State religion

A state religion (also called an official religion, established church or state church) is a religious body or creed officially supported by the state. The term state church is associated with Christianity, and is sometimes used to denote a specific national branch of Christianity such as the Greek Orthodox Church or the Church of England. This is because in some countries national identity has historically had a specific religious identity as an inseparable component. It is also possible for a national church to be established without being under state control. In countries where state religions exist, the majority of its residents are usually adherents. A state without a state religion is called a secular state.

Nevertheless, the population's allegiance towards the state religion is often strong enough to prevent them from joining competing religious groups for fear of sanction by force. Therefore, the effect of a state religion is analogous to a chartered monopoly in the domain of religion.

While state religions encourage religious behavior in the lives of their citizens, this behavior is often artificially compelled by legal means and is not based on freedom of choice. In contrast, many modern democracies are based on constitutional models of religious pluralism, in which a variety of religious communities (rather than merely one) are accepted and protected. In such pluralistic models, religions co-exist in relative harmony and peace and there is less of a danger of religious persecution promoted by state authorities. State religions are examples of the government-sanctioned or enforced establishment of religion.

Historical Origins

Antiquity

The concept of state religion was known in ancient times in the empires of Egypt and Sumer, when every city state or people had its own god or gods. Many of the early Sumerian rulers were priests of their patron city god. Some of the earliest semi-mythological kings may have passed into the pantheon, such as Dumuzid, and some later kings came to be viewed as divine soon after their reigns, like Sargon the Great of Akkad. One of the first rulers to be proclaimed a god during his actual reign was Gudea of Lagash, followed by some later kings of Ur, such as Shulgi. Often, the state religion was integral to the power base of the reigning government, such as in Egypt, where Pharaohs were often thought of as embodiments of the god Horus.

In the Persian Empire, Zoroastrianism was the state religion of the Sassanid dynasty which lasted until 651 C.E., when Persia was conquered by the forces of Islam. However, Zoroastrianism persisted as the state religion of the independent state of Hyrcania until the 15th century.

The tiny kingdom of Adiabene in northern Mesopotamia converted to Judaism around 34 C.E.

Many of the ancient Greek city-states also had a 'god' or 'goddess' associated with their particular cities. For example, the city of Athens had Athena, Sparta had Artemis, Delos had Apollo and Artemis, and Olympia had Zeus.

China

In China, the Han Dynasty (206 B.C.E. – 220 C.E.) advocated Confucianism as the de facto state religion, establishing tests based on Confucian texts as an entrance requirement into government service. The Han emperors appreciated the societal order that is central to Confucianism. Confucianism would continue on as the state religion until the Sui Dynasty (581-618 C.E.), when it was replaced by Mahayana Buddhism. Neo-Confucianism returned as the de facto state religion sometime in the 10th century. Note however, there is a debate over whether Confucianism (including Neo-Confucianism) is a religion or merely an ethical system.

The Roman Empire

The Roman Empire, at its height, centralized and consolidated the State religion system. In Rome, the office of Pontifex Maximus came to be reserved for the emperor, who was often—declared a 'god' posthumously, or sometimes during his reign. Failure to worship the emperor as a god was at times punishable by death, as the Roman government sought to link emperor worship with loyalty to the Empire. Many Christians and Jews were subject to persecution, torture and death in the Roman Empire, because it was against their beliefs to worship the emperor.

In 311 C.E., Emperor Galerius, on his deathbed, declared a religious indulgence to Christians throughout the Roman Empire, focusing on the ending of anti-Christian persecution. Constantine I and Licinius, the two Augusti, by the Edict of Milan of 313 C.E., enacted a law allowing religious freedom to everyone within the Roman Empire. Furthermore, the Edict of Milan cited that Christians may openly practice their religion unmolested and unrestricted, and provided that properties taken from Christians be returned to them unconditionally. Although the Edict of Milan allowed religious freedom throughout the empire, it did not abolish nor disestablish the Roman state cult (Roman polytheistic paganism). The Edict of Milan was written in such a way as to implore the blessings of the deity.

Constantine called up the First Council of Nicaea in 325 C.E., although he was not a baptized Christian until years later. Despite enjoying considerable popular support, Christianity was still not the official state religion in Rome, although it was in some neighboring states such as Armenia and Aksum.

