Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments, also known as the Decalogue ("Ten Statements"),[1] are a list of religious and moral laws, which, according to biblical tradition, were given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai in two stone tablets.[2] Upon these tablets were listed ten ethical precepts that are listed in two separate biblical passages (Exodus 20:2-17 and Deuteronomy 5:6-21).

These commandments feature prominently in Judaism and Christianity. They also provide the foundation for many modern secular legal systems and codes. Many other religions such as Buddhism, Hinduism, and Jainism have comparable laws or principles.

Origins

According to the Hebrew Bible, Moses was called by God to receive the Ten Commandments on Mount Sinai, and to share them with the people of Israel in the third month after their Exodus from Egypt:

- "God said to Moses, 'Come up to Me, to the mountain, and remain there. I will give you the stone tablets, the Torah and the commandment that I have written for [the people's] instruction.'" (Exodus 24:12)

Initially, the commandments were said to have been written by God himself and then given to Moses; however, the Bible reports that when Moses saw that the Hebrews had gone astray, he broke the tablets in disgust. Thereafter, God commanded Moses to rewrite the Ten Commandments himself and to carve two new tablets like the broken originals.[3] This second set, brought down from Mount Sinai (Exodus 34:29), was then placed in the Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 25:16, Exodus 25:21, Exodus 40:20).

Biblical scholars, however, suggest that the extant list of the Ten Commandments likely became authoritative only relatively late in the history of the Hebrew people rather than during the time of Moses. Textual evidence suggests that early Israelite religion did not always have had an injunction against graven images or worshiping other gods, and these injunctions came into force only after the Yawheh-only faction of the priesthood took power during the second half of the period of the Divided Kingdoms (c. 922-722 B.C.E.). There is evidence to indicate that the Yahweh-only ideology did not come to the fore among the Israelites until well into the period of Kings, and it was not until after the Babylonian exile that monotheism took firm root among the Jews. Yahweh himself was sometimes worshiped in a way that later generations would consider idolatrous. For example, the presence of golden cherubim and cast bronze bull statues at the Temple of Jerusalem has lead many scholars to question whether the Second Commandment against graven images could have been in effect at this time, rather than being the creation of a later age written back into history by the biblical authors.

From another perspective, it is also possible that the Ten Commandments may have originated from Hebrew exposure to ancient Egyptian practices.[4] For instance, Chapter 125 of the Egyptian Book of the Dead (the Papyrus of Ani) includes a list of commandments in order to enter the afterlife. These sworn statements bear a remarkable resemblance to the Ten Commandments in their nature and their phrasing. For example, they include the phrases "not have I defiled the wife of man," "not have I committed murder," "not have I committed theft," "not have I lied," "not have I cursed god," "not have I borne false witness," and "not have I abandoned my parents." The Hebrews may have assimilated these Egyptian laws after their Exodus from Egypt, albeit the Book of the Dead has additional requirements, and, of course, does not require worship of YHWH.

Comparative Texts of the Ten Commandments

The biblical lists of the Ten commandments are found in two primary chapters (Exodus 20:2-27 and Deut. 5: 6-21). These lists are very similar to each other but contain slight variations. A comparision of their lists is provided below:

| Exodus 20:2-17 | Deuteronomy 5:6-21 |

|---|---|

| 2 I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery;

3 you shall have no other gods before me. 4 You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. 5 You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I the Lord your God am a jealous God, punishing children for the iniquity of parents, to the third and the fourth generation of those who reject me, 6 but showing steadfast love to the thousandth generation of those who love me and keep my commandments. 7 You shall not make wrongful use of the name of the Lord your God, for the Lord will not acquit anyone who misuses his name. 8 Remember the Sabbath day, and keep it holy. 9 For six days you shall labour and do all your work. 10 But the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God; you shall not do any workâyou, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your livestock, or the alien resident in your towns. 11 For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the Sabbath day and consecrated it. 12 Honour your father and your mother, so that your days may be long in the land that the Lord your God is giving you. 13 You shall not murder.[5] 14 You shall not commit adultery. 15 You shall not steal. [Jewish versions translate word as "kidnap"] 16 You shall not bear false witness against your neighbour. 17 You shall not covet your neighbourâs house; you shall not covet your neighbourâs wife, or male or female slave, or ox, or ass, or anything that belongs to your neighbour. |

