Difference between revisions of "Meaning of life" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) (import from wiki) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (118 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

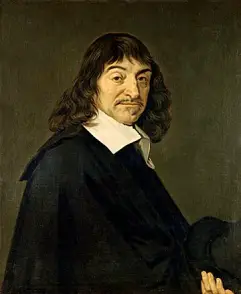

| + | [[File:Paul Gauguin - D'ou venons-nous.jpg|thumb|450px|''[[Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?]]'', one of [[Post-Impressionist]] [[Paul Gauguin]]'s most famous paintings]] | ||

| + | The question of the '''meaning of life''' is perhaps the most fundamental "why?" in human existence. It relates to the purpose, use, value, and reason for individual existence and that of the [[universe]]. | ||

| + | This question has resulted in a wide range of competing answers and explanations, from [[science|scientific]] to [[philosophy|philosophical]] and [[religion|religious]] explanations, to explorations in [[literature]]. Science, while providing theories about the How and What of life, has been of limited value in answering questions of meaning—the Why of human existence. Philosophy and religion have been of greater relevance, as has literature. Diverse philosophical positions include essentialist, [[existentialism|existentialist]], [[skepticism|skeptic]], [[nihilism|nihilist]], [[pragmatism|pragmatist]], [[humanism|humanist]], and [[atheism|atheist]]. The essentialist position, which states that a purpose is given to our life, usually by a supreme being, closely resembles the viewpoint of the [[Abrahamic religions]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | While philosophy approaches the question of meaning by reason and reflection, religions approach the question from the perspectives of [[revelation]], [[enlightenment (concept)|enlightenment]], and doctrine. Generally, religions have in common two most important teachings regarding the meaning of life: 1) the ethic of the reciprocity of [[love]] among fellow [[human]]s for the purpose of uniting with a [[God|Supreme Being]], the provider of that ethic; and 2) spiritual formation towards an [[afterlife]] or eternal life as a continuation of physical life. | ||

| − | + | == Scientific Approaches to the Meaning of Life == | |

| + | [[Science]] cannot possibly give a direct answer to the question of meaning. There are, strictly speaking, no scientific views on the meaning of [[biology|biological]] life other than its observable biological function: to continue. Like a judge confronted with a conflict of interests, the honest scientist will always make the difference between his personal opinions or feelings and the extent to which science can support or undermine these beliefs. That extent is limited to the discovery of ways in which things (including human life) came into being and objectively given, observable laws and patterns that might hint at a certain origin and/or purpose forming the ground for possible meaning. | ||

| − | + | === What is the origin of life? === | |

| − | + | The question "What is the [[origin of life]]?" is addressed in the sciences in the areas of [[cosmogeny]] (for the origins of the universe) and [[abiogenesis]] (for the origins of biological life). Both of these areas are quite hypothetical—cosmogeny, because no existing physical model can accurately describe the very early universe (the instant of the [[Big Bang]]), and abiogenesis, because the environment of the young earth is not known, and because the conditions and chemical processes that may have taken billions of years to produce life cannot (as of yet) be reproduced in a laboratory. It is therefore not surprising that scientists have been tempted to use available data both to support and to oppose the notion that there is a given purpose to the emergence of the cosmos. | |

| − | + | === What is the nature of life? === | |

| + | Toward answering "What is the nature of life (and of the universe in which we live)?," scientists have proposed various theories or worldviews over the centuries. They include, but are not limited to, the [[heliocentrism|heliocentric view]] by [[Copernicus]] and [[Galileo]], through the [[mechanism (philosophy)|mechanistic clockwork universe]] of [[René Descartes]] and [[Isaac Newton]], to [[Albert Einstein]]'s theory of [[general relativity]], to the [[quantum mechanics]] of [[Werner Heisenberg|Heisenberg]] and [[Erwin Schrödinger|Schrödinger]] in an effort to understand the universe in which we live. | ||

| − | + | Near the end of the twentieth century, equipped with insights from the gene-centered view of evolution, biologists began to suggest that in so far as there may be a primary function to life, it is the survival of [[genes]]. In this approach, success isn't measured in terms of the survival of species, but one level deeper, in terms of the successful replication of genes over the eons, from one species to the next, and so on. Such positions do not and cannot address the issue of the presence or absence of a purposeful origin, hence meaning. | |

| − | + | === What is valuable in life? === | |

| − | + | Science may not be able to tell us what is most valuable in life in a philosophical sense, but some studies bear on related questions. Researchers in [[positive psychology]] study factors that lead to life satisfaction (and before them less rigorously in [[humanistic psychology]]), in [[social psychology]] factors that lead to infants thriving or failing to thrive, and in other areas of [[psychology]] questions of motivation, preference, and what people value. [[economics|Economists]] have learned a great deal about what is valued in the marketplace; and [[sociology|sociologists]] examine value at a social level using theoretical constructs such as [[Value theory#Sociology|value theory]], norms, anomie, etc. | |

| − | == | + | === What is the purpose of, or in, (one's) life? === |

| − | + | [[Natural science|Natural scientists]] look for the purpose of life within the structure and function of life itself. This question also falls upon social scientists to answer. They attempt to do so by studying and explaining the behaviors and interactions of human beings (and every other type of animal as well). Again, science is limited to the search for elements that promote the purpose of a specific life form (individuals and societies), but these findings can only be suggestive when it comes to the overall purpose and meaning. | |

| − | + | === Analysis of teleology based on science === | |

| + | [[Teleology]] is a philosophical and theological study of purpose in nature. Traditional philosophy and Christian theology in particular have always had a strong tendency to affirm teleological positions, based on observation and belief. Since [[David Hume]]’s [[skepticism]] and [[Immanuel Kant]]’s [[agnosticism|agnostic]] conclusions in the eighteenth century, the use of teleological considerations to prove the existence of a purpose, hence a purposeful creator of the universe, has been seriously challenged. Purpose-oriented thinking is a natural human tendency which Kant already acknowledged, but that does not make it legitimate as a scientific explanation of things. In other words, teleology can be accused of amounting to wishful thinking. | ||

| + | The alleged "debunking" of teleology in science received a fresh impetus from advances in biological knowledge such as the publication of [[Charles Darwin]]'s ''On the Origin of Species'' (i.e., [[natural selection]]). Best-selling author and evolutionary biologist [[Richard Dawkins]] puts forward his explanation based on such findings. Ironically, it is also science that has recently given a new impetus to teleological thinking by providing data strongly suggesting the impossibility of random development in the creation of the universe and the appearance of life (e.g., the "[[anthropic principle]]"). | ||

| + | ==Philosophy of the Meaning of Life== | ||

| + | While [[science|scientific]] approaches to the meaning of life aim to describe relevant [[empiricism|empirical]] facts about human existence, [[philosopher]]s are concerned about the relationship between ideas such as the proper interpretation of empirical data. Philosophers have considered such questions as: "Is the question 'What is the meaning of life?' a meaningful question?"; "What does it really mean?"; and "If there are no objective values, then is life meaningless?" Some philosophical disciplines have also aimed to develop an understanding of life that explains, regardless of how we came to be here, what we should do, now that we are here. | ||

| − | + | Since the question about life’s meaning inevitably leads to the question of a possible divine origin to life, philosophy and [[theology]] are inextricably linked on this issue. Whether the answer to the question about a divine creator is yes, no, or "not applicable," the question will come up. Nevertheless, philosophy and [[religion]] significantly differ in much of their approach to the question. Hence, they will be treated separately. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Essentialist views=== | |

