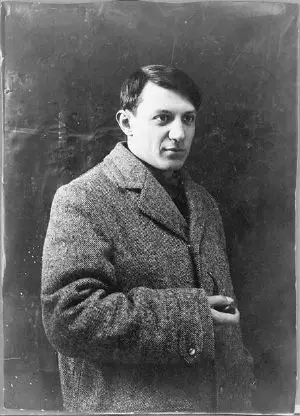

Pablo Picasso

Pablo Picasso (October 25, 1881 â April 8, 1973) was a Spanish painter and sculptor. One of the most recognized figures in twentieth century art, he is best known as the co-founder, along with Georges Braque, of cubism.

Cubism is perhaps the quintessential modernist artist movement. In cubist artworks, objects are broken up, analyzed, and re-assembled in an abstracted formâinstead of depicting objects from one viewpoint, the artist depicts the subject from a multitude of viewpoints to present the piece in a greater context. Often the surfaces intersect at seemingly random angles presenting no coherent sense of depth. The background and object (or figure) planes interpenetrate one another to create the ambiguous shallow space characteristic of cubism. The larger cultural significance of cubism pertains to the disintegration of a unified sense of the world that had pervaded European Christian culture prior to the shock of World War I.

While Picasso's influence on twentieth century art is unquestionable, the lasting significance of the deconstruction of form and meaning implicit in his art remains in question. Representational art, dating to humankind's prehistory, suggests continuity and the legitimate and coherent place of human beings within the sphere of nature. Critics have remarked that the discontinuity represented by Picasso's art reflected not only the anomie of modern life, but also the artist's own degraded moral sensibility. The breakdown of human solidarity and detachment to past and future expressed in both the artist's life and work may mirror the uncertainties of the age, yet it is questionable whether they point toward an enduring aesthetic in the visual arts.

Biography

Pablo Picasso was born in Malaga, Spain, the first child of José Ruiz y Blasco and MarÃa Picasso y López. Picasso's father was a painter whose specialty was the naturalistic depiction of birds, and who for most of his life was also a professor of art at the School of Crafts and a curator of a local museum. The young Picasso showed a passion and a skill for drawing from an early age; according to his mother, his first word was "piz," a shortening of lapiz, the Spanish word for pencil.[1] It was from his father that Picasso had his first formal academic art training, such as figure drawing and painting in oil. Although Picasso attended carpenter schools throughout his childhood, often those where his father taught, he never finished his college-level course of study at the Academy of Arts (Academia de San Fernando) in Madrid, leaving after less than a year.

After studying art in Madrid, he made his first trip to Paris in 1900, the art capital of Europe. In Paris he lived with journalist and poet Max Jacob, who helped him learn French . Max slept at night and Picasso slept during the day as he worked at night. There were times of severe poverty, cold, and desperation. Much of his work had to be burned to keep the small room warm. In 1901, with his friend, writer Francisco de Asis Soler, he founded the magazine Arte Joven in Madrid. The first edition was entirely illustrated by him. From that day, he started to simply sign his work Picasso, while before he signed Pablo Ruiz y Picasso.

In the early years of the twentieth century, Picasso, still a struggling youth, divided his time between Barcelona and Paris, where in 1904, he began a long-term relationship with Fernande Olivier. It is she who appears in many of the Rose period paintings. After acquiring fame and some fortune, Picasso left Olivier for Marcelle Humbert, whom Picasso called Eva. Picasso included declarations of his love for Eva in many Cubist works.

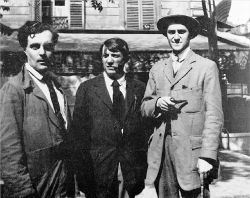

In Paris, Picasso entertained a distinguished coterie of friends in the Montmartre and Montparnasse quarters, including André Breton, poet Guillaume Apollinaire, and writer Gertrude Stein. Apollinaire was arrested on suspicion of stealing the Mona Lisa from the Louvre in 1911. Apollonaire pointed to his friend Picasso, who was also brought in for questioning, but both were later exonerated.[2]

Private life

Picasso maintained a number of mistresses in addition to his wife or primary partner. Picasso was married twice and had four children by three women. In 1918, Picasso married Olga Khokhlova, a ballerina with Sergei Diaghilev's troupe, for whom Picasso was designing a ballet, Parade, in Rome. Khokhlova introduced Picasso to high society, formal dinner parties, and all the social niceties attendant on the life of the rich in 1920s Paris. The two had a son, Paulo, who would grow up to be a dissolute motorcycle racer and chauffeur to his father. Khokhlova's insistence on social propriety clashed with Picasso's bohemian tendencies and the two lived in a state of constant conflict.

