Yoga

Yoga (from the Sanskrit root yuj ("to yoke")) refers to a series of interrelated ancient Hindu spiritual practices that originated in India, where it remains a vibrant living tradition. Yoga is one of the six orthodox systems (darshans) of Indian philosophy. Its influence has been widespread among many other schools of Indian thought. In Hinduism, Yoga is seen as a system of self-realization and a means to enlightenment. It is also a central concept in Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism and has influenced other religious and spiritual practices throughout the world. The basic text of Yoga, the Yoga-sutras, is attributed to Pata√Ījali, who lived in India around 150 B.C.E.

During the twentieth century, the philosophy and practice of Yoga became increasingly popular in the West. The Yoga taught in the West as a form of physical fitness, weight control, and self-development is commonly associated with the asanas (postures) of Hatha Yoga; the deeper philosophical aspects of yoga are often ignored.

Yoga

Yoga (from the Sanskrit root yuj ("to yoke")) refers to a series of interrelated ancient Hindu spiritual practices that originated in India, where it remains a vibrant living tradition. Yoga is one of the six orthodox systems (darshans) of Indian philosophy. Its influence has been widespread among many other schools of Indian thought. In Hinduism, Yoga is seen as a system of self-realization and a means to enlightenment. It is also a central concept in Buddhism, Sikhism, Jainism and has influenced other religious and spiritual practices throughout the world. The basic text of Yoga, the Yoga-sutras, is attributed to Pata√Ījali, who lived in India around 150 B.C.E..

The ultimate goal of yoga is the attainment of liberation (Moksha) from worldly suffering and the cycle of birth and death (Samsara). Yoga entails mastery over the body, mind, and emotional self, and transcendence of desire. It is said to lead gradually to knowledge of the true nature of reality. The Yogi reaches an enlightened state where there is a cessation of thought and an experience of blissful union. This union may be of the individual soul (Atman) with the supreme Reality (Brahman), as in Vedanta philosophy; or with a specific god or goddess, as in theistic forms of Hinduism and some forms of Buddhism. Enlightenment may also be described as extinction of the limited ego, and direct and lasting perception of the non-dual nature of the universe.

Historical Origins

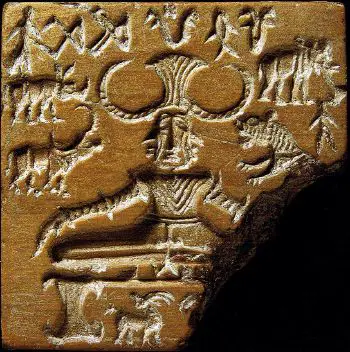

Archaeological discoveries of figurines and seals found in the Indus Valley Civilization depict what appears to be humans practicing meditation and yoga but these conclusions are merely conjectures. The earliest written accounts of yoga appear in the Rig Veda, which began to be codified between 1500 and 1200 B.C.E. In the Upanisads, the older Vedic practices of offering sacrifices and ceremonies to appease external gods gave way instead to a new understanding that humans can, by means of an inner sacrifice, become one with the Supreme Being (referred to as BrńĀhman or MńĀhńĀtman), through moral culture, restraint and training of the mind.

The Bhagavadgita (written between the fifth and second centuries B.C.E.) defines yoga as the highest state of enlightenment attainable, beyond which there is nothing worth realizing, in which a person is never shaken, even by the greatest pain.[1] In his conversation with Arjuna, Krishna distinguishes several types of "yoga," corresponding to the duties of different nature of people:

- (1) Karma yoga, the yoga of "action" in the world.

- (2) Jnana yoga, the yoga of knowledge and intellectual endeavor.

- (3) Bhakti yoga, the yoga of devotion to a deity (for example, to Krishna).

Patanjali

Authorship of the Yoga Sutras, which form the basis of the darshana called "yoga," is attributed to Patanjali (second century B.C.E.). The Raja yoga system one of the six "orthodox" Vedic schools of Hindu philosophy. The school (darshana) of Yoga is primarily Upanishadic with roots in Samkhya, and some scholars see some influence from Buddhism. The Yoga system accepts Samkhya psychology and metaphysics, but is more theistic and adds God to the Samkhya’s 25 elements of reality[2] as the highest Self distinct from other selves.[1] Ishvara (the Supreme Lord) is regarded as a special Purusha, who is beyond sorrow and the law of Karma. He is one, perfect, infinite, omniscient, omnipresent, omnipotent and eternal. He is beyond the three qualities of Sattva, Rajas and Tamas. He is different from an ordinary liberated spirit, because Ishvara has never been in bondage.

