Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus of Rhodes was a giant statue of the Greek god Helios, erected on the Greek island of Rhodes by Chares of Lindos, a student of sculptor Lysippos, between 292 and 280 B.C.E. It is one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Before its destruction from an earthquake, the Colossus of Rhodes stood 70 cubits tall, around 110 feet, making it the tallest statue of the ancient world.

Rhodes is an island situated in the eastern Aegean Sea. It lies approximately 11 miles (18 kilometers) west of Turkey's shores, situated between the Greek mainland and the island of Cyprus. The citizens of its capital, also called Rhodes, built the Colossus as a victory monument after resisting a military invasion. The Colossus has been compared in literature and lore to the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor. The two statues are roughly the same size.

Erection of the statue

The Colossus was originally built as a victory monument by the people of Rhodes after they successfully resisted an attack by a powerful army in the aftermath of the division of Alexander the Great's empire. Alexander died at an early age in 323 B.C.E. without having time to put into place any plans for his succession. Fighting broke out among his generals, the Diadochi, with three of them eventually dividing up much of his empire in the Mediterranean area. During the fighting Rhodes had sided with Ptolemy, and when Ptolemy eventually took control of Egypt, Rhodes and Ptolemaic Egypt, forming an alliance that controlled much of the trade in the eastern Mediterranean.

Another of Alexander's generals, Antigonus I Monophthalmus, was upset by this turn of events. In 305 B.C.E. he had his son Demetrius Poliorcetes, also a general, invade Rhodes with an army of 40,000. However, the city was well defended, and Demetrius—whose name "Poliorcetes" signifies the "besieger of cities"—had to start construction of a number of massive siege towers in order to gain access to the walls. The first was mounted on six ships, but these were capsized in a storm before they could be used. He tried again with a larger, land-based tower named Helepolis, but the Rhodian defenders stopped this by flooding the land in front of the walls so that the rolling tower could not move. In 304 B.C.E. a relief force of ships sent by Ptolemy arrived, and Demetrius' army abandoned the siege, leaving most of their siege equipment.

To celebrate their victory, the Rhodians sold the equipment left behind for 300 talents[1] and decided to build a colossal statue of their patron god, Helios. Construction was left to the direction of Chares, a native of Lindos in Rhodes, who had been involved with large-scale statues before. His teacher, the sculptor Lysippus, had constructed one 60-foot-high, bronze statue of Zeus at Tarentium. In order to pay for the construction of the Colossus, the Rhodians sold all of the siege equipment that Demetrius left behind.

Construction

Ancient accounts, which differ to some degree, describe the structure as being built around several stone columns (or towers of blocks) forming the interior of the structure, which stood on a 50-foot-high, white marble pedestal near the Mandraki harbor entrance. Other sources place the Colossus on a breakwater in the harbor.

Iron beams were embedded in the brick towers, and bronze plates attached to the bars formed the visible skin of the sculpture. Much of the iron and bronze was reforged from the various weapons Demetrius's army left behind, and the abandoned second siege tower was used for scaffolding around the lower levels during construction. Upper portions were built with the use of a large earthen ramp. The statue itself was over 110 feet tall, somewhere near the harbor entrance to Rhodes. After 12 years, in 280 B.C.E., the statue was completed. During construction, builders would pile mounds of dirt around the sides of the Colossus to aid in construction. To an observer it may have looked like a volcano-like sculpture. Upon completion all of the dirt was moved and the colossus was left to stand alone.

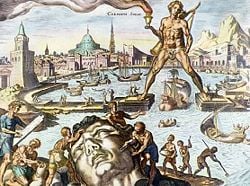

The "harbor-straddling Colossus" was a figment of later imaginations. Many older illustrations (above) show the statue with one foot on either side of the harbor mouth with ships passing under it:

- "The brazen giant of Greek fame, with conquering limbs astride from land to land"—The New Colossus (poem inscribed at the base of the Statue of Liberty).

In Shakespeare's play Julius Caesar, Cassius (I,ii,136–38) says of Caesar:

- Why man, he doth bestride the narrow world

- Like a Colossus, and we petty men

- Walk under his huge legs and peep about

- To find ourselves dishonorable graves

Shakespeare alludes to the Colossus also in Troilus and Cressida (Ch. 5) and in Henry IV, Part 1 (Ch. 1).

While these fanciful images from poetry feed the misconception, mechanical engineers believe it was highly unlikely that the Colossus could have straddled the harbor (Maryon, 1956). Arguments against such an open-legged construction include:

- If the completed statue straddled the harbor, the entire mouth of the harbor would have been effectively closed during the entirety of the construction. Moreover, the ancient Rhodians did not have the means to dredge and re-open the harbor after construction.

