Ethnocentrism

Ethnocentricity is the tendency to look at the world primarily from the perspective of one's own ethnic culture. People often feel ethnocentric while experiencing during what some call culture shock.

Various researchers study ethnocentricism as it pertains to their specialized fields. This article covers anthropology, political science and especially sociology.

Definition

The term ethnocentrism was coined by William Graham Sumner, a social evolutionist and professor of Political and Social Science at Yale University. He defined it as the viewpoint that “one’s own group is the center of everything,” against which all other groups are judged. Ethnocentrism often entails the belief that one's own race or ethnic group is the most important and/or that some or all aspects of its culture are superior to those of other groups. Within this ideology, individuals will judge other groups in relation to their own particular ethnic group or culture, especially with concern to language, behaviour, customs, and religion. These ethnic distinctions and sub-divisions serve to define each ethnicity's unique cultural identity.

Anthropologists such as Franz Boas and Bronislaw Malinowski argued that any human science had to transcend the ethnocentrism of the scientist. Both urged anthropologists to conduct ethnographic fieldwork in order to overcome their ethnocentrism. Boas developed the principle of cultural relativism and Malinowski developed the theory of functionalism as tools for developing non-ethnocentric studies of different societies. The books The Sexual Life of Savages, by Malinowski, Patterns of Culture by Ruth Benedict and Coming of Age in Samoa by Margaret Mead (two of Boas's students) are classic examples of anti-ethnocentric anthropology.

Usage

In political science and public relations, not only have academics used the concept to explain nationalism, but activists and politicians have used labels like ethnocentric and ethnocentrism to criticize national and ethnic groups as being unbearably selfish — or at best, culturally biased (see cultural bias).

Nearly every religion, "race," or nation feels it has aspects which are uniquely valuable. (This tendency is humorously illustrated in the romantic comedy My Big Fat Greek Wedding, in which the heroine's father perpetually exalts Greek culture: "Give me any word, and I'll show you how it derives from Greek roots." "Oh, yeah, how about kimono?")

Other examples abound: Toynbee notes that Ancient Persia regarded itself the center of the world and viewed other nations as increasingly barbaric according to their degree of distance. China's very name is composed of ideographs meaning "center" and "country" respectively, and traditional Chinese world maps show China in the center. It's also important to note that it wasn't just China that bought into this idea. At the height of the Chinese empire, the Japanese, Koreans, Vietnamese, and Thai also believed China to be the center of the universe and referred to China as the middle kingdom. To this day, Japan, Korea, and Viet Nam still refer to China as the middle kingdom. England defined the world's meridians with itself on the center line, and to this day, longitude is measured in degrees east or west of Greenwich, thus establishing as fact an Anglo-centrist's worldview. Native American tribal names often translate as some variant on "the people"; other tribes were labeled with often pejorative names. The United States has traditionally conceived of itself as having a unique role in world history; famously characterized by President Abraham Lincoln as "the last, best hope of Earth," an outlook known as American exceptionalism.

The Japanese word for foreigner ("gaijin") can also mean "outsiders," and Japanese do not normally use the term to describe themselves when visiting other countries. It also excludes those native to the country where the speaker is. For a Japanese tourist in New York, gaijin are not Japanese tourists or New Yorkers, but those of other nationalities visiting New York.

In the United States foreigners or immigrants that are not considered residents are called "aliens" and in the case they do not hold a legal status within the country they are called "illegal aliens". The connotation of the word does not only suggest pure ethnocentrism but is in some sense a distancing language used between an American citizen and an immigrant or visitor.

Psychological underpinnings of ethnocentrism

The psychological underpinning of ethnocentrism appears to be assigning to various cultures higher or lower status or value by the ethnocentric person who then assumes that the culture of higher status or value is intrinsically better than other cultures. The ethnocentric person, when assigning the status or value to various cultures, will automatically assign to their own culture the highest status or value.

Ethnocentrism is a natural result of the observation that most people are more comfortable with and prefer the company of people who are like themselves, sharing similar values and behaving in similar ways. It is not unusual for a person to consider that what ever they believe is the most appropriate system of belief or that how ever they behave is the most appropriate and natural behavior.

A person who is born into a particular culture and grows up absorbing the values and behaviors of the culture will develop patterns of thought reflecting the culture as normal. If the person then experiences other cultures that have different values and normal behaviors, the person finds that the thought patterns appropriate to their birth culture and the meanings their birth culture attaches to behaviors are not appropriate for the new cultures. However, since a person is accustomed to their birth culture it can be difficult for the person to see the behaviors of people from a different culture from the viewpoint of that culture rather than from their own.

