Ancient Greek literature

This article is part of the series on: History of Greece | |||

| Prehistory of Greece | |||

| Helladic Civilization | |||

| Cycladic Civilization | |||

| Minoan Civilization | |||

| Mycenaean Civilization | |||

| Greek Dark Ages | |||

| Ancient Greece | |||

| Archaic Greece | |||

| Classical Greece | |||

| Hellenistic Greece | |||

| Roman Greece | |||

| Medieval Greece | |||

| Byzantine Empire | |||

| Ottoman Greece | |||

| Modern Greece | |||

| Greek War of Independence | |||

| Kingdom of Greece | |||

| Axis Occupation of Greece | |||

| Greek Civil War | |||

| Military Junta | |||

| The Hellenic Republic | |||

| Topical History | |||

| Economic history of Greece | |||

| Military history of Greece | |||

| Constitutional history of Greece | |||

| Names of the Greeks | |||

| History of Greek art | |||

Ancient Greek literature refers to literature written in the Greek language from the earliest texts, dating back to the early Archaic period, until the fourth century C.E. This period of Greek literature stretches from Homer until the rise of Alexander the Great. Ancient Greek literature, together with the Hebrew Bible, provides the foundation for all of Western literature.

In addition to history and philosophy, Ancient Greek literature is famous for its epic and lyric poetry as well as its drama, both tragedy and comedy. Ancient Greek tragedy remains among the highest literary and cultural achievements in Western literature.

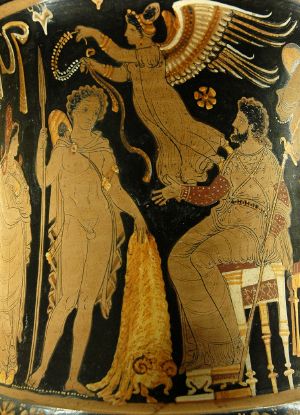

Most of the epic poetry and tragedy has its roots in Ancient Greek religion and Greek mythology. Greek mythology has exercised an extensive and profound influence on the culture, arts and literature of Western civilization. Though the ancient Greek religions based upon these tales have long since faded into obscurity, Greek myths remain alive and vibrant, largely through the epic poetry and tragedies of Ancient Greek literature, and are rich sources for Western fiction, poetry, film, and visual art.

Classical and pre-classical antiquity

The earliest known Greek writings are Mycenaean, written in the Linear B syllabary on clay tablets. These documents contain prosaic records largely concerned with trade (lists, inventories, receipts, and so on); no real literature has been discovered. Several theories have been advanced to explain this curious absence. One is that Mycenaean literature, like the works of Homer and other epic poems, was passed on orally, since the Linear B syllabary is not well-suited to recording the sounds of Greek. Another theory is that literary works, as the preserve of an elite, were written on finer materials such as parchment, which have not survived.

Epic poetry

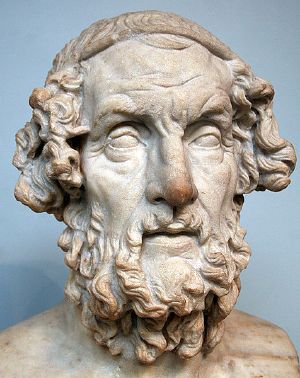

At the beginning of Greek literature stand the two monumental works of Homer, the Iliad and the Odyssey. The figure of Homer is shrouded in mystery. Although the works as they now stand are credited to him, it is certain that their roots reach far back before his time. The Iliad is the famous story about the Trojan War. The work examines the war through the person of Achilles, who embodied the Greek heroic ideal.

While the Iliad is purely a work of tragedy, the Odyssey is a mixture of tragedy and comedy. It is the story of Odysseus, one of the warriors at Troy. After ten years fighting the war, he spends another ten years sailing back home to his wife and family. During his ten-year voyage, he loses all of his comrades and ships and makes his way home to Ithaca disguised as a beggar. Both of these works were based on ancient legends. The stories are told in language that is simple, direct, and eloquent. Both are as fascinatingly readable today as they were in Ancient Greece.

