Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus, commonly rendered in Spanish as Crist√≥bal Col√≥n (1451 - May 20, 1506) was a Genoese-born navigator, explorer, and colonizer whose epochal voyage west across the Atlantic Ocean, in 1492, in search of a direct sea route to the Indies, established permanent European contact with the unknown lands and peoples of North and South America. Columbus' voyage, combining audacious confidence, supreme seamanship, and an explicit faith that he was called by God for the task of bringing the Christian religion to remote peoples of the world‚ÄĒhis name meant "Christ-bearer"‚ÄĒinaugurated the most profound advances in humankind's awareness of the planet, and formative interchanges among disparate cultures that would lead to the emergence of the modern world.

Columbus' voyage took place during the early decades of the European Age of Exploration, following advances in ship design and navigational instrumentation that enabled Portuguese explorers to venture down the African coastline in search of a sea route to India. By the mid-fifteenth century, the historic barrier of the Sahara had been overcome and a lucrative trade in slaves and gold provided incentive for further explorations. In 1487, Bartholomew Dias rounded the Cape of Good Hope on the southern tip of Africa, and in 1498, Vasco da Gama crossed the Indian Ocean and reached the southern tip of India. Columbus, instead, proposed to strike out directly west across the unknown Atlantic, and through tenacious determination secured the backing of the Spanish sovereigns, Ferdinand and Isabella, for the visionary voyage.

Columbus made landfall on what is thought to be the Bahamian island of San Salvador (today's Watling Island) on October 12, 1492, and explored Cuba and Hispaniola. He only reached the South American mainland on his third voyage in 1498, still believing until his death, in 1506, that he had reached the Indies. Though not the first to reach the Americas from Europe‚ÄĒNorsemen had reached Labrador around 1000 C.E. and some scholars speculate that Polynesians, Africans, and ancient Phoenicians had made earlier contact‚ÄĒColumbus launched the historic process that yielded knowledge of vast continents and complex civilizations, and his encounter with indigenous peoples began the cross-cultural fertilization that has come to be known as the "Columbian Exchange." Europeans for which Indians had no immunity.

Columbus' voyages came at a critical time of growing national imperialism and economic competition between developing nation states seeking wealth from the establishment of trade routes and colonies. Columbus founded a colony in today's Santo Domingo on the island of Hispaniola, which became the colonial headquarters for later Spanish explorations and the eventual conquest of powerful empires and tribal peoples from Mexico, the Caribbean, and South America. Columbus' engagement with largely peaceful Indians was often brutal, and his objective of Christianizing native inhabitants was callously compromised by the expedition's quest for gold and the capture and enslavement of Indians. In the decades after Columbus' voyage, Spanish Conquistadors would overthrow the Aztec and Incan civilizations through superior military technology, singular acts of treachery, and the willing support of subject populations who lived in fear of mass ritual human sacrifice and other forms of oppression. Native American populations throughout the Western hemisphere would be decimated through colonial occupation by the Spanish, Portuguese, French, and English, largely through epidemic diseases brought by The anniversary of the 1492 voyage is observed as Columbus Day throughout the Americas and in Spain. In recent years, the calamitous consequences of European colonization upon Native American life has been emphasized, while Columbus' extraordinary courage and vision, and the historic movement toward a common human destiny initiated through contact have been construed as a dated evaluation of the explorer that marginalizes the near total subjugation of Native American peoples.

Early life

According to the most widely acknowledged biographies, Columbus was born between August and October 1451, in Genoa. His father was Domenico Colombo, a middle-class wool weaver working between Genoa and Savona. His mother was Susanna Fontanarossa. Bartolomeo, Giovanni Pellegrino, and Giacomo were his brothers. Bartolomeo worked in a cartography workshop in Lisbon for at least part of his adulthood.

