Esther, Book of

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (20 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{Paid}} |

| − | + | {{epname|Esther, Book of}} | |

| + | [[Image:Rembrandt Harmenszoon van Rijn- Assuerus, Haman and Esther.JPG|thumb|350px|Rembrandt's portrayal of Esther, King Ahasuerus (center), and the evil Haman at their banquet.]] | ||

| + | The '''Book of Esther''' is a book of the [[Hebrew Bible]] and of the Christian [[Old Testament]]. Also known to Jews as the '''Megillah''' (Scroll) it is the basis for the [[Jewish]] celebration of the joyous holiday of [[Purim]]. Traditionally, its full text is read aloud twice during the celebration. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The ''Book of Esther'' is set in the third year of [[Ahasuerus]], a king of Persia usually identified with [[Xerxes I of Persia|Xerxes I]], although other identifications have been suggested. It tells a story of palace intrigue and a plot to commit [[genocide]] against the Jews, which is thwarted by Esther, a beautiful Jewish maiden who becomes Queen of [[Persia]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The book's fairy tale-like plot makes it popular reading, although its ending—in which the Jews take mass vengeance on their enemies—raises [[ethics|ethical]] problems. The Catholic and Orthodox versions of ''Esther'', based on the Greek [[Septuagint version]], differ significantly from that of the Hebrew Bible and most [[Protestant]] versions. The historicity of the book is also controversial, in that there is no record of such a person as Esther or most other major characters and events of the book in the history of [[Persia]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Plot summary== | ||

| + | [[Image:esthermillais.jpg|thumb|250px|''Esther'' by [[John Everett Millais]], depicting Esther visiting the king to inform him of the plot.]] | ||

| + | Ahasuerus, the king of [[Persia]], is married to the beautiful Queen [[Vashti]]. He holds an opulent banquet for seven days to display his wealth, while Vashti hosts a similar feast for the noble women. At the climax of the feasting, while tipsy from wine, Ahasuerus commands Vashti to appear at the main banquet "with the crown royal, to show the people and the princes her beauty." When she refuses, he burns with anger. After consulting his advises he determines to banish her from his presence and publicly declares a search for a woman worthy to replace her as Queen. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Mordecai]]'s cousin Hadassah is selected from the candidates to be Ahasuerus's new wife and assumes the name of [[Esther]]. She does not reveal her family background as a Jew. At the city gate, Mordecai overhears two men plotting against the king. He reports them to Esther, who provides this intelligence to the Ahasuerus, giving Mordecai credit. (Chapter 2) | ||

| + | |||

| + | The King's wicked prime minister [[Haman (Judaism)|Haman]] takes offense because Mordecai refuses to kneel before him. Haman retaliates by convincing Ahasuerus to authorize him to deal with the Jews as he pleases. Using the king's own signet ring, Haman causes an edict to be sent throughout the land ordering the Jews, including women and children, to be killed and their properties plundered. (Chapter 3) Informed by Mordecai of Haman's role in the plot, Esther agrees to help at the risk of her own life, asking that Mordecai mobilize all the Jews of the capital city of [[Susa]] (Latin [[Seleucia]], modern Shush in [[Iran]]) to join her in fasting and praying for three days. (Chapter 4) | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Homemade hamantaschen.jpg|thumb|left|Hamantashen, the fruit-filled pastries shaped like Haman's three-corned hat, eaten by Jewish children of all ages at Purim.]] | ||

| + | Esther devises a scheme by which she will not only save her people, but expose the evil Haman at the same time. Haman prepares to have Mordecai publicly executed. Ahasuerus, meanwhile, is reminded of Mordecai's loyalty and wishes to reward him. He asks Haman: "What should be done for the man the king delights to honor?" Thinking that the king refers to Haman himself, the greedy minister replies that he should be given a public parade with great honor. The king immediately honors Mordecai in the manner Haman suggested. (Chapters 5-7) | ||

| + | |||

| + | The king hosts a banquet for Esther and Haman, in which she warns Ahasuerus of Haman's plot to kill all the Jews, including the loyal Mordecai. Haman is hung on the high gallows that Haman had had built for Mordecai, and Mordecai becomes prime minister in Haman's place. The king authorizes Esther to write a new decree regarding the Jews, which he will authorize. The edict entitles the Jews to take up arms and fight to kill their enemies. The Jews institute a period of feasting and celebration. (Chapter 8) They then kill 500 of their enemies in Susa, hanging the ten sons of Haman. In the surrounding provinces another Jewish force killed another 75,000 of their enemies. The feast of Purim is then instituted as a joyous celebration of their victory and their release from the edict of persecution. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Authorship, date, an canonicity== | ||

