Surrealism

| Surrealism |

|

Surrealism main article |

Surrealism[1] is a cultural movement that began in the mid-1920s, and is best known for the visual artworks and writings of the group members. From the Dada activities of World War I Surrealism was formed with the most important center of the movement in Paris and from the 1920s spreading around the globe.

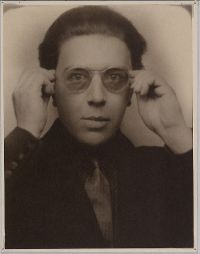

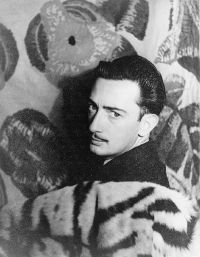

The works feature the element of surprise, unexpected juxtapositions and the use of non sequiturs. Many Surrealist artists and writers regard their work as an expression of the philosophical movement first and foremost with the works serving merely as an artefact. Their leader, Frenchman André Breton, was explicit in his assertion that Surrealism was above all a revolutionary movement. Breton was an ardent communist, and numerous important Surrealist artists, including perhaps its most famous practicioner, Salvador Dali, would break from Breton over his political commitments.

Founding of the movement

World War I scattered the writers and artists who had been based in Paris, and while away from Paris many involved themselves in the Dada movement believing that excessive rational thought and bourgeois values had brought the terrifying conflict upon the world. The Dadaists protested with anti-rational anti-art gatherings, performances, writing and art works. After the war when they returned to Paris the Dada activities continued.

During the war Surrealism's soon-to-be leader André Breton, who had trained in medicine and psychiatry, served in a neurological hospital where he used the psychoanalytic methods of Sigmund Freud with soldiers who were shell-shocked. He also met the young writer Jacques Vaché and felt that he was the spiritual son of writer and pataphysician Alfred Jarry. He came to admire the young writer's anti-social attitude and disdain for established artistic tradition. Later Breton wrote, "In literature, I am successively taken with Rimbaud, with Jarry, with Apollinaire, with Nouveau, with Lautréamont, but it is Jacques Vaché to whom I owe the most."

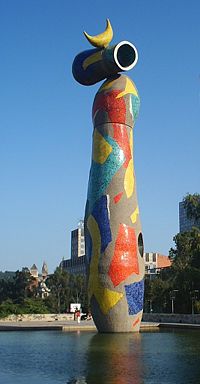

Back in Paris Breton joined in the Dada activities and also started the literary journal LittĂ©rature along with Louis Aragon and Philippe Soupault. They began experimenting with automatic writingâspontaneously writing without censoring their thoughts, and published the "automatic" writings, as well as accounts of dreams, in LittĂ©rature. Breton and Soupault delved deeper into automatism, writing the novel Les Champs MagnĂ©tiques (The Magnetic Fields) in 1920 using this technique. They continued the automatic writing, gathering more artists and writers into the group, and coming to believe that automatism was a better tactic for societal change than the Dada attack on prevailing values. In addition to Breton, Aragon and Soupault the original Surrealists included Paul Ăluard, Benjamin PĂ©ret, RenĂ© Crevel, Robert Desnos, Jacques Baron, Max Morise, Marcel Noll, Pierre Naville, Roger Vitrac, Simone Breton, Gala Ăluard, Max Ernst, Man Ray, Hans Arp, Georges Malkine, Michel Leiris, Georges Limbour, Antonin Artaud, Raymond Queneau, AndrĂ© Masson, Joan MirĂł, Marcel Duhamel, Jacques PrĂ©vert and Yves Tanguy.[2]

While Dada rejected categories and labels, Surrealism would advocate the idea that while ordinary and depictive expressions are vital and important, their arrangement must be open to the full range of imagination according to the Hegelian Dialectic. They also looked to the Marxist dialectic and the work of such theorists as Walter Benjamin and Herbert Marcuse.

Freud's work with free association, dream analysis and the hidden unconscious was of the utmost importance to the Surrealists in developing methods to liberate the imagination. However, they embraced idiosyncrasy, while rejecting the idea of an underlying madness or darkness of the mind.

The group aimed to revolutionize human experience, including its personal, cultural, social, and political aspects, by freeing people from what they saw as false rationality, and restrictive customs and structures. Breton proclaimed, the true aim of Surrealism is "long live the social revolution, and it alone!" To this goal, at various times surrealists aligned with communism and anarchism.

In 1924 they declared their intents and philosophy with the issuance of the first Surrealist Manifesto. That same year they established the Bureau of Surrealist Research, and began publishing the journal La Révolution surréaliste.

Surrealist Manifesto

Breton wrote the manifesto of 1924 (another was issued in 1929) that defines the purposes of the group and includes citations of the influences on Surrealism, examples of Surrealist works and discussion of Surrealist automatism. He defined Surrealism as:

Dictionary: Surrealism, n. Pure psychic automatism, by which one proposes to express, either verbally, in writing, or by any other manner, the real functioning of thought. Dictation of thought in the absence of all control exercised by reason, outside of all aesthetic and moral preoccupation.