Roman religion (Neoplatonic Hellenism) was restored for a time by Julian the Apostate from 361 to 363 C.E. Julian does not appear to have reinstated the persecutions of the earlier Roman emperors.

The Christian lifestyle was generally admired and Christians managed government offices with exceptional honesty and integrity—a problem for the Empire. Roman Catholic Christianity, as opposed to Arianism and Gnosticism, was declared to be the state religion of the Roman Empire on February 27, 380 C.E. by the decree De Fide Catolica of Emperor Theodosius I.[1] This declaration was based on the idea that an official state religion would bring stability to the empire.

From State Religion to Religious State

However, the official adoption of Christianity as a state religion is also considered by many the be the beginning of the Dark Ages as the Church developed a monopoly on "truth." Augustine's City of God was seen as a justification for those Abel-type pilgrims of faith (the New Jerusalem) to use, or abuse, and eventually replace the Cain-type city of Babylon. And Rome was the battleground. The Bible was canonized and Christian writings considered heretical, esoteric (including those of women church leaders) were excluded. Non-Christian writings and science were banned. Those who did not believe the doctrines of the state religion were persecuted. Theodosius I destroyed pagan temples and converting them to Christian Churches. Such purges may have contributed to the destruction of the Library of Alexandria. The works of Aristotle and many of the Greeks were lost to the Christian world for over eight centuries.

In the Holy Roman Empire there was always an uneasy relationship between the temporal and secular rulers, the Kings and Princes, and the sacred and moral order ruled by the Popes and Bishops of the Church. By 800 C.E., the power of the Church was formidable and Charlemagne sought the blessing of the Pope on his rule. This reversal of power turned State religion into a religious State. In the Middle Ages, Western Kings often served the bidding of the Church and engaged in Crusades against the infidels, whether they profess "false religion" as the Albigenses and Cathars or control Holy lands like Jerusalem.

Eastern Orthodoxy

In the territories of the Eastern Orthodoxy, the Christianity never acquired temporal power. Political rulers, especially the Tsars in Russia, punished any attempt by religion to intervene in temporal affairs. Religion tended to spiritual life and community worship, and its focus was often on religious saints, relics, and icons and much of its aim was on the blessed afterlife to come.

Islam

Islam, which was born in the Middle Ages, initially served as a critique of the Christianity of its time. From the beginning it promoted a religious state, rather than a state religion. The idea of the dar al-islam (territory of peace) was similar to Augustine's City of God, whereas the dar al-harb was the territory of war and chaos. Islam initially embraced science, the humanities and the arts, which had been largely lost in the Christian West. And, in the early Middle Ages Islam was generally more tolerant of other beliefs and ideas, being a religion based on five actions—Shahadah, Salat, Fasting, Charity, and Pilgrimmage—rather than doctrine.

Were it not for the protection of remaining ancient texts and knowledge that reached St. Thomas Aquinas through the twelfth-century works of Ibn Rushd (Averroes), Aristotle may have been lost forever due to a fundamentalist transformation of Islam underway at that time. The jurist Al-Ghazali had condemned attempts by Al-Farabi and Avicenna to synthesize the Qur'an with Greek philosophy. While himself a mystic rather than a dogmatist, the Islamic fundamentalism of today that compares to the Christian Dark Ages is the result of a development of the doctrines of Ibn Taymiyyah through the Wahhabis and their influence on the Taliban in Afghanisatan. The destruction of Buddhist shrines and other elements of culture that do not fit the Taliban worldview, resembles the Christian purges of ancient pagan writings and symbols from the sixth century onwards.

State religions in modern nation-states

Modern nation-states are the result of a number of developments in Western civilization which include the renaissance, the reformation, the rise of city-states, the invention of the printing press which made mass education and modern bureaucracy possible, and the rise of a business class with power independent of both the state and the church. These intellectual and economic forces led to the breakdown of the monopoly on thought of the Roman Catholic Church. However, the general concept of a state religion as necessary for social order was still accepted in most of Europe.

The Protestant Reformation

The Protestant Reformation which criticized the dogmas and excesses of the papacy, sought to reform religious truth and make it more compatible with science and humanism of the period. In Germany, Martin Luther required the protection of his political ruler, Frederick the Wise, who eventually adopted Luther's Reformed Church as the state religion on his principality. Throughout Germany, Princes chose which religion would be their state religion. In exchange for protection, Luther and the German Reformation thus ceded more temporal authority to the State leading to the possibility of less of a moral check on political power. Some historians thus blame Luther for the possibility of the eventual rise of Hitler.

