Saint Jerome

| Saint Jerome | |

|---|---|

St. Jerome, by Lucas van Leyden | |

| Doctor of the Church | |

| Born | ca. 342 in Stridon, Dalmatia |

| Died | 419 in Bethlehem, Judea |

| Venerated in | Roman Catholic Church Lutheran Church Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Beatified | 1747

by Benedict XIV |

| Canonized | 1767

by Clement XIII |

| Major shrine | Basilica of Saint Mary Major, Rome |

| Feast | September 30 (Catholic, Lutheran), June 15 (Orthodox) |

| Attributes | lion, cardinal clothes, cross, skull, books and writing material |

| Patronage | archaeologists; archivists; Bible scholars; librarians; libraries; schoolchildren; students; translators |

Saint Jerome (ca. 342 ‚Äď September 30, 419; Greek: őēŌÖŌÉő≠ő≤őĻőŅŌā ő£ŌČŌÜŌĀŌĆőĹőĻőŅŌā őôőĶŌĀŌĆőĹŌÖőľőŅŌā, Latin: Eusebius Sophronius Hieronymus) was an early Christian apologist, theologian, and ascetic, who is best known for his single-handed composition of a new Latin translation of the Bible. Unlike the majority of contemporaneous versions, his text was distinguished by its reliance on the Greek, Latin and Hebrew versions, rather than simply using the Septuagint text of the Old Testament. As a result, it can be taken, "as a whole, [to be] the most reliable authority on the genuine text that remains."[1] One could argue that Jerome's Bible (the Vulgate) is the most important version of the text ever composed, as it provided the source material for virtually all translations (including the King James) for over a thousand years.

Jerome is recognized as a Saint and Doctor of the Church by the Roman Catholics, who celebrate his feast day on September 30. He is also recognized as a saint by the Eastern Orthodox Church, where he is known as Saint Jerome of Stridonium or Blessed Jerome.[2] They celebrate his life on the 15th of June.

Life

Early life

Jerome was born in Strido, a town on the border between Pannonia and Dalmatia (modern day Croatia), around 342 C.E. Even though he was born to Christian parents, he was not baptized until about 360, during an academic sojourn in Rome. There he studied under Aelius Donatus, a skillful master of argumentative, rhetorical and pedagogical techniques who trained the novice in the skills required for a career in the legal profession. At this time, Jerome also learned Koine Greek, but as yet had no thought of studying the Greek Church Fathers, or any Christian writings. He also attended debates and plays, and familiarized himself with the best examples of Latin and Greek literature, all skill that would prove immensely useful in the successful completion of his life's work.[3][4][5]

After several years in Rome, Jerome traveled with his friend Bonosus to Gaul, where he settled in Trier "on the semi-barbarous banks of the Rhine." During his willing exile from the heart of the empire, the scholar proceeded to befriend many Christians (including Rufinus), who inspired his curiosity about the specifics of his adopted faith. Not coincidentally, it was in these remote environs that he seems to have first taken up theological studies, copying (for his friend Rufinus) Hilary's commentary on the Psalms and the treatise De synodis. Not long after, he, Rufinus, and several others proceeded to Aquileia, where they dwelt in an atmosphere of peace, fellowship, and pious study for several years (c. 370-372). Some of these newfound companions accompanied Jerome when he set out on a pilgrimage through Thrace and Asia Minor into northern Syria. At Antioch, where he made the longest stay, two of his companions died and he himself was seriously ill more than once. During one of these illnesses (likely in the winter of 373-374), he had a vision of God enthroned that impelled him to renounce his secular studies in favor of the life of a Christian hermit. After this revelation, he dove into his exegetical studies with renewed vigor, apprenticing himself to Apollinaris of Laodicea, who was then teaching in Antioch and had not yet been suspected of heresy.[6]