While information about Columbus' early years is scarce, he probably received an incomplete education. He spoke a Genoese dialect. In one of his writings, Columbus claims to have gone to the sea at the age of 10. In 1470, the Columbus family moved to Savona, where Domenico took over a tavern. In the same year, Columbus was on a Genoese ship hired in the service of René I of Anjou to support his attempt to conquer the Kingdom of Naples.

In 1473, Columbus began his apprenticeship as business agent for the important Centurione, Di Negro, and Spinola families of Genoa. Later, he allegedly made a trip to Chios, in the Aegean Sea. In May 1476, he took part in an armed convoy sent by Genoa to carry a valuable cargo to northern Europe. He docked in Bristol, Galway, in Ireland and very likely, in 1477, he was in Iceland. In 1479, Columbus reached his brother Bartolomeo in Lisbon, keeping on trading for the Centurione family. He married Filipa Moniz, daughter of the Porto Santo governor, Bartolomeo Perestrello. In 1481, his son, Diego was born.

No authentic contemporary portrait of Christopher Columbus exists. Over the years historians have presented many images that reconstruct his appearance from written descriptions. They depict him variously with long or short hair, heavy or thin, bearded or clean-shaven, stern or at ease. Columbus is described as having reddish hair which turned to white early-on in life and a reddish face typically resulting from a lighter skinned person receiving too much sun exposure.

Columbus's campaign for funding

Columbus first presented his plan for a western route to the Indies to the court of Portugal in 1485. The king's experts believed that the route would be longer than Columbus thought (the actual distance is even longer than the Portuguese believed), and they denied Columbus' request. It is probable that he made the same outrageous demands for himself in Portugal that he later made in Spain, where he went next. He tried to get backing from the monarchs Ferdinand II of Aragon and Isabella I of Castile, who, by marrying, had united the largest kingdoms of Spain and were ruling them together.

After seven years of lobbying at the Spanish court, where he was kept on a salary to prevent him from taking his ideas elsewhere, he was finally successful in 1492. Ferdinand and Isabella had just conquered Granada, the last Muslim stronghold on the Iberian peninsula, and they received Columbus in Córdoba, in the monarchs' Alcázar or castle. Isabel finally turned Columbus down on the advice of her confessor, and he was leaving town in despair, when Fernando intervened. Isabel then sent a royal guard to fetch him and Ferdinand later rightfully claimed credit for being "the principal cause why those islands were discovered."

About half of the financing was to come from private Italian investors, whom Columbus had already lined up. Financially broken from the Granada campaign, the monarchs left it to the royal treasurer to shift funds among various royal accounts on behalf of the enterprise. According to the contract that Columbus made with King and Queen, if Columbus discovered any new islands or mainland, he would:

- Be given the rank of Admiral of the Ocean Sea (Atlantic Ocean)

- Be appointed Viceroy and Governor of all the new lands

- Have the right to nominate three persons, from whom the sovereigns would choose one, for any office in the new lands

- Be entitled to 10 percent of all the revenues from the new lands in perpetuity; this part was denied to him in the contract, although it was one of his demands

- Have the option of buying one-eighth interest in any commercial venture with the new lands and receive one-eighth of the profits

The terms were extraordinary, but as his own son later wrote, the monarchs did not really expect him to return. It is important to note that many of the smears against Columbus were initiated by the Spanish crown when this contract was broken and during the subsequent lengthy court cases (pleitos de Colón).

Columbus' theories

Christian Europe, which had long enjoyed safe passage to India and China‚ÄĒsources of valued goods such as silk and spices‚ÄĒunder the hegemony of the Mongol Empire (the Pax Mongolica, or "Mongol peace"), was by the fifteenth century, after the fragmentation of the Mongol Empire, under complete economic blockade by Muslim states. In response to Muslim domination on land, Portugal sought an eastward sea route to the Indies, and promoted the establishment of trading posts and later colonies along the African coast. Columbus had a different idea. By the 1480s, he had developed a plan to travel to the Indies (then construed roughly as all of south and east Asia) by instead sailing directly west across the "Ocean Sea" (the Atlantic).

