Difference between revisions of "Judaism" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 125: | Line 125: | ||

===Jewish philosophy=== | ===Jewish philosophy=== | ||

{{main|Jewish philosophy}} | {{main|Jewish philosophy}} | ||

| − | |||

Jewish philosophy refers to the conjunction between serious study of philosophy and Jewish theology. Early Jewish philosophy was influenced by the philosophy of [[Plato]], [[Aristotle]], and [[Islamic philosophy]]. Major Jewish philosophers include [[Solomon ibn Gabirol]], [[Saadia Gaon]], [[Maimonides]], and [[Gersonides]]. Major changes occurred in response to [[The Age of Enlightenment|the Enlightenment]] (late [[1700s]] to early [[1800s]]) leading to the post-Enlightenment Jewish philosophers, and then modern Jewish philosophers such as [[Martin Buber]], [[Franz Rosenzweig]], [[Mordecai Kaplan]], [[Abraham Joshua Heschel]], [[Will Herberg]], [[Emmanuel Levinas]], [[Richard Rubenstein]], [[Emil Fackenheim]], and [[Joseph Soloveitchik]]. | Jewish philosophy refers to the conjunction between serious study of philosophy and Jewish theology. Early Jewish philosophy was influenced by the philosophy of [[Plato]], [[Aristotle]], and [[Islamic philosophy]]. Major Jewish philosophers include [[Solomon ibn Gabirol]], [[Saadia Gaon]], [[Maimonides]], and [[Gersonides]]. Major changes occurred in response to [[The Age of Enlightenment|the Enlightenment]] (late [[1700s]] to early [[1800s]]) leading to the post-Enlightenment Jewish philosophers, and then modern Jewish philosophers such as [[Martin Buber]], [[Franz Rosenzweig]], [[Mordecai Kaplan]], [[Abraham Joshua Heschel]], [[Will Herberg]], [[Emmanuel Levinas]], [[Richard Rubenstein]], [[Emil Fackenheim]], and [[Joseph Soloveitchik]]. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Jewish prayer and practice== | ==Jewish prayer and practice== | ||

Revision as of 05:04, 26 August 2008

| Category |

| Jews · Judaism · Denominations |

|---|

| Orthodox · Conservative · Reform |

| Haredi · Hasidic · Modern Orthodox |

| Reconstructionist · Renewal · Rabbinic · Karaite |

| Jewish philosophy |

| Principles of faith · Minyan · Kabbalah |

| Noahide laws · God · Eschatology · Messiah |

| Chosenness · Holocaust · Halakha · Kashrut |

| Modesty · Tzedakah · Ethics · Mussar |

| Religious texts |

| Torah · Tanakh · Talmud · Midrash · Tosefta |

| Rabbinic works · Kuzari · Mishneh Torah |

| Tur · Shulchan Aruch · Mishnah Berurah |

| Ḥumash · Siddur · Piyutim · Zohar · Tanya |

| Holy cities |

| Jerusalem · Safed · Hebron · Tiberias |

| Important figures |

| Abraham · Isaac · Jacob/Israel |

| Sarah · Rebecca · Rachel · Leah |

| Moses · Deborah · Ruth · David · Solomon |

| Elijah · Hillel · Shammai · Judah the Prince |

| Saadia Gaon · Rashi · Rif · Ibn Ezra · Tosafists |

| Rambam · Ramban · Gersonides |

| Yosef Albo · Yosef Karo · Rabbeinu Asher |

| Baal Shem Tov · Alter Rebbe · Vilna Gaon |

| Ovadia Yosef · Moshe Feinstein · Elazar Shach |

| Lubavitcher Rebbe |

| Jewish life cycle |

| Brit · B'nai mitzvah · Shidduch · Marriage |

| Niddah · Naming · Pidyon HaBen · Bereavement |

| Religious roles |

| Rabbi · Rebbe · Hazzan |

| Kohen/Priest · Mashgiach · Gabbai · Maggid |

| Mohel · Beth din · Rosh yeshiva |

| Religious buildings |

| Synagogue · Mikvah · Holy Temple / Tabernacle |

| Religious articles |

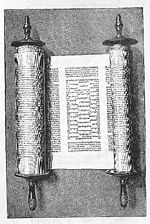

| Tallit · Tefillin · Kipa · Sefer Torah |

| Tzitzit · Mezuzah · Menorah · Shofar |

| 4 Species · Kittel · Gartel · Yad |

| Jewish prayers |

| Jewish services · Shema · Amidah · Aleinu |

| Kol Nidre · Kaddish · Hallel · Ma Tovu · Havdalah |

| Judaism & other religions |

| Christianity · Islam · Catholicism · Christian-Jewish reconciliation |

| Abrahamic religions · Judeo-Paganism · Pluralism |

| Mormonism · "Judeo-Christian" · Alternative Judaism |

| Related topics |

| Criticism of Judaism · Anti-Judaism |

| Antisemitism · Philo-Semitism · Yeshiva |

Judaism is the religious culture of the Jewish people. It is one of the first recorded monotheistic faiths and one of the oldest religious traditions still practiced today. The tenets and history of Judaism are the major part of the foundation of other Abrahamic religions, including Christianity and Islam.

While Judaism is far from monolithic in practice and has no centralized authority or binding dogma, it has remained strongly united around several religious principles, the most important of which is the belief in a single, omniscient, transcendent God that created the universe, and continues to be involved in its governance. According to Jewish thought, this God established a covenant with the Jewish people, then known as the Israelites, and revealed his laws and commandments to them in the form of the Torah. Jewish practice is devoted to the study and observance of these laws and commandments, as they are interpreted according to various ancient and modern authorities.

