Mercury (element)

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| General | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name, Symbol, Number | mercury, Hg, 80 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chemical series | transition metals | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group, Period, Block | 12, 6, d | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic mass | 200.59(2) g/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Xe] 4f14 5d10 6sÂČ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 18, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase | liquid | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | (liquid) 13.534 g/cmÂł | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 234.32 K (-38.83 °C, -37.89 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 629.88 K (356.73 °C, 674.11 °F) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 1750 K, 172.00 MPa | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 2.29 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 59.11 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Heat capacity | (25 °C) 27.983 J/(mol·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | rhombohedral | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | 2, 1 (mildly basic oxide) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | 2.00 (Pauling scale) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies | 1st: 1007.1 kJ/mol | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 2nd: 1810 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 3rd: 3300 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | 150 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius (calc.) | 171 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 149 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 155 pm | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Miscellaneous | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | diamagnetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | (25 °C) 961 nΩ·m | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | (300 K) 8.30 W/(m·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | (25 °C) 60.4 ”m/(m·K) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound | (liquid, 20 °C) 1451.4 m/s | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS registry number | 7439-97-6 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Notable isotopes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mercury, also called quicksilver (chemical symbol Hg, atomic number 80), is a chemical element and transition metal that at room temperature and pressure is a heavy, silvery liquid.

Natural deposits of mercury-bearing minerals, usually in the form of cinnabar, a sulfide of mercury, have been found throughout the world. Elemental mercury is used in the manufacture of certain chemicals, paints, batteries, electronic items, and fluorescent lamps. It is the major constituent of traditional dental amalgams. It is used in some thermometers, barometers, and other types of scientific apparatus. The organomercury compound Thiomersal (commonly called Thimerosol) is a widely used antibacterial and antifungal agent. Cinnabar ore is still used in some cultures for medical treatments.

Mercury and most of its compounds are highly toxic and need to be handled with extreme care. To prevent inhalation and skin contact, they are stored in sealed containers. The most poisonous compounds of mercury are its soluble salts (such as mercuric chloride) and organic compounds (such as methylmercury).

The organomercury compound Thimerosol has been widely used as an antibacterial agent in multiple-dose vaccine treatments, which entails injecting the patient with Thimerosol along with the vaccine. Concern that Thimerosol in vaccines used on infants may contribute to autism has led in the US and a few other countries to replacement of multiple-dose treatments with mercury-free single dose treatments, even though the causation from Thimerosol to autism is unproven. Concern about possible health damage from mercury in dental fillings has led the development and use of mercury-free amalgams.

In its various forms, mercury circulates widely through the air and water and accumulates as methylmercury up the food chain of fish in oceans and lakes giving the top-level predator fish like tuna such high levels that health advisories warn against eating such fish too frequently. Primary sources of environmental mercury include the manufacture and use of batteries, fungicides, and paints; the burning of wastes (municipal, hazardous, and medical); and the burning of fossil fuels (coal and natural gas). In Western Europe and the US, environmental mercury levels peaked in the 1950s and 1960s and have since been reduced.

Etymology

The modern chemical symbol for mercury is Hg. It comes from hydrargyrum, a Latinized form of the Greek word `΄ΎÏαÏÎłÏ ÏÎżÏ (hydrargyros), which is a compound word meaning "water" and "silver"âbecause it is liquid, like water, and yet has a silvery metallic sheen. The element was named after the Roman god Mercury, known for speed and mobility. It is associated with the planet Mercury. The astrological symbol for the planet is also one of the alchemical symbols for the metal (left). Mercury is the only metal for which the alchemical planetary name became the common name.

Occurrence

Mercury is an extremely rare element in the earth's crust, having an average crustal abundance by mass of only 0.08 parts per million. However, because it does not blend geochemically with those elements that comprise the majority of the crustal mass, mercury ores can be extraordinarily concentrated considering the element's abundance in ordinary rock. The richest mercury ores contain up to 2.5 percent mercury by mass, and even the leanest concentrated deposits are at least 0.1 percent mercury (12,000 times average crustal abundance).

It is found either as a native metal (rare) or in cinnabar, corderoite, livingstonite and other minerals, with cinnabar (HgS) being the most common ore. Mercury ores usually occur in very young orogenic belts where rocks of high density are forced to the crust of the Earth, often in hot springs or other volcanic regions.

