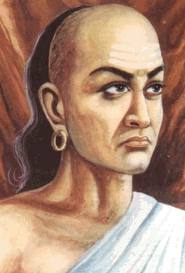

Kautilya or Chanakya (Sanskrit: à¤à¤¾à¤£à¤à¥à¤¯ CÄá¹akya) (c. 350 - 283 B.C.E.) was an adviser and a Prime Minister[1] to the first Maurya Emperor Chandragupta (c. 340-293 B.C.E.), and architect of his rise to power. According to legend, he was a professor at Taxila University when the Greeks invaded India, and vowed to expel them. He recognized the leadership qualities of young Chandragupta and guided him as he overcame the Nanda and defeated the Greek satrapies in northern India, then built an efficient government which expanded the Maurya empire over most of the Indian subcontinent (except the area south of present-day Karnataka), as well as substantial parts of present-day Afghanistan.

Chanakya is traditionally identified with Kautilya and Vishnugupta, the author of the ArthaÅhÄstra, an encyclopedic work on political economy and government.[2] Some scholars have called Chanakya "the pioneer economist of the world"[3] and the "the Indian Machiavelli."[4]

Identity

He is generally called Chanakya, but in his capacity as author of the ArthaÅhÄstra, is generally referred to as Kautilya.[5] The ArthaÅhÄstra identifies its author by the name Kautilya, except for one verse which refers to him by the name Vishnugupta.[2] One of the earliest Sanskrit literary texts to explicitly identify Chanakya with Vishnugupta was Vishnu Sarma's Panchatantra in the third century B.C.E.[2]

Not every historian accepts that Kautilya, Chanakya, and Vishnugupta are the same person. K.C. Ojha suggests that Viá¹£á¹ugupta was a redactor of the original work of Kauá¹ilya, and that the traditional identification of Viá¹£á¹ugupta with Kauá¹ilya was caused by a confusion of the editor with the original author.[2] Thomas Burrow suggests that CÄá¹akya and Kauá¹ilya may have been two different people.[5] The date of origin of the Arthahastra remains problematic, with suggested dates ranging from the fourth century B.C.E. to the third century C.E. Most authorities agree that the essence of the book was originally written during the early Mauryan Period (321â296 B.C.E.), but that much of the existing text is post-Mauryan.

Early life

Chanakya was educated at Taxila or Takshashila,[6] in present day Pakistan. The new states (in present-day Bihar and Uttar Pradesh) by the northern high road of commerce along the base of the Himalayas maintained contact with Takshasilâ and at the eastern end of the northern high road (uttarapatha) was the kingdom of Magadha with its capital city, Pataliputra, now known as Patna. Chanakya's life was connected to these two cities, Pataliputra and Taxila.

In his early years, Chanakya was tutored extensively in the Vedas; it is said that he memorized them completely at an early age. He was also taught mathematics, geography and science along with religion. At sixteen he entered the university at Taxila, where he became a teacher of politics. At that time, the branches of study in India included law, medicine, and warfare. Two of Chanakyaâs more famous students were Bhadrabhatt and Purushdutt.

Opposition to the Ruler of Nanda

At the time of Alexander's invasion, Chanakya was a teacher at Taxila University. The king of Taxila and Gandhara, Ambhi (also known as Taxiles), made a treaty with Alexander and did not fight against him. Chanakya saw the foreign invasion as a threat to Indian culture and sought to inspire other kings to unite and fight Alexander. The Mudrarakshasa of Visakhadutta as well as the Jaina work Parisishtaparvan talk of Chandragupta's alliance with the Himalayan king Parvatka, sometimes identified with Porus, a king of Punjab.[7] Porus (Parvateshwar) was the only local king who was able to challenge Alexander at the Battle of the Hydaspes River, but was defeated.

Chanakya then went further east to the city of Pataliputra (presently known as Patna, in Magadha, in the state of Bihar, India), to seek the help of Dhana Nanda, who ruled a vast Nanda Empire which extended from Bihar and Bengal in the east to eastern Punjab in the west. Although Chanakya initially prospered in his relations with Dhana Nanda, his blunt speech soon antagonized the ruler, who removed him from his official position. In all the forms of the Chanakya legend, he is thrown out of the Nanda court by the king, whereupon he swears revenge.[5]

According to the Kashmiri version of his legend, ChÄá¹akya uproots some grass because it had pricked its foot.[5]

There are various accounts of how Chanakya first made the acquaintance of Chandragupta. One account relates that Chanakya had purchased Chandragupta from Bihar, on his way back to Taxila. Another interpretation, says that while in Magadha, Chanakya met Chandragupta by chance. He was impressed by the prince's personality and intelligence, saw his potential as a military and political leader, and immediately began to train the young boy to fulfill his silent vow to expel the Greeks. An account by the Roman historian Junianus Justinus suggests that Chandragupta had also accompanied Chanakya to Pataliputra and himself was insulted by Dhana Nanda (Nandrum).

