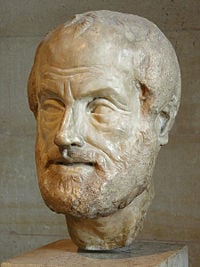

Aristotle

| Western philosophy Ancient philosophy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Name: Aristotle | |

| Birth: 384 B.C.E. | |

| Death: March 7 322 B.C.E. | |

| School/tradition: Inspired the Peripatetic school and tradition of Aristotelianism | |

| Main interests | |

| Politics, Metaphysics, Science, Logic, Ethics | |

| Notable ideas | |

| The Golden mean, Reason, Logic, Biology, Passion | |

| Influences | Influenced |

| Parmenides, Socrates, Plato | Alexander the Great, Al-Farabi, Avicenna, Averroes, Albertus Magnus, Copernicus, Galileo Galilei, Ptolemy, St. Thomas Aquinas, and most of Islamic philosophy, Christian philosophy, Western philosophy and Science in general |

Aristotle (Greek: Ἀριστοτέλης Aristotélēs) (384 B.C.E. – 322 B.C.E.) was a Greek philosopher, a student of Plato and teacher of Alexander the Great. He wrote on diverse subjects, including physics, metaphysics, poetry (including theater), logic, rhetoric, politics, government, ethics, biology and zoology. Along with Socrates and Plato, he was among the most influential of the ancient Greek philosophers, as they transformed Presocratic Greek philosophy into the foundations of Western philosophy as it is known today. Most researchers credit Plato and Aristotle with founding two of the most important schools of ancient philosophy, along with Stoicism and Epicureanism.

Aristotle's philosophy made a dramatic impact on both Western and Islamic philosophy. The beginning of 'modern' philosophy in the Western world is typically located at the transition from medieval, Aristotelian philosophy to mechanistic, Cartesian philosophy in the 16th and 17th centuries. Yet even the new philosophy continued to put debates in largely Aristotlean terms, or to wrestle with Aristotlean views. Today, there are avowed Aristotleans in many areas of contemporary philosophy, including ethics and metaphysics.

Life

Aristotle was born in Stageira, Chalcidice in 384 B.C.E. His father was Nicomachus, who became physician to King Amyntas of Macedon. At about the age of eighteen, he went to Athens to continue his education at Plato's Academy. Aristotle remained at the academy for nearly twenty years, not leaving until after Plato's death in 347 B.C.E. He then traveled with Xenocrates to the court of Hermias of Atarneus in Asia Minor. While in Asia, Aristotle traveled with Theophrastus to the island of Lesbos, where together they researched the botany and zoology of the island. Aristotle married Hermias' daughter (or niece) Pythias. She bore him a daughter, whom they named Pythias. Soon after Hermias' death, Aristotle was invited by Philip of Macedon to become tutor to Alexander the Great.

After spending several years tutoring the young Alexander, Aristotle returned to Athens. By 334 B.C.E., he established his own school there, known as the Lyceum. Aristotle conducted courses at the school for the next eleven years. While in Athens, his wife Pythias died, and Aristotle became involved with Herpyllis of Stageira, who bore him a son whom he named after his father, Nicomachus.

It is during this period that Aristotle is believed to have composed many of his works. Aristotle wrote many dialogues, only fragments of which survived. The works that have survived are in treatise form and were not, for the most part, intended for widespread publication, and are generally thought to be mere lecture aids for his students.

Aristotle not only studied almost every subject possible at the time, but made significant contributions to most of them. In physical science, Aristotle studied anatomy, astronomy, economics, embryology, geography, geology, meteorology, physics and zoology. In philosophy, he wrote on aesthetics, ethics, government, logic, metaphysics, politics, psychology, rhetoric and theology. He also studied education, foreign customs, literature and poetry. Because his discussions typically begin with a consideration of existing views, his combined works constitute a virtual encyclopedia of Greek knowledge.

Upon Alexander's death in 323 B.C.E., anti-Macedonian sentiment in Athens once again flared. Having never made a secret of his Macedonian roots, Aristotle fled the city to his mother's family estate in Chalcis, explaining, "I will not allow the Athenians to sin twice against philosophy."[1] However, he died there of natural causes within the year.

The loss of his works

Though Aristotle wrote many elegant treatises and dialogues (Cicero described his literary style as "a river of gold"),[2] the vast majority of his writings are now lost, while the literary character of those that remain is disputed. Aristotle's works were lost and rediscovered several times, and it is believed that only about one fifth of his original works have survived through the time of the Roman Empire.

After the Roman period, what remained of Aristotle's works were by and large lost to the West. They were preserved in the East by various Muslim scholars and philosophers, many of whom wrote extensive commentaries on his works. Aristotle lay at the foundation of the falsafa movement in Islamic philosophy, stimulating the thought of Al-Farabi, Ibn Sina, Ibn Rushd and others.

As the influence of the falsafa grew in the West, in part due to Gerard of Cremona's translations and the spread of Averroism, the demand for Aristotle's works grew. William of Moerbeke translated a number of them into Latin. When Thomas Aquinas wrote his theology, working from Moerbeke's translations, the demand for Aristotle's writings grew and the Greek manuscripts returned to the West, stimulating a revival of Aristotelianism in Europe.

