Abrahamic religions

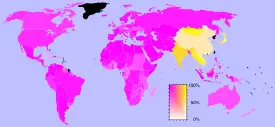

The Abrahamic religions refer to three sister monotheistic religions (Judaism, Christianity, and Islam) that claim the prophet Abraham (Hebrew: Avraham אַבְרָהָם ; Arabic: Ibrahim ابراهيم ) as their common forefather. These religions account for more than half of the world's total population today.[1]

The Prophet Abraham is claimed by Jews as the ancestor of the Israelites, while his son Ishmael (Isma'il) is seen in Muslim tradition as the ancestor of the Arabs. In Christian tradition, Abraham is described as a "father in faith" (see Romans 4), which may suggest that all three religions come from one source.

In modern times, leaders from all three Abrahamic faiths have begun to interact and engage in constructive Inter-religious Dialogue. They have begun to acknowledge their shared spiritual riches to help overcome the pains and prejudices of past eras and move forward to building a world of religious co-operation.

Other religious categories used to group the world's religions include the Dharmic religions, and the Chinese religions of East Asia.

Origin of the expression

The expression 'Abrahamic religions' originates from the Qur'an's repeated references to the 'religion of Abraham' (see Surahs 2:130,135; 3:95; 6:123,161; 12:38; 16:123; 22:78). In particular, this expression refers specifically to Islam, and is sometimes contrasted to Judaism and Christianity, as for example in Surah 2:135: "They say: "Become Jews or Christians if ye would be guided (To salvation)." Say thou: "Nay! (I would rather) the Religion of Abraham the True, and he joined not gods with God." In the Qur'an, Abraham is declared to have been a Muslim, 'not a Jew nor a Christian' (Surah 3:67). The latter assertion is made on the basis that Prophet Muhammad's divine revelation is considered to be a continuation of the previous Prophets' revelations from God, hence they are all believed to be Muslims. However, the expression 'Abrahamic religions' is generally used to imply that all of the three faiths share a common heritage.

Adam, Noah, and Moses are also common to all three religions. As for why we do not speak of an "Adamic," "Noachian," or "Mosaic" family, this may be for fear of confusion. Adam and Noah are said to be the ancestors of all humanity (though as named characters they are specific to the Biblical/Qur'anic tradition). Moses is closely associated with Judaism and, through Judaism, continuing into Christianity; Moses is regarded as a Prophet in Islam, but the term "Mosaic" may imply a genealogical lineage that the first Muslims—being Arab—did not share (e.g., descending from Ishmael). Thus, the scope suggested by the first two terms is larger than intended, while the third is too small.

Patriarchs

There are six notable figures in the Bible prior to Abraham: Adam and Eve, their two sons Cain and Abel, Enoch, and his great-grandson, Noah, who, according to the story, saved his own family and all animal life in Noah's Ark. It is uncertain whether any of them (assuming they existed) left any recorded moral code: some Christian churches maintain faith in ancient books like the Book of Enoch—and Genesis mentions the Noahide Laws given by God to the family of Noah. For the most part, these 'patriarchs' serve as good (or bad, in the case of Cain) role models of behavior, without a more specific indication of how one interprets their actions in any religion.

In the Book of Genesis, Abraham is specifically instructed to leave Ur of the Chaldees so that God will "make of you a great nation."

According to the Bible, the patriarch Abraham (or Ibrahim, in Arabic) had eight sons by three wives: one (Ishmael) by his wife's servant Hagar, one (Isaac) by his wife Sarah, and six by another wife Keturah. Moses, Jesus, Muhammad, Bahá'u'lláh and other prominent figures are all claimed to be descendants of Abraham through one of these sons.

Jews see Abraham as the progenitor of the people of Israel, through his descendants Isaac and Jacob. Christians view Abraham as an important exemplar of faith, and a spiritual, as well as a physical, ancestor of Jesus. In addition, Muslims refer to Sabians, Christians and Jews as "People of the Book" ("the Book" referring to the Tanakh, the New Testament, and the Qur'an). They see Abraham as one of the most important of the many prophets sent by God. Thus, Abraham represents for some, a point of commonality that they seek to emphasize by means of this terminology.