{{Books of the Old Testament}} | {{Books of the Old Testament}} | ||

| − | The '''Book of Esther''' is a | + | [[Image:Göttingen-Esther.Rolle.0.JPG|thumb|left|250px|Scroll of Esther (Megillah)]]Traditionally, ''Esther'' is usually dated to the third or fourth century B.C.E. However, critical scholarship dates it to the second century. The book's authorship is sometimes attributed to Mordecai himself, but is in fact anonymous. |

| + | |||

| + | A singular characteristic of the book is that it does not mention God. This, together with its militant nationalistic outlook caused its inclusion in both the Jewish and Christian Bibles problematic. Its ending is also problematic in the killing of Haman's sons appears to violate the commandment of Deuteronomy 24:16: "Fathers shall not be put to death for their children, nor children put to death for their fathers..." | ||

| + | |||

| + | ''Esther'' is the one book of the Hebrew Bible not found among the [[Dead Sea Scrolls]]. Jewish editors of Greek [[Septuagint]] translation included numerous verses demonstrating the religious piety of both Esther and Mordecai. Roman Catholic and Orthodox versions included these additions as canonical, while they are not included in the [[Hebrew Bible]] and most [[Protestant]] versions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Debate over historicity== | ||

| + | The historical accuracy of the ''Book of Esther'' is disputed. For the last 150 years, critical scholars have seen the ''Esther'' as a work of fiction, while traditionalists argue in favor of the story being historical. | ||

| + | |||

| + | As early as the [[eighteenth century]], the lack of clear corroboration of the details of the story with what was known of [[Persian history]] from classical sources led scholars to doubt that the book was historically accurate. It was argued that the form of the story—with its [[Cinderella]]-like plot—seems closer to that of a romance than a work of history, and that many of the events depicted therein are implausible and unlikely. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Aert de Gelder 004.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Mordecai and Esther, by Aert de Gelder, c. 1985.]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | From the late nineteenth century onwards, scholars explored the theory that the story is not only a myth related to the festival of [[Purim]], but may have been related to older [[Mesopotamia]]n legends. According to this interpretation the tale celebrates the triumph of the Babylonian deities [[Marduk]] (Mordecai) and [[Ishtar]] (Esther) and/or the renewal of life in the spring. Although this view is not widely held by the religious scholars today, it remains well known. It is explored in depth in the works of [[Theodore Gaster]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Traditionalists argue that Esther derives from real history. They argue that because the feast of Purim is integral to Jewish history, there is strong reason to believe this story is indeed based upon a true, though obscure, historical event. Also, parallels between [[Herodotus]]' account of [[Xerxes 1]] and the events in ''Esther'' have been noted. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Others have argued for different identifications, particularly noting traditions referring to Ahasuerus as "[[Artaxerxes]]" in Greek. In 1923, Jacob Hoschander wrote ''The Book of Esther in the Light of History'', in which he posited that the events of the book occurred during the reign of [[Artaxerxes II]] Mnemon, in the context of a struggle between adherents of the basically monotheistic [[Zoroastrianism]] and those who wanted to bring back the [[Magi]]an worship of [[Mithra]] and [[Anahita]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Some Christian readers consider this story to contain an allegory, representing the interaction between the church as 'bride' and [[God]]. This reading is related to the allegorical reading of the [[Song of Solomon]] and to the theme of the Bride of God, which in Jewish tradition manifests as the [[Shekinah]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Additions to ''Esther''== | ||

| + | Additions to Esther account for six appended chapters in the Latin [[Vulgate]] version of the text and later editions based on the Vulgate. These additions were originally interspersed in the Greek [[Septuagint]] version. They were recognized by [[Saint Jerome]] as additions not present in the Hebrew text, and he placed them at the end of his Latin translation as chapters 10:4-16:24. The extra chapters include several prayers to God, as well as other additions and differences. The Septuagint version noticeably calls Haman a [[Macedonia]]n where the Hebrew text describes him as an Agagite, implying he was descended from the [[Amalekite]] leader Agag. | ||