Judaism does not easily fit into common western categories, such as religion, ethnicity, or culture. Politically, Jews have experienced slavery, anarchic self-government, theocratic self-government, conquest, occupation, and exile. They have been in contact with and were influenced by ancient Egyptian, Babylonian, Persian, Hellenic, Christian, and Islamic cultures, as well as modern movements such as the Enlightenment and the rise of nationalism. Thus, Daniel Boyarin has argued that "Jewishness disrupts the very categories of identity, because it is not national, not genealogical, not religious, but all of these, in dialectical tension."

Religious view of Judaism's development

Much of the Hebrew Bible is an account of the Israelites' relationship with God as reflected in their history from the time of Abraham until the building of the Second Temple (ca. 350 B.C.E.).

Abraham is generally seen as the first Jew, although strictly speaking he was also the progenitor of several non-Jewish tribes as well. Rabbinic literature records that he was the first to reject idolatry and preach monotheism. As a result, God promised he would have many children: "Look now toward heaven and count the stars. So shall be your progeny." (Genesis 15:5) Abraham's first child was Ishmael and his second son was Isaac, whom God said would continue Abraham's work and inherit the Land of Israel (then called Canaan), after having been exiled and redeemed. God sent Abraham's grandson, the patriarch Jacob and his children to Egypt, where they later became enslaved. As Jacob was also known as "Israel," his tribe became known as the Israelites. God sent Moses to redeem the Israelites from slavery. After the Exodus from Egypt, God led the Jews to Mount Sinai and gave them the Torah, eventually bringing them to the land of Canaan, which they conquered at God's command.

God designated the descendants of Aaron, Moses' brother, to be a priestly class within the Israelite community. They first officiated in the Tabernacle (a portable house of worship), and later their descendants were in charge of worship in the Temple in Jerusalem.

Once the Jews had settled in the land of Israel, the tabernacle was established in the city of Shiloh for over 300 years, during which time God provided great men, and occasionally women, to rally the nation against attacking enemies sent by God as a punishment for the sins of the people, who failed to separate themselves from the Canaanites and joined in worshiping the Canaanite gods. This is described in the Book of Joshua and the Book of Judges.

The people of Israel then told Samuel the prophet, who was also the last of the judges, that they had reached the point where they needed to be governed by a permanent king, as were other nations. God acceded to this request and had Samuel appoint Saul to be their King. When Saul and disunited with Samuel and proved to lack zeal in destroying Israel's enemies, God instructed Samuel to appoint David in his stead.

David and Saul struggled with each other for many years, but once David's kingship was established, he told the prophet Nathan that he would like to build a permanent temple. God promised the king that he would allow his son to build the temple and that the throne would never depart from his children. As a result, it was David's son Solomon who built the first permanent temple in Jerusalem, as described in the Books of Kings.

However, Solomon sinned by erecting altars for his foreign wives on hilltops near Jerusalem, and after death, his kingdom was split into the two kingdoms of Israel and Judah. After several hundred years, because of rampant idolatry, God allowed Assyria to conquer Israel and exile its people. The southern Kingdom of Judah, whose capital was Jerusalem, remained under the rulership of the House of David. However, as in the north, idolatry increased to the point that God allowed Babylonia to conquer the kingdom, destroy the Temple which had stood for 410 years, and exile the people of Judah to Babylonia, with the promise that they would be redeemed after 70 years.

King Cyrus of Persian allowed the Jews to return, and, under the leadership of Ezra, and the Temple was rebuilt, as recorded in the Book of Ezra and the Book of Nehemiah. The Second Temple stood for 420 years, after which it was destroyed by the Roman general (later emperor) Titus. The Jewish temple is to remain in ruins until the Messiah, a descendant of David, arises to restore the glory of Israel and rebuild the Temple in Jerusalem.

The Torah given on Mount Sinai was summarized in the five books of Moses. Together with the books of the prophets it is called the Written Torah. The details and interpretation of the law, which are called the Oral Torah or oral law were originally unwritten. However as the persecutions of the Jews increased and the details were in danger of being forgotten, rabbinic tradition holds that these oral laws were recorded in the Mishnah and the Talmud, as well as other holy books.

Critical view

In contrast to the Orthodox religious view of the Hebrew Bible, modern scholars suggest that the Torah consists of a variety of inconsistent texts that were edited together in a way that calls attention to divergent accounts (see Documentary hypothesis).

Although monotheism is fundamental to Rabbinic Judaism, the Hebrew Bible also speaks of other gods as really existing, the Hebrew deity Yahweh being the national god of the Israelites. However, Yahweh was worshiped in many placed, not just Jerusalem, and other gods, such as Baal and Ashera, were often honored together with him. Biblical writers of the seventh century B.C.E. and later took a more firmly monotheistic view, urged complete separation from Canaanite culture, insisted that Jerusalem was the only authorized place of sacrifice to Yahweh, and wrote the history of Judah and Israel in such as way that made it appear as if the priestly ideology had always been known to the Israelites, who sinned against God by failing to adhere to it. It was only after the Babylonian exile that this priest religion became predominant. Moreover, it was primarily the tribe of Judah that constituted the people who came to be known as Jews. The religion of the Israelites, therefore, is far from identical with the biblical religion of Judaism.

Jewish denominations

Over the past two centuries the Jewish community has divided into a number of Jewish denominations. Each of these has a different understanding of what principles of belief a Jew should hold, and how one should live as a Jew.

