Difference between revisions of "Halloween" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 47: | Line 47: | ||

The [[imagery]] surrounding Halloween is largely an amalgamation of the Halloween [[season]] itself, works of [[Gothic fiction|Gothic]], and [[horror fiction|horror]] literature, nearly a century of work from American [[filmmaker]]s and [[graphic artist]]s, and a rather commercialized take on the dark and mysterious. Halloween imagery tends to involve [[death]], [[evil]], [[Magic (paranormal)|magic]], or [[mythical creature|mythical monster]]s. Traditional characters include the [[Devil]], the [[Grim Reaper]], [[ghost]]s, [[ghoul]]s, [[demon]]s, [[witchcraft|witch]]es, pumpkin-men, [[goblin]]s, [[vampire]]s, [[werewolf|werewolves]], [[zombie]]s, [[mummy|mummies]], [[skeleton (undead)|skeleton]]s, [[black cat]]s, [[spider]]s, [[bat]]s, [[owl]]s, [[crow]]s, and [[vulture]]s. | The [[imagery]] surrounding Halloween is largely an amalgamation of the Halloween [[season]] itself, works of [[Gothic fiction|Gothic]], and [[horror fiction|horror]] literature, nearly a century of work from American [[filmmaker]]s and [[graphic artist]]s, and a rather commercialized take on the dark and mysterious. Halloween imagery tends to involve [[death]], [[evil]], [[Magic (paranormal)|magic]], or [[mythical creature|mythical monster]]s. Traditional characters include the [[Devil]], the [[Grim Reaper]], [[ghost]]s, [[ghoul]]s, [[demon]]s, [[witchcraft|witch]]es, pumpkin-men, [[goblin]]s, [[vampire]]s, [[werewolf|werewolves]], [[zombie]]s, [[mummy|mummies]], [[skeleton (undead)|skeleton]]s, [[black cat]]s, [[spider]]s, [[bat]]s, [[owl]]s, [[crow]]s, and [[vulture]]s. | ||

| − | Particularly in America, [[symbolism]] is inspired by classic [[horror film]]s (which contain fictional figures like [[Frankenstein's monster]]), and to a lesser extent by [[science fiction]] ([[ | + | Particularly in America, [[symbolism]] is inspired by classic [[horror film]]s (which contain fictional figures like [[Frankenstein's monster]]), and to a lesser extent by [[science fiction]] ([[Extraterrestrial life|alien]]s, [[UFO]]s, and [[superhero]]es). Elements of the autumn season, such as pumpkins, corn husks, and [[scarecrow]]s, are also prevalent. |

The three main colors associated with Halloween are [[pumpkin]] [[orange (color)|orange]]; [[night]] or [[death]] [[black]]; and [[moon]], [[ghost]] or [[skeleton]] [[white]]. | The three main colors associated with Halloween are [[pumpkin]] [[orange (color)|orange]]; [[night]] or [[death]] [[black]]; and [[moon]], [[ghost]] or [[skeleton]] [[white]]. | ||

Revision as of 18:47, 21 February 2009

| Halloween Hallowe'en | |

|---|---|

| |

| Jack-o'-lantern | |

| Also called | All Hallows Eve All Saints' Eve |

| Observed by | Numerous Western countries (see article) |

| Type | Secular with roots in Christianity and Paganism |

| Date | October 31 |

| Celebrations | Varies by region but includes trick-or-treating, ghost tours, apple bobbing, costume parties, carving jack-o'-lanterns |

| Related to | Samhain, All Saints Day |

Halloween (or Hallowe’en) is a holiday celebrated on October 31. It has roots in the Celtic festival of Samhain and the Christian holy day of All Saints. It is largely a secular celebration, but some Christians and Pagans have expressed strong feelings about its religious overtones. Irish immigrants carried versions of the tradition to North America during Ireland's Great Famine of 1846. The day is often associated with the colors orange and black, and is strongly associated with symbols such as the jack-o'-lantern. Halloween activities include trick-or-treating, ghost tours, bonfires, costume parties, visiting haunted attractions, carving jack-o'-lanterns, reading scary stories, and watching horror movies.

Origins

Halloween has origins in the ancient Celtic festival known as Samhain (Irish pronunciation: [ˈsˠaunʲ]; from the Old Irish samain, apparently derived from Gaulish samonios).[1] The festival of Samhain is a celebration of the end of the harvest season in Gaelic culture, and is sometimes regarded as the "Celtic New Year." Traditionally, the festival was a time used by the ancient Celtic pagans to take stock of supplies and slaughter livestock for winter stores.

The ancient Celts believed that on October 31, now known as Halloween, the boundary between the living and the deceased dissolved, and the dead become dangerous for the living by causing problems such as sickness or damaged crops. The festivals would frequently involve bonfires, into which the bones of slaughtered livestock were thrown. Costumes and masks were also worn at the festivals in an attempt to copy the evil spirits or placate them.

