Pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical movement that originated with Charles Sanders Peirce (1839 ‚Äď 1914) (who first stated the pragmatic maxim) and came to fruition in the early twentieth-century philosophies of William James and John Dewey. Most of the thinkers who describe themselves as pragmatists consider practical consequences or real effects to be vital components of philosophy. These thinkers found the value of philosophy to be its application in diverse disciplinary fields, and refused to separate the components of philosophy from practical concerns. Peirce conceived of pragmatism, not as a doctrine, but as a methodology to clarify the meaning of concepts, and contributed primarily to semantics. James developed pragmatism particularly as a theory of truth, and Dewey further developed pragmatism as a theory of inquiry.

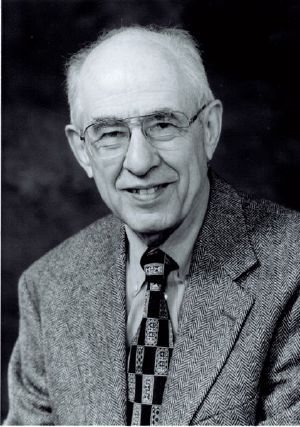

Upon the rise of analytic philosophy after World War II, the classical pragmatism represented by these philosophers became unpopular. Richard Rorty revitalized the pragmatist movement and developed it as "neopragmatism." With epistemology as its core, pragmatism contributed in diverse fields of study including psychology, pedagogy, and social theory, as well as metaphysics and ethics. The idea of the primacy of "practice" became a guiding thread for American culture.

Origins

Pragmatism originated as a philosophical movement in the United States in the late 1800s. Its main proponents were Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, and John Dewey (all members of The Metaphysical Club), as well as George Herbert Mead. William James was the first to use the term ‚Äúpragmatism‚ÄĚ in print, crediting Peirce with coining the term during the early 1870s. Peirce then began writing and lecturing to clarify his own interpretation of pragmatism, eventually coining another term, ‚Äúpragmaticism,‚ÄĚ for his original ideas (Menand 2001). Peirce sought to validate objective standards by evaluating what worked efficiently to realize some appropriate impersonal purpose; James‚Äô approach was a more subjective evaluation of what worked efficiently for a particular individual or group.

James and Pierce drew inspiration from Alexander Bain, who examined the crucial links among belief, conduct, and disposition and defined a ‚Äúbelief‚ÄĚ as a proposition on which a person is prepared to act. Other inspirations for the pragmatists include David Hume‚Äôs naturalistic account of knowledge and action; Thomas Reid‚Äôs direct realism; Georg Hegel‚Äôs introduction of temporality into philosophy; Francis Bacon, who coined the phrase "knowledge is power." Another influence was Kant‚Äôs stipulation of ‚Äúcontingent belief,‚ÄĚ suggesting that in the absence of absolute certainty, a plausible belief could serve as the basis for the accomplishment of certain actions; and Schopenhauer‚Äôs insistence that the intellect is subordinate to the will, and therefore reason is subordinate to action. These ideas were further developed by several German neo-Kantians, including Hans Vaihinger and Georg Simmel.

Historically, the roots of pragmatism can be traced as far back as the Academic Sceptics of ancient Greece, who denied the possibility of achieving genuine knowledge (episteme) of the real truth and suggested the substitution of plausible information (to pithanon) to satisfy the needs of practice. Utilitarianism’s model of judging the rightness of an action by the extent to which it accomplished the greatest good for the greatest number of people was a precursor of the pragmatist contention that an empirical claim is correct if its acceptance results in the maximum benefit.

Development

C.S. Pierce understood pragmatism, not as a philosophical doctrine, but a method by which we can clarify the meaning of concepts. He tried to define the meaning of philosophical concepts by their practical effects and eliminate pseudo-problems in philosophy. Pierce primarily developed pragmatism in the sphere of semantics. He also held Duns Scotus' realist ontology in high esteem. For Pierce, pragmatism was a methodology for developing a kind of realist metaphysics.

