Maccabees

The Maccabees (Hebrew: מכבים or מקבים, Makabim) were Jewish rebels who fought against the rule of Antiochus IV Epiphanes of the Hellenistic Seleucid dynasty, who was succeeded by his infant son, Antiochus V Eupator. The Maccabees founded the Hasmonean royal dynasty and established Jewish independence in the Land of Israel for about one hundred years, from 165 B.C.E. to 63 B.C.E. Their defeat of a much larger power was a remarkable feat. Israel had not known self-governance since 587 B.C.E. The Hasmoneans succeeded in winning back a considerable portion of Solomon's old empire.

They consolidated their power by centralizing authority in Jerusalem and combining the office of king and High Priest. This attracted criticism from some because the Hasmonean's were not descended from Moses' brother, Aaron the first High Priest and from others, especially the Pharisees because they exercised both religious and political authority. The Pharisees favored separation. The Hasmoneans tried to purify Judaism of what they saw as corrupt elements, destroying the Samaritan Temple on Mount Gerizim. However, they favored assimilation of Greek culture which was opposed by groups such as the Essenes, who withdrew to the Dead Sea region where they established a rival priesthood and community of the pure. The dynasty's downfall was caused by rivalry within the family and by the arrival of the Romans. In 63 B.C.E., Pompey brought Israel, generally known as Palestine, under Roman jurisdiction and in 37 B.C.E. the Romans supported Herod the Great's usurping of power. Not until the creation of the modern State of Israel would the Jews again know independence.

It would in fact be those who opposed the dynasty established by the Maccabees, the Pharisees, who enabled post-Biblical Judaism not only to survive but also to flourish after the Temple's destruction in 70C.E. with their focus on the Torah and on personal piety. The example of the Maccabees inspired Jews in their struggle to achieve and to defend the modern state of Israel, inspiring some to use guerrilla tactics against the British, who made little effort during their post World War I administration of Palestine to establish the Jewish homeland as mandated by the League of Nations. Remembering the example of the Maccabees reminded Jews that they did not have to be victims but could also be victors.

The biblical books of 1 Maccabees, 2 Maccabees, and 4 Maccabees describe the Maccabean revolt.

The revolt

In 167 B.C.E., after Antiochus issued decrees in Judea forbidding Jewish religious practice, a rural Jewish priest from Modiin, Mattathias the Hasmonean, sparked the revolt against the Seleucid empire by refusing to worship the Greek gods and slaying the Hellenistic Jew who stepped forward to worship an idol. He and his five sons fled to the wilderness of Judea. After Mattathias' death about one year later, his son Judah Maccabee led an army of Jewish dissidents to victory over the Seleucids. The term Maccabees as used to describe the Judean's army is taken from its actual use as Judah's surname.

The revolt itself involved many individual battles, in which the Maccabean forces gained infamy among the Syrian army for their use of guerrilla tactics. After the victory, the Maccabees entered Jerusalem in triumph and religiously cleansed the Temple, reestablishing traditional Jewish worship there.

Following the re-dedication of the temple, the Maccabees supporters were divided over the question of whether to continue fighting. When the revolt began under the leadership of Mattathias, it was seen as a war for religious freedom to end the oppression of the Seleucids; however, as Maccabees realized how successful they had been many wanted to continue the revolt as a war of national self-determination. This conflict led to the exacerbation of the divide between the Pharisees and Saducees under later Hasmonean monarchs such as Alexander Jannaeus.[1]

Every year Jews celebrate Hanukkah in commemoration of Judah Maccabee's victory over the Seleucids and subsequent miracles.

Mention in Deuterocanon

The story of the Maccabees can be found in the Hebrew Bible in the deuterocanonical books of 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees. Books of 3 Maccabees and 4 Maccabees are not directly related to the Maccabees.

Origin of name

The Maccabees proper were Judah Maccabee and his four brothers. However, it is also commonly used to refer to the whole of the dynasty that they established, otherwise known as the Hasmoneans. The name Maccabee was a personal epithet of Judah, and the later generations were not his descendants. Although there is no definitive explanation of what the term means, one suggestion is that the name derives from the Aramaic maqqaba, "the hammer," in recognition of his ferocity in battle. It is also possible that the name Maccabee is an acronym for the Torah verse Mi kamokha ba'elim YHWH, "Who is like unto thee among the mighty, O Lord" (Exodus 15:11).