It is sometimes claimed that the reason Columbus had difficulty obtaining support for his plan was that Europeans believed that the earth was flat.

Eratosthenes (276-194 B.C.E.) had already, in ancient Alexandrian times, accurately calculated the Earth's circumference. Most scholars accepted Ptolemy's claim that the terrestrial landmass (for Europeans of the time, comprising Eurasia and Africa) occupied 180 degrees of the terrestrial sphere, leaving 180 degrees of water.

Columbus, however, accepted the calculations of Marinus of Tyre that the landmass occupied 225 ¬į, leaving only 135 ¬į of water. Moreover, Columbus believed that 1 ¬į represented a shorter distance on the earth's surface than was commonly held. Finally, he read maps as if the distances were calculated in Italian miles (1238 meters or 4060 feet). Accepting the length of a degree to be 56 2/3 miles, from the writings of Alfraganus, he therefore calculated the circumference of the Earth as 25,255 km (15,700 modern statute miles) at most, and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan as 3000 Italian miles (some 3700 km). Columbus did not realize that Alfraganus used the much longer Arabic mile of about 1830 meters. He was not alone in "wishing" the earth smaller, however. A stunning image of the virtual Earth inside his mind survives to this day in a globe finished in 1492, by Martin Behaim of Nuremberg, Germany, "the Earthapple."

The problem facing Columbus was that most experts did not agree with his estimate of the distance to the Indies. The true circumference of the Earth is some 40,000 km (24,900 statute miles of 5280 feet each), and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan is some 10,600 nautical miles (19,600 km). No ship in the fifteenth century could carry enough food or sail fast enough from the Canary Islands to Japan.

Those experts were right, of course, but Spain, tenuously unified through the marriage of Ferdinand and Isabella, then suddenly unified in faith after an eight century struggle with the Muslims‚ÄĒfollowed by the expulsion of the Jews that same eventful year of 1492‚ÄĒwas in a messianic fever and desperate for a competitive edge over Portugal. The Portuguese had managed to circumnavigate Africa and were poised to establish trade with "the East Indies" (all of Asia). The Canaries, the Azores and the Madeira island groups had all been discovered within the past century. If nothing else, Columbus's scheme might turn up more islands, and in the unlikely event he was right about reaching "Farther India" in the western sea‚ÄĒand actually returned‚ÄĒit would have been a gamble worth taking.

Columbus was incorrect about the circumference of the Earth and the distance from the Canary Islands to Japan, but Europeans were mistaken in assuming that the aquatic expanse between Europe and Asia was uninterrupted by anything more than the mythical islands of medieval tradition. Columbus died believing he had opened up a direct nautical route to Asia. However, in his last year, Amerigo Vespucci (1454-1512) lived in his household and had confirmed from his own voyages that Columbus had found another continent (today's South America).

Voyages

Your Highnesses, as Catholic Christians, and princes who love and promote the holy Christian faith, and are enemies of the doctrine of Mahomet, and of all idolatry and heresy, determined to send me, Christopher Columbus, to the above-mentioned countries of India, to see the said princes, people, and territories, and to learn their disposition and the proper method of converting them to our holy faith; and furthermore directed that I should not proceed by land to the East, as is customary, but by a Westerly route, in which direction we have hitherto no certain evidence that anyone has gone (Christopher Columbus, journals on his voyage of 1492) (Markham, p. 16).

First voyage

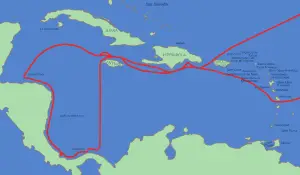

On the evening of August 3, 1492, Columbus left from Palos with three ships, the Santa Maria, Ni√Īa, and Pinta. The ships were property of Juan de la Cosa and the Pinz√≥n brothers (Martin and Vicente Y√°√Īez), but the monarchs forced the Palos inhabitants to contribute to the expedition. He first sailed to the Canary Islands, fortunately owned by Castile, where he re-provisioned and made repairs, and on September 6, started what turned out to be a five-week voyage across the ocean.