Etymology

The term "Halloween" is shortened from "All Hallows' Even" (both "even" and "eve" are abbreviations of "evening," but "Halloween" gets its "n" from "even") as it is the eve of "All Hallows' Day",[2] which is now also known as All Saints' Day. It was a day of religious festivities in various northern European Pagan traditions, until Popes Gregory III and Gregory IV moved the old Christian feast of All Saints' Day from May 13 (which had itself been the date of a pagan holiday, the Feast of the Lemures) to November 1. In the ninth century, the Church measured the day as starting at sunset, in accordance with the Florentine calendar. Although All Saints' Day is now considered to occur one day after Halloween, the two holidays were, at that time, celebrated on the same day.

Symbols

On Hallows' eve, the ancient Celts would place a skeleton on their window sill to represent the departed. Originating in Europe, these lanterns were first carved from a turnip or rutabaga. Believing that the head was the most powerful part of the body, containing the spirit and the knowledge, the Celts used the "head" of the vegetable to frighten off any superstitions. Welsh, Irish, and British myths are full of legends of the Brazen Head, which may be a folk memory of the widespread ancient Celtic practice of headhunting—the results of which were often nailed to a door lintel or brought to the fireside to speak their wisdom.

The "jack-o'-lantern" can be traced back to the Irish legend of Stingy Jack,[3] a greedy, gambling, hard-drinking old farmer. He tricked the devil into climbing a tree and trapped him by carving a cross into the tree trunk. In revenge, the devil placed a curse on Jack, condemning him to forever wander the earth at night with the only light he had: a candle inside of a hollowed turnip. The carving of pumpkins became associated with Halloween in North America, where pumpkins were not only readily available but much larger, making them easier to carve than turnips. Many families that celebrate Halloween carve a pumpkin into a frightening or comical face and place it on their doorstep after dark. The tradition of carving pumpkins, however, is known to have preceded the Great Famine period of Irish immigration. The carved pumpkin was originally associated with harvest time in America, and did not become specifically associated with Halloween until the mid-to-late nineteenth century.

The imagery surrounding Halloween is largely an amalgamation of the Halloween season itself, works of Gothic, and horror literature, nearly a century of work from American filmmakers and graphic artists, and a rather commercialized take on the dark and mysterious. Halloween imagery tends to involve death, evil, magic, or mythical monsters. Traditional characters include the Devil, the Grim Reaper, ghosts, ghouls, demons, witches, pumpkin-men, goblins, vampires, werewolves, zombies, mummies, skeletons, black cats, spiders, bats, owls, crows, and vultures.

Particularly in America, symbolism is inspired by classic horror films (which contain fictional figures like Frankenstein's monster), and to a lesser extent by science fiction (aliens, UFOs, and superheroes). Elements of the autumn season, such as pumpkins, corn husks, and scarecrows, are also prevalent.

The three main colors associated with Halloween are pumpkin orange; night or death black; and moon, ghost or skeleton white.

Activities

Trick-or-treating, guising

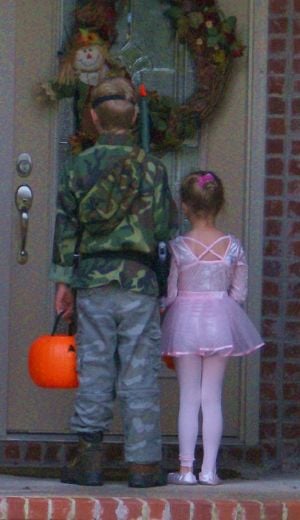

"Trick-or-treating" is a custom for children on Halloween. Children proceed in costume from house to house, asking for treats such as confectionery, or sometimes money, with the question, "Trick or treat?" The "trick" is an idle threat to perform mischief on the homeowners or their property if no treat is given.

In the United States, trick-or-treating is now one of the main traditions of Halloween and it has become socially expected that if one lives in a neighborhood with children one should purchase treats in preparation for trick-or-treaters. The tradition has also spread to Britain, Ireland, and other European countries, where similar local traditions have been influenced by the American Halloween customs.

The practice of dressing up in costumes and going door to door for treats on holidays dates back to the Middle Ages and includes Christmas wassailing. Trick-or-treating resembles the late medieval practice of souling, when poor folk would go door to door on Hallowmas (November 1), receiving food in return for prayers for the dead on All Souls Day (November 2). It originated in Ireland and Britain, although similar practices for the souls of the dead were found as far south as Italy. Shakespeare mentions the practice in his comedy The Two Gentlemen of Verona (1593), when Speed accuses his master of "puling [whimpering or whining] like a beggar at Hallowmas."[4]

However, there is no evidence that souling was ever practiced in North America, where trick-or-treating may have developed independent of any Irish or British antecedent. There is little primary documentation of masking or costuming on Halloween—in Ireland, the UK, or America—before 1900. Ruth Edna Kelley, in her 1919 history of the holiday, The Book of Hallowe'en, makes no mention of ritual begging in the chapter "Hallowe'en in America."[5] Kelley lived in Lynn, Massachusetts, a town with about 4,500 Irish immigrants, 1,900 English immigrants, and 700 Scottish immigrants in 1920. The thousands of Halloween postcards produced between the turn of the twentieth century and the 1920s commonly show children, but do not depict trick-or-treating.[6]

