Impressionism

Impressionism was a nineteenth century art movement that began as a loose association of Paris-based artists who started publicly exhibiting their art in the 1860s. Characteristics of Impressionist painting include visible brush strokes, light colors, open composition, emphasis on light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subject matter, and unusual visual angles. The name of the movement is derived from Claude Monet's Impression, Sunrise (Impression, soleil levant). Critic Louis Leroy inadvertently coined the term in a satiric review published in Le Charivari.

The leading feature of impressionism is a break with a representational aesthetic, relying more on sense perception than objective verisimilitude. Impressionist works present a subject through the prism of the artist's sensibility, and through the creative process, illuminate ineffable qualities that bring delight and recognition from the observer. Impressionist aesthetic awareness spread beyond the art world, influencing music and literature. Impressionist art, music, and literature generally seek not to convey a message, but rather to evoke a mood or an atmosphere. Impressionist art has come to be prized, with works of French Impressionists mounted in the world's leading galleries and fetching millions of dollars at art auctions.

Overview

Radicals in their time, early Impressionists broke the rules of academic painting. They began by giving colors, freely brushed, primacy over line, drawing inspiration from the work of painters such as Eugene Delacroix. They also took the act of painting out of the studio and into the world. Previously, not only still-lifes and portraits, but also landscapes had been painted indoors, but the Impressionists found that they could capture the momentary and transient effects of sunlight by painting en plein air (in plain air). They used short, "broken" brush strokes of pure and unmixed color, not smoothly blended as was the custom at the time. For example, instead of physically mixing yellow and blue paint, they placed unmixed yellow paint on the canvas next to unmixed blue paint, thus mixing the colors only through one's perception of them: Creating the "impression" of green. Painting realistic scenes of modern life, they emphasized vivid overall effects rather than details.

Although the rise of Impressionism in France happened at a time when a number of other painters, including the Italian artists known as the Macchiaioli, and Winslow Homer in the United States, were also exploring plein-air painting, the Impressionists developed new techniques that were specific to the movement. Encompassing what its adherents argued was a different way of seeing, it was an art of immediacy and movement, of candid poses and compositions, of the play of light expressed in a bright and varied use of color.

The public, at first hostile, gradually came to believe that the Impressionists had captured a fresh and original vision, even if it did not meet with approval of the artistic establishment. By recreating the sensation in the eye that views the subject, rather than recreating the subject, and by creating a wealth of techniques and forms, Impressionism became seminal to various movements in painting which would follow, including Post-Impressionism, Fauvism, and Cubism.

Beginnings

In an atmosphere of change following the Revolutions of 1848, and as Emperor Napoleon III rebuilt Paris, the Académie des beaux-arts dominated the French art scene in the middle of the nineteenth century. The Académie was the upholder of traditional standards for French painting, both in content and style. Historical subjects, religious themes, and portraits were valued (landscape and still life were not), and the Académie preferred carefully finished images which mirrored reality when closely examined. Color was somber and conservative, and the traces of brush strokes were suppressed, concealing the artist's personality, emotions, and working techniques.

The Académie held an annual art show, the Salon de Paris, and artists whose works were displayed in the show won prizes, garnered commissions, and enhanced their prestige. Only art selected by the Académie jury was exhibited in the show, with the standards of the juries reflecting the values of the Académie.

The young artists painted in a lighter and brighter style than most of the generation before them, extending further the realism of Gustave Courbet and the Barbizon school. They were more interested in painting landscape and contemporary life than in recreating scenes from history. Each year, they submitted their art to the Salon, only to see the juries reject their best efforts in favor of trivial works by artists working in the approved style. A core group of young painters, Claude Monet, Pierre Auguste Renoir, Alfred Sisley, and Frédéric Bazille, who had studied under Marc-Charles-Gabriel Gleyre, became friends and often painted together. They were soon joined by Camille Pissarro, Paul Cézanne, and Armand Guillaumin.

In 1863, the jury rejected The Luncheon on the Grass (Le dĂ©jeuner sur l'herbe) by Ădouard Manet primarily because it depicted a nude woman with two clothed men on a picnic. While nudes were routinely accepted by the Salon when featured in historical and allegorical paintings, the jury condemned Manet for placing a realistic nude in a contemporary setting.[1] The jury's sharply worded rejection of Manet's painting, as well as the unusually large number of rejected works that year, set off a firestorm among French artists. Manet was admired by Monet and his friends, and led the discussions at CafĂ© Guerbois where the group of artists frequently met.