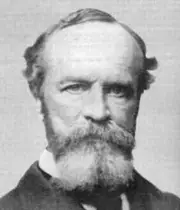

William James was a psychologist, and developed pragmatism from a semantic theory into a theory of truth. All the conceptual distinctions we make, James argued, appear as distinctions in practice. Pragmatism examines the truthfulness of ideas, not from the perspective of rational coherence and internal consistency, but from the practical consequences resulting from these ideas. James rejected the concept of truth as some sort of transcendent reality, arguing that truth is not some permanent entity which we discover, but is "creation" or "invention" which emerges during the process of experiences.

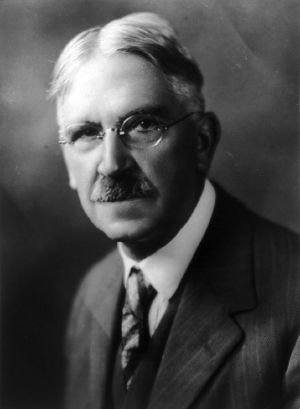

John Dewey conceived of pragmatism as a theory of inquiry. Dewey studied Hegel in his early stages, but received influences from James. Dewey dismissed traditional conceptual divisions such as subject-object, fact-value, theory-practice, and attempted to see the entire philosophical activity from the perspective of practice. He conceived of ideas and philosophical discourse as practical instruments for solving problems.

In post-World War II America, the classical pragmatism developed by Peirce, James, and Dewey became unpopular as the prominence of analytic philosophy increased. Richard Rorty presented Neo-pragmatism and revitalized the pragmatic movement, interpreting Heidegger, Wittgenstein, Derrida, Michel Foucault and others as pragmatists.

Pragmatist Epistemology

Pragmatist epistemology can be characterized by a broad emphasis on the importance of practical consequences: how theoretical ideas actually affect human life in general and the life of inquiry in particular.

The epistemology of the early pragmatists was heavily influenced by Darwinian evolutionary thinking. James and Dewey sought to establish continuity from the development of the animal world to the development of human world. Schopenhauer had suggested biological idealism, pointing out that the beliefs which help an organism to succeed in life might differ wildly from what is actually true. Pragmatism challenged the assumption that knowledge and action are two separate spheres, and that there exists an absolute or transcendental truth beyond the sort of inquiry that organisms use to cope with life. Pragmatism regarded inquiry as simply a means by which organisms could understand their environment. Concepts such as ‚Äúreal‚ÄĚ and ‚Äútrue‚ÄĚ were seen simply as labels that are useful in inquiry and cannot be understood outside of that context. The concept that theories and propositions are valid only within the context of a particular organism‚Äôs existence is plainly psychologist, but also assumes the existence of a real external world which must be dealt with.

A tendency by philosophers to categorize all views as either ‚Äúidealist‚ÄĚ or ‚Äúrealist;‚ÄĚ together with public misunderstanding of William James' eloquent figures of speech, resulted in the widespread but incorrect characterization of pragmatism as a form of subjectivism or idealism. Many of James' best-turned phrases, such as "truth's cash value" (James 1907, p. 200) and "the true is only the expedient in our way of thinking" (James 1907, 222), were taken out of context and caricatured in contemporary literature as the representing the view that any idea that has practical utility is true.

William James wrote:

It is high time to urge the use of a little imagination in philosophy. The unwillingness of some of our critics to read any but the silliest of possible meanings into our statements is as discreditable to their imaginations as anything I know in recent philosophic history. Schiller says the true is that which 'works.' Thereupon he is treated as one who limits verification to the lowest material utilities. Dewey says truth is what gives 'satisfaction'! He is treated as one who believes in calling everything true which, if it were true, would be pleasant. (James 1907, 90)

In reality, James asserts, the theory is a great deal more subtle.

