Safed

| Safed | |

| |

| Hebrew | צְפַת |

| (Standard) | Tz'fat |

| Arabic | صفد |

| Founded in | Canaanite age |

| Government | City |

| Also spelled | Tsfat, Tzefat, Zfat, Ẕefat (officially) |

| District | North |

| Coordinates | Coordinates: |

| Population | 30,100[1] (2010) |

| Mayor | Ilan Shohat |

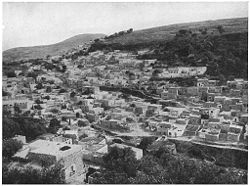

Safed (Hebrew: צְפַת, Tzfat; Arabic: صفد, Safad) is a city in the Northern District of Israel. It is a center for Kabbalah, or Jewish mysticism, and one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Tiberias, and Hebron. At an elevation of 800 meters (2,660 feet) above sea level, Safed is the highest city in the Galilee.

Although Safed played no role in either Jewish of Christian biblical tradition, it became a major center of Jewish intellectual and mystical activity beginning in the late fifteenth century as Spanish and other European Jews came to the city to escape persecution by Christians. The Jewish mystical tradition of the Kabbalah went through a major development here under Rabbi Isaac Luria and his colleagues, and it was also in Safed that Rabbi Joseph Karo wrote the Shulchan Aruch, which became the standard compendium of Jewish law in rabbinical Judaism. The first printing press in the Middle East was also founded at Safed. Nearby Mount Meron is the traditional site of the graves of the great rabbinical sages Hillel, Shammai, and Shimon bar Yochai.

The home to about 30,000 predominately Jewish residents today, Safed is sometimes called the "Mystical City." It attracts many spiritual pilgrims, as well as tourists drawn to its well-known artists' colony and night life.

History

According to the Book of Judges, the region in which Safed is located was assigned to the tribe of Asher. Legend has it that Safed was founded by a son of Noah after the Great Flood. However, the city as such plays no role in the Hebrew Bible or the New Testament. It is mentioned in the Jerusalem Talmud as one of five elevated spots where fires were lit to announce the new moon and other festivals during the Second Temple period. However, other Jewish sources speak of its foundation dating from the second century of the common era (Yer. R. H. 58a). It has also been tentatively identified with Sepph, a fortified Jewish town in the Upper Galilee mentioned in the writings of the Roman Jewish historian Josephus dating to the late first century C.E. (Wars 2:573).

After its mention in the Talmud, Safed disappears from the historical record for many centuries. In the twelfth century, it was a fortified Crusader city known as Saphet. In 1265, the Mamluk sultan Baybars wiped out the Christian population of Safed and turned it into the Muslim city called Safad or Safat. Under the Ottomans, Safed was part of the vilayet (administrative district) of Sidon.

The number of Jews living there at this time is uncertain, but in 1289, Safed had a substantial enough Jewish community that Moses ben Judah ha-Kohen was known as the chief rabbi of the city. In that year he went to nearby Tiberias, the site of the tomb of the Jewish philosopher Maimonides, and pronounced a curse of anathema on all who condemn the great sage's writings. The Jewish community of Safed was apparently not prosperous, for in 1491 the chief rabbi of Safed, Perez Colobo, was so poorly paid that he was obliged to carry on a grocery business.

Safed's golden age

This was soon to change, however, as Safed benefited from the misfortunes of Spanish Jews who were expelled in the following year. In 1492, the community was reorganized by Rabbi Joseph Saragossi, a Spanish immigrant. From this point on, the record becomes more clear. The next chief rabbi of Safed was Jacob Berab (1541), followed by the great Joseph Karo (1575). A Hebrew printing press was established in Safed in 1577 by Eliezer Ashkenazi and his son, Isaac of Prague. It was the first press not only in Palestine, but the whole of the Ottoman Empire.

As a result of the influx of Jews fleeing persecution in Europe during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Safed become a major center of Jewish intellectual activity and mystical thought. It was there that Isaac Luria (1534–1572), Moses ben Jacob Cordovero (1522-1570), and Hayyim ben Joseph Vital (1543-1620) revived Jewish interest in the Kabbalah in Palestine. It was also in Safed that Joseph Karo wrote the great compendium of Jewish law known as the Shulchan Aruch. These two events would have a major impact on the attitudes and practice of Judaism for centuries to come. Moses Galante the Elder held office beginning in 1580, followed by Moses mi-Trani (1590), Joshua ben Nun (1592), Naphtali Ashkenazi (1600), Baruch Barzillai (1650), and Meïr Barzillai (1680).

Declines and revivals

The eighteenth century, however, was a period of decline, as Safed was devastated by the plague in 1742 and an earthquake in 1769. The latter compelled most of the population of Safed to emigrate to Damascus and elsewhere, so that only seven families reportedly remained, compared to nearly 10,000 Jews in 1555.

In 1776, Safed was repopulated by an influx of Russian Jews. Five years later, two Russian rabbis, Löb Santower and Uriah of Vilna, brought a number of families from the Ukraine and elsewhere in Eastern Europe to Safed. The consuls of Russia and Austria took these foreign Jews under their protection during this period of Ottoman rule.

