where he studied Sunni theology. Later, Saladin went with his uncle, Shirkuh, a lieutenant of Nur ad-Din, on campaigns (1164, 1167, 1168) against the Fatimid rulers of Egypt. Shirkuh became vizier in Egypt, and on his death (1169) was succeeded by Saladin, who later caused the name of the Shiite Fatimid caliph to be excluded from the Friday prayer, thus excluding him from the ruling hierarchy.

With Saladin now a major force, Nur ad-Din planned to campaign against his increasingly powerful subordinate, but after his death, Saladin declared himself sultan of Egypt, thus beginning the Ayyubid dynasty. He conquered the lands westward on the northern shores of Africa as far as Qabis. Saladin also conquered Yemen, took over Damascus, and began conquests of Syria and Palestine. By this time, he had already begun fighting the Crusaders, causing the rulers of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem into fighting from a defensive position. He was unsuccessful in his efforts to conquer the Assassins in their mountain strongholds, but he conquered Mosul, Aleppo, and broad lands from rival Muslim rulers. In doing so, Saladin became Islam’s greatest warrior.

Saladin formed a large Muslim army to fight the Christians. In the famous battle of Hattin (near Tiberius) in 1187, he won a stunning victory, capturing Guy of Lusignan and Reginald of Chatillon. The city of Jerusalem also fell to Saladin, causing the Third Crusade to gather (1189) and come to the Holy Land to try to recover Christendom’s holy city. It was during this campaign that Richard I of England and Saladin met in conflict, establishing a mutual chivalric admiration between the two worthy opponents that became the subject of European legend and lore.

The Crusaders, however, failed in taking back Jerusalem and succeeded only in capturing the fortress of Akko. In 1192 under the Peace of Ramla, Saladin came to an agreement with Richard, leaving Jerusalem in Muslim hands and the Latin Kingdom in possession of only a strip along the coast from Tyre to Joppa. Although Saladin accepted the major concession of allowing Christian pilgrims to enter Jerusalem, the Christians were never to recover from their defeat. Saladin died on March 4, 1193 at Damascus, not long after Richard's departure. His mausoleum there is a major attraction.

Rise to power

Saladin was born in 1138 into a Kurdish family in Tikrit and was sent to Damascus to finish his education. His father, Najm ad-Din Ayyub, was governor of Baalbek. For ten years Saladin lived in Damascus and studied Sunni Theology, at the court of the Syrian ruler Nur ad-Din (Nureddin). He received an initial military education under the command of his uncle Shirkuh, Nur ad-Din's lieutenant, who was representing Nur ad-Din in campaigns against a faction of the Fatimid caliphate of Egypt in the 1160s. Saladin eventually replaced his uncle as vizier of Egypt in 1169.

There, he inherited a difficult role defending Egypt against the incursions of the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem, under Amalric I. His position was tenuous at first. No one expected him to last long in Egypt, where there had been many changes of government in previous years due to competing viziers fighting over the power to rule on behalf of a long line of child caliphs. As the Sunni leader of a foreign army from Syria, Saladin also had little control over the Shi'ite Egyptian army, which was led in the name of the now otherwise powerless Fatimid caliph Al-Adid.

When the caliph died in September 1171, Saladin had the imams, at sermon before Friday prayers, declare the name of Al-Mustadi‚ÄĒthe Abbassid Sunni caliph in Baghdad‚ÄĒin Al-Adid's place. The imams thus recognized a new caliphate line. Now Saladin ruled Egypt, officially as the representative of Nur ad-Din, who recognized the Abbassid caliph.

Saladin revitalized the economy of Egypt, reorganized the military forces and stayed away from any conflicts with Nur ad-Din, his formal lord. He waited until Nur ad-Din's death before starting serious military actions: at first against smaller Muslim states, then against the Crusaders.

With Nur ad-Din's death (1174), Saladin assumed the title of sultan in Egypt. There he declared independence from the Seljuks, and he proved to be the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty and restored Sunnism in Egypt. He extended his territory westwards in the maghreb, and when his uncle was sent up the Nile to pacify some resistance of the former Fatimid supporters, he continued on down the Red Sea to conquer Yemen.

