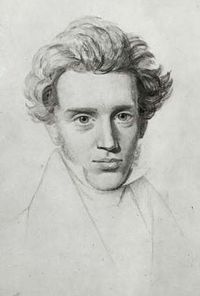

Søren Kierkegaard

| Western Philosophers 19th-century philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Name: Søren Aabye Kierkegaard | |

| Birth: May 5, 1813 (Copenhagen, Denmark) | |

| Death: November 11, 1855 (Copenhagen, Denmark) | |

| School/tradition: Continental philosophy,[1][2]Danish Golden Age Literary and Artistic Tradition, precursor to Existentialism, Postmodernism, Poststructuralism, Existential psychology, Neo-orthodoxy, and many more | |

| Main interests | |

| Religion, Metaphysics, Epistemology, Aesthetics, Ethics, Psychology | |

| Notable ideas | |

| Regarded as the father of Existentialism, angst, existential despair, Three spheres of human existence, knight of faith. | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Hegel, Abraham, Luther, Kant, Hamann, Lessing, Socrates[3] (through Plato, Xenophon, Aristophanes) | Jaspers, Wittgenstein, Heidegger, Sartre, Marcel, Buber, Bonhoeffer, Tillich, Barth, Auden, Camus, Kafka, de Beauvoir, May, Updike, Percy and many more |

Søren Aabye Kierkegaard (May 5, 1813 – November 11, 1855) was a nineteenth century Danish philosopher and theologian who has often been called “the father of existentialism.” Although his thought was influenced at least to some degree by the German philosopher G. W. F. Hegel, much of Kierkegaard’s work was devoted to critiquing Hegel, and in particular Hegel’s dialectical System which claimed Reason could contain all of reality. For Kierkegaard this reduced many religious truths to philosophy and so much of his critique was an attempt to show how certain experiences (particularly those concerning religious faith) escaped rational conceptualization. Moreover, Kierkegaard thought Hegel’s ethics absorbed the individual into the collective whole such that the individual person had no value outside of the social.

Kierkegaard’s work is marked by a unique complexity due to his anti-systematic and often literary approach to philosophy. His books were often attributed to pseudonyms and were written in an ironic style that was called “Socratic.” Kierkegaard’s early romance with Regine Olsen with whom he broke an engagement also had a profound influence on his life and writings. As a philosopher Kierkegaard is best known for such notions as his stages of existence, “faith in the absurd,” “truth as subjectivity,” and his analyses of existential anxiety and despair. Given the ambiguity of Kierkegaard’s style, however, the exact meaning of these notions continues to be debated. His overall existential philosophy had a tremendous influence on twentieth century thought, particularly in the areas of philosophy, theology, psychology, literature, and art.

Kierkegaard's historical role can be understood when we look at the fact that he and Ludwig Feuerbach brought forth a "breakdown" of Hegel's universal synthesis by critiquing it in two extremely different ways: through faith-oriented existentialism and atheistic anthropology, respectively, which eventually led to Barthian theology and Marxism. Kierkegaard's thought is a corrective to the rationalism of much of philosophy, reminding us of the inward dimension of existence, the experience of subjectivity.

Life

Early years (1813–1841)

Søren Kierkegaard was born to an affluent family in Copenhagen, the capital of Denmark. His father, Michael Pedersen Kierkegaard, was a very religious man who believed he had committed the unpardonable sin and as a result none of his children would live past the age of 34. Although it is not clear which sin his father had committed, possibilities include having cursed the name of God and having impregnated his future wife out of wedlock. Although many of his seven children did die young, the father’s predictions proved false when two of the children surpassed the age of 34. This early introduction to the notion of sin, however, along with the intimate bond he shared with his father (who often battled fits of melancholy) laid the foundation for much of Kierkegaard's later work (such as Fear and Trembling and The Concept of Anxiety).

Kierkegaard attended the School of Civic Virtue and Copenhagen University. At the university, Kierkegaard wrote his dissertation, The Concept of Irony, with Continual Reference to Socrates. The work was found by the university panel to be a noteworthy and well-thought out work, but a little too wordy and literary for a philosophical thesis. The practice of Socratic irony, along with his literary and wordy style, would remain significant and characteristic features throughout the entirety of Kierkegaard’s corpus. Kierkegaard graduated from the university in October of 1841.