Over 100,000 tons of mercury were mined from the region of Huancavelica, Peru, over the course of three centuries following the discovery of deposits there in 1563. Mercury from Huancavelica was crucial in the production of silver in colonial Spanish America. Many former ores in Italy, Slovenia, the United States and Mexico which once produced a large proportion of the world's supply have now been completely mined out. The metal is extracted by heating cinnabar in a current of air and condensing the vapor. The equation for this extraction is:

- HgS + O2 â Hg + SO2

In 2005, China was the top producer of mercury with almost two-thirds global share followed by Kyrgyzstan, as reported by the British Geological Survey. Several other countries are believed to have unrecorded production of mercury from copper electrowinning processes and by recovery from effluents.

Due to minimal surface disruption, mercury mines lend themselves to constructive re-use. For example, in 1976 Santa Clara County, California purchased the historic Almaden Quicksilver Mine and proceeded to create a county park on the site, after conducting extensive safety and environmental analysis of the property.

History

Mercury was known to the ancient Chinese and Hindus, and was found in Egyptian tombs that date from 1500 B.C.E. In China, India, and Tibet, mercury use was thought to prolong life, heal fractures, and maintain generally good health. China's first emperor, Qin Shi Huang Di, was driven insane and killed by mercury pills intended to give him eternal life. He is said to have been buried in a tomb that contained rivers of flowing mercury, representative of the rivers of China.

The ancient Greeks used mercury in ointments and the Romans used it in cosmetics. By 500 B.C.E., mercury was used to make amalgams with other metals. The Indian word for alchemy is RasavÄtam which means "the way of mercury."

Alchemists often thought of mercury as the First Matter from which all metals were formed. It seemed to them that different metals could be produced by varying the quality and quantity of sulfur contained within the mercury. The goal of many alchemists was the transmutation of base (or impure) metals into gold, and mercury was thought to be required for this process.

Hat making

From the mid-eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth centuries, a process called "carroting" was used in the making of felt hats. Animal skins were rinsed in an orange solution of the mercury compound mercuric nitrate (Hg(NO3)2·2H2O).[1] This process separated the fur from the pelt and matted it together.

The solution of mercuric nitrate and the vapors it produced were highly toxic. Its use resulted in widespread cases of mercury poisoning among hatters. Symptoms included tremors, emotional lability, insomnia, dementia, and hallucinations. The United States Public Health Service banned the use of mercury in the felt industry in December 1941. The psychological symptoms associated with mercury poisoning may have inspired the phrase "mad as a hatter." Lewis Carroll's "Mad Hatter" in his book, Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, was based on this fact.

Production of chlorine and caustic soda

Chlorine is produced from sodium chloride (common salt, NaCl) using electrolysis to separate metallic sodium from chlorine gas. Usually the salt is dissolved in water to produce a brine. By-products of any such chloralkali process are caustic soda (sodium hydroxide, (NaOH)) and hydrogen (H2).

In the late 1900s, the largest use of mercury[2][3] was in the mercury cell process (also called the Castner-Kellner process), where metallic sodium is formed as an amalgam at a cathode made from mercury; this sodium is then reacted with water to produce sodium hydroxide.[4] Many of the industrial mercury releases of the 1900s came from this process, although modern plants have claimed to be safe in this regard.[3] After about 1985, all new chloralkali production facilities that were built in the United States used either membrane cell or diaphragm cell technologies to produce chlorine.

Dentistry

Elemental mercury is the main ingredient in dental amalgams. Controversy over the health effects from the use of mercury amalgams began shortly after its introduction into the western world, nearly 200 years ago. In 1845, The American Society of Dental Surgeons, concerned about mercury poisoning, asked its members to sign a pledge that they would not use amalgam. The ASDS disbanded in 1865. The American Dental Association, formed three years later, takes the position that "amalgam is a valuable, viable and safe choice for dental patients."[5]

In 1993, the United States Public Health Service reported that "amalgam fillings release small amounts of mercury vapor," but in such a small amount that it "has not been shown to cause any adverse health effects." This position is not shared by all governments and there is an ongoing dental amalgam controversy. A recent review by an FDA-appointed advisory panel rejected, by a margin of 13-7, the current FDA report on amalgam safety, stating the report's conclusions were unreasonable given the quantity and quality of information currently available. Panelists said remaining uncertainties about the risk of so-called silver fillings demanded further research; in particular, on the effects of mercury-laden fillings on children and the fetuses of pregnant women with fillings, and the release of mercury vapor on insertion and removal of mercury fillings.

