Kyrgyzstan

| –ö—č—Ä–≥—č–∑ –†–Ķ—Ā–Ņ—É–Ī–Ľ–ł–ļ–į—Ā—č Kirgiz RespublikasńĪ Kyrgyz Republic |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Kyrgyz Respublikasynyn Mamlekettik Gimni National Anthem of the Kyrgyz Republic |

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Bishkek 42¬į52‚Ä≤N 74¬į36‚Ä≤E | |||||

| Official languages | Kyrgyz (State) Russian (official)[1] |

|||||

| Ethnic groups  | 77.7% Kyrgyz 14.1% Uzbek 3.9% Russian 1.0% Dungans 0.5% Uyghurs 2.8% others[2] |

|||||

| Demonym | Kyrgyz Kyrgyzstani[3] |

|||||

| Government | Unitary presidential republic | |||||

|  -  | President | Sadyr Japarov | ||||

|  -  | Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers | Akylbek Japarov | ||||

| Independence | from the Soviet Union  | |||||

|  -  | Established | October 14, 1924  | ||||

|  -  | Kirghiz SSR | December 5, 1936  | ||||

|  -  | Declared | August 31, 1991  | ||||

|  -  | Recognized | December 25, 1991  | ||||

|  -  | Current constitution | April 11, 2021  | ||||

| Area | ||||||

|  -  | Total | 199,900 km² (86th) 77,181 sq mi  |

||||

|  -  | Water (%) | 3.6 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

|  -  | 2023 estimate | 6,122,781[3] (112th[3]) | ||||

|  -  | Density | 27.4/km² (109th) 71/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate | |||||

|  -  | Total | |||||

|  -  | Per capita | |||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2024 estimate | |||||

|  -  | Total | |||||

|  -  | Per capita | |||||

| Gini (2020) | 29.0[5]  | |||||

| Currency | Som (KGS) |

|||||

| Time zone | KGT (UTC+6) | |||||

| Internet TLD | .kg | |||||

| Calling code | +996 | |||||

Kyrgyzstan (also ‚ÄúKyrgyz,‚ÄĚ ‚ÄúKirgizia,‚ÄĚ or ‚ÄúKirghizia‚ÄĚ), officially the Kyrgyz Republic, is a landlocked and mountainous country in Central Asia. It borders Kazakhstan to the north, Uzbekistan to the west, Tajikistan to the southwest and the People's Republic of China to the southeast.

The name "Kyrgyz," both for the people and for the nation itself, is said to mean "40 girls," a reference to the Manas of folklore unifying 40 tribes against the Mongols.

With a population composed of Kyrgyz, Uzbeks, Tatars, Uyghurs, Kazakhs, Ukrainians, and Russians, and arbitrarily drawn borders intended to play ethnic groups off against each other, Kyrgyzstan lives with ethnic tension that has erupted into violence. Under foreign domination for many centuries (the most recent being the Soviet Union), the beginning of the twenty-first century sees Kyrgyzstan struggling to recover and gain a foothold in the modern world.

Geography

The smallest of the newly independent Central Asian states, Kyrgyzstan is about the same size as the state of the U.S. state of Nebraska, with a total area of about of 77,181 square miles (199,900 square kilometers). The national territory extends about 900 kilometers from east to west and 410 kilometers from north to south.

The mountainous region of the Tian Shan covers over 80 percent of the country. Kyrgyzstan is occasionally referred to as "the Switzerland of Central Asia" as a result. The remainder is made up of valleys and basins.

The highest peaks are in the Kakshaal-Too range, forming the Chinese border. Peak Jengish Chokusu, at 24,400 feet (7439 meters), is the highest point. Heavy snowfall in winter leads to spring floods that often cause serious damage downstream. The run-off from the mountains is used for hydro-electricity.

The climate varies regionally. The south-western Fergana Valley is subtropical and extremely hot in summer, with temperatures reaching 104¬įF (40¬įC). The northern foothills are temperate and the Tian Shan varies from dry continental to polar climate, depending on elevation. In the coldest areas, temperatures are sub-zero for around 40 days in winter, and even some desert areas experience constant snowfall in this period.