Legacy

It is the opinion of many that Aristotle's system of thought remains the most marvellous and influential one ever put together by any single mind. According to historian Will Durant, no other philosopher has contributed so much to the enlightenment of the world.[3] He single-handedly began the systematic treatment of Logic, Biology and Psychology.

Aristotle is referred to as "The Philosopher" by Scholastic thinkers like Thomas Aquinas (for instance, Summa Theologica, Part I, Question 3). These thinkers blended Aristotelian philosophy with Christianity, bringing the thought of Ancient Greece into the Middle Ages. The medieval English poet Chaucer describes his student as being happy by having

At his bedded hed

Twenty books clothed in blake or red,

Of Aristotle and his philosophie;

The Italian poet Dante says of Aristotle in the first circles of hell,

I saw the Master there of those who know,

Amid the philosophic family,

By all admired, and by all reverenced;

There Plato too I saw, and Socrates,

Who stood beside him closer than the rest.

Dante, The Divine Comedy

Nearly all the major philosophers in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries felt impelled to address Aristotle's works. The French philosopher Descartes cast his philosophy (in the Meditations of 1641) in terms of moving away from the senses as a basis for a scientific understanding of the world. The great Jewish philosopher Spinoza argued in his Ethics directly against the Aristotlean method of understanding the operations of nature in terms of final causes. Leibniz often described his own philosophy as an attempt to bring together the insights of Plato and Aristotle. Kant adopted Aristotle's use of the form/matter distinction in describing the nature of representations - for instance, in describing space and time as 'forms' of intuition.

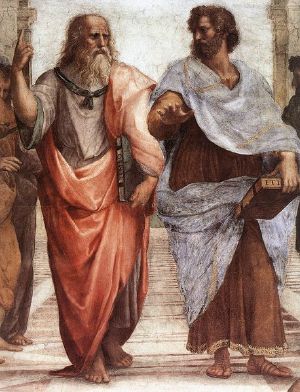

Methodology

Aristotle defines his philosophy as "the science of the universal essence of that which is actual." Plato had defined it as the "science of the idea," with the word "idea" referring to the unconditional basis of phenomena. Both student and master regard philosophy as universal; Aristotle, however, found the universal in particular things, which he called the essence of things, while Plato finds that the universal exists apart from particular things, and is related to them as their prototype or exemplar. For Aristotle, therefore, philosophic method implies the ascent from the study of particular phenomena to the knowledge of essences, while for Plato philosophic method means the descent from a knowledge of universal ideas to a contemplation of particular imitations of those ideas. In a certain sense, Aristotle's method is both inductive and deductive, while Plato's is essentially deductive from a priori principles.[4]

In Aristotle's terminology, "natural philosophy" is a branch of philosophy examining the phenomena of the natural world, and included fields that would be regarded today as physics, biology and other natural sciences. In modern times, the scope of philosophy has become limited to more generic or abstract inquiries, such as ethics and metaphysics, in which logic plays a major role. Today's philosophy tends to exclude empirical study of the natural world by means of the scientific method. In contrast, Aristotle's philosophical endeavors encompassed virtually all facets of intellectual inquiry.

In the larger sense of the word, Aristotle makes philosophy coextensive with reasoning, which he also would describe as "science." Note, however, that his use of the term science carries a different meaning than that covered by the term "scientific method." For Aristotle, "all science (dianoia) is either practical, poetical or theoretical." By practical science, he means ethics and politics; by poetical science, he means the study of poetry and the other fine arts; by theoretical science, he means physics, mathematics and metaphysics.

If logic, or, as Aristotle calls it, analytic, is regarded as a study preliminary to philosophy, the divisions of Aristotelian philosophy would consist of: (1) Logic; (2) Theoretical Philosophy, including Metaphysics, Physics, Mathematics, (3) Practical Philosophy and (4) Poetical Philosophy.

Epistemology

Logic

Aristotle's conception of logic was the dominant form of logic until 19th century advances in mathematical logic. Kant stated in the Critique of Pure Reason that Aristotle's theory of logic completely accounted for the core of deductive inference.

History

Aristotle "says that 'on the subject of reasoning' he 'had nothing else on an earlier date to speak of'".[5] However, Plato reports that syntax was devised before him, by Prodikos of Keos, who was concerned by the correct use of words. Logic seems to have emerged from dialectics; the earlier philosophers made frequent use of concepts like reductio ad absurdum in their discussions, but never truly understood the logical implications. Even Plato had difficulties with logic; although he had a reasonable conception of a deduction system, he was never could actually construct one, instead relying on his dialectic, which confused science with methodology.[6] Plato believed that deduction would simply follow from premises, hence he focused on maintaining solid premises so that the conclusion would logically follow. Subsequently, Plato realized that a method for obtaining conclusions would be most beneficial. He never succeeded in devising such a method, but his best attempt was published in his book Sophist, where he introduced his division method.[7]

Analytics and the Organon

What we today call Aristotelian logic, Aristotle himself would have labeled "analytics." The term "logic" he reserved to mean dialectics. Most of Aristotle's work is probably not in its original form, since it was most likely edited by students and later lecturers. The logical works of Aristotle were compiled into six books in about the early 1st century AD:

- Categories

- On Interpretation

- Prior Analytics

- Posterior Analytics

- Topics

- On Sophistical Refutations

The order of the books (or the teachings from which they are composed) is not certain, but this list was derived from analysis of Aristotle's writings. It goes from the basics, the analysis of simple terms in the Categories, to the study of more complex forms, namely, syllogisms (in the Analytics) and dialectics (in the Topics and Sophistical Refutations). There is one volume of Aristotle's concerning logic not found in the Organon, namely the fourth book of Metaphysics..[8]

Modal logic

Aristotle is also the creator of syllogisms with modalities (modal logic). The word modal refers to the word 'modes', explaining the fact that modal logic deals with the modes of truth. Aristotle introduced the qualification of 'necessary' and 'possible' premises. He constructed a logic which helped in the evaluation of truth but which was difficult to interpret.[9]

Physical Science

In the period between his two stays in Athens, between his times at the Academy and the Lyceum, Aristotle conducted most of the scientific thinking and research for which he is renowned today. In fact, most of Aristotle's life was devoted to the study of the objects of natural science. Aristotle’s metaphysics contains observations on the nature of numbers but he made no original contributions to mathematics. He did, however, perform original research in the natural sciences, e.g., botany, zoology, physics, astronomy, chemistry, meteorology, geometry and several other sciences.

Aristotle's writings on science are largely qualitative, as opposed to quantitative. Beginning in the sixteenth century, scientists began applying mathematics to the physical sciences, and Aristotle's work in this area was deemed hopelessly inadequate. His failings were largely due to the absence of concepts like mass, velocity, force and temperature. He had a conception of speed and temperature, but no quantitative understanding of them, which was partly due to the absence of basic experimental devices, like clocks and thermometers.

His writings provide an account of many scientific observations, but there are some curious errors. For example, in his History of Animals he claimed that human males have more teeth than females. In a similar vein, Galileo showed by simple experiments that Aristotle's theory that the heavier object falls faster than a lighter object is incorrect.

In places, Aristotle goes too far in deriving 'laws of the universe' from simple observation and over-stretched reason. Today's scientific method assumes that such thinking without sufficient facts is ineffective, and that discerning the validity of one's hypothesis requires far more rigorous experimentation than that which Aristotle used to support his laws.

Aristotle also had some scientific blind spots, the largest being his inability to see the application of mathematics to physics. Aristotle held that physics was about changing objects with a reality of their own, whereas mathematics was about unchanging objects without a reality of their own. In this philosophy, he could not imagine that there was a relationship between them. He also posited a flawed cosmology that we may discern in selections of the Metaphysics, which was widely accepted up until the 1500s. From the 3rd century to the 1500s, the dominant view held that the Earth was the center of the universe (geocentrism). This scientific concept, as proposed by Aristotle and Plato was later adopted as dogma by the Roman Catholic Church because it placed mankind at the center of the universe, and scientists who disagreed, such as Galileo, were considered heretics. This erroneous concept was eventually rejected.

Aristotle's scientific shortcomings should not mislead one into forgetting his great advances in the many scientific fields. For instance, he founded logic as a formal science and created foundations to biology that were not superseded (in the West) for two millennia. Moreover, he introduced the fundamental notion that nature is composed of things that change and that studying such changes can provide useful knowledge. This made the study of physics, and all other sciences, respectable. In actuality, however, this observation transcends physics into metaphysics.

Metaphysics

Aristotle defines metaphysics as "the knowledge of immaterial being," or of "being in the highest degree of abstraction." He refers to metaphysics as "first philosophy," as well as "the theologic science."

Causality

The material cause is that from which a thing comes into existence as from its parts, constituents, substratum or materials. This reduces the explanation of causes to the parts (factors, elements, constituents, ingredients) forming the whole (system, structure, compound, complex, composite, or combination), a relationship known as the part-whole causation. An example of a material cause would be the marble in a carved statue.

The formal cause tells us what a thing is, that any thing is determined by the definition, form, pattern, essence, whole, synthesis or archetype. It embraces the account of causes in terms of fundamental principles or general laws, as the whole (i.e., macrostructure) is the cause of its parts, a relationship known as the whole-part causation. An example of a formal cause might be the planning sketches of the carved statue.

The efficient cause is that from which the change or the ending of the change first starts. It identifies 'what makes of what is made and what causes change of what is changed' and so suggests all sorts of agents, nonliving or living, acting as the sources of change or movement or rest. Representing the current understanding of causality as the relation of cause and effect, this covers the modern definitions of "cause" as either the agent or agency or particular events or states of affairs. An example of an efficient cause might be the artist who carved the statue.

The final cause is that for the sake of which a thing exists or is done, including both purposeful and instrumental actions and activities. The final cause or telos is the purpose or end that something is supposed to serve, or it is that from which and that to which the change is. This also covers modern ideas of mental causation involving such psychological causes as volition, need, motivation, or motives, rational, irrational, ethical, all that gives purpose to behavior. The final cause of the artist might be the statue itself. (teleology)

Additionally, things can be causes of one another, causing each other reciprocally, as hard work causes fitness and vice versa, although not in the same way or function, the one is as the beginning of change, the other as the goal. (Thus Aristotle first suggested a reciprocal or circular causality as a relation of mutual dependence or influence of cause upon effect). Moreover, Aristotle indicated that the same thing can be the cause of contrary effects; its presence and absence may result in different outcomes.