In Geneva, however, John Calvin was able to create a religious state, where the religious leader also held political power. His English followers, the Puritans, later sought to impose such a rule in England through Oliver Cromwell, and in the United States where they sought to create a New Israel in the New World beginning with the band of Pilgrims on the Mayflower.

In England there was the creation of a "state church" by the temporal ruler, Henry VIII, who reformed the Catholic Church to suit his political needs and created the Anglican Church, effectively replacing the Pope with the monarch.

The rise of the national idea

The breakdown of Christendom into numerous religious and cultural groups tied to smaller states as the Holy Roman Empire gradually disintegrated led to the rise of the idea of a more secular national identity and reinforced the development of the modern nation state. This idea was carried to a secular extreme in France. King Louis IV had gone farther than Henry VIII in England and declared the doctrine of "the Divine Right of Kings," which could be interpreted as meaning anything he wanted was God's will. It was similar the absolute power held by the ancient Roman Emperors. He attempted to create a French nationalism that would effectively trump Catholicism.

The excesses of the regime fomented the French Revolution whose leaders attempted to carry the idea of a secular nation-state further by creating an anti-Catholic regime based on the slogan "liberty, equality, and fraternity" and the secular cult of the decadi, which worshiped reason, established a new calendar, and promoted the decimal system. That system was inherently anarchic, unstable, and led to the endless killing of one group by the next until Napoleon seized power as Premier Consul in 1799 and later as Emperor from 1804-1814.

The French Revolution had alienated the government from the Catholic Church. Napoleon "negotiated" the Concordat of 1801 with the Pope (by physically capturing him) to bring religious and social peace to France. The Concordat essentially subordinated the economic power of the church, putting priests on the payroll of the state, making it possible for Napoleon to control through their pocketbook.

Disestablishment of Religion

"Disestablishment" is the process of divesting a church of its status as an organ of the state.

Netherlands

The disestablishment of state religion basically followed the independence of states from regimes that had been created and controlled by force. The first case came in the Netherlands, which won its independence from Spain after enduring the Eighty Year's War to liberate Dutch Calvinists from the Spanish inquisition with the Treaty of Westphalia in 1648. However, the Dutch were unable to form their own government without a guarantee of religious tolerance for those who were not Calvinists. However, the Dutch Reformed (Calvinist) Church remained the official religion of the state.

The protection of religious freedom in the Netherlands led to the inpouring of immigrants seeking greater freedom to live as they desired. The population of immigrants in Amsterdam was nearly 50 percent in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Many Jews created their own subsociety with their own laws. Huguenots from France and Puritans from England also flocked to the Netherlands.

The Netherlands quickly became a great seafaring and trading nation, becoming a thoroughly capitalist society and having the first full-time stock exchange. It did not take long for it to become a colonial empire, with colonies around the world administered by the Dutch East India Company and the Dutch West India Company. In can be argued that the separation of religious and economic power from the state led to flowering of the Dutch civilization.

The United States

The colonies in the New World had many established churches on the model of the Europeans who settled there. Plymouth, Massachusetts Bay, New Haven, and New Hampshire were founded by Puritans and Calvinists. New Netherlands was founded by Dutch Reformed Calvinists. The colonies of New York, Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia were officially Anglican.

When New France was transferred to Great Britain in 1763, the Roman Catholic Church remained under toleration, but some Huguenots were allowed entrance where they had formerly been banned from settlement by Parisian authorities. The Colony of Maryland was founded by a charter granted in 1632 to George Calvert, secretary of state to Charles I, and his son Cecil, both recent converts to Roman Catholicism. Under their leadership many English Catholic gentry families settled in Maryland. However, the colonial government was officially neutral in religious affairs, granting toleration to all Christian groups and enjoining them to avoid actions which antagonized the others. Spanish Florida was ceded to Great Britain in 1763, the British divided Florida into two colonies. Both East and West Florida continued a policy of toleration for the Catholic Residents.