Lake Issyk-Kul in the north-western Tian Shan is the largest lake in Kyrgyzstan and the second largest mountain lake in the world after Titicaca.

The principal river is the Naryn, flowing west through the Fergana Valley into Uzbekistan, where it meets another of Kyrgyzstan's major rivers, the Kara Darya, forming the Syr Darya which eventually flows into the Aral Sea. The massive extraction of water for irrigating Uzbekistan's cotton fields now causes the river to dry up long before reaching the Sea. The Chu River also briefly flows through Kyrgyzstan before entering Kazakhstan.

Kyrgyzstan has significant deposits of metals including gold and rare earth metals. Due to the country's mountainous terrain, less than eight percent of the land is cultivated, and this is concentrated in the northern lowlands and the fringes of the Fergana Valley.

Natural hazards include earthquakes, and major flooding during the snow melt.

Although Kyrgyzstan has abundant water running through it, its water supply is determined by a post-Soviet sharing agreement among the five Central Asian republics. As in the Soviet era, Kyrgyzstan has the right to 25 percent of the water that originates in its territory, but the new agreement allows Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan unlimited use of the water that flows into them from Kyrgyzstan, with no compensation for the nation at the source. Kyrgyzstan uses the entire amount to which the agreement entitles it. Utilization is skewed heavily in favor of agricultural irrigation.

Environmental issues include: Nuclear waste, left behind by the Soviet Union in many open-air pits in hazardous locations; water pollution, since many people get their water directly from contaminated streams and wells; water-borne diseases; increasing soil salinity from faulty irrigation practices; and illegal hunting of rare species, such as the snow leopard and the Marco Polo sheep.

Bishkek in the north is the capital and largest city, with 900,000 inhabitants in 2005. The second city is the ancient town of Osh, located in the Fergana Valley near the border with Uzbekistan.

History

Stone implements found in the Tian Shan mountains indicate the presence of human society in what is now Kyrgyzstan from 200,000 to 300,000 years ago. The first written records of a civilization in the area appear in Chinese chronicles beginning about 2000 B.C.E.

Kyrgyz history dates back to 201 B.C.E. The early Kyrgyz lived in the upper Yenisey River valley in central Siberia. The discovery of the Pazyryk and Tashtyk cultures show them as a blend of Turkic and Iranian nomadic tribes. Chinese and Muslim sources of the seventh through twelfth centuries C.E. describe the Kyrgyz as red-haired with fair complexion and green-blue eyes.

The first Turks to form a state in Central Asia were G√∂kt√ľrks or K√∂k-T√ľrks. Known in medieval Chinese sources as Tujue (Á™ĀŚé• t√ļ ju√©), the G√∂kt√ľrks under the leadership of Bumin Khan (d. 552) and his sons established the first known Turkic state around 552 C.E. in an area that had earlier been occupied by the Xiongnu. They expanded rapidly to rule wide territories in Central Asia. The G√∂kt√ľrks split in two rival Khanates, of which the western one disintegrated in 744 C.E.

The first kingdom to emerge from the G√∂kt√ľrks khanate was the Buddhist Uyghur Empire that flourished in Central Asia from 740 to 840 C.E.

After the Uyghur empire disintegrated a branch of the Uyghurs migrated to oasis settlements in the Tarim Basin and Gansu, and set up a confederation of decentralized Buddhist states called Kara-Khoja. Others, closely related to Uyghurs (Qarluks), occupying the western Tarim Basin, Ferghana Valley, Jungaria and parts of modern Kazakhstan bordering the Muslim Turco-Tajik Khwarazm Sultanate, converted to Islam no later than the tenth century and built a federation with Muslim institutions called Kara-Khanlik, whose princely dynasties are called Karakhanids. Its capital, Balasagun flourished as a cultural and economic center.