6 I am the Lord your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery;

7 you shall have no other gods before me. 8 You shall not make for yourself an idol, whether in the form of anything that is in heaven above, or that is on the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. 9 You shall not bow down to them or worship them; for I the Lord your God am a jealous God, punishing children for the iniquity of parents, to the third and fourth generation of those who reject me, 10 but showing steadfast love to the thousandth generation of those who love me and keep my commandments. 11 You shall not make wrongful use of the name of the Lord your God, for the Lord will not acquit anyone who misuses his name. 12 Observe the sabbath day and keep it holy, as the Lord your God commanded you. 13 For six days you shall labour and do all your work. 14 But the seventh day is a Sabbath to the Lord your God; you shall not do any workâyou, or your son or your daughter, or your male or female slave, or your ox or your donkey, or any of your livestock, or the resident alien in your towns, so that your male and female slave may rest as well as you. 15 Remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the Lord your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm; therefore the Lord your God commanded you to keep the sabbath day. 16 Honour your father and your mother, as the Lord your God commanded you, so that your days may be long and that it may go well with you in the land that the Lord your God is giving you. 17 You shall not murder. 18 Neither shall you commit adultery. 19 Neither shall you steal. [Jewish versions translate word as "kidnap"] 20 Neither shall you bear false witness against your neighbour. 21 Neither shall you desire your neighbourâs wife. Neither shall you desire your neighbourâs house, or field, or male or female slave, or ox, or donkey, or anything that belongs to your neighbour. |

Division of the Commandments

Religious groups have divided the commandments in different ways. For instance, the initial reference to Egyptian bondage is important enough to Jews that it forms a separate commandment. Catholics and Lutherans see the first six verses as part of the same command prohibiting the worship of pagan gods, while Protestants (except Lutherans) separate all six verses into two different commands (one being "no other gods" and the other being "no graven images"). Catholics and Lutherans separate the two kinds of coveting (namely, of goods and of the flesh), while Protestants (but not Lutherans) and Jews group them together. According to the Medieval Sefer ha-Chinuch, the first four statements concern the relationship between God and human beings, while the second six statements concern the relationship between human beings.

The passage in Exodus contains more than ten imperative statements, totalling 14 or 15 in all. However, the Bible itself assigns the count of "10", using the Hebrew phrase Ęťaseret had'varimâtranslated as the 10 words, statements or things.[6] Various religions divide the commandments differently. The table below highlights those differences.

| Commandment | Jewish | Orthodox | Roman Catholic, Lutheran* | Anglican, Reformed, and Other Protestant |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I am the Lord thy God | 1 | 1 | 1 | - |

| Thou shalt have no other gods before me | 2 | 1 | ||

| Thou shalt not make for thyself an idol | 2 | 2 | ||

| Thou shalt not make wrongful use of the name of thy God | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 |

| Remember the Sabbath and keep it holy | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 |

| Honor thy Mother and Father | 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 |

| Thou shalt not murder | 6 | 6 | 5 | 6 |

| Thou shalt not commit adultery | 7 | 7 | 6 | 7 |

| Thou shalt not steal | 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 |

| Thou shalt not bear false witness | 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's wife | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 |

