Difference between revisions of "Freedom of religion" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Antiquity) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (47 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Ebapproved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}} |

| − | + | {{Freedom}} | |

| − | '''Freedom of religion ''' is a political principle guaranteeing ''freedom of belief'' and ''freedom of worship'' for individuals and groups. It is generally recognized to include related freedoms applied to the religious sphere, such as | + | |

| + | '''Freedom of religion''' is a political principle guaranteeing ''freedom of belief'' and ''freedom of worship'' for individuals and groups. It is generally recognized to include related freedoms applied to the [[religion|religious]] sphere, such as the freedoms of speech (evangelism), [[freedom of the press|press]] (production and distribution of literature), travel for [[pilgrimage]]s and meetings, and public assembly for religious purposes. Also included is the right ''not'' to follow any religion and to deny or doubt the existence of any [[deity]]. | ||

The [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]] adopted by the [[United Nations General Assembly]] on December 10, 1948, defines freedom of religion and belief as follows: | The [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]] adopted by the [[United Nations General Assembly]] on December 10, 1948, defines freedom of religion and belief as follows: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes the freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. (Article 18)</blockquote> | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | While this statement of the principles of religious freedom has yet to be established universally, it has gained wide acceptance throughout much of the world, an indication of the advance of humankind toward the realization of a world of peace. | ||

| + | [[Image:Declaration_of_Human_Rights.jpg|thumb|right|The ''[[Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen]]'' guarantees freedom of religious opinion, provided that it "manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law."]] | ||

| + | ==Issues== | ||

| + | {{readout||left|250px|In 1948 the United Nations defined freedom of religion as a universal human right}} | ||

| + | Debates about religious freedom often center on the tension between an individual or group's right to [[worship]] (or to refrain from worship) as they please, versus the [[nation-state|state]]'s interest in maintaining order by imposing or favoring a particular religious culture supportive of the state. In ancient societies, the [[monarchy|king]] was often also the high [[priest]] or even seen as the [[incarnation]] of a [[deity]]. Thus, religious [[pluralism]] that denied the king's religious authority constituted a direct challenge to royal power. | ||

| − | + | Related to religious freedom is the issue of religious tolerance. While tolerance represents a step forward from [[persecution]], mere toleration of religious minorities by [[government]]s does not guarantee their religious freedom, since such groups may face significant disadvantages both legally and in terms of their treatment by [[society]]. On the other hand, absolute freedom of religious practice is problematic, since this would exempt certain religious groups from laws designed to protect citizens from such practices as [[human sacrifice]] or the destruction of "[[idolatry|idolatrous]]" shrines by rival religions. | |

| − | + | A corollary to the principle of freedom of ''worship'' is the freedom to ''practice'' religious duties such as [[pilgrimage]]s, public preaching, and making converts. These duties can sometimes conflict with a state's interests. For example, pilgrimages involve freedom of travel to foreign countries, as well as the entry of foreign citizens into the country in which a particular holy site is located. Public preaching can disrupt "public order" in religiously intolerant societies where the expression of unpopular views can result in riots. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Making converts is directly threatening to the religion from which the converts are made. Where state religions are involved, the state itself may also feel directly threatened when people convert from the state religion to another faith.<ref>State religions vary on this issue. For example, in some [[Islam]]ic states converting from Islam is a capital offense, as is proselytizing among Muslims. On the other hand, the official [[Church of England]], for example, allows other [[faith]]s to preach freely and there is no legal penalty for converting from the state religion. Other European societies provide a preferred status for state-approved religions, putting smaller or less approved groups at a disadvantage.</ref> The principle of [[Separation of Church and State in the United States|separation of church and state]] was designed to prevent states from favoring one religion or a group of religions over minority religions and non-believers. | |

| − | The | + | [[Image:CrossMenorahOxford 20051225KaihsuTai.jpg|thumb|left|The [[Christianity|Christian]] [[crucifix|cross]] of a war memorial and a [[menorah]] for [[Hanukkah]] coexist in Oxford, [[England]]. However, such religious displays on public property are considered offensive by [[atheism|atheists]]]] |

| + | Other religious duties also sometimes run afoul of state interests. An extreme example is the practice of [[human sacrifice]], which was common in some ancient societies. Even in cases where this might be carried out voluntarily, few would argue today that banning this practice constitutes an unnecessary abridgment of religious freedom. Female [[circumcision]], also called [[female genital mutilation]] (FGN), is a more contentious issue, with some [[Islam|Muslim]] groups claiming this to be a religious duty and women's rights groups contending that it constitutes a [[crime]] which must be stopped by the state regardless of the opinions of those participating in the practice. | ||

| − | The | + | The rights of groups such as [[Jehovah's Witnesses]] and [[Christian Science]] practitioners to withhold medical attention from their children is another contentious issue involving the tension between religious freedom and the state's need to protect the [[health]] of its citizens. Some states have sought to ban groups that the state considers "dangerous," ranging from the above-named groups to more recent "sects" accused of [[brainwashing]] new members. Arguing against such policies is the principle in Article 18 of the [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]] affirming the right to change one's religion, implying that this is so even if one's new religion may be unpopular or disturbing to the majority of society.<ref>The UN Human Rights Commission has specifically affirmed that smaller and newer religions, and not just well established ones, are covered by Article 18. Indeed it is these groups that often face the greatest threat of persecution by an intolerant majority.</ref> |

| − | + | Other examples of religious duties impacting on the state are the right of workers to observe [[sabbath]]s and religious holidays without punishment by the employers, the right of minor children to choose a different religion from their parents, the right of prisoners to special religious diets, the right of religious parents to educate their children outside of state schools, the right of [[atheism|atheists]] not to invoke God in legal oaths and pledges of allegiance, and the question of religious monuments on publicly owned property. | |

| − | + | While the basic right of freedom of worship is now generally recognized, such issues as those listed above often involve deeply-held beliefs and result in serious disagreements between governments and religious groups. Moreover, in a number of countries, even the more basic rights of religious freedom still are not upheld. In addition, governments of many nations are either unwilling or unable to prevent religiously intolerant groups from harming members of rival religions. | |

| − | + | ==Ancient History== | |

| − | + | One of the earliest examples of a movement seeking religious freedom for its members is also one of the best-known stories in the Judeo-Christian tradition. Confronting the king of [[Ancient Egypt|Egypt]], the [[Israelite]] leaders [[Moses]] and [[Aaron]] demanded: | |

| − | + | :This is what [[Yahweh|the Lord]], the God of [[Israel]], says: “Let my people go, so that they may hold a festival to me in the desert.” Pharaoh said, “Who is the Lord, that I should obey him and let Israel go?" ([[Exodus, Book of|Exod.]] 5:1-3) | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The story of the [[Exodus]] is cast against a background of religious and ethnic repression. The liberation of the Hebrews, together with the model of Moses confronting the Egyptian king to speak “truth to power,” has served as inspiration for both religious and political movements. It remains an archetype of the principle that one’s conscience takes precedence over any earthly authority. However, once the Israelites gained their own nation in the land of [[Canaan]] they did not grant religious freedom to native peoples but are reported in the Bible to have driven them out and later enacted legislation that repressed all religion except that approved by the [[Jerusalem]] priesthood. | |