The Islamized Qarluk princely clan, the Balasaghunlu Ashinalar (or the Karakhanids) gravitated toward the Persian Islamic cultural zone after their political autonomy in Central Asia was secured during the ninth-to-tenth centuries.

The Mongol invasion of Central Asia in the thirteenth century devastated the territory of Kyrgyzstan, costing its people their independence and their written language. The son of Genghis Khan, Juche, conquered the Kyrgyz tribes of the Yenisey region. At that time, the area of present Kyrgyzstan was an important link in the Silk Road.

For the next 200 years, the Kyrgyz remained under the Golden Horde, and the Oriot and Jumgar khanates that succeeded that regime. Freedom was regained in 1510, but Kyrgyz tribes were overrun in the seventeenth century by the Kalmyks, in the mid-eighteenth century by the Manchus, and in the early nineteenth century by the Uzbeks.

In the early nineteenth century, the southern part of what is today Kyrgyzstan came under the control of the Khanate of Kokand. The territory, then known in Russian as "Kirgizia," was formally incorporated into the Russian Empire in 1876. The Russian takeover instigated numerous revolts against tsarist authority, and many of the Kyrgyz opted to move to the Pamirs and Afghanistan.

A 1916 rebellion in Central Asia was suppressed, causing many Kyrgyz to migrate to China. Since many ethnic groups in the region were (and still are) split between neighboring states, at a time when borders were less regulated, it was common to move back and forth over the mountains, depending on where life was perceived as better.

Soviet power was initially established in the region in 1919 and the Kara-Kyrgyz Autonomous Oblast was created within the Russian SFSR. The term Kara-Kirghiz was used until the mid-1920s by the Russians to distinguish them from the Kazakhs, who were also referred to as Kirghiz. On December 5, 1936, the Kyrgyz Soviet Socialist Republic was established as a full republic of the Soviet Union.

During the 1920s, Kyrgyzstan developed considerably in cultural, educational, and social life. Literacy was greatly improved, and a standard literary language was introduced. Economic and social development was notable. Many aspects of the Kyrgyz national culture were retained despite the suppression of nationalist activity under Stalin.

The early years of glasnost (a 1985 Soviet Union policy of openness) had little effect on the political climate in Kyrgyzstan. However, the Republic's press adopted a more liberal stance and a new publication, Literaturny Kirghizstan, by the Union of Writers was established. Several groups that emerged in 1989 to deal with the acute housing crisis were permitted.

In June 1990, ethnic tensions between Uzbeks and Kyrgyz surfaced in the Osh Oblast, where Uzbeks form a majority. Violent confrontations ensued, and a curfew was introduced. Order was not restored until August 1990.

By the early 1990s, the Kyrgyzstan Democratic Movement (KDM) had developed into a significant political force. In an upset victory, Askar Akayev, the liberal President of the Kyrgyz Academy of Sciences, was elected to the presidency in October 1990. The following January, Akayev introduced new government structures and appointed a new government comprised mainly of younger, reform-oriented politicians.

In December 1990, the Supreme Soviet voted to change the republic's name to the Republic of Kyrgyzstan. (In 1993, it became the Kyrgyz Republic.) In February 1991, the name of the capital, Frunze, was changed back to its pre-revolutionary name of Bishkek. But economic realities worked against secession from the Soviet Union. In a referendum on the preservation of the Soviet Union in March 1991, 88.7 percent of the voters approved the proposal to retain the Soviet Union as a "renewed federation."

On August 19, 1991, when the State Emergency Committee assumed power in Moscow, there was an attempt to depose Akayev in Kyrgyzstan. The coup collapsed the following week. Akayev and Vice President German Kuznetsov resigned from the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU), and the entire bureau and secretariat resigned. A Supreme Soviet vote declared independence from the Soviet Union on August 31, 1991.

In October 1991, Akayev ran unopposed and was elected president of the independent republic. On December 21, 1991, Kyrgyzstan joined the other four Central Asian Republics to formally enter the new Commonwealth of Independent States. In 1992, Kyrgyzstan joined the United Nations and the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe.