Aristotle marked two modes of causation: proper (prior) causation and accidental (chance) causation. All causes, proper and incidental, can be spoken as potential or as actual, particular or generic. The same language refers to the effects of causes, so that generic effects assigned to generic causes, particular effects to particular causes, operating causes to actual effects. Essentially, causality does not suggest a temporal relation between the cause and the effect.

All further investigations of causality will consist of imposing the favorite hierarchies on the order causes, such as final > efficient> material > formal (Thomas Aquinas), or of restricting all causality to the material and efficient causes or to the efficient causality (deterministic or chance) or just to regular sequences and correlations of natural phenomena (the natural sciences describing how things happen instead of explaining the whys and wherefores).

Chance and spontaneity

Spontaneity and chance are causes of effects. Chance as an incidental cause lies in the realm of accidental things. It is "from what is spontaneous" (but note that what is spontaneous does not come from chance). For a better understanding of Aristotle's conception of "chance" it might be better to think of "coincidence": Something takes place by chance if a person sets out with the intent of having one thing take place, but with the result of another thing (not intended) taking place. For example: A person seeks donations. That person may find another person willing to donate a substantial sum. However, if the person seeking the donations met the person donating, not for the purpose of collecting donations, but for some other purpose, Aristotle would call the collecting of the donation by that particular donator a result of chance. It must be unusual that something happens by chance. In other words, if something happens all or most of the time, we cannot say that it is by chance.

However, chance can only apply to human beings, it is in the sphere of moral actions. According to Aristotle, chance must involve choice (and thus deliberation), and only humans are capable of deliberation and choice. "What is not capable of action cannot do anything by chance".[10]

Substance, potentiality and actuality

Aristotle examines the concept of substance (ousia) in his Metaphysics, Book VII and he concludes that a particular substance is a combination of both matter and form. As he proceeds to the book VIII, he concludes that the matter of the substance is the substratum or the stuff of which it is composed e.g. the matter of the house are the bricks, stones, timbers etc., or whatever constitutes the potential house. While the form of the substance, is the actual house, namely ‘covering for bodies and chattels’ or any other differentia (see also predicables). The formula that gives the components is the account of the matter, and the formula that gives the differentia is the account of the form.[11]

With regard to the change (kinesis) and its causes now, as he defines in his Physics and On Generation and Corruption 319b-320a, he distinguishes the coming to be from 1. growth and diminution, which is change in quantity 2. locomotion, which is change in space and 3. alteration, which is change in quality. The coming to be is a change where nothing persists of which the resultant is property. In that particular change he introduces the concept of potentiality (dynamis) and actuality (entelecheia) in association with the matter and the form.

Referring to potentiality, this is what a thing is capable of doing, or being acted upon, if it is not prevented by something else. For example, the seed of a plant in the soil is potentially (dynamei) plant, and if is not prevented by something, it will become a plant. Potentially beings can either 'act' (poiein) or 'be acted upon' (paschein), which can be either innate or learned. For example, the eyes possess the potentiality of sight (innate - being acted upon), while the capability of playing the flute can be possessed by learning (exercise - acting).

Actuality is the fulfillment of the end of the potentiality. Because the end (telos) is the principle of every change, and for the sake of the end exists potentiality, therefore actuality is the end. Referring then to our previous example, we could say that actuality is when the seed of the plant becomes a plant.

“ For that for the sake of which a thing is, is its principle, and the becoming is for the sake of the end; and the actuality is the end, and it is for the sake of this that the potentiality is acquired. For animals do not see in order that they may have sight, but they have sight that they may see.”[12]

In conclusion, the matter of the house is its potentiality and the form is its actuality. The formal cause (aitia) then of that change from potential to actual house, is the reason (logos) of the house builder and the final cause is the end, namely the house itself. Then Aristotle proceeds and concludes that the actuality is prior to potentiality in formula, in time and in substantiality.

With this definition of the particular substance (i.e., matter and form), Aristotle tries to solve the problem of the unity of the beings, e.g., what is that makes the man one? Since, according to Plato there are two Ideas: animal and biped, how then is man a unity? However, according to Aristotle, the potential being (matter) and the actual one (form) are one and the same thing.[13]

Universals and particulars

Aristotle's predecessor, Plato, argued that all things have a universal form, which could be either a property, or a relation to other things. When we look at an apple, for example, we see an apple, and we also analyze a form of an apple. In this distinction, there is a particular apple and a universal form of an apple. Moreover, we can place an apple next to a book, so that we can speak of both the book and apple as being next to each other.

Plato argued that there are some universal forms that are not a part of particular things. For example, it is possible that there is no particular good in existence, but "good" is still a proper universal form. Bertrand Russell is a contemporary philosopher that agreed with Plato on the existence of "uninstantiated universals."

Aristotle disagreed with Plato on this point, arguing that all universals are "instantiated." Aristotle argued that there are no universals that are unattached to existing things. According to Aristotle, if a universal exists, either as a particular or a relation, then there must have been, must be currently, or must be in the future, something on which the universal can be predicated. Consequently, according to Aristotle, if it is not the case that some universal can be predicated to an object that exists at some period of time, then it does not exist.

One way for contemporary philosophers to justify this position is by asserting the eleatic principle.

