Hagar

Hagar (Arabic هاجر;, Hajar; Hebrew הָגָר; "Stranger") was an Egyptian-born handmaiden of Abraham's wife Sarah in the Bible. She became Abraham's second wife and the mother of Ishmael. Her history is narrated in the Book of Genesis.

According to the account in Genesis, since Sarah could not have children with Abraham, she offered her slave Hagar to Abraham as his concubine. However, the two women soon became enemies, and after the birth of Sarah's own son Isaac, Abraham sent Hagar into exile at Sarah's direction and God's command (Gen. 21:12).

Hagar is the first biblical woman after Eve to whom God spoke directly. She is a figure of particular importance in the Islamic tradition, both as the mother of Ishmael, with whom she settled near Mecca, and as the ancestor of the prophet Muhammad.

The expulsion of Hagar is a key text in interfaith relations between Judaism and Islam, symbolizing for Palestinians their expulsion from the land during Israel's war of independence in 1948. Jews, who believe that Sarah was justified out of fear for the life of her son Isaac, can take from the story that God approves of forceful measures to defend Israel from Palestinian encroachments. As a step towards peace, perhaps both sides can ask how Sarah and Hagar could have related with each other differently to keep peace and harmony within the family of Abraham.

Hagar in the Bible

The story of Hagar is found in Genesis 16 and 21, where Hagar is identified as an Egyptian slave belonging to Sarah. Being barren for many years, Sarah gives Hagar to her husband Abraham as a second wife, saying "perhaps I can build a family through her" (16:2). After Hagar becomes pregnant, however, she openly despises Sarah. When her mistress abuses her in retaliation, Hagar flees to the wilderness.

In the wilderness, Hagar meets an angel of Yahweh. She is the first biblical woman to encounter such a being. The angel commands her to return and submit to Sarah. He also prophesies that she will give birth to a son named Ishmael, who "will live in enmity with all his brothers." Later, however, God declares to Abraham that Sarah herself will bear him a son. God agrees to bless Hagar's son as well, though it is with Sarah's son that He will establish a special covenant (17:20-21).

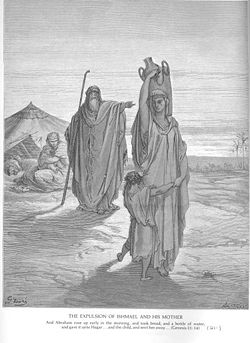

Sarah miraculously conceives and gives birth to Isaac. When the child is weaned, Sarah observes Ishmael, who is 14 years old, "mocking" him in a way that she finds threatening. She demands that Abraham expel Hagar and Ishmael. Abraham protests, but God commands him to grant Sarah's demand: "Listen to whatever Sarah tells you, because it is through Isaac that your offspring will be reckoned. I will make the son of the maidservant into a nation also, because he is your offspring (21:12-13)"

Abraham provides Hagar and Ishmael with bread and water and sends them back into the wilderness.

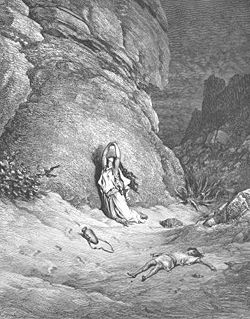

Wandering in the desert near Beersheba, Hagar soon runs out of water and despairs. She leaves Ishmael nearby and sinks into a depression, saying "I cannot watch the boy die." God, however, hears the boy crying and speaks to Hagar: "Lift the boy up and take him by the hand, for I will make him into a great nation."

Suddenly, a spring of fresh water appears. Hagar and Ishmael are rescued. Mother and son settle in the area, and Hagar eventually finds a wife for Ishmael in Egypt. Within two generations, Hagar's progeny have grown to become a trading clan traveling between Egypt and Canaan. It is thus a caravan of Ishmaelites who buy the boy Joseph from his scheming brothers and sell him to one of Pharaoh's officials (Gen. 37:28).

Hagar's male grandchildren are listed the Book of Chronicles (1:29-30): Nebaioth, Kedar, Adbeel, Mibsam, Mishma, Dumah, Massa, Hadad, Tema, Jetur, Naphish, and Kedemah. Hagar's granddaughter Mahalath married Isaac's son Esau and thus become one of the ancestors of the Edomites, according to biblical tradition (Gen. 28:9).

New Testament

In his letter to the Galatians, Paul presents a midrash on the story of Hagar to explain the enmity between Jews and Christians. He equates the Christians with Isaac, the offspring of Sarah, while equating the Jews with the offspring of Hagar. Comparing the persecution of Christians by the Jews to the mistreatment of Isaac by his older brother Ishmael, he suggests that Jews do not share in the inheritance of Christians:

Now you, brothers, like Isaac, are children of promise. At that time the son born in the ordinary way persecuted the son born by the power of the Spirit. It is the same now. But what does the Scripture say? "Get rid of the slave woman and her son, for the slave woman's son will never share in the inheritance with the free woman's son" (Gal. 4:28-29).

Jewish exegesis

Jewish interpretations, as collected in the Midrash Rabbah, focus mainly on what can be surmised or inferred about the plain historical sense of the story; there is no effort to derive any larger theological meaning from it.