Pragmatists disagreed with the view that beliefs must represent reality to be true, and argued that beliefs are dispositions which qualify as true or false depending on how helpful they prove in inquiry and in action. Theories acquired meaning only in the struggle of intelligent organisms to deal with the surrounding environment, and only became true when they were successful in this struggle. Most pragmatists, however, did not hold that anything that is practical or useful, or helps in short-term survival, should necessarily be regarded as true. C.S. Peirce took the pragmatic theory to imply that theoretical claims should be tied to verification practices and should be subject to test. Peirce defined truth as the ultimate outcome (not at a real point in time) of inquiry by a (usually) scientific community of investigators. Dewey characterized truthfulness as a species of the good: to state that something is true means that it is trustworthy or reliable and will remain so in every conceivable situation.

Central Pragmatist Tenets

The Primacy of practice

Pragmatism approaches issues in terms of the action of an organism in its environment. The human ability to theorize is seen as an integral part of intelligent action (practice), not as a separate sphere of intellectual activity. Theories and distinctions are tools which assist an organism in understanding its environment. They are abstracted from direct experience and ultimately have to explain and give meaning to the phenomena that gave rise to them.

John Dewey noted that there is no question of theory versus practice but rather of intelligent practice versus uninformed, stupid practice. In a conversation with William Pepperell Montague, Dewey said that his ‚Äúeffort had not been to practicalize intelligence but to intellectualize practice.‚ÄĚ (Quoted in Eldridge 1998, 5)

Deconstruction of Concepts and Theories

The pragmatists looked at philosophies and belief systems as attempts to come to terms with existence, and considered it an error to assign validity to a philosophical concept outside of the context in which it had been framed. In The Quest For Certainty, Dewey criticized what he called the philosophical fallacy; philosophers often take categories (such as the ‚Äúmental‚ÄĚ and the ‚Äúphysical‚ÄĚ) for granted and, not realizing that they are merely nominal concepts, invented to help solve specific problems, get entangled in all sorts of metaphysical and conceptual confusions. He gave examples such as the "ultimate Being" of Hegelian philosophers, the belief in a "realm of value," and the idea that logic, because it abstracts away from concrete thought, has nothing to do at all with thinking.

Naturalism and Anti-Cartesianism

Pragmatists set out to reform philosophy and reconcile it with science. Idealist and realist philosophy both had a tendency to see human knowledge as something beyond the grasp of science, and resorted either to a phenomenology inspired by Kant or to vague theories about "correspondence" to reality. Pragmatists criticized phenomenology because of its inability to relate meaningfully to the world as we experience it, and theories of correspondence for representing correspondence as an unanalyzable fact. Pragmatism tried to accomplish a psychological and biological explanation of the relationship between knower and known.

Richard Rorty expanded on these arguments in Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature where he criticized the attempts by many philosophers of science to carve out a space for epistemology that is entirely unrelated to, and sometimes thought of as superior to, the empirical sciences.

Anti-skepticism and Fallibilism

Hilary Putnam suggested that the reconciliation of antiskepticism and fallibilism is the central claim of American pragmatism.

Peirce insisted that, contrary to Descartes' famous and influential method in Meditations on First Philosophy, doubt cannot be feigned or fabricated for the purpose of conducting philosophical inquiry. Doubt, like belief, requires justification; it naturally arises from a real confrontation with some specific 'situation' which unsettles our belief in a specific proposition. Inquiry is the rationally self-controlled process of attempting to return to a settled state of belief about the matter.

Fallibilism, a philosophical doctrine most often applied to the natural sciences, is closely associated with C. S. Peirce, who was an astronomer and mathematician. Peirce asserted that claims of scientific knowledge can only tentatively be held to be true, as there is always the possibility that some further discovery will alter them or prove them to be false. As the history of science has repeatedly demonstrated, scientific theories can only be maintained as having some possibility of being true, particularly at the level of theoretical physics.

‚ÄĚI used for myself to collect my (logical) ideas under the designation fallibilism; and indeed the first step towards finding out is to acknowledge that you do not satisfactorily know already; so that no blight can so surely arrest all intellectual growth as the blight of cocksureness.‚ÄĚ (C. S. Peirce, Collected Papers, vol. 1, sect. 1:13)

Pragmatism in Other Fields of Philosophy

While pragmatism started out simply as a criterion of meaning, it quickly expanded to become a complete epistemology with wide-ranging implications for the entire field of philosophy.