Ascetic life

After fully recovering from his illness, Jerome decided to heed his vision and take up a life of asceticism in the harsh Syrian wastes. As such, he traveled southwest of Antioch into the desert of Chalcis (an area known as the Syrian Thebaid), where he took up residence among a loosely-organized community of Christian hermits. Intriguingly, he saw his material renunciation as compatible with the further development of his theological and exegetical scholarship, to the extent that he brought his entire library with him into his desert cell. Even so, the eremetical life proved to be extremely difficult for him, as "his skin was scorched brown, he slept on the soil, his bones protruded, he grew ragged and miserable of aspect. The only men he saw were natives, whose tongue he hardly understood, except at long intervals, when he was visited by Evagrius."[7] As an antidote to the mind-crushing tedium of desert life (and a means of pushing aside impure thoughts), Jerome applied himself to the task of learning Hebrew, under the guidance of a converted Jew.[8]

In Constantinople

Soon after, the Antiochene Church was riven by the Meletian schism, a circumstance that began to politicize the nearby desert. Although Jerome reluctantly accepted ordination at the hands of Bishop Paulinus (ca. 378-379), he disdained any calls to alter his scholarly, ascetic life. To this end, he soon departed from the contested territories of Antioch in favor of studying scripture under Gregory Nazianzen in Constantinople, where he remained for two to three years.[9] Several years later, his studies came to an abrupt end when Pope Damasus enjoined him to return to Rome, in order to participate in the synod of 382, which was held for the purpose of ending the Antiochene schism.

At the Vatican

In the years that followed (382-385), Jerome remained in the city as a secretary, adviser, and theological attach√© to the Vatican. He was commissioned by the pope to understake the revision of the "Old Latin Bible" (Vetus Latina), in order to offer a definitive Latin version of the text (in contrast to the divergent Latin editions then common in the West). By 384, he completed the revision of the Latin texts of the four Gospels from the best Greek texts. From around 386 (after he left Rome), he started to translate the Hebrew Old Testment into Latin. Prior to Jerome's translation, all Old Testament translations were based on the Greek Septuagint. In contrast, Jerome chose, against the pleadings of other Christians (including Augustine himself), to use the Greek source alongside the Hebrew Old Testament‚ÄĒa remarkable decision that, in retrospect, helped cement the unassailable reputation of the Vulgate version. The completion of this task, which occupied his time for approximately thirty years, is the saint's most important achievement.[10][11]

During this period, Jerome was surrounded by a circle of well-born and well-educated women, including some from the noblest patrician families, such as the widows Marcella and Paula, and their daughters Blaesilla and Eustochium. The resulting inclination of these women for the monastic life, and his unsparing criticism of the life of the secular clergy, brought a growing hostility against him amongst the clergy and their supporters. Soon after the death of his patron Damasus (December 10, 384), and having lost his necessary protection, Jerome was forced to leave his position at Rome, following an inquisition of the Roman clergy into allegations that he had improper relations with the widow Paula.

In Antioch and Bethlehem

In August 385, he returned to Antioch, accompanied by his brother Paulinianus and several friends, and followed a little later by Paula and Eustochium, who had resolved to leave their patrician surroundings and to end their days in the Holy Land. In the winter of 385, Jerome accompanied them and acted as their spiritual adviser. The pilgrims, joined by Bishop Paulinus of Antioch, visited Jerusalem, Bethlehem, and the holy places of Galilee, and then went to Egypt, the home of the great heroes of the ascetic life.

At the Catechetical School of Alexandria, Jerome listened to the blind catechist Didymus expounding upon the teachings of the prophet Hosea and reminiscing about Anthony the Great, who had died 30 years earlier. Seeing the opportunity for further spiritual growth, the saint spent some time in Nitria, admiring the disciplined community life of the numerous inhabitants of that "city of the Lord," but detecting even there "concealed serpents" (i.e., the influence of the theology of Origen). Late in the summer of 388, he returned to Palestine and settled down for the remainder of his life in a hermit's cell near Bethlehem. Although he was dedicated to a life of quiet contemplation, Jerome remained surrounded by a few friends, both men and women (including Paula and Eustochium), to whom he acted as priestly guide and teacher.[12]