Fighting the Crusaders

On two occasions, in 1171 and 1173, Saladin retreated from an invasion of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. These had been launched by Nur ad-Din, technically Saladin's commander. Saladin apparently hoped that the Crusader kingdom would remain intact as a buffer state between Egypt and Syria, until he could gain control of Syria as well. Nur ad-Din and Saladin were headed towards open war on these counts when Nur ad-Din died in 1174. Nur ad-Din's heir as-Salih Ismail al-Malik was a mere boy, in the hands of court eunuchs, and died in 1181.

Immediately after Nur ad-Din's death, Saladin marched on Damascus and was welcomed into the city. He reinforced his legitimacy there in the time-honored way‚ÄĒby marrying Nur ad-Din's widow. However, Aleppo and Mosul, the two other largest cities that Nur ad-Din had ruled, were never taken. Saladin managed to impose his influence and authority on them in 1176 and 1186, respectively. While he was occupied in besieging Aleppo, on May 22, 1176, the elite, shadowy, assassin group "Hashshashins" attempted to murder him.

While Saladin was consolidating his power in Syria, he usually left the Crusader kingdom alone, although he was generally victorious whenever he did meet the Crusaders in battle. One exception was the Battle of Montgisard on November 25, 1177. He was defeated by the combined forces of Baldwin IV of Jerusalem, Raynald of Chatillon, and the Knights Templar. Only one tenth of his army made it back to Egypt.

A truce was declared between Saladin and the Crusader States in 1178. Saladin spent the subsequent year recovering from his defeat and rebuilding his army, renewing his attacks in 1179 when he defeated the Crusaders at the Battle of Jacob's Ford. Crusader counter-attacks provoked further responses by Saladin. Raynald of Chatillon, in particular, harassed Muslim trading and pilgrimage routes with a fleet on the Red Sea, a water route that Saladin needed to keep open. Raynald threatened to attack the holy cities of Mecca and Medina. In retaliation, Saladin besieged Kerak, Raynald's fortress in Oultrejordain, in 1183 and 1184. Raynald responded by looting a caravan of Muslim Hajj pilgrims in 1185.

In July of 1187, Saladin captured the Kingdom of Jerusalem. On July 4, 1187, he faced at the Battle of Hattin the combined forces of Guy of Lusignan, King consort of Jerusalem, and Raymond III of Tripoli. In the battle alone the Crusader army was largely annihilated by the motivated army of Saladin in what was a major disaster for the Crusaders and a turning point in the history of the Crusades. Saladin captured Raynald de Chatillon and was personally responsible for his execution. (According to the chronicle of Ernoul, Raynald had captured Saladin's supposed sister in a raid on a caravan, although this is not attested to in Muslim sources. According to these sources, Saladin never had a sister, but only mentioned the term when referring to a fellow Muslim who was female.)

Guy of Lusignan was also captured, but his life was spared. Two days after the Battle of Hattin, Saladin ordered the execution of all prisoners of the military monastic orders by beheading. According to the account of Imad al-Din, Saladin watched the executions ‚Äúwith a glad face.‚ÄĚ The execution of prisoners at Hattin was not the first by Saladin. On August 29, 1179, he had captured the castle at Bait al-Ahazon where approximately 700 prisoners were taken and executed.

Soon, Saladin had taken back almost every Crusader city. When he recaptured Jerusalem on October 2, 1187, he ended 88 years of Crusader rule. Saladin initially was unwilling to grant terms of quarter to the occupants of Jerusalem until Balian of Ibelin threatened to kill every Muslim in the city (estimated between 3,000 to 5,000) and to destroy Islam’s holy shrines of the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa Mosque if quarter was not given. Saladin consulted his council, and these terms were accepted. Ransom was to be paid for each Frank in the city whether man, woman, or child. Although Saladin allowed some to leave without paying the required amount for ransom, according to Imad al-Din, approximately 7,000 men and 8,000 women were taken into slavery.