A legend is that the crew grew so homesick and fearful that they threatened to sail back to Spain. Although the actual situation is unclear, most likely the sailors' resentments merely amounted to complaints or suggestions.

After 29 days out of sight of land, on October 7, 1492, as recorded in the ship's log the crew spotted shore birds flying west and changed direction to make their landfall. A later comparison of dates and migratory patterns leads to the conclusion that the birds were Eskimo curlews and American golden plovers.

Land was sighted at 2 a.m. on October 12, by a sailor named Rodrigo de Triana (also known as Juan Rodriguez Bermejo) aboard Ni√Īa. Columbus called the island (in what is now The Bahamas) "San Salvador," although the natives called it Guanahani. The indigenous people he encountered, the Lucayan, Ta√≠no, or Arawak, were peaceful and friendly, and Columbus wished to bring them into the Christian fold or, on the Portuguese model, make them slaves to pay for the voyage. Slavery existed everywhere in the world, including the Americas, and Columbus would defend the Taino against the slave-raids of the Caribs. In general, however, his administrative abilities would prove to be poor. He was a merchant seafarer, not a conquistador or a crusader on the Spanish model.

He wrote of the Indians,

They … brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks' bells. They willingly traded everything they owned…. They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features…. They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane…. They would make fine servants…. With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want.

On this first voyage, Columbus also explored the northeast coast of Cuba (landed on October 28) and the northern coast of Hispaniola, by December 5. Here, the Santa Maria ran aground on Christmas morning 1492, and had to be abandoned. He was received by the native cacique Guacanagari, who gave him permission to leave some of his men behind. Columbus founded the settlement La Navidad and left 39 men.

On January 15, 1493, he set sail for home by way of the Azores. He wrestled his ship against the wind and ran into a fierce storm. Leaving the island of Santa Maria in the Azores, Columbus headed for Spain, but another storm forced him into Lisbon. He anchored next to the King's harbor patrol ship on March 4, 1493, where he was told a fleet of 100 caravels had been lost in the storm. Astoundingly, both the Ni√Īa and the Pinta were spared. Not finding the King in Lisbon, Columbus wrote a letter to him and waited for the king's reply, which requested that he go to Vale do Para√≠so to meet with His Majesty. Some have speculated that his landing in Portugal was intentional.

Relations between Portugal and Castile were poor at the time. Columbus went to meet with the king at Vale do Paraíso (north of Lisbon). After spending more than one week in Portugal, he set sail for Spain. Word of his finding new lands rapidly spread throughout Europe. He did not reach Spain until March 15.

He was received as a hero in Spain. This was his moment in the sun. He displayed several kidnapped natives and what gold he had found to the court, as well as the previously unknown tobacco plant, the pineapple fruit, the turkey, and the sailor's first love, the hammock. He did not bring any of the coveted East Indies spices, such as the exceedingly expensive black pepper, ginger, or cloves. In his log, he wrote "there is also plenty of ají, which is their pepper, which is more valuable than black pepper, and all the people eat nothing else, it being very wholesome" (Turner, 2004: 11). The word ají is still used in South American Spanish for chili peppers.

Second voyage

Admiral Columbus left from Cádiz, Spain, to find more places on September 24, 1493, with 17 ships carrying supplies, and about 1200 men to assist in the conquering of the Taíno and the colonization of the region. It was a strategic military move on behalf of Spain, which was seeking colonies. On October 13, the ships left the Canary Islands, following a more southerly course than on the first voyage.

