Cult

A cult, strictly speaking, is a particular system of religious worship, especially with reference to its rites and ceremonies. Used in a more pejorative sense, cult refers to a cohesive social group, usually of a religious believers, which the surrounding society considers outside the mainstream or possibly dangerous. In Europe, the term "sect" is often used to describe "cults" in this sense.

During the twentieth century, groups referred to as "cults" or "sects" by governments and media became globally controversial. The rise and fall of several groups known for mass suicide and murder tarred hundreds of new religious groups of various characters, some arguably quite benign. Charges of "mind control," economic exploitation, and other forms of a abuse are routinely levied against "cults." However, scholars point out that each group is unique, and generalizations often do a disservice to the understanding of any particular group.

Controversy exists among sociologists of religion as to whether the term "cult" should be abandoned in favor of the more neutral "new religious movement." A great deal of literature has been produced on the subject, the objectivity of which is hotly debated.

Definitions

Etymologically, the word cult comes from the root of the word culture, representing the core system of beliefs and activities at the basis of a culture. Thus, every human being belongs to a "cult" in its most general sense, because everyone belongs to a culture which is conveyed by the language they speak and the habits they have formed.

The literal and traditional meaning of the word cult is derived from the Latin cultus, meaning "care" or "adoration." Sociologists and historians of religion speak of the "cult" of the Virgin Mary or other traditions of worship in a neutral sense.

Among the formal definitions of "cult" are:

- A particular system of religious worship, esp. with reference to its rites and ceremonies.

- An instance of great veneration of a person, ideal, or thing, especially as manifested by a body of admirers: The physical fitness cult.

- A group or sect bound together by veneration of the same thing, person, ideal, and so on.

- In Sociology: A group having a sacred ideology and a set of rites centering around their sacred symbols.

- A religion or sect considered to be false, unorthodox, or extremist, with members often living outside of conventional society under the direction of a charismatic leader.[1]

Most religions start out as "cults" or sects in the sense of the pejorative use of the term, that is, relatively small groups in high tension with the surrounding society. The classical example is Christianity. When it began, it was a minority system of beliefs and controversial practices such as holy communion. When it was a small "cult" or a minority group in the empire, it was often criticized by those who did not understand it or who were threatened by changes its adoption might mean. Rumors were spread by detractors about Christians drinking human blood and eating human flesh. However, when it became an official state religion and widely accepted, its practices informed activities of the culture as a whole. When a new religion becomes a large or dominant in a society the "cult" basically becomes "culture."[2]

In this sense, "cult" may be seen as a pejorative term, something akin to calling someone a "barbarian." It represents a type of in-group/out-group terminology designed to exclude one group by calling them less human or inferior. Over time, such groups tend either die to out or become more established and in less tension with society.[3]

Due to popular connotations of the term "cult," many academic researchers of religion and sociology prefer to use the term new religious movement (NRM). Such new religions are usually started by charismatic but unpredictable leaders. If they survive past the first or second generation, they tend to institutionalize, become more stable, find a greater degree of acceptance in society, and sometimes become a mainstream or even dominant religious group.

In Europe, the term "sect" tends to carry a connotation similar to the word "cult" in the U.S.

Controversies about "cults"

By one measure, between 3,000 and 5,000 purported "cults" existed in the United States in 1995.[4] Anti-cult groups in the 1970s and 80s, overly comprised of families of NRM members who objected to the newfound faith of their relative, made particularly strong accusations regarding the threat of "dangerous cults." Among the allegations levied against these groups were "brainwashing," the separation of members from their families, food and sleep deprivation, economic exploitation, and potential harm to the larger society. Some families took desperate measures to force "cult" members back into traditional faiths or a secular way of life. This led to the so-called "deprogramming" controversy, in which thousands of young adults were forcibly kidnapped and held against their will by paid agents of family members in an effort to get them to renounce their groups. Media sensationalism fueled the controversy, as did court battles which pitted expert witnesses against each other in such fields as sociology and psychology.

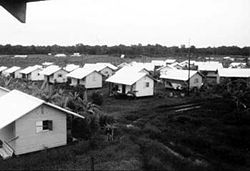

Certain groups that have been characterized as cults have clearly posed a threat to the well-being and lives of their own members and to society in general. For example, the mass suicide of over 900 People's Temple members on November 18, 1978, led to increased concern about "cults." The sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway in 1995, carried out by members of Aum Shinrikyo, renewed this concern, as did several other violent acts—both self-destructive and against society—by other groups. The number of violently destructive groups, however, is extremely small compared with the literally tens of thousands of new religious movements which are estimated to exist.[5] Thus, relatively harmless groups found themselves associated with the violent self-destructive "cult" actions in which they had no part.

