Difference between revisions of "Abortion" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Claimed}} | + | {{Claimed}}{{Started}} |

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Law]] | [[Category:Law]] | ||

Revision as of 21:40, 7 July 2007

An abortion is the removal or expulsion of an embryo or fetus from the uterus, resulting in or caused by its death. This can occur spontaneously as a miscarriage, or be artificially induced by chemical, surgical or other means. Commonly, "abortion" refers to an induced procedure at any point during human pregnancy; medically, it is defined as miscarriage or induced termination before twenty weeks' gestation, which is considered nonviable.

Throughout history, abortion has been induced by various methods. The moral and legal aspects of abortion are subject to intense debate in many parts of the world.

Definitions

The following medical terms are used to categorize abortion:

- Spontaneous abortion (miscarriage): An abortion due to accidental trauma or natural causes. Most miscarriages are due to incorrect replication of chromosomes; they can also be caused by environmental factors.

- Induced abortion: Abortion that has been caused by deliberate human action. Induced abortions are further subcategorized into therapeutic and elective:

- Therapeutic abortion:[1]

- To save the life of the pregnant woman.

- To preserve the woman's physical or mental health.

- To terminate pregnancy that would result in a child born with a congenital disorder that would be fatal or associated with significant morbidity.

- To selectively reduce the number of fetuses to lessen health risks associated with multiple pregnancy.

- Elective abortion: Abortion performed for any other reason.

- Therapeutic abortion:[1]

In common parlance, the term "abortion" is synonymous with induced abortion. However, in medical texts, the word 'abortion' might exclusively refer to, or may also refer to, spontaneous abortion (miscarriage).

Incidence

The incidence and reasons for induced abortion vary regionally. It has been estimated that approximately 46 million abortions are performed worldwide every year. Of these, 26 million are said to occur in places where abortion is legal; the other 20 million happen where the procedure is illegal. Some countries, such as Belgium (11.2 per 100 known pregnancies) and the Netherlands (10.6 per 100), have a low rate of induced abortion, while others like Russia (62.6 per 100) and Vietnam (43.7 per 100) have a comparatively high rate. The world ratio is 26 induced abortions per 100 known pregnancies.[2]

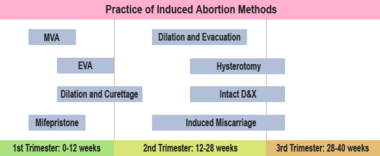

By gestational age and method

Abortion rates also vary depending on the stage of pregnancy and the method practiced. In 2003, from data collected in those areas of the United States that sufficiently reported gestational age, it was found that 88.2% of abortions were conducted at or prior to 12 weeks, 10.4% from 13 to 20 weeks, and 1.4% at or after 21 weeks. 90.9% of these were classified as having been done by "curettage" (suction-aspiration, D&C, D&E), 7.7% by "medical" means (mifepristone), 0.4% by "intrauterine instillation" (saline or prostaglandin), and 1.0% by "other" (including hysterotomy and hysterectomy).[3] The Guttmacher Institute estimated there were 2,200 intact dilation and extraction procedures in the U.S. during 2000; this accounts for 0.17% of the total number of abortions performed that year.[4] Similarly, in England and Wales in 2005, 90% of terminations occurred at or under 12 weeks, 9% between 13 to 19 weeks, and 1% at or over 20 weeks. 71% of those reported were by vacuum aspiration, 5% by D&E, and 24% were medical.[5]

By personal and social factors

A 1998 aggregated study, from 27 countries, on the reasons women seek to terminate their pregnancies concluded that common factors cited to have influenced the abortion decision were; desire to delay or end childbearing, concern over the interruption of work or education, issues of financial or relationship stability, and perceived immaturity.[6] A 2004 study in which American women at clinics answered a questionnaire yielded similar results.[7] In Finland and the United States, concern for the health risks posed by pregnancy in individual cases was not a factor commonly given; however, in Bangladesh, India, and Kenya health concerns were cited by women more frequently as reasons for having an abortion.[6] 1% of women in the 2004 survey-based U.S. study became pregnant as a result of rape and 0.5% as a result of incest.[7] Another American study in 2002 concluded that 54% of women who had an abortion were using a form of contraception at the time of becoming pregnant while 46% were not. Inconsistent use was reported by 49% of those using condoms and 76% of those using oral contraception; 42% of those using condoms reported failure through slipping or breakage.[8]

Some abortions are undergone as the result of societal pressures. These might include the stigmatization of disabled persons, preference for children of a specific sex, disapproval of single motherhood, insufficient economic support for families, lack of access to or rejection of contraceptive methods, or efforts toward population control (such as China's one-child policy). These factors can sometimes result in compulsory abortion or sex-selective abortion. In many areas, especially in developing nations or where abortion is illegal, women sometimes resort to "back-alley" or self-induced procedures. The World Health Organization suggests that there are 19 million terminations annually which fit its criteria for an unsafe abortion.[9] See social issues for more information on these subjects.

Forms of abortion

Spontaneous abortion

Spontaneous abortions, generally referred to as miscarriages, occur when an embryo or fetus is lost due to natural causes before the 20th week of gestation. A pregnancy that ends earlier than 37 weeks of gestation, if it results in a live-born infant, is known as a "premature birth." When a fetus dies in the uterus at some point late in gestation, beginning at about 20 weeks, or during delivery, it is termed a "stillbirth." Premature births and stillbirths are generally not considered to be miscarriages although usage of these terms can sometimes overlap.

Most miscarriages occur very early in pregnancy. Between 10% and 50% of pregnancies end in miscarriage, depending upon the age and health of the pregnant woman.[10] In most cases, they occur so early in the pregnancy that the woman is not even aware that she was pregnant.

The risk of spontaneous abortion decreases sharply after the 8th week.[11] This risk is greater in those with a known history of several spontaneous abortions or an induced abortion, those with systemic diseases, and those over age 35. Other causes can be infection (of either the woman or fetus), immune response, or serious systemic disease. A spontaneous abortion can also be caused by accidental trauma; intentional trauma to cause miscarriage is considered induced abortion or feticide.

Induced abortion

A pregnancy can be intentionally aborted in many ways. The manner selected depends chiefly upon the gestational age of the fetus, in addition to the legality, regional availability, and doctor-patient preference for specific procedures.

Surgical abortion

In the first twelve weeks, suction-aspiration or vacuum abortion is the most common method.[12] Manual vacuum aspiration, or MVA abortion, consists of removing the fetus or embryo by suction using a manual syringe, while the Electric vacuum aspiration or EVA abortion method uses an electric pump. These techniques are comparable, differing in the mechanism used to apply suction, how early in pregnancy they can be used, and whether cervical dilation is necessary. MVA, also known as "mini-suction" and menstrual extraction, can be used in very early pregnancy, and does not require cervical dilation. Surgical techniques are sometimes referred to as STOP: 'Suction (or surgical) Termination Of Pregnancy'. From the fifteenth week until approximately the twenty-sixth week, a dilation and evacuation (D & E) is used. D & E consists of opening the cervix of the uterus and emptying it using surgical instruments and suction.

Dilation and curettage (D & C) is a standard gynecological procedure performed for a variety of reasons, including examination of the uterine lining for possible malignancy, investigation of abnormal bleeding, and abortion. Curettage refers to cleaning the walls of the uterus with a curette. The World Health Organization recommends this procedure, also called Sharp Curettage, only when MVA is unavailable.[13] The term "D and C," or sometimes suction curette, is used as a euphemism for the first trimester abortion procedure, whichever the method used.

Other techniques must be used to induce abortion in the third trimester. Premature delivery can be induced with prostaglandin; this can be coupled with injecting the amniotic fluid with caustic solutions containing saline or urea. Very late abortions can be induced by intact dilation and extraction (IDX) (also called intrauterine cranial decompression), which requires surgical decompression of the fetus's head before evacuation. IDX is sometimes termed as "partial-birth abortion." A hysterotomy abortion, similar to a caesarian section but resulting in a terminated fetus, can also be used at late stages of pregnancy. It can be performed vaginally, with an incision just above the cervix, in the late mid-trimester.[citation needed]

From the 20th to 23rd week of gestation, an injection to stop the fetal heart can be used as the first phase of the surgical abortion procedure.[14]

Medical abortion

Effective in the first trimester of pregnancy, medical (sometimes called chemical abortion), or non-surgical abortions comprise 10% of all abortions in the United States and Europe. Combined regimens include methotrexate or mifepristone, followed by a prostaglandin (either misoprostol or gemeprost: misoprostol is used in the U.S.; gemeprost is used in the UK and Sweden.) When used within 49 days gestation, approximately 92% of women undergoing medical abortion with a combined regimen completed it without surgical intervention.[15] Misoprostol can be used alone, but has a lower efficacy rate than combined regimens. In cases of failure of medical abortion, vacuum or manual aspiration is used to complete the abortion surgically.