The ethnocentric person will see those cultures other than their birth culture as being not only different but also wrong to some degree. The ethnocentric person will resist or refuse the new meanings and new thought patterns since they are seen as being less desirable than those of the birth culture.

The ethnocentric person may also adopt a new culture, repudiating their birth culture, considering that the adopted culture is somehow superior to the birth culture.

Tribal and familial groups are often seen to dominate in economic settings where transaction costs are high. Examples include the crime syndicates of Russia, Sicily, and the United States, prison gangs, and the diamond trade (Salter 2002).

Throughout history, warring factions have been composed of fairly homogeneous ethnic groups. Ethnic strife is seen to dominate the landscape in many parts of the world even to this day. Evolutionary psychology posits that the reason for these groupings stems from the alignment of interests among members of these groups due to their genetic similarity. Independent of evolutionary psychology, observers such as Shelby Steele have suggested that ethnocentrism is a mainstay of any modern society, and in cases such as the white and black population in the US, programs such as affirmative action serve only to relieve the moral consciences of the white population. People like Steele harbor respect for vocal racists, as they, unlike the rest of the population, are able to reveal their honest feelings regarding race and ethnicity.

Types of ethnocentrism

American Exceptionalism

American exceptionalism, a term coined by Alexis de Tocqueville in 1831, has been historically referred to as the perception that the United States differs qualitatively from other developed nations, because of its unique origins, national credo, historical evolution, and distinctive political and religious institutions.1 American exceptionalism refers to the belief that the United States holds a special place in the world as a result of its unique history and ideals focused on personal and economic freedom, and is therefore a hope for humanity.

Believers in American Exceptionalism support its validity by stating that there are many ways that the United States clearly differs from the European world from which it emerged, as well as other countries in the globe. The term does not always imply a qualitative superiority, rather it emphasizes the uniqueness.

Proponents of American exceptionalism argue that the United States is unique in that it was founded on a set of republican ideals, rather than on a common heritage, ethnicity, or ruling elite. In the formulation of President Abraham Lincoln in his Gettysburg Address, America is a nation "conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal". In this view, being American is inextricably connected with loving and defending freedom and equal opportunity. Critics argue that American policy in these conflicts was more motivated by economic or military self-interest than an actual desire to spread these ideals. Indeed the United States is by no means the only country founded as a republic with such ideals, although it was perhaps the first such country: Brazil and the French republic are examples.

Proponents of American exceptionalism also assert that the "American spirit" or the "American identity" was created at the frontier (following Frederick Jackson Turner's Frontier Thesis), where rugged and untamed conditions gave birth to American national vitality. Other nations that had long frontiers—such as Russia, Canada and Australia, did not allow individualistic pioneers to settle there, and did not experience the same psychological and cultural impact.

Among some United States citizens “American exceptionalism” has come to suggest a moral superiority of the United States to other nations. Some claim that “American exceptionalism” in this sense is merely an excuse by Americans to view the world in an ethnocentric manner.

Causes and History

Puritans ideology had the largest influence on English colonists in the new world. The Puritan belief system was often a cross between strict predestination and a looser theology of Divine Providence. They believed that God had chosen them to lead the other nations of the earth. Puritan leader John Winthrop believed that the Puritan community of New England should serve as a model for the rest of the world. These deep Puritan values have remained a part of national identity, which may account for the fact that members of the Religious Right are often proponents of American Exceptionalism.

Following the Puritan ideology, the intellectuals of the American Revolution expressed beliefs similar to American Exceptionalism. They were the first to state that America is more than just an extension of Europe, instead it was a new land with unlimited potential and that it had outgrown its British mother country.

The idea of Manifest Destiny also did much to establish American Exceptionalism. First used by Jackson Democrats in the 1840's, it put forth the idea of expanding the country from coast to coast. It was also revived in the 1890's at the beginning of United States imperialism to justify international expansion. The term refers to expanding the United States because of the superior moral values and ethics associated with American ideals. The idea of manifest destiny purports that it is the duty of the United States to expand their way of life to areas of the world that would greatly benefit from the American way of life. Even though the term dropped out of use in the early 20th century, it continues to have an influence of policy and politics in the United States to modern times.

The Cold War was often conveyed in the media as a battle between the American way of life and tyranny, as examplified by Communism. This sentiment stemmed from the difference between America and the European powers in the 19th century. It was used again to put America's capitalist economy at odds with communism.

