| Books of the |

Leviticus is the third book of the Hebrew Bible. The English name is derived from the Latin Liber Leviticus and the Greek (το) Λευιτικόν. In Jewish writings it is customary to cite the book by its first word, Vayikra, "and He called." The book is mainly concerned with religious regulations, priestly ritual, and criminal law. It consists of two large sections, identified by scholars as the Priestly Code and the Holiness Code. Both of these are presented as being dictated by God to Moses while the Israelites were encamped at Mount Sinai. Despite the English title of the work, it is important to note that the book makes a strong distinction between the priesthood, who are identified as being descended from Aaron, and mere Levites, with whom it is less concerned.

Observant Jews still follow the laws contained in Leviticus, except for those that can no longer be observed because of the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem as the only authorized place of sacrifice (see Deuteronomy). Christians generally consider much of Leviticus to be non-binding on them as members of the New Covenant initiated by Jesus. However, many of the moral and civil laws contained in Leviticus have become permanent parts of the Christian-based western ethical and legal tradition.

Leviticus is a source of two of the Bible's most famous sayings. One is often used as a negative summary of ancient Jewish tradition: "eye for eye, tooth for tooth." (Lev. 24:20) The other, ironically, is a saying popularized by Jesus and often thought of as the opposite of Old Testament law: "Love your neighbor as yourself" (Lev. 19:18).

Summary

In contrast to the other books of the Pentateuch, Leviticus contains very little in the way of narrating the story of the Israelites. The book is generally considered to consist of two large sections, both of which contain a number mitzvot, or commandments. The second part, Leviticus 17-26, is known as the Holiness Code. It places particular emphasis on holiness and that which is considered sacred. Although Exodus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy also deal with religious regulations, Leviticus focuses almost entirely on this subject and thus constitutes a major source of Jewish law.

The priestly code

The first part of Leviticus (chapters 1-16), together with Leviticus 27, constitutes the main portion of what scholars call the Priestly Code, which describes the details of rituals, and of worship, as well as details of ritual cleanliness and uncleanliness. It emphasizes the role of the Aaronic priesthood, comprised of "Aaron and his sons."[1] Within this section are laws concerning:

Laws on sacrifice

- Burnt offerings, grain offerings, and fellowship (peace) offerings (1-3). Burnt offerings are distinguished from fellowship offerings in that fellowship offerings are "for food," and may involve female animals as well as male ones. Priests need only sacrifice a handful of any grain offering, keeping the rest for their own consumption.

- Sin (guilt) offerings, and trespass offerings (4-5). Sin offerings are made for those who unintentionally violate a commandment. Penalties are also specified for such acts as failing to offer testimony in a public law case, touching ceremonially unclean objects, and careless oath-taking. Trespass offenses include entering forbidden areas, as well as touching or harming sacred objects. For crimes of theft and fraud, both a sin offering and restitution must be made, the latter consisting of the full value of any lost property plus an additional one fifth of its worth.

- Priestly duties and rights concerning the offering of sacrifices (6-7). Priests are not to consume any part of the burnt offering. They may consume all but a handful of grain offerings, and are allowed to consume certain portions of sin offerings within the Tabernacle confines.

Narrative concerning Aaron and his sons

In Leviticus 8, Aaron and his sons are formally ordained. Moses ceremonially washes and dresses them, and then anoints Aaron as the high priest. After conducting a former guilt offering of a bull and a burnt offering of a ram, Moses anoints Aaron with sacrificial blood and then consecrates Aaron's sons by sprinkling them with blood and anointing oil. After this, Aaron and his sons eat a sacramental meal and remain in the the sacred tent for seven days.

On the eighth day, Aaron assumes his duties as high priest, carefully conducting various offerings. God signals his approval of Aaron's work by sending fire from heaven to consume the sacrifices he has offered (Lev. 9:24). However, when Aaron's sons Nadab and Abihu use "unauthorized fire" in attending the altar, they are immediately slain by God for this sin (Lev. 10:1). Aaron and his descendants are forbidden to tear their priestly garments during the mourning process.

Although conveyed in narrative fashion, the story of the consecration of Aaron and his sons also represents a detailed manual for the formal investiture of priests throughout the period of the Tabernacle and later Temple of Jerusalem. Although two of his sons sin and are immediately punished with death, in Leviticus, Aaron commits no sin as he does in Exodus in the episode of the Golden Calf and Numbers in the incident of him and Miriam criticizing Moses' marriage.

Purity and impurity

- Laws about clean and unclean animals (11). Land animals must chew their cud and also have cloven hooves. Sea creatures must have both fins and scales. Bats and specific types of meat-eating birds are forbidden. Among the insects, only certain kinds of locusts and grasshoppers are permitted.