Other means of abortion

Historically, a number of herbs reputed to possess abortifacient properties have been used in folk medicine: tansy, pennyroyal, black cohosh, and the now-extinct silphium (see history of abortion).[16] The use of herbs in such a manner can cause serious — even lethal — side effects, such as multiple organ failure, and is not recommended by physicians.[17]

Abortion is sometimes attempted by causing trauma to the abdomen. The degree of force, if severe, can cause serious internal injuries without necessarily succeeding in inducing miscarriage.[18] Both accidental and deliberate abortions of this kind can be subject to criminal liability in many countries. In Burma, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand, there is an ancient tradition of attempting abortion through forceful abdominal massage.[19]

Reported methods of unsafe, self-induced abortion include misuse of misoprostol, and insertion of non-surgical implements such as knitting needles and clothes hangers into the uterus.

Health effects

Early-term surgical abortion is a simple procedure. When performed before the 16th week by competent doctors — or, in some states, nurse practitioners, nurse midwives, and physician assistants — it is safer than childbirth.[20][21]

Abortion methods, like most surgical procedures, carry a small risk of potentially serious complications. These risks include: a perforated uterus,[22][23] perforated bowel[24] or bladder,[citation needed] septic shock,[25] sterility,[26] and death.[27] The risk of complications can increase depending on how far pregnancy has progressed,[28][29] but remains less than complications that may occur from carrying pregnancy to term.[21]

Assessing the risks of induced abortion depends on a number of factors. First, there are relative health risks of induced abortion and pregnancy, which are both affected by wide variation in the quality of health services in different societies and among different socio-economic groups, a lack of uniform definitions of terms, and difficulties in patient follow-up and after-care. The degree of risk is also dependent upon the skill and experience of the practitioner; maternal age, health, and parity;[29] gestational age;[29][28] pre-existing conditions; methods and instruments used; medications used; the skill and experience of those assisting the practitioner; and the quality of recovery and follow-up care.

In the United Kingdom, the number of deaths directly due to legal abortion between the years of 1991 and 1993 was 5, compared to 3 deaths following spontaneous miscarriage and 8 deaths caused by ectopic pregnancy during the same time frame.[30] In the United States, during the year 1999, there were 4 deaths due to legal abortion, 10 due to miscarriage, and 525 due to pregnancy-related reasons.[31][32]

Some practitioners advocate using minimal anaesthesia so the patient can alert them to possible complications. Others recommend general anaesthesia, to prevent patient movement, which might cause a perforation. General anaesthesia carries its own risks, including death, which is why public health officials recommend against its routine use.

Dilation of the cervix carries the risk of cervical tears or perforations, including small tears that might not be apparent and might cause cervical incompetence in future pregnancies. Most practitioners recommend using the smallest possible dilators, and using osmotic rather than mechanical dilators after the first trimester.

Instruments that are placed within the uterus can, on rare occasions, cause perforation[28] or laceration of the uterus, and damage structures surrounding the uterus. Laceration or perforation of the uterus or cervix can, again on rare occasions, lead to more serious complications.

Incomplete emptying of the uterus can cause hemorrhage and infection. Use of ultrasound verification of the location and duration of the pregnancy prior to abortion, with immediate follow-up of patients reporting continuing pregnancy symptoms after the procedure, will virtually eliminate this risk. The sooner a complication is noted and properly treated, the lower the risk of permanent injury or death.

In rare cases, abortion will be unsuccessful and pregnancy will continue. An unsuccessful abortion can result in delivery of a live infant. This, termed a failed abortion, can occur only late in pregnancy. Some doctors have voiced concerns about the ethical and legal ramifications of letting the infant die. As a result, recent investigations have been launched in the United Kingdom by the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health (CEMACH) and the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists, in order to determine how widespread the problem is and what an ethical response in the treatment of the infant might be; a preliminary report from this investigation indicated that at least 50 babies a year are born in the UK following failed abortions after 18 weeks of gestation.[33]

Unsafe abortion methods (e.g. use of certain drugs, herbs, or insertion of non-surgical objects into the uterus) are potentially dangerous, carrying a significantly elevated risk for permanent injury or death, as compared to abortions done by physicians.

Suggested effects

There is controversy over a number of proposed risks and effects of abortion. Evidence, whether in support of or against such claims, might be influenced by the political and religious beliefs of the parties behind it.

Breast cancer

The abortion-breast cancer (ABC) hypothesis (also referred to by supporters as the ABC link) posits a causal relationship between induced abortion and an increased risk of developing breast cancer. In early pregnancy the level of estrogens increases, leading to breast growth in preparation for lactation. The abortion-breast cancer hypothesis proposes that if this process is interrupted with an abortion – before full differentiation in the third trimester – then more relatively vulnerable undifferentiated cells could be left than there were prior to the pregnancy, resulting in a greater potential risk of breast cancer. The hypothesis garnered renewed interest from rat studies conducted in the 1980s,[34][35][36] however, it has not been scientifically verified in humans, and abortion is not considered a breast cancer risk by any major cancer organization.

A large epidemiological study by Mads Melbye et al. in 1997, with data from two national registries in Denmark, reported the correlation to be negligible to non-existent after statistical adjustment.[37] The National Cancer Institute conducted an official workshop with over 100 experts on the issue in February 2003, which concluded with its highest strength rating for the selected evidence that "induced abortion is not associated with an increase in breast cancer risk."[38] In 2004, Beral et al. published a collaborative reanalysis of 53 epidemiological studies and concluded that abortion does "not increase a woman's risk of developing breast cancer."[39]

Critics of these studies argue they are subject to selection bias,[40] that the majority of interview-based studies have indicated a link, and that some are statistically significant.[41] Debate remains as to the reliability of these retrospective studies because of possible response bias. The current scientific consensus has solidified with large prospective cohort studies which find no abortion-breast cancer association,[42][43][44][45] and the ABC issue is seen by some as a part of the current pro-life "women-centered" strategy against abortion.[46] Nevertheless, the subject continues to be one of mostly political but some scientific contention.[47]

Fetal pain

The existence or absence of fetal sensation during abortion is a matter of medical, ethical and public policy interest. Evidence conflicts, with some authorities holding that the fetus is capable of feeling pain from the first trimester,[48][49] and others maintaining that the neuro-anatomical requirements for such experience do not exist until the second or third trimester.[50]

Pain receptors begin to appear in the seventh week of gestation.[49][51] The thalamus, the part of the brain which receives signals from the nervous system and then relays them to the cerebral cortex, starts to form in the fifth week.[52] However, other anatomical structures involved in the nociceptic process are not present until much later in gestation. Links between the thalamus and cerebral cortex form around the 23rd week.[52] There has been suggestion that a fetus cannot feel pain at all, as it requires mental development that only occurs outside the womb.[53]

Researchers have observed changes in heart rates and hormonal levels of newborn infants after circumcision, blood tests, and surgery — effects which were alleviated with the administration of anesthesia.[54] Others suggest that the human experience of pain, being more than just physiological, cannot be measured in such reflexive responses.[55]

Mental health

Post-abortion syndrome (PAS) is a term used to describe a set of mental health characteristics which some researchers claim to have observed in women following an abortion.[56] The psychopathological symptoms attributed to PAS are similar to those of post-traumatic stress disorder, but have also included, "repeated and persistent dreams and nightmares related with the abortion, intense feelings of guilt and the 'need to repair'".[56] Whether this would warrant classification as an independent syndrome is disputed by other researchers.[57] PAS is listed in neither the DSM-IV-TR nor the ICD-10.