| Thou shalt not covet thy neighbor's house. | 10 |

Interpretations

Jewish understanding

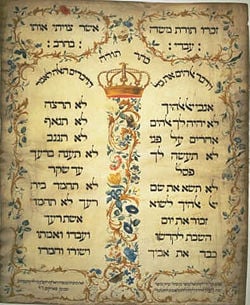

In Biblical Hebrew, the Ten Commandmenrs are termed ע׊רת ×××ר×× (translit. Aseret ha-DvarĂŽm), and in Rabbinical Hebrew they are known as ע׊רת ×××ר×ת (translit. Aseret ha-Dibrot). Both of these Hebrew terms mean "the ten statements." Traditional Jewish sources (Mekhilta de Rabbi Ishmael, de-ba-Hodesh 5) discuss the placement of the ten commandments on two tablets. According to Rabbi Hanina ben Gamaliel, five commandments were engraved on the first tablet and five on the other, whereas the Sages contended that ten were written on each. While most Jewish and Christian depictions follow the first understanding, modern scholarship favours the latter, comparing it to treaty rite in the Ancient Near East, in the sense of tablets of covenant. Diplomatic treaties, such as that between Egyptian Pharaoh Ramses II and the Hittite King Hattusilis III, circa 1270 B.C.E., were duplicated on stone with a copy for each party, and the subordinate party would place their copy of the pact in the main temple to his god, in oath to the king (cf. Ezekiel 17:11-19). In a pact between a nation and its God, then, the Israelites placed both copies in their temple.[7]

Exodus 32:15 records that the tablets "were written on both their sides." The Talmud (tractate Shabbat 104a) explains that there were miracles involved with the carving on the tablets. One was that the carving went the full thickness of the tablets. There is a letter in the Hebrew alphabet called a samech that looks similar to the letter "O" in the English alphabet. The stone in the center part of the letter should have fallen out, as it was not connected to the rest of the tablet, but it did not; it miraculously remained in place. Secondly, the writing was miraculously legible from both the front and the back, even though logic would dictate that something carved through and through would show the writing in mirror image on the back.

According the Jewish understandings, the Torah includes 613 commandments, of which those listed in the decalogue count only for ten. Most Jewish authorities thus do not automatically ascribe to these ten commandments any greater significance, or any special status, as compared to the remainder of the canon of Jewish law. Indeed, when undue emphasis was being placed on them, daily communal recitation of them was discontinued (Talmud, tractate Berachot 12a). The Jewish tradition does, however, recognize these "ten commandments" as the ideological basis for the rest of the commandments; a number of works (starting with Rabbi Saadia Gaon) have made groupings of the commandments according to their links with the Ten Commandments.

Traditional Jewish belief is that these commandments, among the 613, apply solely to the Jewish people, and that the laws incumbent on the rest of humanity are outlined in the seven Noahide Laws. In the era of the Sanhedrin, transgressing any one of the ten commandments theoretically carried the death penalty; though this was rarely enforced due to a large number of stringent evidentiary requirements imposed by the oral law.

According to Jewish exegesis, the commandment "This shall not murder" should not be understood as "Thou shall not kill." The Hebrew word ratsach, used in this commandment, is close to the word murder but it does not translate directly to the word murder; however, kill is a clear mistranslation. Some Jews take offense at translations which state "Thou shall not kill," which they hold to be a flawed interpretation, for there are circumstances in which one is required to kill, such as if killing is the only way to prevent one person from murdering another, or killing in self-defense. While most uses of the word "ratsach" are in passages describing murder, in Proverbs 22:13 a lion ratsach a man to death. Since a lion cannot murder anyone, murder is a flawed translation as well. In Joshua 20:3, ratsach is used to describe death by negligence. A closer translation therefore would be to kill in the manner of a predatory animal.

Samaritan understanding

The Samaritan Pentateuch varies in the ten commandments' passages.[8] Their Deuteronomical version of the passage is much closer to that in Exodus, and in their division of the commandments allows a tenth commandment on the sanctity of Mount Gerizim may be included. The Samaritan tenth commandment is even present in the Septuagint, though Origen notes that it is not part of the Jewish text.