- The statue fell in 224 B.C.E.: if it straddled the harbor mouth, it would have entirely blocked the harbor rather than falling on the land as described in the ancient sources.

- Even ignoring these objections, the statue was made of bronze, and an engineering analysis indicated that the Colossus could not have been built with its legs apart without collapsing from its own weight.

Destruction

The statue stood for only 56 years until Rhodes was hit by an earthquake in 224 B.C.E. The statue snapped at the knees and fell over onto the land. Ptolemy III offered to pay for the reconstruction of the statue, but an oracle made the Rhodians afraid that they had offended Helios, and they declined to rebuild it. The remains lay on the ground as described by Strabo (xiv.2.5) for over eight hundred years, and even broken they were so impressive that many traveled to see them. Pliny the Elder remarked that few people could wrap their arms around the fallen thumb and that each of its fingers was larger than most statues.

In 654 an Arab force under Muawiyah I captured Rhodes, and according to the chronicler Theophanes the Confessor,[2] the remains were sold to a traveling salesman from Edessa, Mesopotamia. The buyer had the statue broken down, and transported the bronze scrap on the backs of nine hundred camels to his home. Pieces continued to turn up for sale for years, after being found along the caravan route.

Modern times

- Media reports in 1989 initially suggested that large stones found on the seabed off the coast of Rhodes might have been the remains of the Colossus; however this theory was later rejected by most scholars.

- Sylvia Plath's poem "The Colossus" refers to the Colossus of Rhodes. Perhaps the most famous reference to the Colossus, however, is in the poem, "The New Colossus," by Emma Lazarus, written in 1883 and inscribed on a plaque at the Statue of Liberty in New York City's harbor.

- Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

- With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

- Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

- A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

- Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

- Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

- Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

- The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

- "Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!" cries she

- With silent lips. "Give me your tired, your poor,

- Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

- The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

- Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

- I lift my lamp beside the golden door!"

- There has been much debate as to whether to build a replica of the Colossus. Those in favor the idea say it would boost tourism in Rhodes greatly, but those against construction say it would cost too large an amount over US$134 million. This idea has been revived many times since it was first proposed in 1970.

In November 2008, it was announced that the Colossus of Rhodes was to be rebuilt. According to Dr. Dimitris Koutoulas, who is heading the project in Greece, rather than reproducing the original Colossus, the new structure will be a, "highly, highly innovative light sculpture, one that will stand between 60 and 100 metres tall so that people can physically enter it." The project is expected to cost up to €200m which will be provided by international donors and the German artist Gert Hof. The new Colossus will adorn an outer pier in the harbour area of Rhodes, where it will be visible to passing ships. Koutoulas said, "Although we are still at the drawing board stage, Gert Hof's plan is to make it the world's largest light installation, a structure that has never before been seen in any place of the world."[3]

Notes

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History 34:18. (Loeb Classical Library, 1938; Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, ISBN 978-0674993648).

- ↑ See also Constantine VII Porphyrogenitos, De administrando imperio(Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1967. ISBN 978-0884020219), xx-xxi.

- ↑ Helena Smith, Colossus of Rhodes to be rebuilt as giant light sculpture, Guardian UK Online, (16 November 2008). Retrieved October 19, 2011.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ashley, James R. Macedonian Empire. McFarland & Company, 2004. ISBN 0786419180

- Franzen, Nils-Olof. Agaton Sax and the Colossus of Rhodes. E P Dutton, 1982. ISBN 978-0233960272

- Haynes, D. E. L. Philo of Byzantium and the Colossus of Rhodes. The Journal of Hellenic Studies 77(2) (1957): 311-312. A response to Maryon.

- Lawrence, Caroline. The Colossus of Rhodes. Roaring Brooks Press, 2006. ISBN 978-1596430822

- Maryon, Herbert. "The Colossus of Rhodes." The Journal of Hellenic Studies 76 (1956): 68-86. A sculptor's speculations on the Colossus of Rhodes.

- Pliny the Elder. Pliny: Natural History, Volume I, Books 1-2. Loeb Classical Library, 1938. ISBN 978-0674993648

- Porphyrogenitus, Constantine. Constantine Porphyrogenitus: De Administrando Imperio edited by Gyula Moravcsik and translated by R. J. H. Jenkins. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, 1967. ISBN 978-0884020219

External links

All links retrieved January 7, 2024.

- The Colossus of Rhodes RhodesGuide.com

- The Colossus of Rhodes The Museum of Unnatural Mystery

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.