The other great poet of the preclassical period was Hesiod. Unlike Homer, Hesiod speaks of himself in his poetry. Nothing is known about him from any source external to his own poetry. He was a native of Boeotia in central Greece, and is thought to have lived and worked around 700 B.C.E. His two works were Works and Days and Theogony. The first is a faithful depiction of the poverty-stricken country life he knew so well, and it sets forth principles and rules for farmers. Theogony is a systematic account of creation and of the gods. It vividly describes the ages of humankind, beginning with a long-past Golden Age. Together the works of Homer and Hesiod served as a kind of Bible for the Greeks. Homer told the story of a heroic past, and Hesiod dealt with the practical realities of daily life.

Lyric poetry

The type of poetry called lyric got its name from the fact that it was originally sung by individuals or a chorus accompanied by the lyre. The first of the lyric poets was probably Archilochus of Paros, circa 700 B.C.E. Only fragments remain of his work, as is the case with most of the lyric poets. The few remnants suggest that he was an embittered adventurer who led a very turbulent life.

The two major lyric poets were Sappho and Pindar. Sappho, who lived in the period from 610 B.C.E. to 580 B.C.E., has always been admired for the beauty of her writing. Her themes were personal. They dealt with her friendships with and dislikes of other women, though her brother Charaxus was the subject of several poems. Unfortunately, only fragments of her poems remain. With Pindar the transition has been made from the preclassical to the classical age. He was born about 518 B.C.E. and is considered the greatest of the Greek lyricists. His masterpieces were the poems that celebrated athletic victories in the games at Olympia, Delphi, Nemea, and the Isthmus of Corinth.

Tragedy

The Greeks invented drama and produced masterpieces that are still reckoned as one of drama's crowning achievements. In the age that followed the Greco-Persian Wars, the awakened national spirit of Athens was expressed in hundreds of superb tragedies based on heroic and legendary themes of the past. The tragic plays grew out of simple choral songs and dialogues performed at festivals of the god Dionysus. Wealthy citizens were chosen to bear the expense of costuming and training the chorus as a public and religious duty. Attendance at the festival performances was regarded as an act of worship. Performances were held in the great open-air theater of Dionysus in Athens. All of the greatest poets competed for the prizes offered for the best plays.

Of the hundreds of dramas written and performed during the classical age, only a limited number of plays by three authors have survived: Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides. The earliest of the three was Aeschylus, who was born in 525 B.C.E. He wrote between 70 and 90 plays, of which only seven remain. Many of his dramas were arranged as trilogies, groups of three plays on a single theme. The Oresteia consisting of Agamemnon, Choephoroi (The Libation Bearers), and Eumenides is the only surviving trilogy. The Persai (The Persians) is a song of triumph for the defeat of the Persians. Prometheus Bound is a retelling of the legend of the Titan Prometheus, a superhuman who stole fire from heaven and gave it to humankind.

For about 16 years, between 484 and 468 B.C.E., Aeschylus carried off prize after prize. But in 468 his place was taken by a new favorite, Sophocles. Sophocles' life covered nearly the whole period of Athens' "golden age." He won more than 20 victories at the Dionysian festivals and produced more than 100 plays, only seven of which remain. His drama Antigone is typical of his work: its heroine is a model of womanly self-sacrifice. He is probably better known, though, for Oedipus the King and its sequel, Oedipus at Colonus.

The third of the great tragic writers was Euripides. He wrote at least 92 plays. Sixty-seven of these are known in the twentieth century, some just in part or by name only. Only 19 still exist in full. One of these is Rhesus, which is believed by some scholars not to have been written by Euripides. His tragedies are about real men and women rather than the heroic figures of myth. The philosopher Aristotle called Euripides the most tragic of the poets because his plays were the most moving. His dramas are performed on the modern stage more often than those of any other ancient poet. His best-known work is probably the powerful Medea, but his Alcestis, Hippolytus, Trojan Women, Orestes, and Electra are no less brilliant.

Comedy

Like tragedy, comedy arose from a ritual in honor of Dionysus, but in this case the plays were full of frank obscenity, abuse, and insult. In Athens, the comedies became an official part of the festival celebration in 486 B.C.E., and prizes were offered for the best productions. As with the tragedians, few works still remain of the great comedic writers. Of the works of earlier writers, only some plays by Aristophanes exist. His work remains one of the finest examples of comic presentation and his plays remain popular. He poked fun at everyone and every institution. Aristophanes' plays set the standard for boldness of fantasy, for merciless insult, for unqualified indecency, and for outrageous and free political criticism. In The Birds he held up Athenian democracy to ridicule. In The Clouds, he attacked the philosopher Socrates. In Lysistrata he denounced war. Only 11 of his plays have survived.