The United States was often seen as exceptional because of unlimited immigration policies and the vast resources of land and land incentivization programs during much of the 19th century. Even though those programs are for the most part in the distant past, popular attitudes within the United States often link patriotism and nationalism to them; many hold the view that the country is unique today because of what was done back then.

Eurocentrism

Eurocentrism is a type of ethnocentrism which places emphasis on European culture and the western world at the expense of other cultures. Eurocentrism often involved claiming cultures that were not white or European as being such, or denying their existence at all.

Assumptions of European superiority started during the period of European Imperialism, which started in the 16th century and reached its peak in the 19th century. During this period Europeans were exploring new lands such as Africa, and The Americas, and observed the societies that existed on these lands were largely based on farming, hunting and herding. The Europeans considered these societies to be primative in comparison to their progressive rapidly growing society. Europeans began to identify these other societies as primative, and concluded that Europe was the only place in the world that had reached the final stage of societal development.It was thus thought to be uniquely responsible for the scientific, technological and cultural achievements that constitute the modern world. Europe saw itself as a model for the modernization and technological advancement of the world as a whole.

By the 19th century it was a widespread theory that European advancement had occurred because of racial superiority, which in turn provided justification for slavery and other political and economic exploitation. Throughout the era of European Imperialism, Europeans colonized Australia, New Zealand and the Americas. Because a majority of the populations of these areas can trace their roots back to Europe, Eurocentric education typically provided in these areas, and inhabitants of these areas were raised primarily with European customes.

The practice of divine right of kings was also widespread in many European nations, which resulted in absolutism. This divine right stated that kings were ordained by God, and this right was even accepted by the kings themselves, encouraging them to go over the heads of their close advisors in the name of God. Indeed, anyone opposing the king could be declared an enemy of God. This shaped the rule of European countries, as the people living in the king's domain focused their lives on God and his chosen in the land, the kings. This led to several European countries declaring religious and spiritual superiority over other nations and increased the populations idea of being closer to God than others in the world without a chosen king.

Examples of Purported Eurocentrism

- The European miracle theory of Europe's rise to its current economic and political position has often been criticised for Eurocentrism.

- Cartesian maps have been designed throughout known history to center the northwestern part of Europe (most notably Great Britain) in the map.

- The regional names around the world are named in honor of European travelers and are in orientation of a Eurocentric worldview. Middle East describes an area slightly east of Europe. The Orient or Far East is east of Europe, whereas the West is Western Europe.

- World History taught in European schools frequently teaches only the history of Europe and the United States in detail, with only brief mention of events in Asia, Africa and Latin America.

- Western accounts of the history of mathematics are often considered Eurocentric in that they do not acknowledge major contributions of mathematics from other regions of the world, such as Indian mathematics, Chinese mathematics and Islamic mathematics. The invention of calculus is one such example.

Challenging Eurocentric models

During the same period that European writers were claiming paradigmatic status for their own history, European scholars were also beginning to develop a knowledge of the histories and cultures of other peoples. In some cases the locally established histories were accepted, in other cases new models were developed, such as the Aryan invasion theory of the origin of Vedic culture in India, which has been criticised for having at one time been modelled in such a way as to support claims for European superiority. At the same time the intellectual traditions of Eastern cultures were becoming more widely known in the West, mediated by figures such as Rabindranath Tagore. By the early 20th century some historians such as Arnold J. Toynbee were attempting to construct multi-focal models of world civilizations.

At the same time, non-European historians were involved in complex engagements with European models of history as contrasted with their own traditions. Historical models centering on China, Japan, India and other nations existed within those cultures, which to varying degrees maintained their own cultural traditions, though countries that were directly controlled by European powers were more affected by eurocentric models than were others. Thus Japan absorbed Western ideas while maintaining its own cultural identity, while India under British rule was subjected to a highly Anglocentric model of history and culture.

Even in the nineteenth century anti-colonial movements had developed claims about national traditions and values that were set against those of Europe. In some cases, as with China, local cultural values and traditions were so powerful that Westernisation did not overwhelm long-established Chinese attitudes to its own cultural centrality. In contrast, countries such as Australia defined their nationhood entirely in terms of an overseas extension of European history. It was, until recently, thought to have had no history or serious culture before colonization. The history of the native inhabitants was subsumed by the Western disciplines of ethnology and archaeology. Nationalist movements appropriated the history of native civilizations in South and Central America such as the Mayans and Incas to construct models of cultural identity that claimed a fusion between immigrant and native identity.