The "Tulip Revolution," after the parliamentary elections in March 2005, forced President Akayev's resignation on April 4, 2005. Opposition leaders formed a coalition and a new government was formed under President Kurmanbek Bakiyev and Prime Minister Feliks Kulov.

Political stability appears to be elusive, however, as various factions allegedly linked to organized crime are jockeying for power. Three of the 75 members of parliament elected in March 2005 were assassinated, and another member was assassinated on May 10, 2006 shortly after winning his murdered brother's seat in a by-election. All four are reputed to have been directly involved in illegal business ventures.

Politics

The politics of Kyrgyzstan take place in the framework of a presidential system representative democratic republic, whereby the President is head of state and the Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers is head of government. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and parliament.

The constitution was adopted in 1993, amended in 2003 to expand the powers of the president, amended again during demonstrations in November 2006, granting greater powers to the parliament, and re-amended, in December 2006, returning some power to the president. In April 2021, the majority of voters approved in the constitutional referendum a new constitution that will give new powers to the president, significantly strengthening the power of the presidency.

The president is elected by popular vote for a five-year term, and is eligible for a second term. The Cabinet of Ministers is an executive body presided by the Chairman of the Cabinet of Ministers of Kyrgyzstan (formerly known as the Prime Minister). The cabinet consists of the deputy chairmen, ministers, and the chairmen of state committees.

The Kyrgyzstan Parliament approved a smaller executive cabinet, consolidating several ministries and reducing their number from 22 to 16 on February 3, 2021; this was partially in response to the political unrest which swept the nation in October 2020.

The judiciary comprises a supreme court, a constitutional court, a higher court of arbitration and local courts. Judges of both the supreme and constitutional courts are appointed for 10-year terms by the Jorgorku Kenesh on the recommendation of the president. Their age limit is 70 years. Judges for other courts are appointed by the president on the recommendation of the National Council on Legal Affairs for a probationary period of five years, then 10 years. The legal system is based on a civil law system

Corruption problems have plagued the country since its independence from the Soviet Union. Several members of parliament have been murdered.

Current concerns include privatization of state-owned enterprises, expansion of democracy and political freedoms, inter-ethnic relations, and terrorism.

Administrative divisions

Kyrgyzstan is divided into seven provinces or oblast (plural oblasttar) administered by appointed governors. The capital, Bishkek, is administratively an independent city (shaar) with a status equal to a province.

The provinces, and capital city, are as follows: Bishkek, 1; Batken, 2; Chui-Tokmok, 3; Jalal-Abad, 4; Naryn, 5; Osh, 6; Talas, 7; Issyk Kul, 8.

Each province comprises a number of districts (rayon'), administered by government-appointed officials (akim). Rural communities (ayńĪl √∂km√∂t√ľ), consisting of up to 20 small settlements, have their own elected mayors and councils.

Enclaves and exclaves

An ‚Äúenclave‚ÄĚ is a country or part of a country mostly surrounded by the territory of another country or wholly lying within the boundaries of another country, and an ‚Äúexclave‚ÄĚ is one that is geographically separated from the main part by surrounding alien territory.

There is one exclave, the tiny village of Barak, (population 627) in the Fergana valley. The village is surrounded by Uzbek territory and located between the towns of Margilan and Fergana.

There are four Uzbek enclaves within Kyrgyzstan. The town of Sokh has an area of 125 square miles and a population of 42,800 in 1993. A total 99 percent are Tajiks, and the remainder Uzbeks. Shakhrimardan has an area 35 square miles (90km²) and a population of 5100 in 1993. A total of 91 percent are Uzbeks, the remainder Kyrgyz. The tiny territory of Chuy-Kara is roughly two miles by 0.6 miles (3km long by 1 km wide), and Dzhangail (a dot of land barely 2 or 3 km across).