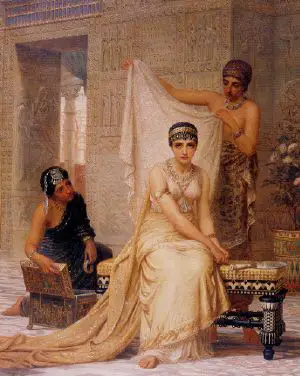

| − | + | [[Image:Esther haram.jpg|thumb|Esther readies herself to meet the king: [[Edwin Long]], 1878.]] | |

| − | + | The canonicity of the Greek additions has been a subject of scholarly disagreement practically since their first appearance in the [[Septuagint]]. Rabbinical authorities rejected the Septuagint, opting for the version retained in the [[Masoretic text]] of the [[Hebrew Bible]]. [[Martin Luther]] was a vocal [[Reformation]]-era critic of the work, considering even the original Hebrew version to be of very doubtful value. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | [[ | + | The [[Council of Trent]], representing the summation of the [[Roman Catholic]] [[Counter-Reformation]], declared the entire book, both Hebrew text and Greek additions, to be canonical. The ''Book of Esther'' is used twice in commonly used sections of the [[Catholic Lectionary]]. In both cases, the text is taken from a Greek addition, including the prayer of [[Mordecai]]. The [[Eastern Orthodox Church]] also uses the Septuagint version of ''Esther'', as it does for the entire [[Old Testament]]. The additions are specifically considered as scriptural in the [[Thirty-Nine Articles]] of the [[Church of England]]. |

| − | + | Based on the origin of the Septuagint in the Jewish community of [[Alexandria]], scholars suggest that the ''Additions to Esther'' are the work of an Egyptian Jew, writing around 170 B.C.E., who sought to give the book a more religious tone, suggesting that the Jews were saved from destruction because of their piety rather than primarily the cleverness of Mordecai and Esther. | |

| − | + | Modern Roman Catholic scholars usually recognize the Greek additions having been written later than the original. Some modern Catholic English Bibles restore the Septuagint order and indicate with footnotes that the additions do not appear in the Hebrew text.<ref>[http://www.nccbuscc.org/nab/bible/index.htm#esther Esther] in the [[New American Bible]]. Retrieved February 12, 2008.</ref> | |

==Timeline of Major Events== | ==Timeline of Major Events== | ||

| Line 26: | Line 68: | ||

| 369 B.C.E. | | 369 B.C.E. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Ahasuerus's 180-day feast; Queen Vashti exiled, Queen Vashti was replaced by king Ahasuerus(according to | + | | Ahasuerus's 180-day feast; Queen Vashti exiled, Queen Vashti was replaced by king Ahasuerus (according to Christian Beliefs) (killed according to Jewish tradition) |

| 366 B.C.E. | | 366 B.C.E. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 32: | Line 74: | ||

| Tevet, 362 B.C.E. | | Tevet, 362 B.C.E. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Haman casts lots to choose date for Jews' annihilation | + | | Haman casts lots to choose a date for the Jews' annihilation |

| Nissan, 357 B.C.E. | | Nissan, 357 B.C.E. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 38: | Line 80: | ||

| Nissan 13, 357 B.C.E. | | Nissan 13, 357 B.C.E. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Mordecai calls on Jews to repent; | + | | Mordecai calls on Jews to repent; three-day fast ordered by Esther |

| Nissan 14-16, 357 B.C.E. | | Nissan 14-16, 357 B.C.E. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| − | | Esther goes to Ahasuerus; hosts | + | | Esther goes to Ahasuerus; hosts first wine party with Ahasuerus and Haman |