Indian Nationalism

Indian nationalism refers to the political and cultural expression of patriotism by peoples of India, of pride in the history and heritage of India, and visions for its future. It also refers to the consciousness and expression of religious and ethnic influences that help mould the national consciousness.

Nationalism describes the many underlying forces that moulded the Indian independence movement, and strongly continue to influence the politics of India, as well as being the heart of many contrasting ideologies that have caused ethnic and religious conflict in Indian society. It should be noted that, although controversial, Indian nationalism often imbibes the consciousness of Indians that prior to 1947, India embodied the broader Indian subcontinent.

It must be noted that in Indian English, there is no difference between patriotism and nationalism, and both the words are used interchangeably; nationalism does not have a negative connotation in India, as it does in much of Europe and North America.

The Indian civilization, its leaders and those who admired the culture and civilization of this country are a source of nationalist sentiment to its people and those who identify themselves with the Indian culture.

Beliefs of Nationalism

The core of Indian nationalism lies in the belief that the Indian civilization is one of the most ancient and influential in history. A strictly abridged set of mentions highlighting the ancient nature of the Indian civilization is given below:-

- India is the home to Hinduism, the oldest religious practice in history.

- Indus Valley civilization, the third oldest civilization in recorded history and the most advanced civilization of its time is central to Indian nationalism.

- Ancient Indian town of Taxila was home to the Takshashila University, the world's oldest university.

- Ayurveda, the world's oldest science of medicine originated in India.

- Ancient India was the site of Mehrgarh, the oldest human village settlement in recorded history and the base of later Indian towns and cities.

- India is the birthplace of ancient laguages like Harrappan, predating the hieroglyphs in Egypt, these undeciphered inscriptions were written as far back as 4th millennium B.C.E.

- India is home to many Indo-European languages, the most prominent in India being Sanskrit. Sanskrit dates back to 3500 B.C.E. makeing it one of the oldest Indo European languages.

- India is one of the cradles of mathematics, the Indian civilization is credited with mathematical inventions including zero, the decimal number system, algebra, trigonometry and calculus. Indians such as Bhaskaracharya calculated the time taken by the earth to orbit the Sun hundreds of years before the astronomer Smart. According to his calculation, the time taken by the Earth to orbit the Sun was 365.258756484 days. The value of "pi" was first calculated by the Indian mathematician Baudhayana, and he explained the concept of what is known as the Pythagorean theorem. He discovered this in the 8th-7th centuries B.C.E., long before the European mathematicians.

- India is credited with the first known work on economics, Arthashastra (literally the science of material gain in Sanskrit), written by the prime minister Chanakya of the Mauryan Empire

- The Rigveda of Hinduism was composed between roughly 1500–1300 B.C.E., making it one of the world's oldest religious texts.

- The very ancient practice of Yoga, which includes practices for spirtual enlightment, martial traditions, exercise and conditioning, curing diseases and ailments, learning and concentration originated in India. This practice is dated back to thousands of years according to the insciptions found in the Indus Valley civilization.

- India is the birthplace of one the two major schools of religions in the world, the Dharmic religions, the other school being that of the Abrahamic religions. The Dharmic religions include Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism. India is also the present home of the 14th and current Dalai Lama, his holiness Lama Tenzin Gyatso, the Buddhist equivalent of the Pope.

- India was the birthplace of the Buddhist monk Bodhidharma, credited for establishing martial traditions into the Shaolin temple of China and giving birth to the tradition of Chinese martial arts. The arts later spread to Japan, giving rise to many martial practices including Jujutsu and Judo.

The belief that India is one of the cradles of human civilization is one of the greatest reasons of pride and Indian nationalism. This sentiment may catch new momentum if the archealogical survey near Dwarka completes the unearthing of an civilization which might be the oldest in human history, thereby making India the cradle of human civilization.

Japanocentrism

Japanocentrism is the ethnocentric belief that Japan is, or should be, at the center of the world in one way or another. This may manifest itself domestically as the persecution and marginalization of non-Japanese, or globally as the pursuit of Japanese economic, cultural, or political hegemony.

The first historical expressions of Japanocentrism may be found in the treatment of Ainu, whom the Japanese perceived as uncivilized and unable to use land productively (see terra nullius). These attitudes, still somewhat common today, facilitated the gradual appropriation of Ainu farmlands and the relegation of Ainu to northerly areas. In many circles, Ainu are still viewed as noble savages, best suited to a wild, foraging existence, in spite of the fact that Ainu have traditionally been a settled, agrarian people.