The rabbis note several good qualities in Hagar. For example, while Samson's father was struck with fear when he saw the angel of God (Judges 13:22), Hagar was not frightened by the approach of this awesome messenger. Her fidelity is also praised even after Abraham sent her away; she kept her marriage vow to him. One tradition explains that after the death of Sarah, Isaac brought Hagar back to Abraham's house, where she lived with him until his death (Gen. R. 60). Hagar was among the gifts Pharaoh gave to Sarah after when she and her husband had been sojourning in Egypt and were about to return to Canaan. One rabbi speculated that Hagar might be a daughter of Pharaoh himself (Gen. R. 45).

Nevertheless, believing as they do that Sarah was justified in expelling Hagar, the rabbis also find fault with Hagar and point out reasons that justified her expulsion. Hagar reportedly gossiped viciously about Sarah (Gen. R. 45). It is suggested that Hagar's faith was weak, and that she relapsed into idolatry in the wilderness. Also, the fact that she chose an Egyptian woman as her son's wife is seen as evidence that her belief in the true God was not sincere (Gen. R. 53). Finally, there is the notion that her son not only mocked Isaac, but sought to kill him.[1]

Modern critical views

Liberation theology and feminist traditions find identity with Hagar as an example of the silently victimized woman. The conflict between Sarah and Hagar is sometimes used as a classic example of conflicts between women under patriarchal systems.

The expulsion of Hagar is a key text in interfaith relations between Judaism and Islam. Palestinians identify Hagar's expulsion at the hand of Sarah with their plight as a people unjustly subjugated by Israel. Jews, who take the Bible's view that Sarah was justified in expelling her out of fear for the life of her son Isaac (the second time, when God approved it), therefore defend the need for forceful measures to protect Israel from Palestinian encroachments. Taking the story as symbolic of the present-day conflict, in the interests of peace both sides can ask how Sarah and Hagar could have related with each other differently to keep peace and harmony within the family of Abraham.

Hagar in Islam

Hagar is quite important in Islam as the mother of Ishmael and all the Arab peoples, from which descended Muhammad. In the Qur'an, part of the story of Hagar and Ishmael takes place in Mecca. The hadith of Abu Huraira follows a similar line to the rabbinical tradition that Hagar (Hajar) became Sarah's slave as a gift from the king with whom Sarah stayed temporarily as Abraham's "sister."

The tyrant then gave Hajar as a girl-servant to Sarah. Sarah came back (to Ibrahim) while he was praying. Ibrahim, gesturing with his hand, asked, "What has happened?" She replied, "Allah has spoiled the evil plot of the infidel and gave me Hajar for service." Abu Huraira then addressed his listeners saying, "That (Hajar) was your mother, O you Arabs, the descendants of Ishmael, Hajar's son" (Sahih Bukhari 4.577-578; Sahih Bukhari 7.21).

Ibrahim, by God's command, accepted Sarah's request to send Hajar and Ishmael away. Under the guidance of God, they entered the land of Mecca. The baby was overcome with weakness; it seemed that he was passing the last moments of life. Hajar ran seven times back and forth in the scorching heat between the two hills of Safa and Marwa, trying to spot any water in the area, until, completely disappointed and with tear-filled eyes, she returned to her baby. During the hajj, the pilgrimage to Mecca, Muslims remember the agony of Hagar in her search for water by a ritual of walking (sa`i, Arabic: سَعِي) between these two hills.

Allah then sent the Angel Jibril (Gabriel) who struck the ground and from that spot, a clear spring gushed out and began to flow under Ishmael's feet. The spring supposedly still exists today and is called the Zamzam Well.

Little by little, birds came to use the water of the spring. The tribe of Jorhom, who dwelt in the area, discovered the spring because of the birds flying overhead and the tribe then settled beside it. They asked her permission to use the spring and she agreed. From time to time, Ibrahim would go to see Hagar and his child. Visiting them made him happy and reinvigorated him.

In Islamic belief, it was Hajar's son Ishmael, not Isaac, whom Ibrahim offered to God as a sacrifice. Ishmael is seen as a fully legitimate son of Abraham who inherited equally from his father the legacy of prophethood and the religion of Allah. From Ishmael descended the Prophet Muhammad. The prophet is traced to Adnan, believed to be a descendant of Ishmael through his son Kedar.

Hagar in contemporary Israel

The story of Hagar's expulsion to the desert has acquired some political connotations in modern Israel, being taken up as a symbol of the expulsion of Palestinians during the 1948 Israeli War of Independence.

It was also the subject of a famous debate on the floor of the Knesset between two female parliamentarians—Shulamit Aloni, founder of Meretz (Civil Rights Movement) and Geulah Cohen of Tehiya (National Awakening Party)—who argued about which interpretation of Hagar's story should be given in Israeli schools.

The Israeli "Women in Black" movement has unofficially renamed Jerusalem's Paris Square as "Hagar Square." The name commemorates the late Hagar Rublev, a prominent Israeli feminist and peace activist.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fischbein, Jessie. Infertility in the Bible: How The Matriarchs Changed Their Fate; How You Can Too. Devora Publishing, 2005. ISBN 978-1932687347.

- Frymer-Kensky, Tikva. Reading the Women of the Bible: A New Interpretation of Their Stories. Schocken, 2002. ISBN 978-0805241211.

- Murphy, Claire R. Daughters of the Desert: Stories of Remarkable Women from Christian, Jewish, and Muslim Traditions. SkyLight Paths, 2003. ISBN 1893361721.

- Trible, Phyllis (ed.). Hagar, Sarah, And Their Children: Jewish, Christian, And Muslim Perspectives. Westminster John Knox Press, 2006. ISBN 978-0664229825.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.