Aaron

Aaron (×Öˇ×ֲר֚×;, Aharonârelated to the Egyptian Aha Rw, "Warrior Lion"), was the brother of Moses and Miriam and founder of the Jewish priesthood. Aaron was the eldest son of Amram and Jochebed (Exodus 6:16) of the tribe of Levi. Together with Moses, he led the Israelites out of Egypt after confronting the pharaoh who had enslaved them. He was also a prophet, a gifted speaker, and powerful miracle worker. His story is preserved in the biblical narratives of Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy.

Although Aaron is infamous for his role in forging the idolatrous Golden Calf, he is revered in Jewish tradition for his leadership during the early stages of the Exodus, and especially for his role as the first high priest of the Tabernacle, the sacred shrine of the Israelites until the establishment of the Temple of Jerusalem.

In Christian tradition, Aaron was the ancestor of Zechariah and Elizabeth, the parents of John the Baptist. And like the Baptist who went before Jesus to prepare his way, Aaron, as Moses' mouthpiece, prepared Moses' way before the Hebrew slaves who were reluctant to trust a royal prince of Pharaoh's family.

Aaron in the Bible

In the Book of Exodus, Aaron first enters the story when Moses, standing in front of the burning bush on Mount Sinai, asks God for help, fearing that the Hebrew slaves in Egypt will not believe him. God then appoints Aaron to be Moses' spokesperson. Aaron is called Moses' brother (Exodus 4:14); some presume that he was a respected priest within the community of Hebrew slaves, one whom the people would listen to when they would be suspicious of Moses alone, as when he killed the Egyptian (Exodus 2:14). By vouching for Moses, Aaron provides him legitimacy and crucial support among the elders of the people. The people follow Moses because Aaron speaks to them on his behalf (Exodus 4:29-31).

Miracles and plagues

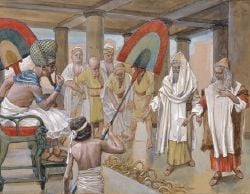

Aaron goes with Moses to approach the pharaoh of Egypt and demands that he allow God's people to leave for a three-day pilgrimage to offer sacrifice to the Lord (Yahweh). When the pharaoh refuses, Aaron takes the lead in demonstrating God's power. First, Aaron throws down his staff, and it becomes a snake. The pharaoh's magicians perform the same feat, but Aaron's snake swallows the Egyptian serpents. However, this only hardens the heart of the pharaoh against the Israelites (Exodus 7:8-13).

Next, Aaron turns the Nile to blood. Again, the Egyptian magicians accomplish the same feat, and again Pharaoh refuses to relent. Aaron then causes frogs to emerge from the Nile to plague the land. The Egyptian magicians do the same. This time Pharaoh asks Moses to pray to Yahweh to take the frogs away. God responds to Moses' entreaty, but the pharaoh again hardens his heart. Aaron now performs a miracle that the Egyptians cannot duplicate: A plague of gnats. The magicians testify, "this is the finger of God," but Pharaoh stubbornly refuses to listen. The pattern of miracles now shifts away from Aaron, and Moses takes the lead in bringing about the remaining plagues that finally force the Pharaoh to allow the Israelites to leave.

The Exodus

God gave his instruction concerning the Exodus and the commemoration of Passover to both Moses and Aaron (Exodus 12:31, 43). The Israelites obeyed Moses and Aaron during the initial Exodus, but began to question them when food became scarce (Exodus 16:2).

In response, God provided manna for the people to eat. Aaron preserved some in a jar for posterity and placed it in front of a God's altar. (Exodus 16:34) In battle against the Amalekites, Aaron held Moses' hands aloft, allowing the Israelites to prevail (Exodus 17:12). When Moses' father-in-law Jethro visited the encampment and offered sacrifices to Yahweh, Aaron came "with all the elders of Israel to eat bread with Moses' father-in-law in the presence of God" (Exodus 18:12).

Aaron on Sinai

Aaron alone was commanded to join Moses when Moses first ascended Mount Sinai to receive the Ten Commandments verbally, while other priests, elders, and the common people were forbidden to do so. (Exodus 19:24) Later Aaron ascended the sacred mountain again with Moses and the 70 elders of Israel, at which time God's covenant with the Israelites was confirmed and the priesthood was formally initiated. This version of the story relates that Aaron was among those who actually "saw the God of Israel."

Aaron's priesthood

Moses left Aaron and Hur in charge as he ascended the mountain once more, this time with Joshua, to receive the Ten Commandments in written form. The majority of God's communication to Moses during his 40 days on the mountain concerned priestly issues such as the Tabernacle, the Ark of the Covenant, the sacred altars, and detailed instructions about priestly vestments. The role of Aaron is particularly emphasized.