| Nissan 16, 357 B.C.E. | | Nissan 16, 357 B.C.E. | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Line 54: | Line 96: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Celebrations everywhere, except Shushan where second day of battles are fought | | Celebrations everywhere, except Shushan where second day of battles are fought | ||

| − | | | + | | Adar 14, 356 B.C.E. |

|- | |- | ||

| Celebration in Shushan | | Celebration in Shushan | ||

| Line 65: | Line 107: | ||

<br/> | <br/> | ||

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | + | <references /> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Greenspoon, Leonard J., and Sidnie White Crawford. ''The Book of Esther in Modern Research''. Sheffield Academic Pr, 2003. ISBN 978-0826466631 | |

| + | * Hoschander, Jacob. ''The Book of Esther in the Light of History''. Philadelphia: Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning, 1923. {{OCLC|613337}} | ||

| + | * Laniak, Timothy S. ''Shame and Honor in the Book of Esther''. Atlanta, Ga: Scholars Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0788505058 | ||

| + | * Moore, Carey A. ''Studies in the Book of Esther''. The Library of Biblical studies. New York: Ktav Pub. House, 1981. ISBN 978-0870687181 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 17, 2023. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * [http://www.chabad.org/library/archive/LibraryArchive2.asp?AID=15782 Translation with Rashi's commentary] ''Chabad.org'' | |

| − | + | *[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=483&letter=E Esther in the Jewish Encyclopedia''] ''jewishencyclopedia.com'' | |

| − | + | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05549a.htm Esther in the Catholic Encyclopedia] newadvent.org | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=483&letter=E | ||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/05549a.htm | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | {{Books of the Bible}} | ||

| + | [[Category:Bible]] | ||

[[Category:religion]] | [[Category:religion]] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] |

| − | |||

{{Credit|163938621}} | {{Credit|163938621}} | ||

Latest revision as of 07:27, 17 November 2023

The Book of Esther is a book of the Hebrew Bible and of the Christian Old Testament. Also known to Jews as the Megillah (Scroll) it is the basis for the Jewish celebration of the joyous holiday of Purim. Traditionally, its full text is read aloud twice during the celebration.

The Book of Esther is set in the third year of Ahasuerus, a king of Persia usually identified with Xerxes I, although other identifications have been suggested. It tells a story of palace intrigue and a plot to commit genocide against the Jews, which is thwarted by Esther, a beautiful Jewish maiden who becomes Queen of Persia.

The book's fairy tale-like plot makes it popular reading, although its ending—in which the Jews take mass vengeance on their enemies—raises ethical problems. The Catholic and Orthodox versions of Esther, based on the Greek Septuagint version, differ significantly from that of the Hebrew Bible and most Protestant versions. The historicity of the book is also controversial, in that there is no record of such a person as Esther or most other major characters and events of the book in the history of Persia.

Plot summary

Ahasuerus, the king of Persia, is married to the beautiful Queen Vashti. He holds an opulent banquet for seven days to display his wealth, while Vashti hosts a similar feast for the noble women. At the climax of the feasting, while tipsy from wine, Ahasuerus commands Vashti to appear at the main banquet "with the crown royal, to show the people and the princes her beauty." When she refuses, he burns with anger. After consulting his advises he determines to banish her from his presence and publicly declares a search for a woman worthy to replace her as Queen.

Mordecai's cousin Hadassah is selected from the candidates to be Ahasuerus's new wife and assumes the name of Esther. She does not reveal her family background as a Jew. At the city gate, Mordecai overhears two men plotting against the king. He reports them to Esther, who provides this intelligence to the Ahasuerus, giving Mordecai credit. (Chapter 2)

The King's wicked prime minister Haman takes offense because Mordecai refuses to kneel before him. Haman retaliates by convincing Ahasuerus to authorize him to deal with the Jews as he pleases. Using the king's own signet ring, Haman causes an edict to be sent throughout the land ordering the Jews, including women and children, to be killed and their properties plundered. (Chapter 3) Informed by Mordecai of Haman's role in the plot, Esther agrees to help at the risk of her own life, asking that Mordecai mobilize all the Jews of the capital city of Susa (Latin Seleucia, modern Shush in Iran) to join her in fasting and praying for three days. (Chapter 4)