The text of the commandment follows:

- And it shall come to pass when the Lord thy God will bring thee into the land of the Canaanites whither thou goest to take possession of it, thou shalt erect unto thee large stones, and thou shalt cover them with lime, and thou shalt write upon the stones all the words of this Law, and it shall come to pass when ye cross the Jordan, ye shall erect these stones which I command thee upon Mount Gerizim, and thou shalt build there an altar unto the Lord thy God, an altar of stones, and thou shalt not lift upon them iron, of perfect stones shalt thou build tine altar, and thou shalt bring upon it burnt offerings to the Lord thy God, and thou shalt sacrifice peace offerings, and thou shalt eat there and rejoice before the Lord thy God. That mountain is on the other side of the Jordan at the end of the road towards the going down of the sun in the land of the Canaanites who dwell in the Arabah facing Gilgal close by Elon Moreh facing Shechem.[9]

Christian understandings

Jesus refers to the commandments, but condenses them into two general commands: love God (Shema) and love other people (Matthew 22:34-40). Nevertheless, various Christian understandings of the Ten commandments have developed in different branches of Christianity.

The text of what Catholics recognize as the first commandment precedes and follows the "no graven images" warning with a prohibition against worshipping false gods. Some Protestants have claimed that the Catholic version of the ten commandments intentionally conceals the biblical prohibition of idolatry. However, the Bible includes numerous references to carved images of angels, trees, and animals (Exodus 25:18-21; Numbers 21:8-9; 1 Kings 6:23-28; 1Kings 6:29; Ezekiel 41: 17-25) that were associated with worship of God. Catholics and Protestants alike erect nativity scenes or use images to aid their Sunday-school instruction. (While not all Catholics have a particularly strong devotion to icons or other religious artifacts, Catholic teaching distinguishes between veneration (dulia) â which is paying honor to God through contemplation of objects such as paintings and statues, and adoration (latria) â which is properly given to God alone.) Catholics confess one God in three persons and bow and serve no god but the Father, Son and Holy Spirit. Catholics also point to the Second Council of Nicaea (the 7th Ecumenical Council) which settled the Iconoclasm controversy that was brought on by the Muslim idea of shirk and the occupation of Constantinople (New Rome) under the Ottoman Empire and the Muslims.

Catholic and Orthodox Christians do not refrain from work on Saturday. However, they do refrain from work on Sunday. Furthermore, the Catholic Church states in the Catechism (2185) that, "On Sundays and other holy days of obligation, the faithful are to refrain from engaging in work or activities that hinder the worship owed to by God, the joy proper to the Lord's Day, the performance of the works of mercy, and the appropriate relaxation of mind and body." Necessary work is permitted however, and the Catechism goes on to state that, "Family needs or important social service can legitimately excuse from the obligation of Sunday rest." As well, the Bible, in Mark 2:23-28, states that, "The Sabbath was made for man, and not man for the Sabbath." Some Protestant Christians, such as Seventh-day Adventists, observe the Sabbath day and hence refrain from work on Saturday. Other Protestants observe Sunday as a day of rest.

For many Christians, the Commandments are also seen as general "subject headings" for moral theology, in addition to being specific commandments in themselves. Thus, the commandment to honor father and mother is seen as a heading for a general rule to respect legitimate authority, including the authority of the state. The commandment not to commit adultery is traditionally taken to be a heading for a general rule to be sexually pure, the specific content of the purity depending, of course, on whether one is married or not.

Protestant Views

There are many different denominations of Protestantism, and it is impossible to generalise in a way that covers them all. However, this diversity arose historically from fewer sources, the various teachings of which can be summarized, in general terms.

Lutherans, Reformed, Anglicans, and Anabaptists all taught, and their descendants still predominantly teach, that the ten commandments have both an explicitly negative content, and an implied positive content. Besides those things that ought not to be done, there are things which ought not to be left undone. So that, besides not transgressing the prohibitions, the faithful abiding by the commands of God includes keeping the obligations of love. The ethic contained in the Ten Commandments and indeed in all of Scripture is, "Love the Lord your God with all of your heart, and mind, and soul, and strength, and love your neighbor as yourself," and the Golden Rule, "Do unto others as you would have them do unto you."

Lutherans, especially, influentially theorized that there is an antithesis between these two sides of the word of God, the positive and the negative. Love and gratitude is a guide to those under the Gospel, and the prohibitions are for unbelievers and profane people. This antithesis between Gospel and Law runs through every ethical command, according to the Lutheran understanding.