- Orthodox Judaism holds that the Torah was written by God and dictated to Moses, and that the laws within it are binding and unchanging. Orthodox Jews generally consider a sixteenth century law code, the Shulkhan Arukh, to be the definitive codification of Jewish law. Orthodox Judaism consists of Modern Orthodox Judaism and Haredi Judaism. Hasidic Judaism is a sub-set of Haredi Judaism. Most of Orthodox Judaism holds to one particular form of Jewish theology, based on Maimonides' 13 principles of Jewish faith.

- Reform Judaism originally formed in Germany in response to the Enlightenment. Reform Judaism holds most of the commandments of the Torah to be no longer binding and initially rejected most Jewish the rituals. It emphasized instead the moral and ethical teachings of the prophets, developed a prayer service in the vernacular, and stress a personal connection to Jewish tradition over specific forms of observance. Reform rabbis are allowed to perform interfaith marriages, and mixed Jewish-Gentile families are welcome in many Reform congregation. However, many Reform congregations have returned to Hebrew prayers and encourage some degree of observance of Jewish laws and customs. Outside of the US Reform Judaism is sometimes known as Progressive Judaism or Liberal Judaism.

- Conservative Judaism. Conservative Judaism formed in the United States in the late 1800s through the fusion of two distinct groups: former Reform Jews who were alienated by that movement's emphatic rejection of Jewish law, and former Orthodox Jews who had come to question traditional beliefs and favored the critical study of sacred Jewish texts. Conservative Jews generally hold that specific Jewish laws and traditions should be retained unless there is good reason to reject them and emphasize that Jews constitute a nation as well as a religion. Conservative scholars emphasize their identification with the Amoraim, the sages of the Talmud, who embraced open debates over interpretations and developments of Jewish law. Outside of the US Conservative Judaism is known as Masorti (Hebrew for "Traditional") Judaism.

- Reconstructionist Judaism started as a stream of philosophy within Conservative Judaism, and later became an independent movement emphasizing reinterpreting Judaism for modern times.

- Secular Judaism. Though not a formal denomination, secular Judaism, also known as cultural Judaism, forms perhaps the largest group of Jews today, who do not adhere to any Jewish sect, rarely attend synagogue, and are not observant of most Jewish customs. While the majority of secular Jews believe in God, some are agnostics or atheists, while continuing to identify themselves as cultural Jews.

- Humanistic Judaism is small nontheistic movement that emphasizes Jewish culture and history as the sources of Jewish identity. Founded by Rabbi Sherwin Wine, it is centered in North America but has adherents Europe, Latin America, and Israel.

Karaism

Karaite Judaism did not begin as a modern Jewish movement. The Karaites accept only the Hebrew Bible and do not accept non-biblical writings such as the Talmud as authoritative. Some European Karaites do not see themselves as part of the Jewish community, while most do. Its followers sometimes affirm themselves they are the remnant of the non-rabbinic Jewish sects of the Second Temple period. Historically the Karaites can be traced to controversies in the Babylonian Jewish communites during the eighth and ninth centuries.

Principles of Jewish faith

While Judaism has always affirmed a number of Jewish principles of faith, no creed, dogma, or fully-binding "catechism," is recognized, an approach to Jewish religious doctrine that dates back at least 2,000 years and that makes generalizations about Jewish theology somewhat difficult.

Nevertheless, in Orthodox tradition, over the centuries, a number of clear formulations of Jewish principles of faith have appeared, many with common elements, though they differ in certain details. Of these formulations, the one most widely considered authoritative by Orthodox Jews is Maimonides' 13 principles of faith:

- God is one. This represents a strict unitarian monotheism, in which the eternal creator of the universe is the source of morality.

- God is all-powerful, as well as all-knowing, and the different [[names of God are ways to express different aspects of God's presence in the world.

- God is non-physical, non-corporeal, and eternal. All statements in the Hebrew Bible and in rabbinic literature which use anthropomorphism are held to be metaphors.

- One may offer prayer to God alone. Any belief in an intermediary between man and God, either necessary or optional, has traditionally been considered heretical.

- The Hebrew Bible, together with the teachings of the Mishnah and Talmud, are held to be the product of divine revelation.

- The words of the prophets are true.

- Moses was the chief of all prophets.

- The Torah (five books of Moses) is the primary text of Judaism.

- God will reward those who observe His commandments, and punish those who violate them.

- God chose the Jewish people to be in a unique covenant with Him.

- There will be a Jewish Messiah, or perhaps a messianic era.

- The soul is pure at birth, and human beings have free will, with an innate yetzer ha'tov (a tendency to do good), and a yetzer ha'ra (a tendency to do evil).

- People can atone for sins through words and deeds, without intermediaries, through prayer, repentance, and tzedakah (dutiful giving of charity).

The traditional Jewish bookshelf

Jews are often called the "People of the Book," and Judaism has an age-old intellectual tradition focusing on text-based Torah and Talmud study. The following is a basic, structured list of the central works of Jewish practice and thought.

- The Tanakh (Hebrew Bible)

- Works of the Talmudic Era (classic rabbinic literature):

- Midrashic Literature

- Halakhic literature

- The Major Codes of Jewish Law and Custom

- The Mishneh Torah and its commentaries.

- The Tur and its commentaries.

- The Shulhan Arukh and its commentaries.

- Other books on Jewish Law and Custom

- The Responsa literature of rabbinic rulings

- The Major Codes of Jewish Law and Custom

- Jewish Thought and Ethics

- Jewish philosophy

- Kabbalah

- Hasidic works

- Jewish ethics and the Mussar Movement

- The Siddur and Jewish liturgy

- Piyyut (Classical Jewish poetry)

- Torah databases (electronic versions of the Traditional Jewish Bookshelf)

- List of Jewish Prayers and Blessings

Jewish Law and interpretation

The basis of Jewish law is the Torah (the five books of Moses). According to rabbinic tradition there are 613 commandments in the Torah. Many laws were only applicable when the Temple in Jerusalem existed, and fewer than 300 of these commandments are still applicable today.