Some studies have shown abortion to have neutral or positive effects on the mental well-being of some patients. A 1989 study of teenagers who sought pregnancy tests found that, counting from the beginning of pregnancy until two years later, the level of stress and anxiety of those who had an abortion did not differ from that of those who had not been pregnant or who had carried their pregnancy to term.[58] Another study in 1992 suggested a link between elective abortion and later reports of positive self-esteem; it also noted that adverse emotional reactions to the procedure are most strongly influenced by pre-existing psychological conditions and other negative factors.[59] Abortion, as compared to completion, of an undesired first pregnancy was not found to directly pose the risk of significant depression in a 2005 study.[60]

Other studies have shown a correlation between abortion and negative psychological impact. A 1996 study found that suicide is more common after miscarriage and especially after induced abortion, than in the general population.[61] Additional research in 2002 by David Reardon reported that the risk of clinical depression was higher for women who chose to have an abortion compared to those who opted to carry to term — even if the pregnancy was unwanted.[62] Another study in 2006, which used data gathered over a 25-year period, found an increased occurrence of clinical depression, anxiety, suicidal behavior, and substance abuse among women who had previously had an abortion.[63]

Miscarriage, or spontaneous abortion, is known to present an increased risk of depression.[64] Childbirth can also sometimes result in maternity blues or postpartum depression.

History of abortion

Induced abortion, according to some anthropologists, can be traced to ancient times.[65] There is evidence to suggest that, historically, pregnancies were terminated through a number of methods, including the administration of abortifacient herbs, the use of sharpened implements, the application of abdominal pressure, and other techniques.

The Hippocratic Oath, the chief statement of medical ethics in Ancient Greece, forbade all doctors from helping to procure an abortion by pessary. Nonetheless, Soranus, a second-century Greek physician, suggested in his work Gynaecology that women wishing to abort their pregnancies should engage in violent exercise, energetic jumping, carrying heavy objects, and riding animals. He also prescribed a number of recipes for herbal baths, pessaries, and bloodletting, but advised against the use of sharp instruments to induce miscarriage due to the risk of organ perforation.[66] It is also believed that, in addition to using it as a contraceptive, the ancient Greeks relied upon silphium as an abortifacient. Such folk remedies, however, varied in effectiveness and were not without risk. Tansy and pennyroyal, for example, are two poisonous herbs with serious side effects that have at times been used to terminate pregnancy.

Abortion in the 19th century continued, despite bans in both the United Kingdom and the United States, as the disguised, but nonetheless open, advertisement of services in the Victorian era suggests.[67]

The history of abortion, according to anthropologists, dates back to ancient times. There is evidence to suggest that, historically, pregnancies were terminated through a number of methods, including the administration of abortifacient herbs, the use of sharpened implements, the application of abdominal pressure, and other techniques.

Abortion laws and their enforcement have fluctuated through various eras. Many early laws and church doctrine focused on "quickening," when a fetus began to move on its own, as a way to differentiate when an abortion became impermissible. In the 18th–19th centuries various doctors, clerics, and social reformers successfully pushed for an all-out ban on abortion. During the 20th century abortion has become legal in many Western countries, but it is regularly subjected to legal challenges and restrictions by pro-life groups.[68]

Prehistory to 5th century

The first recorded evidence of induced abortion is from a Chinese document which records abortions performed upon royal concubines in China between the years 500 and 515 B.C.E.[69] According to Chinese folklore, the legendary Emperor Shennong prescribed the use of mercury to induce abortions nearly 5000 years ago.[70]

Abortion, along with infanticide, was well known in the ancient Greco-Roman world. Numerous methods of abortion were used, "the more effective of which were exceedingly dangerous." Several common methods involved either dosing the pregnant woman with a near-fatal amount of poison, in order to induce a miscarriage, introducing poison directly into the uterus, or prodding the uterus with one of a variety of "long needles, hooks, and knives".[71] Unsurprisingly, these methods often led to the death of the woman, as well as the fetus.

There have been archaeological discoveries which would seem to indicate early surgical attempts at the extraction of a fetus; however, such methods are not believed to have been common, given the infrequency with which they are mentioned in ancient medical texts.[72] Many of the methods employed in early and primitive cultures were non-surgical. Physical activities like strenuous labour, climbing, paddling, weightlifting, or diving were a common technique. Others included the use of irritant leaves, fasting, bloodletting, pouring hot water onto the abdomen, and lying on a heated coconut shell.[65] In primitive cultures, techniques developed through observation, adaptation of obstetrical methods, and transculturation.[73]

References in classical literature

Hippocrates, the Greek physician whose famous Oath forbids the use of pessaries to induce abortion, nonetheless writes of having advised a dancer and prostitute who became pregnant to jump up and down, touching her buttocks with her heels at each leap, so as to induce miscarriage.[74] Other writings attributed to him describe instruments, fashioned to dilate the cervix and curette inside of the uterus.[75]

The Hippocratic oath has also been interpreted by medical scholars as prohibiting abortion in a broader sense than by pessary.[76] One such interpretation is by Scribonius Largus, a Roman medical writer said, "Hippocrates, who founded our profession, laid the foundation for our discipline by an oath in which it was proscribed not to give a pregnant woman a kind of medicine that expels the embryo/fetus."[77] Likewise, Soranus wrote in his work on gynecology interpreted the Hippocratic oath as prohibiting any form of drug-induced abortion, and instead advocated the Lacedaemonian leap, or leaping with the heels to the buttocks.

Tertullian, a 2nd and 3rd century Christian theologian, also described surgical implements which were used in a procedure similar to the modern dilation and evacuation. One tool had a "nicely-adjusted flexible frame" used for dilation, an "annular blade" used to curette, and a "blunted or covered hook" used for extraction. The other was a "copper needle or spike." He attributed ownership of such items to Hippocrates, Asclepiades, Erasistratus, Herophilus, and Soranus.[78]

Tertullian's description is prefaced as being used in cases in which abnormal positioning of the fetus in the womb would endanger the life of the pregnant women. Saint Augustine, in Enchiridion, makes passing mention of surgical procedures being performed to remove fetuses which have expired in utero.[79] Aulus Cornelius Celsus, a 1st century Roman encyclopedist, offers an extremely detailed account of a procedure to extract an already dead fetus in his only surviving work, De Medicina.[80]

In Book 9 of Refutation of all Heresies, Saint Hippolytus of Rome, another Christian theologian of the 3rd century, wrote of women tightly binding themselves around the middle so as to "expel what was being conceived."[81]

Soranus, a 2nd century Greek physician, provided some rather detailed suggestions in his work Gynecology. He recommended that women wishing to abort their pregnancies should engage in violent exercise, energetic jumping, carrying heavy objects, and riding animals. Diuretics, emmenagogues, enemas, fasting, and bloodletting, were also prescribed, although Soranus advised against the use of sharp instruments to induce miscarriage due to the risk of organ perforation.[74]

5th century to 16th century

An 8th century Sanskrit text instructs women wishing to induce an abortion to sit over a pot of steam or stewed onions.[82]

The technique of massage abortion, involving the application of pressure to the pregnant abdomen, has been practiced in Southeast Asia for centuries. One of the bas reliefs decorating the temple of Angkor Wat in Cambodia, dated circa 1150, depicts a demon performing such an abortion upon a woman who has been sent to the underworld. This is believed to be the oldest known visual representation of abortion.[19]

Japanese documents show records of induced abortion from as early as the 12th century. It became much more prevalent during the Edo period, especially among the peasant class, who were hit hardest by the recurrent famines and high taxation of the age.[83] Statues of the Boddhisattva Jizo, erected in memory of an abortion, miscarriage, stillbirth, or young childhood death, began appearing at least as early as 1710 at a temple in Yokohama (see religion and abortion).[84]

Physical means of inducing abortion, such as battery, exercise, and tightening the girdle — special bands were sometimes worn in pregnancy to support the belly — were reported among English women during the early modern period.[85]

17th-century to present

Nineteenth century medicine saw advances in the fields of surgery, anaesthesia, and sanitation, in the same era that doctors with the American Medical Association lobbied for bans on abortion in the United States [86] and the British Parliament passed the Offences Against the Person Act.