| − | + | [[Image:Cyrus II le Grand et les Hébreux.jpg|thumb|300px|[[Cyrus the Great]] meets with [[Jew]]ish leaders returning to rebuild the [[Temple of Jerusalem]]]] | |

| + | The first government declaration promoting a form of religious freedom, indeed the first known human rights document of any kind, was issued in the ancient [[Persian Empire]] by its founder [[Cyrus the Great]]. Cyrus reversed the policy of his [[Babylonian Empire|Babylonian]] predecessors who had destroyed local temples and removed their religious treasures. He returned these religious artifacts to their proper places and funded the restoration of important native shrines, including the [[Temple of Jerusalem]]. The so-called “Cyrus cylinder” dating from 538 B.C.E.., is a remarkable archaeological find. It reads: | ||

| − | [[ | + | <blockquote>I Cyrus, king of the world... when I entered Babylon... [[Marduk]] the great god I sought daily to worship... As far as the region of the land of Gutium, the holy cities beyond the Tigris whose sanctuaries had been in ruins over a long period, the gods whose abode is in the midst of them, I returned to their places and housed them in lasting abodes. [These] gods... at the bidding of Marduk, the great Lord, I made to dwell in peace in their habitations, delightful abodes.</blockquote> |

| − | + | Freedom of religious worship was established as a basic principle during the [[Maurya Empire]] of ancient [[India]] by [[Ashoka]] the Great in the third century B.C.E.., as encapsulated in the Edicts of Ashoka: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>King Piyadasi (Ashoka), dear to the Gods, honors all sects, the ascetics (hermits) or those who dwell at home, he honors them with charity and in other ways... One must not exalt one’s creed discrediting all others, nor must one degrade these others without legitimate reasons. One must, on the contrary, render to other creeds the honor befitting them.</blockquote> | |

| − | The | + | The right to worship freely was promoted by most ancient [[India]]n dynasties until around 1200 C.E. The initial entry of [[Islam]] into [[South Asia]] came in the first century after the death of the Prophet [[Muhammad]]. When around 1210 C.E. the Islamic Sultanates invaded India from the northeast, the principle of freedom of religion gradually deteriorated in this part of the world. |

| − | In | + | In the West, [[Alexander the Great]] and subsequent Greek and [[Roman Empire|Roman]] rulers generally followed a policy of religious toleration, allowing local religions to flourish as long as they also paid homage to the state religion as well. Several notable exceptions arose in relation to the [[Jew]]s, as a result of their insistence that they must acknowledge their own God alone. The religious practice of [[circumcision]] was also an issue between the Greeks and the Jews, as it was considered abhorrent to the Greeks and later the Romans, who occasionally sought to suppress this Jewish practice. The early Christians, at first considered a Jewish sect, faced similar persecutions for refusing to honor the state deities. |

| − | |||

| − | The | ||

| − | + | ==In Early Christianity== | |

| + | The issue of the relation between religion and the state took clearer form in the West as [[Christianity]] came to the fore. [[Jesus of Nazareth|Jesus]] himself became a victim of religious intolerance when, according to the [[New Testament]], he was arrested for his religious teachings and turned over to Rome as a would-be [[Messiah]] by the high priest of [[Judaism]] and his supporters. Christians were first persecuted as a distinct group from the Jews when the Emperor [[Nero]] blamed them for the great fire of [[Rome]] in 68 C.E.. In the early second century, the Emperor [[Trajan]] officially proscribed the Christian religion, and Christians suffered varying degrees of persecution. Over the next two hundred years Christians experienced repression when certain emperors insisted on their adherence to Roman state religious traditions, which many Christians suffered [[martyr]]dom to avoid. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Byzantinischer Mosaizist um 1000 002.jpg|thumb|225px|''[[Constantine I|Constantine the Great]]'', mosaic in the [[Hagia Sophia]], c. 1000 C.E..]] | |

| + | A brighter future emerged for Christianity in the early fourth century as [[Constantine I]] issued the [[Edict of Milan]], which declared to his governors that Christianity would thereafter be legal. The decree ordered the return of any church properties seized under previous administrations. It also guaranteed religious freedom for other religions: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>It has pleased us to remove all conditions whatsoever... concerning the Christians and now any one of these who wishes to observe Christian religion may do so freely and openly, without molestation... We have also conceded to other religions the right of open and free observance of their worship for the sake of the peace of our times.</blockquote> | |

| + | |||

| + | A decade later, however, Constantine embarked on a course less tolerant toward non-Christian religions, intervening on behalf of the “orthodox” party in the [[Arian controversy]] and commanding Christians not to associate with Jews. The state would now be the final arbiter in distinguishing proper doctrine from [[heresy]], and factions within Christianity would vie for imperial support. The state changed sides several times in the Arian controversy before [[Theodosius I]] took power and declared orthodox (Catholic) Christianity to be the official state religion in 392 C.E. Christians then began using the power of the state to persecute other Christians, as well as to pressure pagans to convert to Christianity. | ||

| − | + | [[Ambrose of Milan]] set an important precedent—both for the separation of church and state and for Christian intolerance toward Judaism—when, during the reign of [[Theodosius I]], he succeeded in causing the emperor to back down from forcing a bishop to rebuild a synagogue that had been destroyed by a Christian mob. Ambrose declared that the Christian church cannot be forced by the state to support the religion of non-Christians. Later, Ambrose’s student, [[Augustine of Hippo]], argued successfully that the state should intervene militarily on behalf of the [[Roman Catholic Church]] against the [[Donatism|Donatist]] schism in North Africa. Writing to his spiritual son [[Boniface]], a Roman military leader in that part of the world, Augustine called for a "righteous persecution, which the Church of Christ inflicts upon the impious." However, even as he laid the foundation to justify the church’s cooperation with the state in the persecution of heretics, Augustine simultaneously struck a blow for the primacy of conscience over worldly authority: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Whosoever, therefore, refuses to obey the laws of the emperors which are enacted against the truth of God, wins for himself a great reward; but whosoever refuses to obey the laws of the emperors which are enacted in behalf of truth, wins for himself great condemnation. (A Treatise Concerning the Correction of the Donatists)</blockquote> | |

| − | + | By this time, [[Christianity]] had replaced the [[Roman mythology|Roman gods]] as a state religion. Over the next few centuries, the [[papacy]] would emerge as a bastion of orthodox resistance to state theological error. Emperors sometimes sided with heretics, and "[[barbarian]]s" (who were often Arian Christians) had even sacked [[Rome]]. Facing a crisis in which the Emperor had appointed a heretical bishop to the patriarchal seat in [[Constantinople]], [[Pope Gelasius I]] issued his famous “Two Swords” letter in 494 insisting that in spiritual matters, the church, not the state, was supreme: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>There are two powers, august Emperor, by which this world is chiefly ruled, namely, the sacred authority of the priests and the royal power. Of these that of the priests is the more weighty, since they have to render an account for even the kings of men in the divine judgment. You are also aware, dear son, that while you are permitted honorably to rule over humankind, yet in things divine you bow your head humbly before the leaders of the clergy and await from their hands the means of your salvation.</blockquote> | |