The Province of Pennsylvania was founded by Quakers, but the colony never had an established church. West Jersey, also founded by Quakers, prohibited any establishment. Delaware Colony had no established church. The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations, founded by religious dissenters forced to flee the Massachusetts Bay colony, is widely regarded as the first North American polity to grant religious freedom to all its citizens.

After winning independence from Great Britain the United States created an official separation of Church and State the first clause of first amendment to its Constitution: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof." This official non-establishment was related to the new federal government only and allowed individual states to make their own decision on all social issues, such as the establishment of religion. However, migration between the states, the great "melting pot" that the United States was becoming, and the great attraction of new spiritual revivals and "awakenings" led to the gradual disestablishment of all state religions in the United States. Connecticut disestablished religion when it replaced its colonial Charter with the Connecticut Constitution of 1818; Massachusetts did not disestablish its official church until 1833, more than forty years after the ratification of the First Amendment; and local official establishments of religion persisted even later.

The Fourteenth Amendment to the US Constitution, ratified in 1868, makes no mention of religious establishment, but it opened the door the Federal Supreme Court to rule on all social issues previously left to the states and made it possible to forbid states to "abridge the privileges or immunities" of U.S. citizens, or to "deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law." This was solidified in the 1947 case of Everson v. Board of Education, when the Supreme Court held that the Fourteenth Amendment "incorporates" the First Amendment's establishment clause as applying to the states, and thereby prohibits state and local religious establishments.

The exact boundaries of this prohibition, and what was termed a "wall of seperation" are still disputed, and are a frequent source of cases before the US Supreme Court — especially as the Court must now balance, on a state (equivalent to province) level, the First Amendment prohibitions on government establishment of official religions with the First Amendment prohibitions on government interference with the free exercise of religion.

All current U.S. state constitutions include guarantees of religious liberty parallel to the First Amendment, but eight states (Arkansas, Maryland, Massachusetts, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas) also contain clauses that prohibit atheists from holding public office.[2][3] However, these clauses have been held by the United States Supreme Court to be unenforceable in the 1961 case of Torcaso v. Watkins, where the court ruled unanimously that such clauses constituted a religious test incompatible with First and Fourteenth Amendment protections.

Disestablishment and vitality of religion

The disestablishment of religion has not led to the decrease of religion as some governments have argued. Rather it has led to increased vitality of religion as people are free to seek answers to immediately pressing problems, and preachers to not succeed in gaining adherents unless their messages are relevant and provide genuine spiritual enrichment. Church attendance in the United States increased dramatically in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and much of the increase has occurred in new religious denominations: Baptist, Methodist, Unitarian, Disciples of Christ, United Church of Christ, Jehovah's Witnesses, Christian Science, and the Mormons, for example.

The United States and the Netherlands, where religious freedom has been most widely practiced also became the primary organizers of the World Council of Churches, which is a global Christian organization built from the bottom-up, rather than the traditionally top-down imposed state religions that are more instruments of control than evangelism.

State churches generally maintain the status quo. There is little incentive for clergy, who get paid a salary by a state church to update doctrine or actively recruit adherents. There is a greater likelihood that old, if not ancient, rituals will be considered more sacred as they are closer to the source of the religion. High churches and high masses exemplify this characteristic as power and authority are celebrated with pomp and ritual. Disestablished churches, on the other hand, tend to reflect the contemporary cultures in which they develop and might be criticized for their tendency towards pop culture or cultural relativism. Popular preachers, like today's televangelists, have a great impact on the people in states where religion is disestablished.

The Present Situation in Europe

Great Britain

In Great Britain, there was a campaign by Liberals, dissenters and nonconformists to disestablish the Church of England in the late 19th century; it failed in England, but demands for the measure persist to this day. The Church of Ireland was disestablished in 1869 (effective 1871). The Church of England was disestablished in Wales in 1920, the Church in Wales becoming separated from the Church of England in the process. Those who wish to continue with an established church take a position of antidisestablishmentarianism.

State religions tend to admit a larger variety of opinion within them than do traditional religious denominations. Denominations encountering major differences of opinion within themselves are likely to split; this option is not open for most state churches, so they tend to try to integrate differing opinions within themselves, the the Catholic Church did by incorporating religious orders. However, several state churches have divided, with the dissidents losing the advantages of state support. This happened with the Church of Scotland, which has split several times in the for doctrinal reasons, including the meaning and acceptability of state support. Attempts by the monarch to impose bishops on the church led to the splitting off of the Scottish Episcopal Church. Its largest offshoots from a later disruption were the Free Church of Scotland and later the United Free Church of Scotland. All of these offshoots lost the established status of their parent, but since 1929 the (partially) reunited Church of Scotland has considered itself to be a "national church" rather than an established church, as it is entirely independent of state control in spiritual matters.