The significance of Abraham

- For Jews, Abraham is primarily a revered ancestor or Patriarch (referred to as "Our Father Abraham") to whom God made several promises: that he would have numberless descendants, and that they would receive the land of Canaan (the "Promised Land"). Abraham is also known as the first post-flood person to reject idolatry through rational analysis. (Shem and Eber carried on the Tradition from Noah), hence he symbolically appears as a fundamental figure for monotheistic religion.

- For Christians, Abraham is a spiritual forebear rather than a direct ancestor.[2] For example, Christian iconography depicts him as an early witness to the Trinity in the form of three "angels" who visited him (the Hospitality of Abraham). In Christian belief, Abraham is a model of faith,[3] and his intention to obey God by offering up Isaac is seen as a foreshadowing of God's offering of his son, Jesus.[4] A longstanding tendency of Christian commentators is to interpret God's promises to Abraham, as applying to Christianity (the "True Israel") rather than Judaism (whose representatives rejected Christ).

- In Islam, Ibrahim is considered part of a line of prophets beginning with Adam (Genesis 20:7 also calls him a "prophet"), as well as the "first Muslim" – i.e., the first monotheist in a world where monotheism was lost. He is also referred to as ابونة ابرهيم or "Our Father Abraham," as well as Ibrahim al-Hanif or Abraham the Monotheist. Islam holds that it was Ishmael (Isma'il) rather than Isaac whom Ibrahim was instructed to sacrifice.

All the Abrahamic religions are related to Judaism as practiced in ancient kingdoms of Israel and Judah prior to the Babylonian Exile, at the beginning of the first millennium B.C.E.

A number of significant commonalities are shared among Judaism, Christianity, and Islam:

- Monotheism. All three religions worship one God, although Jews and Muslims sometimes criticize the common Christian doctrine of the Holy Trinity as polytheistic. Indeed, there exists among their followers a general understanding that they worship the same one God.

- A prophetic tradition. All three religions recognize figures called "prophets," though their lists differ, as do their interpretations of the prophetic role.

- Semitic origins. Judaism and Islam originated among Semitic peoples – namely the Jews and Arabs, respectively – while Christianity arose out of Judaism.

- A basis in divine revelation rather than, for example, philosophical speculation or custom.

- An ethical orientation. All three religions speak of a choice between good and evil, which is conflated with obedience or disobedience to God.

- A linear concept of history, beginning with the Creation and the concept that God works through history.

- Association with the desert, which some commentators believe has imbued these religions with a particular ethos.

- Devotion to the traditions found in the Bible and the Qur'an, such as the stories of Adam, Noah, Abraham, and Moses.

Monotheism

Judaism and Islam worship a Supreme Deity which they conceive strictly monotheistically as one being; Christianity agrees, but the Christian God is at the same time (according to most of mainstream Christianity) an indivisible Trinity, a view not shared by the other religions. A sizable minority of Christians and Christian denominations do not support the belief in the doctrine of the Trinity, and sometimes suggest that the Trinity idea was founded in Roman religious culture, specifically suggesting that it was formulated due to Rome's absorption of some Zoroastrian and some Pagan ideology as part of their homogenized culture, and was not part of the original, primitive Christianity.

This Supreme Being is referred to in the Hebrew Bible in several ways, such as Elohim, Adonai or by the four Hebrew letters "Y-H-V (or W) -H" (the tetragrammaton), which observant Jews do not pronounce as a word. The Hebrew words Eloheynu (Our God) and HaShem (The Name), as well as the English names "Lord" and "God," are also used in modern day Judaism. The latter is sometimes written "G-d" in reference to the taboo against pronouncing the tetragrammaton.

Allah is the standard Arabic translation for the word "God." Islamic tradition also describes the 99 names of God. Muslims believe that the Jewish God is the same as their God and that Jesus is a divinely inspired prophet, but not God. Thus, both the Torah and the Gospels are believed to be based upon divine revelation, but Muslims believe them to have been corrupted (both accidentally through errors in transmission and intentionally by Jews and Christians over the centuries). Muslims revere the Qur'an as the final uncorrupted word of God or the last testament brought through the last prophet, Muhammad. Muhammad is regarded as the "Seal of the Prophets" and Islam is viewed as the final monotheist faith for all of humanity.

