Physician

- "Medical doctor" redirects here.

| Physician | |

The Doctor by Luke Fildes (detail) | |

| Occupation | |

|---|---|

| Names | Physician, medical practitioner, medical doctor or simply doctor |

| Occupation type | Professional |

| Activity sectors | Medicine, health care |

| Description | |

| Competencies | The ethics, art and science of medicine, analytical skills, and critical thinking |

| Education required | MBBS, MD, MDCM, or DO |

| Fields of employment | Clinics, hospitals |

| Related jobs | General practitioner Family physician Surgeon Specialist physician |

A physician (American English), medical practitioner (Commonwealth English), medical doctor, or simply doctor, is a professional who practices medicine with the purpose of promoting, maintaining, or restoring health through the study, diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of disease, injury, and other physical and mental impairments. Physicians may focus their practice on certain disease categories, types of patients, and methods of treatmentâknown as specialtiesâor they may assume responsibility for the provision of continuing and comprehensive medical care to individuals, families, and communitiesâknown as general practice.

Both the role of the physician and the meaning of the word itself vary around the world. Degrees and other qualifications vary widely, but there are some common elements, such as medical ethics requiring that physicians show consideration, compassion, and benevolence for their patients. The common purpose of all physicians is to use their skill and knowledge to heal the sick and injured to the best of their ability, and to "do no harm," thus serving the greater good of human society.

Meanings of the term

The term physician is at least nine hundred years old in English: physicians and surgeons were once members of separate professions, and traditionally were rivals. The Shorter Oxford English Dictionary gives a Middle English quotation making this contrast, from as early as 1400: "O Lord, whi is it so greet difference betwixe a cirugian and a physician."[1]

Henry VIII granted a charter to the London Royal College of Physicians in 1518. It was not until 1540 that he granted the Company of Barber-Surgeons (ancestor of the Royal College of Surgeons) its separate charter. In the same year, the English monarch established the Regius Professorship of Physic at the University of Cambridge.[2] Newer universities would probably describe such an academic as a professor of internal medicine. Hence, in the sixteenth century, physic meant roughly what internal medicine does now.

In modern English, the term physician is used in two main ways, with relatively broad and narrow meanings respectively. This is the result of history and is often confusing. These meanings and variations are explained below.

Physician and surgeon

The combined term "physician and surgeon" is used to describe either a general practitioner or any medical practitioner irrespective of specialty.[3][1] This usage still shows the original meaning of physician and preserves the old difference between a physician, as a practitioner of physic, and a surgeon, who practices surgery.

Physician as specialist in internal medicine

Internal medicine or general internal medicine (in Commonwealth nations) is the medical specialty dealing with the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of internal diseases. Physicians specializing in internal medicine are called "internists," or simply physicians (without a modifier) in Commonwealth nations. This meaning of physician as a specialist in internal medicine or one of its many sub-specialties (especially as opposed to a specialist in surgery) conveys a sense of expertise in treatment by drugs or medications, rather than by the procedures of surgeons.[3]

This original use of the term physician, as distinct from surgeon, is common in most of the world including the United Kingdom and other Commonwealth countries (such as Australia, Bangladesh, India, New Zealand, Pakistan, South Africa, Sri Lanka, and Zimbabwe), as well as in places as diverse as Brazil, Hong Kong, Indonesia, Japan, Ireland, and Taiwan. In such places, the more general English terms doctor or medical practitioner are prevalent, describing any practitioner of medicine. In Commonwealth countries, specialist pediatricians and geriatricians are also described as specialist physicians who have sub-specialized by age of patient rather than by organ system.[5]

Another term, hospitalist, was introduced in 1996 to describe US specialists in internal medicine who work largely or exclusively in hospitals.[6]

North America

In the United States and Canada, the term physician describes all medical practitioners holding a professional medical degree. The American Medical Association, established in 1847, as well as the American Osteopathic Association, founded in 1897, both currently use the term physician to describe members. However, the American College of Physicians, established in 1915, does not: This organization uses physician in its original sense, to describe specialists in internal medicine.

