Christmas

Christmas or Christmas Day commemorates and celebrates the birth of Jesus. The word Christmas is derived from Middle English Christemasse and from Old English Cristes mĂŚsse.[1] It is a contraction meaning "Christ's mass." The name of the holiday is sometimes shortened to Xmas because Roman letter "X" resembles the Greek letter Χ (chi), an abbreviation for Christ (ΧĎΚĎĎĎĎ).

Christmas in the West is traditionally observed on December 25, or January 7 in the Eastern Orthodox Churches. In most Christian communities, the holiday is celebrated with great cheer, song, exchange of gifts, storytelling and family gatherings. The popularity of Christmas is due in large part to the "spirit of Christmas," a spirit of charity expressed through gift-giving and acts of kindness that celebrate the human heart of the Christian message.

Besides its Christian roots, many Christmas traditions have their origins in pagan winter celebrations. Examples of winter festivals that have influenced Christmas include the pre-Christian festivals of Yule, and Roman Saturnalia.[2]

While Christmas began as a religious holiday, it has appropriated many secular characteristics over time, including many variations of the Santa Claus myth, decoration and display of the Christmas tree, and other aspects of consumer culture. Many distinct regional traditions of Christmas are still practiced around the world, despite the widespread influence of Anglo-American Christmas motifs disseminated in popular culture.

History

Origins of the holiday

The historical development of Christmas is quite fascinating. According to the Bible, Jesus' birth was celebrated by many well-wishers including the Magi who came bearing gifts. The early Christians in the Roman Empire wished to continue this practice but found that celebrating Jesus' birth was very dangerous under Roman rule, where being a Christian could be punishable by death. Thus, Christians began to celebrate Christâs birthday on December 25, which was already an important pagan festival, in order to safely adapt to Roman customs while still honoring Jesus' birth.

This is how Christmas came to be celebrated on the Roman holiday of Saturnalia, and it was from the pagan holiday that many of the customs of Christmas had their roots. The celebrations of Saturnalia included the making and giving of small presents (saturnalia et sigillaricia). This holiday was observed over a series of days beginning on December 17 (the birthday of Saturn), and ending on December 25 (the birthday of Sol Invictus, the "Unconquered Sun"). The combined festivals resulted in an extended winter holiday season. Business was postponed and even slaves feasted. There was drinking, gambling and singing, and nudity was relatively common. It was the "best of days," according to the poet Catullus.[3]

The feast of Sol Invictus on December 25 was a sacred day in the religion of Mithraism, which was widespread in the Roman Empire. Its god, Mithras, was a solar deity of Persian origin, identified with the Sun. It displayed its unconquerability as "Sol Invictus" when it began to rise higher in the sky following the Winter Solsticeâhence December 25 was celebrated as the Sun's birthday. In 274 C.E., Emperor Aurelian officially designated December 25 as the festival of Sol Invictus.

Evidence that early Christians were observing December 25 as Jesus' birthday comes from Sextus Julius Africanus's book Chronographiai (221 C.E.), an early reference book for Christians. Yet from the first, identification of Christ's birth with a pagan holiday was controversial. The theologian Origen, writing in 245 C.E., denounced the idea of celebrating the birthday of Jesus "as if he were a king pharaoh." Thus Christmas was celebrated with a mixture of Christian and secular customs from the beginning, and remains so to this day.

Furthermore, in the opinion of many theologians, there was little basis for celebrating Christ's birth in December. Around 220 C.E., Tertullian declared that Jesus died on March 25. Although scholars no longer accept this as the most likely date for the crucifixion, it does suggest that the 25th day of the monthâMarch 25 being nine months before December 25thâhad significance for the church even before it was used as a basis to calculate Christmas. Modern scholars favor a crucifixion date of April 3, 33 C.E. (These are Julian calendar dates. Subtract two days for a Gregorian date), the date of a partial lunar eclipse.[4] By 240 C.E., a list of significant events was being assigned to March 25, partly because it was believed to be the date of the vernal equinox. These events include the creation, the fall of Adam, and, most relevantly, the Incarnation.[5] The view that the Incarnation occurred on the same date as crucifixion is consistent with a Jewish belief that prophets died at an "integral age," either an anniversary of their birth or of their conception.[6][7]