Encyclopedia: Surrealism. Philosophy. Surrealism is based on the belief in the superior reality of certain forms of previously neglected associations, in the omnipotence of dream, in the disinterested play of thought. It tends to ruin once and for all other psychic mechanisms and to substitute itself for them in solving all the principal problems of life. Andre Breton

Manifesto of 1924

Breton would later qualify the first of these definitions by saying "in the absence of conscious moral or aesthetic self-censorship," and by his admission through subsequent developments, that these definitions were capable of considerable expansion.

La Révolution surréaliste

Shortly after releasing the first Surrealist Manifesto in 1924, the Surrealists published the inaugural issue of La Révolution surréaliste and publication continued into 1929. Pierre Naville and Benjamin Péret were the initial directors of the publication, modeling the format of the journal on the conservative scientific review La Nature. The format was deceiving, and to the Surrealists' delight La Révolution surréaliste was consistently scandalous and revolutionary. The journal focused on writing with most pages densely packed with columns of text, but also included reproductions of art, among them works by Giorgio de Chirico, Max Ernst, André Masson and Man Ray.

Bureau of Surrealist Research

The Bureau of Surrealist Research (Centrale Surréaliste) was the Paris office where the Surrealist writers and artists gathered to meet, hold discussions, and conduct interviews with the goal of investigating speech under trance.

Expansion

The movement in the mid-1920s was characterized by meetings in cafes where the Surrealists played collaborative drawing games and discussed the theories of Surrealism. The Surrealists developed techniques such as automatic drawing. (See Surrealist techniques and games.)

Breton initially doubted that visual arts could even be useful in the Surrealist movement since they appeared to be less malleable and open to chance and automatism. This caution was overcome by the discovery of such techniques as "frottage" and "decalomania."

Soon more visual artists joined Surrealism including Giorgio de Chirico, Salvador DalĂ, Enrico Donati, Alberto Giacometti, Valentine Hugo, MĂ©ret Oppenheim, Toyen, GrĂ©goire Michonze, and Luis Buñuel. Though Breton admired Pablo Picasso and Marcel Duchamp and courted them to join the movement, they remained peripheral.[3]

More writers also joined, including former Dada leader Tristan Tzara, René Char, Georges Sadoul, André Thirion and Maurice Heine.

In 1925 an autonomous Surrealist group formed in Brussels, becoming official in 1926. The group included the musician, poet and artist E.L.T. Mesens, painter and writer RenĂ© Magritte, Paul NougĂ©, Marcel Lecomte, Camille Goemans, and AndrĂ© Souris. In 1927 they were joined by the writer Louis Scutenaire. They corresponded regularly with the Paris group, and in 1927 both Goemans and Magritte moved to Paris, frequenting Bretonâs circle.[2]

The artists, with their roots in Dada and Cubism, the abstraction of Wassily Kandinsky and Expressionism, and Post-Impressionism, also reached to older "bloodlines" such as Hieronymus Bosch, and the so-called primitive and naive arts.

André Masson's automatic drawings of 1923 are often viewed as the point of the acceptance of visual arts and the break from Dada, since they reflect the influence of the idea of the unconscious mind. Another example is Alberto Giacometti's 1925 Torso, which marked his movement to simplified forms and inspiration from pre-classical sculpture.

However, a striking example of the line used to divide Dada and Surrealism among art experts is the pairing of 1925's Little Machine Constructed by Minimax Dadamax in Person (Von minimax dadamax selbst konstruiertes maschinchen) with The Kiss (Le Baiser) from 1927 by Ernst. The former is generally held to have a distance, and erotic subtext, while the latter presents an erotic act openly and directly. In the latter the influence of MirĂł and the drawing style of Picasso is visible with the use of fluid curving and intersecting lines and color, while the former exhibits a directness that would later be influential in movements such as Pop art.

Giorgio de Chirico's development of Metaphysical art was one of the important connecting figures between the philosophical and visual aspects of Surrealism. Between 1911 and 1917, he adopted an unornamented depictional style whose surface would be adopted by others later. The Red Tower (La tour rouge) from 1913 shows the stark color contrasts and illustrative style later adopted by Surrealist painters. His 1914 The Nostalgia of the Poet (La Nostalgie du poete) has the figure turned away from the viewer, and the juxtaposition of a bust with glasses and a fish as a relief defies conventional explanation. He was also a writer, and his novel Hebdomeros presents a series of dreamscapes with an unusual use of punctuation, syntax and grammar designed to create a particular atmosphere and frame around its images. His images, including set designs for the Ballets Russes, would create a decorative form of visual Surrealism, and he would be an influence on the two artists who would be even more closely associated with Surrealism in the public mind: Salvador DalĂ and Magritte. He would, however, leave the Surrealist group in 1928.

In 1924, Miro and Masson applied Surrealism theory to painting explicitly leading to the La Peinture Surrealiste exhibition.

Breton published Surrealism and Painting in 1928 which summarized the movement to that point, though he continued to update the work until the 1960s.