A denomination's status as official religion does not always imply that the jurisdiction prohibits the existence or operation of other sects or religious bodies. It depends upon the government and the level of tolerance the citizens of that country have for each other. Some countries with official religions have laws that guarantee the freedom of worship, full liberty of conscience, and places of worship for all citizens; and implement those laws than other countries that do not have an official or established state religion.

Germany

In Germany there are two official state churches, Catholic and Reformed. Reforms under Frederick in Prussia can be compared to Napoleon's Concordat of 1801 in France. The State can fix the salaries of the clergy of the two official denominations as they do for other government employees, and they also have a right to approve a candidate's educational background and political opinions. Clergy in Germany's established religions are among the most vociferous opponents of new religious movements in Europe, like Scientology, because the spread of such religions undermines tax revenue gained from nominal members in one of the official religions that is used to support them.

Russia

In Russia as well as some of the client states of the Soviet Union, communist ideology, officially atheism and viewed as a quasi-religion itself, repressed traditional Christianity, calling it "the opiate of the masses." Clergy of the Orthodox Churches suffered several purges in which priests were killed and churches destroyed or turned into government warehouses. Unable to expunge Christianity completely, the communist regimes eventually ran the churches with religious leaders who became members of the communist party.

When Communism regimes collapsed in the 1980s, leaders sought to establish religious pluralism and religious freedom in an attempt to prevent a return a society like that under the Czars. However, under Boris Yeltsin and Vladimir Putin, the Russian Orthodox Church has received federal funding for rebuilding churches, and the lines of establishment are blurred. Under Gorbachev's perestroika small religions were free to practice and even received some state support to neutralize the power of the Russian Orthodox Church, however under Boris Yeltsin, a law was passed that a religion had to prove 50,000 adherents to get state support, giving them quasi-establishment status and having the effect of suppressing the smaller religious movements.

Pupils in Belograd, Bryansk, Kaluga, and Smolensk regions are being taught Orthodox Christianity in public schools,[4] much like Lutheranism is taught in Finland. The fluid situation has been decentralized through the 86 regions and republics, as 10 percent of the population is Muslim and Muslim leaders have asked for lessons on Islamic culture to be provided.

Much of the violence following the break-up of Soviet Union and the collapse of Yugoslavia has been rooted in the attempt by religious and secular national groups fighting over whose identity can be imposed as the official cultural identity of the state.

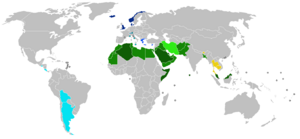

Current Global overview

Christian countries

The following states recognize some form of Christianity as their state or official religion (listed by denomination):

Roman Catholic

Jurisdictions which recognize Roman Catholicism as their state or official religion: Argentina, Bolivia, Costa Rica, El Salvador, Liechtenstein, Malta, Monaco, Slovakia, some cantons of Switzerland, and Vatican City.

Eastern Orthodox

Jurisdictions which recognize one of the Eastern Orthodox Churches as a state religion: Cyprus, Moldova, Greece, Finland along with Lutheranism, Russian Federation alongside Judaism, Islam, and Buddhism.

Lutheran

Jurisdictions which recognize a Lutheran church as their state religion: Denmark, Iceland, Norway, Finland.

Anglican

Jurisdictions that recognise an Anglican church as their state religion: England.

Reformed

Jurisdictions which recognize a Reformed church as their state religion: Scotland, some cantons of Switzerland.

Old Catholic

Jurisdictions which recognize an Old Catholic church as their state religion: Some cantons of Switzerland.

Islamic countries

Countries which recognize Islam as their official religion. Although these are religious states, rather than state religions: Afghanistan, Algeria (Sunni), Bahrain, Bangladesh, Brunei, Comoros (Sunni), Egypt, Iran (Shi'a), Iraq, Jordan(Sunni), Kuwait, Libya, Malaysia (Sunni), Maldives, Mauritania (Sunni), Morocco, Oman, Pakistan (Sunni), Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia (Sunni), Tunisia, United Arab Emirates, Yemen.