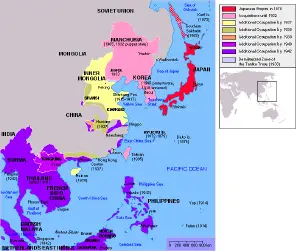

Japan was, for most of its history, divided between scores of regional warlords. Its geographical isolation and political instability resulted in a culture that was both insular and expansionistic. During the Meiji period, Japan became an industrialized power, capable of extending its influence beyond its borders. Japan was arguably the first non-European nation to possess this capability, and following the defeat of Russia in the Russo-Japanese War, Japan was virtually unopposed in East Asia.

The Japanese colonial period was brief, but intense. Between 1931 and 1945, Japan conquered a vast Asian empire, much of it seized from Western colonialists. The Japanese introduced the concept of a Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, whereby Asian nations would join together and be freed from Western colonial influence. Naturally, the linchpin of this scheme was the military dominance of the Empire of Japan. Many people in Japan continue to characterize Japanese wartime actions as counter-colonial measures, undertaken to liberate Asian peoples from European domination. The Yasukuni Shrine, for instance, publishes a pamphlet stating that the war was "...a really tragic thing to happen, but it was necessary in order for us to protect the independence of Japan and to prosper together with Asian neighbors." The refusal of many Japanese to admit to wrong-doing is a continuing source of tension between Japan and its neighbors, especially China and South Korea.

Japan's devestating defeat in WWII put an end to its imperial ambitions, but its post-war economic boom returned it to economic dominance in East Asia. As an ally of the United States, it held a privileged trading position, not to mention a massive strategic advantage. For many years the only significant liberal power in East Asia, Japan enjoyed an unchallenged central position in the Asian economy for decades. Even with the rise of the East Asian Tigers in the 1960s and the collapse of Japan's bubble economy in the early 1990s, Japan has remained at the heart of the Pacific economic scene. The Tokyo Stock Exchange remains a major factor in the Asian (and worldwide) economy. As the Japanese economy recovers its strength, it faces competition from China (both the PRC and Taiwan), South Korea, Indonesia, Malaysia, and other erstwhile uncompetitive economies.

Its prosperous but turbulent economy, along with the pressures of globalization and a low birth rate, have made Japan increasingly dependent on foreign workers and international cooperation. Its corporate culture, which has long favored protectionism, job security, and close cooperation with government, has strained to adjust to unfamiliar conditions. A central focus of Japan's corporate culture has traditionally been the preservation of Japanese culture, by such means as strict immigration controls. A recent influx of Korean and Taiwanese nationals into the workforce, though necessary to remedy the labor shortage, has met with major resistance at all levels of society. The presence of these so-called sangokujin (三国人; "third country nationals") has been characterized as a disproportionate source of criminal activity. Foreign laborers, particularly the Korean Zainichi, are regularly accused of disloyalty and even sedition. Shintaro Ishihara, while addressing members of the Japanese Self-Defense Force, once remarked that "With Sankokujin and foreigners repeating serious crimes, we should prepare ourselves for possible riots that may be instigated by them at the outbreak of an earthquake." Ishihara's comment should not be construed to represent the attitude of the average Japanese, although similar, less extreme opinions are common across the political spectrum. Earlier, in 1986, Prime minister Yasuhiro Nakasone had gained notoriety for proclaiming that Japan was successful because it did not have ethnic minorities, like the United States. He then clarified his comments, stating that he meant to congratulate the US on its economic success despite the presence of "problematic" minorities.

The belief that Japan has a central role to play in world politics, whether as a bulwark against Western hegemony or as a force in its own right, remains a central issue in Japanese politics, particularly for right-wing nationalists. The rise of the People's Republic of China as a global power has only intensified many of these feelings, as many Japanese now view their country as a check on Chinese power in the region.

Japanese Self-Image

Like most languages, Japanese has many terms to refer to outsiders and foreigners. Japanese, however, is remarkable for a rich lexicon of terms to specifically distinguish between Japanese and non-Japanese people and things. For example, the well-known term gaijin (外人), often translated as "foreigner", would be more accurately translated as "someone who is not Japanese, Chinese or Korean", since, unlike the English term, it is applied absolutely, not relatively. Japanese tourists in New York, for instance, might refer to New Yorkers, but never themselves, as gaijin. If a Japanese referred to himself as a gaijin, it would most likely be in an ironic sense. This is true of all words beginning with the kanji gai- (外), which literally means "outside". A more polite term, more common in modern discourse, is gaikokujin (外国人), which literally means "outside country person".

