Difference between revisions of "Illusion" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→Definition) |

|||

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

Knowledge of illusions in the physical senses of taste, smell, and touch is limited. There exists very few examples of illusions perhaps due to the slower temporal resolution compared to that of vision and audio. | Knowledge of illusions in the physical senses of taste, smell, and touch is limited. There exists very few examples of illusions perhaps due to the slower temporal resolution compared to that of vision and audio. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | ===Examples=== | ||

| + | |||

| + | '''Phantom Limb''' - This tactile illusion is the sensation that an amputated body part, more commonly a limb, is still attached to the body. Most sensations are that of pain, but may include itching, warmth, cold, squeezing, and burning, although the limb may also feel as if it is shorter or in a distorted and painful position. Initially reasoned to be the product of inflamed nerve endings, Ramachandran verified that phantom limb sensations were due to the reorganization of the somatosensory cortex by showing that stroking different parts of the face led to perceptions of being touched on different parts of the missing limb (Ramachandran, Rogers-Ramachandran & Stewart 1992). | ||

==Cognitive approach== | ==Cognitive approach== | ||

Revision as of 03:04, 16 May 2007

An illusion is a distortion of a sensory perception, revealing how the brain normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. While illusions distort reality, they are generally shared by most people [1]. Illusions can occur with each of the human senses, but visual illusions are the most well known and understood. The emphasis on visual illusions occurs because vision often dominates the other senses. For example, individuals watching a ventriloquist will perceive the voice is coming from the dummy since they are able to see the dummy mouth the words[2]. Some illusions are based on general assumptions the brain makes during perception. These assumptions are made using organizational principles, like Gestalt, an individual's ability of depth perception and motion perception, and perceptual constancy. Other illusions occur because of biological sensory structures within the human body or conditions outside of the body within one’s physical environment.

Definition

Etymology: Middle English, from Anglo-French, from Late Latin illusion-, illusio, from Latin, action of mocking, from illudere to mock at, from in- + ludere to play, mock

The Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary defines "illusion" as:

- the state or fact of being intellectually deceived or misled; an instance of such deception

- a misleading image presented to the vision; something that deceives or misleads intellectually; perception of something objectively existing in such a way as to cause misinterpretation of its actual nature; a pattern capable of reversible perspective

Illusion are distortions of a sensory perception, revealing how the brain normally organizes and interprets sensory stimulation. While illusions distort reality, they are generally shared by most people [1]. Illusions can occur with each of the human senses, but visual illusions are the most well known and understood. The emphasis on visual illusions occurs because vision often dominates the other senses. Some illusions are based on general assumptions the brain makes during perception. These assumptions are made using organizational principles, such as an individual's depth perception and motion perception, and perceptual constancy. Other illusions occur because of biological sensory structures within the human body or conditions outside of the body within one’s physical environment. Understanding illusions therefore involves understanding the rules that govern perceptual construction and the context of the illusion.

Visual Illusions

Vision is one the physical senses that is continuously being engaged in daily life. Though the world is perceived as seamless, images and motions imperceptibly blending in the next, it is only so because of the continual, visual updates that the eyes relay to the brain on a time scale so rapid that a break in vision is never perceived. The collaboration of photo-receptors, ganglion cells, receptive fields, and the brain creates the perception of colors, seamless motion, contrast and quality such that the efficiency and completeness of vision is unparalleled in comparison with any piece of apparatus or instrumentation ever invented [5]. The existence of optical illusions underline the adaptations the brain has made in order to operate at the speed it does in perceiving and translating visual stimuli. Though "optical illusions" itself sounds pejorative, as if describing some malfunction, they actually reveal the various adaptations that are hard-wired into the brain. The study of the visual system often involves artificially manipulating visual stimuli specifically created to cause mis-perception of a visual scene.