Halloween did not become a holiday in the United States until the nineteenth century, where lingering Puritan tradition restricted the observance of many holidays. American almanacs of the late-eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries do not include Halloween in their lists of holidays. The transatlantic migration of nearly two million Irish following the Irish Potato Famine (1845–1849) finally brought the holiday to the United States. Scottish emigration, primarily to Canada before 1870 and to the United States thereafter, brought the Scottish version of the holiday to each country. The main event for children of modern Halloween in the United States and Canada is trick-or-treating, in which children disguise themselves in costumes and go door to door in their neighborhoods, ringing each doorbell and yelling "Trick or treat!" to solicit a gift of candy or similar items.

Irish-American and Scottish-American societies held dinners and balls that celebrated their heritages, with perhaps a recitation of Robert Burns' poem "Halloween" or a telling of Irish legends, much as Columbus Day celebrations were more about Italian-American heritage than Columbus per se. Home parties centered on children's activities, such as apple bobbing, and various divination games often concerning future romance. Not surprisingly, pranks and mischief were common as well.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Halloween had turned into a night of vandalism, with destruction of property and cruelty to animals and people. Around 1912, the Boy Scouts, Boys Clubs, and other neighborhood organizations came together to encourage a safe celebration that would end the destruction that had become so common on this night. School posters during this time called for a "Sane Halloween." Children began to go door to door, receiving treats, rather than playing tricks on their neighbors. This helped to reduce the mischief, and by the 1930s, "beggar's nights" had become very popular. Trick-or-treating became widespread by the end of the 1930s.

The earliest known reference to ritual begging on Halloween in English speaking North America occurs in 1911, when a newspaper in Kingston, Ontario, near the border of upstate New York, reported that it was normal for the smaller children to go street "guising" on Halloween between 6:00 and 7:00 p.m., visiting shops and neighbors to be rewarded with nuts and candies for their rhymes and songs.[7] Another isolated reference to ritual begging on Halloween appears, place unknown, in 1915, with a third reference in Chicago in 1920.[8]

The earliest known use in print of the term "trick or treat" appears in 1927, from Blackie, Alberta, Canada:

Hallowe’en provided an opportunity for real strenuous fun. No real damage was done except to the temper of some who had to hunt for wagon wheels, gates, wagons, barrels, etc., much of which decorated the front street. The youthful tormentors were at back door and front demanding edible plunder by the word “trick or treat” to which the inmates gladly responded and sent the robbers away rejoicing.[9]

Trick-or-treating does not seem to have become a widespread practice until the 1930s, with the first U.S. appearances of the term in 1934,[10] and the first use in a national publication occurring in 1939.[11]

Almost all pre-1940 uses of the term "trick-or-treat" are from the western United States and Canada.[12] Trick-or-treating spread from the western United States eastward, stalled by sugar rationing that began in April 1942 during World War II and did not end until June 1947.

Early national attention to trick-or-treating was given in October 1947 issues of the children's magazines Jack and Jill and Children's Activities,[13] and by Halloween episodes of the network radio programs The Baby Snooks Show in 1946 and The Jack Benny Show and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet in 1948.[14] The custom had become firmly established in popular culture by 1952, when Walt Disney portrayed it in the cartoon Trick or Treat, Ozzie and Harriet were besieged by trick-or-treaters on an episode of their television show,[15] and UNICEF first conducted a national campaign for children to raise funds for the charity while trick-or-treating.[16]

Although some popular histories of Halloween have characterized trick-or-treating as an adult invention to rechannel Halloween activities away from vandalism, nothing in the historical record supports this theory. To the contrary, adults, as reported in newspapers from the mid-1930s to the mid-1950s, typically saw it as a form of extortion, with reactions ranging from bemused indulgence to anger.

Games

There are several games traditionally associated with Halloween parties. A common one is dunking or apple bobbing, in which apples float in a tub or a large basin of water; the participants must use their teeth to remove an apple from the basin. A variant of dunking involves kneeling on a chair, holding a fork between the teeth and trying to drop the fork into an apple. Another common game involves hanging up treacle or syrup-coated scones by strings; these must be eaten without using hands while they remain attached to the string, an activity that inevitably leads to a very sticky face.

Some games traditionally played at Halloween are forms of divination. In Puicíní, a game played in Ireland, a blindfolded person is seated in front of a table on which several saucers are placed. The saucers are shuffled, and the seated person then chooses one by touch; the contents of the saucer determine the person's life during the following year. In nineteenth-century Ireland, young women placed slugs in saucers sprinkled with flour. A traditional Irish and Scottish form of divining one's future spouse is to carve an apple in one long strip, then toss the peel over one's shoulder. The peel is believed to land in the shape of the first letter of the future spouse's name. This custom has survived among Irish and Scottish immigrants in the rural United States.