| − | + | ==The rise of Islam== | |

| − | [[ | + | Over the next thousand years church and state in the West strove for power and supremacy in both spiritual and temporal affairs. Meanwhile, a successful new religion had emerged on the scene: [[Islam]]. It quickly grew and became the dominant force in much of the former Eastern [[Roman Empire]]. Islam made no distinction between religion and the temporal state. Despite this, until the modern era, Islam was ahead of its time on the question of religious freedom. People “of the book”—namely Jews and Christians—were allowed to practice their religion in Muslim lands. The [[Qur'an]] declared: |

| − | + | <blockquote>Let there be no compulsion in religion. Truth stands out clear from Error; whoever rejects Evil and believes in Allah hath grasped the most trustworthy hand-hold, that never breaks. And Allah heareth and knoweth all things. (Qur’an 2:256)<ref>[http://www.guidedways.com/chapter_display.php?chapter=2&translator=2 Qur'an in English] Translation by Yusuf Ali. Retrieved May 23, 2017.</ref> </blockquote> | |

| − | + | Yet, other passages in the Qur’an indicated that pagans could be enslaved or even killed if they did not accept Islam. In practice, however, religions such as [[Hinduism]] and [[Buddhism]] usually found a degree of tolerance from Islamic governments. To be sure, Christians in large numbers nevertheless suffered as Islamic armies marched on what had formerly been the Christian Empire in the East, and many were persuaded to convert to Islam by the sword. Nor can it be denied that thousands of Muslims and even many Eastern Christians were slaughtered by European Christians during [[The Crusades]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Medieval Europe== | |

| − | + | ||

| + | [[Jew]]s fared better under Islamic governments than under European Christian ones. A succession of Christian kings expelled Jews from their lands. Jews were forbidden to own property and engage in certain professions. Preachers often blamed them for the [[Crucifixion]] and strongly discouraged Christians from associating with them. The first Crusade, though not directed against the Jews, nonetheless resulted in the massacre of many Jews by crusading Christians, thirsty for infidel blood. At other times, some Christian preachers overtly aroused anti-Jewish mobs to violence. | ||

| − | + | The [[Inquisition]], originally established by [[papal bull]] in 1184, had targeted Christian heretics such as the [[Cathars]] before it turned its sights on Jews. [[Punishment]], which was carried out by the secular government rather than the church courts, ranged from confiscation of property to [[prison]], [[banishment]], and, of course, public [[execution]]. [[Torture]] was not considered punishment, but a permissible tool of church investigators. Targets of the Inquisition included the Cathars of southern France, the [[Waldensians]], the [[Hussites]], the [[Knights Templar]], [[Spiritual Franciscans]], [[witch]]es (the most famous being [[Joan of Arc]]), Jews, Muslims, [[freethinker]]s, and [[Protestant]]s. | |

| − | + | ===The Reformation=== | |

| + | [[Image:Martin Luther by Lucas Cranach der Ältere.jpeg|thumb|left|[[Martin Luther]] portrait by [[Lucas Cranach der Altere|Lucas Cranach der Ältere]]]] | ||

| + | From the standpoint of freedom of belief, perhaps the most memorable moment in the epochal movement of the [[Reformation]] took place at the [[Diet of Worms]] in April 1521, when [[Martin Luther]] risked his life rather than taking the opportunity to recant his views: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>Unless I am convinced by proofs from Scriptures or by plain and clear reasons and arguments, I can and will not retract, for it is neither safe nor wise to do anything against conscience. Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me.</blockquote> | |

| − | + | Though the advent of the Reformation did not immediately mark a new era for religious freedom, it did enable formerly heretical practices, such as translating the [[Bible]] into the vernacular, to flourish. In 1535, the Swiss canton of [[Geneva]] became [[Protestantism|Protestant]], but the Protestants often proved as intolerant of differences of opinion as the Catholics. | |

| − | + | As Europe witnessed a series of wars in which religion played a key role, a seesaw struggle between Protestantism and Catholicism was also evident in England when [[Mary I of England]] returned that country briefly to the Catholic fold in 1553. However, her half-sister, [[Elizabeth I of England]] was to restore the [[Church of England]] in 1558. | |

| − | + | In the [[Holy Roman Empire]], [[Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor|Charles V]] agreed to tolerate Lutheranism in 1555 at the [[Peace of Augsburg]]. Each state was to take the religion of its prince, but within those states, there was not necessarily religious tolerance. Citizens of other faiths could relocate to a more hospitable environment. In 1558, the [[Transylvania]]n [[Diet (assembly)|Diet]] of [[Turda]] declared free practice of both the [[Roman Catholic Church|Catholic]] and [[Lutheranism|Lutheran]] religions, but prohibited [[Calvinism]]. Ten years later, in 1568 the Diet extended the freedom to all religions, declaring that "It is not allowed to anybody to intimidate anybody with captivity or expulsion for his teaching." The [[Edict of Turda]] is considered by mostly [[Hungary|Hungarian]] historians as the first legal guarantee of religious freedom in the Christian Europe. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In France, although peace was made between Protestants and Catholics at the [[Treaty of Saint Germain]] in 1570, persecution continued, most notably in the [[Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre]] on August 24, 1572, in which many Protestants throughout France were killed. It was not until the converted Protestant prince [[Henry IV of France]] came to the throne that religious tolerance was formalized in the [[Edict of Nantes]] in 1598. It would remain in force for over 80 years until its revocation in 1685 by [[Louis XIV of France]]. Intolerance remained the norm until the [[French Revolution]], when state religion was abolished and all church property confiscated. | |

| − | + | In 1573, the [[Warsaw Confederation (1573)|Warsaw Confederation]] formalized in the newly formed [[Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth]] the freedom of religion that had a long tradition in the [[Kingdom of Poland (1385–1569)|Kingdom of Poland]]. | |

| − | + | However, intolerance of dissident forms of Protestantism continued, as evidenced by the exodus of the [[Pilgrims]] who sought refuge, first in [[Netherlands|Holland]], and ultimately in America, founding the [[Plymouth Colony]] in [[Massachusetts]] in 1620. [[William Penn]], the founder of [[Philadelphia]] was involved in a case which had a profound effect upon future American law and that of England. A jury refused to convict William Penn of preaching a [[Quaker]] sermon, which was illegal. Even though the jury was imprisoned for their acquittal, they stood by their decision and helped establish freedom of religion. The [[Puritan]]s in [[England]], on the other hand, would soon demonstrate a more intolerant brand of [[Protestantism]] during the reign of [[Oliver Cromwell]] in the mid-seventeenth century. | |

| − | [[ | + | ===Westphalia: A turning point=== |

| + | The [[Peace of Westphalia]], signed in 1648, afforded international protections to religious groupings on the continent. It marked a turning point in the history of religious freedom in the West and affirmed that: | ||

| + | [[Image:John Locke.jpg|thumb|[[John Locke]]]] | ||

| + | <blockquote>There shall be a Christian and Universal Peace, and a perpetual, true, and sincere Amity, between his Sacred Imperial Majesty [the Holy Roman Emperor], and his most Christian Majesty [of France]; as also, between all and each of the Allies... That this Peace and Amity be observ’d and cultivated with such a Sincerity and Zeal, that each Party shall endeavour to procure the Benefit, Honour and Advantage of the other; that thus on all sides they may see this Peace and Friendship in the Roman Empire, and the Kingdom of France flourish, by entertaining a good and faithful Neighbourhood.</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | The bloody warfare between Catholics and Protestants in England, meanwhile, brought to the fore thinkers such as [[John Locke]], whose [[Essays of Civil Government]] and [[Letter Concerning Toleration]] played a significant role in the [[Glorious Revolution]] of 1688 and later in the [[American Revolution]]. Locke wrote: | |

