Dutch East India Company

The Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oostindische Compagnie or VOC in old-spelling Dutch) chartered by the States-General of the Netherlands to expand trade and assure close relations between the government and its colonial enterprises in Asia. The company was granted a monopoly on Dutch trade East of the Cape of Good Hope and West of the Straits of Magellan. It was the first multinational corporation in the world and the first company to issue stock.

It remained an important trading concern for almost two centuries, paying an 18 percent annual dividend for almost 200 years, until it became bankrupt and was formally dissolved in 1800,[1] its possessions and the debt being taken over by the government of the Batavian Republic. The VOC's territories became the Dutch East Indies and were expanded over the course of the nineteenth century to include the whole of the Indonesian archipelago, and in the twentieth century would form Indonesia. The Dutch East India Company impacted on European life, changing its food (adding spice). It also stimulated the development of scholarly interest in the languages, cultures and religions of the territories it acquired within the Dutch academy, to a degree almost unrivaled elsewhere in Europe. It enhanced the status of Holland within Europe, despite the nation's modest size.

History

Background

The United Provinces of the Netherlands were being pressured to expand overseas.[2] By the end of the sixteenth-century Dutch merchants had acquired large amounts of capital from their successful European trade, and were looking for new investment opportunities. The highly profitable sea trade routes between Europe and Asia had been established and dominated by the Portuguese. Reconnoitering in the late sixteenth century paved the way for Houtman's voyage to Banten, the chief port of Java, and back (1595‚Äď1597), which became quite profitable.

In 1596, a group of Dutch merchants decided to try to circumvent the monopoly. In 1596, a four-ship expedition led by Cornelis de Houtman was the first Dutch contact with Indonesia. The expedition reached Banten, the main pepper port of West Java, where they clashed with both the Portuguese and indigenous Indonesians. It then sailed east along the north coast of Java, losing twelve crew to a Javanese attack at Sidayu and killing a local ruler in Madura. Half the crew were lost before the expedition made it back to the Netherlands the following year, but with enough spices to make a considerable profit.

In 1598, an increasing number of new fleets were sent out by competing merchant groups from all around the Netherlands. Some fleets were lost, but most were successful. In March 1599, a fleet of 22 ships under Jacob van Neck of five different companies was the first Dutch fleet to reach the ‚ÄėSpice Islands‚Äô of Maluku. The ships returned to Europe in 1599 and 1600 and although eight ships were lost, the expedition made a 400 percent profit[3] In 1600, the Dutch joined forces with the local Hituese (near Ambon) in an anti-Portuguese alliance, in return for which the Dutch were given the sole right to purchase spices from Hitu.

Dutch control of Ambon was achieved in alliance with Hitu when in February 1605, they prepared to attack a Portuguese fort in Ambon but the Portuguese surrendered. In 1613, the Dutch expelled the Portuguese from their Solor fort, but were expelled again in 1636 following a re-occupation.[4]

Formation

At the time, it was customary for a company to be set up only for the duration of a single voyage, and to be liquidated right after the return of the fleet. As the competition between companies intensified, the profitability of the new trade was threatened, but consolidation was not possible as the merchants of different provinces were unwilling to cooperate.

In 1602, the Dutch government forced the issue, sponsoring the creation of a single "United East Indies Company" that was granted a monopoly over the Asian trade.

In 1603, the first permanent Dutch trading post in Indonesia was established in Banten, West Java and in 1611, another was established at Jayakarta. In 1610, the VOC established the post of Governor General to enable firmer control of their affairs in Asia. To advise and control the risk of despotic Governors General, a Council of the Indies (Raad van Indi√ę) was created. The Governor General effectively became the main administrator of the VOC's activities in Asia, although the Heeren XVII continued to officially have overall control.[5]

VOC headquarters were in Ambon for the tenures of the first three Governor Generals, but it was not a satisfactory location. Although it was at the center of the spice production areas, it was far from the Asian trade routes and other VOC areas of activity ranging from Africa to Japan. A location in the west of the archipelago was thus sought; the Straits of Malacca were strategic, but had become dangerous following the Portuguese conquest and the first permanent VOC settlement in Banten was controlled by a powerful local ruler and subject to stiff competition from Chinese and English traders.

In 1604, a British East India Company voyage commanded by Sir Henry Middleton reached the islands of Ternate, Tidore, Ambon, and Banda; in Banda, they encountered severe VOC hostility, which saw the beginning of Anglo-Dutch competition for access to spices. From 1611 to 1617, the English established trading posts at Sukadana (southwest Kalimantan), Makassar, Jayakarta and Jepara in Java, and Aceh, Pariaman and Jambi in (Sumatra) which threatened Dutch ambitions for a monopoly on East Indies trade. Diplomatic agreements in Europe in 1620 ushered in a period of cooperation between the Dutch and the English over the spice trade. This ended with a notorious, but disputed incident, known as the 'Amboyna massacre', where ten English and ten Japanese traders were arrested, tried and beheaded for conspiracy against the Dutch government.[6] Although this caused outrage in Europe and a diplomatic crisis, the English quietly withdrew from most of their Indonesian activities (except trading in Bantam) and focused on other Asian interests.