Patanjali was more interested in the attainment of enlightenment through physical activity than in metaphysical theory. Samkhya represents knowledge, or theory, and Yoga represents practice.

The Yoga Sutra is divided into four parts. The first, Samahdi-pada, deals with the nature and aim of concentration. The second, Sadhanapada explains the means to realize this concentration. The third, Vibhuitpada, deals with the supranormal powers which can be acquired through yoga, and the fourth, Kaivalyapada, describes the nature of liberation and the reality of the transcendental self.[1]

Patanjala Yoga is also known as Raja Yoga (Skt: "Royal yoga") or "Ashtanga Yoga" ("Eight-Limbed Yoga"), and is held as authoritative by all schools. The goal of Yoga is defined as 'the cessation of mental fluctuations' (cittavrtti nirodha). Chitta (mind-stuff) is the same as the three ‚Äúinternal organs‚ÄĚ of Samkhya: intellect (buddhi), ego (anhakara) and mind (manas). Chitta is the first evolute of praktri (matter) and is in itself unconscious. However, being nearest to the purusa (soul) it has the capacity to reflect the purusa and therefore appear conscious. Whenever chitta relates to or associates itself with an object, it assumes the form of that object. Purusa is essentially pure consciousness, free from the limitations of praktri (matter), but it erroneously identifies itself with chitta and therefore appears to be changing and fluctuating. When purusa recognizes that it is completely isolated and is a passive spectator, beyond the influences of praktri, it ceases to identify itself with the chitta, and all the modifications of the chitta fall away and disappear. The cessation of all the modifications of the chitta through meditation is called ‚ÄúYoga.‚ÄĚ[1]

The reflection of the purusa in the chitta, is the phenomenal ego (jiva) which is subject to birth, death, transmigration, and pleasurable and painful experiences; and which imagines itself to be an agent or enjoyer. It is subject to five kinds of suffering: ignorance (avidyńĀ), egoism (asmitńĀ), attachment (rńĀga), aversion (dveŇüa), and attachment to life coupled with fear of death (abhinivesha).

Patanjali's Yoga Sutra sets forth eight "limbs" of yoga practice:

- (1) Yama The five "abstentions:" abstention from injury through thought, word or deed (ahimsa); from falsehood (satya); from stealing (asteya); from passions and lust (brahmacharya); and from avarice (aparigraha).

- (2) Niyama The five "observances:" external and internal purification (shaucha), contentment (santosa), austerity (tapas), study (svadhyaya), and surrender to God (Ishvara-pranidhana).

- (3) Asana: This term literally means "seat," and originally referred mainly to seated positions. With the rise of Hatha yoga, it came to be used for yoga "postures" as well.

- (4) Pranayama: Control of prńĀna or vital breath

- (5) Pratyahara ("Abstraction"): "that by which the senses do not come into contact with their objects and, as it were, follow the nature of the mind."‚ÄĒVyasa

- (6) Dharana ("Concentration"): Fixing the attention on a single object

- (7) Dhyana ("Meditation") The undisturbed flow of thought around the object of meditation.

- (8) Samadhi: ‚ÄúConcentration.‚ÄĚ Super-conscious state or trance (state of liberation) in which the mind is completely absorbed in the object of meditation.

Paths of Yoga

Over the long history of yoga, different schools have emerged, and it is common to speak of each form of yoga as a "path" to enlightenment. Thus, yoga may include love and devotion (as in Bhakti Yoga), selfless work (as in Karma Yoga), knowledge and discernment (as in Jnana Yoga), or an eight-limbed system of disciplines emphasizing morality and meditation (as in Raja Yoga). These practices occupy a continuum from the religious to the scientific and they need not be mutually exclusive. (A person who follows the path of selfless work might also cultivate knowledge and devotion.) Some people (particularly in Western cultures) pursue Hatha yoga as exercise divorced from spiritual practice.