Within Japan (and consequently, throughout the world), the study of the origin of the Japanese people and their language is often deeply entangled with Japanocentric and counter-Japanocentric ideas and assumptions, many of which are politically motivated. This has led to a climate in which new theories are often quickly labeled either "pro-Japanese" or "anti-Japanese". Many Japanese are reluctant to accept that their language could be related to another extant language, particularly that of a long-time rival. Hence, conjectures linking the Japanese and Korean languages, such as the Altaic theory, generally receive little exposure in Japan, and are often dismissed out of hand as anti-Japanese propaganda. Many are reluctant to accept that a close genetic relationship exists between Japanese and neighboring Asian peoples. Indeed, for some very conservative Japanese, the mere suggestion that the Japanese people originated on the Asian mainland is viewed as insulting.

The animistic religion of Japan, Shintoism, involves the worshipping of the spirits found in every object and organism. Animals, houses, lakes, land, and even small toys and trinkets have a spirit, called Kami. It was at one point the primary religion of Japan, but since the second World War, some of its practices have fallen out of use or have changed meanings or significance. The Japanese Emperor, the Tenno, was declared to be a divine descendant of Amaterasu, the sun-goddess who was the most widely worshipped in Japan. Because the Emperor was said to be the descendant of Amaterasu, the Emperor was said to be a Kami on Earth with divine providence. Thus, the Japanese valued their Imperial family, because they felt a connection to their Kami through the Tenno. After World War Two, pressure from Western civilizations forced the Japanese emperor to renounce his divine status, proving a severe blow to Japanocentric ideals. The imperial family still remains deeply involved in Shinto ceremonies that unify Japan. Shinto itself does not require declaration or enforcement to be part of the religion, so there are still many who believe the renouncement of the Tenno's divine status was a mere political move, keeping Shinto ideals intact in the Imperial family.

Sinocentrism

Sinocentrism is any ethnocentric perspective that regards China to be central or unique relative to other countries. In pre-modern times, this took the form of viewing China as the only civilization in the world, and foreign nations or ethnic groups as "barbarians". In modern times, this can take the form of according China significance or supremacy at the cost of other nations in the world.

Critics of this theory allege that "Sinocentrism" is a poorly construed portrayal of China designed to incite anti-Chinese sentiment. According to this view, China has been generally peaceful throughout its history: with rare exceptions, China is said never to have made any forceful attempts to invade or colonize other nations. China's territorial expansion is attributed to ethnic groups such as the Mongols and Manchus, not the Han Chinese. However, in modern times, such ethnic groups are now regarded as equally part of the Chinese nation in the People's Republic of China, under the pluralistic ideal of Zhonghua Minzu.

Similarly, China is said not to have forced other civilizations to conform to its standards. Many of its neighbors - Korea and Japan included - willingly emulated China during these ancient times because they recognized elements of Chinese civilization as being worthy of emulation. Many foreign scholars - such as the Koreans who invented metal movable type - were given equal honors in Chinese courts. Marco Polo and the early Jesuits were treated with a great deal of respect and admiration for their skills despite having different personal beliefs.

Doubts have also been expressed about the use of "Sinocentrism" as a catch-all term for explaining China's interactions with the rest of the world. Subjective mentalities explain less than the realities of the Chinese strategic situation, in particular its need to control and defend its frontiers and deal with surrounding territories. What some have regarded as a sense of cultural and moral superiority was often merely an attempt to limit and control contact between foreigners and Chinese. For instance, the Qing Emperors tended to mistrust the loyalty of their Chinese subjects and their exclusionary policy against the Europeans was probably motivated by fear that the latter might cause problems among their subjects. As in any country, Chinese foreign policy should be seen within the context of domestic political imperatives.

The Sinocentric system

The Sinocentric system was a hierarchical system of international relations that prevailed in East Asia before the adoption of the Westphalian system in modern times.

At the center of the system stood China, ruled by the dynasty that had gained the Mandate of Heaven. This 'Celestial Empire' (神州 shénzhōu), distinguished by its Confucian codes of morality and propriety, regarded itself as the only civilization in the world; the Emperor of China (huangdi) was regarded as the only legitimate Emperor of the entire world (lands all under heaven or 天下 tianxia).

Identification of the heartland and the legitimacy of dynastic succession were both essential aspects of the system. Originally the center was synonymous with the Central Plain, an area that was expanded through invasion and conquest over many centuries. The dynastic succession was at times subject to radical changes in interpretation, such as the period of the Southern Song when the ruling dynasty lost the traditional heartland to the northern barbarians.