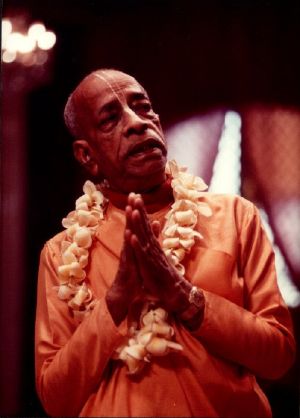

Today, some well-known NRM's remain suspect to the general public. Examples include Scientology, the Unification Church, and the Hare Krishnas. Each of these groups is now well into its second or third generation, but it is often difficult to distinguish between a group's public image—which may have become fixed decades earlier—and its current practices. Earlier "cults," such as the Mormons, Jehovah's Witnesses, Seventh Day Adventists, and Christian Scientists, are now generally considered part of the mainstream religious fabric of the American society in which they originated.

Although the majority of "cults" are religious in nature, a small number of non-religious groups are classified as as "cults" by their opponents. These may include political, psychotherapeutic or marketing groups. The term has also been applied to certain human-potential and self-improvement organizations.

Stigmatization

Because of the increasingly pejorative use of the terms "cult" over recent decades, many argue that the term should be avoided.

Researcher Amy Ryan has argued for the need to differentiate those groups that may be dangerous from groups that are more benign.[6] Ryan notes the sharp differences between definition from cult opponents, who tend to focus on negative characteristics, and sociologists, who aim to create definitions that are value-free. These definitions of religion itself has political and ethical impact beyond scholarly debate. Washington DC legal scholar Bruce J. Casino presents the issue as crucial to international human rights law. Limiting the definition of religion may interfere with freedom of religion, while too broad a definition may give some dangerous or abusive groups "a limitless excuse for avoiding all unwanted legal obligations."[7]

In 1999, the Maryland State Task Force to Study the Effects of Cult Activities on Public Senior Higher Education Institutions admitted in its final report that it had "decided not to attempt to define the world 'cult'" and proceeded to avoid the word entirely in its final report, except in its title and introduction.[8]

Leaving a "cult"

A major contention of the anti-cult movement, in the 1970s, had been that "cult members" had lost their ability to choose and only rarely left their groups without "deprogramming." This view has been largely discredited, as there are clearly at least three ways people leave a new religious movement. These are 1) by their own decision, 2) through expulsion, and 3) by intervention (exit counseling or deprogramming). ("Exit counseling" is defined as a voluntary intervention in which the member agrees to the discussion and is free to leave. "Deprogramming" involves forcible confinement against the person's will.)

Most authors agree that some people experience problems after leaving a "cult." These include negative reactions in the individual leaving the group as well as negative responses from the group such as shunning, which is practiced by some but not all NRMs and older religions alike. There are disagreements regarding the degree and frequency of such problems, however, and regarding the cause. Eileen Barker mentions that some former members may not take new initiatives for quite a long time after disaffiliation from the NRM. However, she also points out that leaving is not nearly so difficult as imagined. Indeed, as many as 90 percent of those who join a high intensity group ultimately decide to leave.[9]

Exit Counselor Carol Giambalvo believes most people leaving a cult have associated psychological problems, such as feelings of guilt or shame, depression, feeling of inadequacy, or fear, that are independent of their manner of leaving the cult.[10] However, sociologists David Bromley and Jeffrey Hadden note a lack of empirical support for alleged consequences of having been a member of a cult or sect, and substantial empirical evidence against it. They cite the fact that a large proportion of people who get involved in NRMs leave within two years; the overwhelming proportion of those who leave do so of their own volition; and that 67 percent felt "wiser for the experience."[11]

Criticism by former members

The role of former members in the controversy surrounding cults has also been widely studied by social scientists. Former members in some cases become public opponents against their former group. The former members' motivations, the roles they play in the anti-cult movement, and the validity of their testimonies are controversial. Scholars suspect that at least some of their narratives—especially concerning so-called "mind control"—are colored by a need of self-justification, seeking to reconstruct their own past, and to excuse their former affiliations, while blaming those who were formerly their closest associates.