Religious scriptures (People of the Book)

All three Abrahamic religions rely on a body of scriptures, some of which are considered to be the word of God — hence sacred and unquestionable — and some the work of religious men, revered mainly by tradition and to the extent that they are considered to have been divinely inspired, if not dictated, by the divine being.

The sacred scriptures of Judaism are comprised of the Tanakh, a Hebrew acronym that stands for Torah (Law or Teachings), Nevi'im (Prophets), and Ketuvim (Writings). These are complemented by and supplemented with various originally oral traditions: Midrash, the Mishnah, the Talmud, and collected rabbinical writings. The Hebrew text of the Tanakh, and the Torah in particular, is considered holy.

The sacred scripture of Christians is the Holy Bible, which comprises of both the Old and New Testaments. This corpus is usually considered to be divinely inspired. Christians believe that the coming of Jesus as the Messiah and savior of humankind would shed light on the true relationship between God and humanity by restoring the emphasis of universal love and compassion (as mentioned in the Shema) above the other commandments, and de-emphasising the more "legalistic" and material precepts of Mosaic Law (such as the dietary constraints and temple rites). Some Christians believe that the link between Old and New Testaments in the Bible means that Judaism has been superseded by Christianity as the "new Israel," and that Jesus' teachings described Israel not as a geographic place but as an association with God and promise of salvation in heaven.

Islam's holiest book is the Qur'an, comprised of 114 surahs ("chapters of the Qur'an"). However, Muslims also believe in the religious texts of Judaism and Christianity in their original forms and not the current versions, which they believe to be corrupted. According to the Qur'an (and mainstream Muslim belief) the verses of the Qur'an were revealed from All through the Archangel Gabriel to the Prophet Muhammad on separate occasions. These revelations were written down during Muhammad's lifetime and collected into one official copy in 633 C.E., one year after his death. Finally, the Qur'an was given its present order in 653 C.E. by the third Caliph (Uthman ibn Affan).

The Qur'an mentions and reveres several of the Israelite Prophets, including Jesus, amongst others. The stories of these Prophets are very similar to those in the Bible. However, the detailed precepts of the Tanakh and the New Testament are not adopted outright; they are replaced by the new commandments revealed directly by God (through Gabriel) to Muhammad and codified in the Qur'an.

The Muslims consider the original Arabic text of the Qur'an as uncorrupted and holy to the last letter, and any translations are considered to be interpretations of the meaning of the Qur'an, as only the original Arabic text is considered to be the divine scripture.

The Qur'an is complemented by the Hadith, a set of books by later authors that record the sayings of the Prophet Muhammad. The Hadith interpret and elaborate Qur'anic precepts. There is no consensus within Islam on the authority of the Hadith collections, but Islamic scholars have categorized each Hadith at one of the following levels of authenticity or isnad: genuine (sahih), fair (hasan), or weak (da'if). Amongst Shia Muslims, no hadith is regarded as Sahih, and hadith in general are only accepted if there is no disagreement with the Qur'an.

Eschatology

The Abrahamic religions also share an expectation of an individual who will herald the end time (Greek: eschaton), and/or bring about the Kingdom of God on Earth, in other words the fulfillment of Messianic prophecy. Judaism awaits the coming of the Jewish Messiah (the Jewish concept of Messiah differs from the Christian concept in several significant ways). Christianity awaits the Second Coming of Christ. Islam awaits both the second coming of Jesus (in order to complete his life and die, since he is said to have been risen alive and not crucified) and the coming of Mahdi (Sunnis in his first incarnation, Shi'as the return of Muhammad al-Mahdi). The Ahmadiyya Muslim Community believes that both Mahdi and Second Coming of Christ were fulfilled in Mirza Ghulam Ahmad.

Afterlife

The Abrahamic religions (in most of their branches) agree that a human being comprises the body, which dies, and the soul, which need not do so. The soul, capable of remaining alive beyond human death, carries the essence of that person with it, and God will judge that person's life accordingly after they die. The importance of this, the focus on it, and the precise criteria and end result differs between religions.