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>The care of souls cannot belong to the civil magistrate, because his power consists only in outward force; but true and saving religion consists in the inward persuasion of the mind, without which nothing can be acceptable to God. And such is the nature of the understanding, that it cannot be compelled to the belief of anything by outward force. Confiscation of estate, imprisonment, torments, nothing of that nature can have any such efficacy as to make men change the inward judgment that they have framed of things.</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Constitutional guarantees== | |

| + | [[Image:T Jefferson by Charles Willson Peale 1791 2.jpg|thumb|[[Thomas Jefferson]]'s Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom is considered a pioneering model for modern religious freedom legislation]] | ||

| + | Locke’s ideas on the primacy of conscience over both church and state were to be further enshrined in the American [[Declaration of Independence (United States)|Declaration of Independence]], written by [[Thomas Jefferson]] in 1776. Another of Jefferson's works, the 1779 [[Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom]], proclaimed: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>[N]o man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.</blockquote> | |

| − | + | Religious freedom would be the first liberty guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution’s [[Bill of Rights]], which begins by declaring, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof." This was the first time in history that a nation would constitutionally limit itself from creating laws tending to establish a state religion. | |

| − | + | The [[French Revolution]] took a somewhat different attitude regarding the question of religious liberty. The [[Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen]] guarantees that: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law.</blockquote> | |

| − | + | While affirming the right to religious freedom, the French revolutionaries adopted a more militantly secularist path. Not only would the state reject the establishment of any particular religion, it would take a vigilant stand against religion involving itself in the political arena. The American tradition, on the other hand, tended to accept religious involvement in public debate and allowed clergymen of various faiths to serve in public office. | |

| − | + | Constitutional government became the norm throughout the world over the next century, usually with guarantees of religious freedom. Unlike the American model, however, many European and colonial governments supported a state church, while minority religious and new sects still faced disadvantages and sometimes persecution. | |

| − | + | ==The Totalitarian challenge== | |

| − | + | The advent of [[Soviet Union|Soviet]] [[communism]] presented a new threat to religious freedom, as [[Marxism-Leninism]] took a militantly [[materialism|materialistic]] and [[atheism|atheistic]] stand. Seeing religion as a tool of [[capitalism|capitalist]] oppression, Soviet communists had no compunction in destroying churches, mosques, and temples, turning them into museums of atheism, and even summarily executing clergymen and other believers by the thousands. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | During [[World War II]], [[fascism|fascist]] governments also brutally repressed religions that refused to cooperate with their nationalistic aims. [[Nazism]] added a particularly virulent brand of [[racism]] to the mix, and [[Hitler]] succeeded in murdering the majority of European [[Jew]]s before finally facing military defeat. | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==The United Nations: A new era of freedom== |

| − | + | [[Image:EleanorRooseveltHumanRights.gif|left|thumb|250px|[[Eleanor Roosevelt]] with the Spanish version of the [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]]]] | |

| + | After [[World War II]], a new hope emerged with the creation of the [[United Nations]] as bastion of [[international law]]. Its [[Universal Declaration of Human Rights]] included the seminal language mentioned in its Article 18, which also became the basis of important other documents in international law. It reads: | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance.</blockquote> | |

| − | + | The communists, led by the [[Soviet Union]], begrudgingly accepted the declaration, perhaps with the cynical attitude that it was only as powerful as the paper it was written on. The [[Islam|Muslim]] world, however, has taken more formal exception to Article 18, objecting that the [[Qur'an]] outlaws both “[[blasphemy]]” (thus limiting the expression of religious ideas) and “[[apostasy]]” (thus forbidding Muslims from changing their religion). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[Roman Catholic Church]], which had long supported repressive state churches in Europe and [[Latin America]], took a decidedly progressive turn when the [[Second Vatican Council]] in 1965 declared: | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | <blockquote>The right to religious freedom has its foundation in the very dignity of the human person. In all his activity a man is bound to follow his conscience in order that he may come to God... It follows that he is not to be forced to act in a manner contrary to his conscience. Nor, on the other hand, is he to be restrained from acting in accordance with his conscience, especially in matters of religion.</blockquote> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Today there are no exclusively Catholic state churches outside of the [[Vatican]] itself, and religious freedom for Protestant groups in majority Catholic countries is much improved, especially in Latin America. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Recent trends== | |

| + | With the demise of the [[Soviet Union]], a wave of religious freedom also swept over Eastern Europe. [[Church]]es, monasteries, and [[synagogue]]s that had been used for the state’s secular purposes were turned over to their rightful owners, and millions of believers at last felt free to worship as their consciences led them. An upsurge of interest in "new religions" (new to Russia, that is, including Protestant [[missionary]] groups) soon emerged, followed by a backlash from Orthodox churches, which influenced the state to crack down on “foreign” groups in some parts of eastern Europe and Russia. | ||

| − | + | In East Asia, the nations of [[China]], [[Laos]], [[North Korea]], and [[Vietnam]] remain under officially communist regimes that continue to repress religious freedom for those groups suspected of possible disloyalty to the state. These include Catholics loyal to the [[pope]], [[Muslim]]s, [[Tibetan Buddhism|Tibetan Buddhists]], [[Protestant]]s, and the [[Falun Gong]] movement in China; Protestants in Laos, and the [[Hao Hoa]] and [[Cao Dai]] new religious movements as well as some Christians in Vietnam. North Korea has succeeded in virtually eliminating publicly expressed religion except for a small number of official places of [[worship]] operated mainly for the benefit of [[tourism|tourists]]. | |

| − | + | Europe, with its history of warfare and fratricide among religions since the time of the [[Reformation]], continues to struggle with the question of how to treat new sects and minority religions. Solutions range from laws allowing the “liquidation” of sects in [[France]], to banning religious leaders from entering several countries, to government commissions finding that the new groups do not, after all, pose a real threat. The question of dealing with the “sects” is liable to play a significant role in the evolution of a unified European identity, as will the question of favoring certain churches over others—-such as the Catholic and Lutheran churches in Germany or the Orthodox Church in eastern Europe. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[United States]], meanwhile, faces battles over refining the finer points of religious freedom, questions such as whether it is constitutional to include “Under God” in the [[Pledge of Allegiance]] and whether or how the [[Ten Commandments]] may be displayed on government property. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Islam|Muslim]] countries continue to take exception to international standards regarding religious freedom. Imprisonment, confiscation of property, and even executions still take place for the crimes of [[blasphemy]] and [[apostasy]] in several Muslim nations. The [[genocide]] of Christian and native-religious tribal groups in southern [[Sudan]] resulted at least partly from a government policy to Islamize the region. In some countries, minority religions are left unprotected from Muslim fanatics who take literally the teaching that “infidels” may be killed and their daughters forced to became second or third wives of Muslim men. Fundamentalist movements such as the [[Taliban]] and [[al Qaeda]] threaten to impose even stricter Islamic regimes with harsh punishments against infidels and apostates. | |