In addition to these written laws, most Jews have traditionally believed in what they call the Oral Law as well. This law was conveyed together with the Written Law to Moses and Sinai and handed down orally through the prophets and sages, eventually transmitted though the Pharisee sect of ancient Judaism and later recorded in written form.

In the time of Rabbi Judah Ha-Nasi (200 C.E.), much of this material was edited together into the Mishnah. Over the next four centuries this law underwent discussion and debate in both of the world's major Jewish communities Palestine and Babylonia. The commentaries on the Mishnah from each of these communities eventually came to be edited together into compilations known as the two Talmuds, the Palestinian and the Babylonia, the latter being the more authoritative today. These in turn have been expounded by commentaries of various Talmudic scholars during the ages.

Halakha is thus based on a combined reading of the Torah, and the oral tradition, including the Mishnah, the halakhic Midrash, the Talmud, and its commentaries. The Halakha has developed slowly, through a precedent-based system. The literature of questions to rabbis, and their considered answers, is referred to as responsa. Over time, as practices developed, codes of Jewish law were written based on the responsa. The most important code, the Shulkhan Arukh, largely determines Orthodox Jewish religious practice up to today.

Who is a Jew?

According to traditional Jewish law, someone is considered to be a Jew if he or she was born of a Jewish mother or converted in accord with Jewish Law. (Recently, the American Reform and Reconstructionist movements have included those born of Jewish fathers and Gentile mothers, if the children are raised as Jews.) However, most forms of Judaism today are open to sincere converts from any background.

Even in Orthodox tradition, a Jew who ceases to practice Judaism is still considered a Jew, as is a Jew who does not accept Jewish principles of faith and becomes an agnostic or an atheist; so too with a Jew who converts to another religion. However, in the latter case, the person loses standing as a member of the Jewish community and may become known as an apostate.

The question of what determines Jewish identity was given new impetus when, in the 1950s, David ben Gurion requested opinions on mihu Yehudi ("who is a Jew") from Jewish religious authorities and intellectuals worldwide. The question is far from settled and occasionally resurfaces in Israeli politics.

Jewish philosophy

Jewish philosophy refers to the conjunction between serious study of philosophy and Jewish theology. Early Jewish philosophy was influenced by the philosophy of Plato, Aristotle, and Islamic philosophy. Major Jewish philosophers include Solomon ibn Gabirol, Saadia Gaon, Maimonides, and Gersonides. Major changes occurred in response to the Enlightenment (late 1700s to early 1800s) leading to the post-Enlightenment Jewish philosophers, and then modern Jewish philosophers such as Martin Buber, Franz Rosenzweig, Mordecai Kaplan, Abraham Joshua Heschel, Will Herberg, Emmanuel Levinas, Richard Rubenstein, Emil Fackenheim, and Joseph Soloveitchik.

Jewish prayer and practice

Prayers

There are three main daily prayer services, named Shacharit, Mincha (literally: "flour-offering") and Maariv or Arvit. All services include a number of benedictions called the Amidah or the Shemonah Esrei ("eighteen"), which on weekdays consists of nineteen blessings (one was added in the time of the Mishna, but the name remains). Another key prayer in many services is the declaration of faith, the Shema which is recited at shacharit and maariv. Most of the prayers in a traditional Jewish service can be said in solitary prayer, but Kaddish and Kedusha require a group of ten adult men (or men and women in some branches of Judaism) called a minyan (prayer quorum). There are also prayers and benedictions recited throughout the day, such as those before eating or drinking.

There are a number of common Jewish religious objects used in prayer. The tallit is a Jewish prayer shawl. A kippah or yarmulke (skullcap) is a head covering worn during prayer by most Jews, and at all times by more orthodox Jews — especially Ashkenazim. Phylacteries or tefillin, boxes containing the portions of the Torah mandating them, are also worn by religious Jews during weekday morning services.

The Jewish approach to prayer differs among the various branches of Judaism. While all use the same set of prayers and texts, the frequency of prayer, the number of prayers recited at various religious events, and whether one prays in a particular liturgical language or the vernacular differs from denomination to denomination, with Conservative and Orthodox congregations using more traditional services, and Reform and Reconstructionist synagogues more likely to incorporate translations, contemporary writings, and abbreviated services.

Shabbat

Shabbat, the weekly day of rest lasting from Friday night to Saturday night, celebrates God's creation as a day of rest that commemorates God's day of rest upon the completion of creation. It plays an important role in Jewish practice and is the subject of a large body of religious law. Some consider it the most important Jewish holiday.

Jewish holidays

The Jewish holy days celebrate central themes in the relationship between God and the world, such as creation, revelation, and redemption. Some holidays are also linked to the agricultural cycle.

Three holidays celebrate revelation by commemorating different events in the passage of the Children of Israel out of slavery in Egypt to their return to the land of Canaan. They are also timed to coincide with important agricultural seasons. They are also pilgramage holidays, for which the Children of Israel would journey to Jerusalem to offer sacrifices to God in His Temple.

- Pesach or Passover celebrates the Exodus from Egypt, and coincides with the barley harvest. It is the only holiday that centers on home-service, the Seder. Pesach occurs on the 15th of Nisan; Nisan is the first month of the Jewish calendar, because it was in this month that the Children of Israel left Egypt.