In addition, Aristotle disagreed with Plato about the location of universals. As Plato spoke of the world of the forms, a location where all universal forms subsist, Aristotle maintained that universals exist within each thing on which each universal is predicated. So, according to Aristotle, the form of apple exists within each apple, rather than in the world of the forms.

The five elements

- Fire, which is hot and dry.

- Earth, which is cold and dry.

- Air, which is hot and wet.

- Water, which is cold and wet.

- Aether, which is the divine substance that makes up the heavenly spheres and heavenly bodies (stars and planets).

Each of the four earthly elements has its natural place; the earth at the centre of the universe, then water, then air, then fire. When they are out of their natural place they have natural motion, requiring no external cause, which is towards that place; so bodies sink in water, air bubbles up, rain falls, flame rises in air. The heavenly element has perpetual circular motion.

Practical Philosophy

Ethics

Aristotle considered ethics to be a practical science, i.e., one mastered by doing rather than merely reasoning. Further, Aristotle believed that ethical knowledge is not certain knowledge (like metaphysics and epistemology) but is general knowledge. He wrote several treatises on ethics, including most notably, Nichomachean Ethics, in which he outlines what is commonly called virtue ethics.

Aristotle taught that virtue has to do with the proper function of a thing. An eye is only a good eye in so much as it can see, because the proper function of an eye is sight. Aristotle reasoned that man must have a function uncommon to anything else, and that this function must be an activity of the soul. Aristotle identified as the best activity of the soul as eudaimonia: a happiness or joy that pervades the good life. Aristotle taught that to achieve the good life, one must live a balanced life and avoid excess. This balance, he taught, varies among different persons and situations, and exists as a golden mean between two vices - one an excess and one a deficiency.

Politics

In addition to his works on ethics, which address the individual, Aristotle addressed the state in his work titled Politics. Aristole's conception of the state is very organic, and he is considered one of the first to conceive of the state in this manner.[14] Aristotle considered the state to be a natural community. Moreover, he considered the state to be prior to the family which in turn is prior to the individual. He is also famous for his statement that "man is by nature a political animal." Aristotle conceived of politics as being more like an organism, rather than a machine.

Biology and medicine

Aristotle believed that intellectual purposes, i.e., formal causes, guided all natural processes. Such a teleological view gave Aristotle cause to justify his observed data as an expression of formal design. Noting that "no animal has, at the same time, both tusks and horns," and "a single-hooved animal with two horns I have never seen," Aristotle suggested that Nature, giving no animal both horns and tusks, was staving off vanity, and giving creatures faculties only to such a degree as they are necessary. Noting that ruminants had a multiple stomachs and weak teeth, he supposed the first was to compensate for the latter, with Nature trying to preserve type of balance.[15]

In a similar fashion, Aristotle believed that creatures were arranged in a graded scale of perfection rising from plants on up to man, the scala naturae or Great Chain of Being.[16] . His system had eleven grades, arranged according "to the degree to which they are infected with potentiality," expressed in their form at birth. The highest animals laid warm and wet creatures alive, the lowest bore theirs cold, dry, and in thick eggs.

Aristotle also held that the level of a creature's perfection was reflected in its form, but not foreordained by that form.

He placed great importance on the type(s) of soul an organism possessed, asserting that plants possess a vegetative soul, responsible for reproduction and growth, animals a vegetative and a sensitive soul, responsible for mobility and sensation, and humans a vegetative, a sensitive, and a rational soul, capable of thought and reflection.[17]

Aristotle, in contrast to earlier philosophers, but in accordance with the Egyptians, placed the rational soul in the heart, rather than the brain.[18] Notable is Aristotle's division of sensation and thought, which generally went against previous philosophers, with the exception of Alcmaeon.[19]

Aristotle's successor at the Lyceum, Theophrastus, wrote a series of books on botany—the History of Plants—which survived as the most important contribution of antiquity to botany, even into the Middle Ages. Many of Theophrastus' names survive into modern times, such as carpos for fruit, and pericarpion for seed vessel.

Rather than focus on formal causes, as Aristotle did, Theophrastus suggested a mechanistic scheme, drawing analogies between natural and artificial processes, and relying on Aristotle's concept of the efficient cause. Theophrastus also recognized the role of sex in the reproduction of some higher plants, though this last discovery was lost in later ages.[20]

Bibliography

Note: Bekker numbers are often used to uniquely identify passages of Aristotle. They are identified below where available.

Major works

The extant works of Aristotle are broken down according to the five categories in the Corpus Aristotelicum. The titles are given in accordance with the standard set by the Revised Oxford Translation.[21] Not all of these works are considered genuine, but differ with respect to their connection to Aristotle, his associates and his views. Some, such as the Athenaion Politeia or the fragments of other politeia are regarded by most scholars as products of Aristotle's "school" and compiled under his direction or supervision. Other works, such as On Colours may have been products of Aristotle's successors at the Lyceum, e.g., Theophrastus and Straton. Still others acquired Aristotle's name through similarities in doctrine or content, such as the De Plantis, possibly by Nicolaus of Damascus. A final category, omitted here, includes medieval palmistries, astrological and magical texts whose connection to Aristotle is purely fanciful and self-promotional. Those that are seriously disputed are marked with an asterisk.