Examples

Figure-Ground Illusion - Commonly known as the face/vase illusion, this illusion displays an aspect of perceptual organization, in which the brain is attempting to assign one shape as the figure on top of a background. There is considerable flexibility, as the brain can interpret the figure-ground illusion as a white chalice in front of a black background, and almost as simulataneously interpret the illusion as two, silhouetted faces facing each other over a white background. This illusion was made famous by Danish psychologist Edgar Rubin in 1915

Kanizsa Triangle - The Kanizsa triangle is a famous optical illusion that was first described by the Italian psychologist Gaetano Kanizsa in 1955. In this figure, a white, equilateral triangle seems to be obscuring three black circles and the outline of another equilateral triangle, though in fact none is drawn. This effect is known as a subjective or illusory contour and is a product of a process known as modal completion. Also the nonexistent white triangle appears to be brighter than the surrounding area, even though both the "triangle" and background are of the same brightness.

Ponzo Illusion - Illusions can be based on an individual's ability to see in three dimensions even through the image hitting the retina is only two dimensional. The Ponzo Illusion, revealed by Mario Ponzo in 1913, is an example of an illusion which uses monocular cues of depth perception to fool the eye. In the Ponzo illusion the converging parallel lines suggests to the brain that the image higher in the visual field is further away due to perspective. The brain therefore perceives it to be larger, though the two images hitting the retina are actually the same size.

Phi Phenomenon - In his Experimental Studies on the Seeing of Motion, Max Wertheimer described a perceptual illusion involving succession of still images that created the illusion of apparent motion. The classic phi phenomenon experiment involves two images projected in succession. The first image depicts a line on the left side of the frame. The second image depicts a line on the right side of the frame. The images may be shown in rapid succession, or each frame may be given several seconds of viewing time. At certain combinations of time and space between the two lines, observers will perceive the line moving from left to right. This illusion can be easily seen in blinking Christmas lights or the moving lights that border movie marquees.

Auditory Illusions

An auditory illusion involves another of the five tradidional senses, hearing. Hearing, as a sense, is achieved through sensitivity to the movement of molecules through a medium in the environment outside the organism. Individual species of organisms have sensitivities to frequencies that fall within a particular range. For example, humans are generally limited to frequencies between 20Hz to 20kHz, which are commonly called audio or sonic frequencies. While the physiology of hearing in vertebrates is not yet fully understood at this time, specifically sound transduction within the cochlea and the processing of sound by the brain itself, there are various illusions in which a listener may hear sounds that are not present in the stimulus, or "impossible" sounds. In short, audio illusions highlight areas where the human ear and brain, as organic, makeshift tools, differ from perfect audio receptors.

Examples

Octave Illusion - Discovered by Diana Deutsch in 1973, the octave illusion is an auditory illusion produced by playing an alternating sequence of two notes that are spaced an octave apart over headphones, such that when the right ear receives the high tone, the left ear receives the low tone, and vice versa. Many people perceive a single tone that switches in pitch and from ear to ear, hearing, for example, "high tone - silence - high tone - silence" in the right ear while hearing "silence - low tone - silence - low tone" in the left ear. Surprisingly, right-handed people also tend to hear the high tone in the right hear, while left-handers seem to show no tendencies.

McGurk Effect - This illusion is a perceptual phenomenon that shows the relation between hearing and seeing in speech perception, suggesting that speech perception relies on than one modality, and was first described by McGurk and McDonald in 1976. This effect may be experienced when a video of one phoneme's production is dubbed with a sound-recording of a different phoneme being spoken. Often, the perceived phoneme is a third, intermediate phoneme. For example, a visual /ga/ combined with a heard /ba/ is often heard as /da/. Further research has shown that it can exist throughout whole sentences. The effect is very robust; that is, knowledge about it seems to have little effect on one's perception of it. This is different from certain optical illusions, which break down once one 'sees through' them.

Gustatory, Olfactory, and Tactile Illusions

Knowledge of illusions in the physical senses of taste, smell, and touch is limited. There exists very few examples of illusions perhaps due to the slower temporal resolution compared to that of vision and audio.