Major exhibitions in the 1920s

- 1925 - La Peinture Surrealiste - The first ever Surrealist exhibition at Gallerie Pierre in Paris. Displayed works by Masson, Man Ray, Klee, MirĂł, and others. The show confirmed that Surrealism had a component in the visual arts (though it had been initially debated whether this was possible), techniques from Dada, such as photomontage were used.

- Galerie Surréaliste opened on March 26, 1926 with an exhibition by Man Ray.

Writing continues

The first Surrealist work, according to leader Breton, was Magnetic Fields (Les Champs Magnétiques) (1921). But even before that, in 1919, Littérature contained automatist works and accounts of dreams. The magazine and the portfolio both showed their disdain for literal meanings given to objects and focused rather on the undertones, the poetic undercurrents present. Not only did they give emphasis to the poetic undercurrents, but also to the connotations and the overtones which "exist in ambiguous relationships to the visual images."

Because Surrealist writers seldom, if ever, appear to organize their thoughts and the images they present, some people find much of their work difficult to parse. This notion however is a superficial comprehension, prompted no doubt by Breton's initial emphasis on automatic writing as the main route toward a higher reality. Butâas in Breton's case itselfâmuch of what is presented as purely automatic is actually edited and very "thought out." Breton himself later admitted that automatic writing's centrality had been overstated, and other elements were introduced, especially as the growing involvement of visual artists in the movement forced the issue, since automatic painting required a rather more strenuous set of approaches. Thus such elements as collage were introduced, arising partly from an ideal of startling juxtapositions as revealed in Pierre Reverdy's poetry. Andâas in Magritte's case (where there is no obvious recourse to either automatic techniques or collage) the very notion of convulsive joining became a tool for revelation in and of itself. Surrealism was meant to be always in fluxâto be more modern than modernâand so it was natural there should be a rapid shuffling of the philosophy as new challenges arose.

Surrealists revived interest in Isidore Ducasse, known by his pseudonym "Le Comte de Lautréamont" and for the line "beautiful as the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella," and Arthur Rimbaud, two late nineteenth century writers believed to be the precursors of Surrealism.

Examples of Surrealist literature are Crevel's Mr. Knife Miss Fork (1931), Aragon's Irene's Cunt (1927), Breton's Sur la route de San Romano (1948), Peret's Death to the Pigs (1929), and Artaud's Le Pese-Nerfs (1926).

La Révolution surréaliste continued publication into 1929 with most pages densely packed with columns of text, but also included reproductions of art, among them works by de Chirico, Ernst, Masson and Man Ray. Other works included books, poems, pamphlets, automatic texts and theoretical tracts.

Surrealism and Politics

Surrealism as a political force developed unevenly around the world, in some places more emphasis was on artistic practices, in other places political and in other places still, Surrealist praxis looked to supersize both the arts and politics.

Politically Surrealism was ultra-leftist, communist, or anarchist. The split from Dada has been characterized as a split between anarchists and communists, with the Surrealists as communist. Breton and his comrades supported Leon Trotsky and his International Left Opposition for a while, though there was a certain openness to anarchism that manifested more fully after World War II. Some Surrealists such as Benjamin Peret aligned with forms of left communism. DalĂ supported capitalism and the fascist dictatorship of Francisco Franco but cannot be said to represent a trend in Surrealism in this respect; in fact he was considered, by Breton and his associates, to have betrayed and left Surrealism.

Bretonâs followers, along with the Communist Party, believed they were working for the "liberation of man." However, Bretonâs group refused to prioritize the proletarian struggle over radical creation, consequently their struggles with the Party made the late 1920s a turbulent time for both. Many individuals closely associated with Breton, notably Louis Aragon, left his group to work more closely with the Communists.

In the "Declaration of January 27, 1925" members of the Paris-based Bureau of Surrealist Research (including André Breton, Louis Aragon, and, Antonin Artaud, as well as some two dozen others) declared their affinity for revolutionary politics.[4] While this was initially a somewhat vague formulation, by the 1930s many Surrealists had strongly identified themselves with communism. The foremost document of this tendency within Surrealism is the "Manifesto for a Free Revolutionary Art" published under the names of Breton and Diego Rivera but actually co-authored by Breton and Leon Trotsky.[5]

However, in 1933 the Surrealistsâ assertion that a 'proletarian literature' within a capitalist society was impossible led to their break with the Association des Ecrivains et Artistes RĂ©volutionnaires, and the expulsion of Breton, Ăluard and Crevel from the Communist Party.[2]

In 1925, the Paris Surrealist group and the extreme left of the French Communist Party came together to support Abd-el-Krim, leader of the Rif uprising against French colonialism in Morocco. In an open letter to writer and French ambassador to Japan, Paul Claudel, the Paris group announced:

"We Surrealists pronounced ourselves in favour of changing the imperialist war, in its chronic and colonial form, into a civil war. Thus we placed our energies at the disposal of the revolution, of the proletariat and its struggles, and defined our attitude towards the colonial problem, and hence towards the colour question."