Impetus for the celebration of Christmas increased after Constantius, son of Emperor Constantine, decreed that all non-Christian temples in the empire be immediately closed and anyone who still offered sacrifices of worship to the gods and goddesses in these temples was to be put to death. The followers of Mithras were eventually forced to convert under these laws. In spite of their conversion, they adapted many elements of their old religions into Christianity. Among these, was the celebration of the birth of Mithras on December 25, which was now observed as the birthday of Jesus.

Another impetus for official Roman support for Christmas grew out of the Christological debates at the time of Constantine. The Alexandrian school argued that he was the divine word made flesh (see John 1:14), while the Antioch school held that he was born human and infused with the Holy Spirit at the time of his baptism (see Mark 1:9-11). A feast celebrating Christ's birth gave the church an opportunity to promote the intermediate view that Christ was divine from the time of his incarnation.[8] Mary, a minor figure for early Christians, gained prominence as the theotokos, or god-bearer. There were Christmas celebrations in Rome as early as 336 C.E. December 25 was added to the calendar as a feast day in 350 C.E.[8]

Christmas soon outgrew the Christological controversy that created it and came to dominate the Medieval calendar.

The 40 days before Christmas became the "forty days of Saint Martin," now Advent. Former Saturnalian traditions were attached to Advent. Around the twelfth century, these traditions transferred again to the "twelve days of Christmas" (i.e., Christmas to Epiphany).[8]

The fortieth day after Christmas was Candlemas. The Egyptian Christmas celebration on January 6 was adopted as Epiphany, one of the most prominent holidays of the year during Early Middle Ages. Christmas Day itself was a relatively minor holiday, although its prominence gradually increased after Charlemagne was crowned on Christmas Day in 800 C.E.

Northern Europe was the last part to Christianize, and its pagan celebrations had a major influence on Christmas. Scandinavians still call Christmas Jul (Yule or Yultid), originally the name of a 12-day pre-Christian winter festival. Logs were lit to honor Thor, the god of thunder, hence the "Yule log." In Germany, the equivalent holiday is called Mitwinternacht (mid-winter night). There are also 12 Rauhnächte (harsh or wild nights).[9]

By the High Middle Ages, Christmas had become so prominent that chroniclers routinely noted where various magnates "celebrated Christmas." King Richard II of England hosted a Christmas feast in 1377 at which 28 oxen and three hundred sheep were eaten.[8] The "Yule boar" was a common feature of Medieval Christmas feasts. Caroling also became popular. Various writers of the time condemned caroling as lewd (largely due to overtones reminiscent of the traditions of Saturnalia and Yule).[8] "Misrule"âdrunkenness, promiscuity, gamblingâwas also an important aspect of the festival. In England, gifts were exchanged on New Year's Day, and there was special Christmas ale.[8]

The Reformation and modern times

During the Reformation, Protestants condemned Christmas celebration as "trappings of popery" and the "rags of the Beast." The Catholic Church responded by promoting the festival in a more religiously oriented form. When a Puritan parliament triumphed over the King, Charles I of England (1644), Christmas was officially banned (1647). Pro-Christmas rioting broke out in several cities. For several weeks, Canterbury was controlled by the rioters, who decorated doorways with holly and shouted royalist slogans.[10] The Restoration (1660) ended the ban, but Christmas celebration was still disapproved of by the Anglican clergy.