Primary care physicians

Primary care physicians guide patients in preventing disease and detecting health problems early while they are still treatable.[7] They are divided into two types: family medicine doctors and internal medicine doctors. Family doctors, or family physicians, are trained to care for patients of any age, while internists are trained to care for adults.[8] Family doctors receive training in a variety of care and are therefore also referred to as general practitioners.[9] Family medicine grew out of the general practitioner movement of the 1960s in response to the growing specialization in medicine that was seen as threatening to the doctor-patient relationship and continuity of care.[10]

Podiatric physicians

Also in the United States, the American Podiatric Medical Association (APMA) defines podiatrists as physicians and surgeons that fall under the department of surgery in hospitals. [11] They undergo training that is similar to that of other physicians, obtaining the Doctor of Podiatric Medicine (DPM) degree.

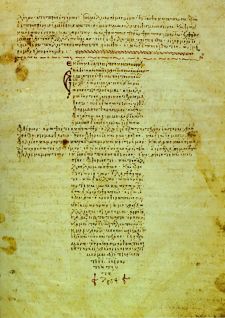

Hippocratic Oath

The Hippocratic Oath is an oath of ethics historically taken by physicians. It is one of the most widely known of Greek medical texts. The oath is arguably the best known text of the Hippocratic Corpus, although most modern scholars do not attribute it to Hippocrates himself, estimating it to have been written in the fourth or fifth century B.C.E. In its original form, it requires a new physician to swear, by a number of healing gods, to uphold specific ethical standards. The oath is the earliest expression of medical ethics in the Western world, establishing several principles of medical ethics which remain of paramount significance today. These include the principles of medical confidentiality and non-maleficence. As the seminal articulation of certain principles that continue to guide and inform medical practice, the ancient text is of more than historic and symbolic value. Swearing a modified form of the oath remains a rite of passage for medical graduates in many countries.

The exact phrase, the famous summary of the oath, "First do no harm" (Latin: Primum non nocere) is not a part of the original Hippocratic oath. Although the phrase does not appear in the 245 C.E. version of the oath, similar intentions are vowed by the original phrase "I will abstain from all intentional wrong-doing and harm." The actual phrase "primum non nocere" is believed to date from the seventeenth century.

Another equivalent phrase is found in Epidemics, Book I, of the Hippocratic school: "Practice two things in your dealings with disease: either help or do not harm the patient."[12]

Education and training

Medical education and career pathways for doctors vary considerably across the world. Medical practice properly requires both a detailed knowledge of the academic disciplines, such as anatomy and physiology, underlying diseases and their treatmentâthe science of medicineâand also a decent competence in its applied practiceâthe art or craft of medicine.

All medical practitioners

Medical practitioners hold a medical degree specific to the university from which they graduated. This degree qualifies the medical practitioner to become licensed or registered under the laws of that particular country, and sometimes of several countries, subject to requirements for internship or conditional registration.

In all developed countries, entry-level medical education programs are tertiary-level courses, undertaken at a medical school attached to a university. Depending on jurisdiction and university, entry may follow directly from secondary school or require prerequisite undergraduate education. The former commonly takes five or six years to complete. Programs that require previous undergraduate education (typically a three- or four-year degree, often in science) are usually four or five years in length. Hence, gaining a basic medical degree may typically take from five to eight years, depending on jurisdiction and university.

Following completion of entry-level training, newly graduated medical practitioners are often required to undertake a period of supervised practice before full registration is granted, typically one or two years. This may be referred to as an "internship", as the "foundation" years in the UK, or as "conditional registration." Some jurisdictions require residencies for practice.

The vast majority of physicians trained in the United States have a Doctor of Medicine degree, and use the initials M.D. A smaller number attend Osteopathic schools and have a Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine degree and use the initials D.O.[13] After completion of medical school, physicians complete a residency in the specialty in which they will practice. Sub-specialties require the completion of a fellowship after residency.

Specialists in internal medicine

Specialty training is usually begun immediately following completion of entry-level training, or even before. In some jurisdictions, junior medical doctors must undertake generalist (un-streamed) training for one or more years before commencing specialization. Hence, depending on jurisdiction, a specialist physician (internist) often does not achieve recognition as a specialist until twelve or more years after commencing basic medical trainingâfive to eight years at university to obtain a basic medical qualification, and up to another nine years to become a specialist.