There are two enclaves belonging to Tajikistan. Vorukh has an area of between 37 and 50 miles (95 and 130km²) and a population estimated between 23,000 and 29,000 people. A total of 95 percent are Tajiks and five percent are Kyrgyz. They are distributed among 17 villages), located 28 miles (45km) south of Isfara. There is a small settlement near the Kyrgyz railway station of Kairagach.

Military

The army of Kyrgyzstan includes brigades at Osh and Koi-tash, in the Bishkek area, a special forces brigade, and other units. Air Defense includes a regiment of MiG-21s and Aero L-39s, four Antonov transports, and a helicopter squadron. There are security forces and border troops. Military expenditures total $19.2-million a year, or 1.4 percent of GDP.

A United States Air Force installation operated at Manas International Airport near Bishkek from December 2001 until June 2014, when American troops vacated the base and it was handed over back to the Kyrgyzstan military.

Economy

The Kyrgyz Republic's economy was severely affected by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the resulting loss of its vast market. In 1990, some 98 percent of Kyrgyz exports went to other parts of the Soviet Union. Thus, the nation's economic performance in the early 1990s was worse than any other former Soviet republic except war-torn Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Tajikistan, as factories and state farms collapsed with the disappearance of their traditional markets in the former Soviet Union. While economic performance has improved considerably in the last few years, and particularly since 1998, difficulties remain in securing adequate fiscal revenues and providing an adequate social safety net.

The government has reduced expenditures, ended most price subsidies, and introduced a value-added tax. Overall, the government appears committed to the transition to a market economy. Through economic stabilization and reform, the government seeks to establish a pattern of long-term consistent growth. Reforms led to the Kyrgyz Republic's accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1998.

Agriculture is an important sector of the economy in the Kyrgyz Republic. By the early 1990s, the private agricultural sector provided between one-third and one-half of some harvests. In 2002 agriculture accounted for 35.6 percent of GDP and about half of employment.

The Kyrgyz Republic's terrain is mountainous, which accommodates livestock raising, the largest agricultural activity, so the resulting wool, meat, and dairy products are major commodities. Main crops include wheat, sugar beets, potatoes, cotton, tobacco, vegetables, and fruit. As the prices of imported agrichemicals and petroleum are so high, much farming is being done by hand and by horse, as it was generations ago. Agricultural processing is a key component of the industrial economy, as well as one of the most attractive sectors for foreign investment.

Farmland cannot be owned by individuals, but land rights may be held for up to 99 years. Uncertain land tenure and overall financial insecurity have caused many private farmers to concentrate their capital in livestock, thus subjecting new land to the overgrazing problem.

The Kyrgyz Republic is rich in mineral resources but has negligible petroleum and natural gas reserves; it imports petroleum and gas. Among its mineral reserves are substantial deposits of coal, gold, uranium, antimony, and other rare-earth metals. Metallurgy is an important industry, and the government hopes to attract foreign investment in this field. The government has actively encouraged foreign involvement in extracting and processing gold. The Kyrgyz Republic's plentiful water resources and mountainous terrain enable it to produce and export large quantities of hydroelectric energy.

A large amount of local commerce occurs at bazaars and small village kiosks. Commodities such as gas (petrol) are often sold on the road-side in gallon jugs. A significant amount of trade is unregulated. There is also a scarcity of common everyday consumer items in remote villages. Thus a large number of homes are quite self-sufficient with respect to food production. There is a distinct differentiation between urban and rural economies.

Demographics

The country is rural; only about one-third of Kyrgyzstan's population live in urban areas. The average population density is 69 people per square mile (29 people per square kilometer).

Ethnicity

Kyrgyzstan has undergone a pronounced change in its ethnic composition since independence. The percentage of ethnic Kyrgyz has increased from around 50 percent in 1979 to over 70 percent, while the percentage of other ethnic groups, such as Russians, Ukrainians, Germans, and Tatars dropped significantly. Since 1991, a large number of Volga Germans community exiled there by Soviet president Josef Stalin from the Volga German Republic, have mostly returned to Germany.