Medicine

Mercury and its compounds have been used in medicine for centuries, although they are much less common today than they once were, now that the toxic effects of mercury and its compounds are more widely understood.

Mercury(I) chloride (also known as calomel or mercurous chloride) has traditionally been used as a diuretic, topical disinfectant, and laxative. Mercury(II) chloride (also known as mercuric chloride or corrosive sublimate) was once used to treat syphilis (along with other mercury compounds), although it is so toxic that sometimes the symptoms of its toxicity were confused with those of the syphilis it was believed to treat. It was also used as a disinfectant.

Blue mass, a pill or syrup in which mercury is the main ingredient, was prescribed throughout the 1800s for numerous conditions including constipation, depression, child-bearing, and toothaches.[6] In the early twentieth century, mercury was administered to children yearly as a laxative and dewormer, and it was used in teething powders for infants. The mercury-containing organohalide Mercurochrome is still widely used but has been banned in some countries, including the United States.

Since the 1930s, some vaccines have contained the preservative thiomersal (also called thimerosal), which is metabolized or degraded to ethyl mercury. It has been claimed that this mercury-based preservative can cause or trigger autism in children, but scientific studies have not produced firm evidence to support such a link.[7] Nevertheless, thiomersal has been removed from or reduced to trace amounts in all U.S. vaccines recommended for children 6 years of age and under, with the exception of inactivated influenza vaccine.[8]

Mercury in the form of its common ore, cinnabar, remains an important component of Chinese, Tibetan, and Ayurvedic medicine. Recently, less toxic substitutes have been devised for these medicines, so that they can be exported to countries that prohibit the use of mercury in medications.

Today, the use of mercury in medicine has greatly declined in all respects, especially in developed countries. Thermometers and sphygmomanometers (devices used to measure blood pressure) containing mercury were invented in the early eighteenth and late nineteenth centuries, respectively. In the early twenty-first century, their use is declining and has been banned in some countries, states, and medical institutions. In 2002, the U.S. Senate passed legislation to phase out the sale of non-prescription mercury thermometers. In 2003, Washington and Maine became the first states to ban mercury blood pressure devices.[9]

Mercury compounds are found in some over-the-counter drugs, including topical antiseptics, stimulant laxatives, diaper-rash ointment, eye drops, and nasal sprays. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has noted âinadequate data to establish general recognition of the safety and effectivenessâ of the mercury ingredients in these products.[10] Mercury is still used in some diuretics, although substitutes now exist for most therapeutic uses.

Notable characteristics

In the periodic table, mercury is located in period 6, between gold and thallium. In addition, it is in group 12 (former group 2B) below cadmium. At room temperature and pressure mercury is a heavy, silvery liquid.[11] Around room temperature, its density is 13.534 grams per cubic centimeter. Its melting point is -38.83â°C (-37.89â°F), and its boiling point is 356.73â°C (674.11â°F).

Many metals, including gold and zinc, are soluble in mercury, and the mixtures are called amalgams. Iron, however, is an exception to this rule, and iron flasks have been traditionally used to trade mercury.

Reactivity

When heated, mercury reacts with oxygen in the air to form mercury oxide, which undergoes decomposition upon heating to higher temperatures.

In the reactivity series of metals, mercury is below hydrogen and does not react with most dilute acids, such as dilute sulfuric acid. However, oxidizing acidsâsuch as concentrated sulfuric acid, nitric acid, and aqua regiaâdissolve it to give sulfate, nitrate, and chloride. Similar to silver, mercury reacts with atmospheric hydrogen sulfide. Mercury even reacts with solid sulfur flakes, which are used in mercury spill kits to absorb mercury vapors. (Spill kits also use activated charcoal and powdered zinc).

Isotopes

There are seven stable isotopes of mercury, of which Hg-202 is the most abundant (29.86 percent). The longest-lived radioisotopes are 194Hg, with a half-life of 444 years, and 203Hg, with a half-life of 46.612 days. Most of the remaining radioisotopes have half-lives that are less than a day. The isotopes 199Hg and 201Hg are often studied by the technique known as nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR).