Regine Olsen (1837–1841)

One of most important events in Kierkegaard's life (and a major influence on his work) was his relation with Regine Olsen (1822 - 1904). Kierkegaard met Regine in May of 1837 and the two instantly fell in love. In September of 1840, Kierkegaard formally proposed to Regine and she immediately accepted. Not long afterwards, however, Kierkegaard began to have second thoughts and less than a year after the proposal, he broke off the engagement. Over the years many theories have been offered to explain his reasons, but his precise motive for ending the engagement remains a mystery. Like his father, Kierkegaard suffered from melancholy and he seemed to believe he had inherited his father’s curse. For this reason, Kierkegaard judged himself to be unsuited for marriage. In any case, it is generally believed that Soren and Regine were deeply in love, and perhaps remained so even after she married Johan Frederik Schlegel, a prominent civil servant. Although for a period both Kierkegaard and Regine remained in Copenhagen their contact was limited to chance meetings on the streets. At one point, Kierkegaard asked Regine's husband for permission to speak with her, but the husband refused the request. Kierkegaard’s writings are filled with what appear to be subtle references intended to be directly or indirectly understood by Regine. Regine and her husband left the country when Schlegel was appointed Governor in the Danish West Indies. By the time Regine returned, Kierkegaard was dead. Regine Schlegel lived until 1904, and upon her death she was buried near Kierkegaard in the Assistens Cemetery in Copenhagen. One of the most poignant passages in Kierkegaard’s journals is the one which reads, “Had I had faith, I would have married Regine.”

The First Authorship (1841 – 1846)

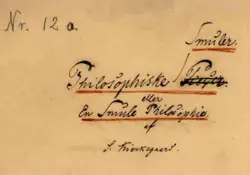

Kierkegaard's first important work was his university thesis, The Concept of Irony, which was presented in 1841. Shortly thereafter in 1943 he published the pseudonymous work, Either/Or which remains one of his most famous and important books. The work offers the beginning of Kierkegaard’s existential analysis in which he suggests that a fundamental choice must be made between an aesthetic or ethical existence.

In the same year that Either/Or appeared, Kierkegaard discovered that Regine was engaged. The news left a deep imprint on Kierkegaard and in turn his writings. In Fear and Trembling (1843) Kierkegaard seems to suggest that through a divine act, Regine might return to him. Several other works of this period, such as Repetition, allude to Kierkegaard’s relationship to his former fiancée.

The Corsair Affair (1845–1846)

In December of 1845, Peder Ludvig Møller published an article critiquing Kierkegaard’s work Stages on Life's Way. The article not only gave Stages a poor review, but showed little understanding of the style, substance, and intention of the pseudonymous work. Møller was also an editor of The Corsair, a Danish satirical paper that lampooned people of notable standing. Kierkegaard wrote two articles in response to both Møller’s original critique and to The Corsair itself. The former focused on the questionability of Møller's integrity while the latter launched a direct assault on The Corsair, in which Kierkegaard openly asked to be satirized.

Over the next few months, The Corsair took Kierkegaard up on his challenge to "be abused," and unleashed a series of attacks ridiculing Kierkegaard's appearance, voice, and habits. For months, Kierkegaard was harassed on the streets of Denmark so that schoolboys used to chide one another by saying, “Don’t be a Soren.” In an 1846 journal entry, Kierkegaard offers a long, detailed explanation of his attack on Møller and The Corsair, and also explains that this attack made him quit his indirect communication authorship. At that point Kierkegaard believed that his writing career had reached its conclusion; from then on, he decided, he would settle down into the quiet life of a Lutheran pastor.

The Second Authorship and the Attack Upon Christendom (1846–1855)

Not long afterwards Kierkegaard reversed his momentous decision. Rather than give up his authorship, he decided to redirect it. Whereas his first authorship offered a polemic against Hegel, his second authorship would launch an assault against the hypocrisy of Christendom. One should note that by 'Christendom' Kierkegaard did not mean Christianity itself, but rather the official Church which had become indistinguishable from Danish culture and society. After the Corsair incident, Kierkegaard emphasized the role of "the public" and the individual's interaction with it. His first work of this period was Two Ages: A Literary Review which was a critique of a well-known novel. While offering his critique of the work, Kierkegaard drew several insightful conclusions on the nature of the present age and its abstract and passionless attitude towards life.

The present age is essentially a sensible, reflecting age, devoid of passion, flaring up in superficial, short-lived enthusiasm and prudentially relaxing in indolence. … whereas a passionate age accelerates, raises up, and overthrows, elevates and debases, a reflective apathetic age does the opposite, it stifles and impedes, it levels.

Kierkegaard, The Present Age

As part of his analysis of the crowd, Kierkegaard realized the decay and decadence of the Christian church, especially the Church of Denmark. Kierkegaard believed Christendom had "lost its way" and so had abandoned the Christian faith. Christendom merely gave 'lip service' to the original and profound nature of the Christian doctrine taming it into a social and mundane doctrine of manners. Convinced that his duty was to inform others of the shallowness of this so-called Christian teaching of the Danish Church (which made everything too “easy”), Kierkegaard wrote several scathing criticisms on contemporary Christendom in works such as Christian Discourses, Works of Love, and Edifying Discourses in Diverse Spirits. His task throughout these works was to make things “more difficult,” though not more difficult than Christianity itself.