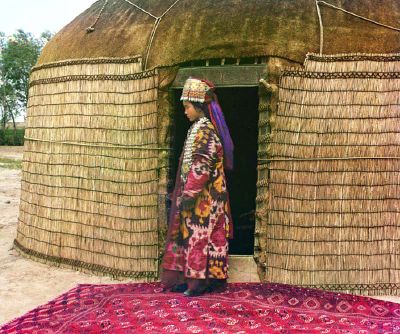

Today the Kyrgyz, a Turkic peoples, comprise the majority of the population. They have historically been semi-nomadic herders, living in round tents called yurts and tending sheep, horses, and yaks. This nomadic tradition continues to function seasonally as herding families return to the high mountain pasture (or jailoo) in the summer. The retention of this nomadic heritage and the freedoms that it assumes continue to have an impact on the political atmosphere in the country.

Other ethnic groups include Russians, concentrated in the north, and Uzbeks, living in the south. Small but noticeable minorities include Tatars, Uyghurs, Kazakhs, and Ukrainians. There are some Dungans, Chinese-speaking Muslim people of Hui origin.

Stalin intentionally drew borders inconsistent with the traditional locations of ethnic populations, leaving large numbers of ethnic Uzbeks and Turkmen within Kyrgyzstan's borders. This was to maintain a level of ethnic tension, in order to avert an uprising.

Religion

Kyrgyzstan is a secular state. During Soviet times, atheism was encouraged. The majority of the population are Sunni Muslims of the Hanafi school. Islam in Kyrgyzstan is more of a cultural background than a devout daily practice for most. The main Christian churches are Russian Orthodox and Ukrainian Orthodox.

Animistic traditions survive. Professional shamans, called bakshe, persist, and usually there are elders who practice shamanistic rituals for families and friends. Buddhist influences, such as the tying of prayer flags onto sacred trees, remain. A small number of Bukharian Jews had lived in Kyrgyzstan, but during the collapse of the Soviet Union most fled to other countries, mainly the United States and Israel.

Graves and natural springs are holy places. Cemeteries stand on hilltops, and graves are marked with elaborate buildings made of mud, brick, or wrought iron. Burials are done in Islamic fashion, but, contrary to Islamic law, the body will remain on display for two or three days. A traditional boz-ui round, domed tent made of wool felt is erected, and the body is laid out inside. The Kyrgyz believe that the spirits of the dead can help or hinder living relatives.

Languages

The Kyrgyz language became an official language in 1991. Kyrgyz is a member of the Turkic group of languages and was written in the Arabic alphabet until the twentieth century. Latin script was introduced and adopted in 1928, and was subsequently replaced by Cyrillic in 1941. Until recently, Kyrgyz remained a language spoken at home, rarely during meetings or other events. However, most parliamentary meetings are conducted in Kyrgyz, with simultaneous interpretation available for those not speaking Kyrgyz.

Kyrgyzstan is one of two of the five former Soviet republics in Central Asia to retain Russian as an official language (Kazakhistan is the other). Russian is widely spoken, except for some remote mountain areas. Russian is mother tongue to the majority of Bishkek dwellers, and most business and political affairs are carried out in this language.

Men and women

Soviet policies maintained a tradition of equality between men and women, and provided women with jobs outside the home and a role in politics. Women continue work mainly in education and agriculture, and are responsible for all work inside the home, where they make decisions on running the household. Men dominate business and politics.

Marriage and the family

Arranged marriages are no longer common. Couples, who are expected to marry in their early twenties, choose each other, marry after a few months, and have children quickly. The bride is required to have a dowry, comprising clothing, sleeping mats, pillows, and a hand-made tush kyiz rug. The groom is required to pay a bride price in the form of cash and several animals‚ÄĒsome cash may go toward the dowry, and the animals may become part of the wedding feast.

A wedding lasts three days. On day one, the bride and groom go to the city with friends to have the marriage license signed. On day two, the bride and groom celebrate separately with their friends and family. On the third day, the bride and her family go to the groom's family's house, where there are celebrations and games. Gifts are exchanged. At the end of the night, a bed is made from the bride's dowry. Two female relatives of the groom ensure the marriage is consummated and that the bride was a virgin. The couple will live with his family until they can afford a house.