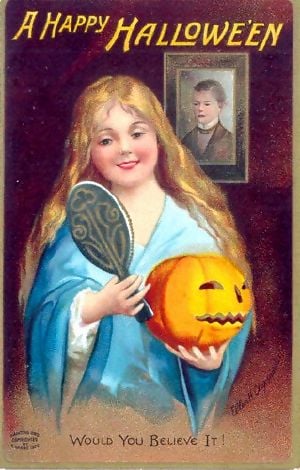

Unmarried women were frequently told that if they sat in a darkened room and gazed into a mirror on Halloween night, the face of their future husband would appear in the mirror. However, if they were destined to die before marriage, a skull would appear. The custom was widespread enough to be commemorated on greeting cards from the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The telling of ghost stories and viewing of horror films are common fixtures of Halloween parties. Episodes of TV series and specials with Halloween themes (with the specials usually aimed at children) are commonly aired on or before the holiday, while new horror films, are often released theatrically before the holiday to take advantage of the atmosphere.

Foods

Because the holiday comes in the wake of the annual apple harvest, candy apples (also known as toffee, caramel or taffy apples) are a common Halloween treat made by rolling whole apples in a sticky sugar syrup, sometimes followed by rolling them in nuts.

At one time, candy apples were commonly given to children, but the practice rapidly waned in the wake of widespread rumors that some individuals were embedding items like pins and razor blades in the apples. While these incidents are quite rare, many parents assumed that such heinous practices were rampant. At the peak of the hysteria, some hospitals offered free x-rays of children's Halloween hauls in order to find evidence of tampering. Virtually all of the few known candy poisoning incidents involved parents who poisoned their own children's candy, and there have been occasional reports of children putting needles in their own (and other children's) candy in need of a bit of attention.

Other foods associated with the holiday: candy corn; Báirín Breac (Ireland); colcannon (Ireland); bonfire toffee (UK); apple cider; cider; roasted sweetcorn; popcorn; roasted pumpkin seeds; pumpkin pie and pumpkin bread; "fun-sized" or individually wrapped pieces of small candy, typically in Halloween colors of orange, and brown/black; novelty candy shaped like skulls, pumpkins, bats, worms, etc.; small bags of potato chips, pretzels, and caramel corn; chocolates, caramels, and gum; and nuts.

Haunted attractions

Haunted attractions are entertainment venues designed to thrill and scare patrons; most are seasonal Halloween businesses. Origins of these paid scare venues are difficult to pinpoint, but it is generally accepted that they were first commonly used by the Jaycees for fundraising. They include haunted houses, corn mazes, and hayrides, and the level of sophistication of the effects has risen as the industry has grown. This increase in interest has led to more highly technical special effects and costuming that is comparable with that in Hollywood films. Common motifs for Halloween are settings resembling a cemetery, a haunted house, a hospital, or a specific monster-driven theme built around famous creatures or characters.

Typical elements of decoration include jack-o'-lanterns, fake spiders and cobwebs, and artificial gravestones and coffins. Coffins can be built to contain bodies or skeletons, and are sometimes rigged with animatronic equipment and motion detectors so that they will spring open in reaction to passers-by. Eerie music and sound effects are often played over loudspeakers to add to the atmosphere. Haunts can also be given a more "professional" look, now that such items as fog machines and strobe lights have become available for more affordable prices at discount retailers. Some haunted houses issue flashlights with dying batteries to attendees to enhance the feeling of unease.

Commercialization

Commercialization of Halloween in the United States began perhaps with Halloween postcards (featuring hundreds of designs), which were most popular between 1905 and 1915. Dennison Manufacturing Company (which published its first Halloween catalog in 1909) and the Beistle Company were pioneers in commercially made Halloween decorations, particularly die-cut paper items. German manufacturers specialized in Halloween figurines that were exported to the United States in the period between the two World Wars. Mass-produced Halloween costumes did not appear in stores until the 1930s, and trick-or-treating did not become a fixture of the holiday until the 1950s.

In the 1990s, many manufacturers began producing a larger variety of Halloween yard decorations; before this, the majority of decorations were homemade. Some of the most popular yard decorations are jack-o'-lanterns, scarecrows, witches, orange string-lights; inflatable decorations such as spiders, pumpkins, mummies, vampires; and animatronic window and door decorations. Other popular decorations are foam tombstones and gargoyles.

Halloween is now the United States' second-most popular holiday (after Christmas) for decorating; the sale of candy and costumes is also extremely common during the holiday, which is marketed to children and adults alike. Each year, popular costumes are dictated by various current events and pop-culture icons. On many college campuses, Halloween is a major celebration, with the Friday and Saturday nearest October 31 hosting many costume parties.

In many towns and cities, trick-or-treaters are welcomed by lit porch lights and jack-o'-lanterns. In some large and/or crime ridden areas, however, trick-or-treating is discouraged, or refocused to staged trick-or-treating events within nearby shopping malls, in order to prevent potential acts of violence against trick-or-treaters. Even where crime is not an issue, many American towns have designated specific hours for trick-or-treating to discourage late-night trick-or-treating.