Esther devises a scheme by which she will not only save her people, but expose the evil Haman at the same time. Haman prepares to have Mordecai publicly executed. Ahasuerus, meanwhile, is reminded of Mordecai's loyalty and wishes to reward him. He asks Haman: "What should be done for the man the king delights to honor?" Thinking that the king refers to Haman himself, the greedy minister replies that he should be given a public parade with great honor. The king immediately honors Mordecai in the manner Haman suggested. (Chapters 5-7)

The king hosts a banquet for Esther and Haman, in which she warns Ahasuerus of Haman's plot to kill all the Jews, including the loyal Mordecai. Haman is hung on the high gallows that Haman had had built for Mordecai, and Mordecai becomes prime minister in Haman's place. The king authorizes Esther to write a new decree regarding the Jews, which he will authorize. The edict entitles the Jews to take up arms and fight to kill their enemies. The Jews institute a period of feasting and celebration. (Chapter 8) They then kill 500 of their enemies in Susa, hanging the ten sons of Haman. In the surrounding provinces another Jewish force killed another 75,000 of their enemies. The feast of Purim is then instituted as a joyous celebration of their victory and their release from the edict of persecution.

Authorship, date, an canonicity

| Books of the |

Traditionally, Esther is usually dated to the third or fourth century B.C.E. However, critical scholarship dates it to the second century. The book's authorship is sometimes attributed to Mordecai himself, but is in fact anonymous.

A singular characteristic of the book is that it does not mention God. This, together with its militant nationalistic outlook caused its inclusion in both the Jewish and Christian Bibles problematic. Its ending is also problematic in the killing of Haman's sons appears to violate the commandment of Deuteronomy 24:16: "Fathers shall not be put to death for their children, nor children put to death for their fathers..."

Esther is the one book of the Hebrew Bible not found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. Jewish editors of Greek Septuagint translation included numerous verses demonstrating the religious piety of both Esther and Mordecai. Roman Catholic and Orthodox versions included these additions as canonical, while they are not included in the Hebrew Bible and most Protestant versions.

Debate over historicity

The historical accuracy of the Book of Esther is disputed. For the last 150 years, critical scholars have seen the Esther as a work of fiction, while traditionalists argue in favor of the story being historical.

As early as the eighteenth century, the lack of clear corroboration of the details of the story with what was known of Persian history from classical sources led scholars to doubt that the book was historically accurate. It was argued that the form of the story—with its Cinderella-like plot—seems closer to that of a romance than a work of history, and that many of the events depicted therein are implausible and unlikely.

From the late nineteenth century onwards, scholars explored the theory that the story is not only a myth related to the festival of Purim, but may have been related to older Mesopotamian legends. According to this interpretation the tale celebrates the triumph of the Babylonian deities Marduk (Mordecai) and Ishtar (Esther) and/or the renewal of life in the spring. Although this view is not widely held by the religious scholars today, it remains well known. It is explored in depth in the works of Theodore Gaster.

Traditionalists argue that Esther derives from real history. They argue that because the feast of Purim is integral to Jewish history, there is strong reason to believe this story is indeed based upon a true, though obscure, historical event. Also, parallels between Herodotus' account of Xerxes 1 and the events in Esther have been noted.

Others have argued for different identifications, particularly noting traditions referring to Ahasuerus as "Artaxerxes" in Greek. In 1923, Jacob Hoschander wrote The Book of Esther in the Light of History, in which he posited that the events of the book occurred during the reign of Artaxerxes II Mnemon, in the context of a struggle between adherents of the basically monotheistic Zoroastrianism and those who wanted to bring back the Magian worship of Mithra and Anahita.

Some Christian readers consider this story to contain an allegory, representing the interaction between the church as 'bride' and God. This reading is related to the allegorical reading of the Song of Solomon and to the theme of the Bride of God, which in Jewish tradition manifests as the Shekinah.