In several of the treatises, there are references to other works in the corpus. Based on such references, some scholars have suggested a possible chronological order for a number of Aristotle's writings. W.D. Ross, for instance, suggested the following broad arrangement (which of course leaves out much): Categories, Topics, Sophistici Elenchi, Analytics, Metaphysics Δ, the physical works, the Ethics, and the rest of the Metaphysics.[22] Many modern scholars, however, based simply on lack of evidence, are sceptical of such attempts to determine the chronological order of Aristotle's writings.[23]

Logical writings

- Organon (collected works on logic):

- (1a) Categories (or Categoriae)

- (16a) De Interpretatione (or On Interpretation)

- (24a) Prior Analytics (or Analytica Priora)

- (71a) Posterior Analytics (or Analytica Posteriora)

- (100b) Topics (or Topica)

- (164a) Sophistical Refutations (or De Sophisticis Elenchis)

Physical and scientific writings

- (184a) Physics (or Physica)

- (268a) On the Heavens (or De Caelo)

- (314a) On Generation and Corruption (or De Generatione et Corruptione)

- (338a) Meteorology (or Meteorologica)

- (391a) On the Universe (or De Mundo, or On the Cosmos) *

- (402a) On the Soul (or De Anima)

- (436a) Parva Naturalia (or Little Physical Treatises):

- Sense and Sensibilia (or De Sensu et Sensibilibus)

- On Memory (or De Memoria et Reminiscentia)

- On Sleep (or De Somno et Vigilia)

- On Dreams (or De Insomniis)

- On Divination in Sleep (or De Divinatione per Somnum)

- On Length and Shortness of Life (or De Longitudine et Brevitate Vitae)

- On Youth, Old Age, Life and Death, and Respiration (or De Juventute et Senectute, De Vita et Morte, De Respiratione)

- (481a) On Breath (or De Spiritu) *

- (486a) History of Animals (or Historia Animalium, or On the History of Animals, or Description of Animals)

- (639a) Parts of Animals (or De Partibus Animalium)

- (698a) Movement of Animals (or De Motu Animalium)

- (704a) Progression of Animals (or De Incessu Animalium)

- (715a) Generation of Animals (or De Generatione Animalium)

- (791a) On Colors (or De Coloribus) *

- (800a) On Things Heard (or De audibilibus) *

- (805a) Physiognomics (or Physiognomonica) *

- On Plants (or De Plantis) *

- (830a) On Marvellous Things Heard (or De mirabilibus auscultationibus) *

- (847a) Mechanics (or Mechanica or Mechanical Problems) *

- (859a) Problems (or Problemata)

- (968a) On Indivisible Lines (or De Lineis Insecabilibus) *

- (973a) The Situations and Names of Winds (or Ventorum Situs) *

- (974a) On Melissus, Xenophanes, and Gorgias (or MXG) * The section On Xenophanes starts at 977a13, the section On Gorgias starts at 979a11.

Metaphysical writings

- (980a) Metaphysics (or Metaphysica)

Ethical & Political writings

- (1094a) Nicomachean Ethics (or Ethica Nicomachea, or The Ethics)

- (1181a) Magna Moralia (or Great Ethics) *

- (1214a) Eudemian Ethics (or Ethica Eudemia)

- (1249a) On Virtues and Vices (or De Virtutibus et Vitiis Libellus, Libellus de virtutibus) *

- (1252a) Politics (or Politica)

- (1343a) Economics (or Oeconomica)

Aesthetic writings

- (1354a) Rhetoric (or Ars Rhetorica, or The Art of Rhetoric or Treatise on Rhetoric)

- Rhetoric to Alexander (or Rhetorica ad Alexandrum) *

- (1447a) Poetics (or Ars Poetica)

A work outside the Corpus Aristotelicum

- The Constitution of the Athenians (or Athenaion Politeia, or The Athenian Constitution)

Fragments

Dialogues

- On Philosophy (or On the Good)

- Eudemus (or On the Soul)

- Protrepticus

- On Justice

- On Good Birth

Specific editions

- Princeton University Press: The Complete Works of Aristotle: The Revised Oxford Translation (2 Volume Set; Bollingen Series, Vol. LXXI, No. 2), edited by Jonathan Barnes ISBN 0-691-09950-2 (the most complete recent translation of Aristotle's extant works, including a selection from the extant fragments)

- Oxford University Press: Clarendon Aristotle Series. Scholarly edition

- Harvard University Press: Loeb Classical Library (hardbound; publishes in Greek, with English translations on facing pages)

- Oxford Classical Texts (hardbound; Greek only)

Named after Aristotle

|

| ||||||

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Jones, W.T. (1980). The Classical Mind: A History of Western Philosophy. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 216. , cf. Vita Marciana 41.

- ↑ Cicero, Marcus Tullius (106B.C.E.-43B.C.E.). "flumen orationis aureum fundens Aristoteles". Academica. Retrieved 25-Jan-2007.

- ↑ Durant, Will (1926 (2006)). The Story of Philosophy. United States: Simon & Schuster, Inc., 92. ISBN 9780671739164.

- ↑ Jori, Alberto (2003). Aristotele. Milano: Bruno Mondadori Editore.

- ↑ Bocheński, I. M. (1951). Ancient Formal Logic. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

- ↑ Bocheński, 1951.

- ↑ Rose, Lynn E. (1968). Aristotle's Syllogistic. Springfield: Charles C Thomas Publisher.

- ↑ Bocheński, 1951.