From revolt to independence

Judah and Jonathan

After five years of war and raids, Judah sought an alliance with the Roman Republic to remove the Greeks: "In the year 161 B.C.E. he sent Eupolemus the son of Johanan and Jason the son of Eleazar, 'to make a league of amity and confederacy with the Romans.'"[2]

A Seleucid army under General Nicanor was defeated by Judah (ib. vii. 26-50) at the Battle of Adasa, with Nicanor himself killed in action. Next, Bacchides was sent with Alcimus and an army of twenty thousand infantry and two thousand cavalry, and met Judah at The Battle of Elasa (Laisa), where this time it was the Hasmonean commander who was killed. (161/160 B.C.E.). Bacchides now established the Hellenists as rulers in Israel; and upon Judah's death, the persecuted patriots, under Jonathan, brother of Judah, fled beyond the Jordan River (ib. ix. 25-27). They set camp near a morass by the name of Asphar, and remained, after several engagements with the Seleucids, in the swamp in the country east of the Jordan.

Following the death of his puppet governor Alcimus, High Priest of Jerusalem, Bacchides felt secure enough to leave the country, but two years after the departure of Bacchides from Israel, the City of Acre felt sufficiently threatened by Maccabee incursions to contact Demetrius and request the return of Bacchides to their territory. Jonathan and Simeon, now more experienced in guerilla warfare, thought it well to retreat farther, and accordingly fortified in the desert a place called Beth-hogla; there they were besieged several days by Bacchides. Jonathan contacted the rival general with offers of a peace treaty and exchange of prisoners of war. Bacchides readily consented and even took an oath of nevermore making war upon Jonathan. He and his forces then vacated Israel. The victorious Jonathan now took up his residence in the old city of Michmash. From there he endeavored to clear the land of "the godless and the apostate."[3]

Seleucid civil conflict

An important external event brought the design of the Maccabeans to fruition. Demetrius I Soter's relations with Attalus II Philadelphus of Pergamon (reigned 159 B.C.E. - 138 B.C.E.), Ptolemy VI of Egypt (reigned 163 B.C.E. - 145 B.C.E.) and his co-ruler Cleopatra II of Egypt were deteriorating, and they supported a rival claimant to the Seleucid throne: Alexander Balas, who purported to be the son of Antiochus IV Epiphanes and a first cousin of Demetrius. Demetrius was forced to recall the garrisons of Judea, except those in the City of Acre and at Beth-zur, to bolster his strength. Furthermore, he made a bid for the loyalty of Jonathan, permitting him to recruit an army and to reclaim the hostages kept in the City of Acre. Jonathan gladly accepted these terms, took up residence at Jerusalem in 153 B.C.E., and began fortifying the city.

Alexander Balas contacted Jonathan with even more favorable terms, including official appointment as High Priest in Jerusalem, and despite a second letter from Demetrius promising prerogatives that were almost impossible to guarantee,[4] Jonathan declared allegiance to Alexander. Jonathan became the official leader of his people, and officiated at the Feast of Tabernacles of 153 B.C.E. wearing the High Priest's garments. The Hellenistic party could no longer attack him without severe consequences.

Soon, Demetrius lost both his throne and life, in 150 B.C.E. The victorious Alexander Balas was given the further honor of marriage to Cleopatra Thea, daughter of his allies Ptolemy VI and Cleopatra II. Jonathan was invited to Ptolemais for the ceremony, appearing with presents for both kings, and was permitted to sit between them as their equal; Balas even clothed him with his own royal garment and otherwise accorded him high honor. Balas appointed Jonathan as strategos and "meridarch" (that is, civil governor of a province; details not found in Josephus), and sent him back with honors to Jerusalem[5] and refused to listen to the Hellenistic party's complaints against Jonathan.

Hasmoneans under Balas and Demetrius II

In 147 B.C.E., Demetrius II Nicator, a son of Demetrius I Soter, claimed Balas' throne. The governor of Coele-Syria, Apollonius Taos, used the opportunity to challenge Jonathan to battle, saying that the Jews might for once leave the mountains and venture out into the plain. Jonathan and Simeon led a force of 10,000 men against Apollonius' forces in Jaffa, which was unprepared for the rapid attack and opened the gates in surrender to the Jewish forces. Apollonius received reinforcements from Azotus and appeared in the plain in charge of 3,000 men including superior cavalry forces. Jonathan assaulted, captured and burned Azotus along with the resident temple of Dagon and the surrounding villages.