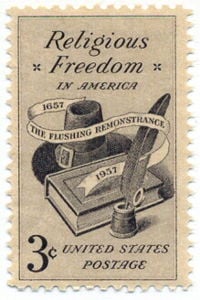

| + | [[Image:ReligiousFreedomStamp.jpg|thumb|200 px|A [[United States Post Office|U.S. postage stamp]] commemorating religious freedom]] | ||

| − | + | On the other hand, Muslim believers in places such as [[India]] are sometimes left unprotected from [[Hindu]] mobs, [[Uighur Muslims]] face widespread repression in [[China]], and Muslims in Western nations and [[Israel]] face discrimination as a result of the backlash against [[terrorism|terrorist]] attacks. | |

| − | + | ===U.S. role=== | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | As a nation formally dedicated to religious freedom and proud of its history in promoting this basic principle of human rights, the [[United States]] formally considers religious freedom in its foreign relations. The [[International Religious Freedom Act of 1998]] established the [[United States Commission on International Religious Freedom]], which investigates the records of over two hundred other nations with respect to religious freedom, and makes recommendations to submit nations with egregious records to ongoing scrutiny and possible economic sanctions. | |

| − | + | Many [[human rights]] organizations have urged the United States to be still more vigorous in imposing sanctions on countries that do not permit or tolerate religious freedom. Some critics charge that the United States policy on religious freedom is largely directed towards the rights of Christians, particularly the ability for Christian missionaries to evangelize, in other countries. | |

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| + | <references/> | ||

| − | * | + | == References== |

| + | *Beneke, Chris. ''Beyond Toleration: The Religious Origins of American Pluralism''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0195305558 | ||

| + | *Grasso, Kenneth. ''Catholicism and Religious Freedom: Contemporary Reflections on Vatican II's Declaration on Religious Liberty''. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2006. ISBN 978-0742551930 | ||

| + | *Hasson, Kevin. ''The Right to be Wrong: Ending the Culture War Over Religion in America''. New York: Encounter Books, 2005. ISBN 1594030839 | ||

| + | *Sigmund, Paul E. ''Religious Freedom and Evangelization in Latin America: The Challenge of Religious Pluralism''. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1999. ISBN 978-1570752636 | ||

| + | * U.S. Government. ''21st Century Essential Guide to Religious Freedom and Human Rights''. Progressive Management, 2005. ISBN 978-1422000441 | ||

| − | + | ==External links== | |

| − | + | All links retrieved April 11, 2024. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *[http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/instree/b3ccpr.htm International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights] – University of Minnesota Human Rights Library | |

| − | *[http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/instree/b3ccpr.htm International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights | + | *[http://www.hreoc.gov.au/Human_RightS/briefs/brief_3.html Australian Freedom of Religion and Belief] |

| − | + | *[http://www.forum18.org Forum 18: A Religious Freedom News Service] | |

| − | *[http://www.hreoc.gov.au/Human_RightS/briefs/brief_3.html | + | *[http://www.state.gov/j/drl/rls/irf/religiousfreedom/index.htm#wrapper International Religious Freedom Report for 2012] |

| − | *[http://www.forum18.org Forum 18 News Service] | ||

| − | |||

| − | *[http://www.state.gov/ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[http://www.interfaithalliance.org The Interfaith Alliance] | *[http://www.interfaithalliance.org The Interfaith Alliance] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Religion]] | [[Category:Religion]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | ||

{{Credit|128757771}} | {{Credit|128757771}} | ||

Latest revision as of 10:49, 11 April 2024

| Part of a series on |

| Freedom |

| By concept |

|

Philosophical freedom |

| By form |

|---|

|

Academic |

| Other |

|

Censorship |

Freedom of religion is a political principle guaranteeing freedom of belief and freedom of worship for individuals and groups. It is generally recognized to include related freedoms applied to the religious sphere, such as the freedoms of speech (evangelism), press (production and distribution of literature), travel for pilgrimages and meetings, and public assembly for religious purposes. Also included is the right not to follow any religion and to deny or doubt the existence of any deity.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1948, defines freedom of religion and belief as follows:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes the freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. (Article 18)

While this statement of the principles of religious freedom has yet to be established universally, it has gained wide acceptance throughout much of the world, an indication of the advance of humankind toward the realization of a world of peace.

Issues

Debates about religious freedom often center on the tension between an individual or group's right to worship (or to refrain from worship) as they please, versus the state's interest in maintaining order by imposing or favoring a particular religious culture supportive of the state. In ancient societies, the king was often also the high priest or even seen as the incarnation of a deity. Thus, religious pluralism that denied the king's religious authority constituted a direct challenge to royal power.

Related to religious freedom is the issue of religious tolerance. While tolerance represents a step forward from persecution, mere toleration of religious minorities by governments does not guarantee their religious freedom, since such groups may face significant disadvantages both legally and in terms of their treatment by society. On the other hand, absolute freedom of religious practice is problematic, since this would exempt certain religious groups from laws designed to protect citizens from such practices as human sacrifice or the destruction of "idolatrous" shrines by rival religions.

A corollary to the principle of freedom of worship is the freedom to practice religious duties such as pilgrimages, public preaching, and making converts. These duties can sometimes conflict with a state's interests. For example, pilgrimages involve freedom of travel to foreign countries, as well as the entry of foreign citizens into the country in which a particular holy site is located. Public preaching can disrupt "public order" in religiously intolerant societies where the expression of unpopular views can result in riots.

Making converts is directly threatening to the religion from which the converts are made. Where state religions are involved, the state itself may also feel directly threatened when people convert from the state religion to another faith.[1] The principle of separation of church and state was designed to prevent states from favoring one religion or a group of religions over minority religions and non-believers.

Other religious duties also sometimes run afoul of state interests. An extreme example is the practice of human sacrifice, which was common in some ancient societies. Even in cases where this might be carried out voluntarily, few would argue today that banning this practice constitutes an unnecessary abridgment of religious freedom. Female circumcision, also called female genital mutilation (FGN), is a more contentious issue, with some Muslim groups claiming this to be a religious duty and women's rights groups contending that it constitutes a crime which must be stopped by the state regardless of the opinions of those participating in the practice.

The rights of groups such as Jehovah's Witnesses and Christian Science practitioners to withhold medical attention from their children is another contentious issue involving the tension between religious freedom and the state's need to protect the health of its citizens. Some states have sought to ban groups that the state considers "dangerous," ranging from the above-named groups to more recent "sects" accused of brainwashing new members. Arguing against such policies is the principle in Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights affirming the right to change one's religion, implying that this is so even if one's new religion may be unpopular or disturbing to the majority of society.[2]

Other examples of religious duties impacting on the state are the right of workers to observe sabbaths and religious holidays without punishment by the employers, the right of minor children to choose a different religion from their parents, the right of prisoners to special religious diets, the right of religious parents to educate their children outside of state schools, the right of atheists not to invoke God in legal oaths and pledges of allegiance, and the question of religious monuments on publicly owned property.