Trick-or-treating may often end by early evening, but the nightlife thrives in many urban areas. Halloween costume parties provide an opportunity for adults to gather and socialize. Urban bars are frequented by people wearing Halloween masks and risqué costumes. Many bars and restaurants hold costume contests to attract customers to their establishments.

Several cities host Halloween parades. Anoka, Minnesota, the self-proclaimed "Halloween Capital of the World," celebrates the holiday with a large civic parade and several other city-wide events. Salem, Massachusetts, also has laid claim to the "Halloween Capital" title, while trying to dissociate itself from its history of persecuting witchcraft. New York City hosts the United States' largest Halloween celebration, started by Greenwich Village mask-maker Ralph Lee in 1973, the evening parade now attracts over two million spectators and participants, as well as roughly four-million television viewers annually. It is the largest participatory parade in the country if not the world, encouraging spectators to march in the parade as well.

Religious perspectives

In North America, Christian attitudes towards Halloween are quite diverse. In the Anglican Church, some dioceses have chosen to emphasize the Christian traditions of All Saints Day, while some other Protestants celebrate the holiday as Reformation Day, a day of remembrance and prayers for unity. Celtic Christians may have Samhain services that focus on the cultural aspects of the holiday, in the belief that many ancient Celtic customs are:

incompatible with the new Christian religion. Christianity embraced the Celtic notions of family, community, the bond among all people, and respect for the dead. Throughout the centuries, pagan and Christian beliefs intertwine in a gallimaufry (hodgepodge) of celebrations from October 31 through November 5, all of which appear both to challenge the ascendancy of the dark and to revel in its mystery.[17]

Many Christians ascribe no negative significance to Halloween, treating it as a purely secular holiday devoted to celebrating “imaginary spooks” and handing out candy. Halloween celebrations are common among Roman Catholic parochial schools throughout North America and in Ireland. In fact, the Roman Catholic Church sees Halloween as having a Christian connection.[18] Father Gabriele Amorth, a Vatican-appointed exorcist in Rome, has said, "[I]f English and American children like to dress up as witches and devils on one night of the year that is not a problem. If it is just a game, there is no harm in that."[19]

Most Christians hold the view that the tradition is far from being "satanic" in origin or practice, and that it holds no threat to the spiritual lives of children: being taught about death and mortality, and the ways of the Celtic ancestors actually being a valuable life lesson and a part of many of their parishioners' heritage. Other Christians, primarily of the Evangelical and Fundamentalist variety, are concerned about Halloween, and reject the holiday because they believe it trivializes (and celebrates) “the occult” and what they perceive as evil. A response among some fundamentalists in recent years has been the use of Hell houses or themed pamphlets (such as those of Jack T. Chick) which attempt to make use of Halloween as an opportunity for evangelism. Some consider Halloween to be completely incompatible with the Christian faith[20] due to its origin as a Pagan "festival of the dead." In more recent years, the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Boston has organized a "Saint Fest" on the holiday.

Many contemporary Protestant churches view Halloween as a fun event for children, holding events in their churches where children and their parents can dress up, play games, and get candy.

Religions other than Christianity also have varied views on Halloween. Some Wiccans feel that the tradition is offensive to "real witches" for promoting stereotypical caricatures of "wicked witches."

Halloween around the world

Halloween is not celebrated in all countries and regions of the world, but among those that do that traditions and importance of the celebration varies significantly. The celebrations in the United States have had a significant impact on how the holiday is observed in other nations. The history of Halloween traditions in a given country lends context to how it is presently celebrated.

In countries such as Japan, Germany, Italy, Spain, and some South American countries, Halloween has become popular in the context of American pop culture. Some Christians do not appreciate the resultant de-emphasis of the more spiritual aspects of All Hallows Eve and Reformation Day, respectively, or of regional festivals occurring around the same time (such as St Martin's Day or Guy Fawkes Night). Business has a natural tendency to capitalize on the holiday season's more commercial aspects, such as the sale of decorations and costumes.

United Kingdom

England

In parts of northern England, there is a traditional festival called Mischief Night, which falls on October 30. During the celebration, children play a range of "tricks" (ranging from minor to more serious) on adults. One of the more serious tricks might include the unhinging of garden gates (which were often thrown into ponds or moved far away). In recent years, such acts have occasionally escalated to extreme vandalism, sometimes involving street fires.

Halloween celebrations in England were popularized in the late-twentieth century under the pressure of American cultural influence, including a stream of films and television program aimed at children and adolescents and the discovery by retail experts of a marketing opportunity to fill the empty space before Christmas. This led to the introduction of practices such as pumpkin carving and trick-or-treat. One of the earliest references to trick or treating in Britain comes from a House of Lords debate in 1986, when it was described as a recently imported custom: the substance of the debate was the concern that youths were using trick or treating to obtain money from old people and others, or threatening nasty tricks. In England and Wales, trick-or-treating does still occur, although the practice is regarded by some as a nuisance, sometimes resulting in crimes.[21]

Ireland

Halloween is significant event in Ireland where it is widely celebrated. It is known in Irish as Oíche Shamhna (pronounced ee-hah how-nah), literally "Samhain Night." Pre-Christian Celts had an autumn festival, Samhain (pronounced /ˈsˠaunʲ/from the Old Irish ˈˈsamainˈˈ), "End of Summer," a pastoral and agricultural "fire festival" or feast, when the dead revisited the mortal world and large communal bonfires would hence be lit to ward off evil spirits.