Fortunately for the inchoate religious community, Paula's extravagant wealth enabled them to establish a small monastery, complete with a well-appointed library, and left them free to pursue spiritual matters. In these environs, Jerome began a period of incessant activity in literary production. To these last 34 years of his career belong the most important of his works: his version of the Old Testament from the original text, the best of his scriptural commentaries, his catalog of Christian authors, and the dialogue against the Pelagians, the literary perfection of which was acknowledged even by its detractors. To this period also belong the majority of his passionate polemics, the venom of which also distinguished him among the orthodox Fathers. As a result of his writings against Pelagianism, a body of excited partisans broke into the monastic buildings, set them on fire, attacked the inmates and killed a deacon, which forced Jerome to seek safety in a neighboring fortress (416 C.E.). However, the most unfortunate of these controversies involved his accusations of Origenistic "pollution" against Bishop John II of Jerusalem and his early friend Rufinus, both of which earned him considerable enmity.[13]

Jerome died near Bethlehem on September 30, 420. His remains, originally buried in Bethlehem, are said to have been later transferred to the church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome, although other places in the West claim some relics, including the cathedral at Nepi and the monastery of El Escorial, both of which claim to possess his head.[14]

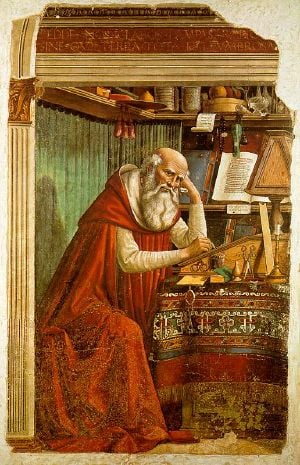

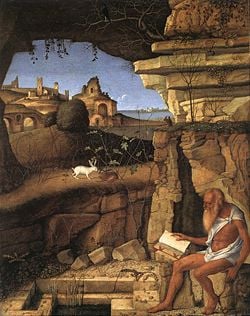

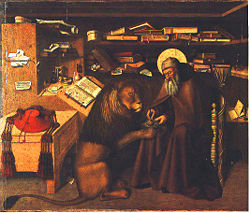

Iconographic depictions

In the artistic tradition of the Roman Catholic Church, it has been usual to represent Jerome, the patron of theological learning, as a cardinal, by the side of a Bishop (Augustine), an Archbishop (Ambrose), and a Pope (Gregory the Great). Even when he is depicted as a half-clad anchorite, with cross, skull, and Bible for the only furniture of his cell, the red hat or some other indication of his rank is, as a rule, introduced somewhere in the picture. He is also often depicted with a lion, due to a medieval story in which he removed a thorn from a lion's paw.[15]

Writings

Translations

Jerome was a scholar at a time when that statement implied a fluency in Greek. He knew some Hebrew when he started his Bible translation project, but moved to Jerusalem to perfect his grasp of the language and to strengthen his grip on Jewish scripture commentary. A wealthy Roman aristocrat, Paula, founded a monastery for him in Bethlehem‚ÄĒrather like a research institute‚ÄĒand he completed his translation there. He began in 382 by correcting the existing Latin language version of the New Testament, commonly referred to as the Itala or Vetus Latina (the "Italian" or "Old Latin" version). By 390, he turned to the Hebrew Bible, having previously translated portions from the Septuagint Greek version. He completed this work by 405 C.E..

For the next fifteen years, until he died, he produced a number of commentaries on Scripture, often explaining his translation choices. His knowledge of Hebrew, primarily required for this branch of his work, also gives his exegetical treatises (especially to those written after 386) a value greater than that of most patristic commentaries. The commentaries align closely with Jewish tradition, and he indulges in allegorical and mystical subtleties after the manner of Philo and the Alexandrian school. Unlike his contemporaries, he emphasizes the difference between the Hebrew Bible "apocrypha" (most of which are now in the deuterocanon) and the Hebraica veritas of the canonical books. Evidence of this can be found in his introductions to the Solomonic writings, to the Book of Tobit, and to the Book of Judith. Regardless of the classification of some of the books he chose to translate, the overall quality of Jerome's edition is undeniable:

His aim was to return to the original Greek, but in doing so he did not proceed as the authors of the early translations had, who were intent on extreme fidelity and literalism. Rather, he gave the text an authentically Latin structure by eliminating insufferable words and syntactical turns. He did not, however, want to replace an old translation with a new one; still less did he wish to substitute a translation in keeping with the norms of rhetoric for a popular type of translation. He was well aware that the sacred text must continue to be accessible to all, even the illiterate. He wanted it, therefore, to be syntactically and grammatically correct, but utterly understandable, and he succeeded completely.[16]

Jerome's commentaries fall into three groups:

- His translations or recastings of Greek predecessors, including 14 homilies on Jeremiah and the same number on Ezekiel by Origen (translated ca. 380 in Constantinople); two homilies of Origen on the Song of Solomon (in Rome, ca. 383); and 39e on Luke (ca. 389, in Bethlehem). The nine homilies of Origen on Isaiah included among his works were not done by him. Here should be mentioned, as an important contribution to the topography of Palestine, his book De situ et nominibus locorum Hebraeorum, a translation with additions and some regrettable omissions of the Onomasticon of Eusebius. To the same period (ca. 390) belongs the Liber interpretationis nominum Hebraicorum, based on a work supposed to go back to Philo and expanded by Origen.

- Original commentaries on the Old Testament. To the period before his settlement at Bethlehem and the following five years belong a series of short Old Testament studies: De seraphim, De voce Osanna, De tribus quaestionibus veteris legis (usually included among the letters as 18, 20, and 36); Quaestiones hebraicae in Genesin; Commentarius in Ecclesiasten; Tractatus septem in Psalmos 10-16 (lost); Explanationes in Mich/leaeam, Sophoniam, Nahum, Habacuc, Aggaeum. About 395 he composed a series of longer commentaries, though in rather a desultory fashion: first on the remaining seven minor prophets, then on Isaiah (ca. 395-ca. 400), on Daniel (ca. 407), on Ezekiel (between 410 and 415), and on Jeremiah (after 415, left unfinished).

- New Testament commentaries. These include only Philemon, Galatians, Ephesians, and Titus (hastily composed 387-388); Matthew (dictated in a fortnight, 398); Mark, selected passages in Luke, the prologue of John, and Revelation. Treating the last-named book in his cursory fashion, he made use of an excerpt from the commentary of the North African Tichonius, which is preserved as a sort of argument at the beginning of the more extended work of the Spanish presbyter Beatus of Liébana. But before this he had already devoted to the Book of Revelation another treatment, a rather arbitrary recasting of the commentary of Saint Victorinus (d. 303), with whose chiliastic views he was not in accord, substituting for the chiliastic conclusion a spiritualizing exposition of his own, supplying an introduction, and making certain changes in the text.[17]

Historical writings

One of Jerome's earliest attempts in the discipline of history was his Chronicle (or Chronicon/Temporum liber), composed ca. 380 in Constantinople; this is a translation into Latin of the chronological tables which compose the second part of the Chronicon of Eusebius, with a supplement covering the period from 325 to 379. Despite numerous errors taken over from Eusebius, and some of his own, Jerome produced a valuable work, if only for the impulse which it gave to such later chroniclers as Prosper, Cassiodorus, and Victor of Tunnuna to continue his annals.

The most important of Jerome's historical works is the book De viris illustribus, written at Bethlehem in 392: a tome whose title and arrangement were borrowed from Suetonius. It contains short biographical and literary notes on 135 Christian authors, from Saint Peter down to Jerome himself. For the first seventy-eight authors, Eusebius (Historia ecclesiastica) is the main source; in the second section, beginning with Arnobius and Lactantius, he includes a good deal of independent information (much of it describing the lives of the western theologians). Given the florescence of Christianity during this period, it is likely that the biographical details on many of these authors would have been lost without Jerome's encyclopedic summary.[18]

- Three other works of a hagiographical nature are:

- the Vita Pauli monachi, written during his first sojourn at Antioch (ca. 376), the legendary material of which is derived from Egyptian monastic tradition;

- the Vita Malchi monachi captivi (ca. 391), probably based on an earlier work, although it purports to be derived from the oral communications of the aged ascetic Malchus originally made to him in the desert of Chalcis;

- the Vita Hilarionis, of the same date, containing more trustworthy historical matter than the other two, and based partly on the biography of Epiphanius and partly on oral tradition.