Kierkegaard's final years were taken up with a more sustained, outright attack on the Danish State Church by means of newspaper articles published in The Fatherland and a series of self-published pamphlets called The Moment. Kierkegaard was initially provoked by a speech made by Professor Hans Lassen Martensen, in which he referred to the recently deceased Bishop Mynster as an authentic "truth-witness." Although Kierkegaard had an affection towards Mynster, he believed Mynster’s conception of Christianity was in error and so served man's interest rather than God's. For this reason, it was an outrage to compare Mynster's life with that of a 'truth-witness'.

Before the tenth chapter of The Moment could be published, though, Kierkegaard collapsed on the street and was taken to a hospital. He stayed in the hospital for nearly a month and refused to receive communion from a priest of the church, whom Kierkegaard regarded as merely a state official rather than an authentic servant of God. Kierkegaad admitted to his friend since boyhood, Emil Boesen (who was himself a pastor and who kept a record of his conversations with Kierkegaard) that his (Kierkegaard’s) life, which looked like vanity to others, had been one of tremendous and unknown suffering. Kierkegaard died in Frederick's Hospital on November 11, 1855.

Indirect Communication and Pseudonymous Authorship

One of the most distinctive features of Kierkegaard’s large body of work is that a number of his books were published under pseudonyms. Although Kierkegaard was not immediately revealed to be the “real author,” the concealment of his identity from the reading public was not his primary motive. Rather by using a pseudonym Kierkegaard intentionally distanced himself from the works and the ideas contained in them. Similar to the way novelists will create characters who express ideas that they themselves do not embrace, Kierkegaard created philosophers who expressed ideas to which he himself did not necessarily commit. This technique allowed Kierkegaard to represent different ways of thinking and living which would connect to his different stages of existence. Moreover, this reflects Kierkegaard’s method of indirect communication where, as in poetry, the reader is required to interpret the possible meanings embedded in the text, rather than be told them straightforwardly or directly. In his The Point of View of my Work as an Author, Kierkegaard admitted that he wrote this way in order to prevent his works from being treated as a philosophical system with a systematic structure. He says, "In the pseudonymous works, there is not a single word which is mine. I have no opinion about these works except as a third person, no knowledge of their meaning, except as a reader, not the remotest private relation to them." Of course, given his continuous use of irony the reader is left to decide to what extent this “admission” should be taken seriously.

This indirect and ironic style of writing has made it difficult for scholars to demonstrate what precisely Kierkegaard’s definitive view on things were and where he ultimately stood in relation to the ideas presented in the pseudonymous texts. This ambiguity, however, was exactly what Kierkegaard was aiming at. His works constantly belittle the academic tendency to seek knowledge for knowledge’s sake as opposed to searching for a truth that would be worth living (and dying) for. For this reason, he hoped readers would read his works without attributing them to some aspect of his own life; rather readers should decide for themselves what value the ideas held and to what extent they agree or disagree with them. Furthermore, Kierkegaard in being opposed to Hegel was adamantly anti-systematic. He believed that existence itself was not a system, at least from the human perspective. Thus, Kierkegaard thought that his stages of existence: the aesthetic, ethical and religious, could be more truthfully approached “from the inside.” His pseudonyms authors, then, exist in the very ideas they are presenting.

The importance of recognizing the pseudonymous authorship has only recently been recognized in Kiekegaardian scholarship. Early Kierkegaardian scholars, such as Theodor W. Adorno, blatantly disregarded Kierkegaard's intentions and instead argued that the entire authorship should be treated as Kierkegaard's own personal and religious views. This way of looking at Kierkegaard's work leads to many confusions and seeming contradictions, and often makes Kierkegaard’s work appear to be incoherent. Most later scholars, however, have respected Kierkegaard's stated intentions and so interpret his work by attributing the pseudonymous texts to their respective authors. It is also important to note that while publishing these “aesthetic” works (which were attributed to a pseudonym) Kierkegaard almost always published concurrently a “religious” work or “edifying discourse” (which he published under his own name). Unfortunately, some scholars have not always appreciated the significance and connection between these two kinds of works. Some of Kierkegaard's most important pseudonyms include:

- Victor Eremita, editor of Either/Or

- Judge William, author of rebuttals to A in Either/Or

- Johannes de Silentio, author of Fear and Trembling

- Hilarius Bookbinder, editor of Stages on Life's Way

- Vigilius Haufniensis, author of The Concept of Dread

- Johannes Climacus, author of Philosophical Fragments and Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments

- Anti-Climacus, author of The Sickness Unto Death and Training in Christianity

Kierkegaard and Hegel

Kierkegaard’s relation to Hegel is complex. On the one hand, one of Kierkegaard's greatest philosophical contributions is his critique of Hegel. Kierkegaard objected vigorously to Hegel’s claim that his dialectical System could explain the whole of reality. For Hegel Christianity and religion are merely “moments” that can be rationally explained and so surpassed within a higher philosophical and conceptual system. Kierkegaard never tired of refuting (and ridiculing) these claims by showing that there are things in the world that cannot be explained by philosophy. Moreover, Kierkegaard feared that Hegel’s ethics would swallow the individual into the collective whole and so he argued that the Individual is higher than the Universal or the System. Faith, too, was something higher and so could not be grasped by an abstract philosophical theory, but only in the concrete and living practice of the individual or “knight of faith.”

Although Kierkegaard’s work offers a critique of Hegel, there is some of the 'Hegelian' in his work. Given the ambiguity of Kierkegaard’s style and his use of pseudonyms it is difficult for scholars to determine how much of Kierkegaard’s own dialectical style was intended as a parody of Hegel and how much was an authentic appropriation of it. Critics often accuse Kierkegaard of trying to disprove the dialectic by means of the dialectic, which would seem to be a ‘performative contradiction’. Defenders of Kierkegaard argue that he was not opposed to dialectic and reason but to the Hegelian claim that everything could be reconciled within it. While both Hegel and Kierkegaard were dialectical thinkers, they were very different in their understandings of the goal of dialectical thinking. For Hegel the goal is to reach a synthesis, while for Kierkegaard its purpose is only to open the door to inward subjectivity.

Main Themes in Kierkegaard's Thought

Existential Stages

Kierkegaard distinguishes between three levels or stages of individual existence through which one becomes an authentic self, namely, the aesthetic, the ethical, and the religious. He analyzes the different stages in rather cryptic form throughout many of his works, but makes them most explicit in Stages on Life's Way. Kierkegaard borrows the idea of stages from Hegel’s notion of sublation, though Kierkegaard interprets the notion in an existential rather than conceptual manner. In both, though, the higher stages include or incorporate the essential aspects of the lower one(s). For example, an ethical or religious person is still capable of aesthetic enjoyment, which is why Kierkegaard states that the religious does “not abolish the aesthetic, it merely dethrones it.” Moreover, it should be noted that the difference between these ways of existing are inward rather than outward, and so there is no necessary external evidence by which to prove which stage a person is actually existing in.

Aesthetic

Throughout his life Kierkegaard was devoted to art and aesthetics. Some of his pseudonyms refer to themselves as “religious poets,” and Kierkegaard himself, because of his passionate and ironic writing style and his use of pseudonyms, has often been called a "poet-philosopher." But although Kierkegaard appreciated the richness of beauty and aesthetic experience, much of his work was intended to show the meaninglessness and irresponsibility of a life lived solely on the aesthetic level. In short, an aesthetic life is one devoted to enjoyment, interest, and pleasure. Although Kierkegaard viewed the fine arts as the highest realization of aesthetic enjoyment, the artist as a person is not necessarily existing in this stage. Moreover, the aesthetic sphere also includes much baser forms of pleasure. For there are many degrees of aesthetic existence and perhaps at the bottom would be a life of gross consumerism. But even at the top, those lives which seek only the finest aesthetic refinements are self-absorbed and ultimately irresponsible since they view nothing higher than themselves to which they owe their allegiance. Kierkegaard thought that this way of living, far from being an anomaly, was how most people lived. That is, their lives and activities are guided by enjoyment, pleasure, and interest rather than any deep and meaningful commitment to something that transcended themselves and their own immediacy. For this reason, most people, whether they are aware of it or not, live lives of despair.

Ethical

The second level of existence is the ethical. Within the entirety and diversity of Kierkegaard’s authorship the ethical was discussed in various (and sometimes seemingly antithetic) ways. Judge William’s discussion of the ethical in Either-Or, for instance, stands in sharp contrast with Johannes de silentio’s analysis in Fear and Trembling. In general, though one might distinguish between two broad ways to understand the ethical within Kierkegaard’s work as a whole, depending upon whether one views the ethical in relation to the aesthetic or in relation to the religious.