Various methods of abortion were documented regionally in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. After a rash of unexplained miscarriages in Sheffield, England, were attributed to lead poisoning caused by the metal pipes which fed the city's water supply, a woman confessed to having used diachylon — a lead-containing plaster — as an abortifacient in 1898.[19] Criminal investigation of an abortionist in Calgary, Alberta in 1894 revealed through chemical analysis that the concotion he had supplied to a man seeking an abortifacient contained Spanish fly.[87] Women of Jewish descent in Lower East Side, Manhattan are said to have carried the ancient Indian practice of sitting over a pot of steam into the early 20th century. [82] Dr. Evelyn Fisher wrote of how women living in a mining town in Wales during the 1920s used candles intended for Roman Catholic ceremonies to dilate the cervix in an effort to self-induce abortion.[19] Similarly, the use of candles and other objects, such as glass rods, penholders, curling irons, spoons, sticks, knives, and catheters was reported during the 19th-century in the United States.[88]

A paper published in 1870 on the abortion services to be found in Syracuse, New York, concluded that the method most often practiced there during this time was to flush inside of the uterus with injected water. The article's author, Ely Van de Warkle, claimed this procedure was affordable even to a maid, as a man in town offered it for $10 on an installment plan.[89] Other prices which 19th-century abortionists are reported to have charged were much more steep. In Great Britain, it could cost from 10 to 50 guineas, or 5% of the yearly income of a lower middle class household.[19]

Māori who lived in New Zealand before or at the time of colonisation terminated pregnancies via miscarriage-inducing drugs, ceremonial methods, and girding of the abdomen with a restrictive belt.[90] Another source claims that the Māori people did not practice abortion, for fear of Makutu, but did attempt feticide through the artificial induction of premature labor.[91]

Advertisement of abortion services

Access to abortion continued, despite bans enacted on both sides of the Atlantic Ocean, as the disguised, but nonetheless open, advertisement of abortion services, abortion-inducing devices, and abortifacient medicines in the Victorian era would seem to suggest.[92] Apparent print ads of this nature were found in both the United States,[93] the United Kingdom, [19] and Canada. [94] A British Medical Journal writer who replied to newspaper ads peddling relief to women who were "temporarily indisposed” in 1868 found that over half of them were in fact promoting abortion.[19]

A few alleged examples of surreptitiously-marketed abortifacients include "Farrer's Catholic Pills," "Hardy's Woman's Friend," "Dr. Peter's French Renovating Pills," "Lydia Pinkham's Vegetable Compound",[95] and "Madame Drunette's Lunar Pills." [19] Patent medicines which claimed to treat "female complaints" often contained such ingredients as pennyroyal, tansy, and savin. Abortifacient products were sold under the promise of "restor[ing] female regularity" and "removing from the system every impurity."[95] In the vernacular of such advertising, "irregularity," "obstruction," "menstrual suppression," and "delayed period" were understood to be euphemistic references to the state of pregnancy. As such, some abortifacients were marketed as menstrual regulatives.[88] "Old Dr. Gordon's Pearls of Health," produced by a drug company in Montreal, "cure[d] all suppressions and irregularities" if "used monthly".[96] However, a few ads explicitly warned against the use of their product by women who were expecting, or listed miscarriage as its inevitable side effect. The copy for "Dr. Peter's French Renovating Pills" advised, "...pregnant females should not use them, as they invariably produce a miscarriage...,” and both "Dr. Monroe's French Periodical Pills" and "Dr. Melveau's Portuguese Female Pills" were "sure to produce a miscarriage".[19] F.E. Karn, a man from Toronto, in 1901 cautioned women who thought themselves pregnant not to use the pills he advertised as "Friar's French Female Regulator" because they would "speedily restore menstrual secretions".[96]

Such advertising did not fail to arouse criticisms of quackery and immorality. The safety of many nostrums was suspect and the efficacy of others non-existent. [88] Horace Greeley, in a New York Herald editorial written in 1871, denounced abortion and its promotion as the "infamous and unfortunately common crime—so common that it affords a lucrative support to a regular guild of professional murderers, so safe that its perpetrators advertise their calling in the newspapers".[93] Although the paper in which Greeley wrote accepted such advertisements, others, such as the New York Tribune, refused to print them.[93] Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to obtain a Doctor of Medicine in the United States, also lamented how such ads lead to the contemporary synonymity of "female physician" with "abortionist".[93] The Comstock Law made all abortion-related advertising illegal in the United States (see history of abortion law).

Madame Restell

A well-known example of a Victorian-era abortionist was Madame Restell, or Ann Lohman, who over a forty year period illicitly provided both surgical abortion and abortifacient pills in the northern United States. She began her business in New York during the 1830s, and, by the 1840s, had expanded to include franchises in Boston and Philadelphia.

It is estimated that by 1870 her annual expenditure on advertising alone was $60,000.[19] One ad for Restell's medical services, printed in the New York Sun, promised that she could offer the "strictest confidence on complaints incidental to the female frame" and that her "experience and knowledge in the treatment of cases of female irregularity, [was] such as to require but a few days to effect a perfect cure".[97] Another, addressed to married women, asked the question, "Is it desirable, then, for parents to increase their families, regardless of consequences to themselves, or the well-being of their offspring, when a simple, easy, healthy, and certain remedy is within our control?"[98] Advertisements for the "Female Monthly Regulating Pills" she also sold vowed to resolve "all cases of suppression, irregularity, or stoppage of the menses, however obdurate."[97] Madame Restelle was an object of criticism in both the respectable and penny presses. She was first arrested in 1841, but, it was her final arrest by Anthony Comstock which lead to her suicide on the day of her trial April 1, 1878.[98]

Development of contemporary methods

Although prototypes of the modern curette are referred to in ancient texts, the instrument which is used today was initially designed in France in 1723, but was not applied specifically to a gynecological purpose until 1842.[99] Dilation and curettage has been practiced since the late 19th century.[99]

The 20th century saw improvements in abortion technology, increasing its safety, and reducing its side-effects. Vacuum devices, first described in medical literature in the 1800s, allowed for the development of suction-aspiration abortion.[99] This method was practiced in the Soviet Union, Japan, and China, before being introduced to Britain and the United States in the 1960s.[99] The invention of the Karman cannula, a flexible plastic cannula which replaced earlier metal models in the 1970s, reduced the occurrence of perforation and made suction-aspiration methods possible under local anesthesia.[99] In 1971, Lorraine Rothman and Carol Downer, founding members of the feminist self-help movement, invented the Del-Em, a safe, cheap suction device that made it possible for people with minimal training to perform early abortions called menstrual extraction.[99]

Intact dilation and extraction was developed by Dr. James McMahon in 1983. It resembles a procedure used in the 19th century to save a woman's life in cases of obstructed labor, in which the fetal skull was first punctured with a perforator, then crushed and extracted with a forceps-like instrument, known as a cranioclast.[100][101]

In 1980, researchers at Roussel Uclaf in France developed mifepristone, a chemical compound which works as an abortifacient by blocking hormone action. It was first marketed in France under the trade name Mifegyne in 1988.

Natural abortifacients

Botanical preparations reputed to be abortifacient were common in classical literature and folk medicine. Such folk remedies, however, varied in effectiveness and were not without the risk of adverse effects. Some of the herbs used at times to terminiate pregnancy are poisonous.

Soranus offered a number of recipes for herbal bathes, rubs, and pessaries.[74] In De Materia Medica Libri Quinque, the Greek pharmacologist Dioscorides listed the ingredients of a draught called "abortion wine" — hellebore, squirting cucumber, and scammony — but failed to provide the precise manner in which it was to be prepared.[102] Hellebore, in particular, is known to be abortifacient.[103]

A list of plants which cause abortion was provided in De viribus herbarum, an 11th-century herbal written in the form of a poem, the authorship of which is incorrectly attributed to Aemilius Macer. Among them were rue, Italian catnip, savory, sage, soapwort, cyperus, white and black hellebore, and pennyroyal.[102]

The Greek playwright Aristophanes noted this aspect of pennyroyal much earlier, in 421 B.C.E., through a humorous reference in his comedy, Peace.[104] King's American Dispensatory of 1898 recommended a mixture of brewer's yeast and pennyroyal tea as "a safe and certain abortive." More recently, two women in the United States have died as a result of abortions attempted by pennyroyal, one in 1978 through the consumption of its essential oil and another in 1994 through a tea containing its extract.

Birthwort, an herb used to ease childbirth, was also used to induce abortion. Galen included it in a potion formula in de Antidotis, while Dioscorides said it could be administered by mouth, or in the form of a vaginal pessary also containing pepper and myrrh.[105]

Pliny the Elder cited the refined oil of common rue as a potent abortifacient. Serenus Sammonicus wrote of a concoction which consisted of rue, egg, and dill. Soranus, Dioscorides, Oribasius also detailed this application of the plant. Modern scientific studies have confirmed that rue indeed contains three abortive compounds.[106]

The ancient Greeks relied upon the herb silphium an abortifacient and contraceptive. The plant, as the chief export of Cyrene, was driven to extinction, but it is suggested that it might have possessed the same abortive properties as some of its closest extant relatives in the Apiaceae family. Silphium was so central to the Cyrenian economy that most of its coins were embossed with an image of the plant.