Other types of yoga include Mantra Yoga, Kundalini Yoga, Iyengar Yoga, Kriya Yoga, Integral Yoga, Nitya Yoga, Maha Yoga, Purna Yoga, Anahata Yoga, Tantra Yoga, and Tibetan Yoga, and Ashtanga Vinyasa Yoga (not to be confused with Ashtanga Yoga), a specific style of Hatha Yoga practice developed by Sri K. Pattabhi Jois.

Common to most forms of yoga is the practice of concentration (dharana) and meditation (dhyana). Dharana, according to Patanjali's definition, is the "binding of consciousness to a single point." The awareness is concentrated on a fine point of sensation (such as that of the breath entering and leaving the nostrils). Sustained single-pointed concentration gradually leads to meditation (dhyana), in which the inner faculties are able to expand and merge with something vast. Meditators sometimes report feelings of peace, joy, and oneness.

The focus of meditation may differ from school to school, e.g. meditation on one of the chakras, such as the heart center (anahata) or the third eye (ajna); or meditation on a particular deity, such as Krishna; or on a quality like peace. Non-dualist schools such as Advaita Vedanta may stress meditation on the Supreme with no form or qualities (Nirguna Brahman). This resembles Buddhist meditation on the Void.

Another element common to all schools of yoga is the spiritual teacher (guru in Sanskrit; lama in Tibetan). The role of the guru varies from school to school; in some, the guru is seen as an embodiment of the Divine. The guru guides the student (shishya or chela) through yogic discipline from the beginning. Thus, the novice yoga student should find and devote himself to a satguru (true teacher). Traditionally, knowledge of yoga‚ÄĒas well as permission to practice it or teach it‚ÄĒhas been passed down through initiatory chains of gurus and their students. This is called guruparampara.

The yoga tradition is one of practical experience, but also incorporates texts which explain the techniques and philosophy of yoga. Many modern gurus write on the subject, either providing modern translations and elucidations of classical texts, or explaining how their particular teachings should be followed. A guru may also found an ashram or order of monks; these comprise the institutions of yoga. The yoga tradition has also been a fertile source of inspiration for poetry, music, dance, and art.

When students associate with a particular teacher, school, ashram or order, this naturally creates yoga communities where there are shared practices. Chanting of mantras such as Aum, singing of spiritual songs, and studying sacred texts are all common themes. The importance of any one element may differ from school to school, or student to student. Differences do not always reflect disagreement, but rather a multitude of approaches meant to serve students of differing needs, background and temperament.

The yogi is sometimes portrayed as going beyond rules-based morality. This does not mean that a yogi is acting in an immoral fashion, but rather that he or she acts with direct knowledge of the supreme Reality. In some legends, a yogi, having amassed merit through spiritual practice, caused mischief even to the gods. Some yogis in history have been naked ascetics, such as Swami Trailanga, who greatly vexed the occupying British in nineteenth century Benares by wandering about in a state of innocence.

Hatha Yoga

Over the last century the term yoga has come to be especially associated with the postures (Sanskrit ńĀsanas) of hatha yoga ("Forced Yoga"). Hatha yoga has gained wide popularity outside of India and traditional yoga-practicing religions, and the postures are sometimes presented as entirely secular or non-spiritual in nature. Traditional Hatha Yoga is a complete yogic path, including moral disciplines, physical exercises (such as postures and breath control), and meditation, and encompasses far more than the yoga of postures and exercises practiced in the West as physical culture. The seminal work on Hatha Yoga is the Hatha Yoga Pradipika, written by Swami Svatmarama. Hatha Yoga was invented to provide a form of physical purification and training that would prepare aspirants for the higher training of Raja Yoga. In the West, however, many practice 'Hatha yoga' solely for the perceived health benefits it provides, and not as a path to enlightenment.

Yoga and Religion

In the Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, and Jain traditions, the spiritual goals of yoga are seen as inseparable from the religions of which yoga forms a part. Some yogis make a subtle distinction between religion and yoga, seeing religion as more concerned with culture, values, beliefs and rituals; and yoga as more concerned with Self-Realization and direct perception of the ultimate truth. In this sense, religion and yoga are complementary.

Some forms of yoga come replete with a rich iconography, while others are more austere and minimalist.