Alexander Balas honored the victorious High Priest by giving him the city of Ekron along with its outlying territory. The people of Azotus complained to King Ptolemy VI, who had come to make war upon his son-in-law, but Jonathan met Ptolemy at Jaffa in peace and accompanied him as far as the River Eleutherus. Jonathan then returned to Jerusalem, maintaining peace with the King of Egypt despite their support for different contenders for the Seleucid throne.[6]

Hasmoneans under Demetrius and Diodotus

In 145 B.C.E., the Battle of Antioch resulted in the final defeat of Alexander Balas by the forces of his father-in-law Ptolemy VI. Ptolemy himself was however among the casualties of the battle. Demetrius II Nicator remained sole ruler of the Seleucid Empire and became the second husband of Cleopatra Thea.

Jonathan owed no allegiance to the new King and took this opportunity to lay siege to the Akra, the Seleucid fortress in Jerusalem and the symbol of Seleucid control over Judea. It was heavily garrisoned by a Seleucid force and offered asylum to Jewish Hellenists.[7] Demetrius was greatly incensed; he appeared with an army at Ptolemais and ordered Jonathan to come before him. Without raising the siege Jonathan, accompanied by the elders and priests, went to the king, and pacified him with presents, so that the king not only confirmed him in his office of high priest, but gave to him the three Samaritan toparchies of Mount Ephraim, Lod, and Ramathaim-Zophim. In consideration of a present of 300 talents the entire country was exempted from taxes, the exemption being confirmed in writing. Jonathan in return lifted the siege of the Akra and left it in Seleucid hands.

Soon however, a new claimant to the Seleucid throne appeared in the person of the young Antiochus VI Dionysus, son of Alexander Balas and Clepatra Thea. He was three-years-old at most but general Diodotus Tryphon used him to advance his own designs on the throne. In face of this new enemy, Demetrius not only promised to withdraw the garrison from the City of Acre, but also called Jonathan his ally and requested him to send troops. The 3,000 men of Jonathan protected Demetrius in his capital, Antioch, against his own subjects.[8]

As Demetrius II did not keep his promise, Jonathan thought it better to support the new king when Diodotus Tryphon and Antiochus VI seized the capital, especially as the latter confirmed all his rights and appointed his brother Simeon strategos of the seacoast, from the "Ladder of Tyre" to the frontier of Egypt.

Jonathan and Simeon were now entitled to make conquests; Ashkelon submitted voluntarily while Gaza was forcibly taken. Jonathan vanquished even the strategi of Demetrius II far to the north, in the plain of Hazar, while Simeon at the same time took the strong fortress of Beth-zur on the pretext that it harbored supporters of Demetrius.[9]

Like Judah in former years, Jonathan sought alliances with foreign peoples. He renewed the treaty with the Roman Republic, and exchanged friendly messages with Sparta and other places. However one should note that the documents referring to those diplomatic events are questionable in authenticity.

Diodotus Tryphon went with an army to Judea and invited Jonathan to Scythopolis for a friendly conference, and persuaded him to dismiss his army of 40,000 men, promising to give him Ptolemais and other fortresses. Jonathan fell into the trap; he took with him to Ptolemais 1,000 men, all of whom were slain; he himself was taken prisoner.[10]

Simon assumes leadership

When Diodotus Tryphon was about to enter Judea at Hadid, he was confronted by the new Jewish leader, Simeon, ready for battle. Trypho, avoiding an engagement, demanded one hundred talents and Jonathan's two sons as hostages, in return for which he promised to liberate Jonathan. Although Simeon did not trust Diodotus Tryphon, he complied with the request in order that he might not be accused of the death of his brother. But Diodotus Tryphon did not liberate his prisoner; angry that Simeon blocked his way everywhere and that he could accomplish nothing, he executed Jonathan at Baskama, in the country east of the Jordan.[11] Jonathan was buried by Simeon at Modin. Nothing is known of his two captive sons. One of his daughters was the ancestress of Josephus.[12]

Simon assumed the leadership (142 B.C.E.). Simon received the double office of high priest and prince of Israel. The leadership of the Hasmoneans was established by a resolution, adopted in 141 B.C.E., at a large assembly "of the priests and the people and of the elders of the land, to the effect that Simon should be their leader and high priest forever, until there should arise a faithful prophet" (I Macc. xiv. 41). Ironically, the election was performed in Hellenistic fashion.