| + | [[Image: Descartes.jpg|thumb|300 px| [[René Descartes]]]] | ||

| − | + | Essentialist views generally start with the assumption that there is a common essence in human beings, human nature, and that this nature is the starting point for any evaluation of the meaning of life. In classic philosophy, from [[Plato]]'s [[idealism]] to [[Descartes]]' [[rationalism]], humans have been seen as rational beings or "rational animals." Conforming to that inborn quality is then seen as the aim of life. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Reason]], in that context, also has a strong value-oriented and [[ethics|ethical]] connotation. Philosophers such as [[Socrates]], Plato, Descartes, [[Baruch Spinoza|Spinoza]], and many others had views about what sort of life is best (and hence most meaningful). [[Aristotle]] believed that the pursuit of happiness is the ''Highest Good,'' and that such is achievable through our uniquely human capacity to reason. The notion of the highest good as the rational aim in life can still be found in later thinkers like [[Kant]]. A strong ethical connotation can be found in the Ancient [[Stoicism|Stoics]], while [[Epicureanism]] saw the meaning of life in the search for the highest pleasure or [[happiness]]. | |

| − | + | All these views have in common the assumption that it is possible to discover, and then practice, whatever is seen as the highest good through rational [[insight]], hence the term "philosophy"—the love of wisdom. With Plato, the wisdom to discover the true meaning of life is found in connection with the notion of the [[immortality|immortal]] [[soul]] that completes its course in earthly life once it liberates itself from the futile earthly goals. In this, Plato prefigures a theme that would be essential in [[Christianity]], that of [[God]]-given eternal life, as well as the notion that the soul is [[good]] and the flesh [[evil]] or at least a hindrance to the fulfillment of one’s true goal. At the same time, the concept that one has to rise above deceptive appearances to reach a proper understanding of life’s meaning has links to Eastern and Far Eastern traditions. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In medieval and [[modern philosophy]], the Platonic and Aristotelian views were incorporated in a worldview centered on the [[theism|theistic]] concept of the [[Will of God]] as the determinant factor for the meaning of our life, which was then seen as achieving moral perfection in ways pleasing to [[God]]. Modern philosophy came to experience considerable struggle in its attempt to make this view compatible with the rational discourse of a philosophy free of any [[prejudice]]. With Kant, the given of a God and his will fell away as a possible rational certainty. Certainty concerning purpose and meaning were moved from God to the immediacy of [[consciousness]] and [[conscience]], as epitomized in Kant’s teaching of the [[categorical imperative]]. This development would gradually lead to the later supremacy of an [[existentialism|existentialist]] discussion of the meaning of life, since such a position starts with the self and its choices, rather than with a purpose given "from above." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The emphasis on meaning as destiny, rather than choice, would one more time flourish in the early nineteenth century’s ''German Idealism'', notably in the philosophy of [[Hegel]] where the overall purpose of history is seen as the embodiment of the ''Absolute Spirit'' in human society. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Existentialist views=== |

| − | + | {{main|Existentialism}} | |

| − | + | [[Image: Kierkegaard.jpg|thumb|300 px|Sketch of [[Søren Kierkegaard]]]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Existentialism|Existentialist]] views concerning the meaning of life are based on the idea that it is only personal choices and commitments that can give any meaning to life since, for an individual, life can only be his or her life, and not an abstractly given entity. By going this route, existentialist thinkers seek to avoid the trappings of dogmatism and pursue a more genuine route. That road, however, is inevitably filled with doubt and hesitation. With the refusal of committing oneself to an externally given ideal comes the limitation of certainty to that alone which one chooses. | |

| − | + | Presenting essentialism and existentialism as strictly divided currents would undoubtedly amount to a caricature, hence such a distinction can only be seen as defining a general trend. It is very clear, however, that philosophical thought from the mid-nineteenth century on has been strongly marked by the influence of existentialism. At the same time, the motives of dread, loss, uncertainty, and anguish in the face of an existence that needs to be constructed “out of nothing” have become predominant. These developments also need to be studied in the context of modern and contemporary [[history|historical]] events leading to the World Wars. | |

| − | + | A universal existential contact with the question of meaning is found in situations of extreme distress, where all expected goals and purposes are shattered, including one’s most cherished hopes and convictions. The individual is then left with the burning question whether there still remains an even more fundamental, self-transcending meaning to existence. In many instances, such existential crises have been the starting point for a qualitative transformation of one’s perceptions. | |

| − | + | [[Søren Kierkegaard]] invented the term "leap of faith" and argued that life is full of [[Absurdism|absurdity]] and the individual must make his or her own values in an indifferent world. For Kierkegaard, an individual can have a meaningful life (or at least one free of despair) if the individual relates the self in an unconditional commitment despite the inherent vulnerability of doing so in the midst our [[doubt]]. Genuine meaning is thus possible once the individual reaches the third, or religious, stage of life. Kirkegaard’s sincere commitment, far remote from any ivory tower philosophy, brings him into close contact with religious-philosophical approaches in the Far East, such as that of [[Buddhism]], where the attainment of true meaning in life is only possible when the individual passes through several stages before reaching enlightenment that is fulfillment in itself, without any guarantee given from the outside (such as the certainty of [[salvation]]). | |

| − | + | Although not generally categorized as an existentialist philosopher, [[Arthur Schopenhauer]] offered his own bleak answer to "what is the meaning of life?" by determining one's visible life as the reflection of one's will and the Will (and thus life) as being an aimless, irrational, and painful drive. The essence of reality is thus seen by Schopenhauer as totally negative, the only promise of salvation, deliverance, or at least escape from suffering being found in world-denying existential attitudes such as aesthetic contemplation, sympathy for others, and [[asceticism]]. | |

| − | + | Twentieth-century thinkers like [[Martin Heidegger]] and [[Jean-Paul Sartre]] are representative of a more extreme form of existentialism where the existential approach takes place within the framework of [[atheism]], rather than [[Christianity]]. [[Gabriel Marcel]], on the other hand, is an example of Christian existentialism. For [[Paul Tillich]], the meaning of life is given by one’s inevitable pursuit of some ''ultimate concern,'' whether it takes on the traditional form of religion or not. Existentialism is thus an orientation of the mind that can be filled with the greatest variety of content, leading to vastly different conclusions. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Skeptical and nihilist views=== | |

| + | {{main|Skepticism|Nihilism}} | ||

| + | [[Image: Friedrich_Nietzsche_drawn_by_Hans_Olde.jpg|thumb|300 px|Portrait of [[Friedrich Nietzsche]] by [[Hans Olde]]]] | ||

| − | + | '''Skepticism''' | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Skepticism]] has always been a strong undercurrent in the history of thought, as uncertainty about meaning and purpose has always existed even in the context of the strongest commitment to a certain view. Skepticism can also be called an everyday existential reality for every human being, alongside whatever commitments or certainties there may be. To some, it takes on the role of doubt to be overcome or endured. To others, it leads to a negative conclusion concerning our possibility of making any credible claim about the meaning of our life. | |

| − | + | Skepticism in philosophy has existed since antiquity where it formed several schools of thought in [[Greece]] and in [[Rome]]. Until recent times, however, overt skepticism has remained a minority position. With the collapse of traditional certainties, skepticism has become increasingly prominent in social and cultural life. Ironically, because of its very nature of denying the possibility of certain knowledge, it is not a position that has produced major thinkers, at least not in its pure form. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The philosophy of [[Ludwig Wittgenstein]] and [[logical positivism]], as well as the whole tradition of [[analytical philosophy]] represent a particular form of skepticism in that they challenge the very meaningfulness of questions like "the meaning of life," questions that do not involve verifiable statements. | |

| − | + | '''Nihilism''' | |

| − | + | Whereas skepticism denies the possibility of certain knowledge and thus rejects any affirmative statement about the meaning of life, [[nihilism]] amounts to a flat denial of such meaning or value. [[Friedrich Nietzsche]] characterized nihilism as emptying the world and especially human existence of meaning, purpose, comprehensible truth, or essential value. The term ''nihilism'' itself comes from the [[Latin language|Latin]] ''nihil,'' which means "nothing." | |