Regulation

In most jurisdictions, physicians (in either sense of the word) need government permission to practice. Such permission is intended to promote public safety, and often to protect the government spending, as medical care is commonly subsidized by national governments. All boards of certification now require that physicians demonstrate, by examination, continuing mastery of the core knowledge and skills for a chosen specialty. Re-certification varies by particular specialty between every seven and every ten years.

All medical practitioners

Among the English-speaking countries, this process is known either as licensure as in the United States, or as registration in the United Kingdom, other Commonwealth countries, and Ireland. Synonyms in use elsewhere include colegiaciĂłn in Spain, ishi menkyo in Japan, autorisasjon in Norway, Approbation in Germany, and ΏδξΚι ÎľĎγιĎÎŻÎąĎ in Greece. In France, Italy, and Portugal, civilian physicians must be members of the Order of Physicians to practice medicine.

In some countries, the profession largely regulates itself, with the government affirming the regulating body's authority. The best known example of this is probably the General Medical Council of Britain. In all countries, the regulating authorities will revoke permission to practice in cases of malpractice or serious misconduct.

In the large English-speaking federations (United States, Canada, Australia), the licensing or registration of medical practitioners is done at a state or provincial level. Australian states usually have a "Medical Board," which has now been replaced by the Australian Health Practitioner Regulatory Authority (AHPRA) in most states, while Canadian provinces usually have a "College of Physicians and Surgeons." All American states have an agency that is usually called the "Medical Board," although there are alternate names such as "Board of Medicine," "Board of Medical Examiners," "Board of Medical Licensure," "Board of Healing Arts," or some other variation.[14] After graduating from a first-professional school, physicians who wish to practice in the US usually take standardized exams, such as the USMLE.

Specialists in internal medicine

Most countries have some method of officially recognizing specialist qualifications in all branches of medicine, including internal medicine. Generally, the aim is to promote public safety by restricting the use of hazardous treatments. Other reasons for regulating specialists may include standardization of recognition for hospital employment and restriction on which practitioners are entitled to receive higher insurance payments for specialist services.

Performance and professionalism supervision

The issues of medical errors, drug abuse, and other issues in physician professional behavior have received significant attention across the world, in particular following a critical 2000 report which arguably launched the patient-safety movement.[15]

In the US, only the Department of Veterans Affairs randomly drug tests physicians, in contrast to drug testing practices for other professions that have a major impact on public welfare. Licensing boards at the US state level depend upon continuing education to maintain competence.[16] Through the utilization of the National Practitioner Data Bank, Federation of State Medical Boards' disciplinary report, and American Medical Association Physician Profile Service, the 67 State Medical Boards continually self-report any adverse/disciplinary actions taken against a licensed physician in order that the other Medical Boards in which the physician holds or is applying for a medical license will be properly notified and that corrective, reciprocal action can be taken against the offending physician.

In Europe, the health systems are governed according to various national laws, and can also vary according to regional differences.

Social role and world view

Biomedicine

Within Western culture and over recent centuries, medicine has become increasingly based on scientific reductionism and materialism. This style of medicine, which has been referred to as Western medicine, mainstream medicine, or conventional medicine, is now dominant throughout the industrialized world. Termed biomedicine by medical anthropologists,[17] it "formulates the human body and disease in a culturally distinctive pattern."[18] Within this tradition, the medical model is a term for the complete "set of procedures in which all doctors are trained."[19] A particularly clear expression of this world view, currently dominant among conventional physicians, is evidence-based medicine.