Tansy has been used to terminiate pregnancies since the Middle Ages.[107] It was first documented as an emmenagogue in St. Hildegard of Bingen's De simplicis medicinae.[102]

A variety of juniper, known as savin, was mentioned frequently in European writings.[19] In one case in England, a rector from Essex was said to have procured it for a woman he had impregnated in 1574; in another, a man wishing to remove his girlfriend of like condition recommended to her that black hellebore and savin be boiled together and drunk in milk, or else that chopped madder be boiled in beer. Other substances reputed to have been used by the English include Spanish fly, opium, watercress seed, iron sulphate, and iron chloride. Another mixture, not abortifacient, but rather intended to relieve missed abortion, contained dittany, hyssop, and hot water.[85]

The root of worm fern, tellingly called "prostitute root" in the French, was used of old in France and Germany; it was also recommended by a Greek physician in the 1st century. In German folk medicine, there was also an abortifacient tea, which included marjoram, thyme, parsley, and lavender. Other preparations of unspecificied origin included crushed ants, the saliva of camels, and the tail hairs of black-tailed deer dissolved in the fat of bears.[82]

Social issues

A number of complex issues exist in the debate over abortion. These, like the suggested effects upon health listed above, are a focus of research and a fixture of discussion among members on all sides of the controversy.

Effect upon crime rate

A controversial theory attempts to draw a correlation between the United States' unprecedented nationwide decline of the overall crime rate during the 1990s and the decriminalization of abortion 20 years prior.

The suggestion was brought to widespread attention by a 1999 academic paper, The Impact of Legalized Abortion on Crime, authored by the economists Steven D. Levitt and John Donohue. They attributed the drop in crime to a reduction in individuals said to have a higher statistical probability of committing crimes: unwanted children, especially those born to mothers who are African-American, impoverished, adolescent, uneducated, and single. The change coincided with what would have been the adolescence, or peak years of potential criminality, of those who had not been born as a result of Roe v. Wade and similar cases. Donohue and Levitt's study also noted that states which legalized abortion before the rest of the nation experienced the lowering crime rate pattern earlier, and those with higher abortion rates had more pronounced reductions.[108]

Fellow economists Christopher Foote and Christopher Goetz criticized the methodology in the Donohue-Levitt study, noting a lack of accommodation for statewide yearly variations such as cocaine use, and recalculating based on incidence of crime per capita; they found no statistically significant results.[109] Levitt and Donohue responded to this by presenting an adjusted data set which took into account these concerns and reported that the data maintained the statistical significance of their initial paper.[110]

Such research has been criticized by some as being utilitarian, discriminatory as to race and socioeconomic class, and as promoting eugenics as a solution to crime.[111][112] Levitt states in his book, Freakonomics, that they are neither promoting nor negating any course of action — merely reporting data as economists.

Sex-selective abortion

The advent of both sonography and amniocentesis has allowed parents to determine sex before birth. This has led to the occurrence of sex-selective abortion or the targeted termination of a fetus based upon its sex.

It is suggested that sex-selective abortion might be partially responsible for the noticeable disparities between the birth rates of male and female children in some places. The preference for male children is reported in many areas of Asia, and abortion used to limit female births has been reported in Mainland China, Taiwan, South Korea, and India.[113]

In India, the economic role of men, the costs associated with dowries, and a Hindu tradition which dictates that funeral rites must be performed by a male relative have led to a cultural preference for sons.[114] The widespread availability of diagnostic testing, during the 1970s and '80s, led to advertisements for services which read, "Invest 500 rupees [for a sex test] now, save 50,000 rupees [for a dowry] later."[115] In 1991, the male-to-female sex ratio in India was skewed from its biological norm of 105 to 100, to an average of 108 to 100.[116] Researchers have asserted that between 1985 and 2005 as many as 10 million female fetuses may have been selectively aborted.[117] The Indian government passed an official ban of pre-natal sex screening in 1994 and moved to pass a complete ban of sex-selective abortion in 2002.[118]

In the People's Republic of China, there is also a historic son preference. The implementation of the one-child policy in 1979, in response to population concerns, led to an increased disparity in the sex ratio as parents attempted to circumvent the law through sex-selective abortion or the abandonment of unwanted daughters.[119] Sex-selective abortion might be an influence on the shift from the baseline male-to-female birth rate to an elevated national rate of 117:100 reported in 2002. The trend was more pronounced in rural regions: as high as 130:100 in Guangdong and 135:100 in Hainan.[120] A ban upon the practice of sex-selective abortion was enacted in 2003.[121]

Unsafe abortion

Where and when access to safe abortion has been barred, due to explicit sanctions or general unavailability, women seeking to terminate their pregnancies have sometimes resorted to unsafe methods.

"Back-alley abortion" is a slang term for any abortion not practiced under generally accepted standards of sanitation and professionalism. The World Health Organization defines an unsafe abortion as being, "a procedure...carried out by persons lacking the necessary skills or in an environment that does not conform to minimal medical standards, or both."[9] This can include a person without medical training, a professional health provider operating in sub-standard conditions, or the woman herself.

Unsafe abortion remains a public health concern today due to the higher incidence and severity of its associated complications, such as incomplete abortion, sepsis, hemorrhage, and damage to internal organs. WHO estimates that 19 million unsafe abortions occur around the world annually and that 68,000 of these result in the woman's death.[9] Complications of unsafe abortion are said to account, globally, for approximately 13% of all maternal mortalities, with regional estimates including 12% in Asia, 25% in Latin America, and 13% in sub-Saharan Africa.[122] Health education, access to family planning, and improvements in health care during and after abortion have been proposed to address this phenomenon.[123]

Abortion debate

Over the course of the history of abortion, induced abortion has been the source of considerable debate, controversy, and activism. An individual's position on the complex ethical, moral, philosophical, biological, and legal issues is often related to his or her value system. Opinions of abortion may be best described as being a combination of beliefs on its morality, and beliefs on the responsibility, ethical scope, and proper extent of governmental authorities in public policy. Religious ethics also has an influence upon both personal opinion and the greater debate over abortion (see religion and abortion).

Abortion debates, especially pertaining to abortion laws, are often spearheaded by advocacy groups belonging to one of two camps. In the United States, most often those in favor of legal prohibition of abortion describe themselves as pro-life while those against legal restrictions on abortion describe themselves as pro-choice. Both are used to indicate the central principles in arguments for and against abortion: "Is the fetus a human being with a fundamental right to life?" for pro-life advocates, and, for those who are pro-choice, "Does a woman have the right to choose whether or not to continue a pregnancy?"

In both public and private debate, arguments presented in favor of or against abortion focus on either the moral permissibility of an induced abortion, or justification of laws permitting or restricting abortion. Arguments on morality and legality tend to collide and combine, complicating the issue at hand.

Debate also focuses on whether the pregnant woman should have to notify and/or have the consent of others in distinct cases: a minor, her parents; a legally-married or common-law wife, her husband; or a pregnant woman, the biological father. In a 2003 Gallup poll in the United States, 72% of respondents were in favor of spousal notification, with 26% opposed; of those polled, 79% of males and 67% of females responded in favor.[124]

Public opinion

A number of opinion polls around the world have explored public opinion regarding the issue of abortion. Results have varied from poll to poll, country to country, and region to region, while varying with regard to different aspects of the issue.