Reincarnation and transmigration tend not to feature prominently in Abrahamic religions. Although as a rule they all look to some form of afterlife, Christianity and Islam support a continuation of life, usually viewed as eternal, rather than reincarnation and transmigration which are a return (or repeated returns) to this Earth or some other plane to live a complete new life cycle over again. Kabbalic Judaism, however, accepts the concept of returning in new births through a process called "gilgul neshamot," but this is not Torah-derived, and is usually studied only among scholars and mystics within the faith.

Judaism's views on the afterlife ("the World to Come") are quite diverse and its discussion is not encouraged. This can be attributed to the fact that even though there clearly are traditions in the Hebrew Bible of an afterlife, Judaism focuses on this life and how to lead a holy life to please God, rather than future reward, and its attitude can be mostly summed up by the rabbinical observation that at the start of Genesis God clothed the naked (Adam and Eve), at the end of Deuteronomy He buried the dead (Moses), the Children of Israel mourned for 40 days, then got on with their lives. If there is an afterlife all agree in Judaism that the good of all the nations will get to heaven and this is one of the reasons Judaism does not normally proselytize.

In Islam, God is said to be "Most Compassionate and Most Merciful" (Qur'an 1:1). However God is also "Most Just," Islam prescribes a literal Hell for those who disobey God and commit gross sin. Those who obey God and submit to God will be rewarded with their own place in Paradise. While sinners are punished with fire, there are also many other forms of punishment described, depending on the sin committed; Hell is divided into numerous levels, an idea that found its way into Christian literature through Dante's borrowing of Muslim themes and tropes for his Inferno.

Those who worship and remember God are promised eternal abode in a physical and spiritual Paradise. In Islam, Heaven is divided into numerous levels, with the higher levels of Paradise being the reward of those who have been more virtuous. For example, the highest levels might contain the Prophets, those killed for believing, those who help orphans, and those who never tell a lie (among numerous other categories cited in the Qur'an and Hadith).

Upon repentance to God, many sins can be forgiven as God is said to be the most Merciful. Additionally, those who ultimately believe in God, but have led sinful lives, may be punished for a time, and then ultimately released into Paradise. If anyone dies in a state of Shirk (the association God in any way, such as claiming that He is equal with anything or worshiping other than Him), then it is possible he will stay forever in Hell; however, it is said that anyone with "one atom of faith" will eventually reach Heaven, and Muslim literature also records reference to even the greatly sinful, Muslim and otherwise, eventually being pardoned and released into Paradise.

According to Islam, once a person is admitted to Paradise, this person will abide there for eternity.

Worship

Worship, ceremonies, and religion-related customs differ substantially between the various Abrahamic religions. Among the few similarities are a seven-day cycle in which one day is nominally reserved for worship, prayer, or other religious activities; this custom is related to the Biblical story of Genesis, where God created the universe in six days, and rested in the seventh. Islam, which has Friday as a day for special congregational prayers, does not subscribe to the 'resting day' concept.

Jewish men are required to pray three times daily and four times daily on the Sabbath and most Jewish holidays, and five times on Yom Kippur. Before the destruction of the Temple, Jewish priests offered sacrifices there; afterwards, the practice was stopped. Jewish women's prayer obligations vary by sect; traditionally (according to Torah Judaism), women do not read from the Torah and are only required to say certain parts of these services twice daily. Conservative Judaism, Reform Judaism, and the Reconstructionist movement have different views.

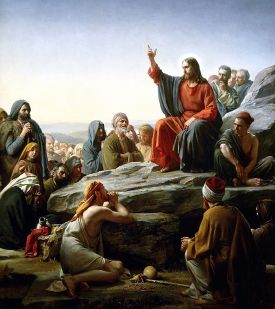

Christianity does not have any sacrificial rites as such, but its entire theology is based upon the concept of the sacrifice by God of his son Jesus so that his blood might atone for humankind's sins. However, offerings to Christian Churches and charity to poor are highly encouraged and take the place of sacrifice. Additionally, self-sacrifice in the form of Lent, penitence and humbleness, in the name of Christ and according to his commandments (cf. Sermon on the Mount), is considered a form of sacrifice that appeals God.