During the fourth century B.C.E., there developed a new form called New Comedy. Menander is considered the best of its writers. Nothing remains from his competitors, however, so it is difficult to make comparisons. The plays of Menander, of which only the Dyscolus (Misanthrope) now exists, did not deal with the great public themes such as those of Aristophanes. He concentrated instead on fictitious characters from everyday life: stern fathers, young lovers, intriguing slaves, and others. In spite of his narrower focus, the plays of Menander influenced later generations. They were freely adapted by the Roman poets Plautus and Terence in the third and second centuries B.C.E. The comedies of the French playwright Molière are reminiscent of those by Menander.

Historiography

Greece's classical age produced two of the pioneers of history: Herodotus and Thucydides. Herodotus is commonly called the father of history, and his "History" contains the first truly literary use of prose in Western literature. Of the two, Thucydides was the better historian by modern standards. His critical use of sources, inclusion of documents, and laborious research made his History of the Peloponnesian War a significant influence on later generations of historians.

A third historian of ancient Greece, Xenophon, began his 'Hellenica' where Thucydides ended his work about 411 B.C.E. and carried his history to 362 B.C.E. His writings were superficial in comparison to those of Thucydides, but he wrote with authority on military matters. His best work is the Anabasis, an account of his participation in a Greek mercenary army that tried to help the Persian Cyrus expel his brother from the throne. Xenophon also wrote three works in praise of the philosopher Socrates: Apology, Symposium, and Memorabilia. Although both Xenophon and Plato knew Socrates, their accounts are very different, providing an interesting comparison between the view of the military historian to that of the poet-philosopher.

Philosophy

The greatest achievement of the fourth century was in philosophy. There were many Greek philosophers, but three names tower above the rest: Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle. It is impossible to calculate the enormous influence these thinkers have had on Western society. Alfred North Whitehead once claimed that all of philosophy is but a footnote to Plato. Socrates wrote nothing, but his thought (or a reasonable presentation of it) is believed to be given by Plato's early Socratic dialogues. Aristotle is virtually without rivals among scientists and philosophers. The first sentence of his Metaphysics reads: "All men by nature desire to know." He has, therefore, been called the "Father of those who know." His medieval disciple Thomas Aquinas referred to him simply as "the Philosopher."

Aristotle was a student at Plato's Academy, and it is known that like his teacher he wrote dialogues, or conversations. None of these exists today. The body of writings that has come down to the present probably represents lectures that he delivered at his own school in Athens, the Lyceum. Even from these books the enormous range of his interests is evident. He explored matters other than those that are today considered philosophical. The treatises that exist cover logic, the physical and biological sciences, ethics, politics, and constitutional government. There are also treatises on The Soul and Rhetoric. His Poetics has had an enormous influence on literary theory and served as an interpretation of tragedy for more than 2,000 years. With his death in 322 B.C.E., the classical era of Greek literature drew to a close. In the successive centuries of Greek writing there was never again such a brilliant flowering of genius as appeared in the fifth and fourth centuries B.C.E. For today's readers there are excellent modern translations of classical Greek literature. Most are available in paperback editions.

Hellenistic Age

By 338 B.C.E. all of the Greek city-states except Sparta had been conquered by Philip II of Macedon. Philip's son, Alexander the Great, greatly extended his father's conquests. In so doing he inaugurated what is called the Hellenistic Age. Alexander's conquests were in the East, and Greek culture shifted first in that direction. Athens lost its preeminent status as the leader of Greek culture, and it was replaced temporarily by Alexandria, Egypt.

The city of Alexandria in northern Egypt became, from the third century B.C.E., the outstanding center of Greek culture. It also soon attracted a large Jewish population, making it the largest center for Jewish scholarship in the ancient world. In addition, it later became a major focal point for the development of Christian thought. The Museum, or Shrine to the Muses, which included the library and school, was founded by Ptolemy I. The institution was from the beginning intended as a great international school and library. The library, eventually containing more than a half million volumes, was mostly in Greek. It served as a repository for every Greek work of the classical period that could be found.

Hellenistic poetry

Later Greek poetry flourished primarily in the third century B.C.E. The chief poets were Theocritus, Callimachus, and Apollonius of Rhodes. Theocritus, who lived from about 310 to 250 B.C.E., was the creator of pastoral poetry, a type that the Roman Virgil mastered in his Eclogues. Of his rural-farm poetry, Harvest Home is considered the best work. He also wrote mimes, poetic plays set in the country as well as minor epics and lyric poetry.