Moreover, although some cases of abuse are incontrovertible, hostile ex-members have been shown to shade the truth and blow out of proportion minor incidents, turning them into major abuses.[12] Sociologist and legal scholar James T. Richardson contends that because there are a large number of NRMs, a tendency exists to make unjustified generalizations about them, based on a select sample of observations of life in such groups or the testimonies of (ex-)members.[13]

Governments and "cults"

Some governments have taken restrictive measures against "cults" and "sects." In the 1970s, some U.S. judges issued "conservatorship" orders revoking the freedom of an NRM to remain in his or her group so as to facilitate a deprogramming attempt. These actions were later ruled unconstitutional be higher courts. Several attempts at state legislation to legalize deprogramming likewise failed as the "mind control" theory came to be discredited in courts. However, it has been argued that the "brainwashing" theory promulgated by the anti-cult movement contributed to U.S. actions leading to the deaths of close to 100 members of the Branch Davidian group in Waco, Texas.[14] It has also been alleged that negative perceptions of a group by prosecutors was a factor in the income tax case against the Reverend Sun Myung Moon of the Unification Church, which resulted in his serving more than a year in prison in the mid 1980s.[15]

More recently, governments in Europe have sought to control "sects" through various state actions. The annual report by the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom have criticized these initiatives as "…fueled an atmosphere of intolerance toward members of minority religions." The U.S. State Department has criticized France, Germany, Russia, and several other European states for repressive measures against "sects." In Japan, deprogramming cases still find their way into the civil courts, while police allegedly refuse to bring criminal charges against the perpetrators. Meanwhile the Chinese government has become notorious for its mistreatment of members of the Falun Gong spiritual movement and other groups denounced by the government as "heretical cults."

See also

Notes

- ↑ Cult, Dictionary.com. Retrieved August 23, 2008.

- ↑ Peter L. Berger, The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion (New York: Doubleday Anchor Books 1969), 29-51.

- ↑ Stark, 1996.

- ↑ Singer, 2003.

- ↑ Barker, 1984.

- ↑ Amy Ryan, New Religions and the Anti-Cult Movement. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ↑ Bruce J. Casino, Defining Religion in American Law, Religious Freedom.

- ↑ Task Force Exectutive Summary, Religious Freedom.

- ↑ Barker, 1983.

- ↑ Carol Giambalvo, Post-cult problems.

- ↑ Brombly and Hadden, 1993, 75-97.

- ↑ Gordon Melton, Brainwashing and the Cults: The Rise and Fall of a Theory. Retrieved July 22, 2008.

- ↑ Richardson, 1989.

- ↑ D. Anthony, T. Robbins, S. Barrie-Anthony, "Cult and Anticult Totalism: Reciprocal Escalation and Violence," Terrorism and Political Violence Spring 2002: 211-240.

- ↑ Sherwood, 1991.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barker, Eileen. The Making of a Moonie: Choice or Brainwashing? Oxford: B. Blackwell, 1984. ISBN 978-0631132462

- New Religious Movements: A Practical Introduction. London: H.M.S.O., 1989. ISBN 978-0113409273

- Bromley, David G., and Jeffrey K. Hadden. The Handbook on Cults and Sects in America. Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press, 1993. ISBN 978-1559387156

- Bromley, David G., and J. Gordon Melton. Cults, Religion, and Violence. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0521668980

- Lalich, Janja. Bounded Choice: True Believers and Charismatic Cults. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. ISBN 0520240189

- Gordon, Melton J. Encyclopedic Handbook of Cults in America. New York: Garland Pub, 1992. ISBN 0815311400

- Richardson, James T. "The Psychology of Induction: A Review and Interpretation." In Marc Galanter (ed.), Cults and New Religious Movements. American Psychological Assn., 1989. ISBN 0890422125

- Sherwood, Carlton. Inquisition: The Persecution and Prosecution of the Reverend Sun Myung Moon. Washington, D.C.: Regnery, 1991. ISBN 089526532X

- Singer, Margaret Thaler. Cults in Our Midst. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2003. ISBN 0787967416

- Stark, Rodney, and William Sims Bainbridge. A Theory of Religion. New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0813523309

- Tourish, Dennis, and Tim Wohlforth. On the Edge: Political Cults Right and Left. Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 2000. ISBN 0765606399

- Zablocki, Benjamin David, and Thomas Robbins. Misunderstanding Cults: Searching for Objectivity in a Controversial Field. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2001. ISBN 0802081886

External links

All links retrieved January 11, 2024.

- Apologetics Index. www.apologeticsindex.org

- Center for Studies on New Religions. www.cesnur.org

- International Cultic Studies Association. www.icsahome.com

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.