Examples

Phantom Limb - This tactile illusion is the sensation that an amputated body part, more commonly a limb, is still attached to the body. Most sensations are that of pain, but may include itching, warmth, cold, squeezing, and burning, although the limb may also feel as if it is shorter or in a distorted and painful position. Initially reasoned to be the product of inflamed nerve endings, Ramachandran verified that phantom limb sensations were due to the reorganization of the somatosensory cortex by showing that stroking different parts of the face led to perceptions of being touched on different parts of the missing limb (Ramachandran, Rogers-Ramachandran & Stewart 1992).

Cognitive approach

Perceptual organization

In order to make sense of the world, the brain employs certain schemes that allow it to organize incoming sensations into meaninful information. Gestalt psychologists [3] believe one way this is done is by perceiving individual sensory stimuli as part of a meaningful whole (Gestalt means "whole" in German).

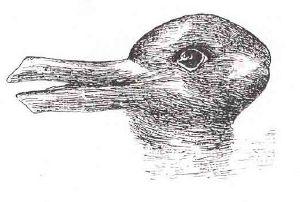

Gestalt laws of perceptual organization involve many factors that can be used to explain illusions including the Duck-Rabbit illusion (in which the image as a whole switches between that of a duck and that of a rabbit), the figure-ground illusion, in which the figure object and ground object are reversible.

Some of these Gestalt factors include grouping by similarity, grouping by proximity, good continuation, common fate, and closure. These principles work because the brain perceives regularities in the world. For example, portions of a single object tend to be close to one another (proximity), similar in color and texture (similarity), and move together (common fate). Gestalt psychologists argue that the brain has internalized these regularities over evolution and therefore account for perceptual distortions. The brain has a need to see familiar simple objects and has a tendency to created a "whole" image from individual elements [3]. For example, the illusory edges in the Kanizsa triangle are a result of of these regularities, which make it easier for the brain to perceive a bright, white triangle even though none exists. The use of perceptual organization to create meaning out of stimuli is the principle behind other well-known illusions including impossible objects and the Shepard tone, an auditory illusion.

Depth and motion perception

Illusions can be based on an individual's ability to see in three dimensions even through the image hitting the retina is only two dimensional. The Ponzo Illusion is an example of an illusion which uses monocular cues of depth perception to fool the eye.

In the Ponzo illusion the converging parallel lines tells the brain the image higher in the visual field is further away therefore the brain perceives the image to be larger, although the two images hitting the retina are the same size. The Optical illusion seen in a diorama/false perspective also exploits assumptions based on monocular cues of depth perception. The M. C. Escher painting Waterfall exploits rules of depth and proximity and our understand of the physical world to create an impossible illusion.

Like depth perception, motion perception is responsible for a number of sensory illusions. Film animation is based on the illusion that the brain perceives a series of slightly varied images produced in rapid succession as a moving picture. Likewise, when we are moving, as we would be while riding in a vehicle, stable surrounding objects may appear to move. We may also perceive a large object, like an airplane, to move more slowly, than smaller objects, like a car, although the larger object is actually moving at a faster rate. The Phi phenomenon is yet another example of how the brain perceives motion. The Phi phenomenon is an illusion created when adjacent lights are blinked on and off to create a sense of motion as in Christmas lighting or a neon sign. ????

Perceptual constancies

Perceptual constancies are sources of many illusions. Color constancy and brightness constancy are responsible for the fact that a familiar object will appear the same color regardless of the amount of light reflecting from it. An illusion of color difference can be created, however, when the luminosity of the area surrounding an unfamiliar object is changed. The color of the object will appear darker against a black field which reflects less light compared to a white field even though the object itself did not change in color. Like color, the brain has the ability to understand familiar objects as having a consistent shape or size. For example a door is perceived as rectangle regardless as to how the image may change on the retina as the door is opened and closed. Unfamiliar objects, however, do not always follow the rules of shape constancy and may change when the perspective is changed. The Shepard illusion of the changing table is an example of an illusion based on distortions in shape constancy.