Simon, having made the Jewish people semi-independent of the Seleucid Greeks, reigned from 142 B.C.E. to 135 B.C.E., and formed the Hasmonean dynasty. Recognition of the new dynasty by the Romans was accorded by the Roman Senate c. 139 B.C.E., when the delegation of Simon was in Rome.

Simon led the people in peace and prosperity, until in February 135 B.C.E., he was assassinated at the instigation of his son-in-law Ptolemy, son of Abubus (also spelt Abobus or Abobi), who had been named governor of the region by the Seleucids. Simon's eldest sons, Mattathias and Judah, were also murdered.

Hasmonean expansion and civil war

John Hyrcanus, Simon's third son, assumed the leadership and ruled from 135 to 104 B.C.E. As Ethnarch and High Priest of Jerusalem, Hyrcanus annexed Trans-Jordan, Samaria, Galilee, Idumea (also known as Edom), and forced Idumeans to convert to Judaism:

Hyrcanus… subdued all the Idumeans; and permitted them to stay in that country, if they would circumcise their genitals, and make use of the laws of the Jews; and they were so desirous of living in the country of their forefathers, that they submitted to the use of circumcision, (25) and of the rest of the Jewish ways of living; at which time therefore this befell them, that they were hereafter no other than Jews.[13]

He desired that his wife succeed him as head of the government, with his eldest of five sons, Aristobulus I, becoming only the high-priest.

Pharisee and Sadducee factions

It is difficult to state at what time the Pharisees, as a party, arose. Josephus first mentions them in connection with Jonathan, the successor of Judas Maccabeus ("Ant." xiii. 5, § 9). One of the factors that distinguished the Pharisees from other groups prior to the destruction of the Temple was their belief that all Jews had to observe the purity laws (which applied to the Temple service) outside the Temple. The major difference, however, was the continued adherence of the Pharisees to the laws and traditions of the Jewish people in the face of assimilation. As Josephus noted, the Pharisees were considered the most expert and accurate expositors of Jewish law.

During the Hasmonean period, the Sadducees and Pharisees functioned primarily as political parties. Although the Pharisees had opposed the wars of expansion of the Hasmoneans and the forced conversions of the Idumeans, the political rift between them became wider when Pharisees demanded that the Hasmonean king Alexander Jannaeus choose between being king and being High Priest. In response, the king openly sided with the Sadducees by adopting their rites in the Temple. His actions caused a riot in the Temple and led to a brief civil war that ended with a bloody repression of the Pharisees, although at his deathbed the king called for a reconciliation between the two parties. Alexander was succeeded by his widow, Salome Alexandra, whose brother was Shimon ben Shetach, a leading Pharisee. Upon her death her elder son, Hyrcanus, sought Pharisee support, and her younger son, Aristobulus, sought the support of the Sadducees. The conflict between Hyrcanus and Aristobulus culminated in a civil war that ended when the Roman general Pompey captured Jerusalem in 63 B.C.E. and inaugurated the Roman period of Jewish history.

Josephus attests that Salome Alexandra was very favorably inclined toward the Pharisees and that their political influence grew tremendously under her reign, especially in the institution known as the Sanhedrin. Later texts like the Mishnah and the Talmud record a host of rulings ascribed to the Pharisees concerning sacrifices and other ritual practices in the Temple, torts, criminal law, and governance. The influence of the Pharisees over the lives of the common people remained strong and their rulings on Jewish law were deemed authoritative by many. Although these texts were written long after these periods, many scholars have said that they are a fairly reliable account of history during the Second Temple era.

Upon Hyrcanus' death, however, Aristobulus, jailed his mother and three brothers, including Alexander Jannaeus, and allowed her to starve there. By this means he came into the possession of the throne, but died one year later after a painful illness in 103 B.C.E.

Aristobulus' brothers were freed from prison by his widow; Alexander reigned from 103 to 76 B.C.E., and died during the siege of the fortress Ragaba.

Alexander was followed by his wife, Salome Alexandra, who reigned from 76 to 67 B.C.E. She serves as the only regnant Jewish Queen. During her reign, her son Hyrcanus II held the office of high priest and was named her successor.