Within conventional medicine, most physicians still pay heed to their ancient traditions:

The critical sense and sceptical attitude of the citation of medicine from the shackles of priestcraft and of caste; secondly, the conception of medicine as an art based on accurate observation, and as a science, an integral part of the science of man and of nature; thirdly, the high moral ideals, expressed in that most "memorable of human documents" (Gomperz), the Hippocratic oath; and fourthly, the conception and realization of medicine as the profession of a cultivated gentleman.[20]

In this Western tradition, physicians are considered to be members of a learned profession, and enjoy high social status, often combined with expectations of a high and stable income and job security. However, medical practitioners often work long and inflexible hours, with shifts at unsociable times. Their high status is partly from their extensive training requirements, and also because of their occupation's special ethical and legal duties. Physicians are commonly members or fellows of professional organizations, such as the American College of Physicians or the Royal College of Physicians in the United Kingdom.

Alternative medicine

While contemporary biomedicine has distanced itself from its ancient roots in religion and magic, many forms of traditional medicine and alternative medicine continue to espouse vitalism in various guises: "As long as life had its own secret properties, it was possible to have sciences and medicines based on those properties."[21]

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines traditional medicine as "the sum total of the knowledge, skills, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness."[22] Practices known as traditional medicines include Ayurveda, Siddha medicine, Unani, ancient Iranian medicine, Irani, Islamic medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, traditional Korean medicine, acupuncture, Muti, IfĂĄ, and traditional African medicine.

In considering these alternate traditions that differ from biomedicine, medical anthropologists emphasize that all ways of thinking about health and disease have a significant cultural content, including conventional western medicine.[17][18]

Physicians' health

Some commentators have argued that physicians have duties to serve as role models for the general public in matters of health, for example by not smoking cigarettes.[23] Indeed, in most western nations relatively few physicians smoke, and their professional knowledge does appear to have a beneficial effect on their health and lifestyle.[24]

However, physicians do experience exposure to occupational hazards. Workplace stress is pervasive in the health care industry because of such factors as inadequate staffing levels, long work hours, exposure to infectious diseases and hazardous substances leading to illness or death, and in some countries threat of malpractice litigation. Other stressors include the emotional labor of caring for ill people and high patient loads. The consequences of this stress can include substance abuse, suicide, major depressive disorder, and anxiety, all of which occur at higher rates in health professionals than the general working population. Elevated levels of stress are also linked to high rates of burnout, absenteeism, diagnostic errors, and reduced rates of patient satisfaction.[25] In epidemic situations, such as the 2014-2016 West African Ebola virus epidemic, the 2003 SARS outbreak, and the COVID-19 pandemic, healthcare workers, including physicians, are at even greater risk, and are disproportionately affected in such outbreaks.

Shortage

As part of the worldwide shortage of health care professionals, many countries in the developing world have the problem of too few physicians. In 2013 the World Health Organization reported a 7.2 million shortage of doctors, midwives, nurses, and support workers worldwide. They estimated that by 2035 there would be a shortage of almost 12.9 million, which would serious implications for the health of billions of people across all regions of the world.[26] In 2015, the Association of American Medical Colleges warned that the US would face a doctor shortage of as many as 90,000 by 2025.[27]

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 Lesley Brown (ed.) The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles (Oxford University Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0198612711).

- â History of the School of Clinical Medicine University of Cambridge. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- â 3.0 3.1 Jeremy Butterfield (ed.), Fowler's Dictionary of Modern English Usage (Oxford University Press, 2015, ISBN 978-0199661350).

- â A. Ioli, J.C. Petithory, and J. ThĂŠodoridès, Francesco Redi and the Birth of Experimental Parasitology Hist Sci Med 31(1) (Apr-Jun 1997): 61-66. PubMed Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- â What is a physician? The Royal Australasian College of Physicians. Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- â Steve Pantilat, What Is a Hospitalist? The Hospitalist (2) (February, 2006). Retrieved May 13, 2020.

- â Choosing Between a Family Medicine Doctor and an Internal Medicine Doctor Beaumont Health. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- â The difference between family medicine and internal medicine Piedmont Hospital. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- â Fred Decker, Difference Between Internist & General Practitioner Houston Chronicle, August 9, 2018. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- â Internal Medicine vs. Family Medicine American College of Physicians. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- â What is a Podiatrist? APMA. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- â Geoffrey Lloyd (ed.), Hippocratic Writings (Penguin Classics, 1984, ISBN 978-0140444513).