Biological approach

Vision

The Hermann grid illusion and Mach bands are two illusions that are best explained using a biological approach. Lateral inhibition, where in the receptive field of the retina light and dark receptors compete with one another to become active, has been used to explain why we see bands of increased brightness at the edge of a color difference when viewing Mach bands. Once a receptor is active it inhibits adjacent receptors. This inhibition creates contrast, highlighting edges. In the Hermann grid illusion the grey spots appear at the intersection because of the inhibitory response which occurs as a result of the increased dark surround [4].

Lateral inhibition has also been used to explain the Hermann grid illusion, but this has recently been disproved

Other senses

Illusions can occur with the other senses including that of taste, smell and touch. It was discovered that even if some portion of the taste receptor on the tongue became damaged that illusory taste could be produced by tactile stimulation. Todrank, J & Bartoshuk, L.M., 1991. Evidence of Olfactory illusions occurred when positive or negative verbal labels were given prior to olfactory stimulation Herz R. S. & Von Clef J., 2001. Examples of Touch illusions include Phantom limb, the Thermal grill illusion, and the tactile illusion which occurs when the middle finger is crossed over the pointer finger and the fingers are ran along the bridge of the nose to the tip with one finger on each side of the nose . In this illusion two “noses” are felt at the tip. Interestingly, with Touch illusions similar brain sights are activated during illusory stimulation as actual stimulation Gross, L 2006 .

Disorders

Some illusions occur as result of an illness or a disorder. While these types of illusions are not shared with everyone they are typical of each condition. For example migraine suffers often report Fortification illusions….

Physical approach

- Mirages are optical distortions through the atmosphere that may be photographed. While the perceived reality (such as water in the desert) is illusory, the visual image (of a reflective surface) is real.

- Rainbows

- Antisolar rays

- Reflection

- Refraction

Paranormal activity and illusion

- Illusions as an explanation for paranormal activity, though this is debated.

- UFOs

- "hot hand" pattern recognition

- Loch Ness monster

Illusion in art and magic

- Stage magic is a popular form of entertainment based on illusion. Magicians use tricks to give their audiences the impression that seemingly impossible events have occurred. See magic (illusion).

- In fantasy works, actual magic may work by affecting the senses or producing an image, rather than producing a real change; this magic is frequently called illusion to distinguish it from more substantive forms of magic.

- Mimes are known for a repertoire of illusions that are created by physical means. The mime artist creates an illusion of acting upon or being acted upon an unseen object. These illusions exploit the audience's assumptions about the physical world. Well known examples include "walls, "climbing stairs," "leaning," "descending ladders," "pulling and pushing," et cetera. Amongst mimes, these illusions are sometimes referred to as pantomime

In psychiatry and philosophy the term illusion refers to a specific form of sensory distortion. Unlike a hallucination, which is a sensory experience in the absence of a stimulus, an illusion describes a misinterpretation of a true sensation so it is perceived in a distorted manner. For example, hearing voices regardless of the environment would be a hallucination, whereas hearing voices in the sound of running water (or other auditory source) would be an illusion.

Perhaps less common than visual illusions (or maybe more subtle) touch illusions also exist (Robles-De-La-Torre & Hayward 2001). These "illusory" tactile objects can be used to create "virtual objects" (see the MIT Technology Review article The Cutting Edge of Haptics).

Optical illusions

An optical illusion is always characterized by visually perceived images that, at least in common sense terms, are deceptive or misleading. Therefore, the information gathered by the eye is processed by the brain to give, on the face of it, a percept that does not tally with a physical measurement of the stimulus source. A conventional assumption is that there are physiological illusions that occur naturally and cognitive illusions that can be demonstrated by specific visual tricks that say something more basic about how human perceptual systems work.