Civil war

Hyrcanus II had scarcely reigned three months when his younger brother, Aristobulus II rose in rebellion; whereupon Hyrcanus advanced against him at the head of an army of mercenaries and his Sadducee followers: "NOW Hyrcanus was heir to the kingdom, and to him did his mother commit it before she died; but Aristobulus was superior to him in power and magnanimity; and when there was a battle between them, to decide the dispute about the kingdom, near Jericho, the greatest part deserted Hyrcanus, and went over to Aristobulus."[14]

Hyrcanus took refuge in the citadel of Jerusalem; but the capture of the Temple by Aristobulus II compelled Hyrcanus to surrender. A peace was then concluded, according to the terms of which Hyrcanus was to renounce the throne and the office of high priest (comp. Schürer, "Gesch." i. 291, note 2), but was to enjoy the revenues of the latter office:

But Hyrcanus, with those of his party who staid with him, fled to Antonia, and got into his power the hostages that might he for his preservation (which were Aristobulus's wife, with her children); but they came to an agreement before things should come to extremities, that Aristobulus should be king, and Hyrcanus should resign that up, but retain all the rest of his dignities, as being the king's brother. Hereupon they were reconciled to each other in the temple, and embraced one another in a very kind manner, while the people stood round about them; they also changed their houses, while Aristobulus went to the royal palace, and Hyrcanus retired to the house of Aristobulus (Aristobulus ruled from 67-63 B.C.E.).

From 63 to 40 B.C.E. the government was in the hands of Hyrcanus II as High Priest and Ethnarch, although effective power was in the hands of his adviser Antipater the Idumaean.

Intrigues of Antipater

The struggle would have ended here but for Antipater the Idumean. Antipater saw clearly that it would be easier to reach the object of his ambition, the control of Judea, under the government of the weak Hyrcanus than under the warlike and energetic Aristobulus. He accordingly began to impress upon Hyrcanus' mind that Aristobulus was planning his death, finally persuading him to take refuge with Aretas, king of the Nabatæans. Aretas, bribed by Antipater, who also promised him the restitution of the Arabian towns taken by the Hasmoneans, readily espoused the cause of Hyrcanus and advanced toward Jerusalem with an army of fifty thousand. During the siege, which lasted several months, the adherents of Hyrcanus were guilty of two acts which greatly incensed the majority of the Jews: they stoned the pious Onias (see Honi ha-Magel), and, instead of a lamb which the besieged had bought of the besiegers for the purpose of the paschal sacrifice, sent a pig. Honi, ordered to curse the besieged, prayed: "Lord of the universe, as the besieged and the besiegers both belong to Thy people, I beseech Thee not to answer the evil prayers of either." The pig incident is derived from rabbinical sources. According to Josephus, the besiegers kept the enormous price of one thousand drachmas they had asked for the lamb.

Roman intervention

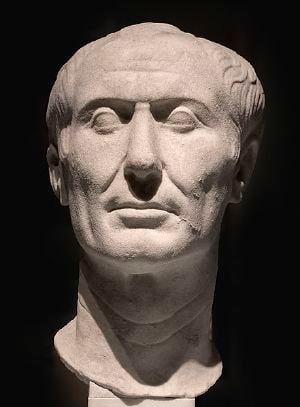

Pompey the Great

While this civil war was going on the Roman general Marcus Aemilius Scaurus went to Syria to take possession, in the name of Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, of the kingdom of the Seleucids. He was appealed to by the brothers, each endeavoring by gifts and promises to win him over to his side. At first Scaurus, moved by a gift of four hundred talents, decided in favor of Aristobulus. Aretas was ordered to withdraw his army from Judea, and while retreating suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Aristobulus. But when Pompey came to Syria (63 B.C.E.) a different situation arose. Pompey, who had just been awarded the title "conqueror of Asia" due to his decisive victories in Asia Minor over Pontus and the the Seleucid Empire, had decided to bring Judea under the rule of the Romans. He took the same view of Hyrcanus' ability, and was actuated by much the same motives as Antipater: as a ward of Rome, Hyrcanus would be more acceptable than Aristobulus. When, therefore, the brothers, and delegates of the people's party, which, weary of Hasmonean quarrels, desired the extinction of the dynasty, presented themselves before Pompey, he delayed the decision, in spite of Aristobulus' gift of a golden vine valued at five hundred talents. The latter, however, fathomed the designs of Pompey, and entrenched himself in the fortress of Alexandrium; but, soon realizing the uselessness of resistance, surrendered at the first summons of the Romans, and undertook to deliver Jerusalem over to them. The patriots, however, were not willing to open their gates to the Romans, and a siege ensued which ended with the capture of the city. Pompey entered the Holy of Holies; this was only the second time that someone had dared to penetrate into this sacred spot. Judaea had to pay tribute to Rome and was placed under the supervision of the Roman governor of Syria.