Buddhism as state religion

Governments which recognize Buddhism, either a specific form of, or the whole, as their official religion: Bhutan, Cambodia[5], Kalmykia[6], Sri Lanka [7], Thailand, Tibet Government in Exile (Gelugpa school of Tibetan Buddhism).

Hinduism as a State religion

- Nepal was once the world's only Hindu state, but has ceased to be so following a declaration by the Parliament in 2006.

States without any state religion

These states do not profess any state religion, and are generally secular or laist. Countries which officially decline to establish any religion include: Australia, Azerbaijan, Canada, Chile, Cuba, China, France, India, Ireland, Israel[8], Jamaica, Japan[9], Kosovo[10], Lebanon[11], Mexico, Montenegro, Nepal[12], New Zealand, Nigeria, North Korea, Romania, Russia, Singapore, South Africa, South Korea, Spain, Turkey, United States, Venezuela, Vietnam.

Established churches and former state churches

| Country | Church | Denomination | Disestablished |

|---|---|---|---|

| Albania | none since independence | n/a | n/a |

| Anhalt | Evangelical Church of Anhalt | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Armenia | Armenian Apostolic Church | Oriental Orthodox | 1921 |

| Austria | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1918 |

| Baden | Roman Catholic Church and the Evangelical Church of Baden | Catholic and Lutheran | 1918 |

| Bavaria | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1918 |

| Brazil | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1890 |

| Brunswick-Lüneburg | Evangelical Lutheran State Church of Brunswick | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Bulgaria | Bulgarian Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | 1946 |

| Chile | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1925 |

| Cuba | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1902 |

| Cyprus | Cypriot Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | 1977 |

| Czechoslovakia | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1920 |

| Denmark | Church of Denmark | Lutheran | no |

| England | Church of England | Anglican | no |

| Estonia | Church of Estonia | Eastern Orthodox | 1940 |

| Finland[13] | Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland | Lutheran | 1870/1919 |

| France[14] | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1905 |

| Georgia | Georgian Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | 1921 |

| Greece | Greek Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | no |

| Guatemala | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1871 |

| Haiti | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1987 |

| Hesse | Evangelical Church of Hesse and Nassau | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Hungary[15] | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1848 |

| Iceland | Lutheran Evangelical Church | Lutheran | no |

| Ireland | Church of Ireland | Anglican | 1871 |

| Italy | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1984 |

| Lebanon | Maronite Catholic Church/Islam | Catholic/Islam | no |

| Liechtenstein | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | no |

| Lippe | Church of Lippe | Reformed | 1918 |

| Lithuania | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1940 |

| Lübeck | North Elbian Evangelical Church | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Luxembourg | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | ? |

| Republic of Macedonia | Macedonian Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | no |

| Malta | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | no |

| Mecklenburg | Evangelical Church of Mecklenburg | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Mexico | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1874 |

| Monaco | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | no |

| Mongolia | Buddhism | n/a | 1926 |

| Netherlands | Dutch Reformed Church | Reformed | 1795 |

| Norway | Church of Norway | Lutheran | no |

| Oldenburg | Evangelical Lutheran Church of Oldenburg | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Panama | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1904 |

| Philippines[16] | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1902 |

| Poland | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1939 |

| Portugal | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1910 |

| Prussia | 13 provincial churches | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Romania | Romanian Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | 1947 |

| Russia | Russian Orthodox Church | Eastern Orthodox | 1917 |

| Thuringia | Evangelical Church in Thuringia | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Saxony | Evangelical Church of Saxony | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Schaumburg-Lippe | Evangelical Church of Schaumburg-Lippe | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Scotland[17] | Church of Scotland | Presbyterian | no |

| Serbia | Serbian Orthodox Church | Eastern | ? |

| Spain | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1978 |

| Sweden | Church of Sweden | Lutheran | 2000 |

| Switzerland | none since the adoption of the Federal Constitution (1848) | n/a | n/a |

| Turkey | Islam | Islam | 1928 |

| Uruguay | Roman Catholic Church | Catholic | 1919 |

| Waldeck | Evangelical Church of Hesse-Kassel and Waldeck | Lutheran | 1918 |

| Wales[18] | Church in Wales | Anglican | 1920 |

| Württemberg | Evangelical Church of Württemberg | Lutheran | 1918 |

Notes

- ↑ Halsall, Paul (June 1997). Theodosian Code XVI.i.2. Medieval Sourcebook: Banning of Other Religions. Fordham University. Retrieved Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ↑ State Constitutions that Discriminate Against Atheists. www.godlessgeeks.com. Retrieved Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ↑ Religious laws and religious bigotry - Religious discrimination in U.S. state constitutions. www.religioustolerance.com. Retrieved Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ↑ Religion enters Russian schools, BBC News, August, 31, 2006. Retrieved August 28, 2008.