A May 2005 survey examined attitudes toward abortion in 10 European countries, asking polltakers whether they agreed with the statement, "If a woman doesn't want children, she should be allowed to have an abortion." The highest level of approval was 81% in the Czech Republic and the highest level of disapproval was 48% in Poland.[125]

In North America, a December 2001 poll surveyed Canadian opinion on abortion, asking Canadians in what circumstances they believe abortion should be permitted; 32% responded that they believe abortion should be legal in all circumstances, 52% that it should be legal in certain circumstances, and 14% that it should be legal in no circumstances. A similar poll in January 2006 surveyed people in the United States about U.S. opinion on abortion; 33% said that abortion should be "permitted only in cases such as rape, incest or to save the woman's life," 27% said that abortion should be "permitted in all cases," 15% that it should be "permitted, but subject to greater restrictions than it is now," 17% said that it should "only be permitted to save the woman's life," and 5% said that it should "never" be permitted.[126] A November 2005 poll in Mexico found that 73.4% think abortion should not be legalized while 11.2% think it should.[127]

Of attitudes in South and Central America, a December 2003 survey found that 30% of Argentines thought that abortion in Argentina should be allowed "regardless of situation," 47% that it should be allowed "under some circumstances," and 23% that it should not be allowed "regardless of situation".[128] A poll regarding the abortion law in Brazil found that 63% of Brazilians believe that it "should not be modified," 17% that it should be expanded "to allow abortion in other cases," 11% that abortion should be "decriminalized," and 9% were "unsure".[129] A July 2005 poll in Colombia found that 65.6% said they thought that abortion should remain illegal, 26.9% that it should be made legal, and 7.5% that they were unsure.[130]

Abortion law

Before the scientific discovery that human development begins at fertilization, English common law allowed abortions to be performed before "quickening," the earliest perception of fetal movement by a woman during pregnancy, until both pre- and post-quickening abortions were criminalized by Lord Ellenborough's Act in 1803.[131] In 1861, the British Parliament passed the Offences Against the Person Act, which continued to outlaw abortion and served as a model for similar prohibitions in some other nations. [132] The Soviet Union, with legislation in 1920, and Iceland, with legislation in 1935, were two of the first countries to generally allow abortion. The second half of the 20th century saw the liberalization of abortion laws in other countries. The Abortion Act 1967 allowed abortion for limited reasons in the United Kingdom. In the 1973 case, Roe v. Wade, the United States Supreme Court struck down state laws banning abortion, ruling that such laws violated an implied right to privacy in the United States Constitution. The Supreme Court of Canada, similarly, in the case of R. v. Morgentaler, discarded its criminal code regarding abortion in 1988, after ruling that such restrictions violated the security of person guaranteed to women under the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Canada later struck down provincial regulations of abortion in the case of R. v. Morgentaler (1993). By contrast, abortion in Ireland was affected by the addition of an amendment to the Irish Constitution in 1983 by popular referendum, recognizing "the right to life of the unborn."

Current laws pertaining to abortion are diverse. Religious, moral, and cultural sensibilities continue to influence abortion laws throughout the world. The right to life, the right to liberty, and the right to security of person are major issues of human rights that are sometimes used as justification for the existence or absence of laws controlling abortion. Many countries in which abortion is legal require that certain criteria be met in order for an abortion to be obtained, often, but not always, using a trimester-based system to regulate the window of legality:

- In the United States, some states impose a 24-hour waiting period before the procedure, prescribe the distribution of information on fetal development, or require that parents be contacted if their minor daughter requests an abortion.

- In the United Kingdom, as in some other countries, two doctors must first certify that an abortion is medically or socially warranted before it can be performed. However, since UK law stipulates that a woman seeking an abortion should never be barred from seeking another doctor's referral, and since some doctors believe that abortion is in all cases medically or socially warranted, in practice women are never fully barred from obtaining an abortion.[133]

Other countries, in which abortion is normally illegal, will allow one to be performed in the case of rape, incest, or danger to the pregnant woman's life or health. A few nations ban abortion entirely: Chile, El Salvador, Malta, and Nicaragua, although in 2006 the Chilean government began the free distribution of emergency contraception.[134][135] In Bangladesh, abortion is illegal, but the government has long supported a network of "menstrual regulation clinics," where menstrual extraction (manual vacuum aspiration) can be performed as menstrual hygiene.[136]

The history of abortion law dates back to ancient times and has impacted men and women in a variety of ways in different times and places. Historically, it is unclear how often the ethics of abortion (induced abortion) was discussed, but under Christian influence the West generally frowned on abortion. In the 18th century, English and American common law allowed abortion if performed before "quickening." By the late 19th century many nations had passed laws that banned abortion. In the later half of the 20th century some nations began to legalize abortion. This controversial subject has sparked heated debate and in some cases even violence against abortion providers.

Prehistory to 5th century

Some previous civilizations are thought to have tolerated even late-term abortions. There were also opposing voices, most notably Hippocrates of Cos and the Roman Emperor Augustus. Aristotle wrote that, "[T]he line between lawful and unlawful abortion will be marked by the fact of having sensation and being alive."[137] In contrast to their pagan environment, Christians generally shunned abortion, drawing upon the Bible and early Christian writings such as the Didache (circa 100 C.E.), which says: "... thou shalt not murder a child by abortion nor kill the infant already born."[138] Saint Augustine believed that abortion of a fetus animatus, a fetus with human limbs and shape, was murder. However, his beliefs on earlier-stage abortion were similar to Aristotle's, [139] though he could neither deny nor affirm whether such unformed fetuses would be resurrected as full people at the time of the second coming.[140]

- "The fetus in the womb is . . . an object of God's care," and, "We say that women who induce abortions are murderers, and will have to give account of it to God." (Athenagoras, late 2nd century)

- "In our case, murder being once for all forbidden, we may not destroy even the fetus in the womb." (Tertullian, late 2nd century)

- "There are women who . . . [are] committing infanticide before they give birth to the infant." (Minucious Felix, early 3rd century)

- "Those . . . who give drugs causing abortion are [deliberate murderers] themselves, as well as those receiving the poison which kills the fetus." (Basil, 4th century)

- "They drink potions to ensure sterility and are guilty of murdering a human being not yet conceived. Some, when they learn that they are with child through sin, practice abortion by the use of drugs. Frequently they die themselves and are brought before the rulers of the lower world guilty of three crimes: suicide, adultery against Christ, and murder of an unborn child." (Jerome, 4th century)

- "But who is not rather disposed to think that unformed fetuses perish like seeds which have not fructified?" (Saint Augustine, Enchiridion, ch. 85 [140])

- "And therefore the following question may be very carefully inquired into and discussed by learned men, though I do not know whether it is in man's power to resolve it: At what time the infant begins to live in the womb: whether life exists in a latent form before it manifests itself in the motions of the living being. To deny that the young who are cut out limb by limb from the womb, lest if they were left there dead the mother should die too, have never been alive, seems too audacious." (Saint Augustine, Enchiridion ch. 86[140])

5th century to 16 century

- 1140 - The monk John Gratian completed the Concordia discordantium canonum (Harmony of Contradictory Laws) which became the first authoritative collection of Canon law accepted by the Church. In accordance with ancient scholars, it concluded the moral crime of early abortion was not equivalent to that of homicide.

- c. 1200 - Pope Innocent III wrote that when "quickening" occurred, abortion was homicide. Before that, abortion was considered a less serious sin.

- 1250 - According to ancient English common law, abortion after fetal movement or "quickening" was punishable as homicide, and abortion was also punishable "if the foetus is already formed" but not yet quickened, according to Henry Bracton.[141]

- c. 1395 - The Lollards, an English proto-Protestant group, denounce the practice of abortion in The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards.

- 1487 - Malleus Maleficarum (The Hammer of Witches), a witch-hunting manual, is published in Germany. It accuses midwives who perform abortions of committing witchcraft.[142]

- 1588 - Pope Sixtus V aligned Church policy with St. Thomas Aquinas' belief that contraception and abortion were crimes against nature and sins against marriage.

- 1591 - Pope Gregory XIV decreed that prior to 116 days (~17 weeks), Church penalties would not be any stricter than local penalties, which varied from country to country.

17th century to 19th century

- 1765 - Post-quickening abortion was no longer considered homicide in England, but William Blackstone called it "a very heinous misdemeanor".[143]

- 1803 - England enacts Lord Ellenborough's Act, making abortion after quickening a capital crime, and providing lesser penalties for the felony of abortion before quickening.[144]

- 1842 - The Shogunate in Japan bans induced abortion in Edo. The law does not affect the rest of the country.[83]

- 1861 - The British Parliament passes the Offences Against The Person Act which outlaws abortion.

- 1869 - Pope Pius IX declared that abortion under any circumstance was gravely immoral (mortal sin), and, that anyone who participated in an abortion in any material way had by virtue of that act excommunicated themselves from the Church. In the same year, the Parliament of Canada unifies criminal law in all provinces, banning abortion.

- 1873 - The passage of the Comstock Law in the United States makes it a crime to sell, distribute, or own abortion-related products and services, or to publish information on how to obtain them (see advertisement of abortion services).

- 1820–1900 - Through the efforts primarily of physicians in the American Medical Association and legislators, most abortions in the U.S. were outlawed.