In 1927 Picasso met 17-year-old Marie-Thérèse Walter and began a secret affair with her. Picasso's marriage to Khokhlova soon ended in separation rather than divorce, as French law required an even division of property in the case of divorce, and Picasso did not want Khokhlova to have half his wealth. The two remained legally married until Khokhlova's death in 1955. Picasso carried on a long-standing affair with Marie-Thérèse Walter and fathered a daughter, Maia, with her. Marie-Thérèse lived in the vain hope that Picasso would one day marry her, and hanged herself four years after Picasso's death.

The photographer and painter Dora Maar was also a constant companion and lover of Picasso. The two were closest in the late 1930s and early 1940s and it was Maar who documented the painting of Guernica.

During the Second World War, Picasso remained in Paris while the Germans occupied the city. Picasso's artistic style did not fit the Nazi views of art, so he was not able to show his works during this time. Retreating to his studio, he continued to paint all the while. Although the Germans outlawed bronze casting in Paris, Picasso continued regardless, using bronze smuggled to him by the French Resistance.

After the liberation of Paris in 1944, Picasso began to keep company with a young art student, Françoise Gilot. The two eventually became lovers, and had two children together, Claude and Paloma. Unique among Picasso's women, Gilot left Picasso in 1953, allegedly because of abusive treatment and infidelities. This came as a severe blow to Picasso.

He went through a difficult period after Gilot's departure, coming to terms with his advancing age and his perception that, now in his seventies, he was no longer attractive, but rather grotesque to young women. A number of ink drawings from this period explore this theme of the hideous old dwarf as buffoonish counterpoint to the beautiful young girl, including several from a six-week affair with Geneviève Laporte, who in June 2005 auctioned off the drawings Picasso made of her.

Picasso was not long in finding another lover, Jacqueline Roque. Roque worked at the Madoura Pottery, where Picasso made and painted ceramics. The two remained together for the rest of Picasso's life, marrying in 1961. Their marriage was also the means of one last act of revenge against Gilot. Gilot had been seeking a legal means to legitimize her children with Picasso, Claude and Paloma. With Picasso's encouragement, she had arranged to divorce her then husband, Luc Simon, and marry Picasso to secure her children's rights. Picasso then secretly married Roque after Gilot had filed for divorce in order to exact his revenge for her leaving him.

Later life

Picasso had constructed a huge gothic structure and could afford large villas in the south of France, at Notre-dame-de-vie on the outskirts of Mougins, in the Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur. Although he was a celebrity, there was often as much interest in his personal life as his art.

In addition to his manifold artistic accomplishments, Picasso had a film career, including a cameo appearance in Jean Cocteau's Testament of Orpheus. Picasso always played himself in his film appearances. In 1955 he helped make the film Le Mystère Picasso (The Mystery of Picasso) directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot.

Pablo Picasso died on April 8, 1973 in Mougins, France, while he and his wife Jacqueline entertained friends for dinner. He was interred at Castle Vauvenargues' park, in Vauvenargues, Bouches-du-Rhône. Jacqueline Roque prevented his children Claude and Paloma from attending the funeral.

Politics

Picasso remained neutral during the Spanish Civil War, World War I, and World War II, refusing to fight for any side or country. Picasso never commented on this but encouraged the idea that it was because he was a pacifist. Some of his contemporaries though (including Braque) felt that this neutrality had more to do with cowardice than principle.

As a Spanish citizen living in France, Picasso was under no compulsion to fight against the invading Germans in either world war. In the Spanish Civil War, service for Spaniards living abroad was optional and would have involved a voluntary return to the country to join either side. While Picasso expressed anger and condemnation of Franco and the Fascists through his art, he did not take up arms against them.

He also remained aloof from the Catalan independence movement during his youth despite expressing general support for the movement and was friendly toward its activists. No political movement seemed to compel his support to any great degree, though he did become a member of the Communist Party.

During the Second World War, Picasso remained in Paris when the Germans occupied the city. The Nazis hated his style of painting, so he was not able to show his works during this time. Retreating to his studio, he continued to paint all the while. When the Germans outlawed bronze casting in Paris, Picasso was still able to continue using bronze smuggled to him by the French resistance.

After the Second World War, Picasso rejoined the French Communist Party, and even attended an international peace conference in Poland. But party criticism of him toward a portrait of Stalin judged as insufficiently realistic cooled Picasso's interest in Communist politics, though he remained a loyal member of the Communist Party until his death. His beliefs tended towards anarcho-communism.