After seeing the rejected works in 1863, Emperor Napoleon III decreed that the public be allowed to judge the work themselves, and the Salon des Refusés (Salon of the Refused) was organized. While many viewers came only to laugh, the Salon des Refusés drew attention to the existence of a new tendency in art, and attracted more visitors than the regular Salon.[2]

Artists' petitions requesting a new Salon des Refusés in 1867, and again in 1872, were denied. In April of 1874, a group consisting of Monet, Renoir, Pissarro, Sisley, Cézanne, Berthe Morisot, and Edgar Degas organized their own exhibition at the studio of the photographer, Nadar. They invited a number of other progressive artists to exhibit with them, including the slightly older EugÚne Boudin, whose example had first convinced Monet to take up plein air painting years before.[3] Another painter who greatly influenced Monet and his friends, Johan Jongkind, declined to participate, as did Manet. In total, thirty artists participated in the exhibition, the first of eight that the group would present between 1874 and 1886.

After seeing the show, the critic, Louis Leroy (an engraver, painter, and successful playwright), wrote a scathing review in the Le Charivari newspaper. Among the paintings on display was Claude Monet's Impression, Sunrise (Impression, soleil levant), which became the source of the derisive title of Leroy's article, The Exhibition of the Impressionists. Leroy declared that Monet's painting was at most a sketch and could hardly be termed a finished work.

Leroy wrote, in the form of a dialog between viewers, "ImpressionâI was certain of it. I was just telling myself that, since I was impressed, there had to be some impression in it ⊠and what freedom, what ease of workmanship! Wallpaper in its embryonic state is more finished than that seascape."[4]

The term "Impressionists" quickly gained favor with the public. It was also accepted by the artists themselves, even though they were a diverse group in style and temperament, unified primarily by their spirit of independence and rebellion. Monet, Sisley, Morisot, and Pissarro may be considered the "purest" Impressionists, in their consistent pursuit of an art of spontaneity, sunlight, and color. Degas rejected much of this, as he believed in the primacy of drawing over color and belittled the practice of painting outdoors.[5] Renoir turned against Impressionism for a time in the 1880s, and never entirely regained his commitment to its ideas. Ădouard Manet, despite his role as a leader to the group, never abandoned his liberal use of black as a color, and never participated in the Impressionist exhibitions. He continued to submit his works to the Salon, where his Spanish Singer had won a 2nd class medal in 1861, and he urged the others to do likewise, arguing that "the Salon is the real field of battle" where a reputation could be made.[6]

Among the artists of the core group (minus Bazille, who had died in the Franco-Prussian War in 1870), defections occurred as CĂ©zanne, followed later by Renoir, Sisley, and Monet, abstained from the group exhibitions in order to submit their works to the Salon. Disagreements arose from issues such as Guillaumin's membership in the group, championed by Pissarro and CĂ©zanne against opposition from Monet and Degas, who thought him unworthy.[7] Degas created dissension by insisting on the inclusion of realists who did not represent Impressionist practices, leading Monet, in 1880, to accuse the Impressionists of "opening doors to first-come daubers."[8] The group divided over the invitation of Paul Signac and Georges Seurat to exhibit with them in 1886. Pissarro was the only artist to show at all eight Impressionist exhibitions.

The individual artists saw few financial rewards from the Impressionist exhibitions, but their art gradually won a degree of public acceptance. Their dealer, Paul Durand-Ruel, played a major role in gaining them acceptance as he kept their work before the public and arranged shows for them in London and New York. Although Sisley would die in poverty in 1899, Renoir had a great Salon success in 1879. Financial security came to Monet in the early 1880s and to Pissarro by the early 1890s. By this time the methods of Impressionist painting, in a diluted form, had become commonplace in Salon art.[9]

Impressionist techniques

- Short, thick strokes of paint are used to quickly capture the essence of the subject rather than its details

- Colors are applied side-by-side with as little mixing as possible, creating a vibrant surface. The optical mixing of colors occurs in the eye of the viewer.

- Grays and dark tones are produced by mixing complimentary colors. In pure Impressionism the use of black paint is avoided

- Wet paint is placed into wet paint without waiting for successive applications to dry, producing softer edges and intermingling of color

- Impressionist paintings do not exploit the transparency of thin paint films (glazes) which earlier artists built up carefully to produce effects. The surface of an Impressionist painting is typically opaque.

- The play of natural light is emphasized. Close attention is paid to the reflection of colors from object to object.