Callimachus, who lived at the same time as Theocritus, worked his entire adult life at Alexandria, compiling a catalog of the library. Only fragments of his poetry survive. The most famous work was Aetia (Causes). An elegy in four books, the poem explains the legendary origin of obscure customs, festivals, and names. Its structure became a model for the work of the Roman poet, Ovid. Of his elegies for special occasions, the best known is the "Lock of Berenice," a piece of court poetry that was later adapted by the Roman, Catullus. Callimachus also wrote short poems for special occasions and at least one short epic, the "Ibis," which was directed against his former pupil, Apollonius.

Apollonius of Rhodes was born about 295 B.C.E. He is best remembered for his epic the Argonautica, about Jason and his shipmates in search of the golden fleece. Apollonius studied under Callimachus, with whom he later quarreled. He also served as librarian at Alexandria for about 13 years. Apart from the Argonautica, he wrote poems on the foundation of cities as well as a number of epigrams. The Roman poet Virgil was strongly influenced by the Argonautica in writing his Aeneid. Lesser third-century poets include Aratus of Soli and Herodas. Aratus wrote the "Phaenomena," a poetic version of a treatise on the stars by Eudoxus of Cnidus, who had lived in the fourth century. Herodas wrote mimes reminiscent of those of Theocritus. His works give a hint of the popular entertainment of the times. Mime and pantomime were a major form of entertainment during the early Roman Empire.

The rise of Rome

While the transition from city-state to empire affected philosophy a great deal, shifting the emphasis from political theory to personal ethics, Greek letters continued to flourish both under the Successors (especially the Ptolemies) and under Roman rule. Romans with literary or rhetorical talent looked to Greek models, and Greek literature of all types continued to be read and produced both by native speakers of Greek and later by Roman authors as well. A notable characteristic of this period was the expansion of literary criticism as a genre, particularly as exemplified by Demetrius, Pseudo-Longinus and Dionysius of Halicarnassus. The Greek novel, typified by Chariton's Callirhoe and the Hero and Leander of Pseudo-Musaeus, also emerged. The New Testament, written by various authors in varying qualities of Koine Greek also hails from this period, and include a unique literary genre, the Gospels, as well as the Epistles of Saint Paul.

Historiography

The significant historians in the period after Alexander were Timaeus, Polybius, Diodorus Siculus, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Appian of Alexandria, Arrian, and Plutarch. The period of time they cover extended from late in the fourth century B.C.E. to the second century C.E.

Timaeus was born in Sicily but spent most of his life in Athens. His History, though lost, is significant because of its influence on Polybius. In 38 books it covered the history of Sicily and Italy to the year 264 B.C.E., the starting point of Polybius' work. Timaeus also wrote the "Olympionikai," a valuable chronological study of the Olympic Games. Polybius was born about 200 B.C.E. He was brought to Rome as a hostage in 168. In Rome he became a friend of the general Scipio Aemilianus. He probably accompanied the general to Spain and North Africa in the wars against Carthage. He was with Scipio at the destruction of Carthage in 146. The history on which his reputation rests consisted of 40 books, five of which have been preserved along with various excerpts. They are a vivid recreation of Rome's rise to world power. A lost book, Tactics, covered military matters.

Diodorus Siculus lived in the first century B.C.E., the time of Julius Caesar and Augustus. He wrote a universal history, Bibliotheca historica, in 40 books. Of these, the first five and the 11th through the 20th remain. The first two parts covered history through the early Hellenistic era. The third part takes the story to the beginning of Caesar's wars in Gaul, now France. Dionysius of Halicarnassus lived late in the first century B.C.E. His history of Rome from its origins to the First Punic War (264 to 241 B.C.E.) is written from a Roman point of view, but it is carefully researched. He also wrote a number of other treatises, including On Imitation, Commentaries on the Ancient Orators, and On the Arrangement of Words.

Appian and Arrian both lived in the second century C.E. Appian wrote on Rome and its conquests, while Arrian is remembered for his work on the campaigns of Alexander the Great. Arrian served in the Roman army. His book therefore concentrates heavily on the military aspects of Alexander's life. Arrian also wrote a philosophical treatise, the Diatribai, based on the teachings of his mentor Epictetus. Best known of the late Greek historians to modern readers is Plutarch, who died about 119 C.E. His Parallel Lives of great Greek and Roman leaders has been read by every generation since the work was first published. His other surviving work is the Moralia, a collection of essays on ethical, religious, political, physical, and literary topics.