Additions to Esther

Additions to Esther account for six appended chapters in the Latin Vulgate version of the text and later editions based on the Vulgate. These additions were originally interspersed in the Greek Septuagint version. They were recognized by Saint Jerome as additions not present in the Hebrew text, and he placed them at the end of his Latin translation as chapters 10:4-16:24. The extra chapters include several prayers to God, as well as other additions and differences. The Septuagint version noticeably calls Haman a Macedonian where the Hebrew text describes him as an Agagite, implying he was descended from the Amalekite leader Agag.

The canonicity of the Greek additions has been a subject of scholarly disagreement practically since their first appearance in the Septuagint. Rabbinical authorities rejected the Septuagint, opting for the version retained in the Masoretic text of the Hebrew Bible. Martin Luther was a vocal Reformation-era critic of the work, considering even the original Hebrew version to be of very doubtful value.

The Council of Trent, representing the summation of the Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation, declared the entire book, both Hebrew text and Greek additions, to be canonical. The Book of Esther is used twice in commonly used sections of the Catholic Lectionary. In both cases, the text is taken from a Greek addition, including the prayer of Mordecai. The Eastern Orthodox Church also uses the Septuagint version of Esther, as it does for the entire Old Testament. The additions are specifically considered as scriptural in the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England.

Based on the origin of the Septuagint in the Jewish community of Alexandria, scholars suggest that the Additions to Esther are the work of an Egyptian Jew, writing around 170 B.C.E., who sought to give the book a more religious tone, suggesting that the Jews were saved from destruction because of their piety rather than primarily the cleverness of Mordecai and Esther.

Modern Roman Catholic scholars usually recognize the Greek additions having been written later than the original. Some modern Catholic English Bibles restore the Septuagint order and indicate with footnotes that the additions do not appear in the Hebrew text.[1]

Timeline of Major Events

The following is based on the biblical chronology, which specifies months and sometimes days. It presumes that Ahasuerus is the historical Xerxes I.

| Event | Dates |

|---|---|

| Ahasuerus ascends the throne of Persia | 369 B.C.E. |

| Ahasuerus's 180-day feast; Queen Vashti exiled, Queen Vashti was replaced by king Ahasuerus (according to Christian Beliefs) (killed according to Jewish tradition) | 366 B.C.E. |

| Esther becomes queen | Tevet, 362 B.C.E. |

| Haman casts lots to choose a date for the Jews' annihilation | Nissan, 357 B.C.E. |

| Royal decree ordering killing of all Jews | Nissan 13, 357 B.C.E. |

| Mordecai calls on Jews to repent; three-day fast ordered by Esther | Nissan 14-16, 357 B.C.E. |

| Esther goes to Ahasuerus; hosts first wine party with Ahasuerus and Haman | Nissan 16, 357 B.C.E. |

| Esther's Second wine party; Haman's downfall and hanging | Nissan 17, 357 B.C.E. |

| Second decree issued by Ahasuerus, empowering the Jews to defend themselves | Sivan 23, 357 B.C.E. |

| Battles fought throughout the empire against those seeking to kill the Jews; Haman's ten sons killed | Adar 13, 356 B.C.E. |

| Celebrations everywhere, except Shushan where second day of battles are fought | Adar 14, 356 B.C.E. |

| Celebration in Shushan | Adar 15, 356 B.C.E. |

| Megillah written by Esther and Mordecai; Festival of Purim instituted for all generations | 355 B.C.E. |

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Greenspoon, Leonard J., and Sidnie White Crawford. The Book of Esther in Modern Research. Sheffield Academic Pr, 2003. ISBN 978-0826466631

- Hoschander, Jacob. The Book of Esther in the Light of History. Philadelphia: Dropsie College for Hebrew and Cognate Learning, 1923. OCLC 613337

- Laniak, Timothy S. Shame and Honor in the Book of Esther. Atlanta, Ga: Scholars Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0788505058

- Moore, Carey A. Studies in the Book of Esther. The Library of Biblical studies. New York: Ktav Pub. House, 1981. ISBN 978-0870687181

External links

All links retrieved November 17, 2023.

- Translation with Rashi's commentary Chabad.org

- Esther in the Jewish Encyclopedia jewishencyclopedia.com

- Esther in the Catholic Encyclopedia newadvent.org

| |||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.