Microbiotheria

| Microbiotheres

| ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

†Khasia |

Microbiotheria is an order of New World marsupials of which the only living species is the Monito del monte or colocolo, a mouse-sized, tree climber species found in Chile and Argentina.

members of the order Didelphimorphia (the order that contains the Virginia opossum), an accumulation of both anatomical and genetic evidence in recent years has led to the conclusion that microbiotheres are not didelphids at all, but are instead most closely related to the Australasian marsupials; together, the microbiotheres and the Australian orders form the clade Australidelphia.

The monito del monte is the only extant member of its family (Microbiotheriidae) and the only surviving member of an ancient order, the Microbiotheria.[1] The oldest microbiothere currently recognised is Khasia cordillerensis, based on fossil teeth from Early Palaeocene deposits at Tiupampa, Bolivia. Numerous genera are known from various Palaeogene and Neogene fossil sites in South America. A number of possible microbiotheres, again represented by isolated teeth, have also been recovered from the Middle Eocene La Meseta Formation of Seymour Island, Western Antarctica. Finally, several undescribed microbiotheres have been reported from the Early Eocene Tingamarra Local Fauna in Northeastern Australia; if this is indeed the case, then these Australian fossils have important implications for understanding marsupial evolution and biogeography.

Although once thought to be members of the order Didelphimorphia (the order that contains the Virginia opossum), an accumulation of both anatomical and genetic evidence in recent years has led to the conclusion that microbiotheres are not didelphids at all, but are instead most closely related to the Australasian marsupials; together, the microbiotheres and the Australian orders form the clade Australidelphia. The distant ancestors of the monito del monte, it is thought, remained in what is now South America while others entered Antarctica and eventually Australia during the time when all three continents were joined as part of Gondwana.[2][3]

Monito del monte

| Monito del monte[1] | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Dromiciops gliroides Thomas, 1894 | ||||||||||||||||||

Map of Dromiciops gliroides distribution

| ||||||||||||||||||

|

Dromiciops australis |

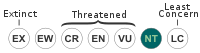

The monito del monte (Spanish for "little bush monkey"), Dromiciops gliroides, also called chumaihuén in Mapudungun, is a diminutive marsupial native only to southwestern South America (Chile and Argentina). It is the only extant species in the ancient order Microbiotheria, and the sole New World representative of the superorder Australidelphia (all other New World marsupials are members of Ameridelphia). The species is nocturnal and arboreal, and lives in thickets of South American mountain bamboo in the Valdivian temperate rain forests of the southern Andes,[4] aided by its partially prehensile tail.[5] It eats primarily insects and other small invertebrates, supplemented with fruit.[5]

Phylogeny and biogeography

It has long been suspected that South American marsupials were ancestral to those of Australia, consistent with the fact that the two continents were connected via Antarctica in the early Cenozoic. Australia’s earliest known marsupial is Djarthia, a primitive mouse-like animal that lived about 55 million years ago. Djarthia had been identified as the earliest known australidelphian, and this research suggested that the monito del monte was the last of a clade which included Djarthia.[6] This implied that the ancestors of the Monito del Monte might have reached South America via a back-migration from Australia. The time of divergence between the Monito del Monte and Australian marsupials was estimated to have been 46 million years ago.[5] However, in 2010, analysis of retrotransposon insertion sites in the nuclear DNA of a variety of marsupials, while confirming the placement of the Monito del Monte in Australidelphia, showed that its lineage is the most basal of that superorder. The study also confirmed that the most basal of all marsupial orders are the other two South American lineages (Didelphimorphia and Paucituberculata, with the former probably branching first). This indicates that Australidelphia arose in South America (along with the ancestors of all other living marsupials), and probably reached Australia in a single dispersal event after Microbiotheria split off.[2][7][3]

Size

Body length is 11–12.5 cm. Tail length is 9–10 cm.[citation needed]

Reproduction

The monito del monte normally reproduces in the spring and can have a litter size varying anywhere from one to four young. The females have a pseudovagina, and a fur-lined pouch containing four mammae. When the young are mature enough to leave the pouch they are nursed in a nest, and then carried on the mother’s back. The young remain in association with the mother after weaning. Males and females both reach sexual maturity after 2 years. They are known to reproduce aggressively, sometimes leaving blood on the reproductive organs. [1][8][9][10]

Habitat

Monitos del monte mainly live in trees, where they construct spherical nests of water resistant colihue leaves. These leaves are then lined with moss or grass, and placed in well protected areas of the tree. The nests are sometimes covered with grey moss as a form of camouflage. These nests provide the monito del monte with some protection from the cold, both when it is active and when it hibernates. It stores fat in the base of its tail for winter hibernation. It lives in the dense, humid forests of highland Chile and Argentina.[11][12][13]