- Laws concerning childbirth (12). Circumcision of males is commanded on the eighth day after birth. Women are "unclean" for 33 days after the birth of a male, and 66 days after the birth of a female. After this time, the mother must also offer year-old lamb as a burnt offering and a young pigeon or a dove as a sin offering.

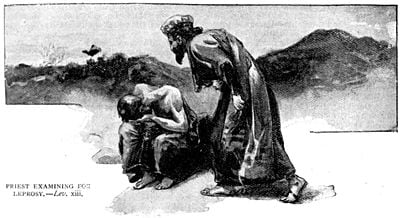

- Detailed laws concerning skin diseases, as well as mildew on clothes and houses (13-14).

- Laws concerning bodily discharges such as puss and menstrual blood which render both a person and his/her clothes "unclean" (15).

- Laws instituting a day of national atonement, Yom Kippur. Also included are various prohibitions against entering the inner sanctuary of the Tabernacle and the tradition of sending the scapegoat into the wilderness (16).

The Holiness Code

- Laws concerning idolatry, the slaughter of animals, dead animals, and the consumption of blood (17).

Chapter 18:3-45 contains an address of God to the Israelites, setting forth the blessing that will flow from obedience and the curses that will result from rebellion to the Law. The speech closely resembles Deuteronomy 28 and often cited as evidence of the separate character of the Holiness Code. This section places particular emphasis on holiness, and the idea of the sacred versus the profane. The laws are less clearly categorized as in earlier chapters. Within this section are:

- Laws concerning sexual conduct such as incest, adultery, male homosexuality, and sex during menstruation. Also prohibited is sacrificing one's child to the god Moloch (18).

- A set of decrees similar to the Ten Commandments: honor one's father and mother, observe the sabbath, do not worship idols or other gods, make fellowship offerings acceptably, the law of gleaning, injunctions against lying and stealing, and against swearing falsely or taking God's name in vain. Laws are instituted against mistreating the deaf, the blind, the elderly, and the poor, against the poisoning of wells, and against hating one's brother. sex with female slaves is regulated, as are harming oneself, shaving, prostitution, and the observance of Sabbaths. The famous command is given to forbear grudges and to "Love your neighbor as yourself." Sorcery and mediumship are banned. Resident aliens are not to be mistreated, and only honest weights and measures are to be used (19).

- The death penalty is instituted for both Israelites and foreigners who sacrifice their children to Moloch, and also for people who consult sorcerers and mediums, those who curse their own parents, or commit certain categories of sexual misconduct. The punishment for having sex with a menstruating woman is that both parties are to be "cut off from the people" (20).

- Laws concerning priestly conduct, and prohibitions against the disabled, ill, and blemished, from becoming priests. Laws against presenting blemished sacrifices (21-22).

- Laws concerning the observation of the several annual feasts and the sabbath (23).

- Laws concerning the altar of incense (24:1-9).

- The narrative case law of a blasphemer being stoned to death. The death penalty is specified for murder cases. For cases of physical injury, the law is to be "fracture for fracture, eye for eye, tooth for tooth." Foreigners are not to be given different punishments from Israelites (24:10-23).

- Laws concerning the sabbath and jubilee years, the rights of Levites, real estate law, and laws governing slavery and redemption (25).

- Finally, a hortatory conclusion to the section, giving promises of blessing for obedience to these commandments, and dire warnings for those that might disobey them (26:22).

Although it comes at the end of the book, Leviticus 27 is regarded by many scholars as originally part of the Priestly Code. In its present form it appears as an appendix to the just-concluded Holiness Code. In addition to regulations concerning the proper discharging of religious vows, it contains an injunction that one-tenth of one's cattle and crops belong to God.

Jewish and Christian views

Orthodox Jews believe that this entire book is the word of God, dictated by God to Moses on Mount Sinai. In Talmudic literature, there is evidence that Leviticus was the first book of the Bible taught in the early rabbinic system. Although the sacrifices decreed in Leviticus were suspended after the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem in 70 C.E., other Levitical laws are considered still valid. Indeed, rabbinical tradition in some ways goes beyond these laws. Talmudic debates often centered on how exactly to interpret and apply the various regulations of Leviticus and other books of the Torah.

Reform and secular Jews generally take the view that the Levitical laws are no longer binding for the most part.

Christians believe that Leviticus is the word of God, but generally hold that most of the non-ethical laws of the Hebrew Bible become obsolete as a result of the New Covenant initiated by Jesus. Sacrifices became unnecessary because Jesus himself brings atonement to believers through his death and resurrection.[2] Saint Paul's letters deal in detail with the need for Christians to realize that only faith in Jesus, and not obedience to the Jewish laws, brings salvation.