In 57-55 B.C.E., Aulus Gabinius, proconsul of Syria, split the former Hasmonean Kingdom into Galilee, Samaria & Judea with five districts of legal and religious councils known as sanhedrin (Greek: συνέδριον, "synedrion"): And when he had ordained five councils (συνέδρια), he distributed the nation into the same number of parts. So these councils governed the people; the first was at Jerusalem, the second at Gadara, the third at Amathus, the fourth at Jericho, and the fifth at Sepphoris in Galilee.[15]

Pompey and Caesar

Between the weakness of Hyrcanus and the ambition of Aristobulus, Judea lost its independence. Aristobulus was taken to Rome a prisoner, and Hyrcanus was reappointed high priest, but without political authority. When, in 50 B.C.E., it appeared as though Julius Caesar was interested in using Aristobulus and his family as his clients to take control of Judea against Hyrcanus and Antipater, who were beholden to Pompey, supporters of Pompey had Aristobulus poisoned in Rome, and executed Alexander in Antioch. However, Pompey's pawns soon had occasion to turn to the other side:

At the beginning of the civil war between [Caesar] and Pompey, Hyrcanus, at the instance of Antipater, prepared to support the man to whom he owed his position; but when Pompey was murdered, Antipater led the Jewish forces to the help of Caesar, who was hard pressed at Alexandria. His timely help and his influence over the Egyptian Jews recommended him to Caesar's favor, and secured for him an extension of his authority in Palestine, and for Hyrcanus the confirmation of his ethnarchy. Joppa was restored to the Hasmonean domain, Judea was granted freedom from all tribute and taxes to Rome, and the independence of the internal administration was guaranteed.[16]

The timely aid from Antipater and Hyrcanus led the triumphant Caesar to ignore the claims of Aristobulus's younger son, Antigonus the Hasmonean, and to confirm Hyrcanus and Antipater in their authority, despite their previous allegiance to Pompey. Josephus noted,

Antigonus… came to Caesar… and accused Hyrcanus and Antipater, how they had driven him and his brethren entirely out of their native country… and that as to the assistance they had sent [to Caesar] into Egypt, it was not done out of good-will to him, but out of the fear they were in from former quarrels, and in order to gain pardon for their friendship to [his enemy] Pompey.[14]

Hyrcanus' restoration as ethnarch in 47 B.C.E. coincided with Caesar's appointment of Antipater as the first Roman Procurator, allowing Antipater to promote the interests of his own house: "Caesar appointed Hyrcauus to be high priest, and gave Antipater what principality he himself should choose, leaving the determination to himself; so he made him procurator of Judea."[17]

Antipater appointed his sons to positions of influence: Phasael became Governor of Jerusalem, and Herod Governor of Galilee. This led to increasing tension between Hyrcanus and the family of Antipater, culminating in a trial of Herod for supposed abuses in his governorship, which resulted in Herod's flight into exile in 46 B.C.E. Herod soon returned, however, and the honors to Antipater's family continued. Hyrcanus' incapacity and weakness were so manifest that, when he defended Herod against the Sanhedrin and before Mark Antony, the latter stripped Hyrcanus of his nominal political authority and his title, bestowing them both upon the accused.

Caesar was assassinated in 44 B.C.E. and unrest and confusion spread throughout the Roman world, including to Judaea. Antipater the Idumean was assassinated by a rival, Malichus, in 43 B.C.E., but Antipater's sons managed to kill Malichus and maintain their control over Judea and their father's puppet Hasmonean, Hyrcanus.