On Halloween night, adults and children dress up as creatures from the underworld (ghosts, ghouls, zombies, witches, and goblins), light bonfires, and enjoy spectacular fireworks displays—in particular, the city of Derry is home to the largest organized Halloween celebration on the island, in the form of a street carnival and fireworks display. It is also common for fireworks to be set off for the entire month preceding Halloween as well as a few days after. Halloween was perceived as the night during which the division between the world of the living and the otherworld was blurred so that spirits of the dead and inhabitants from the underworld were able to walk free on the earth.

Houses are frequently adorned with pumpkins or turnips carved into scary faces; lights or candles are sometimes placed inside the carvings, resulting in an eerie effect. The traditional Halloween cake in Ireland is the barmbrack, which is a fruit bread. Games of divination are also played at Halloween, but are becoming less popular

Scotland

In Scotland, folklore, including that of Halloween, revolves around the ancient Celtic belief in faeries (Sidhe, or Sith, in modern Gaelic). Children who ventured out carried a traditional lantern (samhnag) with a devil face carved into it to frighten away the evil spirits. Such Halloween lanterns were made from a turnip, or “Neep” in “Lowland Scots,” with a candle lit in the hollow inside. In modern times, however, such lanterns use pumpkins, as in North American traditions, possibly because it is easier to carve a face into a pumpkin than into a turnip.

Houses were also protected with the same candle lanterns. If the spirits got past the protection of the lanterns, the Scottish custom was to offer the spirits parcels of food to leave and spare the house another year. Children, too, were given the added protection by disguising them as such creatures in order to blend in with the spirits. If children approached the door of a house, they were also given offerings of food (Halloween being a harvest festival), which served to ward off the potential spirits that may lurk among them. This is where the origin of the practice of Scottish “guising” (a word that comes from "disguising"), or going about in costume, arose. It is now a key feature of the tradition of trick-or-treating practiced in North America.

In modern-day Scotland, this old tradition survives, chiefly in the form of children going door to door "guising" in this manner; that is, dressed in a disguise (often as a witch, ghost, monster, or another supernatural being) and offering entertainment of various sorts. If the entertainment is enjoyed, the children are rewarded with gifts of sweets, fruits, or money.

Popular games played on the holiday include "dooking" for apples (retrieving an apple from a bucket of water using only one's mouth). In some places, the game has been replaced (because of fears of contracting saliva-borne illnesses in the water) by standing over the bowl holding a fork in one's mouth and releasing it in an attempt to skewer an apple using only gravity. Another popular game is attempting to eat, while blindfolded, a treacle—or jam-coated scone on a piece of string hanging from the ceiling. Sometimes the blindfold is left out, because it is already difficult to eat the scone. In all versions, however, the participants cannot use their hands.

Wales

In Wales, Halloween is known as Nos Calan Gaeaf (the beginning of the new winter; see Calan Gaeaf). Spirits are said to walk around (as it is an Ysbrydnos, or "spirit night"), and a "white lady" ghost is sometimes said to appear. Bonfires are lit on hillsides to mark the night.

Isle of Man

The Manx traditionally celebrate Hop-tu-Naa on October 31; this ancient Celtic tradition has parallels in Scottish and Irish traditions.

European Continent

The Netherlands

Halloween has become increasingly popular in The Netherlands since the early 1990s. From early October, stores are full of merchandising related to the popular Halloween themes. Students and little children dress up on Halloween for parties and small parades. Trick-or-treating is highly uncommon, also because this directly interferes with the Dutch tradition of celebrating St. Martin's Day. On November 11, Dutch children ring doorbells hoping to receive a small treat in return for singing a short song dedicated to St. Martin.

Romania

Halloween in Romania is celebrated around the myth of "Dracula" on October 31. In Transylvania and especially in the city of Sighişoara, there are many costume parties, for teenagers and adults, that are created from the U.S. model. Also the spirit of Dracula is believed to live there because the town was the site of many witch trials; these are recreated today by actors on the night of Halloween.[22]

Sweden

In Sweden All Hallows Eve (All Saint's Night, Alla Helgons Natt) is a Christian, public holiday which always falls on the first Saturday in November. It is about lighting candles at graves and remembering the dead. Besides Halloween Swedes also go trick-or-treating on Maundy Thursday.

When the American non-Christian Halloween was introduced in Sweden it was celebrated on the same day as All Hallows Eve. This is due to a misunderstanding when the retail business organizations introduced Halloween in the mid-1990s. Traditions such as trick-or-treating, masquerades and other typically American Halloween traditions are not that popular, and are especially disliked by older people as the holiday is supposed to be a day of remembering the dead.

