Freedom of the press

| Part of a series on |

| Freedom |

| By concept |

|

Philosophical freedom |

| By form |

|---|

|

Academic |

| Other |

|

Censorship |

Freedom of the press (or press freedom) is the guarantee by a government of free public press for its citizens and their associations, extended to members of news gathering organizations, and their published reporting. It also extends to news gathering and processes involved in obtaining information for public distribution. Not all countries are protected by a bill of rights or the constitutional provision pertaining to Freedom of the Press.

With respect to governmental information, a government distinguishes which materials are public and which are protected from disclosure to the public based on classification of information as sensitive, classified, or secret and being otherwise protected from disclosure due to relevance of the information to protecting the national interest. Many governments are also subject to sunshine laws or freedom of information legislation that are used to define the ambit of national interest.

Freedom of the press, like freedom of speech, is not absolute; some limitations are always present both in principle and in practice. The press exercises enormous power and influence over society, and has commensurate responsibility. Journalists have access to more information than the average individual, thus the press has become the eyes, ears, and voice of the public. In this sense it has been suggested that the press functions as the "Fourth Estate," an important force in the democratic system of checks and balances. Thus, freedom of the press is seen as an advance in achieving human rights for all, and contributing to the development of a world of peace and prosperity for all. The caveat is that those who work in the media are themselves in need of ethical guidelines to ensure that this freedom is not abused.

Basic principles and criteria

In developed countries, freedom of the press implies that all people should have the right to express themselves in writing or in any other way of expression of personal opinion or creativity. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights adopted December 10, 1948, states: "Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas through any media regardless of frontiers." The concept of freedom of speech is often covered by the same laws as freedom of the press, thereby giving equal treatment to media and individuals.

There are a number of non-governmental organizations that judge the level of press freedom around the world according to various criteria. Reporters Without Borders considers the number of journalists murdered, expelled, or harassed, and the existence of a state monopoly on television and radio, as well as the existence of censorship and self-censorship in the media, and the overall independence of media as well as the difficulties that foreign reporters may face. Freedom House likewise studies the more general political and economic environments of each nation in order to determine whether relationships of dependence exist that limit in practice the level of press freedom that might exist in theory.

Coming with these press freedoms is a sense of responsibility. People look to the media as a bulwark against tyranny, corruption, and other ill forces within the public sphere. The media can be seen as the public's voice of reason to counter the powerful mechanisms of government and business. The responsibilities of the press also include an untiring adherence to the truth. Part of what makes the press so important is its potential for disseminating information, which if false can have hugely detrimental impacts on society. For this reason, the press is counted on to uphold ideals of dogged fact checking and some sense of decency, rather than publishing lurid, half-true stories.

The media as a necessity for the government

The notion of the press as the fourth branch of government is sometimes used to compare the press (or media) with Montesquieu's three branches of government, namely an addition to the legislative, the executive, and the judiciary branches. Edmund Burke is quoted to have said: "Three Estates in Parliament; but in the Reporters' Gallery yonder, there sat a Fourth estate more important far than they all."

The development of the Western media tradition is rather parallel to the development of democracy in Europe and the United States. On the ideological level, the first advocates of freedom of the press were the liberal thinkers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. They developed their ideas in opposition to the monarchist tradition in general and the divine right of kings in particular. These liberal theorists argued that freedom of press was a right claimed by the individual and grounded in natural law. Thus, freedom of the press was an integral part of the individual rights promoted by liberal ideology.

Freedom of the press was (and still is) assumed by many to be a necessity to any democratic society. Other lines of thought later argued in favor of freedom of the press without relying on the controversial issue of natural law; for instance, freedom of expression began to be regarded as an essential component of the social contract (the agreement between a state and its people regarding the rights and duties that each should have to the other).

History

World history has a number of notable moments for the freedom of the press. Some examples are outlined below. Before freedom of the press became commonplace, however, journalists relied on different authorities for their right to practice. In some countries, such as England, the press relied on a license of the king. Even today, many countries do not have established freedom of the press. In some countries, such as China, media are official outlets of the government and must not stray too far from accepted government doctrine. Other press outlets are religious mouthpieces and likewise hold views close to those of their sponsoring religions.