| − | + | Nihilism thus explores the notion of [[existence]] without meaning. Though nihilism tends toward [[defeatism]], one can find strength and reason for celebration in the varied and unique human relationships it explores. From a nihilist point of view, morals are valueless and only hold a place in society as false ideals created by various forces. The characteristic that distinguishes nihilism from other skeptical or relativist philosophies is that, rather than merely insisting that values are subjective or even unwarranted, nihilism declares that nothing is of value, as the name implies. | |

| − | === | + | ===Pragmatist views=== |

| + | {{main|Pragmatism}} | ||

| + | Pragmatic philosophers suggest that rather than a truth about life, we should seek a useful understanding of life. [[William James]] argued that truth could be made but not sought. Thus, the meaning of life is a belief about the purpose of life that does not contradict one's experience of a purposeful life. Roughly, this could be applied as: "The meaning of life is those purposes which cause you to value it." To a pragmatist, the meaning of life, your life, can be discovered only through experience. | ||

| − | + | [[Pragmatism]] is a school of philosophy which originated in the [[United States]] in the late 1800s. Pragmatism is characterized by the insistence on consequences, utility and practicality as vital components of truth. Pragmatism objects to the view that human concepts and intellect represent reality, and therefore stands in opposition to both formalist and rationalist schools of philosophy. Rather, pragmatism holds that it is only in the struggle of intelligent organisms with the surrounding environment that theories and data acquire significance. Pragmatism does not hold, however, that just anything that is useful or practical should be regarded as true, or anything that helps us to survive merely in the short-term; pragmatists argue that what should be taken as true is that which most contributes to the most human good over the longest course. In practice, this means that for pragmatists, theoretical claims should be tied to verification practices—i.e., that one should be able to make predictions and test them—and that ultimately the needs of humankind should guide the path of human inquiry. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | ===Humanistic views=== | |

| + | {{main|Humanism}} | ||

| + | Human purpose is determined by humans, completely without supernatural influence. Nor does knowledge come from supernatural sources, it flows from human observation, experimentation, and rational analysis preferably utilizing the scientific method: the nature of the universe is what we discern it to be. As are [[ethics|ethical]] values, which are derived from human needs and interests as tested by experience. | ||

| − | + | Enlightened self-interest is at the core of [[humanism]]. The most significant thing in life is the [[human being]], and by extension, the human race and the environment in which we live. The [[happiness]] of the individual is inextricably linked to the well-being of humanity as a whole, in part because we are social animals which find meaning in relationships, and because cultural progress benefits everybody who lives in that [[culture]]. | |

| − | + | When the world improves, life in general improves, so, while the individual desires to live well and fully, humanists feel it is important to do so in a way that will enhance the well-being of all. While the evolution of the human species is still (for the most part) a function of nature, the evolution of humanity is in our hands and it is our responsibility to progress it toward its highest ideals. In the same way, humanism itself is evolving, because humanists recognize that values and ideals, and therefore the meaning of life, are subject to change as our understanding improves. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The doctrine of humanism is set forth in the "Humanist Manifesto" and "A Secular Humanist Declaration." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Atheistic views=== | ===Atheistic views=== | ||

{{main|Atheism}} | {{main|Atheism}} | ||

| − | [[Atheism]] | + | [[Atheism]] in its strictest sense means the belief that no [[God]] or Supreme Being (of any type or number) exists, and by extension that neither the universe nor its inhabitants were created by such a Being. Because atheists reject supernatural explanations for the existence of life, lacking a deistic source, they commonly point to blind [[abiogenesis]] as the most likely source for the origin of life. As for the purpose of life, there is no one particular atheistic view. Some atheists argue that since there are no gods to tell us what to value, we are left to decide for ourselves. Other atheists argue that some sort of meaning can be intrinsic to life itself, so the existence or non-existence of God is irrelevant to the question (a version of [[Socrates]]’ ''Euthyphro dilemma''). Some believe that life is nothing more than a byproduct of insensate natural forces and has no underlying meaning or grand purpose. Other atheists are indifferent towards the question, believing that talking about meaning without specifying "meaning to whom" is an incoherent or incomplete thought (this can also fit with the idea of choosing the meaning of life for oneself). |

| − | == | + | ==Religious Approaches to the Meaning of Life== |

| − | + | The [[religion|religious]] traditions of the world have offered their own [[doctrine|doctrinal]] responses to the question about life’s meaning. These answers also remain independently as core statements based on the claim to be the product of [[revelation]] or [[enlightenment]], rather than [[human]] reflection. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | === | + | ===Abrahamic religions=== |

| − | + | [[Image:ReligionSymbolAbr.PNG|thumb|350px|right|Symbols of the three main [[Abrahamic religions]] – [[Christianity]], [[Judaism]], and [[Islam]]]] | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | ====Judaism==== |

| + | [[Judaism]] regards life as a precious gift from [[God]]; precious not only because it is a gift from God, but because, for humans, there is a uniqueness attached to that gift. Of all the creatures on Earth, humans are created in the [[image of God]]. Our lives are sacred and precious because we carry within us the divine image, and with it, unlimited potential. | ||

| − | + | While Judaism teaches about elevating yourself in spirituality, connecting to God, it also teaches that you are to [[love]] your neighbor: "Do not seek revenge or bear a grudge against one of your people, but love your neighbor as yourself" ([[Leviticus]] 19:18). We are to practice it in this world ''Olam Hazeh'' to prepare ourselves for ''Olam Haba'' (the world to come). | |

| − | + | [[Kabbalah]] takes it one step further. The [[Zohar]] states that the reason for life is to better one's soul. The soul descends to this world and endures the trials of this life, so that it can reach a higher spiritual state upon its return to the source. | |

| − | === | + | ====Christianity==== |

| − | + | [[Christians]] draw many of their beliefs from the [[Bible]], and believe that loving God and one's neighbor is the meaning of life. In order to achieve this, one would ask God for the forgiveness of one's own sins, and one would also forgive the sins of one's fellow humans. By forgiving and loving one's neighbor, one can receive God into one's heart: "But love your enemies, do good to them, and lend to them without expecting to get anything back. Then your reward will be great, and you will be sons of the Most High, because he is kind to the ungrateful and wicked" ([[Gospel of Luke|Luke]] 6:35). Christianity believes in an eternal [[afterlife]], and declares that it is an unearned gift from God through the love of [[Jesus Christ]], which is to be received or forfeited by [[faith]] ([[Ephesians]] 2:8-9; [[Epistle to the Romans|Romans]] 6:23; [[Gospel of John|John]] 3:16-21; 3:36). | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | [[ | + | Christians believe they are being tested and purified so that they may have a place of responsibility with Jesus in the eternal Kingdom to come. What the Christian does in this life will determine his place of responsibility with Jesus in the eternal [[Kingdom of God|Kingdom]] to come. Jesus encouraged Christians to be overcomers, so that they might share in the glorious reign with him in the life to come: "To him who overcomes, I will give the right to sit with me on my throne, just as I overcame and sat down with my Father on his throne" ([[Book of Revelation|Revelation]] 3:21). |

| − | + | The Bible states that it is God "in whom we live and move and have our being" ([[Book of Acts|Acts]] 17:28), and that to fear God is the beginning of [[wisdom]], and to depart from [[evil]] is the beginning of understanding ([[Book of Job|Job]] 28:28). The Bible also says, "Whether therefore ye eat, or drink, or whatsoever ye do, do all to the glory of God" ([[First Epistle to the Corinthians|1 Corinthians]] 10:31). | |