Many Swedes are unaware that Halloween in the English-speaking countries is a non-Christian holiday celebrated on October 31. The entire holiday is seen as an American import, and people in general tend not to like typically American traditions. The old Swedish traditions, both Christian and pagan (asatro), are being forgotten and replaced by commercial American customs.

Switzerland

In Switzerland, Halloween is seen as being a pagan festival. After first becoming popular in 1999, Halloween is on the wane. People see it as an imported product from the United States, which has not recently enjoyed a good image in the country. Switzerland already has a "festival overload" and even though Swiss people like to dress up for any occasion, they do prefer a traditional element.

Ueli Mäder, a professor of sociology at Basel University said that the Swiss adoption of Halloween—Swiss shops stocked Halloween costumes and masks for the first time in 1999—came from "a need for rituals." "In a strongly commercialized world, a need arises for meaningful experiences. I can imagine that a ritual like Halloween when it is celebrated in a simple genuine way can satisfy that need." But he added: "It also took on an exaggerated or extreme form for a while which probably turned some people off. Perhaps is there is a need to bring Halloween back to a more simple level." [23]

Denmark

In Denmark children will go trick-or-treating on Halloween, despite collecting candy from neighbors on Fastelavn, Danish carnival. Fastelavn evolved from the Roman Catholic tradition of celebrating in the days before Lent, but after Denmark became a Protestant nation, the holiday became less specifically religious. This holiday occurs seven weeks before Easter Sunday and is sometimes described as a Nordic Halloween, with children dressing up in costumes and gathering treats for the Fastelavn feast.

Italy

In the traditional culture of some regions of Italy, especially in the North of the country—populated by Celts before the arrive of Romans—there were until the last century traditions very similar to Halloween, i.e. beliefs about nocturnal visiting and processions of dead people and the use of preparing special biscuits and carving jack-o'-lanterns. These traditions were going to vanishing completely when the feast of Halloween arrived in a new form from America.

Eastern Europe

Halloween is uncelebrated in eastern Europe.

Other regions

Carribean

The Island Territory of Bonaire is one of five islands of the Netherlands Antilles, accordingly a part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. As such, customs found in Europe as well as the United States are common, including the celebration of Halloween. Children often dress up in costume for trick-or-treating expecting to receive candy.

Mexico

In Mexico, Halloween has been celebrated since roughly 1960. There, celebrations have been influenced by the American traditions, such as the costuming of children who visit the houses of their neighbourhood in search of candy. Though the "trick-or-treat" motif is used, tricks are not generally played on residents not providing candy. Older crowds of preteens, teenagers and adults will sometimes organize Halloween-themed parties, which might be scheduled on the nearest available weekend. Usually kids stop by at peoples' houses, knock on their door or the ring the bell and say "¡Noche de Brujas, Halloween!" ('Witches' Night—Halloween!') or "¡Queremos Haloween!" (We want Halloween!). The second phrase is more commonly used among children, the afirmation of "We want Halloween" means "We want candy."

Halloween in Mexico begins three days of consecutive holidays, as it is followed by All Saints' Day, which also marks the beginning of the two day celebration of the Day of the Dead or the Día de los Muertos. This might account for the initial explanations of the holiday having a traditional Mexican-Catholic slant.

Canada

In Western Canada, fireworks displays and a civic bonfire are part of the festivities.

Australia and New Zealand

Halloween has gained little recognition in Australia and New Zealand, and that largely through American media influences (primarily sit-coms but also with the Simpsons Halloween Specials), with few families in Australia celebrating the tradition. On Halloween night, horror films and horror-themed TV episodes are traditionally aired, and currently, Halloween private parties are more commonly held than actual "trick-or-treating," however both are still observed. Trick or treating is generally only done in the trick-or-treater's neighborhood.

Notes

- ↑ Nicholas Rogers, "Samhain and the Celtic Origins of Halloween," Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), 11-21.

- ↑ Simpson, John and Weiner, Edmund (1989). Oxford English Dictionary, second, London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861186-2. OCLC 17648714.

- ↑ History of the Jack O'Lantern, Pumpkin Nook

- ↑ Act 2, Scene 1.

- ↑ Ruth Edna Kelley, The Book of Hallowe'en, Boston: Lothrop, Lee and Shepard Co., 1919, chapter 15, "Hallowe'en in America."

- ↑ For examples, see the websites Postcard & Greeting Card Museum: Halloween Gallery, Antique Hallowe'en Postcards, Vintage Halloween Postcards, and Morticia's Morgue Antique Halloween Postcards.

- ↑ Rogers, p. 76.

- ↑ Theo. E. Wright, "A Halloween Story," St. Nicholas, October 1915, p. 1144. Mae McGuire Telford, "What Shall We Do Halloween?" Ladies Home Journal, October 1920, p. 135.

- ↑ "'Trick or Treat' Is Demand," Herald (Lethbridge, Alberta), November 4, 1927, p. 5, dateline Blackie, Alberta, Nov. 3.

- ↑ "Halloween Pranks Keep Police on Hop," Oregon Journal (Portland, Oregon), November 1, 1934:

"The Gangsters of Tomorrow," The Helena Independent (Helena, Montana), November 2, 1934, p. 4:Other young goblins and ghosts, employing modern shakedown methods, successfully worked the "trick or treat" system in all parts of the city.