Science and mathematics

Eratosthenes of Alexandria, who died about 194 B.C.E., wrote on astronomy and geography, but his work is known mainly from later summaries. He is credited with being the first person to measure the Earth's circumference. Much that was written by the mathematicians Euclid and Archimedes has been preserved. Euclid is known for his Elements, much of which was drawn from his predecessor Eudoxus of Cnidus. The Elements is a treatise on geometry, and it has exerted a continuing influence on mathematics. From Archimedes several treatises have come down to the present. Among them are Measurement of the Circle, in which he worked out the value of pi; Method Concerning Mechanical Theorems, on his work in mechanics; The Sand Reckoner; and On Floating Bodies. A manuscript of his works is currently being studied.

The physician Galen, in the history of ancient science, is the most significant person in medicine after Hippocrates, who laid the foundation of medicine in the fifth century B.C.E. Galen lived during the second century C.E. He was a careful student of anatomy, and his works exerted a powerful influence on medicine for the next 1,400 years. Strabo, who died about 23 C.E., was a geographer and historian. His Historical Sketches in 47 volumes has nearly all been lost. His Geographical Sketches remain as the only existing ancient book covering the whole range of people and countries known to the Greeks and Romans through the time of Augustus. Pausanias, who lived in the second century C.E., was also a geographer. His Description of Greece is an invaluable guide to what are now ancient ruins. His book takes the form of a tour of Greece, starting in Athens. The accuracy of his descriptions has been proved by archaeological excavations.

The scientist of the Roman period who had the greatest influence on later generations was undoubtedly the astronomer Ptolemy. He lived during the second century C.E., though little is known of his life. His masterpiece, originally entitled The Mathematical Collection, has come to the present under the title Almagest, as it was translated by Arab astronomers with that title. It was Ptolemy who devised a detailed description of an Earth-centered universe, a notion that dominated astronomical thinking for more than 1,300 years. The Ptolemaic view of the universe endured until Copernicus, Galileo, Kepler, and other early modern astronomers replaced it with heliocentrism.

Philosophy

Later philosophical works were no match for Plato and Aristotle. Epictetus, who died about 135 C.E., was associated with the moral philosophy of the Stoics. His teachings were collected by his pupil Arrian in the Discourses and the Encheiridion (Manual of Study). Diogenes Laertius, who lived in the third century, wrote Lives, Teachings, and Sayings of Famous Philosophers, a useful sourcebook. Another major philosopher of his period was Plotinus. He transformed Plato's philosophy into a school called Neoplatonism. His Enneads had a wide-ranging influence on European thought until at least the seventeenth century

Legacy

Virtually all of Western literature has been influenced by Ancient Greek literature. Its influence is so ubiquitous that virtually every major artist, from William Shakespeare to James Joyce is in its debt. In addition to modern literature, its influence has been felt in other ways. The foundations of Sigmund Freud's psychoanalysis originate in the Oedipus complex, which is based on Sophocles' tragedy.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Beye, Charles Rowan. 1987. Ancient Greek Literature and Society. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0801418747.

- Easterling, P.E., and B.M.W. Knox (eds.). 1985. The Cambridge History of Classical Literature: Greek literature: Volume 1. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521210429.

- Flacelière, Robert. 1964. A Literary History of Greece. Translated by Douglas Garman. Chicago: Aldine Pub. Co. OCLC 308150

- Gutzwiller, Kathryn. 2007. A Guide to Hellenistic Literature. Blackwell. ISBN 0631233229.

- Hadas, Moses. 1950. A History of Greek Literature. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. OCLC 307596

- Lesky, Albin. 1966. A History of Greek Literature. Translated by James Willis and Cornelis de Heer. New York: Crowell. OCLC 308152

- Schmidt, Michael. 2004. The First Poets: Lives of the Ancient Greek Poets. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0297643940.

- Trypanis, C.A. 1981. Greek Poetry from Homer to Seferis. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226813165.

- Whitmarsh, Tim. 2004. Ancient Greek Literature. Cambridge: Polity Press. ISBN 0745627927.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.