Parthian invasion, Antony, Augustus

After Julius Caesar was murdered in 44 B.C.E., Quintus Labienus, a Roman republican general and ambassador to the Parthians, sided with Brutus and Cassius in the Liberators' civil war; after their defeat Labienus joined the Parthians and assisted them in invading Roman territories in 40 B.C.E. The Parthian army crossed the Euphrates and Labienus was able to entice Mark Antony's Roman garrisons around Syria to rally to his cause. The Parthians split their army, and under Pacorus conquered the Levant from the Phoenician coast through Palestine:

Antigonus… roused the Parthians to invade Syria and Palestine, [and] the Jews eagerly rose in support of the scion of the Maccabean house, and drove out the hated Idumeans with their puppet Jewish king. The struggle between the people and the Romans had begun in earnest, and though Antigonus, when placed on the throne by the Parthians, proceeded to spoil and harry the Jews, rejoicing at the restoration of the Hasmonean line, thought a new era of independence had come.[16]

When Phasael and Hyrcanus II set out on an embassy to the Parthians, the Parthians instead captured them. Antigonus, who was present, cut off Hyrcanus's ears to make him unsuitable for the high priesthood, while Phasael was put to death. Antigonus, whose Hebrew name was Mattathias, bore the double title of king and high priest for only three years, as he had not disposed of Herod, the most dangerous of his enemies. Herod fled into exile and sought the support of Mark Antony. Herod was designated "King of the Jews" by the Roman Senate in 40 B.C.E.: Antony

then resolved to get [Herod] made king of the Jews… [and] told [the Senate] that it was for their advantage in the Parthian war that Herod should be king; so they all gave their votes for it. And when the senate was separated, Antony and Caesar [Augustus] went out, with Herod between them; while the consul and the rest of the magistrates went before them, in order to offer sacrifices [to the Roman gods], and to lay the decree in the Capitol. Antony also made a feast for Herod on the first day of his reign.[14]

The struggle thereafter lasted for some years, as the main Roman forces were occupied with defeating the Parthians and had few additional resources to use to support Herod. After the Parthians' defeat, Herod was victorious over his rival in 37 B.C.E. Antigonus was delivered to Antony and executed shortly thereafter. The Romans assented to Herod's proclamation as King of the Jews, bringing about the end of the Hasmonean rule over Judea.

Herod and the end of the dynasty

Antigonus was not, however, the last Hasmonean. The fate of the remaining male members of the family under Herod was not a happy one. Aristobulus III, grandson of Aristobulus II through his elder son Alexander, was briefly made high priest, but was soon executed (36 B.C.E.) due to Herod's jealousy. His sister, Mariamne was married to Herod, but fell victim to his notorious jealousy. Her sons by Herod, Aristobulus IV and Alexander, were in their adulthood also executed by their father.

Hyrcanus II had been held by the Partians since 40 B.C.E. For four years, until 36 B.C.E., he lived amid the Babylonian Jews, who paid him every mark of respect. In that year Herod, who feared that Hyrcanus might induce the Parthians to help him regain the throne, invited him to return to Jerusalem. In vain did the Babylonian Jews warn him. Herod received him with every mark of respect, assigning to him the first place at his table and the presidency of the state council, while awaiting an opportunity to get rid of him. As the last remaining Hasmonean, Hyrcanus was too dangerous a rival for Herod. In the year 30 B.C.E., charged with plotting with the King of Arabia, Hyrcanus was condemned and executed.

The later Herodian rulers Agrippa I and Agrippa II both had Hasmonean blood, as Agrippa I's father was Aristobulus IV, son of Herod by Mariamne I.

The Maccabees and the Hasmoneans

Maccabees

- Mattathias, 170 B.C.E.–167 B.C.E.

- Judas Maccabeus, 167 B.C.E.–160 B.C.E.

- Jonathan Maccabeus, 153 B.C.E.–143 B.C.E. (first to hold the title of High Priest)

- Simon Maccabeus, 142 B.C.E.-141 B.C.E.

Ethnarchs and High Priests of Judaea

- Simon, 141 B.C.E.–135 B.C.E.

- Hyrcanus I, 134 B.C.E.–104 B.C.E.

Kings and High Priests of Judaea

- Aristobulus I, 104 B.C.E.–103 B.C.E.

- Alexander Jannaeus, 103 B.C.E.– 76 B.C.E.

- Salome Alexandra, 76 B.C.E.–67 B.C.E. (Queen of Judaea)

- Hyrcanus II, 67 B.C.E.–66 B.C.E.

- Aristobulus II, 66 B.C.E.–63 B.C.E.

- Hyrcanus II, 63 B.C.E.–40 B.C.E. (restored but demoted to Ethnarch)

- Antigonus, 40 B.C.E.-37 B.C.E.

