Marco Polo

| Marco Polo |

|---|

Marco Polo

|

| Born |

| September 15, 1254 Venice, Republic of Venice |

| Died |

| January 8, 1324 Venice, Republic of Venice |

Marco Polo (September 15, 1254 â January 8, 1324) was a Venetian trader and explorer who, with his father Niccolò and his uncle Maffeo, was one of the first Europeans to travel the Silk Road to China (then called Cathay) and visit the Great Khan of the Mongol Empire, Kublai Khan (grandson of Genghis Khan).

Although Marco Polo was not the first Westerner to reach to Far East, his journeys, chronicled in Il Milione ("The Million" or The Travels of Marco Polo), became much more widely known than those of any predecessor and popularized the East in European imagination. Subsequently, trade and commerce with China became much more significant and Chinese products found their way into European homes. Growing trade with the East would hasten the Age of Exploration, as Portuguese and Spanish seamen, most notably the Genoese navigator Christopher Columbus, sought a sea route for the lucrative trade.

Marco Polo helped to bring two different cultures into closer communication and can be considered one of the great cultural ambassadors in human history. The Polos' courage and willingness to travel to remote regions and peacefully engage with peoples of vastly different cultural and religious practices found a counterpart in the Mongol Khan's openness and generosity to the exotic strangers from distant Europe.

Voyage of Niccolò and Maffeo Polo

The Polo name originally did not belong to a family of explorers, but to a family of traders. Marco Polo's father, Niccolò (also Nicolò in Venetian) and his uncle, Maffeo (also Maffio), were prosperous merchants who traded with the East. They were partners with a third brother, named Marco il vecchio (the Elder).

In 1259, the two brothers lived in the Venetian quarter of Constantinople, where they enjoyed political privileges and tax relief because of their country's role in establishing the Latin Empire in the Fourth Crusade of 1204. But the family judged the political situation of the city precarious, so they decided to transfer their business northeast to Soldaia, a city in Crimea. Their decision proved wise. Constantinople was recaptured in 1261 by Michael Palaeologus, the ruler of the Empire of Nicaea, who promptly burned the Venetian quarter.[1] Captured Venetian citizens were blinded,[2] while many of those who managed to escape perished aboard overloaded refugee ships fleeing to other Venetian colonies in the Aegean Sea.

As their new home on the north rim of the Black Sea, Soldaia had been frequented by Venetian traders since the twelfth century. The Mongol army sacked it in 1223, but the city had never been definitively conquered until 1239, when it became a part of the newly formed Mongol state known as the Golden Horde. Searching for better profits, the Polos continued their journey to Sarai, where the court of Berke Khan, the ruler of the Golden Horde, was located. At that time, the city of Saraiâalready visited by William of Rubruck a few years earlierâwas no more than a huge encampment, and the Polos stayed for about a year. Finally, they decided to avoid Crimea, because of a civil war between Berke and his cousin Hulagu or perhaps because of the bad relationship between Berke Khan and the Byzantine Empire. Instead, they moved further east to Bukhara, in modern day Uzbekistan, where the family lived and traded for three years.

In 1264, Nicolò and Maffio joined up with an embassy sent by the Ilkhan Hulagu to his brother, the Grand Khan Kublai. In 1266, they reached the seat of the Grand Khan in the Mongol capital Khanbaliq (present day Beijing, China).

In his book, Il Milione, Marco explains how Kublai officially received the Polos and sent them backâwith a Mongol named Koeketei as an ambassador to the pope. They brought with them a letter from the khan requesting educated people to come and teach Christianity and Western customs to his people, as well as the paiza, a golden tablet a foot long and three inches wide, authorizing the holder to require and obtain lodging, horses and food throughout the great khan's dominion. Koeketei left in the middle of the journey, leaving the Polos to travel alone to Ayas in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia. From that port city, they sailed to Saint Jean d'Acre, capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem.

The long sede vacanteâbetween the death of Pope Clement IV, in 1268, and the election of Pope Gregory X, in 1271âprevented the Polos from fulfilling Kublaiâs request. As suggested by Theobald Visconti, papal legate for the realm of Egypt, in Acres for the Ninth Crusade, the two brothers returned to Venice in 1269 or 1270, waiting for the nomination of the new pope.

Voyages of Marco

Journey to Cathay and service to the khan

Maffeo and Niccolò Polo set out on a second journey with the pope's response to Kublai Khan in 1271. This time Niccolò took his son Marco, along with two friars who did not finish the voyage due to fear.