Surrealist political engagement did not necessarily lead to a unified front. In 1929 the satellite group around the journal Le Grand Jeu, including Roger Gilbert-Lecomte, Maurice Henry and the Czech painter Josef Sima, was ostracized. Also in February, Breton asked Surrealists to assess their "degree of moral competence," and theoretical refinements included in the second manifeste du surréalisme excluded anyone reluctant to commit to collective action, including Leiris, Limbour, Morise, Baron, Queneau, Prévert, Desnos, Masson and Boiffard. They moved to the periodical Documents, edited by Georges Bataille, whose anti-idealist materialism produced a hybrid Surrealism exposing the base instincts of humans.[2]

Other members were ousted over the years for a variety of infractions, both political and personal, and others left of to pursue creativity of their own style.

Black Surrealism

The anticolonial revolutionary and proletarian politics of "Murderous Humanitarianism" (1932) which was drafted mainly by Rene Crevel, signed by AndrĂ© Breton, Paul Ăluard, Benjamin Peret, Yves Tanguy, and the Martiniquan Surrealists Pierre Yoyotte and J.M. Monnerot perhaps makes it the original document of what is later called 'black Surrealism',[6] although it is the contact between AimĂ© CĂ©saire and Breton in the 1940s in Martinique that really lead to the communication of what is known as 'black Surrealism'.

Anticolonial revolutionary writers in the Négritude movement of Martinique, a French colony at the time, took up Surrealism as a revolutionary method to critique European culture. This linked with other Surrealists and was very important for the subsequent development of Surrealism as a revolutionary praxis. The journal Tropiques, featuring the work of Cesaire along with René Ménil, Lucie Thésée, Aristide Maugée and others, was first published in 1940.[7]

Golden Age

Throughout the 1930s, Surrealism continued to become more visible to the public at large. A Surrealist group developed in Britain and, according to Breton, their 1936 London International Surrealist Exhibition was a high water mark of the period and became the model for international exhibitions.

DalĂ and Magritte created the most widely recognized images of the movement. DalĂ joined the group in 1929, and participated in the rapid establishment of the visual style between 1930 and 1935.

Surrealism as a visual movement had found a method: to expose psychological truth by stripping ordinary objects of their normal significance, in order to create a compelling image that was beyond ordinary formal organization, in order to evoke empathy from the viewer.

1931 marked a year when several Surrealist painters produced works which marked turning points in their stylistic evolution: Magritte's Voice of Space (La Voix des airs) is an example of this process, where three large spheres representing bells hang above a landscape. Another Surrealist landscape from this same year is Yves Tanguy's Promontory Palace (Palais promontoire), with its molten forms and liquid shapes. Liquid shapes became the trademark of DalĂ, particularly in his The Persistence of Memory, which features the image of watches that sag as if they are melting.

The characteristics of this styleâa combination of the depictive, the abstract, and the psychologicalâcame to stand for the alienation which many people felt in the modern period, combined with the sense of reaching more deeply into the psyche, to be "made whole with one's individuality."

Long after personal, political and professional tensions fragmented the Surrealist group, Magritte and DalĂ continued to define a visual program in the arts. This program reached beyond painting, to encompass photography as well, as can be seen from a Man Ray self portrait, whose use of assemblage influenced Robert Rauschenberg's collage boxes.

During the 1930s Peggy Guggenheim, an important American art collector, married Max Ernst and began promoting work by other Surrealists such as Tanguy and the British artist John Tunnard. However, by the Second World War, the taste of the American avant-garde swung decisively towards Abstract Expressionism with the support of key taste makers, including Guggenheim, Leo Steinberg and Clement Greenberg. However, Abstract Expressionism itself grew directly out of the meeting of American (particularly New York) artists with European Surrealists self-exiled during World War II. In particular, Arshile Gorky influenced the development of this American art form, which, as Surrealism did, celebrated the instantaneous human act as the well-spring of creativity. The early work of many Abstract Expressionists reveals a tight bond between the more superficial aspects of both movements, and the emergence (at a later date) of aspects of Dadaistic humor in such artists as Rauschenberg sheds an even starker light upon the connection. Up until the emergence of Pop Art, Surrealism can be seen to have been the single most important influence on the sudden growth in American arts, and even in Pop, some of the humor manifested in Surrealism can be found, often turned into cultural criticism.

Major exhibitions in the 1930s

- 1936 - London International Surrealist Exhibition was organized in London by the art historian Herbert Read, with an introduction by André Breton.

- 1936 - Museum of Modern Art in New York shows the exhibition Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism.