Picasso's work

Picasso's work is often categorized into "periods." While the names of many of his later periods are debated, the most commonly accepted periods in his work are:

- Blue Period (1901â1904), consisting of somber, blue paintings influenced by a trip through Spain and the recent suicide of his friend Carlos Casagemas, often featuring depictions of acrobats, harlequins, prostitutes, beggars, and other artists.

- Rose Period (1905â1907), characterized by a more cheery style with orange and pink colors, and again featuring many harlequins. He met Fernande Olivier, a model for sculptors and artists, in Paris at this time, and many of these paintings are influenced by his warm relationship with her, in addition to his exposure to French painting.

- African-influenced Period (1908â1909), influenced by the two figures on the right in his painting, Les Demoiselles d'Avignon, which were themselves inspired by African artifacts and masks.

- Analytic Cubism (1909â1912), a style of painting he developed along with Braque using monochrome brownish colors, in which objects are taken apart and their shape "analyzed." Picasso and Braque's paintings at this time are very similar to each other.

- Synthetic Cubism (1912â1919), in which cut paper, often wallpaper or fragments of newspaper, are pasted into compositions, marking the first use of collage in fine art.

- Classicism and surrealism, "expressing a return to order" following the upheaval of World War. This period coincides with the work of many European artists in the 1920s, including Derain, Giorgio de Chirico, and the artists of the New Objectivity movement. Picasso's paintings and drawings from this period frequently recall the work of Ingres.

During the 1930s, the minotaur replaced the harlequin as a motif which he used often in his work. His use of the minotaur came partly from his contact with the surrealists, who often used it as their symbol, and appears in Picasso's Guernica.

Arguably Picasso's most famous work is his depiction of the German bombing of the town of Guernica during the Spanish Civil WarâGuernica. This large canvas embodies for many the inhumanity, brutality and hopelessness of war. Asked to explain its symbolism, Picasso said,

"It isn't up to the painter to define the symbols. Otherwise it would be better if he wrote them out in so many words! The public who look at the picture must interpret the symbols as they understand them."[3]

The act of painting was captured in a series of photographs by Picasso's lover, Dora Maar, a distinguished artist in her own right. Guernica hung in New York's Museum of Modern Art for many years. In 1981 Guernica was returned to Spain and exhibited at the Casón del Buen Retiro. In 1992 the painting hung in Madrid's Reina SofÃa Museum when it opened.

Later works

Picasso was one of 250 sculptors who exhibited in the Third Sculpture International held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in the summer of 1949. In the 1950s Picasso's style changed once again, as he took to producing reinterpretations of the art of the great masters. He made a series of works based on Velazquez's painting of Las Meninas. He also based paintings on works of art by Goya, Poussin, Manet, Courbet, and Delacroix. During this time he lived at Cannes and in 1955 helped make the film Le Mystère Picasso (The Mystery of Picasso) directed by Henri-Georges Clouzot. In addition to his manifold artistic accomplishments, Picasso had a film career, including a cameo appearance in Jean Cocteau's Testament of Orpheus. Picasso always played himself in his film appearances. From the media he received much attention, though there was often as much interest in his personal life as his art.

He was commissioned to make a maquette for a huge 50-foot high public sculpture to be built in Chicago, known usually as the Chicago Picasso. He approached the project with a great deal of enthusiasm, designing a sculpture which was ambiguous and somewhat controversial. What the figure represents is not known; it could be a bird, a horse, a woman, or a completely abstract shape, although a similar manquette of plastic 12 cm in height by Picasso is called Tête de Baboon. The huge iron sculpture, one of the most recognizable landmarks in downtown Chicago, was unveiled in 1967. Picasso refused to be paid $100,000 for it, donating it to the people of the city.

Picasso's final works were a mixture of styles, his means of expression in constant flux until the end of his life. Devoting his full energies to his work, Picasso became more daring, his works more colorful and expressive, and from 1968 through 1971 he produced a torrent of paintings and hundreds of copperplate etchings. At the time these works were dismissed by most as pornographic fantasies of an impotent old man or the slapdash works of an artist who was past his prime. One long time admirer, Douglas Cooper, called them "the incoherent scribblings of a frenetic old man." Only later, after Picasso's death, when the rest of the art world had moved on from abstract expressionism, did the critical community come to see that Picasso had already discovered neo-expressionism and was, as so often before, ahead of his time.

Pablo Picasso died on April 8, 1973 in Mougins, France, and was interred at Castle Vauvenargues' park, in Vauvenargues, Bouches-du-Rhône.