Compounds

The most important salts of mercury are:

- Mercury(I) chloride (also called calomel) is sometimes still used in medicine and acousto-optical filters

- Mercury(II) chloride (which is very corrosive, sublimates and is a violent poison)

- Mercury fulminate, (a detonator widely used in explosives)

- Mercury(II) oxide, the main oxide of mercury

- Mercury(II) sulfide (cinnabar mercuric ore still used in oriental medicine, or vermilion which is a high-grade paint pigment)

- Mercury(II) selenide a semiconductor

- Mercury(II) telluride a semiconductor

- Mercury cadmium telluride and mercury zinc telluride, infrared detector materials

Laboratory tests have found that an electrical discharge causes the noble gases to combine with mercury vapor. These compounds are held together with van der Waals forces and result in Hg·Ne, Hg·Ar, Hg·Kr, and Hg·Xe. Organic mercury compounds are also important. Methylmercury is a dangerous compound that is widely found as a pollutant in water bodies and streams.

Applications

- Mercury is used primarily for the manufacture of industrial chemicals and for electrical and electronic applications.

- As noted above, elemental mercury is the main constituent of dental amalgams, although there is continuing controversy over the health effects of amalgams.

- Mercury is used in some thermometers, especially those used to measure high temperatures. (In the United States, non-prescription sale of mercury fever thermometers is banned by a number of different states and localities).

- Mercury barometers, diffusion pumps, coulometers, and many other laboratory instruments. As an opaque liquid with a high density and a nearly linear thermal expansion, it is ideal for this role.

- Mercury is used in sphygmomanometers.

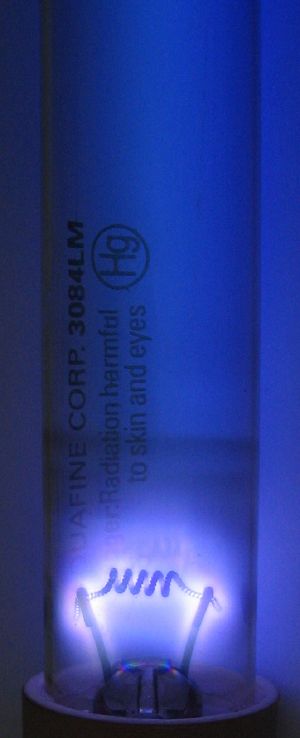

- Gaseous mercury is used in fluorescent lamps, mercury-vapor lamps, and some "neon sign" type advertising signs.

- Liquid mercury was sometimes used as a coolant for nuclear reactors; however, sodium is proposed for reactors cooled with liquid metal, because the high density of mercury requires much more energy to circulate as coolant.

- Mercury was once used in the amalgamation process of refining gold and silver ores. This polluting practice is still used by the garimpeiros (gold miners) of the Amazon basin in Brazil.

- Mercury is still used in some cultures for folk medicine and ceremonial purposes, which may involve ingestion, injection, or the sprinkling of elemental mercury around the home. It must be emphasized that the former two procedures, especially, are extremely hazardous and the latter is nearly so because mercury spreads easily and is therefore ingested.

- Alexander Calder built a mercury fountain for the Spanish Pavilion at the 1937 World's Fair in Paris. The fountain is now on display at the FundaciĂł Joan MirĂł in Barcelona.

- In electrochemistry, mercury is used as part of a secondary reference electrode (called the calomel electrode) as an alternative to the Standard Hydrogen Electrode. This is used to work out the electrode potential of half cells.

- The triple point of mercury (-38.8344 °C) is a fixed point used as a temperature standard for the International Temperature Scale (ITS-90).

- Thiomersal, (called Thimerosal in the United States), is a mercury-containing organic compound used as a preservative in vaccines, though this use is in decline.[12]

- Mercury is used in certain switches, including home Mercury Light Switches installed prior to 1970, tilt switches used in old fire detectors, tilt switches in many modern home thermostats.

- It is used for electrodes in some types of electrolysis (such as for sodium hydroxide and chlorine production) and in some types of batteries (mercury cells), including alkaline batteries).

- It is used in liquid mirror telescopes.

- It is a catalyst in certain chemical reactions.

- It is found in some insecticides.

- In some applications, mercury can be replaced with less toxic but considerably more expensive galinstan alloy.

- A new type of atomic clock, using mercury instead of cesium, has been demonstrated. Accuracy is expected to be within one second in 100 million years.[13][14]

Historical uses:

- Mercury has been used in preserving wood, developing daguerreotypes, silvering mirrors, anti-fouling paints (discontinued in 1990), herbicides (discontinued in 1995), handheld maze games, cleaning, and road leveling devices in cars.