England

The English revolution of 1688 resulted in the supremacy of Parliament over the Crown and, above all, the right of revolution. The main theoretical inspiration behind Western liberalism was John Locke. In his view, having decided to grant some of his basic freedoms in the state of nature (natural rights) to the common good, the individual placed some of his rights in trusteeship with the government. A social contract was entered into by the people, and the Sovereign (or government) was instructed to protect these individual rights on behalf of the people, argued Locke in his book, Two Treatises of Government.

Until 1694, England had an elaborate system of licensing. No publication was allowed without the accompaniment of a government-granted license. Fifty years earlier, at a time of civil war, John Milton wrote his pamphlet Areopagitica. In this work Milton argued forcefully against this form of government censorship and parodied the idea, writing, "when as debtors and delinquents may walk abroad without a keeper, but unoffensive books must not stir forth without a visible jailer in their title." Although at the time it did little to halt the practice of licensing, it would be viewed later a significant milestone in press freedom.

Milton's central argument was that the individual is capable of using reason and distinguishing right from wrong, good from bad. In order to be able to exercise this rational right, the individual must have unlimited access to the ideas of his fellow humankind in ‚Äúa free and open encounter.‚ÄĚ From Milton‚Äôs writings developed the concept of ‚Äúthe open market place of ideas:" When people argue against each other, the good arguments will prevail. One form of speech that was widely restricted in England was the law of seditious libel that made criticizing of the government a crime. The King was above public criticism and statements critical of the government were forbidden, according to the English Court of the Star Chamber. Truth was not a defense to seditious libel because the goal was to prevent and punish all condemnation of the government.

John Stuart Mill approached the problem of authority versus liberty from the viewpoint of a nineteenth century utilitarian: The individual has the right of expressing himself so long as he does not harm other individuals. The good society is one in which the greatest number of persons enjoy the greatest possible amount of happiness. Applying these general principles of liberty to freedom of expression, Mill states that if one silences an opinion, one may silence the truth. The individual freedom of expression is therefore essential to the well-being of society.

Mill’s application of the general principles of liberty is expressed in his book On Liberty:

If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and one, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.

Germany

The dictatorship of Adolf Hitler largely suppressed freedom of the press through Joseph Goebbels' Propaganda Ministry. As the Ministry's name implies, propaganda did not carry the negative connotations that it does today (or did in the Allied countries); how-to manuals were openly distributed by that same ministry explaining the craft of effective propaganda. The Ministry also acted as a central control-point for all media, issuing orders as to what stories could be run and what stories would be suppressed. Anyone involved in the film industry‚ÄĒfrom directors to the lowliest assistant‚ÄĒhad to sign an oath of loyalty to the Nazi Party, due to opinion-changing power Goebbels perceived movies to have. (Goebbels himself maintained some personal control over every single film made in Nazi Europe.) Journalists who crossed the Propaganda Ministry were routinely imprisoned or shot as traitors.

India

The Indian Constitution, while not mentioning the word "press," provides for "the right to freedom of speech and expression" (Article 19(1) a). However this right is subject to restrictions under subclause (2), whereby this freedom can be restricted for reasons of "sovereignty and integrity of India, the security of the State, friendly relations with foreign States, public order, preserving decency, preserving morality, in relation to contempt of court, defamation, or incitement to an offence." Laws such as the Official Secrets Act and Prevention of Terrorism Act[1] (PoTA) have been used to limit press freedom. Under PoTA, a person could be detained for up to six months for being in contact with a terrorist or terrorist group. PoTA was repealed in 2006, but the Official Secrets Act 1923 continues.

For the first half-century of independence, media control by the state was the major constraint on press freedom. Indira Gandhi famously stated in 1975, that All India Radio is "a Government organ, it is going to remain a Government organ…."[2] With the liberalization starting in the 1990s, private control of media has burgeoned, leading to increasing independence and greater scrutiny of government. Organizations like Tehelka and NDTV have been particularly influential, for example in bringing about the resignation of powerful Haryana minister Venod Sharma.