He was of humble origin, but was pushing to acquiring the throne by the superior power of the mind. When after having offended the king of Nanda by his insolence, he was condemned to death by the king, he was saved by the speed of his own feet⦠He gathered bandits and invited Indians to a change of rule.[8]

Establishment of the Mauryan Empire

Together, Chanakya and Chandragupta planned the conquest of the Nanda Empire.

The Chandraguptakatha relates that Chandragupta and Chanakya were initially rebuffed by the Nanda forces. In the ensuing war, Chandragupta was eventually able to defeat Bhadrasala, commander of Dhana Nanda's armies, and Dhana Nanda in a series of battles, ending with the siege of the capital city Kusumapura[9] and the conquest of the Nanda Empire around 321 B.C.E., founding the powerful Maurya Empire in Northern India. By the time he was twenty years old, Chandragupta had succeeded in defeating the Macedonian satrapies in India and conquering the Nanda Empire, and had founded a vast empire that extended from Bengal and Assam in the east, to the Indus Valley in the west, which he further expanded in later years. Chanakya remained at his side as Prime Minister and chief adviser, and later served his son Bindusara in the same capacity.

Legends

There are numerous legends regarding Chanakya and his relationship with Chandragupta. Thomas R. Trautmann identifies the following elements as common to different forms of the Chanakya legend:[5]

- Chanakya was born with a complete set of teeth, a sign that he would become king, which is inappropriate for a Brahmin like Chanakya. ChÄá¹akya's teeth were therefore broken and it was prophesied that he would rule through another.

- The Nanda King threw ChÄnakya out of his court, prompting ChÄnakya to swear revenge.

- ChÄnakya searched for one worthy for him to rule through, until he encountered a young Chandragupta Maurya, who was a born leader even as a child.

- ChÄnakya's initial attempt to overthrow Nanda failed, whereupon he came across a mother scolding her child for burning himself by eating from the middle of a bun or bowl of porridge rather than the cooler edge. ChÄá¹akya realized his initial strategic error and, instead of attacking the heart of Nanda territory, slowly chipped away at its edges.

- ChÄnakya betrayed his ally, the mountain king Parvata.

- ChÄnakya enlisted the services of a fanatical weaver to rid the kingdom of rebels.

Jain version

According to Jaina accounts, ChÄnakya was born in the village of Caá¹aka in the Golla district to Caá¹in and Caá¹eÅvarÄ«, a Jain Brahmin couple.[5]

According to a legend which is a later Jaina invention, while Chanakya served as the Prime Minister of Chandragupta Maurya, he started adding small amounts of poison to Chandragupta's food so that he would become accustomed to it, in order to prevent the Emperor from being poisoned by enemies. One day the queen, Durdha, who was nine months pregnant, shared the Emperorâs food and died. Chanakya determined that the baby should not die; he cut open the belly of the queen and took out the baby. A drop (bindu in Sanskrit) of poison had passed to the baby's head, and Chanakya named him Bindusara. Bindusara later became a great king and father of the Mauryan Emperor Asoka.

When Bindusara became a youth, Chandragupta gave up the throne to his son, followed the Jain saint Bhadrabahu to present day Karnataka and settled in a place known as Sravana Belagola. He lived as an ascetic for some years and died of voluntary starvation according to Jain tradition. Chanakya remained as the Prime Minister of Bindusara. Bindusara also had a minister named Subandhu who did not like Chanakya. One day Subandhu told Bindusara that Chanakya was responsible for the murder of his mother. Bindusara confirmed the story with the women who had nursed him as an infant, and became very angry with Chanakya.

It is said that Chanakya, on hearing that the Emperor was angry with him, thought it was time to end his life. He donated all his wealth to the poor, widows and orphans, and sat on a dung heap, prepared to die by total abstinence from food and drink. Meanwhile, Bindusara heard the full story of his birth from the nurses and rushed to beg forgiveness of Chanakya. But Chanakya would not relent. Bindusara went back and vented his fury on Subandhu, who asked for time to beg for forgiveness from Chanakya.

Subandhu, who still hated Chanakya, wanted to make sure that Chanakya did not return to the city. He arranged for a ceremony of respect, but unnoticed by anyone, slipped a smoldering charcoal ember inside the dung heap. Aided by the wind, the dung heap swiftly caught fire, and Chanakya was burned to death.

Chanakya was cremated by his grandson/disciple Radhagupta who succeeded Rakshasa Katyayan (great-grand son of Prabuddha Katyayan, who attained Nirvana during the same period as Gautama Buddha) as Prime Minister of the Maurya Empire and was instrumental in backing Ashoka to the throne. At that time there were three non-orthodox belief systems in India, Jainism, Buddhism and Ajivaka (an ascetic school similar to Jainism). Chanakya, who practiced Ajivaka, brought about the downfall of the Jaina Nandas and their coterie of Jaina ministers, backed in his political machinations by his uncle, who was a Jain, and a group of Jains.

Chandragupta Maurya converted to Jainism on abdicating his throne, which passed to his son Bindusara, an Ajivaka. Even Ashoka who became Buddhist before accession to throne, practiced Ajivaka. Later on, Ajivikism, which was the official religion of the empire for fourteen years after the Kalinga War (261 B.C.E.), declined and merged into traditional Hinduism.