| − | === | + | ====Islam==== |

| − | + | In [[Islam]] the ultimate objective of man is to seek the pleasure of [[Allah]] by living in accordance with the divine guidelines as stated in the [[Qur'an]] and the tradition of the Prophet. The Qur'an clearly states that the whole purpose behind the creation of man is for glorifying and worshipping Allah: "I only created jinn and man to worship Me" (Qur'an 51:56). Worshiping in Islam means to testify to the oneness of God in his lordship, names and attributes. Part of the divine guidelines, however, is [[almsgiving]] ''(zakat),'' one of the [[Pillars of Islam|Five Pillars of Islam]]. Also regarding the ethic of reciprocity among fellow humans, the Prophet teaches that "None of you [truly] believes until he wishes for his brother what he wishes for himself." <ref>[https://www.iium.edu.my/deed/hadith/other/hadithnawawi.html An-Nawawi's Forty Hadiths (Translation)] ''International Islamic Publishing House''. Retrieved June 28, 2021.</ref> To [[Muslim]]s, life was created as a test, and how well one performs on this test will determine whether one finds a final home in [[Jannah]] (Heaven) or [[Jahannam]] (Hell). | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The esoteric Muslim view, generally held by [[Sufi]]s, the universe exists only for God's pleasure. | |

| − | + | ===South Asian religions=== | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Hinduism==== | |

| + | For [[Hindus]], the purpose of life is described by the ''[[purusharthas]]'', the four ends of human life. These goals are, from lowest to highest importance: ''[[Kāma]]'' (sensual pleasure or love), ''[[Artha]]'' (wealth), ''[[Dharma]]'' (righteousness or morality) and ''[[Moksha]]'' (liberation from the cycle of [[reincarnation]]). ''Dharma'' connotes general [[morality|moral]] and [[ethics|ethical]] ideas such as honesty, responsibility, respect, and care for others, which people fulfill in the course of life as a householder and contributing member of society. Those who renounce home and career practice a life of meditation and austerities to reach ''Moksha''. | ||

| − | + | [[Hinduism]] is an extremely diverse religion. Most Hindus believe that the spirit or soul—the true "self" of every person, called the [[ātman]]—is eternal. According to the [[Monism|monistic]]/[[Pantheism|pantheistic]] theologies of Hinduism (such as the [[Advaita Vedanta]] school), the ātman is ultimately indistinct from [[Brahman]], the supreme spirit. Brahman is described as "The One Without a Second"; hence these schools are called "[[Dualism#Consciousness/Matter dualism|non-dualist]]." The goal of life according to the Advaita school is to realize that one's ātman (soul) is identical to Brahman, the supreme soul. The [[Upanishads]] state that whoever becomes fully aware of the ātman as the innermost core of one's own self, realizes their identity with Brahman and thereby reaches ''Moksha'' (liberation or freedom).<ref>Thomas Merton, ''Thoughts on the East'' (New York City: New Directions Publishing, 1995, ISBN 978-0811212939).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | Other Hindu schools, such as the [[Dualism#Consciousness/Matter dualism|dualist]] [[Dvaita|Dvaita Vedanta]] and other [[bhakti]] schools, understand Brahman as a Supreme Being who possesses personality. On these conceptions, the ātman is dependent on Brahman, and the meaning of life is to achieve ''Moksha'' through love towards God and on God's grace. | |

| − | + | Whether non-dualist ''(Advaita)'' or dualist ''(Dvaita),'' the bottom line is the idea that all humans are deeply interconnected with one another through the unity of the ātman and Brahman, and therefore, that they are not to injure one another but to care for one another. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Jainism==== | |

| + | [[Jainism]] teaches that every [[human]] is responsible for his or her actions. The Jain view of [[karma]] is that every action, every word, every thought produces, besides its visible, an invisible, transcendental effect on the soul. The ethical system of Jainism promotes self-discipline above all else. By following the [[asceticism|ascetic]] teachings of the ''[[Tirthankara]]'' or ''Jina,'' the 24 enlightened spiritual masters, a human can reach a point of [[enlightenment (concept)|enlightenment]], where he or she attains infinite knowledge and is delivered from the cycle of [[reincarnation]] beyond the yoke of karma. That state is called ''Siddhashila.'' Although Jainism does not teach the existence of God(s), the ascetic teachings of the ''Tirthankara'' are highly developed regarding right faith, right knowledge, and right conduct. The meaning of life consists in achievement of complete enlightenment and bliss in ''Siddhashila'' by practicing them. | ||

| − | + | Jains also believe that all living beings have an eternal [[soul]], ''[[jiva|jīva]]'', and that all souls are equal because they all possess the potential of being liberated. So, Jainism includes strict adherence to ''[[ahimsa]]'' (or ''ahinsā''), a form of [[nonviolence]] that goes far beyond [[vegetarianism]]. Food obtained with unnecessary cruelty is refused. Hence the universal ethic of reciprocity in Jainism: "Just as pain is not agreeable to you, it is so with others. Knowing this principle of equality treat other with respect and compassion" (Saman Suttam 150). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ====Buddhism==== |

| − | + | One of the central views in [[Buddhism]] is a nondual worldview, in which subject and object are the same, and the sense of doer-ship is illusionary. On this account, the meaning of life is to become enlightened as to the nature and oneness of the universe. According to the [[scripture]]s, the [[Gautama Buddha|Buddha]] taught that in life there exists ''[[dukkha]]'', which is in essence sorrow/suffering, that is caused by [[tanha|desire]] and it can be brought to cessation by following the [[Noble Eightfold Path]]. This teaching is called the ''Catvāry Āryasatyāni'' (Pali: {{unicode|''Cattāri Ariyasaccāni''}}), or the "[[Four Noble Truths]]": | |

| − | + | [[Image:Dharma wheel.svg|thumb|350px|right|The eight-spoked [[Dharmacakra]]. The eight spokes represent the [[Noble Eightfold Path]] of [[Buddhism]].]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | # There is suffering ''(dukkha)'' | |

| + | # There is a cause of suffering—[[Tanha|craving]] ''(trishna)'' | ||

| + | # There is the cessation of suffering ''(nirodha)'' | ||

| + | # There is a way leading to the cessation of suffering—the Noble Eightfold Path | ||

| − | + | [[Theravada|Theravada Buddhism]] promotes the concept of ''Vibhajjavada'' (literally, "teaching of analysis"). This doctrine says that insight must come from the aspirant's experience, critical investigation, and reasoning instead of by blind faith; however, the scriptures of the Theravadin tradition also emphasize heeding the advice of the wise, considering such advice and evaluation of one's own experiences to be the two tests by which practices should be judged. The Theravadin goal is liberation (or freedom) from suffering, according to the Four Noble Truths. This is attained in the achievement of ''[[Nirvana]],'' which also ends the [[reincarnation|repeated cycle]] of birth, old age, sickness and death. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Mahayana|Mahayana Buddhist]] schools de-emphasize the traditional Theravada ideal of the release from individual suffering ''(dukkha)'' and attainment of awakening ''(Nirvana).'' In Mahayana, the Buddha is seen as an eternal, immutable, inconceivable, omnipresent being. The fundamental principles of Mahayana doctrine are based around the possibility of universal [[liberation]] from suffering for all beings, and the existence of the transcendent [[Buddha-nature]], which is the eternal Buddha essence present, but hidden and unrecognized, in all living beings. Important part of the Buddha-nature is [[compassion]]. | |

| − | + | Buddha himself talks about the ethic of reciprocity: "One who, while himself seeking happiness, oppresses with violence other beings who also desire happiness, will not attain happiness hereafter." (Dhammapada 10:131).<ref>[http://www.urbandharma.org/pdf/dpada.pdf The Dhammapada: The Buddha's Path of Wisdom] ''Buddhist Publication Society'', 1985. Retrieved June 28, 2021.</ref> | |

| − | + | ====Sikhism==== | |

| + | [[Sikhism]] sees life as an opportunity to understand God the Creator as well as to discover the divinity which lies in each individual. God is omnipresent ''(sarav viāpak)'' in all creation and visible everywhere to the spiritually awakened. Guru Nanak Dev stresses that God must be seen from "the inward eye," or the "heart," of a human being: devotees must [[meditation|meditate]] to progress towards enlightenment. In this context of the omnipresence of God, humans are to love one another, and they are not enemies to one another. | ||