Outside the center were several concentric circles. Local ethnic minorities were not regarded as 'foreign countries' but were governed by their own leaders (土司 tusi), subject to recognition by the Emperor, and were exempt from the Chinese bureaucratic system.

Outside this circle were the tributary states which offered tribute (朝貢) to the Chinese Emperor and over which China exercised suzerainty. Under the Ming, when the tribute system entered its heyday, these states were classified into a number of groups. The southeastern barbarians (category one) included some of the major states of East and Southeast Asia, such as Korea, Japan, the Ryukyu Kingdom, Annam, Cambodia, Vietnam, Siam, Champa, and Java. A second group of southeastern barbarians covered countries like Sulu, Malacca, and Sri Lanka. Many of these are independent states in modern times. In addition, there were northern barbarians, northeastern barbarians, and two large categories of western barbarians (from Shanxi, west of Lanzhou, and modern-day Xinjiang), none of which have survived into modern times as separate states.

The system was complicated by the fact that some tributary states had their own tributaries. Laos was a tributary of Vietnam and the Ryukyu Kingdom paid tribute to both China and Japan.

Beyond the circle of tributary states were countries in a trading relationship with China. The Portuguese, for instance, were allowed to trade with China from leased territory in Macau but never entered the tributary system.

Under this scheme of international relations, only China had an Emperor or Huangdi (皇帝), who was the Son of Heaven; other countries only had Kings or Wang (王). (See Chinese sovereign). The Japanese use of the term Emperor or 'tennō' (天皇) for the ruler of Japan was a subversion of this principle. Significantly, the Koreans still refer to the Japanese Emperor as a King, conforming with the traditional Chinese usage.

While Sinocentrism tends to be identified as a politically inspired system of international relations, in fact it possessed an important economic aspect. The Sinocentric tribute and trade system provided Northeast and Southeast Asia with a political and economic framework for international trade. Under the tribute-trade system, articles of tribute (貢物) were presented to the Chinese emperor. In exchange, the emperor presented the tributary missions with return bestowals (回賜). Special licences were issued to merchants accompanying these missions to carry out trade. Trade was also permitted at land frontiers and specified ports. This sinocentric trade zone was based on the use of silver as a currency with prices set by reference to Chinese prices.

The political aspect of this system is that countries wishing to trade with China were required to submit to a suzerain-vassal relationship with the Chinese sovereign. After investiture (冊封) of the ruler, the emperor permitted missions to China to pay tribute.

The Sinocentric model was not seriously challenged until contact with the European powers in the 18th and 19th century, in particular the Opium War. This was mainly due to the fact that China did not come into direct contact with any of the major empires of the pre-modern period. For example, trade and diplomatic contact with the Roman Empire, and later, the Eastern Roman Empire, was usually via proxies in the form of Persians.

The Sinocentric model of political relations came to an end in the 19th century when China was overwhelmed militarily by European nations. The ideology suffered a further blow when Japan, having undergone the Meiji Restoration, defeated China in the First Sino-Japanese War. As a result, China adopted the Westphalian system of equal independent states. In modern Chinese foreign policy, the PRC is associated with the Non-Aligned Movement, and has repeatedly stated that it will never seek hegemony (永不称霸).

Culturally, one of the most famous attacks on Sinocentrism and its associated beliefs was made by the author Lu Xun in The True Story of Ah Q, satirizing the ridiculous way in which the protagonist claimed 'spiritual victories' despite being humiliated and defeated.

While China has renounced claims to superiority over other nations, some argue that China never really completely abandoned Sinocentrism and that a sinocentric view of history lies behind many modern Chinese constructs of history and self-identity.

Some claim elements of Sinocentrism have been identified in China's recent relations with Japan and Korea. In 2004, Chinese scholars identified the ancient kingdom of Goguryeo, which included southern Manchuria and northern Korea, should be regarded as a part of the history of China when its capital was in modern-day Manchuria, and a part of the history of Korea when its capital was in modern-day Korea. This caused an outcry among some Koreans who claimed Goguryeo as part of their history.

Conclusion

Ethnocentrism is a lense through which people examine other cultures. A person may compare morals, ethics, history, and religion from a foreign country to their own country and decide that their own nations practices are superior. This is the formation of an ethnocentric thought process. The opposite to this idea is cultural relativism, the idea of viewing another culture with no preconceived notions or judgments. Ethnocentrism establishes the ideas of a "proper" living, and that these other countries in comparison do not measure up to the "proper" way of living.