Have Aaron your brother brought to you⌠along with his sons Nadab and Abihu, Eleazar and Ithamar, so they may serve me as priests. Make sacred garments for your brother Aaron, to give him dignity and honor⌠Make the ephod of gold, and of blue, purple and scarlet yarn, and of finely twisted linenâthe work of a skilled craftsman⌠Whenever Aaron enters the Holy Place, he will bear the names of the sons of Israel over his heart on the breastplate of decision as a continuing memorial before the Lord. Also put the Urim and Thummim in the breastplate, so they may be over Aaron's heart whenever he enters the presence of the Lord. Thus Aaron will always bear the means of making decisions for the Israelites (Exodus 28:1-30).

God further instructed Moses to formally initiate Aaron and his sons as the official priests of Israel. Moses received instructions on the process of consecration, as well as on the offering of sacrifices, incense, and other priestly duties to be carried out by Aaron and his descendants.

The Golden Calf

Ironically, just as Moses was receiving these commands which would give Aaron's lineage the place of highest honor, Aaron himself was about to commit the sin for which he would always be remembered. The people lost faith in Moses because of his long absence, demanding that Aaron make them an image for them to worship. Aaron complied with their demand by fashioning a golden calf out of their jewelry, declaring, "These are your 'gods' who led you out of Egypt." While most English translations read "make us gods," the Hebrew is `asah 'elohiymâ"elohiym" being the same word normally translated as "God." Aaron's act led the people to the sin of idolatry, for God had already commanded them not to make "graven images." Moreover, the text makes it plain that in their worship of Elohiym's image, the people not only offered burnt offerings and fellowship offerings, but "indulged in revelry" and "ran wild."

Unity between Aaron and Moses was crucial for the success of Moses' mission. Hence, when the people demanded a Golden Calf, it was for Aaron to stand firm as Moses' representative. But he failed, and out of weakness he acceded to the people's demands to lead them in building the idol. Accordingly, this destroyed the foundation for the Ten Commandments and the Tabernacle that Moses sought to establish through 40 days of fasting on the mountain. When Moses descended the mountain and saw the people worshiping the Golden Calf, he broke the tablets of the Ten Commandments and reprimanded Aaron for allowing the people to sin so grievously (Exodus 32:21). Aaron lamely excused himself on the grounds that the people are "prone to evil."

Aaron received no immediate punishment for the deed. Instead, Moses called Aaron and his fellow Levites to purge the evil by conducting a mass slaughter of 3,000 peopleâbrothers, friends, and neighborsâat Moses' command. By this condition, Moses could reaffirm the Levites' special status, declaring: "You have been set apart to the Lord today, for you were against your own sons and brothers, and he has blessed you this day" (Exodus 32:29). He also ordered the people to strip off their jewelry. Then Moses again climbed Mount Sinai to fast a second time for 40 days in order to recover the Ten Commandments and the Tabernacle. His fast would also have the effect of restoring Aaron's mistake. After this, Aaron and the people united to build the Tabernacle and continue on their journey. God confirmed his support for Aaron's priesthood at the time of Aaron's first offerings as high priest of the Tabernacle and again after Korah's rebellion when Aaron's staff miraculously blossomed.

Leviticus

As the name implies, the Book of Leviticus is largely concerned with the tribe of Levi and the role of Israel's priesthood. In this book, Aaron and his sons are mentioned more than Moses. Their sacrificial duties, vestments, and rights to a share of various offerings are described in great detail (Lev. 1-7).

In Leviticus 8, Aaron and his sons are formally ordained. Moses ceremonially washes and dresses them, and then anoints Aaron as the chief priest. After conducting several animal sacrifices, he places some of the sacrificial blood "on the lobe of Aaron's right ear, on the thumb of his right hand and on the big toe of his right foot." Moses then consecrates Aaron's sons by sprinkling them with sacrificial blood and anointing oil. To complete the act of atonement and consecration, Aaron and his sons must remain in the sacred tent for seven days after consuming a sacrificial meal.

On the eighth day, Aaron assumes his duties as high priest, carefully conducting various offerings. God signals his approval of Aaron's work by sending fire from heaven to consume the sacrifices Aaron has offered (Lev 9:24).

Later, the importance of carrying out the priestly duties meticulously is emphasized when Aaron's sons Nadab and Abihu use "unauthorized fire" in attending the altar and are immediately slain by God for this sin (Lev. 10:1). Upon hearing Moses' explanation that this was done to show God's absolute holiness, Aaron "remains silent," neither mourning, nor protesting. Moses appoints Mishael and Elzaphan, cousins of Aaron and Moses, to replace the slain priests. He commands Aaron's family not to tear their priestly clothesâtraditional Jewish signs of mourningâupon pain of death.