- In paintings made en plein air (outdoors), shadows are boldly painted with the blue of the sky as it is reflected onto surfaces, giving a sense of freshness and openness that was not captured in painting previously. (Blue shadows on snow inspired the technique.)

Painters throughout history had occasionally used these methods, but Impressionists were the first to use all of them together and with such boldness. Earlier artists whose works display these techniques include Frans Hals, Diego VelĂĄzquez, Peter Paul Rubens, John Constable, and J. M. W. Turner. French painters who prepared the way for Impressionism include the Romantic colorist EugĂšne Delacroix, the leader of the realists Gustave Courbet, and painters of the Barbizon school such as Theodore Rousseau. The Impressionists learned much from the work of Camille Corot and EugĂšne Boudin, who painted from nature in a style that was close to Impressionism, and who befriended and advised the younger artists.

Impressionists took advantage of the mid-century introduction of premixed paints in tubes (resembling modern toothpaste tubes) which allowed artists to work more spontaneously both outdoors and indoors. Previously, each painter made his or her own paints by grinding and mixing dry pigment powders with linseed oil.

Content and composition

Before the Impressionists, notable seventeenth-century painters had focused on common subjects, but their approach to composition was traditional. They arranged their compositions in such a way that the main subject commanded the viewer's attention. The Impressionists relaxed the boundary between subject and background so that the effect of an Impressionist painting often resembles a snapshot, a part of a larger reality captured as if by chance.[10] This was partly due to the influence of photography, which was gaining popularity. As cameras became more portable, photographs became more candid. Photography also displaced the role of the artist as a realistic chronicler of figures or scenes. Photography inspired Impressionists to capture the subjective perception, not only in the fleeting lights of a landscape, but in the day-to-day lives of people.

Another major influence was Japanese art prints (Japonism), which had originally come into the country as wrapping paper for imported goods. The art of these prints contributed significantly to the "snapshot" angles and unconventional compositions which are a characteristic of the movement. Edgar Degas was both an avid photographer and a collector of Japanese prints.[11] His The Dance Class (La classe de danse) of 1874, shows both influences in its asymmetrical composition. The dancers are seemingly caught off guard in various awkward poses, leaving an expanse of empty floor space in the lower right quadrant.

Post-Impressionism

Post-Impressionism developed from Impressionism. From the 1880s, several artists began to develop different precepts for the use of color, pattern, form, and line, derived from the Impressionist example: Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Georges Seurat, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. These artists were slightly younger than the Impressionists, and their work is known as post-Impressionism. Some of the original Impressionist artists also ventured into this new territory; Camille Pissarro briefly painted in a pointillist manner, and even Monet abandoned strict plein air painting. Paul CĂ©zanne, who participated in the first and third Impressionist exhibitions, developed a highly individual vision emphasizing pictorial structure, and he is more often called a post-Impressionist. Although these cases illustrate the difficulty of assigning labels, the work of the original Impressionist painters can by definition be categorized as Impressionism.

Painters known as Impressionists

The central figures in the development of Impressionism in France, listed alphabetically, were:

- Frédéric Bazille

- Gustave Caillebotte (who, younger than the others, joined forces with them in the mid 1870s)

- Mary Cassatt (American-born, she lived in Paris and participated in four Impressionist exhibitions)

- Paul CĂ©zanne (though he later broke away from the Impressionists)

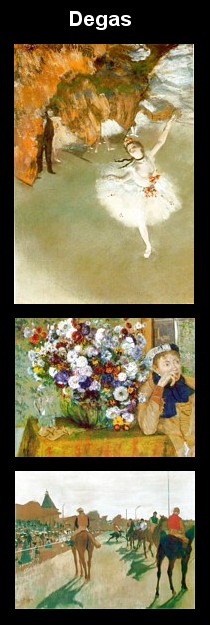

- Edgar Degas (a realist who despised the term "Impressionist," but is considered one due to his loyalty to the group)

- Armand Guillaumin

- Ădouard Manet (who did not regard himself as an Impressionist, but is generally considered one)

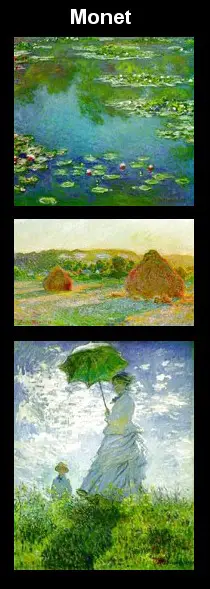

- Claude Monet (the most prolific of the Impressionists and the one who most clearly embodies their aesthetic)[12]