Only Tyre held out. The city was now commanded by the formidable Conrad of Montferrat. He strengthened Tyre's defenses and withstood two sieges by Saladin. In 1188, Saladin released Guy of Lusignan and returned him to his wife Queen regnant Sibylla of Jerusalem. Both rulers were allowed to seek refuge at Tyre, but were turned away by Conrad, who did not recognize Guy as King. Guy then set about besieging Acre.

The defeat at the battle of Hattin and the fall of Jerusalem prompted the Third Crusade, financed in England by a special "Saladin tithe." This Crusade took back Acre, and Saladin's army met King Richard I of England at the Battle of Arsuf on September 7, 1191, where Saladin was defeated. Saladin's relationship with Richard was one of chivalrous mutual respect as well as military rivalry. Both were celebrated in courtly romances. When Richard was wounded, Saladin offered the services of his personal physician. At Arsuf, when Richard lost his horse, Saladin sent him two replacements. Saladin also sent him fresh fruit and snow to keep his drinks cold. Richard, in his turn, suggested to Saladin that his sister marry Saladin's brother‚ÄĒand Jerusalem could be their wedding gift.

The two came to an agreement over Jerusalem in the Treaty of Ramla in 1192, whereby the city would remain in Muslim hands, but would be open to Christian pilgrimages. The treaty reduced the Latin Kingdom to a strip along the coast from Tyre to Jaffa.

Saladin died on March 4, 1193, at Damascus, not long after Richard's departure.

Burial site

Saladin is buried in a mausoleum in the garden outside the Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, Syria, and is a popular attraction. Emperor Wilhelm II of Germany donated a new marble sarcophagus to the mausoleum. Saladin was, however, not placed in it. Instead the mausoleum now has two sarcophagi: one empty in marble and one in wood containing the body of Saladin.

Legacy

Despite his fierce struggle to the Christian incursion, Saladin achieved a great reputation in Europe as a chivalrous knight, so much so that there existed by the fourteenth century an epic poem about his exploits, and Dante included him among the virtuous pagan souls in Limbo. The noble Saladin appears in a sympathetic light in Sir Walter Scott's The Talisman (1825). Despite the Crusaders' acts of slaughter when they originally conquered Jerusalem in 1099, Saladin granted amnesty and free passage to all Catholics and even to the defeated Christian army, as long as they were able to pay the aforementioned ransom. Greek Orthodox Christians were treated even better, because they often opposed the western Crusaders.

The name Salah ad-Din means "Righteousness of Faith," and through the ages Saladin has been an inspiration for Muslims in many respects. Modern Muslim rulers have sought to capitalize on the reputation of Saladin. A governorate centered around Tikrit in modern Iraq, Salah ad Din, is named after Saladin, as is Salahaddin University in Arbil.

Few structures associated with Saladin survive within modern cities. Saladin first fortified the Citadel of Cairo (1175-1183), which had been a domed pleasure pavilion with a fine view in more peaceful times. Among the forts he built was Qalaat Al-Gindi, a mountaintop fortress and caravanserai in the Sinai. The fortress overlooks a large wadi which was the convergence of several caravan routes that linked Egypt and the Middle East. Inside the structure are a number of large vaulted rooms hewn out of rock, including the remains of shops and a water cistern. A notable archaeological site, it was investigated in 1909 by a French team under Jules Barthoux.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ad-Din, Baha (ed.), and D. S. Richards. The Rare and Excellent History of Saladin. Ashgate, 2002. ISBN 978-0754633815

- Bowman, Alan K. Egypt After the Pharaohs: 332 B.C.E.-AD 642: From Alexander to the Arab Conquest. University of California Press; New Ed edition, 1996.

- Gibb, H. A. R. The Life of Saladin: From the Works of Imad ad-Din and Baha ad-Din. Clarendon Press, 1973. ISBN 978-0863569289

- Gillingham, John. Richard I, Yale English Monarchs. Yale University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0300079128

- Lane-Poole, Stanley. Saladin and the Fall of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. Putnam, 1898; 1st Cooper Square Press Ed edition, 2002. ISBN 978-0815412342

- Lyons, M. C., and D. E. P. Jackson, Saladin: the Politics of the Holy War. Cambridge University Press, 1982. ISBN 978-0521317399

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Richard and Saladin: Warriors of the Third Crusade www.shadowedrealm.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.