The Chicago Tribune also mentioned door-to-door begging in Aurora, Illinois on Halloween in 1934, although not by the term "trick-or-treating." "Front Views and Profiles" (column), Chicago Tribune, Nov. 3, 1934, p. 17.Pretty Boy John Doe rang the door bells and his gang waited his signal. It was his plan to proceed cautiously at first and give a citizen every opportunity to comply with his demands before pulling any rough stuff. "Madam, we are here for the usual purpose, 'trick or treat.'" This is the old demand of the little people who go out to have some innocent fun. Many women have some apples, cookies or doughnuts for them, but they call rather early and the "treat" is given out gladly.

- ↑ Doris Hudson Moss, "A Victim of the Window-Soaping Brigade?" The American Home, November 1939, p. 48. Moss was a California-based writer.

- ↑ The Historical Newspaper Collection at Ancestry.com indexes more than 16 million pages from over 1,000 different newspapers across the U.S, U.K. and Canada dating back to the 1700s.

- ↑ Published in Indianapolis, Indiana and Chicago, Illinois, respectively.

- ↑ The Baby Snooks Show, November 1, 1946, and The Jack Benny Show, October 31, 1948, both originating from NBC Radio City in Hollywood; and The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet, October 31, 1948, originating from CBS Columbia Square in Hollywood.

- ↑ "Halloween Party," The Adventures of Ozzie & Harriet, Oct. 31, 1952.

- ↑ "A Barrel of Fun for Halloween Night," Parents Magazine, October 1953, p. 140. "They're Changing Halloween from a Pest to a Project," The Saturday Evening Post, October 12, 1957, p. 10.

- ↑ "Feast of Samhain/Celtic New Year/Celebration of All Celtic Saints November 1," All Saints Parish. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ↑ Halloween’s Christian Roots AmericanCatholic.org. Retrieved on October 24, 2007.

- ↑ Gyles Brandreth, "The Devil is gaining ground" The Sunday Telegraph (London), March 11, 2000.

- ↑ “Trick?” or “Treat?”—Unmasking Halloween (HTML). The Restored Church of God (n.d.). Retrieved 2007-09-21.

- ↑ BBC, "Fines for Halloween troublemakers," BBC News, November 28, 2006. Retrieved February 21, 2009.

- ↑ Halloween in Transylvania, Romania

- ↑ Halloween retailers get a shock

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Diane C. Arkins, Halloween: Romantic Art and Customs of Yesteryear, Pelican Publishing Company (2000). 96 pages. ISBN 1-56554-712-8

- Diane C. Arkins, Halloween Merrymaking: An Illustrated Celebration Of Fun, Food, And Frolics From Halloweens Past, Pelican Publishing Company (2004). 112 pages. ISBN 1-58980-113-X

- Lesley Bannatyne, Halloween: An American Holiday, An American History, Facts on File (1990, Pelican Publishing Company, 1998). 180 pages. ISBN 1-56554-346-7

- Lesley Bannatyne, A Halloween Reader. Stories, Poems and Plays from Halloweens Past, Pelican Publishing Company (2004). 272 pages. ISBN 1-58980-176-8

- Phyllis Galembo, Dressed for Thrills: 100 Years of Halloween Costumes and Masquerade, Harry N. Abrams, Inc. (2002). 128 pages. ISBN 0-8109-3291-1

- Lint Hatcher, The Magic Eightball Test: A Christian Defense of Halloween and All Things Spooky, Lulu.com (2006). ISBN 978-1847287564

- Ronald Hutton, Stations of the Sun: A History of the Ritual Year in Britain, Oxford Paperbacks (2001). 560 pages. ISBN 0-19-285448-8

- Jean Markale, The Pagan Mysteries of Halloween: Celebrating the Dark Half of the Year (translation of Halloween, histoire et traditions), Inner Traditions (2001). 160 pages. ISBN 0-89281-900-6

- Lisa Morton, The Halloween Encyclopedia, McFarland & Company (2003). 240 pages. ISBN 0-7864-1524-X

- Nicholas Rogers, Halloween: From Pagan Ritual to Party Night, Oxford University Press (2002). 198 pages. ISBN 0-19-514691-3

- Jack Santino (ed.), Halloween and Other Festivals of Death and Life, University of Tennessee Press (1994). 280 pages. ISBN 0-87049-813-4

- David J. Skal, Death Makes A Holiday: A Cultural History of Halloween, Bloomsbury USA (2003). 224 pages. ISBN 1-58234-305-5

- Ben Truwe, The Halloween Catalog Collection. Portland, Oregon: Talky Tina Press (2003). ISBN 0-9703448-5-6.

External links

- Halloween Treats

- Feast of Samhain/Celtic New Year/Celebration of All Celtic Saints—Celtic Christianity

- Samhain: Season of Death and Renewal—Celtic Studies, Gaelic culture and religion

- Halloween at the Open Directory Project

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.