On November 3, 1493, Columbus sighted a rugged island that he named Dominica. On the same day, he landed at Marie-Galante, which he named Santa Maria la Galante. After sailing past Les Saintes (Todos los Santos), he arrived at Guadaloupe (Santa Maria de Guadalupe), which he explored between November 4 and November 10, 1493. The exact course of his voyage through the Lesser Antilles is debated, but it seems likely that he turned north, sighting and naming several islands including Montserrat (Santa Maria de Monstserrate), Antigua (Santa Maria la Antigua), Redonda (Santa Maria la Redonda), Nevis (Santa María de las Nieves), Saint Kitts (San Jorge), Saint Eustatius (Santa Anastasia), Saba (San Cristobal), Saint Martin (San Martin), and Saint Croix (Santa Cruz). He also sighted the island chain of the Virgin Islands, which he named Santa Ursula y las Once Mil Virgines, and named the islands of Virgin Gorda, Tortola, and Peter Island (San Pedro).

He continued to the Greater Antilles, and landed at Puerto Rico (San Juan Bautista) on November 19, 1493. On November 22, he returned to Hispaniola, where he found his colonists had fallen into dispute with natives in the interior and had been killed. He established a new settlement at Isabella, on the north coast of Hispaniola where gold had first been found, but it was a poor location, and the settlement was also short-lived. He spent some time exploring the interior of the island for gold, and did find some, establishing a small fort in the interior. He left Hispaniola on April 24, 1494, and arrived at Cuba (which he named Juana) on April 30, and Jamaica on May 5. He explored the south coast of Cuba, which he believed to be a peninsula rather than an island, and several nearby islands, including the Isle of Youth (La Evangelista), before returning to Hispaniola on August 20.

Before he left Spain for his second voyage, he had been directed by Ferdinand and Isabella to maintain friendly, even loving relations with the natives. However, during his second voyage he sent a letter to the monarchs proposing to enslave some of the native peoples, specifically the Caribs, on the grounds of their aggressiveness. However, it seemed as if he had other intentions, as he previously had used Taino slaves for prostitution. Although his petition was refused by the Crown, in February 1495, Columbus took 1600 Arawak (a different tribe, who were hunted by the Carib) as slaves. He shipped 560 of them as slaves to Spain; 200 died en route, probably of disease, and of the remainder, half were ill when they arrived. After legal proceedings, the survivors were released and ordered to be shipped home. Others of the 1600 were kept as slaves for Columbus' men in the Americas, and Columbus recorded using slaves for sex in his journal. A remaining 400 captives, for whom Columbus had no use, were released. They fled into the hills, making, according to Columbus, prospects for their future capture dim. Rounding up the slaves led to the first major battle between the Spanish and the natives in the New World.

The main objective of Columbus' journey had been gold. To further this goal, he imposed a system on the natives in Cicao on Haiti, whereby all those above 14 years of age had to find a certain quota of gold, to be signified by a token placed around their necks. Those who failed to reach their quota would have their hands chopped off. Despite such extreme measures, Columbus did not manage to obtain much gold. One of the primary reasons for this was the fact that natives became infected with various diseases carried by the Europeans.

In his letters to the Spanish King and Queen, Columbus repeatedly suggested slavery as a way to profit from the new colonies, but these suggestions were rejected by the monarchs, who preferred to view the natives as future members of Christendom.

From Haiti, he returned to Spain.

Third voyage and arrest

On May 30, 1498, Columbus left with six ships from Sanl√ļcar de Barrameda, Spain, for his third trip to the New World. He was accompanied by the young Bartolom√© de Las Casas, who would later provide partial transcripts of Columbus' logs.

Columbus led the fleet to the Portuguese island of Porto Santo, where his wife, Felipa Perestrello e Moniz, was from. He then sailed to Madeira and spent some time there with the Portuguese captain João Gonçalves da Camara before sailing to the Canary Islands and Cape Verde. Columbus landed on the south coast of the island of Trinidad on July 31. From August 4 through August 12, he explored the Gulf of Paria which separates Trinidad from Venezuela. He explored the mainland of South America, including the Orinoco River. He also sailed to the islands of Chacachacare and Margarita Island and sighted and named Tobago (Bella Forma) and Grenada (Concepcion). He described the new lands as belonging to a previously unknown new continent, but pictured it hanging from China, bulging out to make the earth pear-shaped. (His inner map had run out of room.)