Illegal but still practiced is the tradition of wife-stealing. A man may kidnap any unmarried girl 15 years of age and over. The girl spends a night alone with the man. The next day she is taken to meet her mother-in-law, who ties a scarf around the girl's head show she is married. The kidnapped girl may run away, and may sue, but it is shameful to do so. A lesser bride price is paid, but a dowry is not provided.

Polygamy is not practiced, but married people, mostly men, do have lovers. More than one in five couples get divorced. Two people from the same tribe may not marry.

A family often consists of grandparents, parents, and children. Individuals live with their parents until they marry. Three or more children are common, with larger families in rural areas.

The youngest son lives with and cares for his parents until they die, when he inherits the house and the livestock. He may or may not share this inheritance with his brothers. Daughters do not inherit from their parents since they belong to their husbands' families.

Mothers care for their babies. An infant cannot be taken outside the home or be seen by anyone but the immediate family for the first 40 days. Infants are strapped into their cradles much of the time. Children are expected to be quiet. Girls take on household duties from age six, and by the time she is 16, the eldest daughter may be running the household. Boys are rowdy and active and have fewer household chores. Respect is most important.

It is generally considered that there are 40 Kyrgyz clans. This is symbolized by the 40-rayed yellow sun in the center of the flag of Kyrgyzstan. The lines inside the sun are said to represent a yurt (dwelling).

Education

Education is compulsory for nine years for both boys and girls. Public schools are found in all towns and villages, and they offer schooling from first to eleventh grade. There are four years of primary education, starting at the age of six. This is followed by five years of lower secondary education.

Further studies are possible in specialist secondary schools, technical and vocational schools. Higher education is valued but expensive, and there is little financial aid.

The 33 tertiary institutes include the Kyrgyz State National University, the country’s largest university, the Kyrgyz-Russian Slavic University, the American University of Central Asia, and the Bishkek Humanities University.

Kyrgyzstan has a high literacy rate of 99 percent. However, its ambitious program to restructure the Soviet educational system is hampered by low funding and loss of teachers. The Kyrgyz language is increasingly used for instruction. The transition from Russian to Kyrgyz has been hampered by lack of textbooks.

Culture

Government and urban architecture is in the Soviet style. Urban housing consists of large apartment blocks, where families live in two- or three-room apartments. Most rural houses are single story, with open-ended peaked roofs used as storage space. Families live in fenced compounds that include the main house, an outdoor kitchen, barns for animals, sheds for storage, gardens, and fruit trees. The traditional portable collapsible boz-ui dwellings, made of wool felt on a wooden frame, are still used during summer pasturing. The floors and walls of dwellings throughout the country are lined with carpets and fabric hangings. Furniture usually is placed along the walls, leaving most of a room empty.

Food and drink

Mutton is the favorite meat, although it is not always affordable. Beef, chicken, turkey, and goat are also eaten. A noodle dish, laghman (hand-rolled noodles in a broth of meat and vegetables) is popular, as is manti (dumplings filled with either onion and meat, or pumpkin), pelmeni, (a Russian dish of small meat-filled dumplings in broth), ashlam-foo (cold noodles topped with vegetables in spicy broth and pieces of congealed corn starch), samsa (meat or pumpkin-filled pastries), and fried meat and potatoes, and the rice dish pulau or plov, (rice fried with carrots and topped with meat). The most well-known drink is fermented mare's milk, kumis.

Each day most people eat one large meal, and three or four small meals mostly consisting of tea, bread, snacks, and condiments. These include vareynya (jam), kaimak, (similar to clotted cream), sara-mai (a form of butter), and various salads. Bread is considered sacred, and must never be placed on the ground or thrown away. A meal is ended with a quick prayer from the Qur'an. The hands are held out, palms up, and then everyone covers their face while saying "omen."