In 1619, Jan Pieterszoon Coen was appointed Governor-General of the VOC. He was not afraid to use brute force to put the VOC on a firm footing. On May 30 that year, Coen, backed by a force of nineteen ships, stormed Jayakarta driving out the Banten forces, and from the ashes, established Batavia as the VOC headquarters. In the 1620s, almost the entire native population of Banda Islands, the source of nutmeg was deported, driven away, starved to death or killed in an attempt to replace them with Dutch colonial slave labor.

The VOC traded throughout Asia. Ships coming into Batavia from the Netherlands carried silver from Spanish mines in Peru and supplies for VOC settlements in Asia. Silver, combined with copper from Japan, was used to trade with India and China for textiles. These products, such as cotton, silk and ceramics, were either traded within Asia for the coveted spices or brought back to Europe. The VOC was also instrumental in introducing European ideas and technology to Asia. The Company supported Christian missionaries and traded modern technology with China and Japan.

A more peaceful VOC trade post on Dejima, an artificial island off the coast of Nagasaki, was for a long time the only place where Europeans were permitted to trade with Japan.

In 1640, the VOC obtained the port of Galle, Sri Lanka, from the Portuguese and broke the latter's monopoly of the cinnamon trade. In 1658, Gerard Hulft laid siege to Colombo, which was captured with the help of King Rajasinghe II of Kandy. By 1659, the Portuguese had been expelled from the coastal regions, which were then occupied by the VOC, securing for it the monopoly over cinnamon.

In 1652, Jan van Riebeeck established an outpost at the Cape of Good Hope to re-supply VOC ships on their journey to East Asia. This post later became a fully-fledged colony, the Cape Colony, when more Dutch and other Europeans started to settle there. VOC outposts were also established in Persia (now Iran), Bengal (now Bangladesh, but then part of India), Malacca (Melaka, now in Malaysia), Siam (now Thailand), mainland China (Canton), Formosa (now Taiwan) and southern India. In 1662, Koxinga expelled the Dutch from Taiwan.

By 1669, the VOC was the richest private company the world had ever seen, with over 150 merchant ships, 40 warships, 50,000 employees, a private army of 10,000 soldiers, and a dividend payment of 40 percent.

Decline

From 1720 on, the market for sugar from Indonesia declined as the competition from cheap sugar from Brazil increased and European markets became saturated. Dozens of Chinese sugar traders went bankrupt which led to massive unemployment, which in turn led to gangs of unemployed coolies. The Dutch government in Batavia did not adequately respond to these problems. In 1740, rumours of deportation of the gangs from the Batavia area led to widespread rioting. The Dutch military searched houses of Chinese in Batavia searching for weapons. When a house accidentally burnt down, military and impoverished citizens started slaughtering and pillaging the Chinese community. This incident was deemed sufficiently serious for the board of the VOC to start an official investigation into the Government of the Dutch East Indies for the first time in its history.

During the eighteenth century, the possessions of the Company were increasingly focused on the East Indies. After the fourth war between the United Provinces and Great Britain (1780‚Äď1784), the VOC got into financial trouble, and in 1800,[7] the company was dissolved, four years after the States-General were replaced by the French supported Batavian Republic. This was soon replaced by French occupation. After the defeat of the French empire, the previously privately owned East Indies territories were granted to the newly created Kingdom of the Netherlands by the Congress of Vienna in 1815.

Organization

The VOC consisted of six Chambers (Kamers) in port cities: Amsterdam, Delft, Rotterdam, Enkhuizen, Middelburg, and Hoorn. Delegates of these chambers convened as the Heeren XVII (the Lords Seventeen).

Of the Heeren XVII, eight delegates were from the Chamber of Amsterdam (one short of a majority on its own), four from the Chamber of Zeeland, and one from each of the smaller Chambers, while the seventeenth seat was alternatively from the Chamber of Zeeland or rotated among the five small Chambers. Amsterdam had thereby the decisive voice. The Zeelanders in particular had misgivings about this arrangement at the beginning. The fear was not unfounded, because in practice it meant Amsterdam stipulated what happened.

The six chambers raised the start-up capital of the Dutch East India Company:

| Chamber | Capital (Guilders) |

|---|---|

| Amsterdam | 3,679,915 |

| Zeeland | 1,300,405 |

| Enkhuizen | 540,000 |

| Delft | 469,400 |

| Hoorn | 266,868 |

| Rotterdam | 173,000 |

| Total: | 6,424,588 |

The raising of capital in Rotterdam did not go so smoothly. A considerable part originated from inhabitants of Dordrecht. Although it did not raise as much capital as Amsterdam or Zeeland, Enkhuizen had the largest input in the share capital of the VOC. Under the first 358 shareholders, there were many small entrepreneurs, who dared to take the risk.