Ethnocentrism can be seen as the backbone to stereotypes. Ideas such as the work ethic of a particular culture, or lack of morals in another culture, stem from the idea in ethnocentrism that ones own culture is above a foreign culture in many regards. The scope of ethnocentrism can also be held responsible for instigating racism in different societies. Ethnocentric persepctives are not merely limited to different nations, indeed different races in the same society often look at other races from an ethnocentric point of view.

Perhaps the evolution of globalization can lead to a decrease in ethnocentric evaluations. With the world getting more connected, and with people having greater access to information than at any other time, it is possible to dispel many cultural myths in coming generations, fostering a better universal understanding of how different cultures function and maintain themselves. Indeed, ethnocentrism is not a term that needs to be around forever.

References and Notes

- Allinson, G. Japan’s Postwar History, Cornell University Press, 2nd edition, 2004. ISBN 0801489121

- Bourdaghs, M. The Dawn That Never Comes: Shimazaki Toson and Japanese Nationalism, Columbia University Press, 2003. ISBN 0231129807

- Hicks, G. Japan's Hidden Apartheid: The Korean Minority and the Japanese, Ashgate Publishing, 1997. ISBN 1840141689

- Ishihara, S. The Japan That Can Say No: Why Japan Will Be First Among Equals, Simon & Schuster, 1991. ISBN 0671726862

- Van Wolferen, K. The Enigma of Japanese Power: People and Politics in a Stateless Nation, Vintage, 1990. ISBN 0679728023

- Walker, B. The Conquest of Ainu Lands: Ecology and Culture in Japanese Expansion,1590-1800, University of California Press, 2001. ISBN 0520227360

- Williams, D. Defending Japan's Pacific War: The Kyoto School Philosophers and Post-White Power, Routledge, 2005. ISBN 0415323150

- Salter, F.K. 2002. Risky Transactions: Trust, Kinship, and Ethnicity. Oxford and New York: Berghahn. ISBN 1571817107

- Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, Sage Press.

- Note 1: Foreword: on American Exceptionalism; Symposium on Treaties, Enforcement, and U.S. Sovereignty, Stanford Law Review, May 1 2003, Pg. 1479

Further reading

- Dworkin, Ronald W. 1996. The Rise of the Imperial Self. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 0847682196

- Glickstein, Jonathan A. 2002. American Exceptionalism, American Anxiety: Wages, Competition, And Degraded Labor In The Antebellum United States. University Press of Virginia. ISBN 0813921155

- Hellerman, Steven L, and Andrei S. Markovits. 2001. Offside: Soccer and American Exceptionalism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 069107447X

- Kagan, Robert. 2003. Of Paradise and Power: America and Europe in the New World Order. Knopf. ISBN 1400040930

- Lipset, Seymour Martin. 1997. American Exceptionalism: A Double-Edged Sword. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393316149

- Madsen, Deborah L. 1998. American Exceptionalism. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 1578061083

- Shafer, Byron E. 1991. Is America Different? : A New Look at American Exceptionalism. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 0198277342

- Turner, Frederick Jackson. 1999. The Significance of the Frontier in American History, in Does The Frontier Experience Make America Exceptional?.

- Voss, Kim. 1994. The Making of American Exceptionalism: The Knights of Labor and Class Formation in the Nineteenth Century. Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801428823

- Wrobel, David M. 1996 (original 1993). The End Of American Exceptionalism: Frontier Anxiety From The Old West To The New Deal. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 0700605614

External links

- "The American Creed: Does It Matter? Should It Change?" Democracy's Discontent: America in Search of a Public Philosophy. From Foreign Affairs, March/April 1996

- The right to be different Debate between Grover Norquist and Will Hutton.

- The religious character of American patriotism recognizing American traditions and the questions brought up.

- Public Secrets: Geopolitical Aesthetics in Zhang Yimou’s Hero essay on Zhang Yimou.

- China puts Korean spat on the map

- Origin of Vietnam name

- The Rise of East Asia and the Withering Away of the Interstate System

- Sinocentrism or Paranoia?

- Suzerain and Vassal, or Elder and Younger Brothers: The Nature of the Sino-Burmese Historical Relationship

- The Zhuang Literati From Ming to Mid-Qing - A study of Confucianism and the acculturation of the Zhuang ethnic group

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Ethnocentrism history

- American_exceptionalism history

- Eurocentrism history

- Japanocentrism history

- Sinocentrism history

- Islamism history

- Indian_nationalism history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.