- Mercury compounds have been used in antiseptics, laxatives, antidepressants, and in antisyphilitics.

- In Islamic Spain, it was used for filling decorative pools.[15]

- Mercury was also allegedly used by allied spies to sabotage German planes. A mercury paste applied to bare aluminum would cause the metal to rapidly corrode, leading to structural failures.

- Mercury arc rectifiers were once the most efficient devices to convert alternating current to direct current. These devices became obsolete in the 1970s, with the development of high-voltage solid state devices.

- Mercury was once used as a gun barrel bore cleaner.

- It was also used in wobbler (fishing) lures. Its heavy, liquid form made it useful since the lures made an attractive irregular movement when the mercury moved inside the plug. Such use was stopped due to environmental concerns, but illegal preparation of modern fishing plugs has occurred.

Releases into the environment

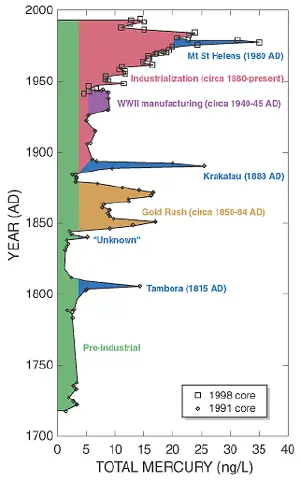

Preindustrial deposition rates of mercury from the atmosphere may be in the range of 4 nanograms per liter (ng/L) in the western USA. Although that can be considered a natural level of exposure, regional or global sources have significant effects. Volcanic eruptions can increase the atmospheric source by 4â6 times.[16]

Mercury enters the environment as a pollutant from various activities:

- Coal-fired power plants are the largest source (40% of U.S. emissions in 1999).[17]

- Small-scale gold mining

- Industrial processes

- Medical applications

- Certain vaccines

- Dentistry

- Cosmetic industries

- Laboratory work involving mercury compounds

Mercury also enters the environment through the disposal of certain products by methods such as landfilling or incineration. Products containing mercury include: auto parts, batteries, fluorescent bulbs, medical products, thermometers, and thermostats.[18] Due to health concerns (see below), toxics use reduction efforts are cutting back or eliminating mercury in such products. For example, most thermometers now use pigmented alcohol instead of mercury. Mercury thermometers are still occasionally used in the medical field because they are more accurate than alcohol thermometers, though both are being replaced by electronic thermometers. Mercury thermometers are still widely used for certain scientific applications because of their greater accuracy and working range.

The environmental impact of mercury released in association with the use of a particular product can sometimes be complicated. For instance, compact fluorescent light bulbs (CFLs) contain small amounts of mercury, whereas incandescent light bulbs contain no mercury. (In 2004, two-thirds of CFLs sold contained 5 mg or less of mercury per bulb, while 96 percent contained 10 mg or less.) Many environmentalists, however, argue in favor of using CFLs because they consume far less electricity than incandescent lamps. They point out that there is mercury in the fly ash emitted by coal power plants, so the less electricity that is consumed, the better.

The United States Clean Air Act, passed in 1990, put mercury on a list of toxic pollutants that need to be controlled to the greatest possible extent. Thus, industries that release high concentrations of mercury into the environment agreed to install maximum achievable control technologies (MACT). In March 2005 EPA rule[19] added power plants to the list of sources that should be controlled and a national cap and trade rule was issued. States were given until November 2006 to impose stricter controls, and several states are doing so. On the other hand, several states subjected the rule to legal challenge in 2005.

Historically, one of the largest releases was from the Colex plant, a lithium-isotope separation plant at Oak Ridge. The plant operated in the 1950s and 1960s. Records are incomplete and unclear, but government commissions have estimated that some two million pounds of mercury are unaccounted for.[20]

One of the worst industrial disasters in history was caused by the dumping of mercury compounds into Minamata Bay, Japan. The Chisso Corporation, a fertilizer and later petrochemical company, was found responsible for polluting the bay from 1932â1968. It is estimated that over 3,000 people suffered various deformities, severe mercury poisoning symptoms, or death from what became known as Minamata disease.