The first way is the emphasis upon existential choice, a notion from which later twentieth century existential thinkers often borrowed. Here the ethical existence is defined by an individual making an authentic choice which commits her to a certain direction in life. In doing this, she enters the journey of self-becoming by adhering to values and ethical norms that transcend her own immediate wants or desires. At this ethical level her actions begin to take on a certain consistency and coherence which they lacked in the aesthetic sphere. For Judge William, the ethical is supremely important. For it calls each individual to take account of their own lives by scrutinizing their actions in terms of universal and absolute demands. These demands are to be appropriated by the individual in such a way that in making a genuine response the individual affirms herself as a truly committed and passionate consciousness. Any lesser response is an avoidance of responsibility and the universal nature of duty. Although the universality of these responsibilities seem to be self-evident, they are not to be followed simply as a matter of course. They must be done subjectively, that is, with a passion and understanding that views them as a having direct impact upon one’s own self-becoming. Ethics, then, is something one achieves for oneself with the realization that one’s entire self-understanding is involved. Thus, the meaning of one’s life amounts to whether one practices one’s conviction in an honest, passionate, and devoted way.

Another way in which some of Kierkegaard’s authors depict the ethical is by more or less equating it with the social norms of the particular group or culture. In this way it is the society which mediates the ethical and so the individual must adhere to those social values in order to be ethical. Although this view has often been appropriated by later thinkers in order to critique certain cultures (both past and present), Kierkegaard’s authors do not always take a negative view of it. For there is a legitimate ethical value in the individual sacrificing oneself for the good of others within the social whole. For in doing so, one transcends one’s own selfish or merely aesthetic wants. In Fear and Trembling, for instance, Silentio describes various ethical or “tragic heroes” such as Agamemnon. In the classic tale the king, after making an oath to the gods, sacrifices his daughter for the good of the people. What distinguishes these ethical heroes is precisely that they are understood by the people (which is why they are considered to be heroes). Silentio will contrast such heroes with the “knights of faith” (such as Abraham) precisely by their not being understood (or if they are, it is always in hindsight after their particular trial has been endured in solitude and misunderstanding).

Religious

As with the ethical, the religious sphere of existence is approached by Kierkegaard and his pseudonyms in various ways. Although the ethical and the religious are intimately connected, just how Kierkegaard viewed this relation has been a matter of dispute among scholars. For the different pseudonymous works depict the religious not only in different but seemingly incompatible ways. Both ethics and religion rest on the awareness of a higher reality that gives meaning to actions. In moving from the ethical to the religious, however, the question arises as to what extent reason and the ethical values which serve as the mediation to the universal are not only transcended, but also transgressed. This raises the issue of the relation between faith and reason and to what extent faith goes beyond reason and to what extent it goes against reason. Here Kierkegaard’s ironic, unsystematic, and pseudonymous style of writing leaves his reader with a number of ambiguities. Whereas living in the ethical sphere involves a commitment to some ethical universal norms, existing in the religious sphere involves an immediate and direct relation to the Eternal.

In Concluding Unscientific Postscript to the Philosophical Fragments Johannes Climacus distinguishes between two types within the religious stage: Religiousness A and Religiousness B. Religiousness A is symbolized by Socrates, whose passionate pursuit of the truth and individual conscience led him to a subjective appropriation of truth which conflicted with his society. Thus, Socrates transcended a merely ethical manner of existing by recognizing the beyond of the eternal and a willingness to die for it. Socrates’ faith, then, was a kind of secular faith which did not stop short at the ethical but surpassed it. Nonetheless, Socrates’ faith was incomplete in that it lacked a proper object which could fulfill the paradoxical nature of his existence. For the paradoxical aspect of human existence is that while being a finite and limited being in time the human seeks the infinite, unlimited, and eternal.

Only through Christianity or Religiousness B is the paradoxical nature of human existence fulfilled. It is fulfilled not by being explained and so understood through reason, but by being believed and so understood by faith. For in the person of Jesus the Eternal breaks into time so that God exists in time. The Incarnation, then, is the Absolute Paradox through which human beings find their salvation. Moreover, the realization that the individual is sinful and so is the source of untruth, can only be righted not by an intellectual assent to a rational God, but through an immediate relation to the Absolute Paradox. Only in time, through a subjective and passionate appropriation of Christian revelation (which from a scientific standpoint is an “objective uncertainty”) does one come into a direct relationship with the Absolute Paradox: that is God, the transcendent, coming into time in human form to redeem human beings. For Kierkegaard, the very notion of this occurring is scandalous to human reason; indeed, it must be, and if it is not then one does not truly understand the Incarnation or the meaning of human sinfulness. For Kierkegaard, the impulse towards an awareness of a transcendent power in the universe is what religion is. Although religion has a social and so ethical dimension, it begins with the individual and his or her awareness of sinfulness. Here Kierkegaard reflects Lutheran and Augustinian teachings in which the immediate relation to the Absolute (God) is founded upon grace alone.