- Shavuot or Pentacost or Feast of Weeks celebrates Moses' giving of the Ten Commandments to the Israelites, and marks the transition from the barley harvest to the wheat harvest.

- Sukkot, or "The Festival of Booths" commemorates the wandering of the Children of Israel through the desert. It is celebrated through the construction of temporary booths that represent the temporary shelters of the Children of Israel during their wandering. It coincides with the fruit harvest, and marks the end of the agricultural cycle.

- Rosh Hashanah, also Yom Ha-Zikkaron (The Day of Remembrance) or Yom Teruah (The Day of the Sounding of the Shofar). Called the Jewish New Year because it celebrates the day that the world was created, and marks the advance in the calendar from one year to the next, although it occurs in the seventh month, Tishri. It is also a holiday of redemption, as it marks the beginning of the atonement period that ends ten days later with Yom Kippur.

- Yom Kippur, or The Day of Atonement, also called "the Sabbath of Sabbaths," is a holiday centered on redemption; a day of atonement and fasting for sins committed during the previous year. Many consider this the most important Jewish holiday.

There are many minor holidays as well, including Purim, which celebrates the events told in the Biblical book of Esther, and Chanukkah, which is not established in the Bible but which celebrates the successful rebellion by the Maccabees against the Seleucid Empire.

Torah readings

The core of festival and Sabbath prayer services is the public reading of the Torah, along with connected readings from the other books of the Jewish Bible, called Haftarah. During the course of a year, the full Torah is read, and the cycle begins again every autumn during Simhat Torah (“rejoicing in the Torah”).

Synagogues and Jewish buildings

Synagogues are a Jewish houses of prayer and study, they usually contain separate rooms for prayer (the main sanctuary), smaller rooms for study, and often an area for community or educational use. There is no set blueprint for synagogues and the architectural shapes and interior designs of synagogues vary greatly, so a synagogue may contain any (or none) of these features:

- an ark (called aron ha-kodesh by Ashkenazim and hekhal by Sephardim) where the Torah scrolls are kept (the ark is often closed with an ornate curtain (parokhet) outside or inside the ark doors);

- a large elevated reader's platform (called bimah by Ashkenazim and tebah by Sephardim), where the Torah is read (and from where the services are conducted in Sephardi synagogues);

- an Eternal Light (ner tamid), a continually-lit lamp or lantern used as a reminder of the constantly lit menorah of the Temple in Jerusalem; and,

- (mainly in Ashkenazi synagogues) a pulpit facing the congregation to preach from and a pulpit or amud (Hebrew for "post" or "column") facing the Ark for the Hazzan (reader) to lead the prayers from.

In addition to synagogues, other buildings of signficance in Judaism include yeshivas, or institutions of Jewish learning, and mikvahs, which are ritual baths.

Dietary laws: Kashrut

The laws of kashrut ("keeping kosher") are the Jewish dietary laws. Food in accord with Jewish law is termed kosher, and food not in accord with Jewish law is termed treifah or treif. From the context of the laws in the book of Leviticus, the purpose of kashrut is related to ritual purity and holiness. Orthodox Jews and some Conservative Jews do keep kosher, to varying degrees of strictness, while Reform and Reconstructionist Jews generally do not.

Family purity

The laws of niddah ("menstruant", often referred to euphemistically as "family purity") and various other laws regulating the interaction between men and women (e.g., tzeniut, modesty in dress) are perceived, especially by Orthodox Jews, as vital factors in Jewish life, though they are rarely followed by Reform or Conservative Jews. The laws of niddah dictate that sexual intercourse cannot take place while the woman is having a menstrual flow, and she has to count seven "clean" days and immerse in a mikvah (ritual bath) following menstruation.

Life-cycle events

Life-cycle events occur throughout a Jew's life that bind him/her to the entire community.

- Brit milah - Welcoming male babies into the covenant through the rite of circumcision.

- Bar mitzvah and Bat mitzvah - Celebrating a child's reaching the age of majority, becoming responsible from now on for themselves as an adult for living a Jewish life and following halakha.

- Marriage

- Death and Mourning

Community leadership

Classical priesthood

Judaism does not have a clergy, in the sense of full-time specialists required for religious services. Technically, the last time Judaism had a clergy was prior to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E., when priests attended to the Temple and sacrifices. The priesthood is an inherited position, and although priests no longer have clerical duties, they are still honored in many Jewish communities.

- Kohen (priest) - patrilineal descendant of Aaron, brother of Moses. In the Temple, the kohanim were charged with performing the sacrifices. Today, a Kohen is the first one called up at the reading of the Torah, performs the priestly blessing, as well as complying with other unique laws.

- Levi (Levite) - Patrilineal descendant of Levi the son of Jacob. Today, a Levite is called up second to the reading of the Torah.

Prayer leaders

From the times of the Mishna and Talmud to the present, Judaism has required specialists or authorities for the practice of very few rituals or ceremonies. A Jew can fulfil most requirements for prayer by himself. Some activities — reading the Torah and haftarah (a supplementary portion from the Prophets or Writings); the prayer for mourners; the blessings for bridegroom and bride; the complete grace after meals — require a minyan, the presence of ten adults (Orthodox Jews and some Conservative Jews require ten adult men; some Conservative Jews and Reform Jews include women in the minyan).

The most common professional clergy in a synagogue are:

- Rabbi of a congregation - Jewish scholar who is charged with answering the legal questions of a congregation. Orthodox Judaism requires semicha (Rabbinical ordination). A congregation does not necessarily require a rabbi. Some congregations have a rabbi but also allow members of the congregation to act as shatz or baal koreh (see below).