The followers of Islam, Muslims, are to observe the Five Pillars of Islam. The first pillar is the belief in the oneness of Allah (God) and in Muhammad as his final prophet. The second is to pray five times daily (salat) towards the direction (qibla) of the Kaaba in Mecca. The third pillar is Zakah, is a portion of one’s wealth that must be given to the poor or to other specified causes, which means the giving of a specific share of one’s wealth and savings to persons or causes that God mentions in the Qur’an. The normal share to be paid is two and a half percent of one’s saved earnings. Fasting during the Muslim month of Ramadan is the fourth pillar of Islam, to which only able-bodied Muslims are required to fast. Finally, Muslims are also urged to undertake a pilgrimage to Mecca at least once in one's life. Only individuals whose financial position and health are insufficient are exempt from making Hajj. During this pilgrimage, the Muslims spend several days in worship, repenting and most notably, circumambulating the Kaaba among millions of other Muslims. At the end of the Hajj, sheep and other permissible animals are slaughtered to commemorate the moment when God replaced Abraham's son, Ishmael with a sheep preventing his sacrifice. The meat from these animals is then distributed around the world to needy Muslims, neighbors and relatives.

Circumcision

Both Judaism and Islam prescribe circumcision for males as a symbol of dedication to the religion. Islam also recommends this practice as a form of cleanliness. Western Christianity replaced that custom by a baptism ceremony that varies according to the denomination, but generally includes immersion, aspersion or anointment with water. As a result of the decision of the Early Church (Acts 15, the Council of Jerusalem) that circumcision is not mandatory, it continues to be optional, though the Council of Florence[5] prohibited it and paragraph #2297 of the Catholic Catechism calls non-medical amputation or mutilation immoral.[6] Many countries with majorities of Christian adherents have low circumcision rates (with the notable exception of the United States[7] and the Philippines). However, many males in Coptic Christianity and Ethiopian Orthodoxy still observe circumcision.

Food restrictions

Judaism and Islam have strict dietary laws, with lawful food being called kosher in Judaism and halaal in Islam. Both religions prohibit the consumption of pork; Islam also prohibits the consumption of alcoholic beverages of any kind. Halaal restrictions can be seen as a subset of the kashrut dietary laws, so many kosher foods are considered halaal; especially in the case of meat, which Islam prescribes must be slaughtered in the name of God. Protestants have no set food laws. Roman Catholicism however developed ritual prohibitions against the consumption of meat (but not fish) on Fridays, and the Christian calendars prescribe abstinence from some foods at various times of the year; but these customs vary from place to place, and have changed over time, and some sects have nothing comparable. Some Christians oppose the consumption of alcoholic beverages, while a few Christians also follow a kosher diet, sometimes identified as a "What Would Jesus Eat?" diet. Some approaches to practice have developed in Protestant denominations, such as the Seventh-day Adventist Church, which strongly advise against certain foods and in some cases encourage vegetarianism or veganism.

Proselytism

Christianity encourages evangelism in an attempt to convince others to convert to the religion; many Christian organizations, especially Protestant churches, send missionaries to non-Christian communities throughout the world.

Forced conversions to Christianity have been documented at various points throughout history. The most prominently cited allegations are the conversions of the pagans after Constantine; of Muslims, Jews and Eastern Orthodox during the Crusades; of Jews and Muslims during the time of the Spanish Inquisition where they were offered the choice exile, conversion or death; and of the Aztecs by Hernan Cortes. Forced conversions are condemned as sinful by major denominations such as the Roman Catholic Church, which officially state that forced conversions pollute the Christian religion and offend human dignity, so that past or present offenses are regarded as a scandal (a cause of unbelief).[8]

"It is one of the major tenets of Catholic doctrine that man's response to God in faith must be free: no one therefore is to be forced to embrace the Christian faith against his own will."