By the 1820s, sectarian tension had eased and British writers began to worry that Christmas was dying out. They imagined Tudor Christmas as a time of heartfelt celebration, and efforts were made to revive the holiday. Prince Albert, from Bavaria, married Queen Victoria in 1840, introducing the German tradition of the 'Christmas tree' into Windsor castle in 1841. The book A Christmas Carol (1843) by Charles Dickens played a major role in reinventing Christmas as a holiday emphasizing family, goodwill, and compassion (as opposed to communal celebration and hedonistic excess).[11]

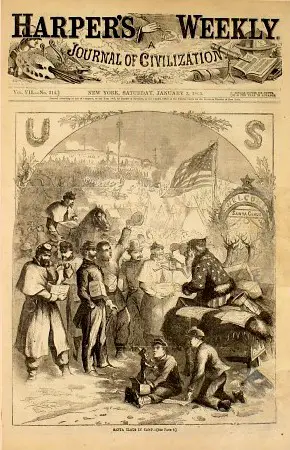

The Puritans of New England disapproved of Christmas and celebration was outlawed in Boston (1659-1681). Meanwhile, Christians in Virginia and New York celebrated freely. Christmas fell out of favor in the U.S. after the American Revolution, when it was considered an "English custom." Interest was revived by several short stories by Washington Irving in The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon (1819) and by "Old Christmas" (1850) which depict harmonious warm-hearted holiday traditions Irving claimed to have observed in England. Although some argue that Irving invented the traditions he describes, they were imitated by his American readers. German immigrants and the homecomings of the Civil War helped promote the holiday. Christmas was declared a federal holiday in the United States in 1870.

Washington Irving, in his fake book purportedly written by by a man named Diedrich Knickerbocker, wrote of Saint Nicholas "riding over the tops of the trees, in that selfsame waggon wherein he brings his yearly presents to children."[13] The connection between Santa Claus and Christmas was popularized by the poem "A Visit from Saint Nicholas" (1822) by Clement Clarke Moore, which depicts Santa driving a sleigh pulled by reindeer and distributing gifts to children. His image was created by German-American cartoonist Thomas Nast (1840-1902), who drew a new image annually beginning in 1863.[14] By the 1880s, Nast's Santa had evolved into the form we now recognize. The image was popularized by advertisers in the early twentieth century.[15]

In the midst of World War I, there was a Christmas truce between German and British troops in France (1914). Soldiers on both sides spontaneously began to sing Christmas carols and stopped fighting. The truce began on Christmas Day and continued for some time afterward. There was even a soccer game between the trench lines in which Germany's 133rd Royal Saxon Regiment is said to have bested Britain's Seaforth Highlanders 3-2.

The Nativity

According to tradition, Jesus was born in the town of Bethlehem in a stable, surrounded by farm animals and shepherds, and Jesus was born into a manger from the Virgin Mary assisted by her husband Joseph.

Remembering or re-creating the Nativity (the birth of Jesus) is one of the central ways that Christians celebrate Christmas. For example, the Eastern Orthodox Church practices the Nativity Fast in anticipation of the birth of Jesus, while the Roman Catholic Church celebrates Advent. In some Christian churches, children often perform plays re-creating the events of the Nativity, or sing some of the numerous Christmas carols that reference the event. Many Christians also display a small re-creation of the Nativity known as a crèche or Nativity scene in their homes, using small figurines to portray the key characters of the event. Live Nativity scenes are also re-enacted using human actors and live animals to portray the event with more realism.

Economics of Christmas

Christmas has become the greatest annual economic stimulus for many nations. Sales increase dramatically in almost all retail areas and shops introduce new merchandise as people purchase gifts, decorations, and supplies. In the United States, the Christmas shopping season generally begins on "Black Friday," the day after Thanksgiving, celebrated in the United States on the third Thursday of November. "Black" refers to turning a profit, as opposed to the store being "in the red." Many stores begin stocking and selling Christmas items in October/November (and in the UK, even September/October).

More businesses and stores close on Christmas Day than any other day of the year. In the United Kingdom, the Christmas Day (Trading) Act 2004 prevents all large shops from trading on Christmas Day.