Among the early shareholders of the VOC, immigrants played an important role. Under the 1,143 tenderers were 39 Germans and no fewer than 301 Zuid-Nederlanders (roughly present Belgium and Luxemburg, then under Habsburg rule), of whom Isaäc le Maire was the largest subscriber with ƒ85,000. VOC's total capitalization was ten times that of its British rival.

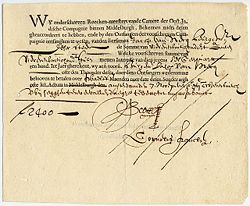

The logo of the VOC consisted of a large capital 'V' with an O on the left and a C on the right leg. The first letter of the hometown of the chamber conducting the operation was placed on top (see figure for example of the Amsterdam chamber logo). The flag of the company was orange, white, blue (see Dutch flag) with the company logo embroidered on it.

The Heeren XVII (Lords Seventeen) met alternately six years in Amsterdam and two years in Middelburg. They defined the VOC's general policy and divided the tasks among the Chambers. The Chambers carried out all the necessary work, built their own ships and warehouses and traded the merchandise. The Heeren XVII sent the ships' masters off with extensive instructions on the route to be navigated, prevailing winds, currents, shoals and landmarks. The VOC also produced its own charts.

In the context of the Dutch-Portuguese War the company established its headquarters in Batavia, Java (now Jakarta, Indonesia). Other colonial outposts were also established in the East Indies, such as on the Spice Islands (Moluccas), which include the Banda Islands, where the VOC forcibly maintained a monopoly over nutmeg and mace. Methods used to maintain the monopoly included the violent suppression of the native population, not stopping short of extortion and mass murder.

Notable VOC ships

- Replicas have been constructed of several VOC ships, marked with an (R)

- Amsterdam (R)

- Arnhem

- Batavia (R)

- Braek

- Duyfken ("Little Dove") (R)

- Eendracht (1615) ("Unity")

- Galias

- Grooten Broeck ("Great Brook")

- Gulden Zeepaert ("Golden Seahorse")

- Halve Maen ("Half moon") (R)

- Heemskerck

- Hollandia

- Klein Amsterdam ("Small Amsterdam")

- Leeuwerik ("Lark")

- Leyden

- Limmen

- Pera

- Prins Willem (R)

- Ridderschap van Holland ("Knighthood of Holland")

- Rooswijk

- Sardam

- Texel

- Utrecht

- Vergulde Draeck ("Gilded Dragon")

- Vianen

- Vliegende Hollander ("Flying Dutchman")

- Vliegende Swaan ("Flying Swan")

- Wapen van Hoorn ("Arms of Hoorn")

- Wezel ("Weasel")

- Zeehaen ("Sea Cock")

- Zeemeeuw ("Seagull")

- Zuytdorp ("South Village")

Gallery: VOC multi-national outposts

VOC logo in Tainan Old Fort of Anping, Taiwan

VOC logo in Cape Town Castle or Castle of Good Hope (c. 1680), South Africa

VOC logo on cannon at Dejima in Nagasaki harbour, Japan (1764)

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ M. C. Rickles, A History of Modern Indonesia Since C. 1300. (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780804721950)

- ‚ÜĎ M. C. Rickles, A History of Modern Indonesia Since C. 1300. (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780804721950), 6.

- ‚ÜĎ M. C. Rickles, A History of Modern Indonesia Since C. 1300. (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780804721950), 27.

- ‚ÜĎ M. C. Rickles, A History of Modern Indonesia Since C. 1300. (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780804721950), 28.

- ‚ÜĎ M. C. Rickles, A History of Modern Indonesia Since C. 1300. (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780804721950), 28.

- ‚ÜĎ George Miller, To the Spice Islands and Beyond Travels in Eastern Indonesia. (Oxford in Asia paperbacks. Kuala Lumpur: Oxford University Press, 1996. ISBN 9789676530998)

- ‚ÜĎ M. C. Rickles, A History of Modern Indonesia Since C. 1300. (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780804721950), 110.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boxer, C. R. The Dutch Seaborne Empire, 1600-1800. Pelican books. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1973. ISBN 978-0140216004

- Gaastra, Femme S. The Dutch East India Company Expansion and Decline. Zutphen: Walburg Pers, 2003. ISBN 978-9057302411

- Liu, Yong. The Dutch East India Company's Tea Trade with China, 1757-1781. TANAP monographs on the history of the Asian-European interaction, v. 6. Leiden: Brill, 2007. ISBN 978-9004155992

External links

All links retrieved February 12, 2024.

- A taste of adventure ‚ÄĒ The history of spices is the history of trade

- Dutch Portuguese Colonial History

- Why did the Largest Corporation in the World go Broke?

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.