- Conversely, the so-called Martyrologium Hieronymianum is spurious; it was apparently composed by a western monk toward the end of the sixth or beginning of the seventh century, with reference to an expression of Jerome's in the opening chapter of the Vita Malchi, where he speaks of intending to write a history of the saints and martyrs from the apostolic times.[19]

Letters

Jerome's letters form the most interesting portion of his literary remains, due to both the great variety of their subjects and to their compositional style. Whether he is discussing problems of scholarship, or reasoning on cases of conscience, comforting the afflicted, or saying pleasant things to his friends, scourging the vices and corruptions of the time, exhorting to the ascetic life and renunciation of the world, or breaking a lance with his theological opponents, he gives a vivid picture not only of his own mind, but of the particular zeitgeist of Christianity in the fourth century.

The letters most frequently reprinted or referred to are of a hortatory nature, such as Ep. 14, Ad Heliodorum de laude vitae solitariae; Ep. 22, Ad Eustochium de custodia virginitatis; Ep. 52, Ad Nepotianum de vita clericorum et monachorum, a sort of epitome of pastoral theology from the ascetic standpoint; Ep. 53, Ad Paulinum de studio scripturarum; Ep. 57, to the same, De institutione monachi; Ep. 70, Ad Magnum de scriptoribus ecclesiasticis; and Ep. 107, Ad Laetam de institutione filiae.[20]

Theological writings

Practically all of Jerome's productions in the field of dogma have a more or less violently polemical character, and are directed against assailants of the orthodox doctrines. Even the translation of the treatise of Didymus the Blind on the Holy Spirit into Latin (begun in Rome 384, completed at Bethlehem) shows an apologetic tendency against the Arians and Pneumatomachi. The same is true of his version of Origen's De principiis (ca. 399), intended to supersede the inaccurate translation by Rufinus. The more strictly polemical writings cover every period of his life. During the sojourns at Antioch and Constantinople he was mainly occupied with the Arian controversy, and especially with the schisms centering around Meletius of Antioch and Lucifer Calaritanus. Two letters to Pope Damasus (15 and 16) complain of the conduct of both parties at Antioch, the Meletians and Paulinians, who had tried to draw him into their controversy over the application of the terms ousia and hypostasis to the Trinity. Around the same time (ca. 379), he composed his Liber Contra Luciferianos, in which he cleverly uses the dialogue form to combat the tenets of that faction, particularly their rejection of baptism by heretics.

In Rome (ca. 383) he wrote a passionate rebuttal of the teachings of Helvidius, in defense of the doctrine of the perpetual virginity of Mary, and of the superiority of the single over the married state. An opponent of a somewhat similar nature was Jovinianus, with whom he came into conflict in 392 (in Adversus Jovinianum).[21] Once more he defended the ordinary Catholic practices of piety and his own ascetic ethics in 406 against the Spanish presbyter Vigilantius, who opposed the cultus of martyrs and relics, the vow of poverty, and clerical celibacy. Meanwhile the controversy with John II of Jerusalem and Rufinus concerning the orthodoxy of Origen occurred. To this period belong some of his most passionate and most comprehensive polemical works: the Contra Joannem Hierosolymitanum (398 or 399); the two closely-connected Apologiae contra Rufinum (402); and the "last word" written a few months later, the Liber tertius seu ultima responsio adversus scripta Rufini. The last of his polemical works is the skillfully-composed Dialogus contra Pelagianos (415).[22][23]

Evaluation of Jerome's Place in Christianity

Jerome undoubtedly ranks as the most learned of the western Fathers. As a result, the Roman Catholic Church recognizes him as the patron saint of translators, librarians and encyclopedists. He surpasses the others in many respects, though most especially in his knowledge of Hebrew, gained by hard study, and not unskillfully used. It is true that he was perfectly conscious of his advantages, and not entirely free from the temptation to despise or belittle his literary rivals, especially Ambrose.[24]