Safety

Mercury and most of its compounds are extremely toxic and are generally handled with care; in cases of spills involving mercury (such as from certain thermometers or a fluorescent light bulbs) specific cleaning instructions should be used to avoid toxic exposure.[21] It can be inhaled and absorbed through the skin and mucous membrane, so containers of mercury are securely sealed to avoid spills and evaporation. Heating of mercury, or compounds of mercury that may decompose when heated, should always be carried out with adequate ventilation in order to avoid exposure to mercury vapor. The most toxic forms of mercury are its organic compounds, such as methylmercury.

Occupational exposure

Due to the health effects of mercury exposure, industrial and commercial uses are regulated in many countries. The World Health Organization, OSHA, and NIOSH all treat mercury as an occupational hazard, and have established specific occupational exposure limits. Environmental releases and disposal of mercury are regulated in the U.S. primarily by the United States Environmental Protection Agency.

A study has shown that acute exposure (4-8 hours) to calculated elemental mercury levels of 1.1 to 44 mg/m3 resulted in chest pain, dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, impairment of pulmonary function, and evidence of interstitial pneumonitis.[22]

Acute exposure to mercury vapor has been shown to result in profound central nervous system effects, including psychotic reactions characterized by delirium, hallucinations, and suicidal tendency. Occupational exposure has resulted in broad-ranging functional disturbance, including erethism, irritability, excitability, excessive shyness, and insomnia. With continuing exposure, a fine tremor develops and may escalate to violent muscular spasms. Tremor initially involves the hands and later spreads to the eyelids, lips, and tongue. Long-term, low-level exposure has been associated with more subtle symptoms of erethism, including fatigue, irritability, loss of memory, vivid dreams, and depression.[23] [24]

Treatment

Research on the treatment of mercury poisoning is limited. Currently available drugs for acute mercurial poisoning include chelators N-acetyl-D,L-penicillamine (NAP), British Anti-Lewisite (BAL), 2,3-dimercapto-1-propanesulfonic acid (DMPS), and dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA). In one small study including 11 construction workers exposed to elemental mercury, patients were treated with DMSA and NAP.[25] Chelation therapy with both drugs resulted in the mobilization of a small fraction of the total estimated body mercury. DMSA was able to increase the excretion of mercury to a greater extent than NAP.

Mercury in fish

Fish and shellfish have a natural tendency to concentrate mercury in their bodies, often in the form of methylmercury, a highly toxic organic compound of mercury. Species of fish that are high on the food chain, such as shark, swordfish, king mackerel, albacore tuna, and tilefish contain higher concentrations of mercury than others. This is because mercury is stored in the muscle tissues of fish, and when a predatory fish eats another fish, it assumes the entire body burden of mercury in the consumed fish. Since fish are less efficient at depurating than accumulating methylmercury, fish-tissue concentrations increase over time. Thus species that are high on the food chain amass body burdens of mercury that can be ten times higher, or more, than the species they consume. This process is called biomagnification. The first occurrence of widespread mercury poisoning in humans occurred this way in Minamata, Japan, now called Minamata disease.

The complexities associated with mercury fate and transport are relatively succinctly described by USEPA in their 1997 Mercury Study Report to Congress. Because methylmercury and high levels of elemental mercury can be particularly toxic to unborn or young children, organizations such as the U.S. EPA and FDA recommend that women who are pregnant or plan to become pregnant within the next one or two years, as well as young children avoid eating more than 6 ounces (one average meal) of fish per week.

In the United States, the FDA has an action level for methyl mercury in commercial marine and freshwater fish that is 1.0 parts per million (ppm), and in Canada the limit for the total of mercury content is 0.5 ppm.

Species with characteristically low levels of mercury include shrimp, tilapia, salmon, pollock, and catfish (FDA March 2004). The FDA characterizes shrimp, catfish, pollock, salmon, and canned light tuna as low-mercury seafood, although recent tests have indicated that up to 6 percent of canned light tuna may contain high levels.[26]

Mercury and aluminium

Mercury readily combines with aluminum to form a mercury-aluminum amalgam when the two pure metals come into contact. However, when the amalgam is exposed to air, the aluminum oxidizes, leaving behind mercury. The oxide flakes away, exposing more mercury amalgam, which repeats the process. This process continues until the supply of amalgam is exhausted, and since it releases mercury, a small amount of mercury can âeat throughâ a large amount of aluminum over time, by progressively forming amalgam and relinquishing the aluminum as oxide.