Physiological illusions

Physiological illusions, such as the afterimages following bright lights or adapting stimuli of excessively longer alternating patterns (contingent perceptual aftereffect), are presumed to be the effects on the eyes or brain of excessive stimulation of a specific type - brightness, tilt, color, movement, and so on. The theory is that stimuli have individual dedicated neural paths in the early stages of visual processing, and that repetitive stimulation of only one or a few channels causes a physiological imbalance that alters perception.

File:Illusion movie.ogg Example movie which produces distortion illusion after you watch it and look away.

Cognitive illusions

Cognitive illusions are assumed to arise by interaction with assumptions about the world, leading to "unconscious inferences," an idea first suggested in the 19th century by Hermann Helmholtz. Cognitive illusions are commonly divided into ambiguous illusions, distorting illusions, paradox illusions, or fiction illusions.

(a). Ambiguous illusions are pictures or objects that elicit a perceptual 'switch' between the alternative interpretations. The Necker cube is a well known example; another instance is the Rubin vase.

(b). Distorting illusions are characterized by distortions of size, length, or curvature. A striking example is the Café wall illusion. Another example is the famous Mueller-Lyer illusion.

(c). Paradox illusions are generated by objects that are paradoxical or impossible, such as the Penrose triangle or impossible staircases seen, for example, in M. C. Escher's Ascending and Descending and Waterfall. The triangle is an illusion dependent on a cognitive misunderstanding that adjacent edges must join.

(d). Fictional illusions are defined as the perception of objects that are genuinely not there to all but a single observer, such as those induced by schizophrenia or a hallucinogen. These are more properly called hallucinations.

Well-known illusions

- Ames room illusion

- Autokinesis

- Barberpole illusion

- Benham's top

- Beta movement

- Bezold Effect

- Blivet (also known as the Impossible trident illusion)

- Cafe wall illusion

- Chubb illusion

- Color Phi phenomenon

- Cornsweet illusion

- Ebbinghaus illusion

- Ehrenstein illusion

- Fraser spiral illusion

- Grid illusion (also known as Hermann grid illusion)

- Hering illusion

- Hollow-Face illusion

- Impossible cube

- Jastrow illusion

- Kanizsa triangle

- Lilac chaser

- Mach bands

- Moon illusion

- Muller-Lyer illusion

- Necker cube

- Orbison illusion

- Penrose triangle aka Impossible triangle illusion

- Peripheral drift illusion

- Phi phenomenon

- Poggendorff illusion

- Ponzo illusion

- Rubin vase

- Same color illusion

- White's illusion

- Wundt illusion

- Zollner illusion

Many artists have worked with optical illusions, including M.C. Escher, Bridget Riley, Salvador Dalí, Giuseppe Arcimboldo, Marcel Duchamp, Oscar Reutersvärd, and Charles Allan Gilbert. Also some contemporary artists are experimenting with optical illusion, including: Dick Termes, Shigeo Fukuda, Patrick Hughes, István Orosz, Rob Gonsalves and Akiyoshi Kitaoka. Optical illusion is also used in film by the technique of forced perspective.

Some visual illusions such as the Ponzo illusion and the Vertical-horizontal illusions can also occur when using an auditory-to-vision sensory substitution device.

Auditory illusions

An auditory illusion is an illusion of hearing, the sound equivalent of an optical illusion: the listener hears either sounds which are not present in the stimulus, or "impossible" sounds. In short, audio illusions highlight areas where the human ear and brain, as organic, makeshift tools, differ from perfect audio receptors (for better or for worse).