The Anabaptists have held that the commandments of God are the content of the covenant established through Christ: faith is faithfulness, and thus, belief is essentially the same thing as obedience.

Reformed and Anglicans have taught the abiding validity of the commandments, and call it a summation of the "moral law," binding on all people. However, they emphasize the union of the believer with Christ - so that the will and power to perform the commandments does not arise from the commandment itself, but from the gift of the Holy Spirit. Apart from this grace, the commandment is only productive of condemnation, according to this family of doctrines.

Modern Evangelicalism, under the influence of dispensationalism, commonly denies that the commandments have any abiding validity as a requirement binding upon Christians; however, they contain principles which are beneficial to the believer. Dispensationalism is particularly emphatic about the dangers of legalism, and thus, in a distinctive way de-emphasises the teaching of the law (see antinomianism). Somewhat analogously, Pentecostalism and the Charismatic movement typically emphasizes the guidance of the Holy Spirit, and the freedom of the Christian from outward commandments, sometimes in antithesis to the letter of the Law. Quakers and pietism have historically set themselves against the Law as a form of commandment binding on Christians, and have emphasized the inner guidance and liberty of the believer, so that the law is fulfilled not merely by avoiding what the Law prohibits, but by carrying out what the Spirit of God urges upon their conscience.

Muslim understanding

Muslims regard Moses as one of their greatest prophets, but they reject the biblical versions of the Ten Commandments. Islam teaches that the Biblical text used in Judaism and Christianity has been corrupted over the years, by carelessness or malice, from its divine original. Muslims believe that the Qur'an is a revelation from God intended to restore the original Adamic and Abrahamic faith.

Despite the Ten Commandments not being explicitly mentioned in the Qur'an, they are implied by the following verses in the Quran:

- "There is no other god beside God."(47:19)

- "My Lord, make this a peaceful land, and protect me and my children from worshiping idols." (14:35)

- "Do not subject God's name to your casual swearing, that you may appear righteous, pious, or to attain credibility among the people." (2:224)

- "O you who believe, when the Congregational Prayer (Salat Al-Jumu`ah) is announced on Friday, you shall hasten to the commemoration of GOD, and drop all business." (62:9)

The Sabbath was relinquished with the revelation of the Quran. Muslims are told in the Quran that the Sabbath was only decreed for the Jews. (16:124) God, however, ordered Muslims to make every effort and drop all businesses to attend the congregational (Friday) prayer. The Submitters may tend to their business during the rest of the day. - "....and your parents shall be honored. As long as one or both of them live, you shall never say to them, "Uff" (the slightest gesture of annoyance), nor shall you shout at them; you shall treat them amicably." (17:23)

- "....anyone who murders any person who had not committed murder or horrendous crimes, it shall be as if he murdered all the people." (5:32)

- "You shall not commit adultery; it is a gross sin, and an evil behavior." (17:32)

- "The thief, male or female, you shall mark their hands as a punishment for their crime, and to serve as an example from God. God is Almighty, Most Wise." (5:38 - 39)

- "Do not withhold any testimony by concealing what you had witnessed. Anyone who withholds a testimony is sinful at heart." (2:283)

- "And do not covet what we bestowed upon any other people. Such are temporary ornaments of this life, whereby we put them to the test. What your Lord provides for you is far better, and everlasting." (20:131)

Controversies

Sabbath day

Most Christians believe that Sunday is a special day of worship and rest, commemorating the Resurrection of Jesus on the first day of the week on the Jewish calendar. Most Christian traditions teach that there is an analogy between the obligation of the Christian day of worship and the Sabbath-day ordinance, but that they are not literally identical. For many Christians, the Sabbath ordinance has not so much been removed as superseded by a "new creation" (2 Corinthians 5:17). For this reason, the obligation to keep the Sabbath is not the same for Christians as in Judaism.