- 1850–1920 - During the fight for women's suffrage in the U.S., some notable first-wave feminists, such as Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Mary Wollstonecraft, opposed abortion.[145]

1920s to 1960s

- 1920 - Lenin legalized all abortions in the Soviet Union.

- 1935 - Nazi Germany amended its eugenics law, Law for the Prevention of Hereditarily Diseased Offspring, to promote abortion for women who have congenital and genetic disorders, or whose unborn fetuses have such hereditary disorders.[146]

- 1935 - Iceland became the first Western country to legalize therapeutic abortion under limited circumstances.

- 1936 - Joseph Stalin reversed Lenin's legalization of abortion in the Soviet Union to increase population growth.

- 1936 - Heinrich Himmler, Chief of the SS, creates the "Reich Central Office for the Combating of Homosexuality and Abortion." Himmler hoped to reverse a decline in the "Aryan" birthrate which he attributed to homosexuality among men and abortion among German women.[147]

- 1938 - In Britain, Dr. Aleck Bourne aborted the pregnancy of a young girl who had been raped by soldiers. Bourne was acquitted after turning himself into authorities. The legal precedent of allowing abortion in order to avoid mental or physical damage was picked up by the Commonwealth of Nations.

- 1938 - Abortion legalized on a limited basis in Sweden.

- 1948 - The Eugenic Protection Act in Japan expanded the circumstances in which abortion is allowed.[148]

- 1967 - The Abortion Act legalized abortion in the United Kingdom except in Northern Ireland. In the U.S., California and Colorado became the first U.S. states to legalize abortion.

- 1969 - Canada began to allow abortion for selective reasons.

- 1969 - The ruling in the Victorian case of R v Davidson defined for the first time which abortions are lawful in Australia.

- 1969–1973 - The Jane Collective operated in Chicago, offering illegal abortions.

1970s to present

- 1970 - New York legalized abortion, to much opposition, primarily from African-American activists.

- 1973 - The U.S. Supreme Court, in Roe v. Wade, declared all the individual state bans on abortion during the first and second trimesters to be unconstitutional. The Court also legalized abortion in the third trimester when a woman's doctor believes the abortion is necessary for her physical or mental health.

- 1973–1980 - France (1975), West Germany (1976), New Zealand (1977), Italy (1978), and the Netherlands (1980) legalized abortion in limited circumstances.

- 1979 - The People's Republic of China enacted a one-child policy, leaving some women to either undergo an abortion or violate the policy and face economic penalties in some circumstances.

- 1983 - Ireland, by popular referendum, added an amendment to its Constitution recognizing "the right to life of the unborn." Abortions is still illegal in Ireland, except for urgent medical purposes to save a woman's life.

- 1988 - France legalized the "abortion pill" mifepristone (RU-486).

- 1990 - The Abortion Act in the UK was amended so that abortion is legal only up to 24 weeks, rather than 28, except in unusual cases.

- 1993 - Poland banned abortion, except in cases of rape, incest, severe congenital disorders, or threat to the life of the pregnant woman.

- 1996 - Republic of South Africa the 'Choice on Termination of Pregnancy Act 92 of 1996' comes into effect (Repealing the 'Abortion and Sterilization Act 2 of 1975' which only allowed abortions in certain circumstances) lawfully permitting abortions by choice. Act is often challenged in Court.

- 1998 - Republic of South Africa the abortion question is finally answered when the Transvaal Provincial Division in "'Christian Lawyers Association and Others v Minister of Health and Others (50 BMLR 241)" where the Court held that abortions are legal in terms of the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996.

- 1999 - In the United States, Congress passed a ban on intact dilation and extraction, which President Bill Clinton vetoed.

- 2000 - Mifepristone (RU-486) approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

- 2003 - The U.S. enacted the Partial-Birth Abortion Ban Act and President George W. Bush signed it into law. After the law was challenged in three appeals courts, the U.S. Supreme Court held that it was constitutional because, unlike the earlier Nebraska state law, it was not vague or overly broad. The court also held that banning the procedure did not constitute an "undue burden," even without a health exception. Gonzales v. Carhart

- 2007 The Parliament of Portugal voted to legalize abortion during the first ten weeks of pregnancy. This followed a referendum that, while revealing that a majority of Portuguese voters favored legalization of early-stage abortions, failed due to low voter turnout. President Cavaco Silva must sign the measure before it will go into effect. [4]

Notes

- ↑ Roche, Natalie E. (2004). Therapeutic Abortion. Retrieved 2006-03-08.

- ↑ Henshaw, Stanley K., Singh, Susheela, & Haas, Taylor. (1999). The Incidence of Abortion Worldwide. International Family Planning Perspectives, 25 (Supplement), 30 – 8. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- ↑ Strauss, L.T., Gamble, S.B., Parker, W.Y, Cook, D.A., Zane, S.B., & Hamdan, S. (November 24, 2006). Abortion Surveillance - United States, 2003. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 55 (11), 1-32. Retrieved May 10, 2007.

- ↑ Finer, Lawrence B. & Henshaw, Stanley K. (2003). Abortion Incidence and Services in the United States in 2000. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 35 (1). Retrieved 2006-05-10.

- ↑ Government Statistical Service for the Department of Health. (July 4, 2006). Abortion statistics, England and Wales: 2005. Retrieved May 10, 2007.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bankole, Akinrinola, Singh, Susheela, & Haas, Taylor. (1998). Reasons Why Women Have Induced Abortions: Evidence from 27 Countries. International Family Planning Perspectives, 24 (3), 117-127 & 152. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Finer, Lawrence B., Frohwirth, Lori F., Dauphinee, Lindsay A., Singh, Shusheela, & Moore, Ann M. (2005). Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantative and qualitative perspectives. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 37 (3), 110-8. Retrieved 2006-01-18.

- ↑ Jones, Rachel K., Darroch, Jacqueline E., Henshaw, Stanley K. (2002). Contraceptive Use Among U.S. Women Having Abortions in 2000-2001. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health, 34 (6). Retrieved June 15, 2006.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 World Health Organization. (2004). Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2000. Retrieved 2006-01-12.

- ↑ "Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility: Recurrent Pregnancy Loss (Recurrent Miscarriage)." (n.d.) Retrieved 2006-01-18 from Washington University School of Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology web site.

- ↑ Q&A: Miscarriage. (August 6 , 2002). BBC News. Retrieved January 10, 2007. Lennart Nilsson. (1990) A Child is Born.

- ↑ Healthwise. Manual and vacuum aspiration for abortion. (2004). WebMD. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ World Health Organization. (2003). Managing complications in pregnancy and childbirth: a guide for midwives and doctors. Retrieved 2006-08-19.

- ↑ -Vause S, Sands J, Johnston TA, Russell S, Rimmer S. (2002). PMID 12521492 Could some fetocides be avoided by more prompt referral after diagnosis of fetal abnormality? J Obstet Gynaecol. 2002 May;22(3):243-5. Retrieved 2006-03-17.

-Dommergues M, Cahen F, Garel M, Mahieu-Caputo D, Dumez Y. (2003). PMID 12576743 Feticide during second- and third-trimester termination of pregnancy: opinions of health care professionals. Fetal Diagn Ther. 2003 Mar-Apr;18(2):91-7. Retrieved 2006-03-17.

-Bhide A, Sairam S, Hollis B, Thilaganathan B. (2002). PMID 12230443 Comparison of feticide carried out by cordocentesis versus cardiac puncture. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2002 Sep;20(3):230-2. Retrieved 2006-03-17.

-Senat MV, Fischer C, Bernard JP, Ville Y. (2003). PMID 12628271 The use of lidocaine for fetocide in late termination of pregnancy. BJOG. 2003 Mar;110(3):296-300. Retrieved 2006-03-17.

- MV, Fischer C, Ville Y. (2002). PMID 12001185 Funipuncture for fetocide in late termination of pregnancy. Prenat Diagn. 2002 May;22(5):354-6. Retrieved 2006-03-17. - ↑ Spitz, I.M. et al (1998). Early pregnancy termination with mifepristone and misoprostol in the United States. New England Journal of Medicine 338 (18). PMID 9562577.

- ↑ Riddle, John M. (1997). Eve's Herbs: A History of Contraception and Abortion in the West. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Ciganda, C., & Laborde, A. (2003). Herbal infusions used for induced abortion. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol, 41(3), 235-9. Retrieved 2006-01-25.