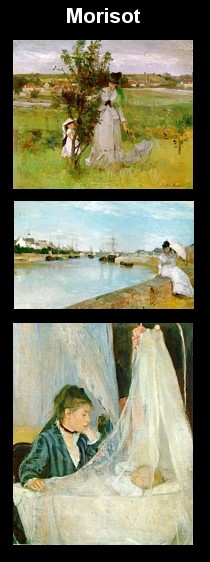

- Berthe Morisot

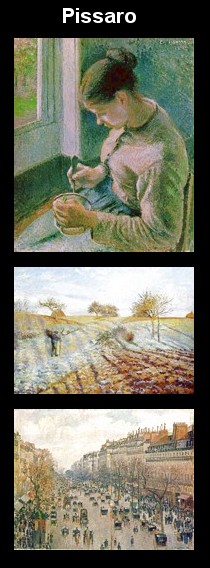

- Camille Pissarro

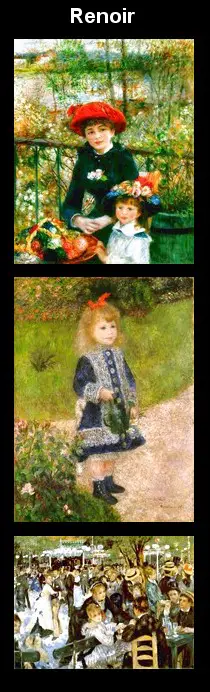

- Pierre-Auguste Renoir

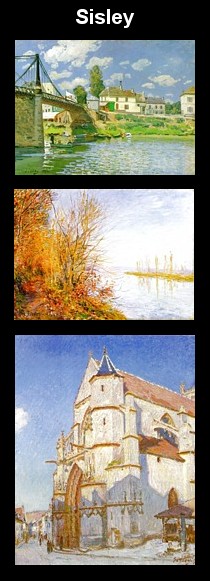

- Alfred Sisley

Among the close associates of the Impressionists were several painters who adopted their methods to some degree. These include Giuseppe De Nittis, an Italian artist living in Paris, who participated in the first Impressionist exhibit at Degas' invitation, although the other Impressionists disparaged his work.[13] Eva GonzalĂšs was a follower of Manet who did not exhibit with the group. Walter Sickert, an English friend of Degas, was also influenced by James Abbott McNeill Whistler, an American-born painter who played a part in Impressionism, although he did not join the group and preferred grayed colors. Federico Zandomeneghi was another friend of Degas who showed with the Impressionists.

By the early 1880s, Impressionist methods were affecting, at least superficially, the art of the Salon. Fashionable painters such as Jean Beraud and Henri Gervex found critical and financial success by brightening their palettes while retaining the smooth finish expected of Salon art.[14] Works by these artists are sometimes casually referred to as Impressionism, despite their remoteness from actual Impressionist practice.

As the influence of Impressionism spread beyond France, artists too numerous to list became identified as practitioners of the new style. Some of the more important examples are:

- The American Impressionists, including Frederick Carl Frieseke, Childe Hassam, Willard Metcalf, Lilla Cabot Perry, Theodore Robinson, John Henry Twachtman, and J. Alden Weir

- Lovis Corinth, Max Liebermann, and Max Slevogt in Germany

- Konstantin Korovin and Valentin Serov in Russia

- Francisco Oller y Cestero, a native of Puerto Rico who was a friend of Pissarro and CĂ©zanne

- Laura Muntz Lyall, a Canadian artist

- WĆadysĆaw PodkowiĆski, a Polish Impressionist and symbolist

- Nazmi Ziya GĂŒran, who brought Impressionism to Turkey

The sculptor Auguste Rodin is sometimes called an Impressionist for the way he used roughly modeled surfaces to suggest transient light effects. Pictorialist photographers whose work is characterized by soft focus and atmospheric effects have also been called Impressionists. Examples are Kirk Clendinning, Alvin Langdon Coburn, Robert Farber, Eduard Steichen, Alfred Stieglitz, and Clarence H. White.