While the basic right of freedom of worship is now generally recognized, such issues as those listed above often involve deeply-held beliefs and result in serious disagreements between governments and religious groups. Moreover, in a number of countries, even the more basic rights of religious freedom still are not upheld. In addition, governments of many nations are either unwilling or unable to prevent religiously intolerant groups from harming members of rival religions.

Ancient History

One of the earliest examples of a movement seeking religious freedom for its members is also one of the best-known stories in the Judeo-Christian tradition. Confronting the king of Egypt, the Israelite leaders Moses and Aaron demanded:

- This is what the Lord, the God of Israel, says: “Let my people go, so that they may hold a festival to me in the desert.” Pharaoh said, “Who is the Lord, that I should obey him and let Israel go?" (Exod. 5:1-3)

The story of the Exodus is cast against a background of religious and ethnic repression. The liberation of the Hebrews, together with the model of Moses confronting the Egyptian king to speak “truth to power,” has served as inspiration for both religious and political movements. It remains an archetype of the principle that one’s conscience takes precedence over any earthly authority. However, once the Israelites gained their own nation in the land of Canaan they did not grant religious freedom to native peoples but are reported in the Bible to have driven them out and later enacted legislation that repressed all religion except that approved by the Jerusalem priesthood.

The first government declaration promoting a form of religious freedom, indeed the first known human rights document of any kind, was issued in the ancient Persian Empire by its founder Cyrus the Great. Cyrus reversed the policy of his Babylonian predecessors who had destroyed local temples and removed their religious treasures. He returned these religious artifacts to their proper places and funded the restoration of important native shrines, including the Temple of Jerusalem. The so-called “Cyrus cylinder” dating from 538 B.C.E., is a remarkable archaeological find. It reads:

I Cyrus, king of the world... when I entered Babylon... Marduk the great god I sought daily to worship... As far as the region of the land of Gutium, the holy cities beyond the Tigris whose sanctuaries had been in ruins over a long period, the gods whose abode is in the midst of them, I returned to their places and housed them in lasting abodes. [These] gods... at the bidding of Marduk, the great Lord, I made to dwell in peace in their habitations, delightful abodes.

Freedom of religious worship was established as a basic principle during the Maurya Empire of ancient India by Ashoka the Great in the third century B.C.E., as encapsulated in the Edicts of Ashoka:

King Piyadasi (Ashoka), dear to the Gods, honors all sects, the ascetics (hermits) or those who dwell at home, he honors them with charity and in other ways... One must not exalt one’s creed discrediting all others, nor must one degrade these others without legitimate reasons. One must, on the contrary, render to other creeds the honor befitting them.

The right to worship freely was promoted by most ancient Indian dynasties until around 1200 C.E. The initial entry of Islam into South Asia came in the first century after the death of the Prophet Muhammad. When around 1210 C.E. the Islamic Sultanates invaded India from the northeast, the principle of freedom of religion gradually deteriorated in this part of the world.

In the West, Alexander the Great and subsequent Greek and Roman rulers generally followed a policy of religious toleration, allowing local religions to flourish as long as they also paid homage to the state religion as well. Several notable exceptions arose in relation to the Jews, as a result of their insistence that they must acknowledge their own God alone. The religious practice of circumcision was also an issue between the Greeks and the Jews, as it was considered abhorrent to the Greeks and later the Romans, who occasionally sought to suppress this Jewish practice. The early Christians, at first considered a Jewish sect, faced similar persecutions for refusing to honor the state deities.

In Early Christianity

The issue of the relation between religion and the state took clearer form in the West as Christianity came to the fore. Jesus himself became a victim of religious intolerance when, according to the New Testament, he was arrested for his religious teachings and turned over to Rome as a would-be Messiah by the high priest of Judaism and his supporters. Christians were first persecuted as a distinct group from the Jews when the Emperor Nero blamed them for the great fire of Rome in 68 C.E. In the early second century, the Emperor Trajan officially proscribed the Christian religion, and Christians suffered varying degrees of persecution. Over the next two hundred years Christians experienced repression when certain emperors insisted on their adherence to Roman state religious traditions, which many Christians suffered martyrdom to avoid.

A brighter future emerged for Christianity in the early fourth century as Constantine I issued the Edict of Milan, which declared to his governors that Christianity would thereafter be legal. The decree ordered the return of any church properties seized under previous administrations. It also guaranteed religious freedom for other religions:

It has pleased us to remove all conditions whatsoever... concerning the Christians and now any one of these who wishes to observe Christian religion may do so freely and openly, without molestation... We have also conceded to other religions the right of open and free observance of their worship for the sake of the peace of our times.

A decade later, however, Constantine embarked on a course less tolerant toward non-Christian religions, intervening on behalf of the “orthodox” party in the Arian controversy and commanding Christians not to associate with Jews. The state would now be the final arbiter in distinguishing proper doctrine from heresy, and factions within Christianity would vie for imperial support. The state changed sides several times in the Arian controversy before Theodosius I took power and declared orthodox (Catholic) Christianity to be the official state religion in 392 C.E. Christians then began using the power of the state to persecute other Christians, as well as to pressure pagans to convert to Christianity.

Ambrose of Milan set an important precedent—both for the separation of church and state and for Christian intolerance toward Judaism—when, during the reign of Theodosius I, he succeeded in causing the emperor to back down from forcing a bishop to rebuild a synagogue that had been destroyed by a Christian mob. Ambrose declared that the Christian church cannot be forced by the state to support the religion of non-Christians. Later, Ambrose’s student, Augustine of Hippo, argued successfully that the state should intervene militarily on behalf of the Roman Catholic Church against the Donatist schism in North Africa. Writing to his spiritual son Boniface, a Roman military leader in that part of the world, Augustine called for a "righteous persecution, which the Church of Christ inflicts upon the impious." However, even as he laid the foundation to justify the church’s cooperation with the state in the persecution of heretics, Augustine simultaneously struck a blow for the primacy of conscience over worldly authority:

Whosoever, therefore, refuses to obey the laws of the emperors which are enacted against the truth of God, wins for himself a great reward; but whosoever refuses to obey the laws of the emperors which are enacted in behalf of truth, wins for himself great condemnation. (A Treatise Concerning the Correction of the Donatists)

By this time, Christianity had replaced the Roman gods as a state religion. Over the next few centuries, the papacy would emerge as a bastion of orthodox resistance to state theological error. Emperors sometimes sided with heretics, and "barbarians" (who were often Arian Christians) had even sacked Rome. Facing a crisis in which the Emperor had appointed a heretical bishop to the patriarchal seat in Constantinople, Pope Gelasius I issued his famous “Two Swords” letter in 494 insisting that in spiritual matters, the church, not the state, was supreme:

There are two powers, august Emperor, by which this world is chiefly ruled, namely, the sacred authority of the priests and the royal power. Of these that of the priests is the more weighty, since they have to render an account for even the kings of men in the divine judgment. You are also aware, dear son, that while you are permitted honorably to rule over humankind, yet in things divine you bow your head humbly before the leaders of the clergy and await from their hands the means of your salvation.