- 1938 - A new International Surrealist Exhibition was held at the Beaux-arts Gallery, Paris, with more than 60 artists from different countries, and showed around 300 paintings, objects, collages, photographs and installations. The Surrealists wanted to create an exhibition which in itself would be a creative act and called on Marcel Duchamp to do so. At the exhibition's entrance he placed Salvador DalĂ's Rainy Taxi (an old taxi rigged to produce a steady drizzle of water down the inside of the windows, and a shark-headed creature in the driver's seat and a blond mannequin crawling with live snails in the back) greeted the patrons who were in full evening dress. Surrealist Street filled one side of the lobby with mannequins dressed by various Surrealists. He designed the main hall to seem like subterranean cave with 1,200 coal bags suspended from the ceiling over a coal brazier with a single light bulb which provided the only lighting,[8] so patrons were given flashlights with which to view the art. The floor was carpeted with dead leaves, ferns and grasses and the aroma of roasting coffee filled the air. Much to the Surrealists' satisfaction the exhibition scandalized the viewers.[3]

World War II, the 1950s and 1960s

The Second World War overshadowed, for a time, almost all intellectual and artistic production. In 1941, Breton went to the United States, where he co-founded the short-lived magazine VVV with Max Ernst, Marcel Duchamp, and the American artist David Hare. However, it was the American poet, Charles Henri Ford, and his magazine View which offered Breton a channel for promoting Surrealism in the United States. The View special issue on Duchamp was crucial for the public understanding of Surrealism in America. It stressed his connections to Surrealist methods, offered interpretations of his work by Breton, as well as Breton's view that Duchamp represented the bridge between between the early modern movements such as Futurism and Cubism, and Surrealism.

Though the war proved disruptive for Surrealism, the works continued. Many Surrealist artists continued to explore their vocabularies, including Magritte. Many members of the Surrealist movement continued to correspond and meet. While DalĂ may have been excommunicated by Breton, he neither abandoned his themes from the 1930s, including references to the "persistence of time" in a later painting, nor did he become a depictive pompier. His classic period did not represent so sharp a break with the past as some descriptions of his work might portray, and some, such as Thirion, argued that there were works of his after this period that continued to have some relevance for the movement.

During the 1940s Surrealism's influence was also felt in England and America. Mark Rothko took an interest in biomorphic figures, and in England Henry Moore, Lucian Freud, Francis Bacon and Paul Nash used or experimented with Surrealist techniques. However, Conroy Maddox, one of the first British Surrealists whose work in this genre dated from 1935, remained within the movement, and organized an exhibition of current Surrealist work in 1978 in response to an earlier show which infuriated him because it did not properly represent Surrealism. Maddox's exhibition, titled Surrealism Unlimited, was held in Paris and attracted international attention. He held his last one-man show in 2002 before he died three years later.

Magritte's work became more realistic in its depiction of actual objects, while maintaining the element of juxtaposition, such as in Personal Values (Les Valeurs Personneles) (1951) and Empire of Light (LâEmpire des lumiĂšres) (1954). Magritte continued to produce works which have entered artistic vocabulary, such as Castle in the Pyrenees (La Chateau des Pyrenees) which refers back to Voix from 1931, in its suspension over a landscape.

Other figures from the Surrealist movement were expelled. Several of these artists, like Roberto Matta (by his own description) "remained close to Surrealism."[3]

Many new artists explicitly took up the Surrealist banner for themselves. Dorothea Tanning and Louise Bourgeois continued to work, for example, with Tanning's Rainy Day Canape from 1970. Duchamp continued to produce sculpture in secret including an installation with the realistic depiction of a woman viewable only through a peephole.

Breton continued to write and espouse the importance of liberating of the human mind, as with the publication The Tower of Light in 1952. Breton's return to France after the War, began a new phase of Surrealist activity in Paris, and his critiques of rationalism and dualism found a new audience. Breton insisted that that Surrealism was an ongoing revolt against the reduction of humanity to market relationships, religious gestures and misery and to espouse the importance of liberating of the human mind.

Major exhibitions of the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s

- 1942 - First Papers of Surrealism - New York - The Surrealists again called on Duchamp to design an exhibition. This time he wove a 3-dimensional web of string thoughout the rooms of the space, in some cases making it almost impossible to see the works.[9] He made a secret arrangement with an associate's son to bring his friends to the opening of the show, so that when the finely dressed patrons arrived they found a dozen children in athletic clothes kicking and passing balls, and skipping rope. His design for the show's catalog included "found," rather than posed, photographs of the artists.[3]

- 1947 - International Surrealist Exhibition - Paris

- 1959 - International Surrealist Exhibition - Paris

- 1960 - Surrealist Intrusion in the Enchanters' Domain - New York

Situationist International

Situationist International was formed in 1957 with the fusion of several extremely small artistic tendencies: Lettrist International, the International movement for an imaginist Bauhaus (an off-shoot of the avant-garde movement, COBRA), and the London Psychogeographical Association. The groups came together intending to reawaken the radical political potential of Surrealism.

In the 1960s, while the Situationist leader, Guy Debord, was critical and distanced himself from Surrealism, while others such as Asger Jorn were explicitly using Surrealist techniques and methods. The 1968 General strike and student revolt in France which was influenced by the Paris based Situationist International included a number of Surrealist ideas, and among the slogans the students spray-painted on the walls of the Sorbonne were familiar Surrealist ones. Joan MirĂł would commemorate this in a painting titled May 1968.