| − | + | According to Sikhism, every creature has a [[soul]]. In death, the soul passes from one body to another until final [[liberation]]. The journey of the soul is governed by the [[karma]] of the deeds and actions we perform during our lives, and depending on the goodness or wrongdoings committed by a person in their life they will either be rewarded or punished in their [[reincarnation|next life]]. As the spirit of God is found in all life and matter, a soul can be passed onto other life forms, such as plants and insects - not just human bodies. A person who has evolved to achieve spiritual perfection in his lifetimes attains salvation – union with God and liberation from rebirth in the material world. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | ''[[ | + | ===East Asian religions=== |

| + | [[Image:Yin yang.svg|right|thumb|350px|In [[Taoism]], the ''[[Taijitu]]'' symbolizes the [[unity of opposites]] between ying and yang, described in the theory of the [[Taiji]].]] | ||

| − | + | ====Confucianism==== | |

| + | [[Confucianism]] places the meaning of life in the context of human relationships. People's character is formed in the given relationships to their parents, siblings, spouse, friends and social roles. There is need for discipline and education to learn the ways of harmony and success within these social contexts. The purpose of life, then, is to fulfill one's role in society, by showing [[honesty]], propriety, politeness, [[filial piety]], [[loyalty]], humaneness, benevolence, etc. in accordance with the order in the cosmos manifested by ''[[Tian]]'' (Heaven). | ||

| − | + | Confucianism deemphasizes afterlife. Even after humans pass away, they are connected with their descendants in this world through rituals deeply rooted in the virtue of filial piety that closely links different generations. The emphasis is on normal living in this world, according to the contemporary scholar of Confucianism Wei-Ming Tu, "We can realize the ultimate meaning of life in ordinary human existence."<ref>Wei-Ming Tu, ''Confucian Thought: Selfhood as Creative Transformation'' (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985, ISBN 978-0887060069).</ref> | |

| − | + | ====Daoism==== | |

| + | The [[Daoism|Daoist]] [[cosmogony]] emphasizes the need for all humans and all sentient beings to return to the ''primordial'' or to rejoin with the ''Oneness'' of the Universe by way of self-correction and self realization. It is the objective for all adherents to understand and be in tune with the ''Dao'' (Way) of nature's ebb and flow. | ||

| − | + | Within the theology of Daoism, originally all humans were beings called ''yuanling'' ("original spirits") from ''Taiji'' and ''[[Dao|Tao]],'' and the meaning in life for the adherents is to realize the temporal nature of their existence, and all adherents are expected to practice, hone and conduct their mortal lives by way of ''Xiuzhen'' (practice of the truth) and ''Xiushen'' (betterment of the self), as a preparation for spiritual transcendence here and hereafter. | |

| − | + | ==The Meaning of Life in Literature== | |

| − | + | Insight into the meaning of life has been a central preoccupation of literature from ancient times. Beginning with [[Homer]] through such [[twentieth-century]] writers as [[Franz Kafka]], authors have explored ultimate meaning through usually indirect, "representative" depictions of life. For the ancients, human life appeared within the matrix of a cosmological order. In the dramatic saga of war in Homer's ''[[Illiad]],'' or the great human tragedies of Greek playwrights such as [[Sophocles]], [[Aeschylus]], and [[Euripides]], inexorable Fate and the machinations of the Gods are seen as overmastering the feeble means of mortals to direct their destiny. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In the Middle Ages, [[Dante]] grounded his epic ''[[Divine Comedy]]'' in an explicitly Christian context, with meaning derived from moral discernment based on the immutable laws of God. The Renaissance humanists [[Miguel de Cervantes]] and [[William Shakespeare]] influenced much later literature by more realistically portraying human life and beginning an enduring literary tradition of elevating human experience as the grounds upon which meaning may be discerned. With notable exceptions—such as satirists such as [[François-Marie Voltaire]] and [[Jonathan Swift]], and explicitly Christian writers such as [[John Milton]]—Western literature began to examine human experience for clues to ultimate meaning. Literature became a methodology to explore meaning and to represent truth by holding up a mirror to human life. | |

| − | + | In the nineteenth century [[Honoré de Balzac]], considered one of the founders of [[literary realism]], explored French society and studied human psychology in a massive series of novels and plays he collectively titled ''[[The Human Comedy]]''. [[Gustave Flaubert]], like Balzac, sought to realistically analyze French life and manners without imposing preconceived values upon his object of study. | |

| − | '' | ||

| − | |||

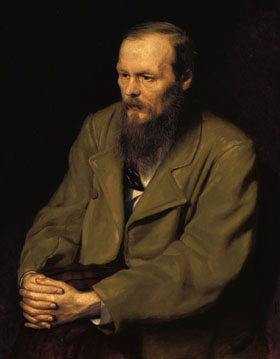

| − | + | [[Image:Dostoevsky 1872.jpg|thumb|350 px|[[Fyodor Dostoevsky]]. Portrait by [[Vasily Perov]], 1872]] | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Novelist [[Herman Melville]] used the quest for the White Whale in ''[[Moby-Dick]]'' not only as an explicit symbol of his quest for the truth but as a device to discover that truth. The literary method became for Melville a process of philosophic inquiry into meaning. [[Henry James]] made explicit this important role in "The Art of Fiction" when he compared the novel to fine art and insisted that the novelist's role was exactly analogous to that of the artist or philosopher: | |

| − | The | + | <blockquote>"As people feel life, so they will feel the art that is most closely related to it. ... Humanity is immense and reality has a myriad forms; ... Experience is never limited and it is never complete; it is an immense sensibility, a kind of huge spider-web, of the finest silken threads, suspended in the chamber of consciousness.<ref>Henry James, [https://public.wsu.edu/~campbelld/amlit/artfiction.html The Art of Fiction] ''Longman's Magazine'' 4 (September 1884). Retrieved June 28, 2021.</ref></blockquote> |

| − | < | ||

| − | + | Realistic novelists such as [[Leo Tolstoy]] and especially [[Fyodor Dostoevsky]] wrote "novels of ideas," recreating Russian society of the late nineteenth century with exacting verisimilitude, but also introducing characters who articulated essential questions concerning the meaning of life. These questions merged into the dramatic plot line in such novels as ''Crime and Punishment'' and ''The Brothers Karamazov.'' In the twentieth century [[Thomas Mann]] labored to grasp the calamity of the [[First World War]] in his philosophical novel ''[[The Magic Mountain]].'' [[Franz Kafka]], [[Jean Paul Sartre]], [[Albert Camus]], [[Samuel Beckett]], and other [[existentialism|existential]] writers explored in literature a world where tradition, faith, and moral certitude had collapsed, leaving a void. Existential writers preeminently addressed questions of the meaning of life through studying the pain, anomie, and psychological dislocation of their fictional protagonists. In Kafka's ''Metamorphosis,'' to take a well known example, an office functionary wakes up one morning to find himself transformed into a giant cockroach, a new fact he industriously labors to incorporate into his routine affairs. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The concept of life having a meaning has been both parodied and promulgated, usually indirectly, in [[popular culture]] as well. For example, at the end of ''Monty Python's The Meaning of Life,'' a character is handed an envelope wherein the meaning of life is spelled out: "Well, it's nothing very special. Uh, try to be nice to people, avoid eating fat, read a good book every now and then, get some walking in, and try to live together in peace and harmony with people of all creeds and nations." Such tongue-in-cheek representations of meaning are less common than film and television presentations that locate the meaning of life in the subjective experience of the individual. This popular post-modern notion generally enables the individual to discover meaning to suit his or her inclinations, marginalizing what are presumed to be dated values, while somewhat inconsistently incorporating the notion of the relativity of values into an absolute principle. | |

