Rodent

| Rodents

| ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

White-tailed Antelope Squirrel, Ammospermophilus leucurus

| ||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

|

Sciuromorpha |

Rodents are members of the order Rodentia, which is the largest order of mammals. Rodents are most distinguished by their teeth — the word "rodent" comes from the Latin word "rodere", meaning "to gnaw."

There are about 1500 species of rodents (Nowak 1983, UCMP 2007), including mice, rats, squirrels, and beavers. They are found on all continents except Antarctica and in almost all land habitats from tropical forests to deserts to mountains and tundras. Rodents and bats are the only orders of placental mammals with species native to Australia.

Rabbits, hares, and pikas are not rodents, but members of another order, Lagomorpha.

Rodent characteristics

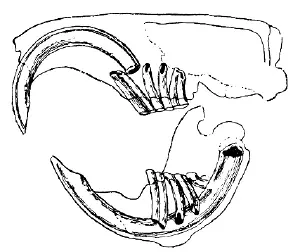

The incisor teeth of rodents are their most distinctive feature. An rodent's incisors grow continuously throughout its life and must be kept worn down by gnawing. The incisors of a pocket gopher can grow 20 inches in one year. The incisors have enamel on the outside and exposed dentine on the inside, so they self-sharpen during gnawing. Rodents lack canines and first premolars, which creates a space between their incisors and their grinding teeth.

Most rodents are small; the tiny African pygmy mouse (Mus minutoides) is one of the smallest rodents and is only 6 cm (2.5 inches) long and weighs 7 grams (.25 oz). The largest living rodent, the capybara (Hydrochoerus hydrochaeris) can weigh up to 45 kg (100 pounds) and the extinct Phoberomys pattersoni is believed to have weighed up to 700 kg (1500 lbs).

Most rodents mature quickly and soon have offspring. A female meadow mouse (Microyus pennsyvanicus) can have up to 17 litters of 4 to 13 young in a year. Many rodents have an average life span of only a year or less, although some larger rodents such as beavers and porcupines can live over 20 years. The oldest recorded rodent was a Sumatran crested porcupine (Hystrix brachyura) which lived 27 years and 3 months (Voelker 1986).

Rodents in nature

Most rodents eat plants, including seeds, fruit, grasses and leaves, and the bark of trees. Some rodents prey on insects and other small animals. The fish eating rats (Ichthyomys species) of South America and some others swim in streams to catch small fish. The naked mole rat (Heterocephalus glaber) spends its entire life underground. Flying squirrels live their lives in trees and glide, not truly fly, between trees to avoid spending time on the ground. Many rodents living in colder climates hibernate to conserve energy during the winter.

Some squirrels help maintain and spread forests by burying the seeds of trees. The seeds of the Brazil nut tree will not germinate unless they are first gnawed open and buried by an agouti (Dasyprocta species) (Attenborough 2002). Gophers, ground hogs, prairie dogs, and other burrowing rodents enrich the soil by mixing it and by burying vegetation. Beavers (Castor species), by their dam building, help control flooding and create pond and meadow habitats which benefit many other species.

Rodents are often the most abundant small animals in their habitats and are an important source of food for many other animals, including birds, reptiles, and other mammals. If their numbers were not kept in check by predators rodents would soon over run their environments. Norwegian lemmings (Lemmus lemmus), and some other rodents, undergo "population explosions" every few years. This is thought to help them expand their range into new areas.

Rodents and humans

From earliest times rodents have been eaten by humans. Although the flesh of all species is edible, rodents are not an important food source in the world today. Among the exceptions are the capybara and the guinea pig (Cavia porcellus) of South America and the bandicoot rat (Bandicota bengalensis) of Southeast Asia. The dormouse (Glis glis) was considered a delicacy in ancient Rome and is still eaten in parts of Europe today. In North America squirrels, groundhogs, muskrats, and porcupines are sometimes eaten.

The fur of some rodents is also an important product. The trapping of beavers for their fur played an important part in the history of North America. Some other rodents are also trapped for fur in the wild, while the chinchilla (Chinchilla laniger) of South America is raised for its fur.

The greatest impact of rodents on humans began when agriculture began and people started to live in settled homes. At that time some rodent species moved into human dwellings, especially to eat stored grain and food scraps and to benefit from warm living spaces and protection from predators. The house mouse (Mus musculus), which seems to be native from the Mediterranean area to China, and several species of rats (Rattus species), native to Southeast Asia, were the most successful and now live with humans all over the world.

Although the great majority of rodent species do no harm to humans, these commensal (which means "sharing the same table") species, especially the rats, do a tremendous amount of damage to crops and stored food. They also spread diseases, including the bubonic plague which has killed tens of millions of people through history and is still a danger today.

Rats also do a lot a damage to the natural environments where they have been introduced by humans. The black rat (Rattus rattus), also known as the ship rat, was carried around the world on sailing ships and has contributed to the extinction of many species of birds and other animals, especially on remote islands (ISSG 2007).

Many wild rodent species and subspecies are now endangered because of habitat loss and introduction of invasive species, including rats (IUCN 2007).