Textiles

Kyrgyz women produce a wide range of textiles, mostly from the felt of their sheep. Ancient patterns are adapted to the tourist and export market, but it is still a living tradition, in that all yurts and most houses contain hand-made carpets or rugs called shirdaks. Tush kyiz are large, elaborately embroidered wall hangings, traditionally made in Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstan by elder women to commemorate the marriage of a son or daughter. The tush kyiz is hung in the yurt over the marriage bed of the couple.

Flowers, plants, animals, stylized horns, national designs and emblems of Kyrgyz life are often found in these ornate and colorful embroideries. Designs are sometimes dated and signed by the artist upon completion of the work, which may take years to finish.

Literary works

Manas is a traditional epic poem of the Kyrgyz people and the name of the epic's eponymous hero. The poem, with close to half a million lines, is 20 times longer than Homer's Odyssey and one of the longest epics in the world, is a patriotic work recounting the exploits of Manas and his descendants and followers, who fought against the Chinese and Kalmyks in the ninth century to preserve Kyrgyz independence.

Kyrgyz was not written until the twentieth century, when novel-writing in the historical and romance genres developed. Kyrgyz novelist Chingiz Aitmatov is known for his critical novels about life in Soviet Central Asia.

Performing arts

Kyrgyz folk singing and music lessons are taught at school, and there are several Kyrgyz children's performance groups. Instruments include the komuz (a three-stringed lute), oz-komuz (mouth harp), the chopo choor (clay wind instrument), and the kuiak (a four-stringed instrument played with a bow). Popular television shows feature Kyrgyz pop and folk singers and musicians. There is a small but active film industry.

Horse riding

The traditional national sports reflect the importance of horse riding. Very popular, as in all of Central Asia, is buzkashi (meaning "blue wolf"), a cross between polo and rugby football on horseback, in which the two teams attempt to deliver the headless carcass of a goat across the opposition's goal line or, in today's somewhat more regulated version, into the opposition's goal, a big tub or a circle marked on the ground. During a match the players seek to wrestle the goat from their opponents.

Other popular games on horseback are tyiyn or tenghe enish (picking up a coin from the ground at full gallop), kyz kuumai (chasing a girl in order to win a kiss from her, while she gallops away and may lash the pursuer with her horse whip), Oodarysh (wrestling on horseback), long-distance horse races over 15, 20 or even 50 and 100 kilometers, and others.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Kyrgyzstan's Constitution of 2010 with Amendments through 2016: Article 10 Constitute. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ Statistical Yearbook of the Kyrgyz Republic National Statistical Committee of the Kyrgyz Republic. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 3.0 3.1 3.2 CIA, Kyrgyzstan: People and Society The World Factbook. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition. (Kyrgyzstan) International Monetary Fund. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ‚ÜĎ GINI index (World Bank estimate) - Kyrgyz Republic The World Bank. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abazov, Rafis. Historical Dictionary of Kyrgyzstan. Asian/Oceanian historical dictionaries, no. 49. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press, 2004. ISBN 0810848686

- Anderson, John. Kyrgyzstan: Central Asia's island of democracy? [Australia]: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1999. ISBN 9057023903

- Bauer, Armin. A Generation at Risk: Children in the Central Asian republics of Kazakstan and Kyrgyzstan. Manila, Philippines: Asian Development Bank, 1998. ISBN 9715610978

- Harmon, Daniel E. Kyrgyzstan. Growth and influence of Islam in the nations of Asia and Central Asia. Philadelphia: Mason Crest, 2005. ISBN 1590848837

- Kadyrov, V. Kyrgyzstan: Traditions of Nomads. Bishkek: Rarity Ltd, 2005. ISBN 9967424427

External links

All links retrieved March 7, 2025.

- Kyrgyzstan Countries and their Cultures.

- Images of Kyrgyzstan Photos by Jonathan Barth.

- Kyrgtzstan The World Factbook.

- Kyrgyzstan US Department of State.

- Kyrgyzstan Human Rights Watch.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.