Most economists agree, however, that Christmas produces a deadweight loss under orthodox microeconomic theory, due to the surge in gift-giving. This loss is calculated as the difference between what the gift giver spent on the item and what the gift receiver would have paid for the item. It is estimated that in 2001 Christmas resulted in a $4 billion deadweight loss in the U.S. alone.[16] Because of complicating factors, this analysis is sometimes used to discuss possible flaws in current microeconomic theory.

In North America, film studios release many high-budget movies in the holiday season, including Christmas theme films, fantasy movies, or high-tone dramas with rich production values.

Santa Claus and other bringers of gifts

In Western culture, the holiday is characterized by the exchange of gifts among friends and family members, some of the gifts being attributed to Santa Claus (also known as Father Christmas, Saint Nicholas, Saint Basil and Father Frost).

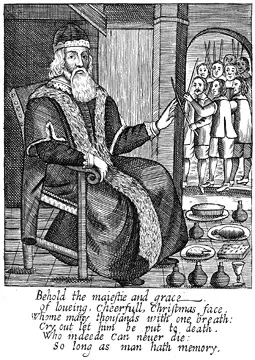

Father Christmas predates the Santa Claus character, and was first recorded in the fifteenth century,[17] but was associated with holiday merrymaking and drunkenness. Santa Claus is a variation of a Dutch folk tale based on the historical figure Saint Nicholas, or Sinterklaas, who gave gifts on the eve of his feast day of December 6. He became associated with Christmas in nineteenth century America and was renamed Santa Claus or Saint Nick. In Victorian Britain, Father Christmas's image was remade to match that of Santa. The French equivalent of Santa, Père NoÍl, evolved along similar lines, eventually adopting the Santa image.

In some cultures Santa Claus is accompanied by Knecht Ruprecht, or Black Peter. In other versions, elves make the holiday toys. His wife is referred to as Mrs. Claus.

The current tradition in several Latin American countries (such as Venezuela) holds that while Santa makes the toys, he then gives them to the Baby Jesus, who is the one who actually delivers them to the children's homes. This story is meant to be a reconciliation between traditional religious beliefs and modern day globalization, most notably the iconography of Santa Claus imported from the United States.

The Christmas Tree

The Christmas tree is often explained as a Christianization of the ancient pagan idea that evergreen trees like, pine and juniper, symbolize hope and anticipation of a return of spring, and the renewal of life. The phrase "Christmas tree" is first recorded in 1835 and represents the importation of a tradition from Germany, where such trees became popular in the late eighteenth century.[17] Christmas trees may be decorated with lights and ornaments.

Since the nineteenth century, the poinsettia (Euphorbia pulcherrima), an indigenous flowering plant from Mexico, has been associated with Christmas. Other popular holiday plants include holly, red amaryllis, and Christmas cactus (Zygocactus), all featuring the brilliant combination of red and green.

Along with a Christmas tree, the interior of a home may be decorated with garlands, wreaths, and evergreen foliage, particularly holly (Ilex aquifolium or Ilex opaca) and mistletoe (Phoradendron flavescens or Viscum album). In Australia, North and South America, and to a lesser extent Europe, it is traditional to decorate the outside of houses with lights and sometimes with illuminated sleighs, snowmen, and other Christmas figures.

Municipalities often sponsor decorations as well. Christmas banners may be hung from street lights and Christmas trees placed in the town square. While some decorations such as a tree are considered secular in many parts of the world, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia bans such displays as symbols of Christianity.

In the Western world, rolls of brightly colored paper with secular or religious Christmas motifs are manufactured for the purpose of wrapping gifts.

Regional customs and celebrations

Christmas celebrations include a great number and variety of customs with either secular, religious, or national aspects, which vary from country to country:

After the Russian Revolution, Christmas celebration was banned in that country from 1917 until 1992.

Several Christian denominations, notably the Jehovah's Witnesses, Puritans, and some fundamentalists, view Christmas as a pagan holiday not sanctioned by the Bible.

In the Southern Hemisphere, Christmas is during the summer. This clashes with the traditional winter iconography, resulting in oddities such as a red fur-coated Santa Claus surfing in for a turkey barbecue on Australia's Bondi Beach.