- ↑ Rose, 1968.

- ↑ Aristotle, Physics 2.6

- ↑ Aristotle, Metaphysics VIII 1043a 10-30

- ↑ Aristotle, Metaphysics IX 1050a 5-10

- ↑ Aristotle, Metaphysics VIII 1045a-b

- ↑ Ebenstein, Alan and William Ebenstein (2002). Introduction to Political Thinkers. Wadsworth Group, 59.

- ↑ Mason, A History of the Sciences pp 43-44

- ↑ Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, pp 201-202; see also: Lovejoy, The Great Chain of Being

- ↑ Aristotle, De Anima II 3

- ↑ Mason, A History of the Sciences pp 45

- ↑ Guthrie, A History of Greek Philosophy Vol. 1 pp. 348

- ↑ Mayr, The Growth of Biological Thought, pp 90-91; Mason, A History of the Sciences, p 46

- ↑ The Complete Works of Aristotle, edited by Jonathan Barnes, 2 vols., Princeton University Press, 1984.

- ↑ W. D. Ross, Aristotle's Metaphysics (1953), vol. 1, p. lxxxii.

- ↑ E.g., Jonathan Barnes, "Life and Work" in The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle (1995), pp. 18-22.

Further reading

The secondary literature on Aristotle is vast. The following references are only a small selection.

- Ackrill J. L. 2001. Essays on Plato and Aristotle, Oxford University Press, USA

- Adler, Mortimer J. (1978). Aristotle for Everybody. New York: Macmillan. A popular exposition for the general reader.

- Bakalis Nikolaos. 2005. Handbook of Greek Philosophy: From Thales to the Stoics Analysis and Fragments, Trafford Publishing ISBN 1-4120-4843-5

- Barnes J. 1995. The Cambridge Companion to Aristotle, Cambridge University Press

- Bocheński, I. M. (1951). Ancient Formal Logic. Amsterdam: North-Holland Publishing Company.

- Bolotin, David (1998). An Approach to Aristotle’s Physics: With Particular Attention to the Role of His Manner of Writing. Albany: SUNY Press. A contribution to our understanding of how to read Aristotle's scientific works.

- Burnyeat, M. F. et al. 1979. Notes on Book Zeta of Aristotle's Metaphysics. Oxford: Sub-faculty of Philosophy

- Chappell, V. 1973. Aristotle's Conception of Matter, Journal of Philosophy 70: 679-696

- Code, Alan. 1995. Potentiality in Aristotle's Science and Metaphysics, Pacific Philosophical Quarterly 76

- Frede, Michael. 1987. Essays in Ancient Philosophy. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

- Gill, Mary Louise. 1989. Aristotle on Substance: The Paradox of Unity. Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Guthrie, W. K. C. (1981). A History of Greek Philosophy, Vol. 6. Cambridge University Press.

- Halper, Edward C. (2007) One and Many in Aristotle's Metaphysics, Volume 1: Books Alpha — Delta, Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-21-6

- Halper, Edward C. (2005) One and Many in Aristotle's Metaphysics, Volume 2: The Central Books, Parmenides Publishing, ISBN 978-1-930972-05-6

- Irwin, T. H. 1988. Aristotle's First Principles. Oxford: Clarendon Press

- Jori, Alberto. 2003. Aristotele, Milano: Bruno Mondadori Editore (Prize 2003 of the "International Academy of the History of Science") ISBN 88-424-9737-1

- Knight, Kelvin. 2007. Aristotelian Philosophy: Ethics and Politics from Aristotle to MacIntyre, Polity Press.

- Lewis, Frank A. 1991. Substance and Predication in Aristotle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lloyd, G. E. R. 1968. Aristotle: The Growth and Structure of his Thought. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., ISBN 0-521-09456-9.

- Lord, Carnes. 1984. Introduction to The Politics, by Aristotle. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Loux, Michael J. 1991. Primary Ousia: An Essay on Aristotle's Metaphysics Ζ and Η. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press

- Owen, G. E. L. 1965c. The Platonism of Aristotle, Proceedings of the British Academy 50 125-150. Reprinted in J. Barnes, M. Schofield, and R. R. K. Sorabji (eds.), Articles on Aristotle, Vol 1. Science. London: Duckworth (1975). 14-34

- Pangle, Lorraine Smith (2003). Aristotle and the Philosophy of Friendship. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Aristotle's conception of the deepest human relationship viewed in the light of the history of philosophic thought on friendship.

- Reeve, C. D. C. 2000. Substantial Knowledge: Aristotle's Metaphysics. Indianapolis: Hackett.

- Rose, Lynn E. (1968). Aristotle's Syllogistic. Springfield: Charles C Thomas Publisher.

- Ross, Sir David (1995). Aristotle, 6th ed., London: Routledge. An classic overview by one of Aristotle's most prominent English translators, in print since 1923.

- Scaltsas, T. 1994. Substances and Universals in Aristotle's Metaphysics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Strauss, Leo. "On Aristotle's Politics" (1964), in The City and Man, Chicago; Rand McNally.

- Taylor, Henry Osborn (1922). "Chapter 3: Aristotle's Biology", Greek Biology and Medicine.

- Veatch, Henry B. (1974). Aristotle: A Contemporary Appreciation. Bloomington: Indiana U. Press. For the general reader.