Still others believe that the Sabbath remains as a day of rest on the Saturday, reserving Sunday as a day of worship. In reference to Acts 20:7, the disciples came together on the first day of the week (Sunday) to break bread and to hear the preaching of the apostle Paul. This is not the first occurrence of Christians assembling on a Sunday; Jesus appeared to the Christians on the "first day of the week" while they were in hiding. One can maintain this argument in that Jesus himself maintained the Sabbath, although not within the restrictions that were mandated by Jewish traditions; the Pharisees often tried Jesus by asking him if certain tasks were acceptable according to the Law (see: Luke 14:5). This would seem to indicate that while the Sabbath was still of vital important to the Jews, Sunday was a separate day for worship and teaching from Scriptures.

Sabbatarian Christians (such as Seventh-day Adventists) disagree with the common Christian view. They argue that the custom of meeting for worship on Sunday originated in paganism, specifically Sol Invictus, and constitutes an explicit rejection of the commandment to keep the seventh day holy. Instead, they keep Saturday as the Sabbath, believing that God gave this command as a perpetual ordinance based on his work of creation. Sabbatarians claim that the seventh day Sabbath was kept by all Christian groups until the 2nd and 3rd century, by most until the 4th and 5th century, and a few thereafter, but because of opposition to Judaism after the Jewish-Roman wars, the original custom was gradually replaced by Sunday as the day of worship. They often teach that this history has been lost, because of supression of the facts by a conspiracy of the pagans of the Roman Empire and the clergy of the Catholic Church.

You shall not steal

Significant voices of academic theologians (such as German Old Testament scholar A. Alt: Das Verbot des Diebstahls im Dekalog (1953) suggest that commandment "You shall not steal." was originally intended against stealing people - against abductions and slavery, in agreeance with the Jewish interpretation of the statement as "you shall not kidnap." With this understanding the second half of the ten commandments proceeds from protection of life, through protection of heredity, to protection of freedom, protection of law, and finally protection of property. As interesting as it may be, this suggestion has not gained wider acceptance.

Idolatry

Christianity holds that the essential element of the commandment prohibiting "any graven image, or any likeness of any thing that is in heaven above" is "and bow down and worship it." Thus, they hold that one may build and use "likenesses," as long as the object is not worshipped. As a result, many Christian buildings and services feature images, some feature statues, and in some Orthodox services, icons are venerated. For most Christians, this practice is understood as fulfilling the observance of this commandment, as the images are not being worshipped.

Eastern Orthodoxy teaches that the incarnation of God as a human, Jesus, makes it permissible and necessary to venerate icons.

For Jews and Muslims (and some Protestants as well), veneration seems to violate this commandment. Jews and Muslims read this commandment as prohibiting the use of idols and images in any way.

Very few Christians oppose the making of any images at all, but some groups have been critical of the use others make of images in worship (See iconoclasm). In particular, the Orthodox have criticized the Roman Catholic use of decorative statues, Roman Catholics have criticized the Orthodox veneration of icons, and some Protestant groups have criticized the use of stained-glass windows by many other denominations. Jehovah's Witnesses criticize the use of all of the above, as well as the use of the cross. Amish people forbid any sort of graven image, such as photos.

Public monuments and controversy in the USA

There is an ongoing dispute in the United States concerning the posting of the Ten Commandments on public property. Certain conservative religious groups, alarmed by the banning of officially-sanctioned prayer from public schools by the U.S. Supreme Court, have sought to protect their right to express their religious beliefs in public life. As a result they have successfully lobbied many state and local governments to display the ten commandments in public buildings. As seen above, any attempt to post the Decalogue on a public building necessarily takes a sectarian stance; Protestants and Roman Catholics number the commandments differently. Hundreds of these monuments â including some of those causing dispute â were originally placed by director Cecil B. DeMille as a publicity stunt to promote his 1956 film The Ten Commandments.[10]

Secularists and most liberals oppose the posting of the Ten Commandments on public property, arguing that it is violating the separation of church and state. Conservative groups claim that the commandments are not necessarily religious, but represent the moral and legal foundation of society. Secularist groups counter that they are explicitly religious, and that statements of monotheism like "Thou shalt have no other gods before me" are unacceptable to many religious viewpoints, such as atheists or followers of polytheistic religions. In addition, if the Commandments were posted, it would also require members of all religions to likewise be allowed to post the particular tenets of their religions as well. For example, an organization by the name of Summum has won court cases against municipalities in Utah for refusing to allow the group to erect a monument of Summum aphorisms next to the Ten Commandments. The cases were won on the grounds that Summum's right to freedom of speech was denied and the governments had engaged in discrimination. Instead of allowing Summum to erect its monument, the local governments removed their Ten Commandments.