- ↑ Constitution of Cambodia, constitution.org. Retrieved Retrieved August 9, 2008. (Article 43)

- ↑ a republic within the Russian Federation (Tibetan Buddhism - sole Buddhist entity in Europe)

- ↑ (Theravada Buddhism- he constitution accords Buddhism the "foremost place," but Buddhism is not recognized as the state religion., "Chapter II — Buddhism"The Constitution of the Republic of Sri lanka, The Official Website of the Government of Sri Lanka. Retrieved Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ↑ Israel is defined in several of its laws as a democratic Jewish state. However, the term "Jewish" is a polyseme that can relate equally to the Jewish people or religion. As of 2007, there is no civil marriage in Israel, although there is recognition of marriages performed abroad.

- ↑ From the Meiji era to the first part of the Showa era in Japan, Koshitsu Shinto was established as the national religion. According to this, the emperor of Japan was an arahitogami, an incarnate divinity and the offspring of goddess Amaterasu. As the emperor was, according to the constitution, "head of the empire" and "supreme commander of the Army and the Navy," every Japanese citizen had to obey his will and show absolute loyalty until the end of World War II.

- ↑ Draft Constitution of the Republic of Kosovo Retrieved August 9, 2008.

- ↑ (although president must always remain a Maronite Catholic, and prime minister a Sunni Muslim)

- ↑ (declared a secular state on May 18, 2006, by the newly resumed House of Representatives)

- ↑ Finland's State Church was the Church of Sweden until 1809. As an autonomous Grand Duchy under Russia 1809-1917, Finland retained the Lutheran State Church system, and a state church separate from Sweden, later named the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland, was established. It was detached from the state as a separate judicial entity when the new church law came to force in 1870. After Finland had gained independence in 1917, religious freedom was declared in the constitution of 1919 and a separate law on religious freedom in 1922. Through this arrangement, the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland lost its position as a state church but gained a constitutional status as a national church alongside with the Finnish Orthodox Church, whose position however is not codified in the constitution.

- ↑ In France, the Concordat of 1801 made the Roman Catholic, Calvinist and Lutheran churches state-sponsored religions, as well as Judaism.

- ↑ In Hungary, the constitutional laws of 1848 declared five established churches on equal status: the Roman Catholic, Calvinist, Lutheran, Eastern Orthodox and Unitarian Church. In 1868 the law was ratified again after the Ausgleich. In 1895 Judaism was also recognized as the sixth established church. In 1948 every distinction between the different denominations were abolished.

- ↑ Disestablished by the Philippine Organic Act of 1902.

- ↑ The Church of Scotland is "established" in the sense that its system of church courts was set up by Parliament, but over the centuries it has resisted interference by secular authorities. The Church of Scotland Act 1921 recognizes its exclusive authority to decide ecclesiastical issues, and the statute incorporates and accepts the Church's Declaratory Articles as lawful.

- ↑ The Church in Wales was split from the Church of England in 1920 by Welsh Church Act 1914; at the same time becoming disestablished.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Berg, Thomas C. (2004). The State and Religion in a Nutshell. West Group Publishing. ISBN 978-0314148858

- Brown, L. Carl. (2001). Religion and State. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0231120395

- Fox, Jonathan. (2008). A World Survey of Religion and the State. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521707589

- Hasson, Kevin Seamus. (2005). The Right to Be Wrong: Ending the Culture War Over Religion in America. Encounter Books. ISBN 1-59403-083-9

External links

- McConnell, Michael W. (2003). Establishment and Disestablishment at the Founding, Part I: Establishment of Religion. William and Mary Law Review, provided by Questia.com 44 (5): 2105. Retrived on June 12, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.