Examples of auditory illusions:

- the Shepard tone or scale, and the Deutsch tritone paradox

- hearing a missing fundamental frequency, given other parts of the harmonic series

- Various psychoacoustic tricks of lossy Audio compression

- Octave illusion/Deutsch's High-Low Illusion

- Deutsch's scale illusion

- Glissando illusion

- Illusory continuity of tones

- McGurk Effect

Notes

- ↑ Solso, R. L. (2001). Cognitive psychology (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.ISBN 0-205-30937-2

- ↑ McGurk,H. & MacDonald, J.(1976). "Hearing lips and seeing voices," Nature 264, 746-748.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Myers, D. (2003). Psychology in Modules, (7th ed.) New York: Worth. ISBN 0-7167-5850-4

- ↑ Pinel, J. (2005) Biopsychology (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 0-205-42651-4

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Flanagan, J.R., Lederman, S.J. (2001). Neurobiology: Feeling bumps and holes, News and Views. Nature 412 (6845): 389–91.

- Hayward V, Astley OR, Cruz-Hernandez M, Grant D, Robles-De-La-Torre G (2004). Haptic interfaces and devices. Sensor Review 24 (1): 16–29.

- Robles-De-La-Torre G. & Hayward V. (2001). Force Can Overcome Object Geometry In the perception of Shape Through Active Touch. Nature 412 (6845): 445–8.

- Robles-De-La-Torre G. (2006). The Importance of the Sense of Touch in Virtual and Real Environments. IEEE Multimedia 13 (3, Special issue on Haptic User Interfaces for Multimedia Systems): 24–30.

- Eagleman, D.M. 2001. Visual Illusions and Neurobiology. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2(12): 920-6. (pdf)

- Gregory, Richard. 1997. Knowledge in perception and illusion. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 352:1121-1128 (pdf)

- Gregory, Richard. 2007. Illusion: The Phenomenal Brain. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192802852 ISBN 978-0192802859

- Purves D, Lotto B (2002) Why We See What We Do: An Empirical Theory of Vision. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

- Purves D, Lotto RB, Nundy S (2002) Why We See What We Do. American Scientist 90 (3): 236-242.

- Purves D, Williams MS, Nundy S, Lotto RB (2004) Perceiving the intensity of light. Psychological Rev. Vol. 111: 142-158.

- Renier, L., Laloyaux, C., Collignon, O., Tranduy, D., Vanlierde, A., Bruyer, R.,

De Volder, A.G. (2005). The Ponzo illusion using auditory substitution of vision in sighted and early blind subjects. Perception, 34, 857–867.

- Renier, L., Bruyer, R., & De Volder, A. G. (2006). Vertical-horizontal illusion

present for sighted but not early blind humans using auditory substitution of vision. Perception & Psychophysics, 68, 535–542.

- Robinson, J. O. 1998. The Psychology of Visual Illusion. Dover Publications. ISBN 0486404498 ISBN 978-0486404493

- Yang Z, Purves D (2003) A statistical explanation of visual space.Nature Neurosci 6: 632-640.

External links

- Illusion Works. A comprehensive website with illusions and explanation. Retrieved March 31, 2007.

- Ophtasurf. A complete website dealing with illusions with a lot of explanations.

- Paradoxical objects. An example of touch illusions of shape.

- The Cutting Edge of Haptics Using touch illusions to create virtual objects with sharp borders. An article in MIT's Technology review by Duncan Graham-Rowe.

- Magicians of Illusion

- Daily updated Optical Illusions Blog

- selection of the best optical illusions

- Fermüller, Cornelia. Theory of Optical Illusions Retrieved April 3, 2007.

- Optical Illusions: Computer Art in the Classroom

- Optical-Illusions-Project GH-School Hausen/Germany

- Explore, learn and have Fun with Optical Illusions

- Optical Illusions & Visual Phenomena

- Akiyoshi's illusion pages

- Project LITE Atlas of Visual Phenomena

- Collection of Optical Illusions

- Demonstrations of various auditory illusions at Kyushu Institute of Design

- Diana Deutsch's Web Page

- "You must be hearing things," CBC Radio's Quirks & Quarks for Kids

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.