| − | + | ==Assessment== | |

| − | + | Probably the most universal teachings concerning the meaning of life, to be followed in virtually all [[religion]]s in spite of much diversity of their traditions and positions, are: 1) the ethic of reciprocity among fellow [[human]]s, the "[[Golden Rule]]," derived from an ultimate being, called [[God]], [[Allah]], [[Brahman]], ''Taiji'', or ''[[Tian]]''; and 2) the spiritual dimension of life including an [[afterlife]] or eternal life, based on the requirement not to indulge in the external and material aspect of life. Usually, the connection of the two is that the ethic of reciprocity is a preparation in this world for the elevation of spirituality and for afterlife. It is important to note that these two constitutive elements of any religious view of meaning are common to all religious and spiritual traditions, although [[Jainism]]'s ethical teachings may not be based on any ultimate divine being and the [[Confucianism|Confucianist]] theory of the continual existence of ancestors together with descendants may not consider afterlife in the sense of being the other world. These two universal elements of religions are acceptable also to religious [[literature]], the essentialist position in [[philosophy]], and in some way to some of the [[existentialism|existentialist]] position. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Science|Scientific]] theories can be used to support these two elements, depending upon whether one's perspective is religious or not. For example, the [[biology|biological]] function of survival and continuation can be used in support of the religious doctrine of eternal life, and modern [[physics]] can be considered not to preclude some spiritual dimension of the universe. Also, when science observes the reciprocity of orderly relatedness, rather than random development, in the [[universe]], it can support the ethic of reciprocity in the Golden Rule. Of course, if one's perspective is not religious, then science may not be considered to support religion. Recently, however, the use of science in support of religious claims has greatly increased, and it is evidenced by the publication of many books and articles on the relationship of science and religion. The importance of scientific investigations on the origin and nature of life, and of the universe in which we live, has been increasingly recognized, because the question on the meaning of life has been acknowledged to need more than religious answers, which, without scientific support, are feared to sound irrelevant and obsolete in the age of science and technology. Thus, religion is being forced to take into account the data and systematic answers provided by science. Conversely, the role of religion has become that of offering a meaningful explanation of possible solutions suggested by science. | |

| − | + | It is interesting to observe that [[humanism|humanists]], who usually deny the existence of God and of afterlife, believe that it is important for all humans to love and respect one another: "Humanists acknowledge human interdependence, the need for mutual respect and the kinship of all humanity."<ref>[http://www.humanists-london.org/What_is_Humanism.html Principles of Humanism] ''Humanist Association of London and Area''. Retrieved June 28, 2021.</ref> Also, much of secular literature, even without imposing preconceived values, describes the beauty of love and respect in the midst of hatred and chaos in human life. Also, even a common sense discussion on the meaning of life can argue for the existence of eternal life, for the notion of self-destruction at one's [[death]] would appear to make the meaning of life destroyed along with life itself. Thus, the two universal elements of religions seem not to be totally alien to us. | |

| − | + | [[Christianity|Christian]] [[theology|theologian]] Millard J. Erickson sees God's blessing for humans to be fruitful, multiply, and have dominion over the earth ([[Genesis]] 1:28) as "the purpose or reason for the creation of humankind."<ref>Millard J. Erickson, ''Introducing Christian Doctrine'', ed. L. Arnold Hustad, 2nd ed. (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academics, 2001, ISBN 978-0801049194), 166.</ref> This [[Bible|biblical]] account seems to refer to the [[ethics|ethical]] aspect of the meaning of life, which is the reciprocal relationship of love involving multiplied humanity and all creation centering on God, although, seen with secular eyes, it might be rather difficult to accept the ideal of such a God-given purpose or meaning of life based on simple observation of the world situation. | |

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | = | ||

| − | < | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | + | * Ayer, A.J. ''The Meaning of Life.'' Scribner, 1990. ISBN 978-0684191959 | |

| − | + | * Baggini, Julian. ''What's it all about?: philosophy and the meaning of life.'' Oxford; NY: Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 978-0195300086 | |

| − | + | * Dalai Lama. ''The Meaning of Life.'' Wisdom Publications; Revised edition, 2000. ISBN 978-0861711734 | |

| − | + | * Darwin, Charles. ''The Origin of Species.'' Signet Classics, 2003. ISBN 978-0451529060 | |

| − | * '' | + | * Davies, Paul. ''The Fifth Miracle: The Search for the Origin and Meaning of Life.'' Simon & Schuster, 2000. ISBN 978-0684863092 |

| − | * '' | + | * Dawkins, Richard. ''The Blind Watchmaker: Why the Evidence of Evolution Reveals a Universe Without Design.'' W.W. Norton; reissue edition, 1996. ISBN 978-0393315707 |

| − | *''The | + | * Eagleton, Terry. ''The Meaning of Life.'' Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0199210701 |

| − | + | * Erickson, Millard J. ''Introducing Christian Doctrine''. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academics, 2015. ISBN 978-0801049194 | |

| − | + | * Frankl, Viktor E. ''Man's Search For Meaning,'' 4th edition. Pocket Books, 1997. ISBN 978-0671023379 | |

| − | * Haisch, Bernard ''The God Theory: Universes, Zero-point Fields, and What's Behind It All'' | + | * Goodier, Alban. ''The Meaning of Life: The Catholic Answer.'' Sophia Institute Press, 2002. ISBN 978-1928832614 |

| − | + | * Haisch, Bernard. ''The God Theory: Universes, Zero-point Fields, and What's Behind It All.'' Red Wheel/Weiser, 2006. ISBN 978-1578633746 | |

| − | * | + | * Lewis, Louise. ''No Experts Needed: The Meaning of Life According to You!'' iUniverse, Inc., 2007. ISBN 978-0595429714 |

| − | + | * Lovatt, Stephen C. ''New Skins for Old Wine: Plato's Wisdom for Today's World.'' Universal Publishers, 2007. ISBN 978-1581129601 | |

| − | * | + | * McGrath, Alister. ''Dawkins' God: Genes, Memes, and the Meaning of Life''. Blackwell Publishing Limited, 2004. ISBN 978-1405125383 |

| − | + | * Merton, Thomas. ''Thoughts on the East.'' New YorkCity: New Directions Publishing, 1995. ISBN 978-0811212939 | |

| − | * | + | * Tu, Wei-Ming. ''Confucian Thought: Selfhood as Creative Transformation.'' Albany: State University of New York Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0887060069 |

| − | * | + | * Vernon, Mark. ''Science, Religion, and the Meaning of Life.'' Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. ISBN 978-0230013414 |

| − | * | + | * Walker, Martin G. ''LIFE! Why We Exist…. And What We Must Do to Survive.'' Dog Ear Publishing, 2006. ISBN 978-1598582437 |

| − | * | ||

| − | * | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | * [ | + | All links retrieved November 8, 2022. |

| − | * [ | + | * [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/life-meaning/ The Meaning of Life] ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. |

| − | + | * [https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/hide-and-seek/201803/what-is-the-meaning-life What is the Meaning of Life?] by Neel Burton, ''Psychology Today''. | |

| − | + | * [https://positivepsychology.com/meaning-of-life-positive-psychology/ What is the Meaning of Life According to Positive Psychology] by Courtney E. Ackerman, ''PositivePsychology.com''. | |

| − | *[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===General Philosophy Sources=== | |

| + | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]. | ||

| + | *[http://www.iep.utm.edu/ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]. | ||

| + | *[http://www.bu.edu/wcp/PaidArch.html Paideia Project Online]. | ||

| + | *[http://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg]. | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] | |

| − | [[Category:Philosophy | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{credits|Meaning_of_life|143160381|Meaning_of_life|166381310|Meaning_of_life|199362820}} |

Latest revision as of 02:49, 9 November 2022

The question of the meaning of life is perhaps the most fundamental "why?" in human existence. It relates to the purpose, use, value, and reason for individual existence and that of the universe.

This question has resulted in a wide range of competing answers and explanations, from scientific to philosophical and religious explanations, to explorations in literature. Science, while providing theories about the How and What of life, has been of limited value in answering questions of meaning—the Why of human existence. Philosophy and religion have been of greater relevance, as has literature. Diverse philosophical positions include essentialist, existentialist, skeptic, nihilist, pragmatist, humanist, and atheist. The essentialist position, which states that a purpose is given to our life, usually by a supreme being, closely resembles the viewpoint of the Abrahamic religions.