As far as the dietary laws are concerned, some cite 1 Corinthians 10:23-26—in which Paul directs followers to "eat anything sold in the meat market without raising questions of conscience"—as exempting them from following the dietary laws set forth in Leviticus.[3] In addition, in Acts 10, God directs Saint Peter to "kill and eat" ritually unclean animals, declaring, "Do not call anything impure that God has made clean."

Critical views

The sources

According to the documentary hypothesis, much of Leviticus is identified as originating from the priestly source, "P," which also runs through parts of several other books of the Torah. Strongly supportive of the Aaronic priesthood, Leviticus is nevertheless said to consist of several layers of accretion from earlier collections of laws. The Holiness Code is regarded as an independent document later combined with other sections into Leviticus as we have it today.

The priestly source is envisioned as a rival version of the stories contained within JE, which in turn is a combination of two earlier sources, J and E. P is more concerned with religious law and ritual than either J or E. It is also generally more uplifting of the role of Aaron, while E—thought by some to have originated from the non-Aaronic priesthood at Shiloh—is overtly critical of Aaron. The Holiness Code is seen as being the law code that the priestly source presented as being dictated to Moses at Sinai, in place of the Covenant Code preserved in Exodus. On top of this, over time, different writers, of varying levels of narrative competence, ranging from repetitive tedium to case law, inserted various laws, some from earlier independent collections.

Structure

Chiastic structure is a literary structure used most notably in the Torah. The term is derived from the letter Chi, a Greek letter that is shaped like an X. The structure in Exodus/Leviticus comprises concepts or ideas in an order ABC…CBA so that the first concept that comes up is also the last, the second is the second to last, and so on.

The ABC…CBA chiastic structure is used in many places in the Torah, including Leviticus. This kind of chiastic structure is used to give emphasis to the central concept—"C." A notable example is the chiastic structure running from the middle of the Book of Exodus through the end of the Book of Leviticus. The structure begins with the covenant made between God and the Jewish People at Mount Sinai and ends with the admonition from God to the Jews if they will not keep this agreement. The main ideas are in the middle of Leviticus, from chapter 11 through chapter 20. Those chapters deal with the holiness of the Tabernacle and the holiness of the Jewish homeland in general.

The chiastic structure points the reader to the central idea: holiness. The idea behind the structure is that if the Jews keep the covenant and all the laws around the central concept, they will be blessed with a sense of holiness in their Tabernacle and in their land in general.

Notes

- ↑ The Book of Deuteronomy specifies that not only descendants of Aaron, but any Levite who moves from the outlying areas to the capital should be recognized as an authorized priest, leading modern scholars to the belief that Deuteronomy is a later work, reflecting the centralizing reforms of the seventh century B.C.E.

- ↑ Catholic and Orthodox traditions include the sacraments of confession, absolution, and penance to deal with sins committed after baptism.

- ↑ Paul's standard here seems to be contradicted by the policy for gentile Christians indicated in Acts 15:20: "...abstain from food polluted by idols... from the meat of strangled animals and from blood." Markets in major cities of the Roman Empire often sold meat ritually slaughtered by pagan priests.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Carmy, Shalom (ed.). Modern Scholarship in the Study of Torah: Contributions and Limitations. Jason Aronson, 1996. ISBN 978-1568214504

- Cross, Frank Moore. Canaanite Myth and Hebrew Epic. Harvard University Press, 1973. ISBN 0674091760

- Dever, William G. What Did the Biblical Writers Know and When Did They Know It?: What Archaeology Can Tell Us About the Reality of Ancient Israel. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2002. ISBN 978-0802821263

- Douglas, Mary. Leviticus As Literature. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0199244195

- Finkelstein, Israel. The Bible Unearthed: Archeology's New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Free Press, 2002. ISBN 0684869136

- Friedman, Richard E. Who Wrote the Bible?. Harper, SanFrancisco, 1997 ISBN 978-0060630355

- Kaufmann, Yehezkel, and Moishe Greenberg (trans.). The Religion of Israel, from Its Beginnings to the Babylonian Exile. University of Chicago Press, 1960. ISBN 978-0226427287

- Mendenhall, George E. Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction to the Bible in Context. Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0664223133

- Milgrom, Jacob. Leviticus: A Book of Ritual and Ethics. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2004. ISBN 978-0800695149

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2023.

- Translation with Rashi's commentary – www.Chabad.org.

- Several Christian translations – www.biblegateway.com..

- Book of Leviticus – www.Jewish Encyclopedia.com.

- The Literary Structure of Leviticus – chaver.com.

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.