The history of Safed during the first half of the nineteenth century was another series of misfortunes. The plague of 1812 killed four-fifths of the Jewish population. Seven years later, Ottoman commander Abdullah Pasha imprisoned the remainder in his stronghold, and released them only on the payment of ransom. In 1833, at the approach of Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt, the Jewish quarter was plundered by the Druze, although the inhabitants escaped to the suburbs. The following year it was again pillaged, the persecution lasting 33 days. On January 1, 1837, more than 4,000 Jews were again killed by an earthquake, the greater number of them being buried alive in their dwellings. Ten years later the plague again raged at Safed.

Despite these tragedies, the city's attractive site and spiritual reputation continued to attract new residents. In the second half of the nineteenth century Jews emigrated from Persia, Morocco, and Algeria to the city. Its houses and synagogues were rebuilt by the British Jewish philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore, who visited the Safed seven times between 1837 and 1875, and by Isaac Vita of Triest.

Twentieth century strife

As the Zionist movement began to gain momentum in the early twentieth century, episodes of violence between Jews and Arabs occasionally flared in the town. About 20 Jewish residents were murdered in the 1929 Safed massacre. Jewish immigration to Palestine, meanwhile, now focused on other locations more in keeping with the secular Zionist vision. By 1948, Safed was home to 12,000 Arabs, with the city's 1,700 Jews being mostly religious and elderly.

In the Israeli War of Independence, the Arabs fled the city en masse, among them the family of Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas. The city was conquered by Israeli forces on May 11, 1948.

In 1974, 102 Israeli Jewish teenagers from Safed on a school trip to nearby Maalot were taken hostage by a Palestinian terrorist group Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine (DFLP) while sleeping in a school in Maalot, and 21 of them were killed.

In July 2006, Katyusha rockets fired by Hezbollah from Southern Lebanon hit Safed, killing one man and injuring others. On July 14, rockets killed a five year old boy and his grandmother. Many residents fled the town. On July 22, four people were injured in a rocket attack.

Safed today

Demographics

In 2008, the population of Safed was 32,000. Almost entirely Jewish, it is no longer a city of old people, and is noted for its spiritual centers and creative communities, as well as popular night life. According to the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), the ethnic makeup of the city in 2001 was 99.2 percent Jewish, with no significant Arab population. About 43 percent of the residents were 19 years of age or younger, another 13.5 percent between 20 and 29, 17.1 percent between 30 and 44, 12.5 percent from 45 to 59, 3.1 percent from 60 to 64, and 10.5 percent 65 years of age or older.

In December 2001, residents of Safed earned an average of 4,476 shekels per month, compared to the national average of 6,835 shekels. In 2000, there were 6,450 salaried workers and 523 self-employed. A total of 425 residents received unemployment benefits and 3,085 received income supplements.

According to CBS, the city has 25 schools and more than 6,000 students. There are 18 elementary schools with a student population of 3,965, and 11 high schools with a student population of 2,327.

Culture

In the 1950s and 1960s, Safed was known as Israel's art capital. The artists' colony established in Safed's Old City has been a hub of creativity that drew leading artists from around the country, among them Yosl Bergner, Moshe Castel, and Menachem Shemi. Some of Israel's leading art galleries are located there.

In honor of the opening of the Glitzenstein Art Museum in 1953, the artist Mane Katz donated eight of his paintings to the city. During this period, Safed was home to the country's top nightclubs as well.

Known as the "City of the Kabbalah," Safed is also attractive to Jews and other pilgrims with a spiritual bent. Many of the cobblestone streets of the Old City lead to ancient synagogues. The Karo Synagogue, named after the great talmudic scholar of Safed's golden age, boasts of an ark containing a Torah scroll more than 400 years old, while the Ari Synagogue is believed to be housed in the very building where Rabbi Isaac Luria lived for 20 years.

Outside Safed lies the village of Meron, mentioned in the annals of the Egyptian pharaohs whose forces invaded the area c. 1000 B.C.E. It is also the location of synagogue dating to around 300 C.E. According to kabbalistic legend, it was in a nearby cave that Rabbi Shimon bar Yochai wrote the Zohar. In preparation for the festival of Shavuot, thousands of Israelis climb the 4,000 ft. Mount Meron to the tomb of Shimon bar Yochai. Meron is also the traditional site of the graves of the great early rabbinical sages, Hillel and Shammai.

Notes

- ↑ Table 3 - Population of Localities Numbering Above 1,000 Residents and Other Rural Population (PDF). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics (2008-06-30). Retrieved May 25, 2012.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fine, Lawrence. Safed Spirituality: Rules of Mystical Piety, the Beginning of Wisdom. The Classics of western spirituality. New York: Paulist Press, 1984. ISBN 9780809103492.

- Rossoff, Dovid. Safed: The Mystical City. Jerusalem: Shaʼar Books, 1991. ISBN 9780873065665.

- Silverman, Dov. Legends of Safed. Jerusalem: Gefen, 1994. OCLC 38977492.

- Shalem, Yisrael. Safed: Six Self-Guided Tours in and Around the Mystical City. Safed: Safed Regional College, 1991. OCLC 33327603.

- Wisnefsky, Moshe Yaakov, and Chaya Bracha Leiter. Zefat: A Guide for an Inner-Dimensional Journey. Zefat: Ascent Institute, 1986. OCLC 41238417.

- Yizreʻel, Rami, and Janet Weizman. Safad. Jerusalem: Hamakor Press, 1987. OCLC 233681633.

External links

All links retrieved December 22, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.