The End of Surrealism?

There is no clear consensus about the end of Surrealism, or even if there was an end to the Surrealist movement. Some art historians suggest that World War II effectively disbanded the movement. However, art historian Sarane Alexandrian (1970) states, "the death of AndrĂ© Breton in 1966 marked the end of Surrealism as an organized movement." There have also been attempts to tie the obituary of the movement to the 1989 death of Salvador DalĂ.

In Europe and all over the world since the 1960s, artists have combined Surrealism with a classical 16th century technique called mischtechnik rediscovered by Ernst Fuchs, a contemporary of DalĂ, and now practiced and taught by many followers, including the highly regarded Robert Venosa and Chris Mars who has recently exhibited at major museums. The former curator of the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, Michael Bell, has called this style of Surrealism "veristic Surrealism." Veristic Surrealism depicts with meticulous clarity and in great detail a world analogous to the dream world.

During the 1980s, behind the Iron Curtain, Surrealism again entered into politics with an underground artistic opposition movement known as the Orange Alternative. The Orange Alternative was created in 1981 by Waldemar Fydrych (alias 'Major'), a graduate of history and art history at the University of WrocĆaw. They used Surrealist symbolism and terminology in their large scale happenings organized in the major Polish cities during the Jaruzelski regime, and painted Surrealist graffiti on spots covering up anti-regime slogans. Major himself was the author of a "Manifesto of Socialist Surrealism." In this manifesto, he stated that the socialist (communist) system had become so Surrealistic that it could be seen as an expression of art itself.

Also, spin-offs of Surrealism abound such as the Situationists, the Revolutionary Surrealist Group, contemporary trends such as Massurrealism. Most are artists, writers and thinkers working in a style thought to be represented by or derived from ideas or styles of the so-called "Golden Age of Breton," although many claim to have new ideas.

One of the largest and most dynamic contemporary art movements is the combining of Surrealist and visionary artists. According to Terrance Lindall, in Art and Antiques Magazine March 2006, the movement incorporates many variations including Surreal/conceptual, Visionary, Fantastic, Symbolism, Magic Realism, the Vienna School, Neuve Invention, Outsider, the Macabre, Grotesque, and Singulier Art. Lindall produced a New International Surrealist Manifesto and created the show Brave Destiny at the Williamsburg Art & Historical Center in 2003, expressing this broad notion of Surrealism as an artistic style. The show, the largest Surrealist show ever held, incorporated nearly 500 artists from every continent and opened with a "Grand Surrealist Costume Ball," in the tradition of Surrealist balls put on by the Baroness de Rothschild until the death of DalĂ.

Surrealistic art remains enormously popular with museum patrons. The Guggenheim Museum in New York City held an exhibit, Two Private Eyes, in 1999, and in 2001 Tate Modern held an exhibition of Surrealist art that attracted over 170,000 visitors. In 2002 the Metropolitan Museum in New York City had a blockbuster show, Desire Unbound, and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris had a show called La Révolution surréaliste.

Impact of Surrealism

While Surrealism is typically associated with the arts, it has been said to transcend them; Surrealism has had an impact in many other fields. In this sense, Surrealism does not specifically refer only to self-identified "Surrealists," or those sanctioned by Breton; rather, it defines a range of creative acts of revolt and efforts to liberate the imagination.

In addition to Surrealist notions that are grounded in the ideas of Hegel, Marx and Freud, Surrealism is seen by its advocates as inherently dynamic and as dialectical in its mode of thought. Surrealists have also drawn on sources as seemingly diverse as Clark Ashton Smith, Montague Summers, Horace Walpole, Fantomas, The Residents, Bugs Bunny, comic strips, the obscure poet Samuel Greenberg and the hobo writer and humorist T-Bone Slim. As the effort of humanity to liberate imagination as an act of insurrection against society, Surrealism finds precedents in the alchemists, Hieronymus Bosch, Marquis de Sade, Charles Fourier, Comte de Lautreamont, Arthur Rimbaudand possibly even Dante, among many others.

Surrealists believe that non-Western cultures also provide a continued source of inspiration for Surrealist activity because some may strike up a better balance between instrumental reason and imagination in flight than does Western culture. Surrealism has had an identifiable impact on radical and revolutionary politics, both directlyâas some Surrealists joined or allied themselves with radical political groups, movements and partiesâas well as indirectly through it philosophical orientation. which emphasizes the intimate link between freeing the imagination and the liberation from repressive and archaic social structures. This was especially visible in the New Left of the 1960s and 1970s and the French revolt of May 1968, whose slogan "All power to the imagination" rose directly from French Surrealist thought and practice.