Some species of rodents are kept as pets. One of the most popular rodent pets is the golden hamster (Mesocricetus auratus). All of the world's pet golden hamsters are descendants of one family captured in Syria in 1930 (Voelker 1986). Other rodent pets include mice, rats, and guinea pigs.

Rodents also play an important role as subjects of scientific research. One reason for this is that with their short lives many generations can be studied in a few years. Research on mice, rats, and guinea pigs has contributed greatly to our understanding of biological processes and has helped to save millions of human lives.

Classification

The rodents are part of the clades: Glires (along with lagomorphs), Euarchontoglires (along with lagomorphs, primates, treeshrews, and colugos), and Boreoeutheria (along with most other placental mammals). The order Rodentia may be divided into suborders, infraorders, superfamilies]] and families.

Classification scheme:

ORDER RODENTIA (from Latin, rodere, to gnaw)

- Suborder Sciuromorpha

- Family Aplodontiidae: mountain beaver

- Family Sciuridae: squirrels, including chipmunks, woodchucks, and prairie dogs

- Family Gliridae (also Myoxidae, Muscardinidae): dormice

- Suborder Castorimorpha

- Superfamily Castoroidea

- Family Castoridae: beavers

- Superfamily Geomyoidea

- Family Heteromyidae: kangaroo rats and kangaroo mice

- Family Geomyidae: pocket gophers

- Superfamily Castoroidea

- Suborder Myomorpha

- Superfamily Dipodoidea

- Family Dipodidae: jerboas and jumping mice

- Superfamily Muroidea

- Family Platacanthomyidae: spiny dormice

- Family Spalacidae: mole rats, bamboo rats, and zokors

- Family Calomyscidae: mouse-like hamsters

- Family Nesomyidae: climbing mice, rock mice, white-tailed rat, Malagasy rats and mice

- Family Cricetidae: hamsters, New World rats and mice, voles

- Family Muridae: true mice and rats, gerbils, spiny mice, and the crested rat

- Superfamily Dipodoidea

- Suborder Anomaluromorpha

- Family Anomaluridae: scaly-tailed squirrels

- Family Pedetidae: springhares

- Suborder Hystricomorpha]

- Family incertae sedis Diatomyidae: Laotian rock rat

- Infraorder Ctenodactylomorphi

- Family Ctenodactylidae: gundis

- Infraorder Hystricognathi

- Family Hystricidae: Old World porcupines

- Family Erethizontidae: New World porcupines

- Family Thryonomyidae: cane rats

- Family Petromuridae: dassie rat

- Family Bathyergidae: African mole rats

- Parvorder Caviomorpha

- Family Octodontidae: octodonts

- Family Echimyidae: spiny rats

- Family Capromyidae: hutias

- Family †Heptaxodontidae: giant hutias

- Family Myocastoridae: nutria

- Family Dasyproctidae: agoutis

- Family Dinomyidae: pacaranas

- Family Caviidae: cavies, including guinea pigs

- Family Hydrochoeridae: Capybara

- Family Chinchillidae: chinchillas and viscachas

- Family Abrocomidae: chinchilla rats

- Family Ctenomyidae: tuco-tucos

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Attenborough, D. 2002. The Life of Mammals. Princeton, New Jersey : Princeton University Press

- IUCN Species Survival Commission (IUCN). 2007. .2007 ICUN Red List of Threatened Species. International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Invasive Species Specialist Group (ISSG). 2007. Global invasive species database: Rattus rattus. Invasive Species Specialist Group Website. Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Nowak, R. M., and J. L. Paradiso. 1983. Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801825253

- University of California Museum of Paleontology (UCMP). 2007. "Rodentia" Retrieved March 3, 2007.

- Voelker, W. 1986. The Natural History of Living Mammals. Medford, New Jersey: Plexus Publishing, Inc. ISBN 0937548081

| Mammals |

|---|

| Monotremata (platypus, echidnas) |

|

Marsupialia: | Paucituberculata (shrew opossums) | Didelphimorphia (opossums) | Microbiotheria | Notoryctemorphia (marsupial moles) | Dasyuromorphia (quolls and dunnarts) | Peramelemorphia (bilbies, bandicoots) | Diprotodontia (kangaroos and relatives) |

|

Placentalia: Cingulata (armadillos) | Pilosa (anteaters, sloths) | Afrosoricida (tenrecs, golden moles) | Macroscelidea (elephant shrews) | Tubulidentata (aardvark) | Hyracoidea (hyraxes) | Proboscidea (elephants) | Sirenia (dugongs, manatees) | Soricomorpha (shrews, moles) | Erinaceomorpha (hedgehogs and relatives) Chiroptera (bats) | Pholidota (pangolins)| Carnivora | Perissodactyla (odd-toed ungulates) | Artiodactyla (even-toed ungulates) | Cetacea (whales, dolphins) | Rodentia (rodents) | Lagomorpha (rabbits and relatives) | Scandentia (treeshrews) | Dermoptera (colugos) | Primates | |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.