United States

John Hancock was the first person to write newspapers in the British colonies in North America, published "by authority," that is, under license from and as the mouthpiece of the colonial governors. The first regularly published newspaper was the Boston News-Letter of John Campbell, published weekly beginning in 1704. The early colonial publishers were either postmasters or government printers, and therefore unlikely to challenge government policies.

The first independent newspaper in the colonies was the New-England Courant, published in Boston by James Franklin beginning in 1721. A few years later, Franklin's younger brother, Benjamin, purchased the Pennsylvania Gazette of Philadelphia, which became the leading newspaper of the colonial era.

During this period, newspapers were unlicensed, and able freely to publish dissenting views, but were subject to prosecution for libel or even sedition if their opinions threatened the government. The notion of "freedom of the press" that later was enshrined in the United States Constitution is generally traced to the seditious libel prosecution of John Peter Zenger by the colonial governor of New York in 1735. In this instance of jury nullification, Zenger was acquitted after his lawyer, Andrew Hamilton, argued to the jury (contrary to established English law) that there was no libel in publishing the truth. Yet even after this celebrated case, colonial governors and assemblies asserted the power to prosecute and even imprison printers for publishing unapproved views.

During the American Revolution, a free press was identified by Revolutionary leaders as one of the elements of liberty that they sought to preserve. The Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) proclaimed that "the freedom of the press is one of the greatest bulwarks of liberty and can never be restrained but by despotic governments." Similarly, the Constitution of Massachusetts (1780) declared, "The liberty of the press is essential to the security of freedom in a state: It ought not, therefore, to be restrained in this commonwealth." Following these examples, the First Amendment to the United States Constitution restricted Congress from abridging the freedom of the press and the closely associated freedom of speech.

John Locke’s ideas had inspired both the French and American revolutions. Thomas Jefferson wanted to unite the two streams of liberalism, the English and the French schools of thought. His goal was to create a government that would provide both security and opportunity for the individual. An active press was essential as a way of educating the population. In order to be able to work freely, the press must be free from control by the state. Jefferson was a person who himself suffered great calumnies of the press. Despite this, in his second inaugural address, he proclaimed that a government that could not stand up under criticism deserved to fall:

No experiment can be more interesting than that we are now trying, and which we trust will end in establishing the fact, that man may be governed by reason and truth. Our first object should therefore be, to leave open to him all avenues of the truth.

In 1931, the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Near v. Minnesota used the Fourteenth Amendment to apply the freedom of the press to the States. Other notable cases regarding free press are:

- New York Times Co. v. United States: The Supreme Court upheld the publication of the Pentagon Papers, which was a collection of top secret documents regarding the United States' planning of the Vietnam War that former state department official Daniel Ellsberg leaked to the press.

- New York Times Co. v. Sullivan: The Court decided that in order for written words to be libel, it must be, first of all, false. It must also be published with the deliberate intent to ruin someone's reputation.

In Branzburg v. Hayes (1972), the Court placed limits on the ability of the Press to refuse a subpoena from a grand jury by claiming freedom of the press. The issue decided in the case was whether a reporter could refuse to "appear and testify before state and Federal grand juries" by claiming such appearance and testimony "abridges the freedom of speech and press guaranteed by the First Amendment." The 5-4 decision was that such a protection was not provided by the First Amendment.

Implications of new technologies

Many of the traditional means of delivering information are being slowly superseded by the increasing pace of modern technological advance. Almost every conventional mode of media and information dissemination has a modern counterpart that offers significant potential advantages to journalists seeking to maintain and enhance their freedom of speech. A few simple examples of such phenomena include:

- Terrestrial television versus satellite television: Whilst terrestrial television is relatively easy to manage and manipulate, satellite television is much more difficult to control as journalistic content can easily be broadcast from other jurisdictions beyond the control of individual governments. An example of this in the Middle East is the satellite broadcaster Al Jazeera. This Arabic language media channel operates out of the relatively liberal state of Qatar, and often presents views and content that are problematic to a number of governments in the region and beyond. However, because of the increased affordability and miniaturization of satellite technology (dishes and receivers) it is simply not practicable for most states to control popular access to the channel.