Legacy

Pablo Picasso is arguably the most influential artist of the twentieth century. A pioneering modernist, Picasso could be said to be a prophet of postmodernism, for whom the disintegration of the structures and traditions of the past implied not only loss of meaning, but moral anarchy. Unlike modernists such as T.S. Eliot, Thomas Mann, Marcel Proust, or even Franz Kafka, all of whom grappled with existential bewilderment and spiritual dislocation, Picasso found in modernism a boundaryless vista that required little acknowledgment of the context of the past. "All I have ever made," he once said, "was made for the present and in the hope that it will always remain in the present. When I have found something to express, I have done it without thinking of the past or the future."[4]

Critics have not all been kind to Picasso. According to Robert Hughes, his immense outpouring of worksâit has been estimated that Picasso produced about 13,500 paintings or designs, 100,000 prints or engravings, 34,000 book illustrations, and 300 sculptures or ceramicsâsuggest not painstaking artistry and self-surrender to creative inspiration, but promiscuous license in a brave new world of subjective expression. "The idea that painting did itself through him meant that it wasn't subject to cultural etiquette," he says. "In his work, everything is staked on sensation and desire. His aim was not to argue coherence but to go for the strongest level of feeling."[4]

Critics have noted the connection between Picasso's prodigious creative output and his insatiable personal appetites. Just as his daring works exploited rather than clarified and defined the modern loss of meaning, his extraordinary personal excesses reflected an ethic of exploitation and egoism probably unsurpassed by a major artist, according to historian Paul Johnson. An avid reader of the Marquis de Sade and a mesmerizing personality, Picasso is said to have categorized women as "goddesses and doormats," and his object, he said, was to turn the goddess into a doormat. One mistress recalled, "He first raped the woman, then he worked."[5] Following his death, one of his mistresses hanged herself; his widow shot herself; and many of his other mistresses died in poverty despite his multi-million dollar fortune. "Picasso, an atheist transfixed by primitive superstitions," writes Johnson, "lived in moral chaos and left moral chaos behind."[6]

At the time of his death many of his paintings were in his possession, as he had kept off the art market what he didn't need to sell. In addition, Picasso had a considerable collection of the work of other famous artists, some his contemporaries, including Henri Matisse, with whom he had exchanged works. Since Picasso left no will, his death duties (estate tax) to the French state were paid in the form of his works and others from his collection. These works form the core of the immense and representative collection of the Musée Picasso in Paris. In 2003, relatives of Picasso inaugurated a museum dedicated to him in his birthplace, Málaga, Spain, the Museo Picasso Málaga.

Notes

- â Robert Hughes, âAnatomy of a Minotaur,â TIME Magazine, Nov. 1, 1971. Retrieved June 28, 2007.

- â Howard Chua-Eoan Crimes of the Century, "Stealing the Mona Lisa 1911" TIME Magazine, Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- â "Guernica: Testimony of War" "Treasures of the World"PBS.org.Retrieved September 10, 2008.

- â 4.0 4.1 Robert Hughes, "Pablo Picasso Biography" artquotes.net. Retrieved October 2, 2007.

- â Paul Johnson, Creators (New York: Harper Collins, 2006), 255.

- â Johnson

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Huffington, Arianna Stassinopoulos. Picasso: Creator and Destroyer. Simon & Schuster, 1988. ISBN 0671454463

- Johnson, Paul M. Creators: From Chaucer And Durer to Picasso And Disney. New York: Harper Perrinial, 2006. ISBN 0060930462

- Kobi Ledor, MD. "A Guide to Collecting Picasso's Prints."

- Mallen, Enrique. The Visual Grammar of Pablo Picasso, vol. 54, Berkeley Insights in Linguistics & Semiotics Series. Berlin: Peter Lang, 2003.

- Mallen, Enrique. La Sintaxis de la Carne: Pablo Picasso y Marie-Thérèse Walter. Santiago de Chile: Red Internacional del Libro, 2005.

- Picasso, Olivier Widmaier. Picasso: The Real Family Story. Prestel, 2004. ISBN 3791331493

- Rubin, William, ed. Pablo Picasso, a retrospective. chronology by Jane Fluegel. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1980. ISBN 0870705199

External links

All links retrieved November 18, 2022.

- Pablo Picasso at the Metropolitan Museum of Arts, New York

- Museo Picasso Málaga (Málaga, Spain)

- Museu Picasso (Barcelona, Spain)

- Picasso at Olga's Gallery

- Power and Tenderness in Men and in Picasso's 'Minotauromachy' by Chaim Koppelman

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.