- Hassidic Rebbe - rabbi who is the head of a Hassidic dynasty.

- Hazzan (cantor) - a trained vocalist who acts as shatz. Chosen for a good voice, knowledge of traditional tunes, understanding of the meaning of the prayers and sincerity in reciting them. A congregation does not need to have a dedicated hazzan.

Jewish prayer services do involve two specified roles, which are sometimes, but not always, filled by a rabbi and/or hazzan in many congregations:

- Shaliach tzibur or Shatz (leader — literally "agent" or "representative" — of the congregation) leads those assembled in prayer, and sometimes prays on behalf of the community. When a shatz recites a prayer on behalf of the congregation, he is not acting as an intermediary but rather as a facilitator. The entire congregation participates in the recital of such prayers by saying amen at their conclusion; it is with this act that the shatz's prayer becomes the prayer of the congregation. Any adult capable of speaking Hebrew clearly may act as shatz (Orthodox Jews and some Conservative Jews allow only men to act as shatz; some Conservative Jews and Reform Jews allow women to act as shatz as well).

- Baal koreh (master of the reading) reads the weekly Torah portion. The requirements for acting as baal koreh are the same as those for the shatz.

Note that these roles are not mutually exclusive. The same person is often qualified to fill more than one role, and often does.

Many congregations, especially larger ones, also rely on a:

- Gabbai (sexton) - Calls people up to the Torah, appoints the shatz for each prayer session if there is no standard shatz, and makes certain that the synagogue is kept clean and supplied.

The three preceding positions are usually voluntary and considered an honor. Since the Enlightenment large synagogues have often adopted the practice of hiring rabbis and hazzans to act as shatz and baal koreh, and this is still typically the case in most Conservative and Reform congregations. However, in most Orthodox synagogues these positions are filled by laypeople.

Specialized religious roles

- Dayan (judge) - expert in Jewish law who sits on a beth din (rabbinical court) for either monetary matters or for overseeing the giving of a bill of divorce (get). A dayan always requires semicha.

- Mohel - performs the brit milah (circumcision). An expert in the laws of circumcision who has received training from a qualified mohel.

- Shochet (ritual slaughterer) - slaughters all kosher meat. In order for meat to be kosher, it must be slaughtered by a shochet who is expert in the laws and has received training from another shochet, as well as having regular contact with a rabbi and revising the relevant guidelines on a regular basis.

- Sofer (scribe) - Torah scrolls, tefillin (phylacteries), mezuzahs (scrolls put on doorposts), and gittin (bills of divorce) must be written by a sofer who is an expert in the laws of writing.

- Rosh yeshivah - head of a yeshiva. Somebody who is an expert in delving into the depths of the Talmud, and lectures the highest class in a yeshiva.

- Mashgiach of a yeshiva - expert in mussar (ethics). Oversees the emotional and spiritual welfare of the students in a yeshiva, and gives lectures on mussar.

- Mashgiach over kosher products - supervises merchants and manufacturers of kosher food to ensure that the food is kosher. Either an expert in the laws of kashrut, or (generally) under the supervision of a rabbi who is expert in those laws.

Jewish religious history

Jewish history is an extensive topic; this section will cover the elements of Jewish history of most importance to the Jewish religion and the development of Jewish denominations.

Ancient Jewish religious history

Jews trace their religious lineage to the biblical patriarch Abraham through Isaac and Jacob. After the Exodus from Egypt, the Jews came to Canaan, and settled the land. A kingdom was established under Saul and continued under King David and Solomon with its capital in Jerusalem. After Solomon's reign the nation split into two kingdoms, the Kingdom of Israel (in the north) and the Kingdom of Judah (in the south). The Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Assyrian ruler Shalmaneser V in the 8th century B.C.E. and spread all over the Assyrian empire, where they were assimilated into other cultures and become known as the Ten Lost Tribes. The Kingdom of Judah continued as an independent state until it was conquered by a Babylonian army in the early 6th century B.C.E., destroying the First Temple that was at the centre of ancient Jewish worship. The Judean elite was exiled to Babylonia, but later at least a part of them returned to their homeland after the subsequent conquest of Babylonia by the Persians seventy years later, a period known as the Babylonian Captivity. A new Second Temple was constructed, and old religious practices were resumed.

After a Jewish revolt against Roman rule in 66 C.E., the Romans all but destroyed Jerusalem; only a single "Western Wall" of the Second Temple remained. Following a second revolt, Jews were not allowed to enter the city of Jerusalem and most Jewish worship was forbidden by Rome. Following the destruction of Jerusalem and the expulsion of the Jews, Jewish worship stopped being centrally organized around the Temple, and instead was rebuilt around rabbis who acted as teachers and leaders of individual communities (see Jewish diaspora). No new books were added to the Jewish Bible after the Roman period, instead major efforts went into interpreting and developing Jewish law.

Historical Jewish groupings (to 1700)

Around the first century CE there were several small Jewish sects: the Pharisees, Sadducees, Zealots, Essenes, and Christians. After the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E., these sects vanished. Christianity survived, but by breaking with Judaism and becoming a separate religion; the Pharisees survived but in the form of Rabbinic Judaism (today, known simply as "Judaism").

Some Jews in the 8th and 9th centuries adopted the Sadducees' rejection of the oral law of the Pharisees/rabbis recorded in the Mishnah (and developed by later rabbis in the two Talmuds), intending to rely only upon the Tanakh. These included the Isunians, the Yudganites, the Malikites, and others. They soon developed oral traditions of their own which differed from the rabbinic traditions, and eventually formed the Karaite sect. Karaites exist in small numbers today, mostly living in Israel. Rabbinical and Karaite Jews each hold that the others are Jews, but that the other faith is erroneous.