- Web-based publishing (such as blogging) vs. traditional publishing: Traditional magazines and newspapers rely on physical resources (offices, printing presses, and so forth) that can easily be targeted and forced to close down. Web-based publishing systems can be run using ubiquitous and inexpensive equipment and can operate from any jurisdiction.

- Voice over Internet protocol (VOIP) vs. conventional telephony: Although conventional telephony systems are easily tapped and recorded, modern VOIP technology can employ sophisticated encryption systems to evade central monitoring systems. As VOIP and similar technologies become more widespread they are likely to make the effective monitoring of journalists (and their contacts and activities) a very difficult task for governments.

Naturally, governments are responding to the challenges posed by new media technologies by deploying increasingly sophisticated technology of their own (a notable example being China's attempts to impose control through a state run internet service provider that controls access to the Internet) but it seems that this will become an ever increasingly difficult task as nimble, highly motivated journalists continue to find ingenious, novel ways to exploit technology and stay one step ahead of the generally slower moving government institutions that they necessarily do battle with.

Status of press freedom worldwide

Worldwide press freedom index

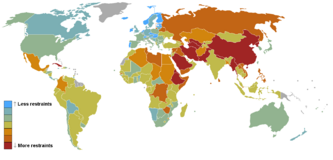

Every year, the Reporters Without Borders (RWB) organization establishes a ranking of countries in terms of their freedom of the press. The list is based on responses to surveys sent to journalists that are members of partner organizations of the RWB, as well as related specialists such as researchers, jurists, and human rights activists. The survey asks questions about direct attacks on journalists and the media as well as other indirect sources of pressure against the free press, such as pressure on journalists by non-governmental groups. RWB is careful to note that the index only deals with press freedom, and does not measure the quality of journalism.

In 2003, the countries where press was the most free were Finland, Iceland, Netherlands, and Norway.

In 2004, apart from the above countries, Denmark, Ireland, Slovakia, and Switzerland were tied at the top of the list, followed by New Zealand and Latvia. The countries with the least degree of press freedom were ranked with North Korea having the worst, followed by Burma, Turkmenistan, People's Republic of China (mainland only), Vietnam, Nepal, Saudi Arabia, and Iran.

Non-democratic states

According to Reporters Without Borders, more than a third of the world's people live in countries where there is no press freedom. Overwhelmingly, these people live in countries where there is no system of democracy or where there are serious deficiencies in the democratic process.

Freedom of the press is an extremely problematic concept for most non-democratic systems of government since, in the modern age, strict control of access to information is critical to the existence of most non-democratic governments and their associated control systems and security apparatus. To this end, most non-democratic societies employ state-run news organizations to promote the propaganda critical to maintaining an existing political power base and suppress (often very brutally, through the use of police, military, or intelligence agencies) any significant attempts by the media or individual journalists to challenge the approved "government line" on contentious issues. In such countries, journalists operating on the fringes of what is deemed to be acceptable will very often find themselves the subject of considerable intimidation by agents of the state. This can range from simple threats to their professional careers (firing, professional blacklisting) to death threats, kidnapping, torture, and assassination.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ South Asia Terrorism Portal, The Prevention of Terrorism Act 2002. Retrieved September 28, 2007.

- ‚ÜĎ PUCL Bulletin, Freedom of the Press.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cornwell, Nancy. Freedom of the Press: Rights and Liberties under the Law. ABC-CLIO, 2004. ISBN 1851094717

- Harrison, Maureen. Freedom of the Press Decisions of the United States Supreme Court. Excellent Books, 1996. ISBN 1880780100

- LeMay, Craig. Exporting Press Freedom. Routledge, 2007. ISBN 0765803593

- Smith, Jeffery. Printers and Press Freedom: The Ideology of Early American Journalism. Oxford University Press, 1990. ISBN 0195064739

- Smith, Jeffery. War and Press Freedom: The Problem of Prerogative Power. Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 019509946X

- Starr, Paul. The Creation of the Media: Political Origins of Modern Communications. New York: Basic Books, 2004. ISBN 0465081932

External links

All links retrieved April 11, 2024.

- International Freedom of Expression Exchange- Monitors press freedom around the world.

- The Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.