Aluminum in air is ordinarily protected by a molecule-thin layer of its own oxide, which is not porous to oxygen. Mercury coming into contact with this oxide does no harm. However, if any elemental aluminum is exposed (even by a recent scratch), the mercury may combine with it, starting the process described above, and potentially damaging a large part of the aluminum before it finally ends.

For this reason, restrictions are placed on the use and handling of mercury in proximity with aluminum. In particular, mercury is not allowed aboard aircraft under most circumstances because of the risk of it forming amalgam with exposed aluminum parts in the aircraft.

Regulations

In the European Union, RoHS legislation being introduced will ban mercury from certain electrical and electronic products, and limit the amount of mercury in other products to less than 1000 ppm (except for certain exemptions).

See also

Notes

- â J.D. Lee, Concise Inorganic Chemistry (Williston, VT: Blackwell Publishing Limited, 1999, ISBN 0632052937).

- â The CRB Commodity Yearbook (2000, ISSN 1076-2906).

- â 3.0 3.1 Barry R. Leopold, Chapter 3: Manufacturing Processes Involving Mercury, Use and Release of Mercury in the United States. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â EuroChlor, Chlorine Online Diagram of mercury cell process. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â ADA, Statement on Dental Amalgam. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â Hilary Mayell, Did Mercury in "Little Blue Pills" Make Abraham Lincoln Erratic? National Geographic. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â S.K. Parker, B. Schwartz, J. Todd, L.K. Pickering, Thimerosal-containing vaccines and autistic spectrum disorder: a critical review of published original data, Pediatrics 114 (3): 793â804. Retrieved August 14, 2007. PMID 15342856.

- â FDA, Thimerosal in vaccines. Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â Health Care Without Harm, Two States Pass First-time Bans on Mercury Blood Pressure Devices. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â FDA, Title 21âFood and Drugs Chapter IâFood and Drug Administration Department of Health and Human Services Subchapter DâDrugs for Human Use Code of federal regulations. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â Fred Senese, Why is mercury a liquid at STP? General Chemistry Online at Frostburg State University. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â FDA, Thimerosal in Vaccines. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â BBC, World's most precise clock developed. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â NIST, New Atomic Clock Could Be 1,000 Times Better Than Todayâs Best. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â Tor Eigeland, The City of Al-Zahra, Saudi Aramco World 27: 5. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â USGS, Glacial Ice Cores Reveal A Record of Natural and Anthropogenic Atmospheric Mercury Deposition for the Last 270 Years. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â EPA, What is EPA doing about mercury air emissions? Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â EPA, Mercury-containing Products. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â EPA, Clean Air Mercury Rule. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â HSS, Y-12 Mercury Task Force Files: A Guide to Record Series of the Department of Energy and its Contractors. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â EPA, Guidelines for mercury spills removal. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

- â R.B. McFarland and J. H. Reigel, Occup Med 1978 Aug 20 (8): 532-4.

- â WHO, Environmental Health Criteria 1: Mercury. (Geneva, World Health Organization, 1976).

- â WHO, Inorganic mercury. Environmental Health Criteria 118. (World Health Organization, Geneva, 1991).

- â RE Bluhm, et. al. Hum Exp Toxicol 3 (1992):201-10.

- â Chicago Tribune, FDA tests show risk in tuna. Retrieved August 14, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chang, Raymond. Chemistry, 9th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Science/Engineering/Math, 2006. ISBN 0073221031.

- Cotton, F. Albert, and Geoffrey Wilkinson. Advanced Inorganic Chemistry, 4th ed. New York, NY: Wiley, 1980. ISBN 0471027758.

- Greenwood, N.N., and A. Earnshaw. Chemistry of the Elements, 2nd ed. Burlington, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann, Elsevier Science, 1998. ISBN 0750633654.

- Lee, J.D. Concise Inorganic Chemistry. Williston, VT: Blackwell Publishing Limited, 1999. ISBN 0632052937.

- Los Alamos National Laboratory. Mercury. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

- Kolev, S.T., and N. Bates. Mercury (UK PID). National Poisons Information Service: Medical Toxicology Unit (London Centre), Guy's & St. Thomas' Hospital Trust. March 1996. Retrieved August 11, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2025.

- WebElements.com â Mercury.

- Hg 80 Mercury.

- A summary of the UNEP report by GreenFacts.

- Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC): Mercury Guide â NRDC.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.