As a general rule it is not so much by absolute knowledge that he shines as by an almost poetical elegance, an incisive wit, a singular skill in adapting recognized or proverbial phrases to his purpose, and a successful aiming at rhetorical effect. He showed more zeal and interest in the ascetic ideal than in abstract speculation. It was this attitude that made Martin Luther judge him so severely.[25][26][27] In fact, Protestant readers are generally little inclined to accept his writings as authoritative, especially in consideration of his lack of independence as a dogmatic teacher and his submission to orthodox tradition. He approaches his patron Pope Damasus I with the most utter submissiveness, making no attempt at an independent decision of his own. The tendency to recognize a superior comes out scarcely less significantly in his correspondence with Augustine.[28]

Yet in spite of the criticisms already mentioned, Jerome has retained a high rank among the western Fathers. This would be his due, if for nothing else, on account of the incalculable influence exercised by his Latin version of the Bible upon the subsequent ecclesiastical and theological development. To Protestants, the fact that he won his way to the title of a saint and doctor of the Catholic Church was possible only because he broke away entirely from the theological school in which he was brought up, that of the Origenists.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ F. G. Holweck, A Biographical Dictionary of the Saints: With a General Introduction on Hagiology (Saint Louis: B. Herder Book Company, 1924), 528.

- ‚ÜĎ "Blessed" in this context does not have the sense of belonging to a lower level of sanctity, as it does in the West. For that distinction, please consult the articles on canonization and beatification.

- ‚ÜĎ Holweck, 528.

- ‚ÜĎ Alban Butler, Lives of the Saints, edited, revised, and supplemented by Herbert Thurston and Donald Attwater (Palm Publishers, 1956), 686.

- ‚ÜĎ S. Baring-Gould, The Lives of the Saints, With introduction and additional Lives of English martyrs, Cornish, Scottish, and Welsh saints, and a full index to the entire work, vol. I (Edinburgh, UK: J. Grant, 1914), 451.

- ‚ÜĎ Holweck, 528; Butler, 686-87; Baring-Gould, 452-53.

- ‚ÜĎ Baring-Gould, 454.

- ‚ÜĎ In the apocryphal accounts of Jerome's life, it was during his sojourn in the desert that he removed a thorn from a lion's paw‚ÄĒa heroic act of charity that was represented in numerous hagiographies and artistic works through Christian history. See, for example, the Middle English text of Saint Jerome and the Lion. Likewise, see the account in the Legenda Aurea: "On a day towards even Jerome sat with his brethren for to hear the holy lesson, and a lion came halting suddenly in to the monastery, and when the brethren saw him, anon they fled, and Jerome came against him as he should come against his guest, and then the lion showed to him his foot being hurt. Then he called his brethren, and commanded them to wash his feet and diligently to seek and search for the wound. And that done, the plant of the foot of the lion was sore hurt and pricked with a thorn. Then this holy man put thereto diligent cure, and healed him, and he abode ever after as a tame beast with them" (contained in Fordham University's Online Medieval Sourcebook).

- ‚ÜĎ Baring-Gould, 454-55; Butler, 687-88.

- ‚ÜĎ Baring-Gould, 457.

- ‚ÜĎ Catholic Encyclopedia, St. Jerome." Retrieved March 12, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Butler, 688-89; Baring-Gould, 458-59.

- ‚ÜĎ Holweck, 528; Butler, 689-92; Baring-Gould, 458-64.

- ‚ÜĎ Holweck, 528.

- ‚ÜĎ The lion episode, in Vita Divi Hieronymi (Migne Pat. Lat. XXII, c. 209ff.), was translated in Helen Waddell, Beasts and Saints (NY: Henry Holt, 1934).

- ‚ÜĎ Claudio Moreschini and Enrico Norelli. Early Christian Greek and Latin literature: A Literary History. (Vol. II), Translated by Matthew J. O'Connell. (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005), 309.

- ‚ÜĎ For an excellent overview of Jerome's translation and exegesis, see Rusch (76-78, 80-84) and Moreschini and Norelli (308-312).

- ‚ÜĎ William G. Rusch. The Later Latin Fathers. (London: Duckworth, 1977), 87-89¬†; Moreschini and Norelli, 318-319.

- ‚ÜĎ Moreschini and and Norelli, 307.

- ‚ÜĎ Rusch, 90-92; Moreschini and Norelli, 319-320.