Many significant literary movements in the later half of the twentieth century were directly or indirectly influenced by Surrealism. Many themes and techniques commonly identified with Postmodernism are nearly identical to Surrealism. Perhaps the writers within the Postmodern era who have the most in common with Surrealism are the playwrights of Theater of the Absurd. Though not an organized movement, these playwrights were grouped together based on some similarities of theme and technique; these similarities can perhaps be traced to influence from the Surrealists. Eugene Ionesco in particular was fond of Surrealism, claiming at one point that Breton was one of the most important thinkers in history. Samuel Beckett was also fond of Surrealists, even translating much of the poetry into English; he may have had closer ties had the Surrealists not be critical of Beckett's mentor and friend, James Joyce. Many writers from and associated with the Beat Generation were influenced greatly by Surrealists. Philip Lamantia and Ted Joans are often categorized as both Beat and Surrealist writers. Many other Beat writers claimed Surrealism as a significant influence. A few examples include Bob Kaufman, Gregory Corso, and Allen Ginsberg. Magic Realism, a popular technique among novelists of the latter half of the 20th century especially among Latin American writers, has some obvious similarities to Surrealism with its juxtaposition of the normal and the dream-like. The prominence of Magic Realism in Latin American literature is often credited in some part to the direct influence of Surrealism on Latin American artists like Frida Kahlo.

Criticism of Surrealism

Feminist

Feminists have in the past critiqued the Surrealist movement, claiming that it is fundamentally a male movement and a male fellowship, despite the occasional few celebrated woman Surrealist painters and poets. They believe that it adopts typical male attitudes toward women, such as worshipping them symbolically through stereotypes and sexist norms. Women are often made to represent higher values and transformed into objects of desire and of mystery.[10]

One of the pioneers in feminist critique of Surrealism was XaviÚre Gauthier. Her book Surréalisme et Sexualité [11](1971) inspired further important scholarship related to the marginalization of women in relation to "the avant-garde."

Freudian

Freud initiated the psychoanalytic critique of Surrealism with his remark that what interested him most about the Surrealists was not their unconscious but their conscious. His meaning was that the manifestations of and experiments with psychic automatism highlighted by Surrealists as the liberation of the unconscious were highly structured by ego activity, similar to the activities of the dream censorship in dreams, and that therefore it was in principle a mistake to regard Surrealist poems and other art works as direct manifestations of the unconscious, when they were indeed highly shaped and processed by the ego. In this view, the Surrealists may have been producing great works, but they were products of the conscious, not the unconscious mind, and they were deceiving themselves if they believed that their work represented a direct expression of the unconscious. In psychoanalysis proper, the unconscious does not just express itself automatically but can only be uncovered through the analysis of resistance and transference in the psychoanalytic process.

Notes

- â In 1917, Guillaume Apollinaire coined the term "Surrealism" in the program notes describing the ballet Parade which was a collaborative work by Jean Cocteau, Erik Satie, Pablo Picasso and LĂ©onide Massine: "From this new alliance, for until now stage sets and costumes on one side and choreography on the other had only a sham bond between them, there has come about, in Parade, a kind of super-realism ('sur-rĂ©alisme'), in which I see the starting point of a series of manifestations of this new spirit ('esprit nouveau')."

- â 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Dawn Ades, with Matthew Gale: "Surrealism," The Oxford Companion to Western Art, Hugh Brigstocke (ed.). (Oxford University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0198662037).

- â 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Calvin Tomkins, Duchamp: A Biography (Henry Holt and Company, Inc, 1996, ISBN 0805057897).

- â Paul Halsall, "Declaration of January 27, 1925" Internet Modern History Sourcebook, 1997. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- â Helena Lewis, Dada Turns Red (Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh Press, 1990). A history of the uneasy relations between Surrealists and Communists from the 1920s through the 1950s.

- â Robin D.G. Kelley, "A Poetics of Anticolonialism." Monthly Review 51 (6) (Nov. 1999). Retrieved January 17, 2018. This essay is the Introduction to the new edition of Discourse on Colonialism, by AimĂ© CĂ©saire (Monthly Review Press, 2000).

- â Robin D.G. Kelley, "Poetry and the Political Imagination: AimĂ© CĂ©saire, Negritude, & the Applications of Surrealism." 2001Retrieved June 23, 2008.

- â Marcel Duchamp, "Twelve Hundred Coal Bags Suspended from the Ceiling over a Stove" Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- â Marcel Duchamp, "Sixteen Miles of String". Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- â Germaine Greer, "Double vision: Surrealism's women thought they were celebrating sexual emancipation. But were they just fulfilling men's erotic fantasies?", Guardian Unlimited, March 5, 2007. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- â XaviĂšre Gauthier, SurrĂ©alisme et SexualitĂ©, PrĂ©face de J. B. Pontalis. (Paris: Gallimard, 1971) (in French).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alexandrian, Sarane. Surrealist Art. London: Thames & Hudson, 1970. ISBN 978-0500200971

- Appollinaire, Guillaume. Program note for Parade, printed in Oeuvres en prose complĂštes 2: 865-866, Pierre Caizergues and Michel DĂ©caudin, eds. Paris: Ăditions Gallimard (1917), 1991.