Japan has adopted Santa Claus for its secular Christmas celebration, but New Year's Day is a far more important holiday.

In India, Christmas is often called bada din ("the big day"), and celebration revolves around Santa Claus and shopping.

In South Korea, Christmas is celebrated as an official holiday.

In the Netherlands, Saint Nicholas' Day (December 6) remains the principal day for gift giving while Christmas Day is a more religious holiday.

In much of Germany, children put shoes out on window sills on the night of December 5, and find them filled with candy and small gifts the next morning. The main day for gift giving in Germany is December 24, when gifts are brought by Santa Claus or are placed under the Christmas tree.

In Poland, Santa Claus (Polish: ĹwiÄty MikoĹaj) gives gifts on two occasions: on the night of December 5 (so that children find them on the morning of December 6, (Saint Nicholas Day) and on Christmas Eve (so that children find gifts that same day).

In Hungary, Santa Claus (Hungarian: MikulĂĄs) or for non-religious people Father Winter (Hungarian: TĂŠlapĂł) is often accompanied by a black creature called Krampusz.

In Spain, gifts are brought by the Magi on Epiphany (January 6), although the tradition of leaving gifts under the Christmas Tree on Christmas Eve (December 24) for the children to find and open the following morning has been widely adopted as well. Elaborate "Nacimiento" nativity scenes are common, and a midnight meal is eaten on Noche-Buena, the good night, Christmas Eve.

In Russia, Grandfather Frost brings presents on New Year's Eve, and these are opened on the same night. The patron saint of Russia is Saint Nicola, the Wonder Worker, in the Orthodox tradition, whose Feast Day is celebrated December 6.

In Scotland, presents were traditionally given on Hogmanay, which is New Year's Eve. However, since the establishment of Christmas Day as a legal holiday in 1967, many Scots have adopted the tradition of exchanging gifts on Christmas morning.

The Declaration of Christmas Peace has been a tradition in Finland since the Middle Ages. It takes place in the Old Great Square of Turku, Finland's official Christmas City and former capital.

Social aspects and entertainment

In many countries, businesses, schools, and communities have Christmas celebrations and performances in the weeks before Christmas. Christmas pageants may include a retelling of the story of the birth of Christ. Groups visit neighborhood homes, hospitals, or nursing homes, to sing Christmas carols. Others do volunteer work or hold fundraising drives for charities.

On Christmas Day or Christmas Eve, a special meal is usually served. In some regions, particularly in Eastern Europe, these family feasts are preceded by a period of fasting. Candy and treats are also part of Christmas celebration in many countries.

Another tradition is for people to send Christmas cards, first popularized in London in 1842, to friends and family members. Cards are also produced with secular generic messages such as "season's greetings" or "happy holidays," as a gesture of inclusiveness for senders and recipients who prefer to avoid the religious sentiments and symbolism of Christmas, yet still participate in the gaiety of the season.

Christmas in the arts and media

Many fictional Christmas stories capture the spirit of Christmas in a modern-day fairy tale, often with heart-touching stories of a Christmas miracle. Several have become part of the Christmas tradition in their countries of origin.

Among the most popular are Tchaikovsky's ballet The Nutcracker based on the story by German author E.T.A. Hoffman, and Charles Dickens' novel A Christmas Carol. The Nutcracker tells of a nutcracker that comes to life in a young German girl's dream. Charles Dickens' A Christmas Carol is the tale of the rich and miserly curmudgeon Ebenezer Scrooge. Scrooge rejects compassion, philanthropy, and Christmas until he is visited by the ghosts of Christmas Past, Present and Future, who show him the consequences of his ways.

Some Scandinavian Christmas stories are less cheery than Dickens'. In H. C. Andersen's The Little Match Girl, a destitute little girl walks barefoot through snow-covered streets on Christmas Eve, trying in vain to sell her matches, and peeking in at the celebrations in the homes of the more fortunate.