Over time Jews developed into distinct ethnic groups — amongst others, the Ashkenazi Jews (of Central and Eastern Europe with Russia); the Sephardi Jews (of Spain, Portugal, and North Africa) and the Yemenite Jews, from the southern tip of the Arabian peninsula. This split is cultural, and is not based on any doctrinal dispute, although the distance did result in minor differences in practice and prayers.

Hasidism

Hasidic Judaism was founded by Israel ben Eliezer (1700-1760), also known as the Ba'al Shem Tov (or Besht). His disciples attracted many followers; they themselves established numerous Hasidic sects across Europe. Hasidic Judaism eventually became the way of life for many Jews in Europe. Waves of Jewish immigration in the 1880s carried it to the United States.

Early on, there was a serious schism between Hasidic and non-Hasidic Jews. European Jews who rejected the Hasidic movement were dubbed by the Hasidim as mitnagdim, (lit. "opponents"). Some of the reasons for the rejection of Hasidic Judaism were the overwhelming exuberance of Hasidic worship; their untraditional ascriptions of infallibility and alleged miracle-working to their leaders, and the concern that it might become a messianic sect. Since then all the sects of Hasidic Judaism have been subsumed into mainstream Orthodox Judaism, particularly Haredi Judaism.

The Enlightenment and Reform Judaism

In the late 18th century CE Europe was swept by a group of intellectual, social and political movements known as the Enlightenment. The Enlightenment led to reductions in the European laws that prohibited Jews to interact with the wider secular world, thus allowing Jews access to secular education and experience. A parallel Jewish movement, Haskalah or the "Jewish Enlightenment," began, especially in Central Europe, in response to both the Enlightenment and these new freedoms. It placed an emphasis on integration with secular society and a pursuit of non-religious knowledge. The thrust and counter-thrust between supporters of Haskalah and more traditional Jewish concepts eventually led to the formation of a number of different branches of Judaism: Haskalah supporters founded Reform Judaism and Liberal Judaism, while traditionalists founded many forms of Orthodox Judaism, and Jews seeking a balance between the two sides founded Conservative Judaism. A number of smaller groups came into being as well.

The Holocaust

While the Holocaust did not immediately affect Jewish denominations, its great loss of life caused a radical demographic shift, ultimately affecting the makeup of organized Judaism the way it is today. A Jewish day of mourning, Yom HaShoah, was inserted into the Jewish calendar, commemorating the Holocaust.

The present situation

In most Western nations, such as the United States of America, Israel, Canada, United Kingdom and South Africa, a wide variety of Jewish practices exist, along with a growing plurality of secular and non-practicing Jews. For example, in the world's largest Jewish community, the United States, according to the 2001 National Jewish Population Survey, 4.3 million out of 5.1 million Jews had some sort of connection to the religion. Of that population of connected Jews, 80% participated in some sort of Jewish religious observance, but only 48% belonged to a synagogue.

Religious (and secular) Jewish movements in the USA and Canada perceive this as a crisis situation, and have grave concern over rising rates of intermarriage and assimilation in the Jewish community. Since American Jews are marrying at a later time in their life than they used to, and are having fewer children than they used, the birth rate for American Jews has dropped from over 2.0 down to 1.7 (the replacement rate is 2.1). (This is My Beloved, This is My Friend: A Rabbinic Letter on Intimate relations, p. 27, Elliot N. Dorff, The Rabbinical Assembly, 1996). Intermarriage rates range from 40-50% in the US, and only about a third of children of intermarried couples are raised Jewish. Due to intermarriage and low birth rates, the Jewish population in the US shrank from 5.5 million in 1990 to 5.1 million in 2001. This is indicative of the general population trends among the Jewish community in the Diaspora, but a focus on population masks the diversity of current Jewish religious practice, as well as growth trends among some communities, like haredi Jews.

In the last 50 years there has been a general increase in interest in religion among many segments of the Jewish population. All of the major Jewish denominations have experienced a resurgence in popularity, with increasing numbers of younger Jews participating in Jewish education, joining synagogues, and becoming (to varying degrees) more observant. Complementing the increased popularity of the major denominations has been a number of new approaches to Jewish worship, including feminist approaches to Judaism and Jewish renewal movements. There is a separate article on the Baal teshuva movement, the movement of Jews returning to observant Judaism. Though this gain has not offset the general demographic loss due to intermarriage and acculturation, many Jewish communities and movements are growing.

Judaism and other religions

Christianity and Judaism

There are a number of articles on the relationship between Judaism and Christianity. These articles include:

- Comparing and contrasting Judaism and Christianity

- Judeo-Christian

- Christianity and anti-Semitism

- Jewish view of Jesus

- Cultural and historical background of Jesus

Since the Holocaust, there has been much to note in the way of reconciliation between some Christian groups and the Jewish people; the article on Christian-Jewish reconciliation studies this issue.

Messianic Judaism (sometimes Hebrew Christianity) is the common designation for a number of Christian groups which include varying degrees of Jewish practice. These groups have attracted tens (and perhaps hundreds) of thousands of Jews and Christians to their ranks; members identify themselves as Jews. These groups are viewed highly negatively by all Jewish denominations, which typically see them as covert and deceptive attempts to convert Jews to Christianity, a view Messianic-Jewish groups strongly contest.

Mormonism and Judaism

If a member of the Latter Day Saints church has an established Jewish heritage and lineage, then they are considered by the Mormons to be of the Tribe of Judah, and as such, considered both Mormon and Jewish by Mormon authorities, though not in Jewish practice.