Leap of Faith

In both the Postscript and Fear and Trembling Kierkegaard’s pseudonyms speak of faith as “a leap.” Thus, later scholars make much of his “leap of faith” and many of the more negative critiques argue that this notion advocates an irrationalism or fideism in which reason is rejected in favor of blind impulse. These critics points to the texts in which faith is referred to as an absurdity. More favorable readings, however, argue that the importance of the pseudonymous authorship should not be devalued. They also emphasize Kierkegaard’s anti-Hegelianism. For Hegel the dialectical stages were necessary unfolding of history and understanding; in contrast, Kierkegaard insists that the transitions within his stages of existence are not necessary but contingent. It is in this sense, then, that one might understand “leap.” That is, the progressive movement from one stage to the next requires something more than a natural transition. A certain gap or chasm needs to be crossed. It is in this way, as well, one might understand doubt or despair as those gaps which are crossed by the leap of faith.

The relation between ethics and the leap of faith continues to be debated among scholars. Some philosophers who read Fear and Trembling conclude that it supports divine command. The divine command theory is a metaethical theory which claims moral values are whatever is commanded by God. If a divine command from God transcends ethics, it would seem that at times God can command an unethical act (such as murder in the case of Abraham and his son Isaac). Any religious person must be prepared for the event of a divine command from God that would take precedence over all moral and rational obligations. In Fear and Trembling Silentio called this event the teleological suspension of the ethical. The ethical duty is not cancelled but merely suspended at a particular place and time according to God’s own command. Abraham, the knight of faith, chose to obey God’s command unconditionally, and was rewarded with the title of "Father of Faith." Abraham transcended ethics and leapt into faith not only because he was willing to slay his son, but also because he believed he would receive his son back. For God had also promised Abraham that through Isaac he would become the “Father of many generations.”

Subjectivity

Johannes Climacus wrote in the Postscript the following famous line: "Subjectivity is truth." This line has often been used as proof that Kierkegaard promoted an irrationalism. Defenders of Kierkegaard claim this is a misinterpretation since it both confuses Kierkegaard with the author of the work, Climacus, and it misunderstands what is meant by the term ‘subjectivity’. Existential subjectivity refers not merely to the feelings or emotions of the subject, but rather the way a subject relates to something in terms of his or her own existence. Subjectivity, then, must be understood in relation to objectivity.

Scientists, historians, and speculative philosophers study the objective world in order to discover the truth of nature, history, and universal being. In doing so, they try to discover various laws of nature, history, and universal being. Although these laws have a general validity to them, the question that obsessed Kierkegaard throughout most of his works is how the individual himself relates to the world in terms of his or her existence. Existential or subjective truth, then, is measured precisely by the depth or passion of this relation. For instance, one can learn that the capital of Rhode Island is Providence, or that the earth rotates around the sun. Both of these truths are objective, and yet neither concerns me precisely as an individual. For Kierkegaard all objective truths are aesthetic and so have significance under the category of the interesting. Any knowledge insofar as it is objective is merely interesting; but knowledge insofar as it concerns my very self is subjective or existential.

To illustrate this notion of subjective truth, let us take the theme of death, which Kierkegaard himself often addressed. To say “all men are mortal” is to state an objective truth about the nature of human beings as finite creatures. But to say, “one day I will die” is to appropriate the objective truth to my very self and so offer the possibility of acknowledging the truth in my own being. The relation, then, is one of interiority and so the degree to which one appropriates existential truth varies. In fact, for Kierkegaard to appropriate existential truths fully or completely requires an entire lifetime. So for Kierkegaard merely to recite ethical or religious formulas in no way suggests that a person has advanced beyond the aesthetic stage to a higher one. For what matters is the degree and depth to which the individual commits to certain values and truths and so embodies them. The transition through the existential stages, then, is what Kiekegaard called “becoming a self.” Kierkegaard’s philosophy is sometimes confused with the existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre. Sartre argues that the self or subject creates one’s own meaning and values, and so creates one’s self. In contrast, Kierkegaard argues that in the transition through the existential stages one becomes a self precisely by losing or sacrificing one’s self. In the move from the aesthetic to the ethical the self sacrifices personal wants for higher ideals and universal values. Likewise, in the transition from the ethical to the religious, one sacrifices mediated ideals for the immediate encounter with the Eternal in faith. In this way, one loses one’s self in order to regain it as a higher level.

Pathos

It is pathos or passion that advances the subject beyond the aesthetic sphere. The aesthete, lacks passion for he cares only about the interesting and pleasurable. Without pathos one cannot transcend into an ethical existence where one does not simply parrot ethical norms but commits to them in order to provide meaning and direction in one’s life. Likewise, it is pathos that drives one to seek some higher good beyond the social or universal values practiced by the culture and in turn seek a divine and eternal source. Here, through pathos one strives to surpass the mediation of the ethical in favor of an immediate and direct encounter with the eternal. The recognition of this pathos is the awareness of an infinite source or desire in the self, one that is not satisfied by finite mediations but seeks the infinite. This, then, is the religious pathos which Kierkegaard calls faith.