Role as a seed disperser

A study performed in the temperate forests of southern Argentina showed a mutualistic seed dispersal relationship between D. gliroides and Tristerix corymbosus, also known as the Loranthacous mistletoe. The monito del monte is the single dispersal agent for this plant, and without it the plant would likely become extinct. The monito del monte eats the fruit of T. corymbosus, and thus disperses the seeds. Scientists speculate that the coevolution of these two species could have begun 60–70 million years ago.[14][15]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Template:MSW3 Microbiotheria Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "msw3" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 2.0 2.1 Schiewe, Jessie (2010-07-28). Australia's marsupials originated in what is now South America, study says. LATimes.Com. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2010-08-01.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Nilsson, M. A. and Churakov, G.;, Sommer, M.; Van Tran, N.; Zemann, A.; Brosius, J.; Schmitz, J. (2010-07-27). Tracking Marsupial Evolution Using Archaic Genomic Retroposon Insertions. PLoS Biology 8 (7): e1000436. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Nilsson" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 4.0 4.1 Diaz, M. & Teta, P. (2008). Dromiciops gliroides. In: IUCN 2008. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Downloaded on 28 December 2008. Database entry includes justification for why this species is listed as near threatened

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Monito del monte (Dromiciops gliroides). EDGE of Existence programme. Zoological Society of London (2006-08-09). Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- ↑ Beck, Robin M. D. and Godthelp, Henk; Weisbecker, Vera; Archer, Michael; Hand, Suzanne J. (2008-03-26). Australia's Oldest Marsupial Fossils and their Biogeographical Implications. PLoS ONE 3 (3): e1858.

- ↑ Inman, M. (2010-07-27). Jumping Genes Reveal Kangaroos' Origins. PLoS Biology 8 (7): e1000437.

- ↑ Spotorno, Angel E. and Marin, Juan C.; Yevenes, Marco; Walker, Laura I.; Donoso, Raul Fernandez; Pinchiera, Juana; Barrios, M. Soleda; Palma, R. Eduardo (December 1997). Chromosome Divergences Among American Marsupials and the Australian Affinities of the American Dromiciops. Journal of Mammalian Evolution 4 (4): 259–269.

- ↑ Brugni, Norma and Flores, Veronica R. (September 2007). Allassogonoporus dromiciops n. sp. (Digenea: Allassogonoporidae) from Dromiciops gliroides (Marsupialia: Microbiotheriidae) in Patagonia, Argentina. Systematic Parasitology 68 (1): 45–48.

- ↑ Lidicker, Jr., William Z., Michael T. Ghiselin (1996). Biology. Menlo Park, California: The Benjamin/Cummings Publishing Company.

- ↑ Macdonald, David (1995). Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York City: Facts on File.

- ↑ Nowak, Ronald M., Chris R. Dickman (2005). Walker's Marsupials of the World. JHU Press.

- ↑ Lord, Rexford D. (2007). Mammals of South America. JHU Press.

- ↑ Garcia, Daniel (March 2009). Seed dispersal by a frugivorous marsupial shapes the spatial scale of a mistletoe population. Journal of Ecology 97 (2): 217–229.

- ↑ Amico, Guillermo C. and Rodriguez-Cabal, Mariano A.; Aizen, Marcelo A. (January–February 2009). The potential key seed-dispersing role of the arboreal marsupial Dromiciops gliroides. Acta Oecologica 35 (1): 8–13.

Siciliano Martina, L. 2014. "Microbiotheria" (On-line), Animal Diversity Web. Accessed May 12, 2014 at http://animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu/accounts/Microbiotheria/

| Mammals |

|---|

| Monotremata (platypus, echidnas) |

|

Marsupialia: | Paucituberculata (shrew opossums) | Didelphimorphia (opossums) | Microbiotheria | Notoryctemorphia (marsupial moles) | Dasyuromorphia (quolls and dunnarts) | Peramelemorphia (bilbies, bandicoots) | Diprotodontia (kangaroos and relatives) |

|

Placentalia: Cingulata (armadillos) | Pilosa (anteaters, sloths) | Afrosoricida (tenrecs, golden moles) | Macroscelidea (elephant shrews) | Tubulidentata (aardvark) | Hyracoidea (hyraxes) | Proboscidea (elephants) | Sirenia (dugongs, manatees) | Soricomorpha (shrews, moles) | Erinaceomorpha (hedgehogs and relatives) Chiroptera (bats) | Pholidota (pangolins)| Carnivora | Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates) | Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates) | Cetacea (whales, dolphins) | Rodentia (rodents) | Lagomorpha (rabbits and relatives) | Scandentia (treeshrews) | Dermoptera (colugos) | Primates | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.