Other versions

Pali legend claims that CÄá¹akka was a Brahmin from Taxila. This claimis supported by the ninth century Sanskrit play by Vishakhadatta, Mudra Rakshasa, a once popular source of Chanakya lore.[5]

A South Indian group of Brahmins in Tamil Nadu called Sholiyar or Chozhiyar, claim that Chanakya was one of them. Though this may seem improbable considering the vast distance between present day Tamilnadu in the south and Magadha in Bihar, it finds curious echos in Parishista-parvan, where Hemachandra claims that Chanakya was a Dramila. ("Dramila" is believed to be the root of the word "Dravida" by some scholars).

Works

Chanakya is credited with advising Chandragupta during the conquest of the Nanda and the defeat of the Greeks, and on the formation of a strong efficient government, which allowed the Mauryan Empire to rule almost the entire subcontinent (except the area south of present-day Karnataka), as well as substantial parts of present-day Afghanistan. He is best known, however, for his work, Arthashastra, an encyclopedic work on political economy and government, which he refers to as âthe science of punishment.â Each of its fifteen sections deals with some aspect of government, such as fiscal policies, coinage, commerce, welfare, forests, weights and measures, agriculture, law, international relations, and military strategy. The central purpose of Kautilya's doctrine was to achieve the prosperity of king and country, and to secure victory over rival neighboring states.

Kautilya identified seven factors which affected a governmentâs ability to accomplish these ends: the qualities of the king, then of his ministers, his provinces, his city, his treasure, his army, and his allies. In describing an ideal government, Kautilya articulated contemporary assumptions of political and economic theory, providing historical information about the political circumstances of the time.

Kautilya is admired for his understanding of human nature and his political wisdom, and sometimes condemned for condoning ruthlessness and treachery. He openly advised the development of an elaborate spy system reaching into all levels of society, providing detailed instruction for spies and agents, and encouraged political and secret assassination.

Two additional works are attributed to Chanakya: Nitishastra, a treatise on the ideal way of life, and Chanakya Niti, a compilation of his nitis, or policies.

Media

Chanakya, a television series directed by Chandra Prakash Dwivedi, was screened in India in 1990, to wide critical acclaim.

The diplomatic enclave in New Delhi is named Chanakyapuri in honor of Chanakya.

See also

- Magadhan Empire

- Mauryan dynasty

- Chandragupta Maurya

- Asoka Maurya

- Bindusara Maurya

- Dasaratha Maurya

- Arthashastra

Notes

- â Roger Boesche, Kautilya's ArthaÅÄstra on War and Diplomacy in Ancient India, The Journal of Military History 67 (1): 9â37. ISSN 0899-3718.

- â 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 I. W. Mabbett, The Date of the ArthaÅhÄstra, Journal of the American Oriental Society 84(2) (1964): 162â169. ISSN 0003-0279.

- â L.K. Jha, K.N. Jha, Chanakya: The pioneer economist of the world, International Journal of Social Economics 25 (2-4): 267-282.

- â Herbert H. Gowen, "The Indian Machiavelli" or Political Theory in India Two Thousand Years Ago, Political Science Quarterly 44 (2): 173-192.

- â 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Thomas R. Trautmann, Kautilya and the ArthaÅhÄstra: A Statistical Investigation of the Authorship and Evolution of the Text (Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1971).

- â Hinduism online, Chanakya Nitishastra, Chanakya-Niti. Retrieved October 20, 2007.

- â John Marshall, Taxila, 18.

- â Junianus Justinus, Historiarum Philippicarum libri XLIV, XV.4.15. Retrieved October 21, 2007.

- â Bharati Mukherjee, Kautilya's Concept of Diplomacy a New Interpretation (Columbia, MO: South Asia Books, 1976, ISBN 9780883865040).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boesche, Roger. The First Great Political Realist Kautilya and his Arthashastra. Lanham: Lexington Books, 2002. ISBN 978-0739104019.

- Chaturvedi, B.K. Kautilya's Arthashastra (science of polity). New Delhi: Diamond Books, 2006. ISBN 978-8171820795.

- Kauá¹alya, and L. N. Rangarajan. The Arthashastra. New Delhi: Penguin Books India, 1992. ISBN 978-0140446036.

- Kauá¹alya, and Tumkur Narasimhiah Ramaswamy. Essentials of Indian Statecraft; KÌautilya's Arthasastra for Contemporary Readers. New York: Asia Pub. House, 1962.

- Marshall, John. Taxila. Cambridge University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-1107615809.

- Mukherjee, Bharati. Kautilya's Concept of Diplomacy a New Interpretation. Columbia, MO: South Asia Books, 1976. ISBN 978-0883865040.

- Reddy, Sujatha. Laws of Kautilya Aá¹thaÅÄstá¹a. New Delhi: Kanishka Publishers, Distributors, 2004. ISBN 978-8173916199.

- Trautmann, Thomas R. Kauá¹ilya and the ArthaÅÄstra: A Statistical Investigation of the Authorship and Evolution of the Text. Leiden: E.J. Brill, 1971.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.