While philosophy approaches the question of meaning by reason and reflection, religions approach the question from the perspectives of revelation, enlightenment, and doctrine. Generally, religions have in common two most important teachings regarding the meaning of life: 1) the ethic of the reciprocity of love among fellow humans for the purpose of uniting with a Supreme Being, the provider of that ethic; and 2) spiritual formation towards an afterlife or eternal life as a continuation of physical life.

Scientific Approaches to the Meaning of Life

Science cannot possibly give a direct answer to the question of meaning. There are, strictly speaking, no scientific views on the meaning of biological life other than its observable biological function: to continue. Like a judge confronted with a conflict of interests, the honest scientist will always make the difference between his personal opinions or feelings and the extent to which science can support or undermine these beliefs. That extent is limited to the discovery of ways in which things (including human life) came into being and objectively given, observable laws and patterns that might hint at a certain origin and/or purpose forming the ground for possible meaning.

What is the origin of life?

The question "What is the origin of life?" is addressed in the sciences in the areas of cosmogeny (for the origins of the universe) and abiogenesis (for the origins of biological life). Both of these areas are quite hypothetical—cosmogeny, because no existing physical model can accurately describe the very early universe (the instant of the Big Bang), and abiogenesis, because the environment of the young earth is not known, and because the conditions and chemical processes that may have taken billions of years to produce life cannot (as of yet) be reproduced in a laboratory. It is therefore not surprising that scientists have been tempted to use available data both to support and to oppose the notion that there is a given purpose to the emergence of the cosmos.

What is the nature of life?

Toward answering "What is the nature of life (and of the universe in which we live)?," scientists have proposed various theories or worldviews over the centuries. They include, but are not limited to, the heliocentric view by Copernicus and Galileo, through the mechanistic clockwork universe of René Descartes and Isaac Newton, to Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity, to the quantum mechanics of Heisenberg and Schrödinger in an effort to understand the universe in which we live.

Near the end of the twentieth century, equipped with insights from the gene-centered view of evolution, biologists began to suggest that in so far as there may be a primary function to life, it is the survival of genes. In this approach, success isn't measured in terms of the survival of species, but one level deeper, in terms of the successful replication of genes over the eons, from one species to the next, and so on. Such positions do not and cannot address the issue of the presence or absence of a purposeful origin, hence meaning.

What is valuable in life?

Science may not be able to tell us what is most valuable in life in a philosophical sense, but some studies bear on related questions. Researchers in positive psychology study factors that lead to life satisfaction (and before them less rigorously in humanistic psychology), in social psychology factors that lead to infants thriving or failing to thrive, and in other areas of psychology questions of motivation, preference, and what people value. Economists have learned a great deal about what is valued in the marketplace; and sociologists examine value at a social level using theoretical constructs such as value theory, norms, anomie, etc.

What is the purpose of, or in, (one's) life?

Natural scientists look for the purpose of life within the structure and function of life itself. This question also falls upon social scientists to answer. They attempt to do so by studying and explaining the behaviors and interactions of human beings (and every other type of animal as well). Again, science is limited to the search for elements that promote the purpose of a specific life form (individuals and societies), but these findings can only be suggestive when it comes to the overall purpose and meaning.

Analysis of teleology based on science

Teleology is a philosophical and theological study of purpose in nature. Traditional philosophy and Christian theology in particular have always had a strong tendency to affirm teleological positions, based on observation and belief. Since David Hume’s skepticism and Immanuel Kant’s agnostic conclusions in the eighteenth century, the use of teleological considerations to prove the existence of a purpose, hence a purposeful creator of the universe, has been seriously challenged. Purpose-oriented thinking is a natural human tendency which Kant already acknowledged, but that does not make it legitimate as a scientific explanation of things. In other words, teleology can be accused of amounting to wishful thinking.

The alleged "debunking" of teleology in science received a fresh impetus from advances in biological knowledge such as the publication of Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species (i.e., natural selection). Best-selling author and evolutionary biologist Richard Dawkins puts forward his explanation based on such findings. Ironically, it is also science that has recently given a new impetus to teleological thinking by providing data strongly suggesting the impossibility of random development in the creation of the universe and the appearance of life (e.g., the "anthropic principle").

Philosophy of the Meaning of Life

While scientific approaches to the meaning of life aim to describe relevant empirical facts about human existence, philosophers are concerned about the relationship between ideas such as the proper interpretation of empirical data. Philosophers have considered such questions as: "Is the question 'What is the meaning of life?' a meaningful question?"; "What does it really mean?"; and "If there are no objective values, then is life meaningless?" Some philosophical disciplines have also aimed to develop an understanding of life that explains, regardless of how we came to be here, what we should do, now that we are here.

Since the question about life’s meaning inevitably leads to the question of a possible divine origin to life, philosophy and theology are inextricably linked on this issue. Whether the answer to the question about a divine creator is yes, no, or "not applicable," the question will come up. Nevertheless, philosophy and religion significantly differ in much of their approach to the question. Hence, they will be treated separately.

Essentialist views

Essentialist views generally start with the assumption that there is a common essence in human beings, human nature, and that this nature is the starting point for any evaluation of the meaning of life. In classic philosophy, from Plato's idealism to Descartes' rationalism, humans have been seen as rational beings or "rational animals." Conforming to that inborn quality is then seen as the aim of life.

Reason, in that context, also has a strong value-oriented and ethical connotation. Philosophers such as Socrates, Plato, Descartes, Spinoza, and many others had views about what sort of life is best (and hence most meaningful). Aristotle believed that the pursuit of happiness is the Highest Good, and that such is achievable through our uniquely human capacity to reason. The notion of the highest good as the rational aim in life can still be found in later thinkers like Kant. A strong ethical connotation can be found in the Ancient Stoics, while Epicureanism saw the meaning of life in the search for the highest pleasure or happiness.

All these views have in common the assumption that it is possible to discover, and then practice, whatever is seen as the highest good through rational insight, hence the term "philosophy"—the love of wisdom. With Plato, the wisdom to discover the true meaning of life is found in connection with the notion of the immortal soul that completes its course in earthly life once it liberates itself from the futile earthly goals. In this, Plato prefigures a theme that would be essential in Christianity, that of God-given eternal life, as well as the notion that the soul is good and the flesh evil or at least a hindrance to the fulfillment of one’s true goal. At the same time, the concept that one has to rise above deceptive appearances to reach a proper understanding of life’s meaning has links to Eastern and Far Eastern traditions.

In medieval and modern philosophy, the Platonic and Aristotelian views were incorporated in a worldview centered on the theistic concept of the Will of God as the determinant factor for the meaning of our life, which was then seen as achieving moral perfection in ways pleasing to God. Modern philosophy came to experience considerable struggle in its attempt to make this view compatible with the rational discourse of a philosophy free of any prejudice. With Kant, the given of a God and his will fell away as a possible rational certainty. Certainty concerning purpose and meaning were moved from God to the immediacy of consciousness and conscience, as epitomized in Kant’s teaching of the categorical imperative. This development would gradually lead to the later supremacy of an existentialist discussion of the meaning of life, since such a position starts with the self and its choices, rather than with a purpose given "from above."

The emphasis on meaning as destiny, rather than choice, would one more time flourish in the early nineteenth century’s German Idealism, notably in the philosophy of Hegel where the overall purpose of history is seen as the embodiment of the Absolute Spirit in human society.

Existentialist views

Existentialist views concerning the meaning of life are based on the idea that it is only personal choices and commitments that can give any meaning to life since, for an individual, life can only be his or her life, and not an abstractly given entity. By going this route, existentialist thinkers seek to avoid the trappings of dogmatism and pursue a more genuine route. That road, however, is inevitably filled with doubt and hesitation. With the refusal of committing oneself to an externally given ideal comes the limitation of certainty to that alone which one chooses.