- ‚ÜĎ Jerome's defense of his assault on Jovinianus can be seen in a letter addressed to his friend Pammachius (numbered 48 in collections of his letters).

- ‚ÜĎ Rusch, 84-87.

- ‚ÜĎ Francis X. Murphy in "St. Jerome: The Irascible Hermit" (A Monument to Saint Jerome) notes that "many of [Jerome]'s Catholic apologists have tried to deny, or at least to cover up‚ÄĒ usually at the expense of some innocent party‚ÄĒhis exaggeration and vituperation" (10). However, the entirety of Murphy's article (3-12) provides an excellent overview of Jerome as polemicist.

- ‚ÜĎ See Ferdinand Cavallera's "The Personality of St. Jerome" in Francis X. Murphy. A Monument to Saint Jerome (13-34).

- ‚ÜĎ See Lowell C. Green's "Faith, Righteousness, and Justification: New Light on Their Development Under Luther and Melanchton" Sixteenth Century Journal 4 (1) (April 1973): 65-86, which discusses Luther's thesis that Jerome had fundamentally misunderstood Christian faith (79).

- ‚ÜĎ For a more general picture of Luther's feelings on Jerome, see Fook Meng Cheah's A Review of Luther and Erasmus: Free Will and SalvationThe Protestant Reformed Churches in America.Retrieved March 12, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ See also Francis X. Murphy's "St. Jerome: The Irascible Hermit" in A Monument to Saint Jerome, which states that "The early Protestants pounced on him for his unrelenting polemic, and his intransigent enmities, as well as for his exact Catholicity in the matter of the Virginity of the Mother of God, the cult of relics, and the practice of bodily mortification; but above all else for his having so explicitly championed the primacy of the papacy of Rome" (10).

- ‚ÜĎ See Jerome's letters numbered 56, 67, 102-105, 110-112, 115-116; and Augustine's letters numbered 28, 39, 40, 67-68, 71-75, 81-82 (both accessible at NewAdvent.org).Retrieved March 12, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- This article uses material from the Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religion (now in the public domain)

- Baring-Gould, S. (Sabine). The Lives of the Saints, With introduction and additional Lives of English martyrs, Cornish, Scottish, and Welsh saints, and a full index to the entire work. Volume I. Edinburgh : J. Grant, 1914.

- Butler, Alban. Lives of the Saints, Edited, revised, and supplemented by Herbert Thurston and Donald Attwater. Palm Publishers, 1956. The original version is accessible online at: the Global Catholic Network.

- Cameron, A. The Later Roman Empire . London: Fontana Press, 1993. ISBN 0006861725 203

- Cutts, Edward Lewes. St. Jerome. London: Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge; New York: E. & J. B. Young, 1897.

- Farmer, David Hugh. The Oxford Dictionary of Saints. Oxford; New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0192800582.

- Holweck, F. G. A Biographical Dictionary of the Saints: With a General Introduction on Hagiology. Saint Louis: B. Herder Book Company, 1924.

- Moreschini, Claudio and Enrico Norelli. Early Christian Greek and Latin literature: A Literary History. (Vol. II). Translated by Matthew J. O'Connell. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson Publishers, 2005. ISBN 1565636066.

- Murphy, Francis X. (ed.) A Monument to Saint Jerome: Essays on Some Aspects of His Life, Works and Influence. New York: Sheed & Ward, 1952.

- Rusch, William G. The Later Latin Fathers. London: Duckworth, 1977. ISBN 0715608177.

- Saltet, Louis. "St. Jerome" in The Catholic Encyclopedia. 1910.

- Tkacz, Catherine Brown, "'Labor Tam Utilis': The Creation of the Vulgate." Vigiliae Christianae 50 (1) (1996): 42-72.

- Waddell, Helen. Beasts and Saints. NY: Henry Holt, 1934.

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

- Crawford Howell Toy and Samuel Krauss. Jewish Encyclopedia: Jerome

- St. Jerome - Catholic Online

- The Perpetual Virginity of Blessed Mary by St. Jerome

- St Jerome (Hieronymus) of Stridonium - Orthodox synaxarion

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.