- Woods, M. J. 1991b. “Universals and Particular Forms in Aristotle's Metaphysics.” Oxford Studies in Ancient Philosophy supplement. 41-56

See also

- Aristotelianism

- Aristotelian view of God

- Aristotelian theory of gravity

- Philia

- Phronesis

- Potentiality and actuality (Aristotle)

- Aristotelian ethics

- Hylomorphism

External links

Template:Cleanup-spam

- Works by Aristotle. Project Gutenberg

- References for Aristotle

- Works by Aristotle at Perseus Project

- Some of Aristotles works: Analytica Priora & Posteriora, Poetics (All in Greek).

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy:

- "Biology" — by James Lennox.

- "Causality" — by Andrea Falcon.

- "Ethics" — by Richard Kraut.

- "Logic" — by Robin Smith.

- "Mathematics" — by Henry Mendell.

- "Metaphysics" — by S. Marc Cohen.

- "Philosophy of Nature" — Istvan Bodnar.

- "Political Theory" — by Fred Miller.

- "Psychology" — by Christopher Shields.

- "Rhetoric" — by Cristof Rapp.

- Aristotle OnLine Resources & Anthology of his works

- Catholic Encyclopedia: "Aristotle" — by William Turner.

- "Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy: Aristotle."

- Aristotle section at EpistemeLinks

- A brief biography and e-texts presented one chapter at a time

- Quotes by Aristotle

- Aristotle and Indian logic

- March 7, 322 B.C.E. - The Death of Aristotle

- Large collection of Aristotle's texts, presented page by page

- Source of most of the Biography and Methodology sections, as well as more overview

- John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson. Aristotle at the MacTutor archive

| Logic Portal |

| Philosophy | |

|---|---|

| Topics | Category listings | Eastern philosophy · Western philosophy | History of philosophy (ancient • medieval • modern • contemporary) |

| Lists | Basic topics · Topic list · Philosophers · Philosophies · Glossary · Movements · More lists |

| Branches | Aesthetics · Ethics · Epistemology · Logic · Metaphysics · Political philosophy |

| Philosophy of | Education · Economics · Geography · Information · History · Human nature · Language · Law · Literature · Mathematics · Mind · Philosophy · Physics · Psychology · Religion · Science · Social science · Technology · Travel ·War |

| Schools | Actual Idealism · Analytic philosophy · Aristotelianism · Continental Philosophy · Critical theory · Deconstructionism · Deontology · Dialectical materialism · Dualism · Empiricism · Epicureanism · Existentialism · Hegelianism · Hermeneutics · Humanism · Idealism · Kantianism · Logical Positivism · Marxism · Materialism · Monism · Neoplatonism · New Philosophers · Nihilism · Ordinary Language · Phenomenology · Platonism · Positivism · Postmodernism · Poststructuralism · Pragmatism · Presocratic · Rationalism · Realism · Relativism · Scholasticism · Skepticism · Stoicism · Structuralism · Utilitarianism · Virtue Ethics |

| Topics about Ancient Greece | |

|---|---|

| Places | Aegean Sea • Hellespont • Macedon • Sparta • Athens • Corinth • Thebes • Thermopylae • Antioch • Alexandria • Pergamon • Miletus • Delphi • Olympia • Troy |

| Life | Agriculture • Art • Cuisine • Economy • Law • Medicine • Paideia • Pederasty • Pottery • Prostitution • Slavery • Technology • Olympic Games |

| Philosophers | Pythagoras • Heraclitus • Parmenides • Protagoras • Empedocles • Democritus • Socrates • Plato • Aristotle • Zeno • Epicurus |

| Authors | Homer • Hesiod • Pindar • Sappho • Aeschylus • Sophocles •

Euripides • Aristophanes • Menander • Herodotus • Thucydides • Xenophon • Plutarch • Lucian • Polybius • Aesop |

| Buildings | Parthenon • Temple of Artemis • Acropolis • Ancient Agora • Arch of Hadrian • Temple of Zeus at Olympia • Colossus of Rhodes • Temple of Hephaestus • Samothrace temple complex |

| Chronology | Aegean civilization • Minoan Civilization • Mycenaean civilization • Greek dark ages • Classical Greece • Hellenistic Greece • Roman Greece |

| People of Note | Alexander The Great • Lycurgus • Pericles • Alcibiades • Demosthenes • Themistocles |

| Art and Sculpture | Kouroi • Korai • Kritios Boy • Doryphoros • Statue of Zeus • Discobolos • Aphrodite of Knidos • Laocoön • Phidias • Euphronios • Polykleitos • Myron |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

- This article incorporates material from Aristotle on PlanetMath, which is licensed under the GFDL.

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Aristotle |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Ἀριστοτέλης (Greek) |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Greek philosopher |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 384 B.C.E. |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Stageira |

| DATE OF DEATH | March 7, 322 B.C.E. |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Chalcis |

az:Aristotel ba:Аристотель be:Арыстоцель be-x-old:Арыстоцель br:Aristoteles fy:Aristoteles gd:Aristotle jv:Aristoteles lad:Aristoteles cdo:Ā-lī-sê̤ṳ-dŏ̤-dáik nds-nl:Aristoteles new:एरिस्टोटल nov:Aristotéles sq:Aristoteli sh:Aristotel kab:Aristot tg:Арасту ur:ارسطو

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.