In 1881, the Swedish magazine Ny Illustrerad Tidning published Viktor Rydberg's poem Tomten featuring the first painting by Jenny NystrĂśm of the traditional Swedish mythical character tomte, which she turned into the friendly white-bearded figure and associated with Christmas.

Many Christmas stories have been popularized as movies and television specials. A notable example is the classic Hollywood film It's a Wonderful Life. Its hero, George Bailey, is a businessman who sacrificed his dreams to help his community. On Christmas Eve, a guardian angel finds him in despair and prevents him from committing suicide by magically showing him how much he meant to the world around him.

A few true stories have also become enduring Christmas tales themselves. The story behind the Christmas carol Silent Night, and the editorial by Francis P. Church Yes, Virginia, there is a Santa Claus first published in The New York Sun in 1897, are among the most well-known of these.

Radio and television programs aggressively pursue entertainment and ratings through their cultivation of Christmas themes. Radio stations broadcast Christmas carols and Christmas songs, including classical music such as the "Hallelujah chorus" from Handel's Messiah. Among other classical pieces inspired by Christmas are the Nutcracker Suite, adapted from Tchaikovsky's ballet score, and Johann Sebastian Bach's Christmas Oratorio (BWV 248). Television networks add Christmas themes to their standard programming, run traditional holiday movies, and produce a variety of Christmas specials.

Notes

- â "Christmas", The Catholic Encyclopedia, 1913. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â The Magical History Of Yule, The Pagan Winter Solstice Celebration The Huffington Post, December 22, 2016. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â Julilla Sempronia, Ancient Voices: Saturnalia, AncientWorlds 2004. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â Sten Odenwald, Can you date the crucifixion of Jesus Christ using astronomy? 1997. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â Frederick Holweck, The Feast of the Annunciation Catholic Encyclopedia, 1907 ed. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â Louis Duchesne, Les origines du culte chrĂŠtien: Etude sur la liturgie latine avant Charlemagne (Paris, 1889).

- â Thomas J. Talley, Origins of the Liturgical Year (New York: Pueblo Publishing Company, 1991).

- â 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Alexander Murray, Medieval Christmas History Today 36(12) (December 1986): 31-39. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â Dahna Barnett, Midwinter Traditions Mythic Passages, December 2006. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â Chris Durston, Lords of Misrule: The Puritan War on Christmas 1642-60 History Today 35(12) (December 1985): 7-14. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â Geoffrey Rowell, Dickens and the Construction of Christmas History Today 43(12) (December 1993): 17-24. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â The Examination and Tryal of Old Father Christmas hymnsandcarolsofchristmas. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â Washington Irving, A History of New York (Penguin Classics, 2008, ISBN 0143105612).

- â Sam Ursu, The Weird History of Christmas in America December 20, 2017. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â David Mikkelson, Did Coca-Cola Invent the Modern Image of Santa Claus? Snopes.com. December 18, 2001. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â Is Santa a deadweight loss? The Economist, December 20, 2001. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

- â 17.0 17.1 Douglas Harper, Christ, Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved July 17, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Duchesne, Louis. Origines Du Culte Chretien: Etude Sur La Liturgie Latine Avant Charlemagne. Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 1148818758

- Heindel, Max. Mystical Interpretation of Christmas. Holos Arts Project Publishing Company, 1920. ISBN 0911274650

- Irving, Washington. A History of New York. Penguin Classics, 2008. ISBN 0143105612

- Nissenbaum, Stephen. The Battle for Christmas: A Social and Cultural History of Our Most Cherished Holiday. Vintage, 1997. ISBN 0679740384

- Restad, Penne L., Christmas in America: A History. New York, Oxford University Press. 1995. ISBN 0195093003

- Talley, Thomas J. The Origins Of The Liturgical Year. Pueblo Books, 1991. ISBN 0814660754

External Links

All links retrieved December 10, 2023.

- Christmas: The Curious Origins of a Popular Holiday

- Christmas Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- Christmas in India

| |||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.