Columbus returned to Hispaniola on August 19, to find that many of the Spanish settlers of the new colony were discontent, having been misled by Columbus about the supposedly bountiful riches of the new world. Columbus repeatedly had to deal with rebellious settlers and natives. He had some of his crew hanged for disobeying him. A number of returned settlers and friars lobbied against Columbus at the Spanish court, accusing him of mismanagement. The king and queen sent the royal administrator Francisco de Bobadilla in 1500, who upon arrival on August 23, detained Columbus and his brothers and had them shipped home. Columbus refused to have his shackles removed on the trip to Spain, during which he wrote a long and pleading letter to the Spanish monarchs. They accepted his letter and let Columbus and his brothers go.

Although he regained his freedom, he did not regain his prestige and he lost his governorship. As an added insult, the Portuguese had won the race to the Indies: Vasco da Gama returned in September 1499, from a trip to India, having sailed east around Africa.

Fourth voyage

Nevertheless, Columbus made a fourth voyage, nominally in search of the Strait of Malacca to the Indian Ocean.

Accompanied by his brother Bartolomeo and his 13-year-old son, Fernando, he left C√°diz, Spain, on May 11, 1502. He sailed to Arzila on the Moroccan coast to rescue the Portuguese soldiers who he heard were under siege by the Moors. On June 15, they landed at Carbet on the island of Martinique (Martinica). A hurricane was brewing, so he continued on, hoping to find shelter on Hispaniola. He arrived at Santo Domingo on June 29, but was denied port, and the new governor refused to listen to his storm prediction. Instead, while Columbus's ships sheltered at the mouth of the Jaina River, the first Spanish treasure fleet sailed into the teeth of a hurricane.

The only ship to reach Spain had Columbus's money and belongings on it, and all of his former enemies (and a few friends) had drowned.

After a brief stop at Jamaica, He sailed to Central America, arriving at Guanaja (Isla de Pinos) in the Bay Islands off the coast of Honduras on July 30. Here, Bartolomeo found native merchants and a large canoe, which was described as "long as a galley" and was filled with cargo. On August 14, he landed on the American mainland at Puerto Castilla, near Trujillo, Honduras. He spent two months exploring the coasts of Honduras, Nicaragua, and Costa Rica, before arriving in Almirante Bay, Panama on October 16.

In Panama, he learned from the natives of gold and a strait to another ocean. After much exploration, he established a garrison at the mouth of Rio Belen in January 1503. On April 6, one of the ships became stranded in the river. At the same time, the garrison was attacked, and the other ships were damaged. He left for Hispaniola on April 16, but sustained more damage in a storm off the coast of Cuba. Unable to travel any farther, the ships were beached in St. Ann's Bay, Jamaica, on June 25, 1503.

Columbus and his men were stranded on Jamaica for a year. Two Spaniards, with native paddlers, were sent by canoe to get help from Hispaniola. In the meantime, in a desperate effort to induce the natives to continue provisioning him and his hungry men, he successfully intimidated the natives by correctly predicting a lunar eclipse, using astronomic tables made by Rabbi Avraham Zacuto, who was working for the King of Portugal. Grudging help finally arrived on June 29, 1504, and Columbus and his men arrived in Sanl√ļcar de Barrameda, Spain on November 7.

Later life

While Columbus had always given the conversion of non-believers as one reason for his explorations, he grew increasingly religious in his later years. He claimed to hear divine voices, lobbied for a new crusade to capture Jerusalem, often wore Franciscan habit, and described his explorations to the "paradise" as part of God's plan which would soon result in the Last Judgement and the end of the world.