William Heffening states that in the Qur'an "the apostate is threatened with punishment in the next world only" however "in traditions, there is little echo of these punishments in the next world … and instead, we have in many traditions a new element, the death penalty."[9] Heffening states that Shafi'is interpret verse 2:217 as adducing the main evidence for the death penalty in the Qur'an.[10] The Qur'an has a chapter (Sura) dealing with non believers (called "Al-Kafiroon").[11] In the chapter there is also an often quoted verse (ayat) which reads, "There is no compulsion in religion, the path of guidance stands out clear from error" [2:256] and [60:8]. This means that no one is to be compelled into Islam and that the righteous path is distinct from the rest. According to this verse, converts to Islam are ones that see this path. The Muslim expansion during the Ummayad dynasty held true to this teaching, affording second-class citizenship to "People of the Book" instead of forced conversion. Nevertheless, it should be noted that pagan Arab tribes were given the choice of 'Islam or Jizya (defense tax) or War.'[12] Another notable exception is the en masse forced conversion of the Jews of Mashhad in 1839.[13] In the present day, Islam does not have missionaries comparable to Christianity, though it does encourage its followers to learn about other religions and to teach others about Islam.

While Judaism accepts converts, it does not encourage them, and has no missionaries as such. Only a few forced conversions to Judaism have been recorded for example the Idumeans, were forced into conversion to Judaism by the Hasmonean kings. However Judaism states that non-Jews can achieve righteousness by following Noahide Laws, a set of seven universal commandments that non-Jews are expected to follow. In this context the Rambam (Rabbi Moses Maimonides, one of the major Jewish teachers) commented, "Quoting from our sages, the righteous people from other nations have a place in the world to come, if they have acquired what they should learn about the Creator." As the commandments applicable to the Jews are much more detailed and onerous than Noahide Laws, Jewish scholars have traditionally maintained that it is better to be a good non-Jew than a bad Jew, thus discouraging conversion. Most often, converts to Judaism are those who marry Jews.

Notes

- ↑ Major Religions of the World Ranked by Number of Adherents Adherents.com. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ↑ Romans 4:9-12.

- ↑ Hebrews 11:8-10.

- ↑ John MacArthur, The MacArthur New Testament Commentary: Romans (Chicago: Moody Press, 1996), 505.

- ↑ Papal bull, Ecumenical Council of Florence (1438-1445) The Circumcision Reference Library. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ↑ Father John Dietzen, The Morality of Circumcision The Circumcision Reference Library. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ↑ Mary G. Ray, 82% of the World’s Men are Intact Mothers Against Circumcision, 1997. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ↑ Pope Paul VI, Declaration on Religious Freedom, December 7, 1965. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ↑ W. Heffening, Encyclopedia of Islam (Brill, 1993, ISBN 978-9004097964).

- ↑ Qur'an 2:17 Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ↑ Qur'an 109. Retrieved March 16, 2018.

- ↑ Montgomery Watt, "A Historical Overview" in Introduction to World Religions, ed. Christopher Partridge. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2005), 360.

- ↑ Raphael Patai, Jadid al-Islam: The Jewish "New Muslims" of Meshhed (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997, ISBN 0814326528.)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anidjar, Gil (ed.). "Once More, Once More: Derrida, the Jew, the Arab" Introduction to Jacques Derrida, Acts of Religion. New York & London: Routledge, 2001. ISBN 0415924006

- Arnold, T.W., R. Basset, H.A.R. Gibb, R. Hartmann, and W. Heffening. E.J. Brill's Encyclopaedia of Islam. Brill, 1993. ISBN 978-9004097964

- Goody, Jack. The Logic of Writing and the Organization of Society. Cambridge University Press, 1986. ISBN 0521339626

- MacArhur, John. The MacArthur New Testament Commentary: Romans. (2 Vols) Chicago: Moody Press, [1991] 1996.

- Masumian, Farnaz. Life After Death: A Study of the Afterlife in World Religions. Oxford: Oneworld Publications, 1995. ISBN 1851680748

- Partridge, Christopher A. Introduction to World Religions. Augsburg Fortress Publishers. 2005. ISBN 0800637143

- Patai, Raphael. Jadid al-Islam: The Jewish "New Muslims" of Meshhed. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1997. ISBN 0814326528

- Smith, Jonathan Z. "Religion, Religions, Religious," essay in Mark C. Taylor (ed.), A Guide to Critical Terms for Religious Studies. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998. ISBN 978-0226791562

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.