Anxiety

For Kierkegaard, existential dread or anxiety is the fear we experience in the face of freedom. Kierkegaard uses the example of a man standing on the edge of a cliff. When the man looks over the edge, he experiences a focused fear of falling, but at the same time, the man feels a terrifying impulse to hurl himself over the edge. That experience is the dread or anxiety we experience in recognizing our own freedom and the possibility of choosing the destiny of our existence. The recognition of this freedom triggers immense feelings of dread which Kierkegaard called our "dizziness of freedom."

In The Concept of Dread, Kierkegaard’s pseudonym Vigilius Haufniensis analyzes this dread further. He focuses on the dread experienced by the first man Adam and his choice to eat from the tree of knowledge. Prior to Adam partaking of the fruit, the concepts of good and evil did not yet exist. Adam, then, had no concept of good and evil, and so did not know that eating from the tree was "evil." He did know, however, that God commanded him not to eat from the tree. The dread Adam experienced originated from God's prohibition itself since the command implied that Adam was free and so could choose either to obey God or not. Once Adam ate from the tree, sin was born. Thus, dread precedes sin, and it is dread that leads Adam to sin. Dread, then, "is the presupposition for hereditary sin."

And yet, there is a sense in which dread is related more to our intrinsic freedom than to sin. For Kierkegaard’s pseudonym also mentions that dread is a way for humanity to be saved as well. Because anxiety increases our self-awareness of choice and personal responsibility, it brings us from a state of un-self-conscious immediacy to self-conscious reflection. An individual becomes truly aware of their potential through the experience of dread. So although dread may be a possibility for sin, it can also be a recognition or realization of the freedom of possibility and the attainment of an authentic self.

Despair

Is despair an excellence or a defect? Purely dialectically, it is both. The possibility of this sickness is man's superiority over the animal, for it indicates infinite sublimity that he is spirit. Consequently, to be able to despair is an infinite advantage, and yet to be in despair is not only the worst misfortune and misery—no, it is ruination.

Søren Kierkegaard, The Sickness Unto Death

In The Sickness Unto Death Kierkegaard’s pseudonym Anti-Climacus offers a complex definition of the self as a synthesis of the finite and the infinite, and the relation that relates to itself in relating to another. Some scholars argue that the style of the work is a parody of the Hegelian dialectical method where opposites merge into ever-higher syntheses. In any case, the work offers an analysis of the various forms of despair in which the self in seeking its own fulfillment continues to direct itself toward objects or possibilities which fail to succeed in this aim of overcoming despair. At times the self loses itself in its own finitude or limitations; at other times it loses itself in its infinitude and endless possibilities. The key for Kierkegaard is the balance which one strikes in actualizing the possibilities which are truly one’s own and so following the course of one’s own life laid out specifically for oneself. Later existential thinkers, such as Sartre and Heidegger, borrow this notion of authentic possibility. For Kirkegaard’s specifically religious view, however, the authentic possibility of overcoming the ultimate despair of death and our own human finitude is fulfilled only through faith. In this way, self-becoming realizes itself only through a relation to the Eternal.

Kierkegaard's Influence

Kierkegaard's works were not made widely available until several decades after his death. Not until Georg Brandes, an early Kierkegaardian Danish scholar fluent in both Danish and German, translated his work was Kierkegaard made known to the academic community in Europe. The dramatist Henrik Ibsen became interested in Kierkegaard, as well, and so popularized the works in Scandinavia. German translations appeared during the early 1900s, while the first English translations were not produced until 1938. Kierkegaard's fame as a philosopher grew tremendously in the 1930s, mostly in relation to the growing existentialist movement. He is called the father of existentialism.

Many twentieth-century philosophers, both theistic and atheistic, drew many concepts from Kierkegaard, particularly the notions of angst, despair, and the importance of individual choice and commitment. Philosophers and theologians who have been influenced by Kierkegaard include Karl Jaspers, Paul Tillich, Rudolf Karl Bultmann, Martin Buber, Gabriel Marcel, Miguel de Unamuno, Karl Barth, Hans Urs von Balthasar, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus, Simone de Beauvoir, and Ludwig Wittgenstein.

Kierkegaard also influenced other disciplines such as literature and psychology. Many literary writers were influenced by Kierkegaard’s insightful analyses of existential themes and situations, such as Walker Percy, David Lodge, and John Updike. Kierkegaard also had a profound influence on psychology and created the foundations of Christian psychology, existential psychology and therapy. Ludwig Binswanger, Victor Frankl, and Carl Rogers are well-known existential or humanistic psychologists. Rollo May, an American existential psychologist, based his work The Meaning of Anxiety on Kierkegaard's The Concept of Anxiety. Kierkegaard's sociological work Two Ages: The Age of Revolution and the Present Age provides an interesting critique of modernity. Kierkegaard is also an important figure in postmodern debates.