Islam and Judaism

Under Islamic rule, Judaism has been practiced for almost 1500 years and this has led to an interplay between the two religions which has been positive as well as negative at times. The period around 900 to 1200 in Moorish Spain came to be known as the Golden age of Jewish culture in Spain.

The 20th century animosity of Muslim leaders towards Zionism, the political movement of Jewish self-determination, has led to a renewed interest in the relationship between Judaism and Islam.

Other relevant material:

- Muslim Jew

- Similarities between the Bible and the Qur'an

- Islam and anti-Semitism

See also

Jews and Judaism

- Jew for information on Jews from a national, ethnic, and cultural perspective.

- Jewish history

- Jewish population

- Judaism by country

- Anti-Semitism

- Israel

- Secular Jewish culture

- Jewish humour

- List of converts to Judaism

- Zionism

Jewish law and religion

- Halakha (religious law)

- Who is a Jew?

- Jewish ethics

- Jewish views of homosexuality

- Jewish ethics and Mussar Movement concern the ethical teachings of Judaism.

- Holocaust theology

- Torah

- Rabbinic literature, including the Talmud

- Jewish services

- List of Jewish prayers and blessings

- Jewish eschatology, Jewish views of the Messiah and the afterlife.

- Role of women in Judaism

Comparative

- Abrahamic religions

- Jewish views of religious pluralism

- List of religions

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ancient Judaism, Max Weber, Free Press, 1967, ISBN 0029341302

- Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition and Practice Wayne Dosick.

- Conservative Judaism: The New Century, Neil Gillman, Behrman House.

- American Jewish Orthodoxy in Historical Perspective Jeffrey S. Gurock, 1996, Ktav.

- Philosophies of Judaism Julius Guttmann, trans. by David Silverman, JPS. 1964

- Back to the Sources: Reading the Classic Jewish Texts Ed. Barry W. Holtz, Summit Books

- A History of the Jews Paul Johnson, HarperCollins, 1988

- A People Divided: Judaism in Contemporary America, Jack Wertheimer. Brandeis Univ. Press, 1997.

- Encyclopaedia Judaica, Keter Publishing, CD-ROM edition, 1997

- The American Jewish Identity Survey, article by Egon Mayer, Barry Kosmin and Ariela Keysar; a sub-set of The American Religious Identity Survey, City University of New York Graduate Center. An article on this survey is printed in The New York Jewish Week, November 2, 2001.

External links

General

- Judaism 101, an extensive FAQ written by a librarian.

- Microsoft Encarta article on Judaism

- Judaism article from the 1901-1906 Jewish Encyclopedia

- Extensive Collection of Links, from Shamash.org

- Introduction to Judaism from About.com.

- Judaism from ReligionFacts.com.

- Jewish Concepts from the Jewish Virtual Library.

Orthodox/Modern Orthodox/Hasidic

- Orthodox Judaism - The Orthodox Union: Official website

- Chabad-Lubavitch: Official website

- What is Orthodox Judaism? Frequently Asked Questions and Answers

- The Various Types of Orthodox Judaism

- The State of Orthodox Judaism Today

Conservative

- The United Synagogues of Conservative Judaism: Official website

- Introduction to Conservative Judaism

- The State of Conservative Judaism Today

Reform

- Reform Judaism (UK): Official website

- Reform Judaism (USA): Official website

- The Origin of Reform Judaism

- What is Reform Judaism? Frequently Asked Questions and Answers

- Jewish Virtual Library articles on Reform Judaism

Reconstructionist

Humanistic

Karaite

Jewish religious literature and texts

- Wikisource Pentateuch (in Hebrew).

- Complete Tanakh (in Hebrew, with vowels).

- English Tanakh from the 1917 Jewish Publication Society version.

- Torah.org - The Judaism Site. (also known as Project Genesis) Contains Torah commentaries and studies of Tanakh, along with Jewish ethics, philosophy, holidays and other classes.

- The complete formatted Talmud online. Interpretative videos for each page from a Orthodox viewpoint are provided in French, English, Yiddish and Hebrew.

- Links to many sources of Divrei Torah. Interpretations and discussions of portions of the Tanach from many different viewpoints.

Wikimedia Torah study projects

Text study projects at Wikisource. In many instances, the Hebrew versions of these projects are more fully developed than the English.

- Mikraot Gedolot (Rabbinic Bible) in Hebrew (sample) and English (sample).

- Cantillation at the "Vayavinu Bamikra" Project in Hebrew (lists nearly 200 recordings) and English.

- Mishnah in Hebrew (sample) and English (sample).

- Shulchan Aruch in Hebrew and English (Hebrew text with English translation).

af:Judaïsme ar:يهودية zh-min-nan:Iu-thài-kàu bg:Юдаизъм bn:ইহুদীধর্ম ca:Judaisme da:Jødedom de:Judentum et:Judaism es:Judaísmo eo:Judismo fa:یهودیت fr:Judaïsme he:יהדות id:Agama Yahudi it:Giudaismo kw:Yedhoweth la:Religio Iudaica lv:Jūdaisms lt:Judaizmas ms:Yahudi nl:Jodendom ja:ユダヤ教 ko:유대교 no:Jødedom nn:Jødedommen pl:Judaizm pt:Judaísmo ro:Iudaism ru:Иудаизм simple:Judaism sl:Judovstvo sr:Јудаизам fi:Juutalaisuus sv:Judendom tl:Hudaismo th:ยูได tr:Musevilik tt:Yähüd dine yi:ייִדישקײט zh-cn:犹太教

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.