When Marco Polo arrived at Kublai Khan's court he became a favorite of the khan and was employed for 17 years and was sent on voyages and was given permission to trade freely throughout China.

In 1291, Kublai entrusted Marco with his last duty, to escort the Mongol princess Koekecin (Cocacin in Il Milione) to her betrothed, the Ilkhan Arghun. In 1293 or 1294 the Polos reached the Ilkhanate, ruled by Gaykhatu after the death of Arghun, and left Koekecin with the new Ilkhan. Then they moved to Trabzon and from that city sailed to Venice.

Il Milione

On their return from China in 1295, the family settled in Venice where they became a sensation and attracted crowds of listeners who had difficulties in believing their reports of distant China. According to a late tradition, since they did not believe him, Marco Polo invited them all to dinner one night during which the Polos dressed in the simple clothes of a peasant in China. Shortly before the crowds ate, the Polos opened their pockets to reveal hundreds of rubies and other jewels which they had received in Asia. Though they were much impressed, the people of Venice still doubted the Polos.

Marco Polo was later captured in a minor clash of the war between Venice and Genoa, or in the naval battle of Curzola, according to one tradition. He spent the few months of his imprisonment, in 1298, dictating to a fellow prisoner, Rustichello da Pisa, a detailed account of his travels in the then-unknown parts of the Far East.

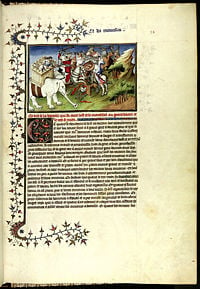

His book, Il Milione (the title comes from either "The Million," then considered a gigantic number, or from Polo's family nickname Emilione), was written in Old French and entitled Le divisament dou monde ("The Description of the World"). The book was soon translated into many European languages and is known in English as The Travels of Marco Polo. The original is lost and there are now several often-conflicting versions of the translations. The book became an instant successâquite an achievement in a time when printing was not known in Europe.

Later life

Marco Polo was finally released from captivity in the summer of 1299, and he returned home to Venice, where his father and uncles had bought a large house in the central quarter named Contrada San Giovanni Crisostomo with the company's profits.

The company continued its activities, and Marco was now a wealthy merchant. While he personally financed other expeditions, he would never leave Venice again. In 1300, he married Donata Badoer, a woman from an old, respected patrician family. Marco would have three children with her: Fantina, Bellela and Moreta. All of them later married into noble families.

Between 1310 and 1320, he wrote a new version of his book, Il Milione, in Italian. The text was lost, but not before a Franciscan friar, named Francesco Pipino, translated it into Latin. This Latin version was then translated back into the Italian, creating conflicts between different editions of the book.

Marco died in his home on January 1324, at almost 70 years old. He was buried in the Church of San Lorenzo.

Historical and cultural impact

Although the Polos were by no means the first Europeans to reach China overland (see, for example, Radhanites and Giovanni da Pian del Carpine), due to Marco's book their trip was the first to be widely known, and the best-documented until then. Marco Polo's description of the Far East and its riches inspired Christopher Columbus's decision to try to reach those lands by a western route. A heavily annotated copy of Polo's book was among the belongings of Columbus.

Legend has it that Marco Polo introduced to Italy some products from China, including ice cream, the piĂąata and pasta, especially spaghetti. However, these legends are not grounded in factâpasta on the Italian peninsula can be traced back to 400 B.C.E. through decorations found on an Etruscan tomb.

The name Marco Polo was given to a three-masted clipper ship built in Saint John, New Brunswick, in 1851. The fastest ship of her day, Marco Polo was the first ship to sail around the world in under six months. Several ships of the Italian navy were named Marco Polo, and Veniceâs airport is named in his honor.

The travels of Marco Polo are given an extended fantasy treatment in the Irish writer Donn Byrne's Messer Marco Polo, and in Gary Jennings' 1984 novel The Journeyer. He also appears as the pivotal character in Italo Calvino's novel Invisible Cities.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Hart, Henry H. Marco Polo, Venetian Adventurer. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1967.

- Larner, John. Marco Polo and the Discovery of the World. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1999. ISBN 0300079710

- Polo, Marco. The Travels of Marco Polo: The Complete Yule-Cordier Edition: Including the Unabridged Third Edition (1903) of Henry Yuleâs Annotated Translation, as Revised by Henri Cordier, Together with Cordierâs Later Volume of Notes and Addenda (1920). New York: Dover Publications, 1993. ISBN 0486275868 (v. 1), ISBN 0486275876 (v. 2).

- Wood, Frances. Did Marco Polo Go to China?. Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1996. ISBN 0813389984

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.