Aaron conveys to the people various dietary laws. God reveals to Moses and Aaron new instructions concerning skin diseases, mildew in a house, ritual impurity, and bodily discharges. Through Moses, God instructs Aaron to enter the Holy of Holies only once a year on the Day of Atonement. God also stipulates that Aaron's descendants are not allowed to serve at the sacrificial altar if they have various physical defects, although they may still partake of the sacrificial meals (Lev 21:17:22).

Controversies in Numbers

The Book of Numbers contains several controversial stories regarding the relative position of Aaron vis a vis Moses and vis a vis other Levites. Some scholars believe these stories reflect later rivalries between Aaronic and Levitical priesthoods during the period of the Judges which were finally resolved in the seventh century B.C.E. with the supremacy of the Aaronic priestly lineage confirmed by the Deuteronomic reforms of Hezekiah (Deuteronomy 12). Others see these controversies as a continuation of a simmering mistrust that may have developed between Moses and Aaron from the time of Aaron's sin in the incident of the Golden Calf.

Miriam's leprosy

In Numbers 12, Aaron and Miriam speak against Moses because he has married a Cushite woman. God calls them and Moses to him at the sacred tent, where he explains that Moses' position is above that of all other prophets, since Moses alone speaks to God "face to face." God grows angry with Aaron and Miriam, and Miriam turns leprous. Aaron pleads for her healing with Moses, and Moses pleads with God, but God declares that Miriam must spend seven days confined alone outside of camp as punishment.

Korah's rebellion

In Numbers 16, a Levite leader named Korah, together with a large group of respected Israelites, protests the special status of Moses and Aaron by saying, "The whole community is holy, every one of them, and the Lord is with them. Why then do you set yourselves above the Lord's assembly?"

Moses declares that it is against God, not simply Aaron and himself, that this complaint is made. Moses challenges Korah to bring his upstart priests to the sacred tent and let Yahweh himself decide the matter. Many of Korah's followers and their families are soon killed as "the earth opened its mouth and swallowed them, with their households⌠They went down alive into the grave, with everything they owned." God also sends fire to consume the disciples of Korah who, standing at the holy tent, had attempted to usurp and democratize the priesthood. In the aftermath, Aaron's son Eleazer begins to emerge as a faithful successor to his father. Meanwhile, God has sent a plague against the Israelites generally, killing another 14,700 in addition to those killed earlier. Aaron makes atonement for them, and soon the plague stops.

Aaron's Rod

To further demonstrate God's support for Aaron's priesthood, Moses collects one staff from each of the 12 tribes. On Levi's staff, Aaron's name is inscribed. The staves are placed before God's altar in the holy tent, and the next day, Aaron's staff has miraculously sprouted, budded, blossomed, and produced almonds (Num. 17:8).

Phineas's consecration at Baal Peor

In Numbers 25, the Israelites go astray worshiping Baal with the Midianites and engaging in licentious rites, with the result that God sends a plague upon Israel. Aaron's grandson, Phineas, stands up to the challenge and killed an Israelite chief and Midianite woman engaged in ritual intercourse, thrusting his spear through the both of them. His righteous deed stops the plague, and Moses consecrates Phineas as the ancestor of a "perpetual priesthood."

Death of Aaron

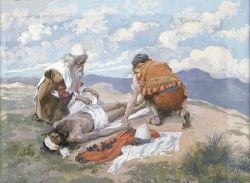

As the Israelites prepare finally to enter Canaan, God tells Moses to bring Aaron to a place called Mount Hor together with Aaron's son Eleazer. There, Aaron is to die, and Eleazer is to be invested with the office and garments of the high priest. "When the whole community learned that Aaron had died, the entire house of Israel mourned for him thirty days" (Num. 20:29).

Legacy

Despite his sin in the matter of the Golden Calf and his apparent failure to intervene and stop Moses from striking the rock, Aaron's position as the ancestor of the Israelite priesthood was confirmed by his faithful attendance to God at the Tabernacle and his loyalty to Moses throughout most of the 40 years in the wilderness. His priesthood was confirmed by two miraculous signsâthe sending of fire from heaven to consume his first offering as high priest, and the later flowering of his staff after Korah's rebellion against his priesthood. His legacy was sealed by his grandson Phineas, who at the plague of Baal Peor (Num. 25) stood strongly with Moses to stop the Israelites from slipping into idolatry.

The Aaronic priesthood, together with that of the Israelite monarchy and the prophets, was a key factor in the history of Israel, especially so in Jerusalem, where the priesthood held significant political power through the Temple. Several young kings were trained and guided by Aaron's descendants, and at times Aaronic priests were involved in violent political coups and counter-coups. The Aaronic priesthood was also the single most important institution in the creation of the Jewish scripture and the survival of the Jewish tradition after the Babylonian exile. Some Jews expected both a kingly Messiah of Davidic lineage, and a priestly Messiah, of Aaronic lineage.