- ↑ Education for Choice. (2005-05-06). Unsafe abortion. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 Potts, Malcolm, & Campbell, Martha. (2002). History of contraception. Gynecology and Obstetrics, vol. 6, chp. 8. Retrieved 2005-01-25. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "potts" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Cates W., Jr, & Tietze C. (1978). Standardized mortality rates associated with legal abortion: United States, 1972-1975 Electronic version. Family Planning Perspectives, 10 (2), 109-12. Retrieved 2006-01-28.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Grimes, D.A. (1994). The morbidity and mortality of pregnancy: still risky business. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 170 (5 Pt 2), 1489-94. Retrieved December 21, 2006.

- ↑ Legarth, J., Peen, U.B., & Michelsen, J.W. (1991). Mifepristone or vacuum aspiration in termination of early pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, 41 (2), 91-6. Retrieved December 21, 2006.

- ↑ Mittal, S., & Misra, S.L. (1985). Uterine perforation following medical termination of pregnancy by vacuum aspiration. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 23 (1), 45-50. Retrieved December 21, 2006.

- ↑ WHO Health Organization. Medical Methods for termination of pregnancy. WHO Technical Report Series 871, 1997

- ↑ Dzhavakhadze, M.V., & Daraselia, M.I. (2005). Mortality case analyses of obstetric-gynecologic sepsis. Georgian Medical News, 127, 26-9. Retrieved December 21, 2006.

- ↑ Tzonou, A., Hsieh, C.C., Trichopoulos, D., Aravandinos, D., Kalandidi, A., Margaris, D., Goldman, M., et al. (1993) Induced abortions, miscarriages, and tobacco smoking as risk factors for secondary infertility. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 47 (1), 36-9. Retrieved December 21, 2006.

- ↑ Lanska, M.J., Lanska, D., & Rimm, A.A. (1983). Mortality from abortion and childbirth. Journal of the American Medical Association, 250(3), 361-2. Retrieved December 21, 2006.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Pauli, E., Haller, U., Zimmermann, R. (2005). Morbidity of dilatation and evacuation in the second trimester: an analysis. Gynakol Geburtshilfliche Rundsch, 45 (2), 107-15. Retrieved December 26, 2006.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Bartley, J., Tong, S., Everington, D.,& Baird, D.T. (2000). Parity is a major determinant of success rate in medical abortion: a retrospective analysis of 3161 consecutive cases.... Contraception, 62(6), 297-303. Retrieved December 26, 2006.

- ↑ Department of Health. (1998). Why Mothers Die: Report on Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths in the United Kingdom 1994 – 1996. London: The Stationery Office. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- ↑ Elam-Evans, Laurie. D., Strauss, Lilo T., Herndon, Joy, Parker, Wilda Y., Bowens, Sonya V., Zane, Suzanne, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2003-11-23). Abortion Surveillance - United States, 2000. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2003-02-20). Fact Sheet: Pregnancy-Related Mortality Surveillance - United States, 1991-1999. Retrieved 2006-04-02.

- ↑ Rogers, Lois. (2005-11-27). "Fifty babies a year are alive after abortion." The Sunday Times. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- ↑ Russo J., Russo I.H. (1980) PubMed Susceptibility of the mammary gland to carcinogenesis. II. Pregnancy interruption as a risk factor in tumor incidence. Am J Pathol. 1980 Aug;100(2):497-512.

- ↑ Russo J. et al. (1982) PubMed Differentiation of the mammary gland and susceptibility to carcinogenesis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1982;2(1):5-73.

- ↑ Russo J., Russo I.H. (1987) PubMed Biological and molecular bases of mammary carcinogenesis. Lab Invest. 1987 Aug;57(2):112-37.

- ↑ Melbye M, Wohlfahrt J, Olsen J, Frisch M, Westergaard T, Helweg-Larsen K, Andersen P (1997). Induced abortion and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med 336 (2): 81-5.

- ↑ National Cancer Institute. (2003-03-04). Summary Report: Early Reproductive Events and Breast Cancer Workshop. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- ↑ Beral V, Bull D, Doll R, Peto R, Reeves G (2004). Breast cancer and abortion: collaborative reanalysis of data from 53 epidemiological studies, including 83?000 women with breast cancer from 16 countries. Lancet 363 (9414): 1007-16.

- ↑ bcpinstitute.org – FACT SHEET: Abortion and Breast Cancer: re: "collaborative reanalysis of data" published in Lancet 3/25/04 (1)

- ↑ Etters.net – American abortion-breast cancer studies

- ↑ American Cancer Society. (2006-10-03) Cancer.org – What Are the Risk Factors for Breast Cancer? Retrieved 2006-03-30.

- ↑ Reeves G, Kan S, Key T, Tjønneland A, Olsen A, Overvad K, Peeters P, Clavel-Chapelon F, Paoletti X, Berrino F, Krogh V, Palli D, Tumino R, Panico S, Vineis P, Gonzalez C, Ardanaz E, Martinez C, Amiano P, Quiros J, Tormo M, Khaw K, Trichopoulou A, Psaltopoulou T, Kalapothaki V, Nagel G, Chang-Claude J, Boeing H, Lahmann P, Wirfält E, Kaaks R, Riboli E (2006). Breast cancer risk in relation to abortion: Results from the EPIC study. Int. J. Cancer 119 (7): 1741-5.

- ↑ Rosenblatt K, Gao D, Ray R, Rowland M, Nelson Z, Wernli K, Li W, Thomas D (2006). Induced abortions and the risk of all cancers combined and site-specific cancers in Shanghai. Cancer Causes Control 17 (10): 1275-80.

- ↑ Karin B. Michels, ScD, PhD; Fei Xue, MD; Graham A. Colditz, MD, DrPH; Walter C. Willett, MD, DrPH. "Induced and Spontaneous Abortion and Incidence of Breast Cancer Among Young Women." Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:814-820.

- ↑ Arthur, Joyce. (2002) ProChoiceActionNetwork-Canada.org – Abortion and Breast Cancer — A Forged Link

- ↑ Jasen P (2005). Breast cancer and the politics of abortion in the United States. Med Hist 49 (4): 423-44.

- ↑ Schmidt, Dr. Richard T. F., et al. (1984-02-13). Open Letter to President Reagan. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-11-18.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Robinson, B.A. (2006). Can a fetus feel pain?. Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance. Retrieved December 14, 2005.

- ↑ BBC News Article (2005). "Foetuses 'no pain up to 29 weeks'." Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- ↑ Myers, Laura B. (2003). Fetal Surgery: The Anathesia Perspective. Retrieved March 14, 2007.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Parliamentary Office of Science and Technology. (1997). Fetal Awareness. Retrieved 2006-01-11.

- ↑ BBC News Article (2006). "Foetuses 'cannot experience pain'." Retrieved 2006-07-18.

- ↑ Anand, K., Phil, D., & Hickey, P.R. (1987). Pain and its effects on the human neonate and fetus. New England Journal of Medicine, 316 (21), 1321-9. Retrieved 2006-01-11 from The Circumcision Reference Library.

- ↑ Lee, Susan J., Ralston, Henry J. Peter, Drey, Eleanor A., Partridge, John Colin, & Rosen, Mark A. (2005). Fetal Pain: A Systematic Multidisciplinary Review of the Evidence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 294 (8), 947-954. Retrieved November 10, 2006.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 Gomez, Lavin C., & Zapata, Garcia R. (2005). - "Diagnostic categorization of post-abortion syndrome". Actas Esp Psiquiatr, 33 (4), 267-72. Retrieved Setepmber 8, 2006.

- ↑ Stotland, N.L. (1992). The myth of the abortion trauma syndrome. Journal of the American Medical Association, 268 (15), 2078-9. Retrieved December 7, 2006.

- ↑ Zabin, L.S., Hirsch, M.B., Emerson, M.R. (1989). When urban adolescents choose abortion: effects on education, psychological status and subsequent pregnancy. Family Planning Perspectives, 21 (6), 248-55. Retrieved September 8, 2006.

- ↑ Russo, N. F., & Zierk, K.L. (1992). Abortion, childbearing, and women. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 23(4), 269-280. Retrieved September 8, 2006.

- ↑ Schmiege, S. & Russo, N.F. (2005). Depression and unwanted first pregnancy: longitudinal cohort study Electronic version . British Medical Journal, 331 (7528), 1303. Retrieved 2006-01-11.