In the philosophy of science, instrumentalism is the view that concepts and theories are merely useful instruments whose worth is measured not by whether the concepts and theories somehow mirror reality, but by how effective they are in explaining and predicting phenomena. Instrumentalism does not state that truth doesn't matter, but is rather a specific solution to the question of what truth and falsity mean and how they function in science.

Logic

Later in his life, when Schiller's pragmatism had become the nearest of any of the classical pragmatists to an ordinary language philosophy, he attacked logic in his textbook, "Formal Logic." Schiller sought to undermine the very possibility of formal logic, by showing that words only had meaning when used in an actual context. Near the end of his life, Schiller himself summarized the criticism of his book, in an essay entitled "Are All Men Mortal?" The least famous of Schiller's main works was the constructive sequel to his destructive "Formal Logic," "Logic for Use," in which he attempted to construct a new logic covering the context of discovery and the hypothetico-deductive method.

While F.C.S. Schiller actually dismissed the possibility of formal logic, most pragmatists are simply critical of its pretension to ultimate validity, and instead regard logic as one logical set of tools among others. C.S. Peirce developed multiple methods for doing formal logic. Stephen Toulmin's The Uses of Argument, in essence an epistemological work, inspired scholars of informal logic and rhetoric.

Metaphysics and Radical Empiricism

James and Dewey were straightforward empirical thinkers; experience was the ultimate test of the efficiency of propositions, and experience was what propositions were intended to explain. They were dissatisfied with ordinary empiricism because in the tradition of Hume, empiricists had a tendency to think of experience as nothing more than individual sensations. The pragmatists believed that an attempt should be made to explain every aspect of an experience, including connections and meaning, instead of dismissing them and positing sense data as the ultimate reality. Radical empiricism (or ‚Äúimmediate empiricism‚ÄĚ in Dewey's words) assigned a place to meaning and value, instead of disregarding them as subjective additions to a mechanistic material reality.

William James gives an interesting example of this philosophical shortcoming:

[A young graduate] began by saying that he had always taken for granted that when you entered a philosophic classroom you had to open relations with a universe entirely distinct from the one you left behind you in the street. The two were supposed, he said, to have so little to do with each other, that you could not possibly occupy your mind with them at the same time. The world of concrete personal experiences to which the street belongs is multitudinous beyond imagination, tangled, muddy, painful and perplexed. The world to which your philosophy-professor introduces you is simple, clean and noble. The contradictions of real life are absent from it. […] In point of fact it is far less an account of this actual world than a clear addition built upon it […] It is no explanation of our concrete universe. (James 1907, 8-9)

F.C.S. Schiller's first book, Riddles of the Sphinx, was published before he became aware of the growing pragmatist movement taking place in America. In it, Schiller argues for a middle ground between materialism and absolute metaphysics. Schiller contends that the result of the split between these two explanatory schemes (comparable to what William James called ‚Äútough-minded empiricism‚ÄĚ and ‚Äútender-minded rationalism‚ÄĚ) is that mechanicistic naturalism cannot make sense of the "higher" aspects of our world (free will, consciousness, purpose, universals, and God), while abstract metaphysics cannot make sense of the "lower" aspects of our world (the imperfect, change, physicality). While Schiller is vague about the exact sort of middle ground he is trying to establish, he suggests metaphysics as a tool that can aid inquiry and is only valuable insofar as it actually helps in explanation.

In the second half of the twentieth century, Stephen Toulmin argued that the need to distinguish between reality and appearance only arises within an explanatory scheme and therefore that there is no point in asking what 'ultimate reality' consists of. More recently, a similar idea has been suggested by the postanalytical philosopher Daniel Dennett who argues that anyone who wants to understand the world has to adopt the intentional stance and acknowledge both the 'syntactical' aspects of reality (material world) and its emergent or 'semantic' properties (meaning and value).