The rise of Islam

Over the next thousand years church and state in the West strove for power and supremacy in both spiritual and temporal affairs. Meanwhile, a successful new religion had emerged on the scene: Islam. It quickly grew and became the dominant force in much of the former Eastern Roman Empire. Islam made no distinction between religion and the temporal state. Despite this, until the modern era, Islam was ahead of its time on the question of religious freedom. People “of the book”—namely Jews and Christians—were allowed to practice their religion in Muslim lands. The Qur'an declared:

Let there be no compulsion in religion. Truth stands out clear from Error; whoever rejects Evil and believes in Allah hath grasped the most trustworthy hand-hold, that never breaks. And Allah heareth and knoweth all things. (Qur’an 2:256)[3]

Yet, other passages in the Qur’an indicated that pagans could be enslaved or even killed if they did not accept Islam. In practice, however, religions such as Hinduism and Buddhism usually found a degree of tolerance from Islamic governments. To be sure, Christians in large numbers nevertheless suffered as Islamic armies marched on what had formerly been the Christian Empire in the East, and many were persuaded to convert to Islam by the sword. Nor can it be denied that thousands of Muslims and even many Eastern Christians were slaughtered by European Christians during The Crusades.

Medieval Europe

Jews fared better under Islamic governments than under European Christian ones. A succession of Christian kings expelled Jews from their lands. Jews were forbidden to own property and engage in certain professions. Preachers often blamed them for the Crucifixion and strongly discouraged Christians from associating with them. The first Crusade, though not directed against the Jews, nonetheless resulted in the massacre of many Jews by crusading Christians, thirsty for infidel blood. At other times, some Christian preachers overtly aroused anti-Jewish mobs to violence.

The Inquisition, originally established by papal bull in 1184, had targeted Christian heretics such as the Cathars before it turned its sights on Jews. Punishment, which was carried out by the secular government rather than the church courts, ranged from confiscation of property to prison, banishment, and, of course, public execution. Torture was not considered punishment, but a permissible tool of church investigators. Targets of the Inquisition included the Cathars of southern France, the Waldensians, the Hussites, the Knights Templar, Spiritual Franciscans, witches (the most famous being Joan of Arc), Jews, Muslims, freethinkers, and Protestants.

The Reformation

From the standpoint of freedom of belief, perhaps the most memorable moment in the epochal movement of the Reformation took place at the Diet of Worms in April 1521, when Martin Luther risked his life rather than taking the opportunity to recant his views:

Unless I am convinced by proofs from Scriptures or by plain and clear reasons and arguments, I can and will not retract, for it is neither safe nor wise to do anything against conscience. Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me.

Though the advent of the Reformation did not immediately mark a new era for religious freedom, it did enable formerly heretical practices, such as translating the Bible into the vernacular, to flourish. In 1535, the Swiss canton of Geneva became Protestant, but the Protestants often proved as intolerant of differences of opinion as the Catholics.

As Europe witnessed a series of wars in which religion played a key role, a seesaw struggle between Protestantism and Catholicism was also evident in England when Mary I of England returned that country briefly to the Catholic fold in 1553. However, her half-sister, Elizabeth I of England was to restore the Church of England in 1558.

In the Holy Roman Empire, Charles V agreed to tolerate Lutheranism in 1555 at the Peace of Augsburg. Each state was to take the religion of its prince, but within those states, there was not necessarily religious tolerance. Citizens of other faiths could relocate to a more hospitable environment. In 1558, the Transylvanian Diet of Turda declared free practice of both the Catholic and Lutheran religions, but prohibited Calvinism. Ten years later, in 1568 the Diet extended the freedom to all religions, declaring that "It is not allowed to anybody to intimidate anybody with captivity or expulsion for his teaching." The Edict of Turda is considered by mostly Hungarian historians as the first legal guarantee of religious freedom in the Christian Europe.

In France, although peace was made between Protestants and Catholics at the Treaty of Saint Germain in 1570, persecution continued, most notably in the Saint Bartholomew's Day Massacre on August 24, 1572, in which many Protestants throughout France were killed. It was not until the converted Protestant prince Henry IV of France came to the throne that religious tolerance was formalized in the Edict of Nantes in 1598. It would remain in force for over 80 years until its revocation in 1685 by Louis XIV of France. Intolerance remained the norm until the French Revolution, when state religion was abolished and all church property confiscated.

In 1573, the Warsaw Confederation formalized in the newly formed Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth the freedom of religion that had a long tradition in the Kingdom of Poland.

However, intolerance of dissident forms of Protestantism continued, as evidenced by the exodus of the Pilgrims who sought refuge, first in Holland, and ultimately in America, founding the Plymouth Colony in Massachusetts in 1620. William Penn, the founder of Philadelphia was involved in a case which had a profound effect upon future American law and that of England. A jury refused to convict William Penn of preaching a Quaker sermon, which was illegal. Even though the jury was imprisoned for their acquittal, they stood by their decision and helped establish freedom of religion. The Puritans in England, on the other hand, would soon demonstrate a more intolerant brand of Protestantism during the reign of Oliver Cromwell in the mid-seventeenth century.

Westphalia: A turning point

The Peace of Westphalia, signed in 1648, afforded international protections to religious groupings on the continent. It marked a turning point in the history of religious freedom in the West and affirmed that:

There shall be a Christian and Universal Peace, and a perpetual, true, and sincere Amity, between his Sacred Imperial Majesty [the Holy Roman Emperor], and his most Christian Majesty [of France]; as also, between all and each of the Allies... That this Peace and Amity be observ’d and cultivated with such a Sincerity and Zeal, that each Party shall endeavour to procure the Benefit, Honour and Advantage of the other; that thus on all sides they may see this Peace and Friendship in the Roman Empire, and the Kingdom of France flourish, by entertaining a good and faithful Neighbourhood.

The bloody warfare between Catholics and Protestants in England, meanwhile, brought to the fore thinkers such as John Locke, whose Essays of Civil Government and Letter Concerning Toleration played a significant role in the Glorious Revolution of 1688 and later in the American Revolution. Locke wrote:

The care of souls cannot belong to the civil magistrate, because his power consists only in outward force; but true and saving religion consists in the inward persuasion of the mind, without which nothing can be acceptable to God. And such is the nature of the understanding, that it cannot be compelled to the belief of anything by outward force. Confiscation of estate, imprisonment, torments, nothing of that nature can have any such efficacy as to make men change the inward judgment that they have framed of things.

Constitutional guarantees

Locke’s ideas on the primacy of conscience over both church and state were to be further enshrined in the American Declaration of Independence, written by Thomas Jefferson in 1776. Another of Jefferson's works, the 1779 Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, proclaimed:

[N]o man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.

Religious freedom would be the first liberty guaranteed in the U.S. Constitution’s Bill of Rights, which begins by declaring, "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof." This was the first time in history that a nation would constitutionally limit itself from creating laws tending to establish a state religion.

The French Revolution took a somewhat different attitude regarding the question of religious liberty. The Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen guarantees that:

No one shall be disquieted on account of his opinions, including his religious views, provided their manifestation does not disturb the public order established by law.