In Christian tradition, Aaron was the ancestor of John the Baptist, whose parents were both of priestly lineages. Jesus Christ was possibly a descendant of Aaron on his mother's side, since his mother Mary was a cousin of Elizabeth, John the Baptistâs mother.

The vast majority of Jews today are considered descendants of the tribe of Judah. However, a minority claim Levite descent, and some claim to be Kohanimâof the priestly lineage of Aaron. Jewish family names such as Levy and Levin often denote such a supposed Levite genealogy. Names such Cohen and Kohn denote Aaronic descent. While no written genealogies date back nearly so far as to confirm this claim, recent genetic studies have indeed presented some basis for it.[1]

Aaron in Islam

Aaron, known as Harun, is recognized as both a priest and a prophet in Islam. Islamic tradition sees his role as comparable to that of Ali in relation to the Prophet Muhammad, who reportedly said: "Will you (Ali) not be pleased that you will be to me like Aaron to Moses? But there will be no prophet after me" (Sahih Bukhari, Volume 5, Book 57, Number 56).

A significant difference between Harun in the Qur'an and Aaron in the Bible is that Harun was not involved with the creation of the Golden Calf. Rather, he did not prevent it, as he feared for his life at the hands of the idol makers.

Critical views

Due to Aaron's ambiguous relationship with Moses, the biblical representation of his character is sometimes negative and dark. However, the Bible also exhibits many examples of his faithful service and God's continued support of his position as high priest.

Scholars who accept the documentary hypothesis distinguish various portrayals of Aaron in different sources:

- Aaron as fallibleâThe Elohist "[E]" represents Aaron as a fallible priest who commits serious sin. Although he comes to meet Moses (Exodus 4:14), supports him in war, (Exodus 17:12) and upholds the law (Exodus 24:14), Aaron yields to the people and makes the Golden Calf (Exodus 32). He also joins with Miriam when she criticizes Moses for marrying a Cushite woman. (Numbers 12) Some believe the story of the Golden Calf reflects the Elohist's opposition to the northern shrine at Bethel, which feature a golden or bronze bull-calf icon.

- Aaron as Moses's prophetâIn the Yahwist "[J]" representation Aaron does not figure as negatively. J's version does not speak of the Golden Calf, and Aaron appears as a powerful miracle worker with Moses when the two confront Pharaoh. He partakes in the covenant meal on Sinai (Exodus 24:1, 2, 9-11). However, in both J and E, Moses is the representative of God, while Aaron is Moses' prophet (Exodus 4:16, 7:1).

- Aaron as idolatrousâThe Deuteronomist "[D]" account mentions Aaron only sparingly, but remembers him very negatively. In Deuteronomy 9, Aaron is directly responsible for the building of the Golden Calf. Yahweh is so angry toward Aaron that he is about to destroy him. The account of Aaron's death in Deuteronomy 10:6 is different from that in Numbers 20:22, coming at Moserah instead of Mount Horâmuch earlier in the storyâand is the result of the incident of the Golden Calf, not striking the rock at Kadesh.

- Aaron as archetypeâIn the Priestly source "[P]" and its various subdivisions, Aaron is referred to even more than Moses. In Exodus 25-30 and 35-40, and especially in Leviticus and Numbers, Aaron is the archetypal priest. When his position is challenged, God upholds it. His role emphasizes the critical importance of authority in the later Temple priesthood. What was done for Aaron (in terms of honor and respect) is what should be done for any high priest. The ceremonial investiture prescribed in Exodus 28-29 and Leviticus 8 is a manual for the sanctuary ritual in the Temple of Jerusalem.

Notes

- â Skorecki K., et al. "Y chromosomes of Jewish priests," Nature 385 (32): 1997.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bright, John. A History of Israel. Westminster John Knox Press, 2000. ISBN 0664220681.

- Heap, Norman L. Moses, Aaron & Joshua. Family History Publications, 1990. ISBN 978-0945905059.

- Himmelfarb, Martha. A Kingdom of Priests: Ancestry and Merit in Ancient Judaism. University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0812239508.

- Miller, J. Maxwell. A History of Ancient Israel and Judah. Westminster John Knox Press, 1986. ISBN 066421262X.

- Skorecki K., et al. "Y chromosomes of Jewish priests," Nature 385 (32): 1997.

External links

All links retrieved June 13, 2023.

- Aaron Catholic Encyclopedia

- Aaron, the High Priest by David Mandel

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.