Radical Empiricism gives interesting answers to questions about the limits of science, the nature of meaning and value, and the workability of reductionism. These questions feature prominently in current debates about the relationship between science and religion, where most pragmatists would disagree with the assumption that science degrades everything that is meaningful into 'merely' physical phenomena.

Philosophy of mind

Both John Dewey in Nature and Experience (1929) and half a century later Richard Rorty in his monumental Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1979) argued that much of the debate about the relation of the mind to the body is the result of conceptual confusions. They argue instead that there is no need to posit the mind or mindstuff as an ontological category. Pragmatists view mind and body as a coherent entity and reject Cartesian dualism.

Ethics

Pragmatism sees no fundamental difference between practical and theoretical reason, nor any ontological difference between facts and values. Both facts and values have cognitive content: facts are knowledge that should be believed, values are hypotheses about what is good in action. Pragmatist ethics is broadly humanist, recognizing no ultimate test of morality beyond what matters for human beings. Good values are those for which we have good reasons (the Good Reasons approach). Pragmatist ethical theory predates other philosophers who have stressed important similarities between values and facts such as Jerome Schneewind and John Searle.

William James’ essay, The Will to Believe, has often been misunderstood as a plea for relativism or irrationalism. James argued that ethics always involves a certain degree of trust or faith, and that we cannot always wait for adequate proof when making moral decisions.

Moral questions immediately present themselves as questions whose solution cannot wait for sensible proof. A moral question is a question not of what sensibly exists, but of what is good, or would be good if it did exist. […] A social organism of any sort whatever, large or small, is what it is because each member proceeds to his own duty with a trust that the other members will simultaneously do theirs. Wherever a desired result is achieved by the co-operation of many independent persons, its existence as a fact is a pure consequence of the precursive faith in one another of those immediately concerned. A government, an army, a commercial system, a ship, a college, an athletic team, all exist on this condition, without which not only is nothing achieved, but nothing is even attempted. (James 1896)

Of the classical pragmatists, John Dewey wrote most extensively about morality and democracy. (Edel 1993) In his classic article, the Three Independent Factors in Morals (Dewey 1930) Dewey tried to integrate the three basic perspectives on morality: the right, the virtuous and the good. He held that all three provide meaningful ways to think about moral questions and that the possibility of conflict between the three elements exists and cannot always be easily solved. (Anderson, SEP)

Dewey also criticized the dichotomy between ‚Äúmeans and ends,‚ÄĚ which he believed had degraded both everyday working life and education by conceiving of them as merely a means to an end. He stressed the need for meaningful labor and a conception of education, not as a preparation for life, but life itself.

Dewey was opposed to other philosophies of his time, notably the emotivism of Alfred Ayer. Dewey envisioned the possibility of ethics as an experimental discipline, and thought that values could be best characterized, not as feelings or imperatives, but as hypotheses about what actions will lead to satisfactory results, or what he termed consummatory experience. A further implication of this view is that ethics is a fallible undertaking, because people not always sure about what they want, or whether what they want would really satisfy them.

Aesthetics

John Dewey's Art and Experience, based on the William James lectures he delivered at Harvard, was an attempt to show the integrity of art, culture and everyday experience. (Field, IEP) Dewey believed that art should be a part of everyone's creative lives and not just the privilege of a select group of artists. He also emphasized that an audience was an integral part of the work of art and more than a passive recipient. Dewey's treatment of art was a move away from the Kantian transcendental approach to aesthetics, which emphasized the unique character of art and the disinterested nature of aesthetic appreciation.

Philosophy of religion

Both Dewey (A Common Faith) and James (The Varieties of Religious Experience) investigated the role of religion in contemporary society. William James held that something is true only insofar as it works. For example, the statement that ‚Äúprayer is heard‚ÄĚ may ‚Äúwork‚ÄĚ on a psychological level but will not actually help to bring about the things you pray for; it may be better to refer to the soothing effect of prayer than to claim that prayers are actually heard. Pragmatism did not dismiss religion, but did not defend religious faith beyond its manifestation in everyday life.