In his later years, Columbus demanded that the Spanish Crown give him 10 percent of all profits made in the new lands, pursuant to earlier agreements. Because he had been relieved of his duties as governor, the crown did not feel bound by these contracts and his demands were rejected. His family later sued for part of the profits from trade with America, but ultimately lost some 50 years later.

On May 20, 1506, Columbus died in Valladolid, fairly wealthy due to the gold his men had accumulated in Hispaniola. He was still convinced that his journeys had been along the east coast of Asia. Following his death, his body underwent excarnation‚ÄĒthe flesh was removed so that only his bones remained. Even after his death, his travels continued: First interred in Valladolid and then at the monastery of La Cartuja in Seville, by the will of his son Diego, who had been governor of Hispaniola, his remains were transferred to Santo Domingo in 1542. In 1795, the French took over, and his remains was removed to Havana. After Cuba became independent following the Spanish-American War in 1898, his remains were moved back to the Cathedral of Seville, where they were placed on an elaborate catafalque. However, a lead box bearing an inscription identifying "Don Christopher Columbus" and containing fragments of bone and a bullet was discovered at Santo Domingo in 1877. To lay to rest claims that the wrong relics were moved to Havana and that Columbus is still buried in the cathedral of Santo Domingo, DNA samples were taken in June 2003 (History Today August 2003). Results announced in May 2006 show that at least some of Columbus' remains rest in Seville, but authorities in Santo Domingo have not allowed the remains in their custody to be tested.

Perceptions of Columbus

The casting of Columbus as a "hero" or "villain" often depends on people's perspectives as to whether the arrival of Europeans to the New World and the introduction of Christianity is seen as positive or negative. In addition, the Columbus voyage has been woven into the narrative of nations that established sovereignty in the Americas in later centuries, and the political perceptions relative to those governments, most prominently the United States as a global superpower.

Traditionally, Columbus is viewed as a man of heroic stature by some people in the United States. He has often been hailed as a man of heroism and bravery, and also of faith: He sailed westward into mostly unknown waters, and his unique scheme is often viewed as ingenious. Columbus wrote of his journey, "God gave me the faith, and afterwards the courage." He "set an example for us all by showing what monumental feats can be accomplished through perseverance and faith" (George H.W. Bush, June 8, 1989).

Hero worship of Columbus perhaps reached a zenith around 1892, the 400th anniversary of his first arrival in the Americas. Monuments to Columbus (including the Columbian Exposition in Chicago) were erected throughout the United States and Latin America, extolling him as a hero. Numerous cities, towns, and streets were named for him, including the capital cities of two U.S. states (Columbus, Ohio and Columbia, South Carolina). The Knights of Columbus, a Catholic men's fraternal benefit society, had been chartered ten years earlier by the State of Connecticut. The story that Columbus thought the world was round while his contemporaries believed in a Flat Earth was often repeated. This tale was used to show that Columbus was enlightened and forward looking. Columbus' apparent defiance of convention in sailing west to get to the far east was hailed as a model of "American"-style can-do inventiveness.

In the United States, the admiration of Columbus was particularly embraced by some members of the Italian American, Hispanic, and Catholic communities. These groups point to Columbus as one of their own to show that Mediterranean Catholics could and did make great contributions to the U.S. The modern vilification of Columbus is seen by his supporters as being politically motivated.

A contrary view of Columbus has gained ascendancy in recent decades with the rise of movements for indigenous rights. Criticism focuses on the continuing propaganda cultivated in Columbus myths and celebrations (such as Columbus Day) and their effects on American thought towards present-day Native Americans (New World Mongoloids). Official celebrations of the 500th anniversary of Columbus' first 1492 voyage were muted in some areas, and a few demonstrators protested marking the anniversary at all. It was in this spirit that Venezuelan President Hugo Chávez signed, in October, 2002, a decree changing the name of Venezuela's "Columbus Day" to "The Day of Indigenous Resistance" in honor of the nation's indigenous groups. On October 12, 2004, supporters of Chávez destroyed a 100-year old statue of Columbus in Caracas. They did this because they found Columbus and Spain guilty of "imperialist genocide." The genocide and atrocious acts committed by the Spanish against the natives (the Tainos in particular) are well documented in terrifying detail by Bartolomé de Las Casas in his letters and book A Short Account of the Destruction of the Indies. After Columbus' death in 1506, the genocide of many Indians made Bartolemé de Las Casas persuade the Spaniards to use African slaves instead. In the 1530s, the Spanish conquistadors brought many slaves to the New World from Africa. Bartolomé de Las Casas would later regret this as he saw the rough treatment of the African slaves by the Spaniards.