Buddhist Yoga

Yoga is intimately connected to the religious beliefs and practices of Buddhism and Hinduism.[3] There are however variations in the usage of terminology in the two religions. In Hinduism, the term "Yoga" commonly refers to the eight limbs as defined in the Yoga Sutras of Patanjali, which were written some time after 100 B.C.E. In the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism the term "Yoga" is used to refer to the six levels of teachings divided into Outer tantra (Kriyayoga, Charyayoga and Yogatantra) and Inner tantra (Mahayoga, Anuyoga and Atiyoga). Hindu Yoga is claimed to have had an influence on Buddhism, which is notable for its austerities, spiritual exercises, and trance states.

Many scholars have noted that the concepts dhyana and samadhi are common to meditative practices in both Hinduism and Buddhism. The foundation for this assertion is a range of common terminology and common descriptions of meditative states seen as the foundation of meditation practice in both traditions. Most notable in this context is the relationship between the system of four Buddhist dhyana states (Pali jhana) and the samprajnata samadhi states of Classical Yoga.[4]

Zen Buddhism

Zen, a form of Mahayana Buddhism, is noted for its proximity with Yoga. Certain essential elements of Yoga are important both for Buddhism in general and for Zen in particular.[5] In the west, Zen is often set alongside Yoga, the two schools of meditation display obvious resemblances.

Tibetan Buddhism

Within the various schools of Tibetan Buddhism yoga holds a central place, though not in the form presented by Patanjali or the Gita. Yoga used as a way to enhance concentration.[6]

Buddhist Yoga was introduced to Tibet from India, in the form of Vajrayana teachings as found in the Nyingma, Kagyupa, Sakyapa and Gelukpa schools of Tibetan Buddhism.

In the Nyingma tradition, practitioners progress to increasingly profound levels of yoga, starting with MahńĀ yoga, continuing to Anu yoga and ultimately undertaking the highest practice, Ati yoga. In the Sarma traditions, the Anuttara yoga class is equivalent. Other tantra yoga practices include a system of 108 bodily postures practiced with breath and heart rhythm timing in movement exercises is known as Trul khor or union of moon and sun (channel) prajna energies, and the body postures of Tibetan ancient yogis are depicted on the walls of the Dalai Lama's summer temple of Lukhang.

In the thirteenth and the fourteenth centuries, the Tibetan developed a fourfold classification system for Tantric texts based on the types of practices each contained, especially their relative emphasis on external ritual or internal yoga. The first two classes, the so-called lower tantras, are called the Kriya and the Chatya tantras; the two classes of higher tantras are the Yoga and the Anuttara Yoga (Highest Yoga).[7]

Yoga and Tantra

Yoga is often mentioned in company with Tantra. While the two have deep similarities, most traditions distinguish them from one another.

They are similar in that both amount to families of spiritual texts, practices, and lineages with origins in the Indian subcontinent. Their differences are variously expressed. Some Hindu commentators see yoga as a process whereby body consciousness is seen as the root cause of bondage, while tantra views the body as a means to understanding, rather than as an obstruction. The Hatha Yoga Pradipika is generally classified as a Hindu tantric scripture.

Tantra has roots in the first millennium C.E., is based on a more theistic concept. Almost entirely founded on Shiva and Shakti worship, Hindu tantra visualizes the ultimate Brahman as Param Shiva, manifested through Shiva (the passive, masculine force of Lord Shiva) and Shakti (the active, creative feminine force of his consort, variously known as Ma Kali, Durga, Shakti, Parvati and others). It focuses on the kundalini, a three and a half-coiled 'snake' of spiritual energy at the base of the spine that rises through the chakras until union between Shiva and Shakti (also known as samadhi) is achieved.

Tantra emphasizes mantra (Sanskrit prayers, often to gods, that are repeated), yantra (complex symbols representing gods in various forms through intricate geometric figures), and rituals that include the worship of murti (statue representations of deities) or images.

Notable Yogis

Many dedicated individuals have influenced the practice of yoga, and spread awareness of yoga throughout the world.

Ancient tradition includes Meera from the Bhakti tradition, Shankaracharya from the Jnana Yoga tradition, Patanjali, who formalized the system of Raja Yoga.