Some religious Jews oppose the posting of the Ten Commandments in public schools, as they feel it is wrong for public schools to teach their children Judaism. The argument is that if a Jewish parent wishes to teach their child to be a Jew, then this education should come from practicing Jews, and not from non-Jews. This position is based on the demographic fact that the vast majority of public school teachers in the United States are not Jews; the same is true for their students. This same reasoning and position is also held by many believers in other religions. Many Christians have some concerns about this as well; for example, can Catholic parents count on Protestant or Orthodox Christian teachers to tell their children their particular understanding of the commandments? Differences in the interpretation and translation of these commandments, as noted above, can sometimes be significant.

Many commentators see this issue as part of a wider kulturkampf (culture struggle) between liberal and conservative elements in American society. In response to the perceived attacks on traditional society other legal organizations, such as Liberty Counsel have risen to defend the traditional interpretation.

Notes

- â The term decalogue (Greek=δÎκι ÎťĎγοΚ or dekalogoi) ("ten statements") is the Greek translation of the Hebrew words found in the Septuagint.

- â The Ten Commandments are also referred to as "tables of testimony" (Exodus 24:12, Exodus 31:18, Exodus 32:16) or "tables of the covenant" (Deuteronomy 9 verses 9, 11, 15).

- â The text in Deuteronomy differs on some points with the text in Exodus.

- â Lisa Ann Bargeman, The Egyptian Origin of Christianity. (Blue Dolphin Publishing, 2005.)

- â The Hebrew word ratsach, used in this commandment, is close to the word murder; kill is a mistranslation, but it does not translate directly to the word murder. While most uses of the word ratsach are in passages describing murder, in Proverbs 22:13 a lion ratsach a man to death, many argue since a lion cannot murder anyone, murder is a flawed translation as well. Also in Joshua 20:3, ratsach is used to describe death by negligence. A closer translation would be to kill in the manner of a predatory animal. Some Jews take offense at translations which state "Thou shall not kill," which they hold to be a flawed interpretation, for there are circumstances in which one is required to kill, such as if killing is the only way to prevent one person from murdering another, or killing in self-defense.

- â Exodus 34:28, Deuteronomy 4:13, Deuteronomy 10:4 Retrieved November 2,3 2015.

- â Meshulam Margaliot , Lectures on the Torah Reading by the faculty of Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel Retrieved November 23, 2015.

- â Samaritan Pentateuch.

- â Mount Gerizim and the Samaritans.

- â Rob Schmitz, The Ten Commandments: Religious or historical symbol? Minnesota Public Radio, September 10, 2001. Retrieved November 23, 2015.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bargeman, Lisa Ann. The Egyptian Origin of Christianity. Blue Dolphin Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-1577331520

- Mendenhall George E. Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction To the Bible In Context. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001. ISBN 0664223133

- Friedman Richard Elliott. Who Wrote the Bible? Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1987. ISBN 0671631616

- Mendenhall George E. The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973. ISBN 0801812674

- Kaufmann, Yehezkel. trans. Moshe Greenberg The Religion of Israel, From Its Beginnings To the Babylonian Exile. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960.

- Wilson, Andrew (ed.), World Scripture: A Comparative Anthology of Sacred Texts. Paragon House, 1998. ISBN 978-1557787231

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- The Ten Commandments: Ex. 20 version (text, mp3), Deut. 5 version (text, mp3) in The Hebrew Bible in English.

- Ten Commandments

- Catholic Encyclopedia on the authority of the Church to transfer observance of the Lord's Day to Sunday

- The Ten Commandments, American History and American Law

- Catholic Encyclopedia: The Ten Commandments

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Decalogue

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.