- Aristobulus III, 36 B.C.E. (only as High Priest)

Legacy and scholarship

While the Hasmonean dynasty managed to create an independent Jewish kingdom, its successes were rather short-lived, and the dynasty by and large failed to live up to the nationalistic momentum the Maccabee brothers had gained. On the other hand, Judaism's survival as a religion would largely build on the tradition of Torah-centered personal piety favored by the Pharisees, for whom the Temple played a less important role. Indeed, although they matured during the Hasmonean or Maccabean period, their roots where in the experience of exile, when the Torah largely substituted for the Temple, and the synagogue as a place of study and later worship developed.

Jewish nationalism

The fall of the Hasmonean Kingdom marked an end to a century of Jewish self-governance, but Jewish nationalism and desire for independence continued under Roman rule, leading to a series of Jewish-Roman wars in the first-second centuries C.E., including the "The Great Revolt" (66–73 C.E.), the Kitos War (115–117), and Bar Kokhba's revolt, (132–135).

A temporary commonwealth was established, but ultimately fell against the sustained might of Rome, and Roman legions under Titus besieged and destroyed Jerusalem, looted and burned Herod's Temple (in the year 70) and Jewish strongholds (notably Gamla in 67 and Masada in 73), and enslaved or massacred a large part of the Jewish population. The defeat of the Jewish revolts against the Roman Empire notably contributed to the numbers and geography of the Jewish Diaspora, as many Jews were scattered after losing their state or were sold into slavery throughout the empire.

Jewish religious scholarship

Jewish tradition holds that the claiming of kingship by the later Hasmoneans led to their eventual downfall, since that title was only to be held by descendants of the line of King David. The Hasmonean bureaucracy was filled with men with Greek names, and the dynasty eventually became very Hellenised, to the annoyance of many of its more traditionally-minded Jewish subjects. Frequent dynastic quarrels also contributed to the view among Jews of later generations of the latter Hasmoneans as degenerate. A member of this school is Josephus, whose accounts are in many cases our sole source of information about the Hasmoneans.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Shaye J. D. Cohen, From the Maccabees to the Mishnah(Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1987, ISBN 9780664219116).

- ↑ I Macc. viii. 7., in Norman Bentwich, Josephus (Bottom of the Hill Publishing, 2013, ISBN 978-1483799155).

- ↑ I Macc. ix. 55-73; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 1, §§ 5-6.

- ↑ I Macc. x. 1-46; Josephus, "Ant." xiii. 2, §§ 1-4

- ↑ I Macc. x. 51-66; Josephus, "Ant." xiii. 4, § 1

- ↑ I Macc. x. 67-89, xi. 1-7; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 4, §§ 3-5.

- ↑ I Macc. xi. 20; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 4, § 9.

- ↑ I Macc. xi. 21-52; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 4, § 9; 5, §§ 2-3.

- ↑ I Macc. xi. 53-74; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 5, §§ 3-7.

- ↑ I Macc. xii. 33-38, 41-53; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 5, § 10; 6, §§ 1-3.

- ↑ 143 B.C.E.; I Macc. xiii. 12-30; Josephus, l.c. xiii. 6, § 5.

- ↑ Josephus, "Vita," § 1.

- ↑ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews, Book XIII, 9:1 Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Flavius Josephus, The Wars of the Jews (East India Publishing Company, 2022, ISBN 978-1774266908).

- ↑ Josephus, Galilee. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Norman Bentwich, Josephus (Bottom of the Hill Publishing, 2013, ISBN 978-1483799155)

- ↑ Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews. Retrieved December 24, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bentwich, Norman. Josephus. Bottom of the Hill Publishing, 2013 (original 1914). ISBN 978-1483799155

- Bickerman, E. J. From Ezra to the Last of the Maccabees; Foundations of Post-Biblical Judaism. New York: Schocken Books, 1962. ISBN 9780805200362

- Cohen, Shaye J. D. From the Maccabees to the Mishnah. Library of early Christianity, 7. Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1987. ISBN 9780664219116

- Josephus, Flavius. The Wars of the Jews. East India Publishing Company, 2022. ISBN 978-1774266908

- Sievers, Joseph. The Hasmoneans and Their Supporters: From Mattathias to the Death of John Hyrcanus I. Atlanta, GA: Scholars Press, 1990. ISBN 9781555404499

External links

All links retrieved March 27, 2025.

- Etymology of "Maccabee"

- Maccabees, The Jewish Encyclopedia

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.