- â Doctor of Osteopathic Medicine Medline Plus, April 9, 2020. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- â Contact a State Medical Board Federation of State Medical Boards. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- â Linda T. Kohn, Janet M. Corrigan, and Molla S. Donaldson (eds.), To Err is Human: Building A Safer Health System National Academy Press, 2000. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- â L.L. Leape and J.A. Fromson, Problem doctors: is there a system-level solution? Ann. Intern. Med. 144(2) (January 2006): 107â115. PubMed Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- â 17.0 17.1 Robert A. Hahn and Atwood D. Gaines (eds.), Physicians of Western Medicine: Anthropological Approaches to Theory and Practice (D. Reidel, 1985, ISBN 978-9027717900).

- â 18.0 18.1 Byron J. Good, Medicine, Rationality, and Experience: An Anthropological Perspective (Cambridge University Press, 1994, ISBN 978-0521425766).

- â R.D. Laing, The Politics of the Family (House of Anansi Press, 2011, ISBN 978-0887845468).

- â Sir William Osler, Chauvanism in Medicine: An address before the Canadian Medical Association, Montreal, September 17, 1902 (Williams & Wilkins, 1902).

- â Richard Grossinger, Planet Medicine: Origins (North Atlantic Books, 2001, ISBN 978-1556433696).

- â Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine World Health Organization. Retrieved April 13, 2020.

- â J.M. Appel, Smoke and mirrors: one case for ethical obligations of the physician as public role model Camb Q Healthc Ethics 18(1) (2009): 95â100. PubMed Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- â E. Frank, H. Biola, and C.A. Burnett, Mortality rates and causes among U.S. physicians Am J Prev Med 19(3) (2000): 155â159. PubMed Retrieved May 14, 2020.

- â Exposure to Stress: Occupational Hazards in Hospitals NIOSH Publication No. 2008â136, July 2008. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- â Global health workforce shortage to reach 12.9 million in coming decades World Health Organization, November 11, 2013. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- â Lenny Bernstein, U.S. faces 90,000 doctor shortage by 2025, medical school association warns The Washington Post, March 3, 2015. Retrieved May 14, 2020.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Lesley (ed.). The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary on Historical Principles. Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0198612711

- Butterfield, Jeremy (ed.). Fowler's Dictionary of Modern English Usage. Oxford University Press, 2015. ISBN 978-0199661350

- Good, Byron J. Medicine, Rationality, and Experience: An Anthropological Perspective. Cambridge University Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0521425766

- Grossinger, Richard. Planet Medicine: Origins. North Atlantic Books, 2001. ISBN 978-1556433696

- Hahn, Robert A., and Atwood D. Gaines (eds.). Physicians of Western Medicine: Anthropological Approaches to Theory and Practice. D. Reidel, 1985. ISBN 978-9027717900

- Laing, R.D. The Politics of the Family. House of Anansi Press, 2011. ISBN 978-0887845468

- Lloyd, Geoffrey (ed.). Hippocratic Writings. Penguin Classics, 1984. ISBN 978-0140444513

- Osler, Sir William. Chauvanism in Medicine: An address before the Canadian Medical Association, Montreal, September 17, 1902. Williams & Wilkins, 1902.

| Health science â Medicine |

|---|

| Anesthesiology | Dermatology | Emergency Medicine | General practice | Internal medicine | Neurology | Obstetrics & Gynaecology | Occupational Medicine | Pathology | Pediatrics | Physical Medicine & Rehabilitation | Podiatry | Psychiatry | Public Health | Radiology | Surgery |

| Branches of Internal medicine |

| Cardiology | Endocrinology | Gastroenterology | Hematology | Infectious diseases | Intensive care medicine | Nephrology | Oncology | Pulmonology | Rheumatology |

| Branches of Surgery |

| Cardiothoracic surgery | Dermatologic surgery | General surgery | Gynecological surgery | Neurosurgery | Ophthalmic surgery | Oral and maxillofacial surgery | Organ Transplantation | Orthopedic surgery | Otolaryngology (ENT) | Pediatric surgery | Plastic surgery | Podiatric surgery | Surgical oncology | Trauma surgery | Urology | Vascular surgery |

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.