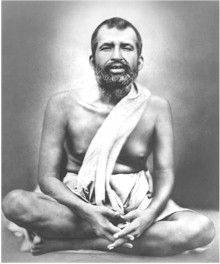

In the late 1800s, Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, a Bhakti Yogi, brought about a rebirth of yoga in India. A teacher of Advaita Vedanta, he preached that "all religions lead to the same goal." The noted Indian author Sri Aurobindo (1872 - 1950) translated and interpreted Yogic scriptures, such as the Upanishads and Bhagavad-Gita, and wrote The Synthesis of Yoga, expounding a synthesis of the four main Yogas (Karma, Jnana, Bhakti and Raja). Other Indian yogis who inspired their countrymen include Swami Rama Tirtha (1873 ‚Äď 1906), and Swami Sivananda (1887 ‚Äď 1963), founder of the Divine Life Society, who authored over three hundred books on yoga and spirituality and was a pioneer in bringing Yoga to the west. Gopi Krishna (1903 ‚Äď 1984), a Kashmiri office worker and spiritual seeker wrote best-selling autobiographical [1] accounts of his spiritual experiences.

During the early twentieth century, many yogis travelled to the west to spread knowledge of Yoga.

Swami Vivekananda, (1863 ‚Äď 1902), Ramakrishna's disciple, is well known for introducing Yoga philosophy to many in the west, as well as reinvigorating Hinduism in a modern setting during India's freedom struggle.

Swami Sivananda (1887-1963), founder of the Divine Life Society lived most of his life in Rishikesh, India. He wrote an impressive 300 books on various aspects of Yoga, religions, philosophy, spirituality, Hinduism, moral ethics, hygiene and health. He was a pioneering Yogi and throughout the world.

Paramahansa Yogananda (1893-1952), a practitioner of Kriya Yoga, taught Yoga as the binding force that reconciled Hinduism and Christianity. Yogananda founded the Self-Realization Fellowship in Los Angeles, in 1925. His book Autobiography of a Yogi continues to be one of the best-selling books on yoga.

A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada (1896 ‚Äď 1977) popularized Bhakti Yoga for Krishna in many countries through his movement, the International Society for Krishna Consciousness, (popularly known as the Hare Krishna movement) which he founded in 1966. His followers, known for enthusiastic chanting in public places, brought Bhakti Yoga to the attention of many westerners.

In 1955, the socio-spiritual organization Ananda Marga (the path of bliss) was founded by P.R. Sarkar (1921 ‚Äď 1990), also known as Shrii Shrii Anandamurti. Based on tantric yoga, his teaching emphasizes social service in the context of a political, economic and cultural theory; or ‚Äúself-realization and service to all.‚ÄĚ

Also during this period, many yogis brought greater awareness of Hatha yoga to the west. Some of these individuals include students of Sri Tirumalai Krishnamacharya, who taught at Mysore Palace from 1924 until his death in 1989; Sri K. Pattabhi Jois, B.K.S. Iyengar, Indra Devi and Krishnamacharya's son T.K.V. Desikachar.

Around the same time, the Beatles' interest in Transcendental Meditation served to make a celebrity of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi.

Modern Yoga and Yoga in the West

Modern yoga practice often includes traditional elements inherited from Hinduism, such as moral and ethical principles, postures designed to keep the body fit, spiritual philosophy, instruction by a guru, chanting of mantras (sacred syllables), breathing exercises, and stilling the mind through meditation. These elements are sometimes adapted to meet the needs of non-Hindu practitioners, who may be attracted to yoga by its utility as a relaxation technique or as a way to keep fit.

Proponents of yoga see daily practice as beneficial in itself, leading to improved health, emotional well-being, mental clarity, and joy in living. Yoga advocates progress toward the experience of samadhi, an advanced state of meditation where there is absorption in inner ecstasy. While the history of yoga strongly connects it with Hinduism, proponents claim that yoga is not a religion itself, but contains practical steps which can benefit people of all religions, as well as those who do not consider themselves religious.

During the twentieth century, the philosophy and practice of Yoga became increasingly popular in the West. The first important organization for practitioners in the United States was the Self-Realization Fellowship, founded by Paramahansa Yogananda in 1920. Instruction emphasizing both the physical and spiritual benefits of Yogic techniques is now available through a wide variety of sectarian Yoga organizations, nonsectarian classes, gymnasiums, and television programs in the United States and Europe, and through a vast library of books and educational materials.

The yoga becoming increasingly popular in the West as a form of physical fitness, weight control, and self-development is commonly associated with the asanas (postures) of Hatha Yoga, but Westerners often ignore the deeper philosophy of yoga.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Chandrahar Sharma, A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy (Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 2003, ISBN 8120803647), 169-170.