Analytical, Neoclassical and Neopragmatism

Neopragmatism refers to various thinkers, some of them radically opposed to each other, such as Richard Rorty and Hilary Putnam. The name is usually taken to mean that the thinkers in question significantly diverge from 'the big three' (Peirce, James, Dewey) either in their philosophical program (many of them are loyal to the analytic tradition) or in thought. Important analytical thinkers include C.I. Lewis, W.V.O. Quine, Donald Davidson, Hilary Putnam and the early work of Richard Rorty]]. Stanley Fish, the later Rorty and J√ľrgen Habermas are closer to continental philosophy.

Neoclassical pragmatism denotes those thinkers who stay closer to the project of the classical pragmatists, such as Sidney Hook and Susan Haack (known for the theory of foundherentism).

Not all pragmatists are easily characterized. Stephen Toulmin, whose thought coincides with that of the neoclassical pragmatists, arrived at his conclusions largely independently from either the classical or neoclassical tradition, by following the thought of Wittgenstein, and does not identify himself as a pragmatist.

Contemporary Influence

The twentieth century movements of logical positivism, behaviorism, functionalism and ordinary language philosophy all have similarities with pragmatism. Like pragmatism, logical positivism provides a verification criterion of meaning that is supposed to rid us of nonsense metaphysics. However, logical positivism does not emphasize action like pragmatism does. Furthermore, the pragmatists rarely used their maxim of meaning to rule out all metaphysics as nonsense. Usually, pragmatism was put forth to correct metaphysical doctrines, or to construct empirically verifiable ones, rather than to provide a wholesale rejection.

Ordinary language philosophy is closer to pragmatism than other philosophy of language because of its nominalist character and because it takes the broader functioning of language in an environment as its focus instead of investigating abstract relations between language and world.

Pragmatism has ties to process philosophy. Much of the work of pragmatist thinkers developed in dialogue with process philosophers like Henri Bergson and Alfred North Whitehead, who aren't usually considered pragmatists because they differ so much on other points. (Douglas Browning, et al. 1998; Rescher, SEP)

Criticism

Although many later pragmatists such as W.V.O. Quine were actually analytic philosophers, the most vehement criticisms of classical pragmatism came from within. Bertrand Russell was especially known for his vituperative attacks on what he thought was little more than epistemological relativism and short-sighted practicalism. Realists in general often could not fathom how pragmatists could seriously call themselves empirical or realist thinkers, and thought pragmatist epistemology was but a disguised manifestation of idealism. (Hildebrand 2003)

Edmund Husserl criticized psychologism, a critical aspect of pragmatist epistemology, in his The Prolegomena of Pure Logic. Gottlob Frege, an important founder of analytic philosophy, did the same in his The Foundations of Arithmetic. Their criticism was honest but not decisive: it remains to be seen if indeed "psychology, because of its naturalism, had to miss entirely the accomplishment, the radical and genuine problem, of the life of the spirit" as Husserl claimed in The Vienna Lecture. Pragmatists insist that the exact opposite is the case.

Pragmatism suffered another kind of neglect because of the immense popularity of analytic philosophy and its ahistorical attitude; after their deaths the classical pragmatists were either ignored, forgotten, or caricatured. This is especially the case with Schiller: secondary sources on the work of Schiller are extremely rare, as are his primary works. Some claim that Schiller’s extravagant rhetoric and defense of a crude and unsophisticated form of pragmatism did a disservice to pragmatism.

Neopragmatism in the vein of Richard Rorty has been criticized as relativistic both by neoclassical pragmatists such as Susan Haack (Haack 1997) and by many analytic philosophers (Dennett 1998). Rorty's early analytical work, however, differs notably from his later work which some, including Rorty himself, consider to be closer to literature criticism than to philosophy proper; most criticism is aimed at this latter phase of Rorty's thought.

A list of pragmatists

Classical pragmatists (1850-1950)

Important protopragmatists or related thinkers

Fringe figures

Neoclassical pragmatists (1950-)Neoclassical pragmatists stay closer to the project of the classical pragmatists than neopragmatists do.

|

Analytical, neo- and other pragmatists (1950-)(Often labelled neopragmatism as well.)