What has been called the Columbian Exchange (a term coined by Alfred W. Crosby) brought a cross-fertilization that yielded both benefits and great social costs. Most importantly for Native Americans, the introduction of epidemic diseases such as smallpox, measles, and syphilis decimated native populations. The Native Americans, in turn, introduced tobacco to Europeans. Columbus himself brought back tobacco from his first voyage, originally thought to have medicinal properties, but which over centuries of abuse has proven to be a dangerous and addictive plant when ingested. In addition, the Old World gained potatoes, turkeys, rubber, and tomatoes, while the New World gained domesticated livestock, numerous foodstuffs, and modern methods of agriculture and husbandry. The legacy of Columbus continues five centuries later, with the growing integration of world trade, cultural exchange, and the modern emergence of the Pacific Rim into a globalized economy.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cohen, John Michael. The Four Voyages of Christopher Columbus: Being His Own Log-Book, Letters and Dispatches With Connecting Narrative Drawn from the Life of the Admiral by His Son Hernando Colon and Others. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1969. ISBN 0140442170.

- Cook, Sherburne Friend, and Woodrow Wilson Borah. Essays in Population History Volume I. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1971. ISBN 0520017641.

- Crosby, Alfred W. The Columbian Voyages, the Columbian Exchange, and Their Historians. Washington, DC: American Historical Association, 1987. ISBN 0872290395.

- Crosby, Alfred W. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. New York: Praeger, 2003. ISBN 0275980928.

- Friedman, Thomas. The World Is Flat: A Brief History Of The Twenty-first Century. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006. ISBN 9780374292799.

- Hart, Michael H. The 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Persons in History . Secausus, N.J.: Carol Publishing Group, 1992. ISBN 0806513500.

- Keen, Benjamin (trans.). The Life of the Admiral Christopher Columbus by his Son Ferdinand,. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press 1978. ISBN 0313201757.

- Markham, Clements R. The Journal of Christopher Columbus (during His First Voyage, 1492-93) and Documents Relating to the Voyages of John Cabot and Gaspar Corte Real. (1893). Google Books. Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot. Admiral of the Ocean Sea: A Life of Christopher Columbus. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1983. ISBN 0930350375.

- Nelson, Diane M. A Finger in the Wound : Body Politics in Quincentennial Guatemala. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1999. ISBN 0520212851.

- Patrick, John J. Teaching about the Voyages of Columbus. ERIC Digest. ERIC Clearinghouse for Social Studies/Social Science Education Bloomington IN, 1992.

- Turner, Jack. Spice: The History of a Temptation. New York: Knopf, 2004. ISBN 0375407219.

- Urvoy, Jean-Michel. "O√Ļ est enterr√© Christophe Colomb¬†?" (Trans. Where is buried Christopher Columbus) Retrieved June 10, 2008.

- Wilford, John Noble, and Ashbel Green. The Mysterious History of Columbus: An Exploration of the Man, the Myth, the Legacy. New York: Vintage Books, 1992. ISBN 0679738320.

External links

All links retrieved December 10, 2023.

- A reconstructed portrait of Christopher Columbus, based on historical sources, in a contemporary style.

- Find-A-Grave profile of Christopher Columbus

- The Round Earth and Christopher Columbus"   (educational site, includes lesson plan)

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.