Presenting essentialism and existentialism as strictly divided currents would undoubtedly amount to a caricature, hence such a distinction can only be seen as defining a general trend. It is very clear, however, that philosophical thought from the mid-nineteenth century on has been strongly marked by the influence of existentialism. At the same time, the motives of dread, loss, uncertainty, and anguish in the face of an existence that needs to be constructed “out of nothing” have become predominant. These developments also need to be studied in the context of modern and contemporary historical events leading to the World Wars.

A universal existential contact with the question of meaning is found in situations of extreme distress, where all expected goals and purposes are shattered, including one’s most cherished hopes and convictions. The individual is then left with the burning question whether there still remains an even more fundamental, self-transcending meaning to existence. In many instances, such existential crises have been the starting point for a qualitative transformation of one’s perceptions.

Søren Kierkegaard invented the term "leap of faith" and argued that life is full of absurdity and the individual must make his or her own values in an indifferent world. For Kierkegaard, an individual can have a meaningful life (or at least one free of despair) if the individual relates the self in an unconditional commitment despite the inherent vulnerability of doing so in the midst our doubt. Genuine meaning is thus possible once the individual reaches the third, or religious, stage of life. Kirkegaard’s sincere commitment, far remote from any ivory tower philosophy, brings him into close contact with religious-philosophical approaches in the Far East, such as that of Buddhism, where the attainment of true meaning in life is only possible when the individual passes through several stages before reaching enlightenment that is fulfillment in itself, without any guarantee given from the outside (such as the certainty of salvation).

Although not generally categorized as an existentialist philosopher, Arthur Schopenhauer offered his own bleak answer to "what is the meaning of life?" by determining one's visible life as the reflection of one's will and the Will (and thus life) as being an aimless, irrational, and painful drive. The essence of reality is thus seen by Schopenhauer as totally negative, the only promise of salvation, deliverance, or at least escape from suffering being found in world-denying existential attitudes such as aesthetic contemplation, sympathy for others, and asceticism.

Twentieth-century thinkers like Martin Heidegger and Jean-Paul Sartre are representative of a more extreme form of existentialism where the existential approach takes place within the framework of atheism, rather than Christianity. Gabriel Marcel, on the other hand, is an example of Christian existentialism. For Paul Tillich, the meaning of life is given by one’s inevitable pursuit of some ultimate concern, whether it takes on the traditional form of religion or not. Existentialism is thus an orientation of the mind that can be filled with the greatest variety of content, leading to vastly different conclusions.

Skeptical and nihilist views

Skepticism

Skepticism has always been a strong undercurrent in the history of thought, as uncertainty about meaning and purpose has always existed even in the context of the strongest commitment to a certain view. Skepticism can also be called an everyday existential reality for every human being, alongside whatever commitments or certainties there may be. To some, it takes on the role of doubt to be overcome or endured. To others, it leads to a negative conclusion concerning our possibility of making any credible claim about the meaning of our life.

Skepticism in philosophy has existed since antiquity where it formed several schools of thought in Greece and in Rome. Until recent times, however, overt skepticism has remained a minority position. With the collapse of traditional certainties, skepticism has become increasingly prominent in social and cultural life. Ironically, because of its very nature of denying the possibility of certain knowledge, it is not a position that has produced major thinkers, at least not in its pure form.

The philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein and logical positivism, as well as the whole tradition of analytical philosophy represent a particular form of skepticism in that they challenge the very meaningfulness of questions like "the meaning of life," questions that do not involve verifiable statements.

Nihilism

Whereas skepticism denies the possibility of certain knowledge and thus rejects any affirmative statement about the meaning of life, nihilism amounts to a flat denial of such meaning or value. Friedrich Nietzsche characterized nihilism as emptying the world and especially human existence of meaning, purpose, comprehensible truth, or essential value. The term nihilism itself comes from the Latin nihil, which means "nothing."

Nihilism thus explores the notion of existence without meaning. Though nihilism tends toward defeatism, one can find strength and reason for celebration in the varied and unique human relationships it explores. From a nihilist point of view, morals are valueless and only hold a place in society as false ideals created by various forces. The characteristic that distinguishes nihilism from other skeptical or relativist philosophies is that, rather than merely insisting that values are subjective or even unwarranted, nihilism declares that nothing is of value, as the name implies.

Pragmatist views

Pragmatic philosophers suggest that rather than a truth about life, we should seek a useful understanding of life. William James argued that truth could be made but not sought. Thus, the meaning of life is a belief about the purpose of life that does not contradict one's experience of a purposeful life. Roughly, this could be applied as: "The meaning of life is those purposes which cause you to value it." To a pragmatist, the meaning of life, your life, can be discovered only through experience.

Pragmatism is a school of philosophy which originated in the United States in the late 1800s. Pragmatism is characterized by the insistence on consequences, utility and practicality as vital components of truth. Pragmatism objects to the view that human concepts and intellect represent reality, and therefore stands in opposition to both formalist and rationalist schools of philosophy. Rather, pragmatism holds that it is only in the struggle of intelligent organisms with the surrounding environment that theories and data acquire significance. Pragmatism does not hold, however, that just anything that is useful or practical should be regarded as true, or anything that helps us to survive merely in the short-term; pragmatists argue that what should be taken as true is that which most contributes to the most human good over the longest course. In practice, this means that for pragmatists, theoretical claims should be tied to verification practices—i.e., that one should be able to make predictions and test them—and that ultimately the needs of humankind should guide the path of human inquiry.

Humanistic views

Human purpose is determined by humans, completely without supernatural influence. Nor does knowledge come from supernatural sources, it flows from human observation, experimentation, and rational analysis preferably utilizing the scientific method: the nature of the universe is what we discern it to be. As are ethical values, which are derived from human needs and interests as tested by experience.

Enlightened self-interest is at the core of humanism. The most significant thing in life is the human being, and by extension, the human race and the environment in which we live. The happiness of the individual is inextricably linked to the well-being of humanity as a whole, in part because we are social animals which find meaning in relationships, and because cultural progress benefits everybody who lives in that culture.

When the world improves, life in general improves, so, while the individual desires to live well and fully, humanists feel it is important to do so in a way that will enhance the well-being of all. While the evolution of the human species is still (for the most part) a function of nature, the evolution of humanity is in our hands and it is our responsibility to progress it toward its highest ideals. In the same way, humanism itself is evolving, because humanists recognize that values and ideals, and therefore the meaning of life, are subject to change as our understanding improves.

The doctrine of humanism is set forth in the "Humanist Manifesto" and "A Secular Humanist Declaration."

Atheistic views

Atheism in its strictest sense means the belief that no God or Supreme Being (of any type or number) exists, and by extension that neither the universe nor its inhabitants were created by such a Being. Because atheists reject supernatural explanations for the existence of life, lacking a deistic source, they commonly point to blind abiogenesis as the most likely source for the origin of life. As for the purpose of life, there is no one particular atheistic view. Some atheists argue that since there are no gods to tell us what to value, we are left to decide for ourselves. Other atheists argue that some sort of meaning can be intrinsic to life itself, so the existence or non-existence of God is irrelevant to the question (a version of Socrates’ Euthyphro dilemma). Some believe that life is nothing more than a byproduct of insensate natural forces and has no underlying meaning or grand purpose. Other atheists are indifferent towards the question, believing that talking about meaning without specifying "meaning to whom" is an incoherent or incomplete thought (this can also fit with the idea of choosing the meaning of life for oneself).

Religious Approaches to the Meaning of Life

The religious traditions of the world have offered their own doctrinal responses to the question about life’s meaning. These answers also remain independently as core statements based on the claim to be the product of revelation or enlightenment, rather than human reflection.

Abrahamic religions

Judaism

Judaism regards life as a precious gift from God; precious not only because it is a gift from God, but because, for humans, there is a uniqueness attached to that gift. Of all the creatures on Earth, humans are created in the image of God. Our lives are sacred and precious because we carry within us the divine image, and with it, unlimited potential.