Legacy

Impressionism and postimpressionism produced an aesthetic revolution. What began as a radical break from representational art developed as an increasingly accepted and indeed beloved genre of fine art painting. Building on new scientific accounts of color perception, Impressionists used a more brilliant color palette and broken brushwork to capture the transient effects of light on color and texture, and often painted out of doors rather than in the studio. The effect of this approach was to discredit academic theories of composition and appropriate subject matter.[15]

The Impressionist's concentration on perception and light influenced music and literature. In the 1860s Emile Zola praised Manet's Naturalism and claimed to have applied Impressionist techniques in his writings. Other French writers, notably Stephane Mallarmé (whom Victor Hugo called his "cher poÚte impressionniste"), Joris Karl Huysmans, and Jules Laforgue, defended the style and related it to developments in poetry, music, and philosophy. Impressionism in literature usually refers to attempts to represent through syntactic variation the fragmentary and discontinuous nature of the sensations of modern, particularly urban, civilization.[16]

Impressionism in music arose in late nineteenth century France and continued into the middle of the twentieth century, although a transference of aesthetic intention from visual to auditory medium is debatable. Originating in France, musical Impressionism is characterized by suggestion and atmosphere, and eschews the emotional excesses of the Romantic era. Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel are generally considered the greatest Impressionist composers, but Debussy disavowed the term, calling it the invention of critics. Erik Satie was also considered to be in this category although his approach was considered to be less serious, more of musical novelty in nature. Paul Dukas is another French composer sometimes considered to be an Impressionist but his style is perhaps more closely aligned to the late Romanticists. Musical Impressionism beyond France includes the work of such composers as Ralph Vaughan Williams and Ottorino Respighi.

By the 1930s impressionism had a large following, and throughout the next three decades, impressionism and postimpressionism became increasingly popular, as evidenced by the major exhibitions of Monet and Van Gogh at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in the 1980s, both of which drew enormous crowds. Record prices to date include two 1990 sales, one at Sotheby's of Renoir's Au Moulin de la Galette for $78.1 million, the other at Christie's of Van Gogh's Portrait du Dr. Gachet for $82.5 million.[17] Impressionist paintings are among the best loved in the world. Presenting a new kind of realism, Impressionists introduced a revolutionary treatment of color and light, enabling art patrons to perceive everyday life, sunlight, flowers, dappled water, nature and urban life through the filter of impression.

Notes

- â Bernard Denvir, The Thames and Hudson Encyclopaedia of Impressionism (London: Thames and Hudson, 1990, ISBN 0-500-20239-7).

- â Denvir, 194.

- â Denvir, 32.

- â John Rewald, The History of Impressionism (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1973, ISBN 0-87070-360-6).

- â Robert Gordon and Andrew Forge, Degas (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1988, ISBN 0-8109-1142-6).

- â John Richardson, Manet (Oxford: Phaidon Press Ltd, 1976, ISBN 0-7148-1743-0).

- â Denvir, (1990), 105.

- â Rewald, (1973), 603.

- â Rewald (1973), 475-476.

- â Robert Rosenblum, Paintings in the MusĂ©e d'Orsay (New York: Stewart, Tabori & Chang, 1989, ISBN 1-55670-099-7).

- â Baumann, Felix; Karabelnik, Marianne, et al., Degas Portraits (London: Merrell Holberton, 2004, ISBN 1-8594-014-1), 112.

- â Bernard Denvir (1990), 140.

- â Denvir, (1990), 152.

- â Rewald (1973), 476-477.

- â James Kerns, French Literature Companion: Impressionism. Retrieved January 13, 2009

- â Ibid.

- â Columbia Encyclopedia, Impressionism. Retrieved January 13, 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Denvir, Bernard. 1991. The Thames and Hudson Encyclopaedia of Impressionism. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20239-7.

- Moskowitz, Ira, and Maurice SĂ©rullaz. 1962. French Impressionists: A Selection of Drawings of the French 19th Century. Boston: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-58560-2.

- Gowing, Lawrence with Gotz Adriani, Mary Louise Krumrine, Mary Tompkins Lewis, Sylvie Patin, and John Rewald. 1988. Cezanne: The Early Years 1859-1872. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 0810910489.

- Rewald, John. 1973. The History of Impressionism. New York: The Museum of Modern Art. ISBN 0-87070-360-6.

External links

All links retrieved November 28, 2024.

- Mauclair, Camille (1903): The French Impressionists (1860-1900), available for free via Project Gutenberg.

- Impressionism: Paintings collected by European Museums (1999) was an art exhibition co-organized by the High Museum of Art, Atlanta, the Seattle Art Museum, and the Denver Art Museum, touring from May through December of 1999. Online guided tour.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.