- Belton, Robert James. The Beribboned Bomb: The Image of Woman in Male Surrealist Art. University of Calgary Press, 1995. ISBN 1895176549

- Breton, André. Manifestoes of Surrealism, containing the first, second and introduction to a possible third manifesto, the novel The Soluble Fish, and political aspects of the Surrealist movement. Atlantic Books, 1970. ISBN 0472179004

- Breton, André. What is Surrealism?: Selected Writings of André Breton. Pathfinder Press, 1978. ISBN 0873488229

- Breton, André. Conversations: The Autobiography of Surrealism. (original Gallimard, 1952 in French). Da Capo Press, 1994. ISBN 1569249709

- Breton, AndrĂ©. The Abridged Dictionary of Surrealism, reprinted in: Marguerite Bonnet (ed.). Oeuvres complĂštes 1:328. Paris: Ăditions Gallimard, 1988.

- Brigstocke, Hugh (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Western Art. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0198662037

- Brotchie, Alastair and Mel Gooding, eds. A Book of Surrealist Games. Berkeley, CA: Shambhala, 1995. ISBN 1570620849

- Caws, Mary Ann. Surrealist Painters and Poets: An Anthology. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0262532013

- Durozoi, Gerard. History of the Surrealist Movement,' Translated by Alison Anderson University of Chicago Press. 2004. ISBN 0226174115

- Gauthier, XaviÚre. Surréalisme et sexualité. Préface de J. B. Pontalis. Paris: Gallimard, 1971. (in French)

- Lewis, Helena. Dada Turns Red. Edinburgh, Scotland: University of Edinburgh Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0748601349

- Lewis, Helena. The Politics Of Surrealism. St. Paul, MN: Paragon House. 1988. ISBN 978-0913729441

- Melly, George. Paris and the Surrealists. Thames & Hudson. 1991. ISBN 978-0500276389

- Moebius, Stephan. Die Zauberlehrlinge. Soziologiegeschichte des CollĂšge de Sociologie. Konstanz: UVK 2006. About the College of Sociology, its members and sociological impacts. (in German)

- Nadeau, Maurice. History of Surrealism. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 1989. ISBN 0674403452

- Short, Robert. "The Politics of Surrealism, 1920-1936." Journal of Contemporary History 1 (1966).

- Thirion, André. Revolutionaries without Revolution, Translated by Joachim Neugroschel. New York: Macmillan Publishing Co., Inc. 1972. (original in French, 1966).

- Tomkins, Calvin. Duchamp: A Biography. Henry Holt and Company, Inc, 1996. ISBN 0805057897

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- (French) Surrealism

- Surrealist.com, A general history of the art movement with artist biographies and art.

- "Herbert Marcuse and the Surrealist Revolution", an article from Arsenal/Surrealist Subversion

| Modernism | |

|---|---|

| 20th century - Modernity - Existentialism | |

| Modernism (music): 20th century classical music - Atonality - Serialism - Jazz | |

| Modernist literature - Modernist poetry | |

| Modern art - Symbolism (arts) - Impressionism - Expressionism - Cubism - Surrealism - Dadaism - Futurism (art) - Fauvism - Pop Art - Minimalism | |

| Modern dance - Expressionist dance | |

| Modern architecture - Brutalism - De Stijl - Functionalism - Futurism - Heliopolis style - International Style - Organicism - Visionary architecture | |

| ...Preceded by Romanticism | Followed by Post-modernism... |

| Western art movements |

| Renaissance · Mannerism · Baroque · Rococo · Neoclassicism · Romanticism · Realism · Pre-Raphaelite · Academic · Impressionism · Post-Impressionism |

| 20th century |

| Modernism · Cubism · Expressionism · Abstract expressionism · Abstract · Neue KĂŒnstlervereinigung MĂŒnchen · Der Blaue Reiter · Die BrĂŒcke · Dada · Fauvism · Art Nouveau · Bauhaus · De Stijl · Art Deco · Pop art · Futurism · Suprematism · Surrealism · Minimalism · Post-Modernism · Conceptual art |

|

Akhmatova's Orphans | The Beats | Black Arts Movement | Black Mountain poets | British Poetry Revival | Cairo poets | Cavalier poets | Chhayavaad | Churchyard poets | Confessionalists | Créolité | Cyclic Poets | Dadaism | Deep image | Della Cruscans | Dolce Stil Novo | Dymock poets | The poets of Elan | Flarf | Free Academy | Fugitives | Garip | Generation of '98 | Generation of '27 | Georgian poets | Goliard | The Group | Harlem Renaissance | Harvard Aesthetes | Imagism | Jindyworobak | Kimo | Lake Poets | Language poets | Martian poetry | Metaphysical poets | Misty Poets | Modernist poetry | The Movement | Négritude | New American Poetry | New Apocalyptics | New Formalism | New York School | Objectivists | Others group of artists | Parnassian poets | La Pléiade | Rhymers' Club | Rochester Poets | San Francisco Renaissance | Scottish Renaissance | Sicilian School | Sons of Ben | Southern Agrarians | Spasmodic poets | Sung poetry | Surrealism | Symbolism | Uranian poetry |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.