According to Paul Tillich,[4] the nineteenth century witnessed a "breakdown" of Hegel's universal synthesis into two different schools of thought which constituted two extremely opposite ways of reacting against it: Kierkegaard's God-centered existentialism and Feuerbach's God-denying anthropology. Tillich also notes that both reactions historically led to the theology of Karl Barth and the communism of Karl Marx, respectively. The breakdown of Hegel's universal synthesis had to occur, according to Tillich, because its original attempt to synthesize the faith tradition of Pietism and the humanistic tradition of Enlightenment was far from successful. If it is true, it can be said that Kierkegaard played an importantly insightful role of bringing humans to the domain of experiencing inwardness with God beyond Hegel's rather mechanistic universal system, although the scope of Kierkegaard' thought may not look broad enough for some people.

Notes

- ↑ This classification is anachronistic; Kierkegaard was an exceptionally unique thinker and his works do not fit neatly into any one philosophical school or tradition, nor did he identify himself with any. However, his works are considered precursor to many schools of thought developed in the twentieth and twenty-fitst centuries. See "20th century receptions" in Cambridge Companion to Kierkegaard.

- ↑ Alastair Hannay and Gordon Marino, (eds). The Cambridge Companion to Kierkegaard. (Cambridge University Press 1997, ISBN 0521477190)

- ↑ The influence of Socrates can be seen in Kierkegaard's Sickness Unto Death and Works of Love.

- ↑ Paul Tillich. A History of Christian Thought. (Touchstone, 1972), 432-503.

Selected bibliography

Primary sources

- (1843) Either/Or, Edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton, 1987. ISBN 0691020426.

- (1843) Fear and Trembling, Translated by Alastair Hannay. Penguin, 1985. ISBN 0140444491.

- (1843) Repetition, Translated by Walter Lowrie. Princeton, 1946.

- (1844) Philosophical Fragments, Edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton, 1985. ISBN 0691020361.

- (1844) The Concept of Anxiety, Translated by Reidan Thompste and Albert B. Anderson. Princeton, 1981. ISBN 0691020116.

- (1845) Stages on Life's Way, Edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton, 1987. ISBN 0691020493.

- (1846) Concluding Unscientific Postscript to The Philosophical Fragments, Edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton, 1992. ISBN 0691020817.

- (1847) Upbuilding Discourses in Various Spirits, Edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton, 1993. ISBN 0691032742.

- (1847) Works of Love, Edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton, 1995. ISBN 0691037922.

- (1849) The Sickness Unto Death, Edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton, 1980. ISBN 0691020280.

- (1850) Training in Christianity, Edited and translated by Howard V. Hong and Edna H. Hong. Princeton, 1987. ISBN 0691020639.

Secondary sources

- Bellinger, Charles. The Genealogy of Violence: Reflections on Creation, Freedom, and Evil. Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0195134982

- Dru, Alexander. The Journals of Søren Kierkegaard. Oxford University Press, 1938.

- Duncan, Elmer. Søren Kierkegaard: Maker of the Modern Theological Mind. Word Books 1976, ISBN 0876804636

- Garff, Joakim. Søren Kierkegaard: A Biography. Princeton University Press 2005, ISBN 069109165X.

- Hannay, Alastair. Kierkegaard: A Biography. Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0521531810.

- Hannay, Alastair and Gordon Marino, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Kierkegaard. Cambridge University Press, 1997. ISBN 0521477190

- Kierkegaard, S. The Concept of Irony with Continual Reference to Socrates. Princeton University Press, 1989. ISBN 0691073546

- Lippit, John. Kierkegaard and Fear and Trembling. Routledge, 2003. ISBN 0415180473

- Oden, Thomas C. The Humor of Kierkegaard: An Anthology. Princeton University Press, 2004. ISBN 069102085X

- Ostenfeld, Ib, and Alastair McKinnon. Søren Kierkegaard's Psychology. Wilfrid Laurer University Press, 1972. ISBN 0889200688

- Tillich, Paul. A History of Christian Thought. Touchstone, 1972.

- Westphal, Merold. Becoming a Self: A Reading of Kierkegaard's Concluding Unscientific Postscript. Purdue University Press, 1996. ISBN 1557530904

External links

All links retrieved February 26, 2023.

- D. Anthony Storm's Commentary On Kierkegaard.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy - Søren Kierkegaard.

- Manuscripts from the Søren Kierkegaard Archive at Denmark's Royal Library.

- The Howard and Edna Hong Kierkegaard Library

- Online Kierkegaard Links.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.