- ‚ÜĎ Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan and Charles A. Moore (eds.), A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973, ISBN 0691019584), 453.

- ‚ÜĎ Georg Feuerstein, The Yoga Tradition: Its history, literature, philosophy and practice (Boston, MA: Shambhala, 1996, ISBN 8120819233), 111.

- ‚ÜĎ Stuart Ray Sarbacker, Samadhi: The Numinous and Cessative in Indo-Tibetan Yoga (State University Press of New York, 2006, ISBN 0791465535), 77.

- ‚ÜĎ Heinrich Dumoulin, James W. Heisig, and Paul F. Knitter, Zen Buddhism: A History (India and China) (New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1994, ISBN 0028971094).

- ‚ÜĎ C. Alexander Simpkins and Annellen M. Simpkins, Simple Tibetan Buddhism: A Guide to Tantric Living (Tuttle Publishing, 2001, ISBN 0804831998).

- ‚ÜĎ John C. Huntington, Dina Bangdel, and Robert A. F. Thurman, The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art (Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2003, ISBN 1932476016), 25.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arya, Usharbudh. Philosophy of Hatha Yoga. Honesdale, PA: Himalayan International Institute of Yoga Science and Philosophy of the U.S.A., 1985. ISBN 089389088X

- Dasgupta, Surendranath. A History of Indian Philosophy, Vol. III. Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 1973. ISBN 8120804120

- Dumoulin, Heinrich. Zen Buddhism a History. Vol.1, India and China: with a new supplement on the Northern School of Chinese Zen. (Nanzan studies in religion and culture.) New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1994. ISBN 0028971094

- Feuerstein, Georg. The Shambhala Guide to Yoga. Boston, MA: Shambhala, 1996. ISBN 157062142X

- Gharote, M.L., Vijay Kant Jha, Parimal Devnath, and S.B. Sakhalkar. Encyclopaedia of Traditional Asanas. Lonavla: Lonavla Yoga Institute, 2006. ISBN 8190161725

- Ghate, Vinayak Sakharam. The VedńĀnta: A study of the BrahmasŇętras with the bhńĀsyas of S√°ŠĻĀkara, RńĀmńĀnuja, NimbńÉrka, Madhva and Vallabha. Poona: Bhandharkar Oriental Research Institute, 1960.

- Huntington, John C., Dina Bangdel, and Robert A. F. Thurman. The Circle of Bliss: Buddhist Meditational Art. Chicago: Serindia Publications, 2003. ISBN 1932476016

- Iyengar, B.K.S. Yoga: The Path to Holistic Health. London: Dorling Kindersley Pub., 2001. ISBN 0789471655

- Klostermaier, Klaus K. Hinduism: A short introduction. Oxford: Oneworld, 2000. ISBN 1851682201

- Radhakrishnan, Sarvepalli, and Charles A. Moore (eds.). A Sourcebook in Indian Philosophy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1973. ISBN 0691019584

- Sarbacker, Stuart Ray. Samadhi: The Numinous and Cessative in Indo-Tibetan Yoga. State University Press of New York, 2006. ISBN 0791465535

- Sharma, Chandrahar. A Critical Survey of Indian Philosophy. Delhi, Motilal Banarsidass, 2003. ISBN 8120803647

- Simpkins, C. Alexander, and Annellen M. Simpkins. Simple Tibetan Buddhism: A Guide to Tantric Living. Tuttle Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0804831998

External links

All links retrieved May 25, 2023.

- JOY: The Journal of Yoga investigating the philosophy, science, and spirituality of yoga.

- Yoga Teachers Training Course (TTC).

| Indian philosophy | |

|---|---|

| Topics | Logic · Idealism · Monotheism · Atheism · Problem of evil |

| ńÄstika | Samkhya ¬∑ Nyaya ¬∑ Vaisheshika ¬∑ Yoga ¬∑ Mimamsa ¬∑ Vedanta (Advaita ¬∑ Vishishtadvaita ¬∑ Dvaita) |

| NńĀstika | Carvaka ¬∑ Jaina (Anekantavada) ¬∑ Bauddha (Shunyata ¬∑ Madhyamaka ¬∑ Yogacara ¬∑ Sautrantika ¬∑ Svatantrika) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.