While affirming the right to religious freedom, the French revolutionaries adopted a more militantly secularist path. Not only would the state reject the establishment of any particular religion, it would take a vigilant stand against religion involving itself in the political arena. The American tradition, on the other hand, tended to accept religious involvement in public debate and allowed clergymen of various faiths to serve in public office.

Constitutional government became the norm throughout the world over the next century, usually with guarantees of religious freedom. Unlike the American model, however, many European and colonial governments supported a state church, while minority religious and new sects still faced disadvantages and sometimes persecution.

The Totalitarian challenge

The advent of Soviet communism presented a new threat to religious freedom, as Marxism-Leninism took a militantly materialistic and atheistic stand. Seeing religion as a tool of capitalist oppression, Soviet communists had no compunction in destroying churches, mosques, and temples, turning them into museums of atheism, and even summarily executing clergymen and other believers by the thousands.

During World War II, fascist governments also brutally repressed religions that refused to cooperate with their nationalistic aims. Nazism added a particularly virulent brand of racism to the mix, and Hitler succeeded in murdering the majority of European Jews before finally facing military defeat.

The United Nations: A new era of freedom

After World War II, a new hope emerged with the creation of the United Nations as bastion of international law. Its Universal Declaration of Human Rights included the seminal language mentioned in its Article 18, which also became the basis of important other documents in international law. It reads:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, either alone or in community with others and in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance.

The communists, led by the Soviet Union, begrudgingly accepted the declaration, perhaps with the cynical attitude that it was only as powerful as the paper it was written on. The Muslim world, however, has taken more formal exception to Article 18, objecting that the Qur'an outlaws both “blasphemy” (thus limiting the expression of religious ideas) and “apostasy” (thus forbidding Muslims from changing their religion).

The Roman Catholic Church, which had long supported repressive state churches in Europe and Latin America, took a decidedly progressive turn when the Second Vatican Council in 1965 declared:

The right to religious freedom has its foundation in the very dignity of the human person. In all his activity a man is bound to follow his conscience in order that he may come to God... It follows that he is not to be forced to act in a manner contrary to his conscience. Nor, on the other hand, is he to be restrained from acting in accordance with his conscience, especially in matters of religion.

Today there are no exclusively Catholic state churches outside of the Vatican itself, and religious freedom for Protestant groups in majority Catholic countries is much improved, especially in Latin America.

Recent trends

With the demise of the Soviet Union, a wave of religious freedom also swept over Eastern Europe. Churches, monasteries, and synagogues that had been used for the state’s secular purposes were turned over to their rightful owners, and millions of believers at last felt free to worship as their consciences led them. An upsurge of interest in "new religions" (new to Russia, that is, including Protestant missionary groups) soon emerged, followed by a backlash from Orthodox churches, which influenced the state to crack down on “foreign” groups in some parts of eastern Europe and Russia.

In East Asia, the nations of China, Laos, North Korea, and Vietnam remain under officially communist regimes that continue to repress religious freedom for those groups suspected of possible disloyalty to the state. These include Catholics loyal to the pope, Muslims, Tibetan Buddhists, Protestants, and the Falun Gong movement in China; Protestants in Laos, and the Hao Hoa and Cao Dai new religious movements as well as some Christians in Vietnam. North Korea has succeeded in virtually eliminating publicly expressed religion except for a small number of official places of worship operated mainly for the benefit of tourists.

Europe, with its history of warfare and fratricide among religions since the time of the Reformation, continues to struggle with the question of how to treat new sects and minority religions. Solutions range from laws allowing the “liquidation” of sects in France, to banning religious leaders from entering several countries, to government commissions finding that the new groups do not, after all, pose a real threat. The question of dealing with the “sects” is liable to play a significant role in the evolution of a unified European identity, as will the question of favoring certain churches over others—-such as the Catholic and Lutheran churches in Germany or the Orthodox Church in eastern Europe.

The United States, meanwhile, faces battles over refining the finer points of religious freedom, questions such as whether it is constitutional to include “Under God” in the Pledge of Allegiance and whether or how the Ten Commandments may be displayed on government property.

Muslim countries continue to take exception to international standards regarding religious freedom. Imprisonment, confiscation of property, and even executions still take place for the crimes of blasphemy and apostasy in several Muslim nations. The genocide of Christian and native-religious tribal groups in southern Sudan resulted at least partly from a government policy to Islamize the region. In some countries, minority religions are left unprotected from Muslim fanatics who take literally the teaching that “infidels” may be killed and their daughters forced to became second or third wives of Muslim men. Fundamentalist movements such as the Taliban and al Qaeda threaten to impose even stricter Islamic regimes with harsh punishments against infidels and apostates.

On the other hand, Muslim believers in places such as India are sometimes left unprotected from Hindu mobs, Uighur Muslims face widespread repression in China, and Muslims in Western nations and Israel face discrimination as a result of the backlash against terrorist attacks.

U.S. role

As a nation formally dedicated to religious freedom and proud of its history in promoting this basic principle of human rights, the United States formally considers religious freedom in its foreign relations. The International Religious Freedom Act of 1998 established the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, which investigates the records of over two hundred other nations with respect to religious freedom, and makes recommendations to submit nations with egregious records to ongoing scrutiny and possible economic sanctions.

Many human rights organizations have urged the United States to be still more vigorous in imposing sanctions on countries that do not permit or tolerate religious freedom. Some critics charge that the United States policy on religious freedom is largely directed towards the rights of Christians, particularly the ability for Christian missionaries to evangelize, in other countries.

Notes

- ↑ State religions vary on this issue. For example, in some Islamic states converting from Islam is a capital offense, as is proselytizing among Muslims. On the other hand, the official Church of England, for example, allows other faiths to preach freely and there is no legal penalty for converting from the state religion. Other European societies provide a preferred status for state-approved religions, putting smaller or less approved groups at a disadvantage.

- ↑ The UN Human Rights Commission has specifically affirmed that smaller and newer religions, and not just well established ones, are covered by Article 18. Indeed it is these groups that often face the greatest threat of persecution by an intolerant majority.

- ↑ Qur'an in English Translation by Yusuf Ali. Retrieved May 23, 2017.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beneke, Chris. Beyond Toleration: The Religious Origins of American Pluralism. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0195305558

- Grasso, Kenneth. Catholicism and Religious Freedom: Contemporary Reflections on Vatican II's Declaration on Religious Liberty. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 2006. ISBN 978-0742551930

- Hasson, Kevin. The Right to be Wrong: Ending the Culture War Over Religion in America. New York: Encounter Books, 2005. ISBN 1594030839

- Sigmund, Paul E. Religious Freedom and Evangelization in Latin America: The Challenge of Religious Pluralism. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 1999. ISBN 978-1570752636

- U.S. Government. 21st Century Essential Guide to Religious Freedom and Human Rights. Progressive Management, 2005. ISBN 978-1422000441

External links

All links retrieved April 11, 2024.

- International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights – University of Minnesota Human Rights Library

- Australian Freedom of Religion and Belief

- Forum 18: A Religious Freedom News Service

- International Religious Freedom Report for 2012

- The Interfaith Alliance

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.