Other pragmatistsLegal pragmatists

Pragmatists in the extended sense

|

Bibliography

Important introductory primary texts

Note that this is an introductory list: some important works are left out and some less monumental works that are excellent introductions are included.

- C.S. Peirce, "How to Make Our Ideas Clear" (paper). Acadamedia, 2005. ISBN 978-0955073830

- C.S. Peirce, "A Definition of Pragmatism" (paper)

- William James, Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking (especially lectures I, II and VI). Waking Lion Press, 2007. ISBN 978-1600965364

- John Dewey, Reconstruction in Philosophy. Kessinger Publishing, 2006. ISBN 978-1428615144

- John Dewey, "Three Independent factors in Morals" (paper)

- W.V.O. Quine, "Three Dogmas of Empiricism" (paper)

Other sources

- Borradori, G. (Ed.) The American Philosopher: Conversations with Quine, Davidson, Putnam, Nozick, Danto, Rorty, Cavell, MacIntyre, Kuhn. Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1994. ISBN 978-0226066486

- Browning, Douglas and William T. Myers (Eds.) Philosophers of Process. New York : Fordham University Press, 1998. ISBN 058517105X

- Clarke, D. S. Rational Acceptance and Purpose. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 1988. ISBN 978-0847676002

- Dewey, John and Donald F. Koch (ed.) Lectures on Ethics 1900‚Äď1901. 1991.

- Dewey, John. The Quest for Certainty: A Study of the Relation of Knowledge and Action. New York: Minton, Balch. 1929.

- Dewey, John. Three Independent Factors in Morals. 1930.

- Eldridge, Michael. Transforming Experience: John Dewey's Cultural Instrumentalism. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 1998. ISBN 0585146845

- Flower, E. A History of Philosophy in America. Hackett Pub Co Inc, 1977. ISBN 978-0399116506

- Hildebrand, David L. Beyond Realism & Anti-Realism. 2003.

- Kuklick, B. A History of Philosophy in America: 1720-2000. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0199260164

- McDermid, D. The Varieties of Pragmatism: Truth, Realism, and Knowledge from James to Rorty. Continuum International Publishing Group, 2006. ISBN 978-0826487216

- Menand, Louis. The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2002. ISBN 978-0374528492

- Murphy, J. Pragmatism: From Peirce to Davidson. Westview Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0813378107

- Putnam, Hilary. Pragmatism: An Open Question. Blackwell Publishing, Incorporated, 2006. ISBN 978-0631193432

- Scheffler, I. Four Pragmatists: A Critical Introduction to Peirce, James, Mead, and Dewey. Humanities Press, 1974. ISBN 978-0391003514

- Shook, J. and Margolis, J. (Eds.) A Companion to Pragmatism. Oxford, Blackwell Publishing Limited, 2006. ISBN 978-1405116213

- Stuhr, J. (Ed.) Pragmatism and Classical American Philosophy: Essential Readings and Interpretive Essays. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0195118308

- Thayer, H.S. Meaning and Action: A Critical History of Pragmatism. Hackett Pub Co Inc, 1980. ISBN 978-0915144730

- Toulmin, Stephen. The Uses of Argument. Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0511062710

- West, C. The American Evasion of Philosophy: A Genealogy of Pragmatism. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1989. ISBN 978-0299119645

External links

All links retrieved November 30, 2022.

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy entries:

- Elizabeth Anderson. Dewey's Moral Philosophy.

- Robert Burch. Charles Sanders Peirce.

- N. Rescher. Process Philosophy.

- Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy entry:

- Richard Field. John Dewey (1859-1952).

- Peirce.org Charles S. Peirce Studies

- Pragmatism Cybrary

- W.V.O. Quine. "Two Dogmas of Empiricism". Philosophical Review. January 1951.

- William James. "Pragmatism, A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking, Popular Lectures on Philosophy". Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, 1907.

General Philosophy Sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- Paideia Project Online

- Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.